Conjoined twins are successfully separated after being locked in embrace

After Phil and Alyson Irwin found out she was pregnant with their second child, they thought "a very big boy" was going to follow their first daughter, Kennedy. But in February 2019, at the 20-week checkup, they learned they were expecting identical twin girls — who were conjoined at the chest.

The odds were at least 1 in 50,000, and with a Google search that night, the parents from Petersburg, Michigan, quickly learned that most conjoined twins are either stillborn or die shortly after birth.

"I had the hardest time wrapping my head around the numbers," Phil Irwin, 32, told TODAY.

After getting the news, the Irwins were referred to specialists at the University of Michigan, who thought they might be able to help.

"It went from being very devastating to, 'Well, maybe there's a chance,' at least in my head," Phil said. "It felt like no hope to at least a glimmer of hope that things could go well."

Around when Alyson was 25 weeks pregnant, an echocardiogram revealed that separation of their twin daughters would be possible.

"They were able to tell that the hearts were very, very close, but they were separate," Alyson Irwin, 33, told TODAY. "That was the deciding factor for a lot of people. That they had separate hearts, it was a possibility."

Still, it was unclear if the girls would be able to breathe normally, if separated. The Irwins were initially told their daughters might "only be able to survive on a ventilator," Alyson recalled, but then, Dr. George Mychaliska, a fetal and pediatric surgeon at C.S. Mott Children's Hospital, said he thought he could help.

"It just felt like the biggest roller coaster," Alyson added. "(It was) like an emotional whiplash day. ... There was a huge possibility of stillbirth or not making it to full term, so for me it was hard to get too excited or too hopeful."

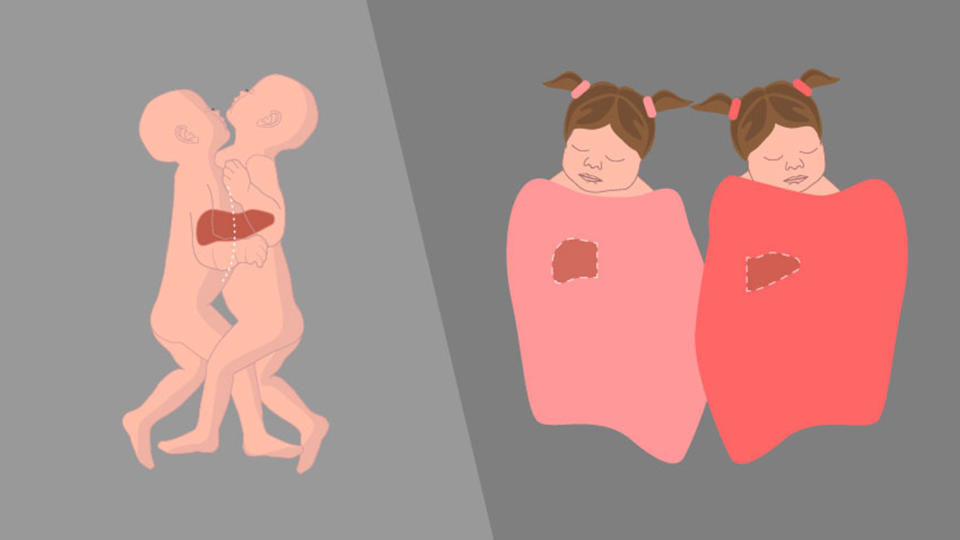

Sarabeth and Amelia Irwin were born via cesarean section in June 2019 with separate hearts and digestive tracts but connected livers. They spent the next 85 days in Mott's intensive care unit, and the separation surgery was scheduled for February 2020. But the girls got sick the week before, so it had to be canceled. Then the coronavirus outbreak hit.

"From the girls being born until February, I feel like we were mentally preparing ourselves for that day," Phil said. "Then when everything else happened, we went back home and we had a pretty good pandemic at home."

"We had a lot of really good family time together," he continued. "We got to watch the girls grow and get so strong and so healthy that it made me feel really, really good leading up to the second scheduling of their surgery."

For the medical team at Mott, the months leading up to the surgery on Aug. 5 were "a long journey," Mychaliska told TODAY. "Dozens of people from seemingly obscure areas of the health system (participated) in this project. ... We had to innovate in terms of all of the monitoring and data capture to have two patients in one room, which is obviously highly unusual."

Mychaliska added that the "biggest unknown" was whether they could reconstruct the girls' chest walls in a way that allowed them to breathe independently. But thanks to titanium plates covered with soft tissues and skin, the end result worked "beautifully," he said.

The successful separation surgery, which took 11 hours, is the first of its kind at Mott and, it's believed, in Michigan history, according to University of Michigan Medicine.

The twins stayed at the hospital for a month following surgery, and went home in early September. In that short time, the Irwins have gotten to watch their daughters develop as individuals. The parents always knew the twins' had distinct personalities, but watching Sarabeth "shine" has been the "biggest surprise," Phil said.

"Amelia is a little bit of a princess or a diva," he joked. "She wears all of her emotions right on her sleeve. There's no hiding how Amelia feels. ... Now that they're separate, it's so funny to see Sarabeth's quirky personality ... just physically, emotionally and mentally, how goofy that little girl really is."

Conjoined twins who survive separation surgeries often fall behind on developmental milestones, but Mychaliska said that they're catching up quickly and "look fantastic. ... It still seems a bit surreal that they're separated. It's overwhelming but in a very positive way."

The girls are already "so fast" with their crawling and scooting, Phil said. "It was like they'd been weight training for 15 months, carrying double the body weight."

According to Mychaliska, Sarabeth and Amelia's current prognosis is "very favorable for a normal life."

Or in their dad's words? "If you didn't know the girls before August, you'd have a hard time believing that they had been conjoined," he said.