Character and Plot Tropes in Japanese Otome Games

By Xiaolan You (2017)

Otome games, literally “maiden games”, are a popular Japanese genre of plot-based video games marketed towards women (Kapell). The protagonist, usually female, explores a romantic relationship with male love interests over a main storyline. Otome games are most commonly presented in visual novel or dating simulation format, and focus on visual storytelling and dialogue.

Although the genre originated in Japan in the mid 1990’s, an eruption of English translation and domestic production of games in the past decade allows English speakers around the world to access otome games. However, English speakers do not only encounter the barrier of translational delay—they must cross cultural differences as well. In this paper, I apply research methods of American romance novel scholars to analyze prevalent tropes in otome games. I seek to identify common character archetypes and plot narratives in otome games, which may assist American readers to easily immerse themselves into culturally Japanese games.

History of Otome Games

In Japanese, the term “shojo”, or “young woman”, is commonly used to refer to popular culture of fashion or entertainment that celebrates teen maturation (Kapell, p. 135-138). The nostalgic term “otome”, or “maiden”, is less commonly used. Otome culture “revive[s] conventional ideas of femininity and heterosexual narratives… [and] celebrate the positive energy of romance” (p. 136).

The 1994 release of “Angelique” by Koei Co. for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System marked both Japan’s first female-oriented game and first otome game (Kim). An all-female team produced Angelique in an effort to capture the steadily growing Japanese female gamer base. Angelique established both the genre’s success and its common conventions (Kim). First, the game featured a female protagonist and nine male love interests available for romantic perusal, which remains a common format today. Second, simple static game controls allow players to focus on visual elements and game plot without the distractions of elaborate strategy or first-person battles typical of action games. Third, otome game character and visual designs are closely influenced by those found in Japanese shoujo manga, or illustrated comics for young females.

Successor games such as Messiah’s “The Maiden of Albarea” in 1997 and E3 Staff’s “Graduation M” in 1998 further diversified the genre by adding in elements of fantasy, history, and adventure (Kim). Today otome games are so popular that many Japanese game retailers designate a shelf purely for “games targeted at women” (Beusman, 2016). Millions worldwide play games released by companies like Voltage Inc., Konami, and Idea Factory (“Voltage’s Visual Romance Apps”). Otome games produced for most gaming systems, including the Playstation, Nintendo DS, PSP, and mobile phones.

Recently, the American otome industry has seen explosive growth as an increasing number of games are localized. Otome company Voltage Inc. leads the genre’s entry into the American market (“Voltage’s Visual Romance Apps”). With 2015 sales totaling nearly $90 million across more than 50 million players globally, the industry giant produces popular mobile otome apps in both Japanese and English (Beusman, “Voltage’s Visual Romance Apps”). The company was founded in 1991 as a producer of mobile otome apps, and first began translating its Japanese games into English in 2011, marking the genre’s debut into American markets (“Corporate History”). Since then, Voltage has produced over 80 Japanese otome games and has translates 35 into English, with the latest debuting in March 2017 (Beusman). In addition, the company’s American subsidiary Voltage Entertainment USA has released 7 exclusive apps in English. A reader survey of popular English-language otome fan blog “Otome Otaku Girl” revealed that Voltage is the most preferred otome company by the American market.

Otome games for non-mobile gaming systems also continue to be localized to American markets with steady success; these include Hakuoki by Idea Factory on Nintendo 3DS, PS3, and PSP, and Code: Realize by Aksys Games on PS Vita (“Top 10 Otome”).

Study of Tropes

Tropes refer to commonly recurring themes and devices, and I narrow my study to the tropes in two areas: character archetypes and plot narratives. Limited scholarly research exists regarding tropes in otome games. Thus in this paper, I will first study how scholars analyze tropes in another form of popular entertainment, the American romance novel, and then apply their research methods in my own analysis of tropes in otome games.

Analyzing Plot Narratives

Why do authors use tropes, and why are readers drawn to them? In the words of authors Linda Barlow and Jayne Ann Krentz, romance writers construct their fictional universe—the plot, characters, and setting—with “familiar symbols, images, metaphors, paradoxes, and allusions to the great mythical traditions” that make romance plots both familiar and accessible (Rodale, p. 16-17). As readers and writers reencounter certain tropes, they mentally associate the tropes with “coded” responses—specific emotional and intellectual responses to certain words, phrases, or plot elements. Barlow and Krentz further note that “[t]he worldwide popularity of romance novels is a testimony to the way the familiar codes are universally recognized by women”—and demonstrates how the language of romance transcends linguistic and cultural borders (p. 20).

The universal nature of these tropes lies in their shared origin from history, myths, and legends. Krentz notes that “[a]t the core of each genre lie a group of ancient myths unique to that genre”—myths that transcend cultures (Rodale, p. 112-113). The archetypal knight in shining armor who rescues the damsel-in-distress from a fire-breathing dragon calls back to the legendary Greek hero Perseus’s rescue of Princess Andromeda from a sea serpent. A parallel legends in Japan is Susano-o’s slaying of eight-headed serpent Yamata-no-Orochi to save the young maiden Kushinada-hime (“The Kojiki”). Another popular archetype is known as Cinderella to American readers, or Chūjō-hime to Japanese. Players of otome games are also drawn to tropes that stem from these shared legends, and the familiar coded language of romance successfully transport American players into a universe fashioned by Japanese creators.

In my research for scholarly literature of plot tropes, I found that scholars regularly refer to plot tropes without citation—they are deemed common knowledge as they’re so often encountered. For example John Cawelt notes the following for romance novel tropes: “A favorite formulaic plot is that of the poor girl who falls in love with some rich or aristocratic man, which might be called the Cinderella formula. Or there is the Pamela formula, in which the heroine overcomes the threat of meaningless passion in order to establish a complete love relationship” (Cawelti, p. 41). The author provides no citations to scholarly analysis or even the original tale, because the tropes are so well known. Romance novelist Mindy Klasky features a broad array of these plot tropes on her website, which includes “arranged marriage”, “enemies to lover”, and “office romance”, all outlines with just a general description (Klasky).

Analyzing Character Archetypes

While the website TvTropes handles enormous compilations of thousands of tropes, romance novel tropes are usually not established by scholarly research, but rather as readers see repeating occurrences. Similar to plot tropes, limited professional literature exists on compiling character tropes in romance novel. Scholarly analysis tends to focus on one specific and often unusual trope for analysis, such Jonathan Allan’s examination of the virginal hero (Allan).

Allan’s paper identifies four common types of virginal heroes: the sickly virgin, the student virgin, the genius virgin, and the virgin as commodity. In his analysis, Allan first states an archetype and listing characteristic behavior or background. He follows with in-depth analysis of one or two heroes from a well-known author’s novel to establish the archetype’s credibility and behavior in text. Notably, Allan does not explain how he derived the four archetypes of virginal heroes, implying that such trends of behavior are so commonly seen that they are implicitly a “type”.

Thus I turned my attention away from academic analysis and instead to the opinions of romance authors and readers, who are intimately familiar with character tropes used in the genre. Romance author Tami Cowden published a piece on well-known blog “All About Romance” entitled “We Need a Hero: A Look at the Eight Hero Archetypes”. Cowden, along with fellow authors Caro LaFever and Sue Viders, identified the following eight master archetypes for heroes: the Chief, Bad Boy, Best Friend, Charmer, Lost Soul, Professor, Swashbuckler, and Warrior (Cowden).

Under each archetype, Cowden first lists the hero’s common personality traits and background. For example, she describes the Chief as “the quintessential alpha hero” who is “tough, decisive, goal-oriented. That means he is also a bit overbearing and inflexible… If he’s not already number one, it’s only a matter of time”. She then gives examples of the hero in both popular literature and specific romance novels. For instance, Captain Kirk from Star Trek, Brandon from The Flame and the Flower, and many heroes of the Harlequin Presents line are all Chiefs. The format of Allan’s scholarly analysis and Cowden’s informal analysis are remarkably similar; both identifying archetypes by familiarity with the literature, describe archetypal characteristics, and then provide specific examples from romance novels.

Case Study: Voltage Inc. Otome Games

Voltage’s mobile otome gameplay features the player acting as a female protagonist who is thrown into a situation with multiple male love interests. Usually 6 to 12 love interests are available for romantic relationships, typical of most otome games. A large portion of text is displayed through dialogue on the screen, and illustrated male characters and settings bring a unique visual component to the story. The player decides the protagonists’ name and in-game choices, such as “A: Chase after him” or “B: Let him go”. These choices influence the “happiness tier” of a route’s happily ever after. With these methods, the player can easily take the place of the heroine and can deeply experience the romanticism of the game.

The company’s games are targeted towards younger school-aged women, although the majority of players are actually older women in their late 20’s or 30’s (Dickson). Games focus on romantic interaction with no explicit sexual material; I describe the gestures as “heart fluttering” rather than “heart pounding”.

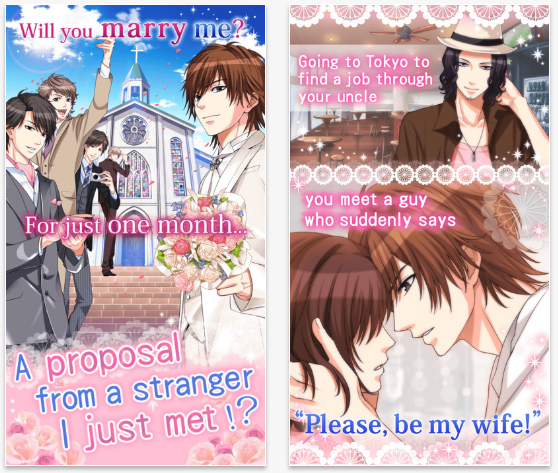

Otome Plot Tropes

Voltage otome games range over a variety of plot, settings, and style, but I observe that games can generally be grouped into four categories: luxury, slice of life, fantasy, and historical games. Luxury games are characterized by inter-class relationship, such as those with royalty or celebrities. The heroine almost always hails from a lower class, and her romantic relationship with the high-status male puts her into contact with wealth, fame, and the elite class. For example, in Kissed by the Baddest Bidder (KBTBB) the heroine stumbles upon Japan’s wealthiest mafia members and is chosen to serve one of the members, while Be My Princess (BMP) involves romance with a modern-day prince (“Voltage Lineup”). In Scandal in the Spotlight (SITS), a world-famous pop band hires the protagonist as a ghostwriter, and she pursues a relationship with one of the band members. By my calculations, Voltage has published 8 luxury plot games out of 35 total apps.

Slice of life games are Voltage’s most commonly published setting, numbering an astonishing 20 apps. Often set in the workplace or at school, slice of life games deal with domestic life and are easily relatable to players. Examples include Metro PD: Close to You (Metro PD), where the protagonist works as a rookie detective and falls in love with a co-worker while solving exciting cases. In Our Two Bedroom Story, romance blooms as the heroine shares a house with a coworker.

The last two plot categories are more rare, with only 3 and 4 published apps, respectively. Fantasy games often deals with myth or legends, such as Star Crossed Myth (SCM) where the heroine is the reincarnation of a goddess and helps a god absolve his sins. Historical apps are often set in Japanese Sengoku or Tokugawa period, with samurai (Sakura Amidst Chaos) or Shinsengumi warrior (Era of Samurai: Code of Love) based romance.

Aside from settings, the game title often describes which tropes may be used. My Forged Wedding (MFW) places the heroine in a variety of fake engagements. Others examples include Pirates in Love (pirates), My Sweet Bodyguard (guardian), A Knight’s Devotion (knight and lady), Butler Until Midnight (master and servant), and After School Affairs (teachers). The majority of plot settings, genres, and tropes are familiar to readers outside of Japan, and may be helpful to ease an American reader’s emersion into the game.

Otome Character Archetypes

Each game begins as the player is introduced to multiple male love interests, and then choses to pursue a relationship with one love interest. Voltage games usually offer six initial male interests with radically different personalities, background, and conflicts—minor characters are often also added in later updates. The variety of male interest “types” satisfies players’ broad range of taste. In my analysis of otome male leads, I will adopt a similar format to Allan and Cowden’s analysis by first identifying archetypal characteristics and then providing specific examples. By drawing from my personal observations, I identify six main character archetypes prevalent in Voltage otome games.

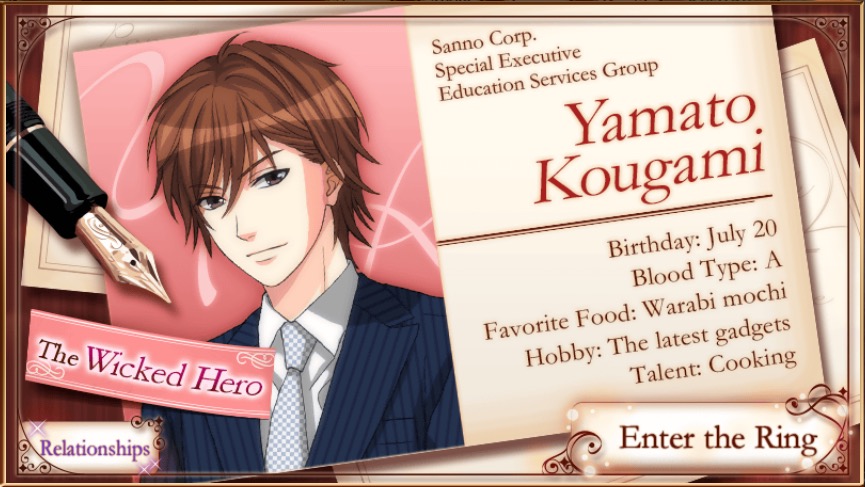

First is the Commander. He’s the main vocalist of the band, the ringleader of the team, the CEO of the company. The Commander is characterized by his aggression, dominance, and always getting what he wants… until he meets the heroine. He loves teasing the heroine but also protects her, especially from the glances of other men. He’s the otome equivalent of Cowden’s Chief archetype, and appears in romance novels as the “duke” or “billionaire”. The Commanders are mostly visibly featured in promotional media and can be considered the game’s flagship character. Examples include Yamato from MFW and Eisuke from KBTBB.

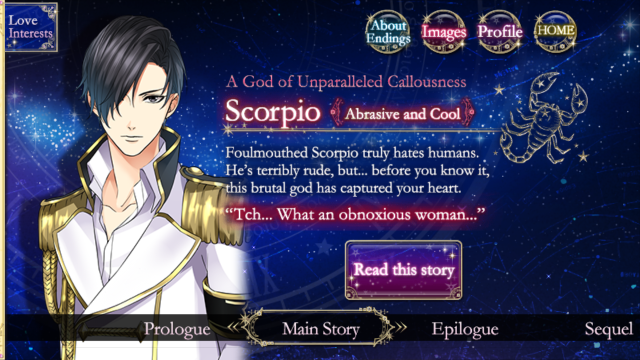

Second, the Sophisticated Cynic is snarky, intelligent, and mysterious. He has sworn off emotional entanglement because of tragedy in his past and actively pushes women away. However the protagonist tears down his ice-cold barriers to reveal his true passionate nature. Sophisticated Cynics are similar to the “dark lords” from paranormal novels. Otome examples include Scorpio from SCM and Joshua from BMP.

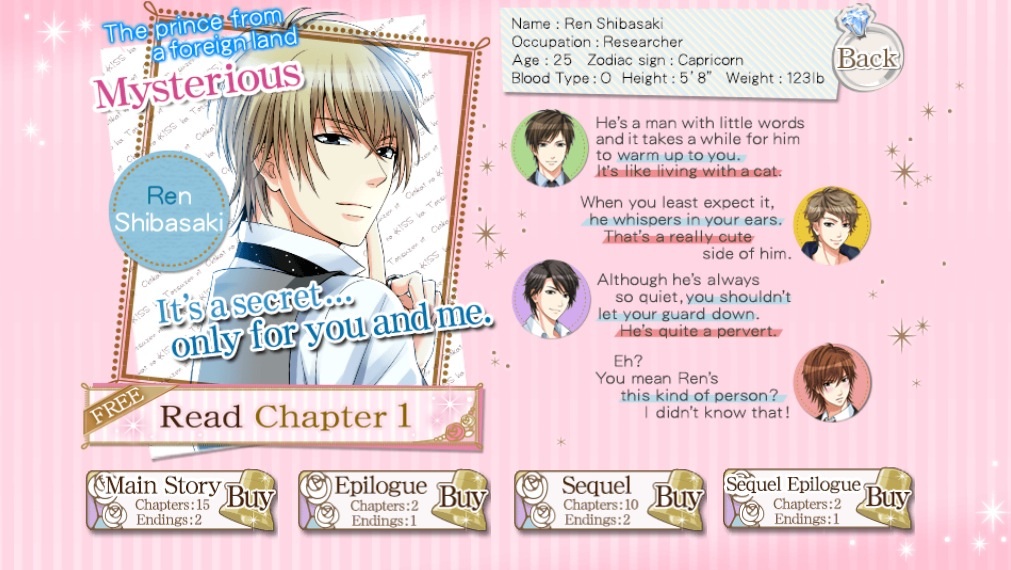

Third, the Quiet Introvert is polite, intelligent, and hard to read. However, the protagonist draws him out of his shell, and only she sees his buried warmhearted nature. If the Commander is not promoted as the game’s titular character, then the role usually belongs to the quiet introvert. He is frequently blonde, as is the case for Ren from MFW and Noel from Seduced in the Sleepless City.

Fourth, we have the arrogant, fun-loving playboy—the Flirt. He is fascinated by the heroine’s refreshing honesty and innocence so different from all the previous women he has encountered, and reforms his scandalous lifestyle for her. This trope echoes the “reformed rakes” of historical romance novels. Saeki from MFW and Kyoga from Enchanted in the Moonlight are both notorious flirts who also later reform themselves.

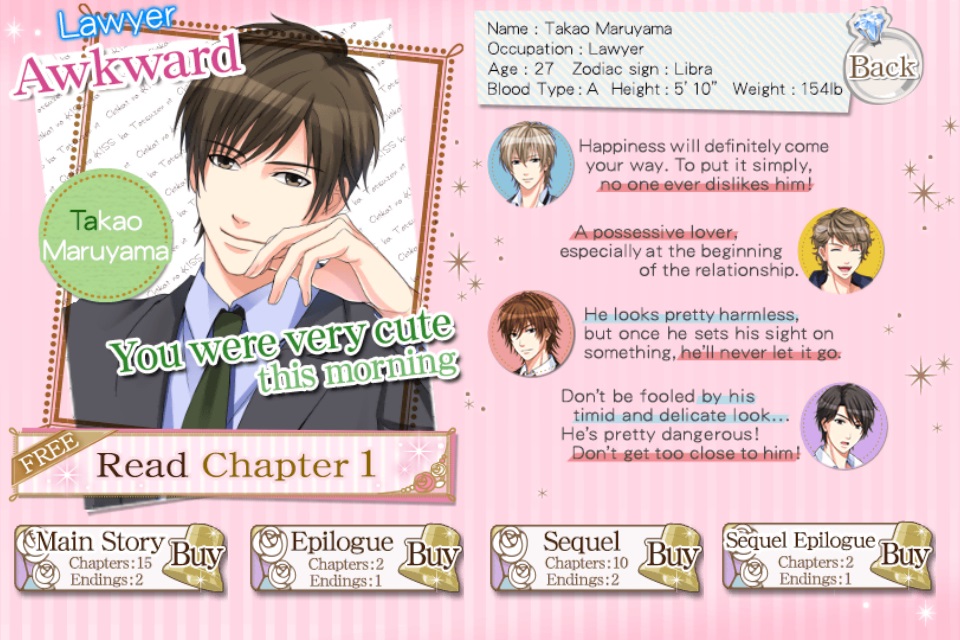

Fifth, the Mature Nice Guy is down-to-earth, reliable, and has a perfectly put-together life—except in the romance department. He’s never felt this way about a woman until he meets the protagonist. While other love interests are mid to late 20’s, he can sometimes older (30’s) in which case he may be the only love interest to have facial hair. Many contemporary romances feature similar nice guy or “beta” heroes. In MFW, Takao is a younger Mature Nice Guy while Kunihiko is older.

Sixth, the Younger Guy is earnest, enthusiastic, and always striving to do better. Nonetheless, he’s tried of being underestimated and wants others to acknowledge his maturity. The heroine is his first love, and he tries hard to be the man of her dreams. Such heroes also appear in romance novels featuring a younger suitor and older heroine. Examples include Yuta from MFW and Glenn from BMP.

While the above character archetypes are general templates, Voltage’s male heroes are unique and exhibit varied traits and it’s often difficult to categorize them. For example, Soryu from KBTBB is the leader of the Hong Kong mafia and operates from the shadows; he exhibits characteristics of the Commander, Sophisticated Cynic, and Quiet Introvert. The Flirt and Commander also often overlap. Notably, all archetypes will exhibit Commander-like behavior at the romantic climax—even the quiet, introverted hero will boldly take hold of the heroine and sweep her away passionately. However, the usual six male love interests introduced in Voltage games are often distributed among the six character archetypes above, while later minor characters fill in additional variations. The varied and numerous personalities fulfill players’ desire for a specific “type” and generated broader appeal.

In addition, these character archetypes are generally familiar to international audiences even outside of Japan. For example, the Commander in otome and the Chief in romance are both “quintessential alpha hero[es]” (Cowden). The alpha hero is a universal archetype characterized by his strength, aggression, and a penchant for dominance. He is “an avatar for the romance community”, and commonly appears in novels as the billionaire CEO, royal prince, or famous athlete (Klasky, Bibbs, Berko & Panguluri). Traditional alpha heroes are often Byronic heroes, who are noted as the typical “wounded, brooding, unapproachable hypermasculine ‘alpha male’” (Bibbs, Berko & Panguluri). Contemporary portrayals have shifted to alpha heroes with some beta qualities such as “strong moral integrity, a hidden tenderness or ability to be lethal while consistently choosing not to be”.

The heroes of otome games are more closely related to modern alphas than traditional alphas—the Commander may be arrogant and rude but certainly not detestable, and the Flirt may chat up other women but he’s never shown to venture further. This difference may be because Voltage is targeting a younger audience with their games. In addition, the Japanese player base judge male love interests by different models of masculinity (Dickson). For example, heroes tend to be more androgynous in appearance and resemble slim anime characters more than the rugged, masculine Western alpha male ideal. Aside from physical distinctions, Voltage heroes also act more androgynous; it’s not uncommon to see them acting domestic, especially in slice of life games. For example, MFW’s Yamato is an expert cook who often gets up early to make breakfast for him and the heroine. Rather than appearing emasculated, heroes with domestic skills are still considered masculine in Japan as it suggests the man is both responsible and dependable.

Conclusion

The otome game genre has proven to be massively popular in Japan, and is now extending worldwide (“Voltage’s Visual Romance Apps”). As limited scholarly literature exists on otome games, I applied research methods used by romance novel scholars to otome—specifically to identify common plot and character tropes. Both professional and informal analysis followed a similar pattern; they identified the tropes from common knowledge of the literature, described its defining characteristics, which were supported with textual examples.

I used the same format to characterize common plot narratives and character archetypes in otome games. Using a case study of games by Voltage Inc., I categorized otome games into luxury, slice of life, fantasy, and historical settings, and described the characterization and common tropes of each. In addition, I identified common tropes in otome games such as those based on plot (e.g. arranged marriages) or setting (e.g. office romance). While I did not use textual examples due to space restriction, I named specific apps game plotlines as examples for each. Notably, many tropes and settings are familiar to readers even outside of Japan, perhaps because many tropes share their roots in similar myths. The use of these plot tropes allow non-Japanese readers to more easily immerse into otome games and bridge cultural barriers.

I also identified six common character archetypes among Voltage heroes: the Commander, Sophisticated Cynic, Quiet Introvert, Flirt, Mature Nice Guy, and Younger Guy. Again, I identified common characteristic and specific character examples of each archetype. Many archetypes are included in Voltage games to generate broad appeal, and practically all archetypes are familiar to American players. However, they exemplify more archetypes found in contemporary American romances, such as the modern alpha and beta heroes, then those of traditional romance novels. Otome character archetypes are also culturally influenced as they were designed with Japanese models of masculinity in mind and created for games targeting younger audiences.

While English otome games are increasingly common, the American otome player base is not yet established and thus these observations may change in years to come as companies adjust to the American market’s tastes. Already Voltage Inc. has established an American subsidiary company, which published original English otome games (“Voltage’s Visual Romance Apps”). While these games haven’t yet become popular, even among Voltage fans, their focus on Western comic-like art style, Western settings like New York City, and powerful heroines may sway American fans’ preferences (Dickson). However, as one intrigued scholar noted, much of otome games’ appeal lies in its inherent “Japaneseness”—including the exotic setting, foreign culture, unique visuals, and heart-fluttering romantic action (Kapell). Otome games bring a refreshing take on romance and allow players to re-experience their shared precious memories: the innocent love of their maiden days.

Sources

Allan, Jonathan A. “Theorising male virginity in popular romance novels.” Journal of Popular Romance Studies 2, no. 1 (2011).

Beusman, Callie. “My Sensual Journey into Japan’s $90 Million Fake Anime Boyfriend Market.” Vice. N.p., 18 Mar. 2016. Web. 03 May 2017.

Bibbs, Courtney, Katherine Berko, and Sai Panguluri. “Alpha Heroes.” Unsuitable. Duke University, 2016. Web. 03 May 2017. <https://sites.duke.edu/unsuitable/alpha-heroes-2/>.

Cawelti, John G. Adventure, mystery, and romance: Formula stories as art and popular culture. University of Chicago Press, 2014.

“Corporate History” Voltage Inc. (n.d.). <http://www.voltage.co.jp/en/corporate/history.html>

Cowden, Tami. “We Need a Hero: A Look at the Eight Hero Archetypes.” All About Romance. N.p., 14 May 1999. Web. 03 May 2017.

Dickson, EJ. “Can Japanese dating simulators tap into the Western market?” The Daily Dot, 2014. <https://www.dailydot.com/debug/voltage-japanese-romance-simulators/>.

Kapell, Matthew. Playing with the past: digital games and the simulation of history. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013.

Kim, Hyeshin. “Women’s Games in Japan: Gendered Identity and Narrative Construction.” Theory, Culture & Society 26, no. 2-3 (2009): 165-88. doi:10.1177/0263276409103132.

Klasky, Mindy. “Romance Tropes.” <http://www.mindyklasky.com/index.php/for-writers/romance-tropes/>.

“The Kojiki: Similarities to Other Mythology.” Japanese Mythology. <http://www.japanesemythology.jp/kojiki/4.html>.

“Top 10 otome games best recommendations.” Honeyfeed. (2015) <http://blog.honeyfeed.fm/top-10-otome-games-best-recommendations/>

Rodale, Maya. Dangerous books for girls: the bad reputation of romance novels explained. (2015). NY, NY.

“Voltage Lineup” Voltage Inc. (n.d.) < http://koi-game.voltage.co.jp/en/lineup/novel.html>

“Voltage’s Visual Romance Apps series is ranked #1 in 57 countries. And now it brings you its 35th app! “Irresistible Mistakes” Voltage Inc. (2017). <https://www.voltage.co.jp/en/p-release/170327.html>.