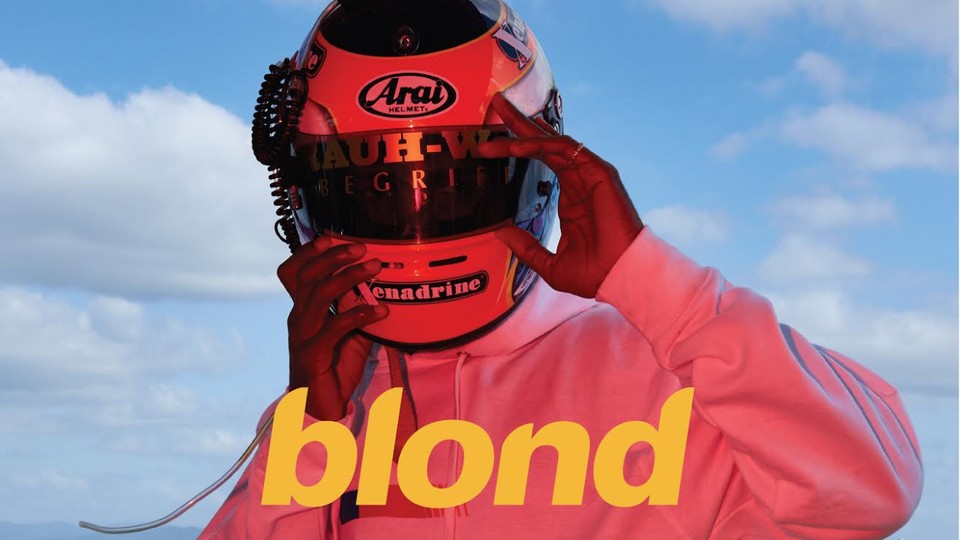

Frank Ocean's Blond(e) Is a Monument to Memory

Intensely emotional and uncompromising, the singer’s long-awaited new album meditates on the passage of time.

Frank Ocean is still thinking about forever. One of his two new albums is called Endless, even though its songs all seem to end too soon. The more significant release, called either Blonde or Blond depending on where you acquire it, repeatedly laments nights, season, and years that can never be retrieved. The first time his unadorned vocals appear on that album, Ocean sings, “We'll let you guys prophesy / We gon' see the future first.” The line comes across as a challenge to get on his level and unhitch from the present—a necessary step before accessing the deep pleasures of his uncompromising new music.

Ocean’s obsession with time has been well-documented by now. His 2011 debut had the self-explanatory title Nostalgia, Ultra and his 2012 breakout, Channel Orange, was inspired by a teenage summer that, he said, seemed “orange.” He’s like the memory machine in Pixar’s Inside Out, processing the past into gemlike objects that can be sorted by visual cue and emotional essence. The blonds and blondes of Blond(e) are, on one level of interpretation, ex-boyfriends and ex-girlfriends. He references car models—Acuras, Ferraris, X6s—as shorthand for life phases. And on the luminous new track “Ivy,” he describes a callous breakup but keeps saying that when he thinks about the relationship, “the feeling still deep down is good.” Good: one simple word explains and colors all the complexity he’s sung about elsewhere in the song.

Popular music usually has a clear and agreed-upon relationship to time, allowing you to live for three and a half minutes not by the ticktock of the clock but by the tap of your toe and your awareness of the number of choruses that have passed. Ocean previously made brilliant use of these conventions on his way to next-big-thing status in pop and R&B, but he has returned after a four-year silence with a radically different way of working. Save for one glorious pop waltz, “Pink + White,” the songs on Blond(e) mostly operate by the twisty logic of how a narrative might actually unfold in the mind, rather than on the radio. It’d be art nonsense if it didn’t pack so much power in so many unexpected places.

Ocean is still partly an R&B artist, but he increasingly submerges the “R” of rhythm and blues as long stretches of his music drift by with nary a drum hit or 808 clap. “Ivy” quavers on a fine knitting of guitar lines; “Solo” just has an organ; for a few moments on “Skyline To” it sounds like there’s a drum performance happening a room or two away from the vocal booth, providing more texture than timekeeping. It makes sense: Dance music is about the now, and these songs aren’t. Ocean sings about relationships defined by drugs and sex and car rides; occasional signifiers making clear we’re in the realm of memory, like when he adds the aside “16, what was I supposed to know” as the wide-eyed and wrenching “White Ferrari” unfolds.

The payoff of these songs often comes in musical shifts, when melodies turn plaintive and direct as Ocean pivots from describing small momentary details to longterm emotional effect. On “Solo,” what seemed like a irreverent tale of dropping acid and hooking up becomes total cry-bait as Ocean arches his voice upward and sings about hell, heaven, and the constellations. The fantastic “Self Control” begins as a high-pitched novelty track, turns into an acoustic-strummed sexual come on, and then effervesces with pained cries for companionship. As Ocean repeats his closing refrain on that song, it feels as though there’s an overhead camera pulling out from the scene he has described, the scope widening to encompass a planet’s worth of loneliness. The astonishing late-album run of “White Ferrari,” “Seigfried,” and “Godspeed” basically stays in that devastating mode the entire time—keep tissues nearby.

It’s not all so super-heavy, though. There’s a certified jam in “Nights,” built off of a riff where each chord seems to come from guitars of different tone—one twangy, one clean, one gauzy—creating the sensation of something coming in and out of focus. Strange sonic details throughout the album are like doodles in the margins, reminding of the very singular human brain at work. And the opener “Nikes” foregrounds a pitch-shifted voice (chipmunk-high on the record but Jabba-the-Hutt-low for the music-video version) in hip-hop toast mode, bragging about sex, lusting after sneakers, and mourning A$AP Yams, Pimp C, and Trayvon Martin. For a ramble, it’s pretty catchy, and it might represent Ocean’s affection for the culture that has so excitedly received him—but also his wariness about its, or any culture’s, materialist mainstream.

The other great hip-hop moment comes when Andre 3000 blazes through “Solo (Reprise),” a flood of syllables that first comes across as pure vivid boasting but becomes surprisingly gutting with later listens. Melancholy piano plays as Andre reaches the culmination of his verse:

After 20 years in

I'm so naive I was under the impression that everyone wrote they own verses

It's comin' back different and yea that shit hurts me

I'm hummin' and whistlin' to those not deserving

I've stumbled and lived every word, was I working just way too hard?

This is a clear diss to Drake, alleged to use ghostwritten songs. But it’s such a perfect moment for a Frank Ocean album, too: A singular artist noting, with regret, both the passage of time and his disconnection from the popular practice of his artform. Andre’s question of whether he has been trying too hard is already answered, both for him and Ocean—the end results have obviously been worth the effort.

Ocean delivers plenty of his own defiant lines throughout the album, talking about working on his own timetable and refusing expectations placed upon him by the masses—whether expectations as a man, a millennial, or a musician. Gay love is spoken about frankly, Facebook gets sneered at, and the hopes of anyone looking for another “Thinking Bout You” singalong are dashed time and again. If his interminable live-streamed construction project didn’t make it clear enough, Blond(e)’s music underscores that Frank Ocean just doesn’t think about time in the same way that the Internet masses who demanded he hurry up with this album do. What are four years next to forever?