Caesar rises from the Rhone - Minerva

Caesar rises from the Rhone - Minerva

Caesar rises from the Rhone - Minerva

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

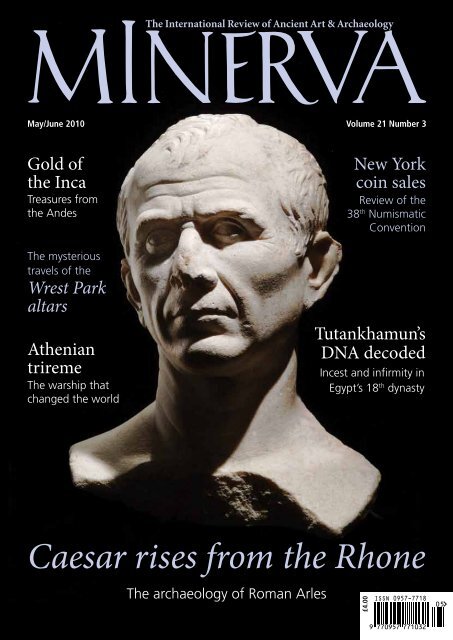

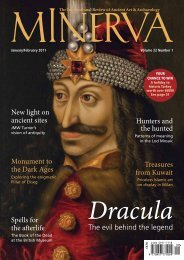

May/June 2010 Volume 21 Number 3<br />

Gold of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Inca<br />

Treasures <strong>from</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Andes<br />

The mysterious<br />

travels of <strong>the</strong><br />

Wrest Park<br />

altars<br />

A<strong>the</strong>nian<br />

trireme<br />

The warship that<br />

changed <strong>the</strong> world<br />

<strong>Caesar</strong> <strong>rises</strong> <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rhone</strong><br />

The archaeology of Roman Arles<br />

New York<br />

coin sales<br />

Review of <strong>the</strong><br />

38 th Numismatic<br />

Convention<br />

Tutankhamun’s<br />

DNA decoded<br />

Incest and infirmity in<br />

Egypt’s 18 th dynasty<br />

£4.00<br />

ISSN 0957-7718<br />

9 770957 771032<br />

05

May/June 2010 Volume 21 Number 3<br />

Gold of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Inca<br />

Treasures <strong>from</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Andes<br />

The mysterious<br />

travels of <strong>the</strong><br />

Wrest Park<br />

altars<br />

A<strong>the</strong>nian<br />

trireme<br />

The warship that<br />

changed <strong>the</strong> world<br />

<strong>Caesar</strong> <strong>rises</strong> <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rhone</strong><br />

The archaeology of Roman Arles<br />

Review of <strong>the</strong><br />

38th New York<br />

coin sales<br />

Numismatic<br />

Convention<br />

Tutankhamun’s<br />

DNA decoded<br />

Incest and infirmity in<br />

Egypt’s 18th dynasty<br />

On <strong>the</strong> cover: Marble head,<br />

possibly of Julius <strong>Caesar</strong>, c. 46<br />

BC. H. 39.5cm. Photo: Musée<br />

départemental Arles antique ©<br />

Maby J.-L_L.Roux.<br />

Annual subscription<br />

(6 issues)<br />

UK £21; Europe £23<br />

Rest of world:<br />

Air £33/US$66; Surface £25/<br />

US$50<br />

For full information see<br />

www.minervamagazine.com.<br />

Published bi-monthly.<br />

Send subscriptions to our<br />

London office, below.<br />

Advertisement Sales<br />

<strong>Minerva</strong>, 20 Orange Street<br />

London, WC2H 7EF<br />

Tel: (020) 7389 0808<br />

Fax: (020) 7839 6993<br />

Email: editorial@minerva<br />

magazine.com<br />

Trade Distribution<br />

United Kingdom:<br />

Diamond Magazine<br />

Distribution Ltd<br />

Tel. (01797) 225229<br />

Fax. (01797) 225657<br />

US & Canada:<br />

Disticor, Toronto<br />

Egypt & <strong>the</strong> Near East:<br />

American University in<br />

Cairo Press,<br />

Cairo, Egypt<br />

Printed in England by<br />

Broglia Press.<br />

All rights reserved; no part of this<br />

publication may be reproduced, stored<br />

in a retrieval system, or transmitted in<br />

any form or by any means, electronic,<br />

mechanical, photo copying, recording,<br />

or o<strong>the</strong>rwise without ei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> prior<br />

written permission of <strong>the</strong> Publisher/or<br />

a licence permitting restricted copying<br />

issued by <strong>the</strong> Copyright Licensing<br />

Agency Ltd, 33-34 Alfred Place,<br />

London, WC1E 7DP<br />

ISSN 0957 7718<br />

© 2010 Clear Media Ltd.<br />

<strong>Minerva</strong> (issn no 0957 7718) is<br />

published six times per annum by<br />

Clear Media Ltd on behalf of <strong>the</strong><br />

Mougins Museum of Classical Art<br />

and distributed in <strong>the</strong> USA by SPP<br />

75 Aberdeen Road Emigsville PA<br />

17318-0437. Periodical postage<br />

paid at Emigsville PA. Postmaster<br />

send address changes to <strong>Minerva</strong>,<br />

c/o SPP, PO Box 437, Emigsville PA<br />

17318-0437.<br />

The publisher of <strong>Minerva</strong> is not<br />

necessarily in agreement with <strong>the</strong><br />

opinions expressed in articles <strong>the</strong>rein.<br />

Advertisements and <strong>the</strong> objects<br />

featured in <strong>the</strong>m are checked and<br />

monitored as far as possible but are<br />

not <strong>the</strong> responsibility of <strong>the</strong> publisher.<br />

<strong>Minerva</strong> May/June 2010<br />

Features<br />

08 Tutankhamun’s DNA<br />

Recently published results of a two-year research programme<br />

contain surprising revelations about New Kingdom royalty.<br />

James Beresford<br />

12 Beauty or truth?<br />

A new book examines <strong>the</strong> Classical Greek ideal of <strong>the</strong> human form.<br />

Murray Eiland<br />

16 Ship of <strong>the</strong> people<br />

The democratic legacy created by <strong>the</strong> trireme, <strong>the</strong> warship which<br />

propelled Classical A<strong>the</strong>ns to naval supremacy. James Beresford<br />

20 From <strong>the</strong> central Aegean to rural England<br />

The strange and forgotten history of five Graeco-Roman altars<br />

brought <strong>from</strong> Delos to Bedfordshire. David Noy<br />

24 Picturing <strong>the</strong> past<br />

A look at <strong>the</strong> long and mutually beneficial relationship between<br />

photography and archaeology in investigations of Egypt’s history.<br />

Maria Golia<br />

28 River of memory<br />

A major exhibition in Arles features archaeological treasures<br />

recovered <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> swirling waters of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rhone</strong>. Elena Taraskina<br />

32 Out of <strong>the</strong> blue<br />

Aerial archaeological research offers a new and enlightening<br />

perspective on ancient Jordan. Robert Bewley and David Kennedy<br />

36 The fiery pool<br />

A new exhibition casts light on <strong>the</strong> role of <strong>the</strong> sea in <strong>the</strong> Maya world<br />

view. Sophie Mackenzie<br />

40 Civilisation of gold<br />

An exhibition in Brescia examines <strong>the</strong> origins of <strong>the</strong> Inca Empire.<br />

Dalu Jones<br />

44 High stakes<br />

The impact of <strong>the</strong> Aswan High Dam on Egyptian archaeology.<br />

Georgina Read<br />

48 Our man in Rome<br />

An interview with Prof Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, Master of Sidney<br />

Sussex College, Cambridge, and formerly Director of <strong>the</strong> British<br />

School at Rome. James Beresford<br />

52 Numismatic sales<br />

A review of some of <strong>the</strong> notable coins sold at <strong>the</strong> 38 th New York<br />

International Numismatic Annual Convention. David Miller<br />

Regulars<br />

02 From <strong>the</strong> Editor 03 News<br />

58 Book Reviews 60 Calendar<br />

contents<br />

volume21 number3<br />

08<br />

32<br />

40<br />

44<br />

36<br />

1

<strong>from</strong><strong>the</strong>editor<br />

Archaeology and<br />

<strong>the</strong> technology<br />

of humanity<br />

Since <strong>the</strong> dawn of time, humanity has undergone a series of<br />

technological advances that express <strong>the</strong>mselves in <strong>the</strong> archaeological<br />

record. Today, technology allows archaeological enquiry to an<br />

unprecedented extent.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> last editorial I highlighted<br />

<strong>the</strong> interplay between humans<br />

and <strong>the</strong> role of <strong>the</strong> environment<br />

as a common thread running<br />

through <strong>the</strong> splendid range of<br />

articles in <strong>Minerva</strong>. Curiously,<br />

in this issue many of <strong>the</strong> topics covered have<br />

a common <strong>the</strong>me of a different nature – a<br />

component of equal importance that has<br />

enabled our species to progress since <strong>the</strong><br />

production of <strong>the</strong> first stone tools 2.5 million<br />

years ago: technology.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> Western world we look to ancient<br />

Greece as <strong>the</strong> cradle of our modern civilisation,<br />

which gave birth to a sophisticated architecture,<br />

arts, democratic government, law, literature<br />

and learning, not least philosophy. Plato<br />

derided <strong>the</strong> rowers who manned <strong>the</strong> trireme,<br />

<strong>the</strong> technological advance that shaped <strong>the</strong><br />

A<strong>the</strong>nian state, while his mentor Socrates<br />

observed <strong>the</strong> perfect human form in <strong>the</strong> athlete<br />

Charmides – a physique that came to epitomise<br />

<strong>the</strong> ideal in Greek sculpture.<br />

Contributors<br />

An independent artistic current flourished<br />

in <strong>the</strong> ancient American civilisations. The<br />

beautifully crafted ceramics of <strong>the</strong> Maya and<br />

<strong>the</strong> opulent gold of <strong>the</strong> Inca were made possible<br />

by technological advances in craftsmanship.<br />

The relationship between Egyptology and<br />

technology has ushered in fur<strong>the</strong>r innovations<br />

in scholarship and technical advances. This is<br />

especially true in <strong>the</strong> study of Egyptian sites,<br />

which was greatly assisted by <strong>the</strong> development<br />

of photography, and <strong>the</strong> extraordinary DNA<br />

analysis of mummified remains, which has <strong>the</strong><br />

potential to offer information about may facets<br />

of Pharaonic life, not least genealogy.<br />

Archaeological survey, too, has benefited<br />

<strong>from</strong> recent technological progress, with <strong>the</strong><br />

enlightening aerial surveys of Jordan a prime<br />

example. If anatomically modern humans<br />

reached <strong>the</strong>ir maturity with <strong>the</strong> technological<br />

revolution of <strong>the</strong> Upper Palaeolithic, this very<br />

dynamic has paved <strong>the</strong> way to a world that will<br />

continue to change as this interplay progresses.<br />

Dr Mark Merrony<br />

Editor-in-Chief<br />

Dr Mark Merrony<br />

Editor<br />

Dr James Beresford<br />

Publisher<br />

Myles Poulton<br />

Managing Editor<br />

Sophie Mackenzie<br />

Art Director<br />

Nick Riggall<br />

Designer<br />

Lyndon Williams<br />

Editorial Associate<br />

Georgina Read<br />

Editorial Advisory Board<br />

Peter Clayton, FSA,<br />

London<br />

Prof Claudine Dauphin,<br />

Nice<br />

Dr Howard Williams,<br />

Chester<br />

Dr Murray Eiland,<br />

Frankfurt<br />

Massimiliano Tursi,<br />

London<br />

Prof Roger Wilson,<br />

Vancouver<br />

Correspondents<br />

David Breslin, Dublin<br />

Dr R.B. Halbertsma, Leiden<br />

Florian Fuhrman, Lisbon<br />

Dalu Jones, Italy<br />

Dr Lina Christopoulou, A<strong>the</strong>ns<br />

Dr Filippo Salviati, Rome<br />

Rosalind Smith, Cairo<br />

<strong>Minerva</strong> was founded in 1990 by<br />

Jerome M. Eisenberg PhD<br />

Published in England by<br />

Clear Media Ltd on behalf of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Mougins Museum of Classical Art.<br />

Clear Media is a<br />

Media Circus Group company<br />

www.clear.cc<br />

www.mediacircusgroup.com<br />

20 Orange Street<br />

London WC2H 7EF<br />

Tel: 020 7389 0808<br />

Fax: 020 7839 6993<br />

Email: editorial@minervamagazine.com<br />

Dr Murray Eiland Dr David Noy Maria Golia<br />

Elena Taraskina<br />

is an archaeologist<br />

based in Germany. His<br />

main interests are near<br />

Eastern archaeology and<br />

archaeological science,<br />

particularly ceramic<br />

materials. He has a wide<br />

interest in ancient art and<br />

travels extensively.<br />

Beauty or truth p.12<br />

is <strong>the</strong> author of Foreigners<br />

at Rome (2000), five<br />

volumes of Jewish<br />

inscriptions, and papers on<br />

roman social history and<br />

inscriptions. He teaches at<br />

<strong>the</strong> university of Wales,<br />

Lampeter and <strong>the</strong> open<br />

university.<br />

Wrest Park altars p.20<br />

is <strong>the</strong> author of Cairo,<br />

City of Sand (2004) and<br />

writes about cultural,<br />

social, political and<br />

economic aspects of<br />

Egypt. Her article draws<br />

on research used in her<br />

book Photography and<br />

Egypt (2009).<br />

Picturing <strong>the</strong> past p.24<br />

has lived and worked<br />

in Arabia, britain and<br />

her native russia. she is<br />

currently based at Aston<br />

College, birmingham<br />

where she has an interest<br />

in how <strong>the</strong> heritage sector<br />

operates within <strong>the</strong> wider<br />

economy.<br />

River of memory p.28<br />

2 <strong>Minerva</strong> May/June 2010

in<strong>the</strong>news<br />

recent stories <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> world of ancient art and archaeology<br />

The coast of Crete near Plakias, where <strong>the</strong> tools were found. Photo courtesy of Silvain de Munck.<br />

Ancient mariners on Crete?<br />

Researchers on Crete have uncovered<br />

evidence suggesting that early humans,<br />

or even earlier hominids, have had a<br />

much longer history of seafaring than was<br />

previously believed. Over <strong>the</strong> past two years,<br />

archaeologists working on <strong>the</strong> island have<br />

found stone tools which are considered<br />

strong evidence of <strong>the</strong> earliest known<br />

voyaging in <strong>the</strong> Mediterranean.<br />

Artefact discoveries have provided<br />

evidence that humans reached Cyprus,<br />

many o<strong>the</strong>r Greek islands and possibly<br />

Sardinia, no earlier than 10,000 to 12,000<br />

years ago. However, Crete has been an island<br />

for more than �ve million years, so <strong>the</strong><br />

anatomically modern humans – or possibly<br />

earlier hominids such as Homo erectus or<br />

Homo heidelbergensis – who le� <strong>the</strong>se stone<br />

tools, which archaeologists believe to be at<br />

least 130,000 years old, must have arrived<br />

<strong>the</strong>re by boat. � is pushes back <strong>the</strong> history<br />

of Mediterranean seafaring by more than<br />

100,000 years.<br />

Acheulean tools typically associated with<br />

Homo Erectus.<br />

<strong>Minerva</strong> May/June 2010<br />

More than 2000 stone artefacts, including<br />

hand axes, were collected on <strong>the</strong> southwestern<br />

shore of Crete, near <strong>the</strong> town of<br />

Plakias, by a team led by � omas F. Strasser,<br />

Associate Professor of Art History at<br />

Providence College in Rhode Island, toge<strong>the</strong>r<br />

with Eleni Panagopoulou of <strong>the</strong> Greek<br />

Ministry of Culture.<br />

� e tools resemble artefacts <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> stone<br />

technology known as Acheulean, which<br />

originated with Homo erectus populations<br />

in Africa. � ese distinctive oval and pearshaped<br />

hand axes have been found over a<br />

wide area, evidence that Acheulean tool users<br />

were <strong>the</strong> �rst to leave Africa and successfully<br />

colonise Eurasia. � is suggests that <strong>the</strong><br />

axes could be up to 700,000 years old. � e<br />

standard hypo<strong>the</strong>sis has been that Acheulean<br />

toolmakers reached Europe and Asia via <strong>the</strong><br />

Middle East, passing mainly through what is<br />

now Turkey into <strong>the</strong> Balkans. � ese new �nds<br />

suggest that <strong>the</strong>y did not only travel by land.<br />

It has been established that <strong>the</strong> earliest<br />

maritime travel was <strong>the</strong> sea crossing of early<br />

humans to Australia, which began about<br />

60,000 years ago. � ere is also some evidence<br />

of early hominids travelling by water to new<br />

habitats, particularly <strong>the</strong> Indonesian island<br />

of Flores, where skeletons and artefacts<br />

associated with so-called ‘hobbits’ have<br />

been found. � e research <strong>from</strong> Crete, if<br />

con�rmed by fur<strong>the</strong>r study, could provide an<br />

entirely new timeline of human and hominid<br />

mobility.<br />

Sophie Mackenzie<br />

Accessing <strong>the</strong><br />

Tombs of Jebel<br />

Hafit<br />

In <strong>the</strong> south-east of <strong>the</strong> United Arab<br />

Emirates, near <strong>the</strong> city of Al Ain, stands<br />

Jebel Ha�t, a mountain that <strong>rises</strong> more<br />

than 1200m above sea level and straddles<br />

<strong>the</strong> border between <strong>the</strong> UAE and Oman.<br />

� e mountain also lends its name to <strong>the</strong><br />

early Bronze Age tombs that have been<br />

found on <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn and eastern slopes.<br />

More than 500 of <strong>the</strong>se beehive-shaped<br />

tombs have been found in <strong>the</strong> area, <strong>the</strong><br />

largest of which originally stood 4m in<br />

height. Dating to c. 3200 - 2700 BC, <strong>the</strong><br />

Ha�t Tombs were constructed <strong>from</strong> locally<br />

quarried stone.<br />

� e tombs had been stripped almost<br />

bare by millennia of looting, and, until<br />

scienti�c testing is carried out on <strong>the</strong> small<br />

number of human skeletal remains found<br />

within a few of <strong>the</strong> tombs, it cannot be<br />

con�rmed if <strong>the</strong> bones belong to those<br />

originally buried in <strong>the</strong> tombs or are those<br />

of peoples who reused <strong>the</strong> structures<br />

during later periods. Finds of polychrome<br />

pottery discovered in some of <strong>the</strong> tombs<br />

indicate that <strong>the</strong> tomb builders had links<br />

with <strong>the</strong> wider Middle East with <strong>the</strong><br />

pottery produced at Jemdet Nasr near<br />

ancient Babylon between c.3200-2900 BC,<br />

and <strong>the</strong>refore suggest trading contacts<br />

that connected Arabia and sou<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

Mesopotamia during <strong>the</strong> early Bronze Age.<br />

Dr al Naboodah, Professor at United<br />

Arab Emirates University, Al Ain, says<br />

that, during <strong>the</strong> Early Bronze Age: ‘� e<br />

area was… a bustling farmland on <strong>the</strong><br />

route of a caravan. So it is very likely <strong>the</strong>re<br />

were immigrants and in�uences <strong>from</strong><br />

Mesopotamia and <strong>the</strong> ancient Egyptians<br />

that introduced di�erent kinds of gods<br />

and deities as well as religious rituals that<br />

spread throughout <strong>the</strong> Arabian Peninsula.’<br />

Until very recently this region was a<br />

military-controlled area, strewn with<br />

landmines and inaccessible to both<br />

archaeologists and interested tourists.<br />

However, in preparation for <strong>the</strong> building<br />

of a new resort complex, <strong>the</strong> mines and<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r military ordnance has been cleared<br />

away and, with <strong>the</strong> help of a 4x4 o�-road<br />

vehicle, visitors can now access <strong>the</strong> site.<br />

Although <strong>the</strong> majority of <strong>the</strong> tombs located<br />

on <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn side of Jebel Ha�t have<br />

been destroyed by recent construction,<br />

<strong>the</strong> structures that survive on <strong>the</strong> eastern<br />

�anks of <strong>the</strong> mountain are now protected<br />

by <strong>the</strong> Department of Antiquities and<br />

Tourism, while some of <strong>the</strong> tombs<br />

have also been undergoing a process of<br />

restoration.<br />

Benazir Siddique<br />

London School of Economics and Politics,<br />

Dubai<br />

3

in<strong>the</strong>news<br />

A new non-destructive<br />

method of radiocarbon dating<br />

At <strong>the</strong> 239 th National Meeting of <strong>the</strong> American<br />

Chemical Society, held in San Francisco <strong>from</strong><br />

21-25 March, research into a new form of radiocarbon<br />

dating has been revealed. The technique<br />

offers <strong>the</strong> potential to revolutionise our ability to<br />

assign extremely accurate dates to archaeological<br />

artefacts.<br />

Since being developed by Dr Willard Libby in<br />

1949, radiocarbon dating has been one of <strong>the</strong> most<br />

useful scientific tools available to archaeologists,<br />

allowing organic material to be dated by determining<br />

its content of carbon 14 (C 14 ). However,<br />

<strong>the</strong> method of testing has always necessitated <strong>the</strong><br />

destruction of <strong>the</strong> material undergoing study.<br />

Although today only tiny samples are required in<br />

order to test <strong>the</strong> age of an object, any destruction<br />

of archaeological treasures.<br />

By contrast, <strong>the</strong> new dating method removes <strong>the</strong><br />

need for <strong>the</strong> sample material to undergo destructive<br />

acid-base washes and incineration. Instead <strong>the</strong><br />

entire object is placed in a special chamber filled<br />

with electrically charged gas, a plasma that gently<br />

oxidises <strong>the</strong> surface of <strong>the</strong> artefact to produce carbon<br />

dioxide for C 14 analysis.<br />

The research was led by Prof Marvin Rowe <strong>from</strong><br />

Texas A&M University, College Station, who, with<br />

a research team <strong>from</strong> a branch of <strong>the</strong> university<br />

based in Qatar, developed <strong>the</strong> new dating method.<br />

According to Prof Rowe, ‘This technique stands to<br />

revolutionise radiocarbon dating. It expands <strong>the</strong><br />

possibility for analysing extensive museum collections<br />

that have previously been off limits because<br />

of <strong>the</strong>ir rarity or intrinsic value and <strong>the</strong> destructive<br />

nature of <strong>the</strong> current method of radiocarbon<br />

dating.’<br />

Rowe and <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r researchers have used <strong>the</strong><br />

new dating method to obtain <strong>the</strong> age of about<br />

20 different artefacts, including a section <strong>from</strong> a<br />

medieval Egyptian textile. In every case, <strong>the</strong> results<br />

obtained <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> new non-destructive dating<br />

technique match those derived <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> conventional<br />

C 14 sampling method.<br />

Even before <strong>the</strong> conference in San Francisco had<br />

come to an end, <strong>the</strong>re was speculation that <strong>the</strong> new<br />

technique could be used to date <strong>the</strong> Turin Shroud,<br />

<strong>the</strong> most famous and controversial artefact ever<br />

to have been radiocarbon dated. Prof Rowe noted<br />

that, in <strong>the</strong>ory, it could be used for this purpose.<br />

The linen cloth, believed by <strong>the</strong> Roman Catholic<br />

Church to be <strong>the</strong> burial shroud of Jesus Christ,<br />

underwent C 14 dating in 1988, when three separate<br />

laboratories reached <strong>the</strong> conclusion that <strong>the</strong><br />

shroud was a medieval fake produced between AD<br />

1260 - 1390. The results of <strong>the</strong> tests carried out 22<br />

years ago have, however, been questioned by some<br />

scholars, who argue that <strong>the</strong> material was taken<br />

<strong>from</strong> a medieval patch sewn on to <strong>the</strong> much earlier<br />

shroud. The new dating technique offers <strong>the</strong><br />

possibility of re-testing <strong>the</strong> shroud, and indeed a<br />

great many o<strong>the</strong>r precious artefacts, so as to provide<br />

a definitive date and finally bring an end to<br />

<strong>the</strong> speculation regarding this and o<strong>the</strong>r archaeological<br />

objects.<br />

James Beresford<br />

Claims of infant sacrifice in ancient<br />

A study led by University of Pittsburgh<br />

researchers could finally lay to rest <strong>the</strong><br />

conjecture that <strong>the</strong> ancient empire of<br />

Carthage regularly sacrificed its youngest<br />

citizens. An examination of <strong>the</strong> remains of<br />

Carthaginian children revealed that most<br />

infants perished prenatally or very shortly<br />

after birth and were unlikely to have lived<br />

long enough to be sacrificed, according to a<br />

report in <strong>the</strong> online journal PLoS ONE.<br />

The findings, based on analysis of skeletal<br />

remains found in Carthaginian burial<br />

urns, refute claims <strong>from</strong> as early as <strong>the</strong> 3 rd<br />

century BC of systematic infant sacrifice<br />

at Carthage, according to lead researcher<br />

Jeffrey H. Schwartz, a Professor at Pitt’s<br />

School of Arts and Sciences. Prof Schwartz<br />

and his colleagues present <strong>the</strong> more<br />

The tophet burial grounds, Carthage (modern<br />

Tunis). Photo: courtesy Johnny Shaw<br />

damage<br />

On 30 March, firefighters were called<br />

to <strong>the</strong> Golden House of Nero, <strong>the</strong><br />

Domus Aurea, after <strong>the</strong> ceiling suffered<br />

partial collapse. The Domus Aurea<br />

gained its name <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> extensive use<br />

of gold-leaf in <strong>the</strong> decoration of <strong>the</strong><br />

palace. As well as frescoes painted on<br />

<strong>the</strong> walls, <strong>the</strong> walls and ceilings were<br />

also adorned with panels of ivory and<br />

semi-precious stones.<br />

Construction of <strong>the</strong> palace began<br />

on <strong>the</strong> slopes of <strong>the</strong> Esquiline Hill<br />

following <strong>the</strong> Great Fire which<br />

swept through Rome in AD 64, and<br />

<strong>the</strong> building was completed four<br />

years later, just before Nero’s death.<br />

Although most of <strong>the</strong> 80 hectare site<br />

was soon dismantled by Vespasian,<br />

about 150 rooms survived.<br />

The Golden House has been one of<br />

<strong>the</strong> most popular tourist attractions<br />

in Rome since it was reopened in<br />

1999. However, <strong>the</strong> palace was closed<br />

throughout most of <strong>the</strong> 1980s and<br />

1990s because of concerns over<br />

<strong>the</strong> safety of <strong>the</strong> structure. Since its<br />

reopening, it has continued to be<br />

prone to closure, with structural<br />

problems and water infiltration, with<br />

a section of <strong>the</strong> ceiling collapsing in<br />

2001.<br />

James Beresford<br />

benign interpretation that very young Punic<br />

children were cremated and interred in<br />

burial urns regardless of how <strong>the</strong>y died.<br />

Writing in <strong>the</strong> 1 st century BC, <strong>the</strong> Greek<br />

historian Diodorus Siculus wrote of how,<br />

‘In former times <strong>the</strong>y [Carthaginians]<br />

had been accustomed to sacrifice… <strong>the</strong><br />

noblest of <strong>the</strong>ir sons, but more recently,<br />

secretly buying and nurturing children,<br />

<strong>the</strong>y had sent <strong>the</strong>se to <strong>the</strong> sacrifice’ (Library<br />

of History, 20.14). However, according<br />

to Prof Schwartz, ‘Our study emphasises<br />

that historical scientists must consider all<br />

evidence when deciphering ancient societal<br />

behaviour. The idea of infant sacrifice<br />

in Carthage is not based on a study of<br />

cremated remains, but on instances of<br />

human sacrifice reported by a few ancient<br />

chroniclers, inferred <strong>from</strong> ambiguous<br />

inscriptions, and referenced in <strong>the</strong> Old<br />

Testament. Our results show that some<br />

4 <strong>Minerva</strong> May/June 2010

The Medusa in <strong>Caesar</strong>ea<br />

Art is a very useful index of <strong>the</strong> spread of<br />

mythology and artistic taste in <strong>the</strong> Roman<br />

Empire. This is especially true of Medusa, one<br />

of <strong>the</strong> three gorgon sisters, who had snakes for<br />

hair and – according to Graeco-Roman myth –<br />

could turn those who looked at her into stone.<br />

Medusa is depicted in stone as <strong>the</strong> centrepiece<br />

of a new open-air exhibition in nor<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

Israel, ‘Medusas in <strong>Caesar</strong>ea Harbour’.<br />

Medusa was a common motif in Roman<br />

art, appearing on bronzes, floor mosaics,<br />

architectural sculpture, and military<br />

paraphernalia – <strong>the</strong> Gorgoneion – to ward off<br />

evil and enemies. This fine example, dating<br />

to <strong>the</strong> 3 rd century AD, also contains motifs<br />

of <strong>the</strong>atrical masks – perhaps intended to<br />

entertain in <strong>the</strong> afterlife – and was recovered in<br />

<strong>the</strong> course of extensive excavations conducted<br />

in a necropolis adjacent to <strong>the</strong> ancient city. It<br />

weighs a staggering four tonnes. Sarcophagi of<br />

this character were unique to elite members of<br />

society, and it may have contained <strong>the</strong> remains<br />

of a local official, a female aristocrat, or a<br />

member of <strong>the</strong> priesthood. The ethnicity of <strong>the</strong><br />

sarcophagus’s occupant is unclear, but because<br />

<strong>the</strong> originally pagan practice of interment<br />

in sarcophagi later spread to all religions in<br />

<strong>the</strong> region, he or she could have been pagan,<br />

Jewish, Samaritan, or even Christian.<br />

<strong>Caesar</strong>ea emerged as a flourishing<br />

Hellenised urban centre <strong>from</strong> 22 BC onwards<br />

under Herod <strong>the</strong> Great, who dedicated <strong>the</strong><br />

former city of Straton’s Tower to his great<br />

patron Augustus (r. 27 BC – AD 14). The<br />

city was capital of Judea and of <strong>the</strong> province<br />

Carthage debunked<br />

children were sacrificed, but contradict <strong>the</strong><br />

conclusion that Carthaginians regularly<br />

sacrificed <strong>the</strong>ir own children.’<br />

Schwartz and his colleagues analysed<br />

<strong>the</strong> remains of children found in tophets,<br />

burial sites peripheral to conventional<br />

Carthaginian cemeteries for older children<br />

and adults. Tophets housed urns containing<br />

<strong>the</strong> cremated remains of young children<br />

and animals, which led to <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory that<br />

<strong>the</strong>y were reserved for victims of sacrifice.<br />

The researchers examined <strong>the</strong> skeletal<br />

remains <strong>from</strong> 348 urns for developmental<br />

markers that would determine <strong>the</strong> children’s<br />

age at death. Schwartz and Houghton<br />

recorded skull, hip, long bone and tooth<br />

measurements, which indicated that most<br />

of <strong>the</strong> children died in <strong>the</strong>ir first year, with<br />

a sizeable number aged only two to five<br />

months, and that at least 20 percent of <strong>the</strong><br />

sample was prenatal.<br />

<strong>Minerva</strong> May/June 2010<br />

Marble sarcophagus lid carved with a bas-relief depicting Medusa, 3 rd century AD.<br />

Photo: courtesy of <strong>the</strong> Israel Antiquities Authority.<br />

of Palaestina Prima after <strong>the</strong> reforms of<br />

Diocletian (r. AD 284 - 305). O<strong>the</strong>r finds<br />

displayed in <strong>the</strong> current exhibition include<br />

a piece of building fabric with a dedicatory<br />

inscription by a female named Cleopatra, and<br />

a sarcophagus with an inscription dedicated<br />

by Eliphis to his wife Manophila. Dedicatory<br />

Schwartz and Houghton <strong>the</strong>n selected<br />

teeth <strong>from</strong> 50 individuals <strong>the</strong>y concluded<br />

had died before or shortly after birth,<br />

and examined <strong>the</strong>se for a neonatal line.<br />

This opaque band forms in human teeth<br />

between <strong>the</strong> interruption of enamel<br />

production at birth and its resumption<br />

within two weeks of life, and is used to<br />

determine an infant’s age at death. A<br />

neonatal line was present in <strong>the</strong> teeth of 24<br />

individuals, meaning <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs had died<br />

prenatally or within two weeks of birth.<br />

The contents of <strong>the</strong> urns also dispel<br />

<strong>the</strong> possibility of mass infant sacrifice, as<br />

none contained enough skeletal material<br />

to suggest <strong>the</strong> presence of more than two<br />

complete individuals. Although many urns<br />

contained some superfluous fragments<br />

belonging to additional children, <strong>the</strong><br />

researchers concluded that <strong>the</strong>se bones<br />

remained <strong>from</strong> previous cremations.<br />

inscriptions of this character are commonly<br />

found in <strong>the</strong> Romano-Byzantine Levant and<br />

provide an informative index of family ties<br />

and patronage. This is <strong>the</strong> first of several<br />

planned exhibitions in <strong>the</strong> harbour compound<br />

at <strong>Caesar</strong>ea.<br />

Dr Mark Merrony<br />

The team’s report also disputes <strong>the</strong><br />

contention that Carthaginians specifically<br />

sacrificed first-born males. Schwartz and<br />

Houghton determined sex by measuring<br />

<strong>the</strong> sciatic notch (a crevice at <strong>the</strong> rear of<br />

<strong>the</strong> pelvis that is wider in females) of 70<br />

hip bones. They discovered that 38 pelvises<br />

came <strong>from</strong> females and 26 <strong>from</strong> males.<br />

Two o<strong>the</strong>rs were likely to be female, one<br />

probably male, and three undetermined.<br />

Schwartz and his colleagues conclude<br />

that <strong>the</strong> high incidence of prenatal and<br />

infant mortality are consistent with modern<br />

data on stillbirths, miscarriages and infant<br />

death. If conditions in o<strong>the</strong>r ancient cities<br />

were comparable with Carthage, young<br />

and unborn children could have easily<br />

succumbed to <strong>the</strong> diseases and sanitary<br />

shortcomings found in such cities as Rome<br />

and Pompeii.<br />

Sophie Mackenzie<br />

5

in<strong>the</strong>news<br />

The ‘golden bough’ is found in Italy<br />

Italian archaeologists claim to have found a stone enclosure<br />

that once protected <strong>the</strong> legendary ‘golden bough’. The<br />

discovery was made whilst excavating a sanctuary in <strong>the</strong><br />

Alban hills north of Rome, by a team led by Filippo Coarelli,<br />

a recently retired Professor of archaeology at Perugia<br />

University. The researchers believe that <strong>the</strong> enclosure was<br />

built by <strong>the</strong> Latins to protect a large cypress or oak tree. The<br />

stone enclosure is in <strong>the</strong> middle of an area that contains<br />

<strong>the</strong> ruins of an immense sanctuary dedicated to Diana, <strong>the</strong><br />

goddess of hunting. Finds of pottery fragments dating to<br />

<strong>the</strong> 13 th or 12 th centuries BC indicate that <strong>the</strong> site was in use<br />

during <strong>the</strong> mid or late Italian Bronze Age.<br />

Prof Christopher Smith, <strong>the</strong> head of <strong>the</strong> British School<br />

at Rome, commented: ‘It’s an intriguing discovery and<br />

adds evidence to <strong>the</strong> fact that this was an extraordinarily<br />

important sanctuary.’<br />

In <strong>the</strong> Aeneid, Virgil tells of <strong>the</strong> Trojan hero Aeneas’<br />

journey to <strong>the</strong> underworld. Anchises, Aeneas’ dead fa<strong>the</strong>r,<br />

appears to his son to tell him to visit <strong>the</strong> underworld, where<br />

he will learn what <strong>the</strong> future holds for his people. Aeneas<br />

must first find <strong>the</strong> oracle Sibyl of Cumae, who will lead<br />

him to <strong>the</strong> land of <strong>the</strong> dead – but she informs him that he<br />

cannot pass through <strong>the</strong> underworld without <strong>the</strong> golden<br />

bough. Two doves lead him through <strong>the</strong> forest to an oak<br />

tree bearing a sacred branch, and he and <strong>the</strong> Sibyl enter<br />

<strong>the</strong> underworld toge<strong>the</strong>r. The bough allows <strong>the</strong> hero to<br />

pass safely through various hazards, and be taken by <strong>the</strong><br />

boatman Charon across River Acheron to <strong>the</strong> kingdom of<br />

Hades. There he finds <strong>the</strong> spirit of his fa<strong>the</strong>r.<br />

The sacred oak branch described in <strong>the</strong> Aeneas myth also<br />

gives its name to The Golden Bough, a highly influential<br />

study of myth and religion published in 1890 by Sir James<br />

Frazer (1854-1941).<br />

Sophie Mackenzie<br />

The Museum of Classical Archaeology at<br />

Cambridge reopened to <strong>the</strong> public in April.<br />

With more than 600 plaster casts of Graeco-<br />

Roman sculpture, of which 450 are on<br />

display, <strong>the</strong> collection is one of <strong>the</strong> largest of<br />

ancient statuary in <strong>the</strong> world. First opened<br />

in 1884, <strong>the</strong> museum provides an invaluable<br />

resource for students <strong>from</strong> Cambridge<br />

University, specialists and <strong>the</strong> public.<br />

Although none of <strong>the</strong> works of art on show<br />

are original, all <strong>the</strong> sculptures, reliefs, vases,<br />

and shards of pottery are accurate replicas<br />

cast <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> originals, allowing most of <strong>the</strong><br />

great sculptures created during antiquity to<br />

be viewed toge<strong>the</strong>r in a single location.<br />

The collection is important not only as a<br />

teaching tool, but because it preserves <strong>the</strong><br />

form of artworks that have subsequently<br />

been destroyed or damaged. For example,<br />

<strong>the</strong> Lysicrates Monument in A<strong>the</strong>ns, built<br />

In <strong>the</strong> neighb’ring grove<br />

There stands a tree; <strong>the</strong> queen of Stygian Jove<br />

Claims it her own; thick woods and gloomy night<br />

Conceal <strong>the</strong> happy plant <strong>from</strong> human sight.<br />

One bough it bears; but (wondrous to behold!)<br />

The ductile rind and leaves of radiant gold:<br />

This <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> vulgar branches must be torn…<br />

Cambridge cast gallery reopens<br />

in 334 BC, has become gravely eroded as a<br />

result of <strong>the</strong> city’s air pollution over <strong>the</strong> past<br />

century. The museum’s copy, cast in <strong>the</strong> 18 th<br />

century, preserves some of <strong>the</strong> figures that<br />

have been worn away <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> late Classical<br />

monument, allowing researchers a better<br />

understanding of <strong>the</strong> monument than <strong>from</strong><br />

study of <strong>the</strong> original.<br />

One of <strong>the</strong> most famous casts in <strong>the</strong><br />

museum is that of <strong>the</strong> Peplos Kore. While<br />

<strong>the</strong> original statue, carved <strong>from</strong> white<br />

Parian marble, stands in <strong>the</strong> recently opened<br />

Acropolis Museum in A<strong>the</strong>ns (see <strong>Minerva</strong>,<br />

November/December 2009, pp. 8-11), <strong>the</strong><br />

cast at Cambridge is presented in <strong>the</strong> vibrant<br />

colours that were painted on <strong>the</strong> statue when<br />

it was first erected on <strong>the</strong> A<strong>the</strong>nian Acropolis<br />

in c. 530 BC. The cast <strong>the</strong>refore provides a<br />

good impression of how <strong>the</strong> sculpture was<br />

originally intended to be viewed when it was<br />

created during <strong>the</strong> Archaic period.<br />

The reproductions in <strong>the</strong> museum also<br />

allow sections of statues that have become<br />

broken and separated over <strong>the</strong> years to be<br />

reunited. A plaster cast of ano<strong>the</strong>r Archaic<br />

kore <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> Acropolis of A<strong>the</strong>ns – known<br />

as <strong>the</strong> Lyon kore because <strong>the</strong> upper body<br />

and head are in <strong>the</strong> French city – is reunited<br />

in cast form at Cambridge with <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

surviving pieces of <strong>the</strong> statue, which are<br />

currently on display in <strong>the</strong> Greek capital.<br />

The Museum of Classical Art is housed in<br />

<strong>the</strong> Classics Faculty building on Sidgwick<br />

Avenue, Cambridge. Entrance to <strong>the</strong> museum<br />

is free.<br />

For fur<strong>the</strong>r information about <strong>the</strong><br />

museum, and access to <strong>the</strong> online database<br />

of <strong>the</strong> collection of casts, visit http://www.<br />

classics.cam.ac.uk/museum/<br />

James Beresford<br />

6 <strong>Minerva</strong> May/June 2010

Roman<br />

aqueduct<br />

unear<strong>the</strong>d<br />

in Jerusalem<br />

A team of archaeologists has recently<br />

identified a large section of <strong>the</strong> high-level<br />

aqueduct system that supplied <strong>the</strong> Roman<br />

city of Jerusalem. The find was made under<br />

<strong>the</strong> direction of Dr Ofer Sion as part of an<br />

excavation conducted under <strong>the</strong> auspices of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) in <strong>the</strong><br />

area inside <strong>the</strong> Jaffa Gate in <strong>the</strong> west of <strong>the</strong> Old<br />

City. The section of aqueduct is 1.5m above <strong>the</strong><br />

original ground level, with an internal conduit<br />

width of 60cm, and is preserved for 40m in<br />

length with inspection shafts placed at 15m<br />

intervals – a characteristic of many Roman<br />

aqueducts for purposes of maintenance (often<br />

to clear limescale, known as sinter in civil<br />

engineering terms).<br />

Sion and his colleagues have confirmed that<br />

this section of aqueduct corresponds to <strong>the</strong><br />

EGyPT NEWS<br />

Discovery of <strong>the</strong> remains of Queen<br />

Behenu’s pyramid at Saqqara<br />

French archaeologists excavating at Saqqara, in <strong>the</strong> necropolis<br />

of <strong>the</strong> 6 th dynasty pharaoh Pepi I (reigned c. 2332 - 2283 BC)<br />

have discovered <strong>the</strong> tomb of queen Behenu, containing an intact<br />

sarcophagus within. Although it has not yet been confirmed, it<br />

is thought Behenu was one of several wives of Pepi II (reigned c.<br />

2278 - 2184 BC), who, on succeeding Merenre (c. 2283 - 2278<br />

BC) to <strong>the</strong> throne as an infant, is recorded as reigning for 94<br />

years, <strong>the</strong> longest of any pharaoh.<br />

Also discovered by <strong>the</strong> archaeologists were <strong>the</strong> broken and<br />

scattered remains of Pyramid Texts belonging to <strong>the</strong> Queen.<br />

These focused on rituals concerning <strong>the</strong> resurrection and<br />

afterlife. Only 11 o<strong>the</strong>r tombs have been found containing <strong>the</strong>se<br />

texts, <strong>the</strong> earliest religious writing in Egypt. The importance of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Pyramid Texts was stressed by Philippe Collombert, who<br />

heads <strong>the</strong> mission sponsored by <strong>the</strong> French Ministry of Foreign<br />

Affairs: ‘Pyramid Texts are <strong>the</strong> first compass of writing in <strong>the</strong><br />

world. This is <strong>the</strong> very first huge grouping of text in <strong>the</strong> history<br />

of <strong>the</strong> world. That’s why it’s so important to find <strong>the</strong>se Pyramid<br />

Texts, even if <strong>the</strong>y’re <strong>the</strong> same as those found in o<strong>the</strong>r pyramids.<br />

Sometimes one sentence will change and some new words and<br />

sentences will appear with formulas for <strong>the</strong> afterlife.’<br />

Unfortunately, Behenu’s pyramid, like most of <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs<br />

located at <strong>the</strong> necropolis, was heavily damaged during <strong>the</strong><br />

Mamluk period (c. AD 1250 - 1517), when <strong>the</strong> limestone<br />

casings were removed and stone was quarried <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> funerary<br />

chambers, often leaving little more than a mound of rubble for<br />

archaeologists to investigate.<br />

<strong>Minerva</strong> May/June 2010<br />

Section of Roman aqueduct channel recently discovered near <strong>the</strong> Jaffa Gate in Jerusalem,<br />

2 nd century AD. Photo: Assaf Peretz, courtesy of <strong>the</strong> Israel Antiquities Authority.<br />

water conduit identified by German architect,<br />

archaeologist and Protestant missionary Dr<br />

Conrad Schick in advance of construction<br />

work in 1898. Originally, <strong>the</strong> channel formed<br />

part of <strong>the</strong> high-level aqueduct system that<br />

supplied water to <strong>the</strong> Palace of King Herod and<br />

<strong>the</strong> Pool of Hezekiah. The low-level aqueduct<br />

fed water to <strong>the</strong> area of <strong>the</strong> Second Temple and<br />

supplied <strong>the</strong> Pools of Be<strong>the</strong>sda and Siloam –<br />

now attested archaeologically – where Jesus is<br />

known to have carried out his healings in <strong>the</strong><br />

days prior to <strong>the</strong> Crucifixion (see <strong>Minerva</strong>,<br />

July/August 2009, pp. 19-23).<br />

It has been ascertained that <strong>the</strong> high-level<br />

channel was part of <strong>the</strong> new system supplying<br />

<strong>the</strong> city rebuilt by Hadrian (r. AD 117-138)<br />

as Aelia Capitolina after it was razed in <strong>the</strong><br />

Bar Kokhba Revolt of AD 135. Both branches<br />

of <strong>the</strong> system were supplied by Solomon’s<br />

Pools, three impressive cisterns located 5km<br />

south-west of Bethlehem – incorrectly named<br />

after <strong>the</strong> biblical king. These had a combined<br />

capacity of an estimated 200 million litres<br />

and were supplied by a series of underground<br />

springs. The cisterns were configured as a<br />

cascade system, with a height differential of<br />

6m, and were fed by a rock-cut tunnel and<br />

connected to <strong>the</strong> Jerusalem supply lines in<br />

<strong>the</strong> same manner. Collectively, this ingenious<br />

system represents yet ano<strong>the</strong>r magnificent<br />

achievement of Roman civil engineering.<br />

Dr Mark Merrony<br />

Funerary temple statues discovered<br />

at Kom el-Hettan<br />

It was announced in late March that two statues had been<br />

discovered during routine work being carried out to reduce<br />

groundwater levels close to <strong>the</strong> funerary temple of Amenhotep III<br />

(reigned c. 1386 -1349 BC) at Kom el-Hettan on <strong>the</strong> west bank<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Nile near Luxor. Both statues were carved <strong>from</strong> red granite,<br />

<strong>the</strong> first depicting Amenhotep toge<strong>the</strong>r with <strong>the</strong> god Re-Horakhty,<br />

while <strong>the</strong> second is of <strong>the</strong> god of wisdom, Thoth, shown with<br />

<strong>the</strong> head of a baboon. A large fragment of a statue carved <strong>from</strong><br />

calcite was also unear<strong>the</strong>d during <strong>the</strong> maintenance work, and<br />

has also been tentatively identified as dating to <strong>the</strong> reign of<br />

Amenhotep III. Excavations in <strong>the</strong> area around Kom el-Hettan will<br />

remain in progress in <strong>the</strong> hope of recovering additional statues<br />

that were once placed within <strong>the</strong> funerary temple.<br />

Registering Egypt’s privately owned<br />

antiquities<br />

In order to meet new government regulations concerning <strong>the</strong><br />

ownership of antiquities by Egyptians (see <strong>Minerva</strong>, March/April,<br />

p.7), on 10 March <strong>the</strong> country’s Culture Minister announced<br />

<strong>the</strong> setting up of a committee that will inspect and register any<br />

privately owned artefacts. Under <strong>the</strong> terms of <strong>the</strong> new legislation,<br />

which was brought into effect at <strong>the</strong> start of February to reinforce<br />

<strong>the</strong> country’s ban on <strong>the</strong> trade in antiquities, Egyptians who<br />

possess historic artefacts must register <strong>the</strong>m with <strong>the</strong> committee,<br />

which is affiliated to <strong>the</strong> Supreme Council of Antiquities.<br />

James Beresford<br />

7

New Kingdom royalty<br />

Tutankhamun’s<br />

Tutankhamun was a clubfooted,<br />

inbred teenager with<br />

a cleft palate, who probably<br />

died as a result of an infection<br />

<strong>from</strong> a broken leg and complications<br />

resulting <strong>from</strong> malaria. These are<br />

just some of <strong>the</strong> long-awaited findings<br />

of a study undertaken in Egypt over <strong>the</strong><br />

last two years. Using <strong>the</strong> latest scientific<br />

procedures, <strong>the</strong> objective of <strong>the</strong> study<br />

was first to discover <strong>the</strong> much-debated<br />

reasons behind <strong>the</strong> early death of<br />

Tutankhamun. Secondly, <strong>the</strong> researchers<br />

set out to unravel <strong>the</strong> complicated<br />

and highly incestuous family lineage<br />

of <strong>the</strong> young pharaoh and <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

royal members of <strong>the</strong> 18 th dynasty who<br />

ruled Egypt’s New Kingdom <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

mid 16 th through to <strong>the</strong> beginning of<br />

<strong>the</strong> 13 th century BC. While not without<br />

8<br />

DNA<br />

James Beresford reviews recently<br />

published results of a two-year<br />

research programme analysing<br />

<strong>the</strong> teenage pharaoh and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

members of New Kingdom royalty<br />

Fig 1. The gold<br />

death mask <strong>from</strong><br />

Tutankhamun’s middle<br />

coffin, Cairo Museum.<br />

Photo: D. Williams.<br />

Fig 2. Dr Hawass<br />

(left) and his team of<br />

researchers extracting<br />

DNA <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> mummy<br />

of Tutankhamen.<br />

Photo: The Press<br />

Association.<br />

1<br />

its critics, <strong>the</strong> new research has offered<br />

some extremely interesting findings<br />

that will be scrutinised by scientists<br />

long into <strong>the</strong> future.<br />

In addition to Tutankhamun, ten<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r royal mummies, known or<br />

believed to have been closely related<br />

to <strong>the</strong> young pharaoh, were also examined.<br />

The remains of an additional<br />

five mummies dating to <strong>the</strong> early New<br />

Kingdom were also included in <strong>the</strong><br />

study to act as a control group. All 16<br />

mummies were subjected to detailed<br />

study, with <strong>the</strong> results released in<br />

<strong>the</strong> Journal of <strong>the</strong> American Medical<br />

Association (JAMA) in February, while<br />

<strong>the</strong> leader of <strong>the</strong> research team, Dr Zahi<br />

Hawass, Secretary-General of Egypt’s<br />

Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA),<br />

also presented some of <strong>the</strong> more sensational<br />

results of <strong>the</strong> two-year study<br />

during a press conference.<br />

Using a Computed Tomography<br />

(CT) unit, 12 of <strong>the</strong> mummies held at<br />

Cairo Museum were scanned, as were<br />

those of Tutankhamun and two o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

bodies recovered <strong>from</strong> tomb KV35 in<br />

Luxor. (The only mummy not scanned<br />

was that of Ahmose-Nefertari, wife of<br />

pharaoh Ahmose I, c.1550-1525 BC.)<br />

Alongside <strong>the</strong> CT scans, a series of<br />

DNA tests was also carried out on all<br />

<strong>the</strong> mummies, except that of Thutmose<br />

II (c. 1493-1479 BC). Between two and<br />

four biopsies were performed on each<br />

mummy (Fig 2). Samples extracted<br />

<strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> bone tissues of <strong>the</strong> mummies<br />

underwent two types of analysis.<br />

Specific nuclear DNA sequences<br />

<strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> Y-chromosome – which is<br />

passed down through <strong>the</strong> male line,<br />

<strong>from</strong> fa<strong>the</strong>r to son – were tested in<br />

order to determine <strong>the</strong> paternal line.<br />

Alongside this, microsatellites were<br />

examined; <strong>the</strong>se repeated sequences<br />

of DNA acted as ‘genetic fingerprints’<br />

and allowed <strong>the</strong> researchers to trace<br />

<strong>the</strong> genealogy of many members of <strong>the</strong><br />

18 th dynasty, resulting in <strong>the</strong> production<br />

of a family tree for Tutankhamun<br />

that spanned five generations.<br />

That such an invasive procedure<br />

required to retrieve <strong>the</strong> DNA was<br />

carried out at all is remarkable. Dr<br />

Hawass himself has long been adamant<br />

that such examinations should<br />

not be inflicted on Egyptian mummies<br />

because DNA would not have<br />

survived <strong>the</strong> mummification process<br />

or <strong>the</strong> heat and humidity of thousands<br />

of years in an Egyptian tomb. A scientific<br />

paper published in <strong>the</strong> American<br />

2<br />

Journal of Physical Anthropology in<br />

2005 also summed up research into <strong>the</strong><br />

viability of DNA survival in ancient<br />

Egyptian mummies: ‘To conclude, we<br />

find that <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>rmal history of most,<br />

if not all, ancient Egyptian material<br />

argues against <strong>the</strong> recovery of DNA.<br />

Consequently, such claims should continue<br />

to be considered skeptically.’<br />

What may have helped persuade Dr<br />

Hawass and <strong>the</strong> SCA to undertake <strong>the</strong><br />

recent research was funding <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Discovery Channel (which also gained<br />

filming rights for <strong>the</strong> research), allowing<br />

<strong>the</strong> equipping of a new DNA laboratory<br />

at <strong>the</strong> Egyptian Museum in<br />

Cairo. The establishment of this new<br />

laboratory alongside <strong>the</strong> one at <strong>the</strong><br />

National Research Center in Cairo<br />

meant that DNA testing could be carried<br />

out independently at two different<br />

locations in <strong>the</strong> Egyptain capital<br />

without <strong>the</strong> need to involve any foreign<br />

institutions, a source of great pride for<br />

<strong>the</strong> Egyptian scientists.<br />

More importantly, <strong>the</strong> use of two<br />

seperate laboratories eliminated any<br />

possibility of contamination of <strong>the</strong><br />

ancient DNA by <strong>the</strong> research staff<br />

affecting <strong>the</strong> final results. According to<br />

<strong>the</strong> report in <strong>the</strong> JAMA, ‘because <strong>the</strong><br />

[genetic] profile differed <strong>from</strong> those of<br />

<strong>the</strong> laboratory staff and were not identical<br />

to <strong>the</strong> ones established for <strong>the</strong><br />

control group [of mummies] <strong>the</strong> data<br />

were considered au<strong>the</strong>ntic’. The fact <strong>the</strong><br />

DNA was extracted <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> bone also<br />

offered a greater chance that <strong>the</strong> samples<br />

would be free <strong>from</strong> contamination.<br />

Never<strong>the</strong>less, <strong>the</strong> long years in which<br />

<strong>the</strong> mummies have been poked, prodded,<br />

and sweated over by Egyptologists<br />

makes it difficult to rule out <strong>the</strong> possibility<br />

that modern DNA has permeated<br />

into <strong>the</strong> bone, corrupting <strong>the</strong> tests<br />

and leading to distorted results.<br />

Despite such concerns, <strong>the</strong> results<br />

<strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> DNA tests offer <strong>the</strong> chance to<br />

closely map Tutankhamun’s immediate<br />

<strong>Minerva</strong> May/June 2010

lineage. Perhaps <strong>the</strong> most momentous<br />

announcement of <strong>the</strong> entire project<br />

was that <strong>the</strong> DNA fingerprinting<br />

has allowed <strong>the</strong> researchers to conclude<br />

that <strong>the</strong> fa<strong>the</strong>r of <strong>the</strong> boy king<br />

was <strong>the</strong> unidentified mummy found in<br />

tomb KV55, and that <strong>the</strong> poorly preserved<br />

body is probably that of <strong>the</strong><br />

infamous heretic pharaoh, Akhenaten<br />

(Figs 4, 5). As Dr Hawass noted:<br />

‘The analysis proves conclusively that<br />

Tutankhamun’s fa<strong>the</strong>r was <strong>the</strong> mummy<br />

found in KV55. The project’s CT scan<br />

of this mummy provides an age at death<br />

of between 45 and 55 for this mummy.<br />

Most earlier forensic studies had put<br />

forth an age of 20-25, which would be<br />

too young for Akhenaten, who came to<br />

<strong>the</strong> throne as an adult and ruled for 17<br />

years. The new CT scan proves that this<br />

mummy is almost certainly Akhenaten<br />

himself… The DNA also traces a direct<br />

line <strong>from</strong> Tutankhamun through <strong>the</strong><br />

KV55 mummy to Akhenaten’s fa<strong>the</strong>r<br />

Amenhotep III.’<br />

Tomb KV55 – its entrance lying<br />

barely a dozen metres <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> opening<br />

to Tutankhamun’s tomb of KV62,<br />

– was found in 1907 by Edward Ayrton<br />

(Fig 6). Inside, both <strong>the</strong> walls of <strong>the</strong><br />

tomb and <strong>the</strong> mummy itself were badly<br />

damaged by water sepage, and identifying<br />

<strong>the</strong> body had been impossible<br />

because all <strong>the</strong> cartouches on <strong>the</strong> coffin<br />

had been obliterated. Originally<br />

thought to have been <strong>the</strong> body of Queen<br />

Tiye, <strong>the</strong> mummy was later identified<br />

as male and, until <strong>the</strong> latest research,<br />

had generally been linked to<br />

that of Smenkhkare, <strong>the</strong> little-known<br />

pharaoh who<br />

seems to have briefly succeeded<br />

to <strong>the</strong> throne on<br />

<strong>the</strong> death of Akhenaten.<br />

If <strong>the</strong> KV55 mummy<br />

is indeed that of<br />

Akhenaten, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong><br />

body of <strong>the</strong> most controversial<br />

pharaoh<br />

<strong>Minerva</strong> May/June 2010<br />

Fig 3. The Nor<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

Palace at <strong>the</strong> site<br />

of Amarna. Photo:<br />

James Beresford.<br />

Fig 4. Limestone<br />

profile of Akhenaten,<br />

c. 1350-1334 BC.<br />

Unknown provenance,<br />

H. 14.4cm. Neues<br />

Museum, Berlin. Photo:<br />

George Groutas.<br />

Fig 5. Sandstone<br />

statue of Akhenaten,<br />

c. 1350-1334 BC. H.<br />

124cm. Luxor Museum<br />

Photo: Oscar Dahl.<br />

5<br />

3<br />

ever to rule Egypt has finally been<br />

identified. This will put an end to years<br />

of speculation surrounding <strong>the</strong> final<br />

resting place of a king whose <strong>the</strong>ological<br />

focus on a single god, <strong>the</strong> Aten – <strong>the</strong><br />

worship of which was centered on <strong>the</strong><br />

newly created city at Amarna (Fig 3) –<br />

was a radical departure <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> traditional<br />

pan<strong>the</strong>on of deities controlled<br />

by <strong>the</strong> powerful priesthood in Thebes.<br />

The DNA testing also indicated that<br />

Tutankhamun’s mo<strong>the</strong>r was probably<br />

<strong>the</strong> ‘Younger Lady’ found in tomb<br />

KV35, and that she was of royal blood,<br />

probably <strong>the</strong> daughter of Amenhotep<br />

III and Queen Tiye. It would <strong>the</strong>refore<br />

appear that she was full sister as well as<br />

wife to Akhenaten. If this is confirmed,<br />

<strong>the</strong>n Tutankhamun’s family tree was<br />

extremely well pruned, a fact noted<br />

by Dr Hawass during his press conference:<br />

‘Tut’s only grand-parents, on both<br />

his paternal and maternal sides, were<br />

Amenhotep III and Tiye.’<br />

Such inbreeding may also explain<br />

<strong>the</strong> two stillborn foetuses discovered<br />

in Tutankhamun’s tomb by<br />

Howard Carter in 1922. Their mummified<br />

remains were among those<br />

included in <strong>the</strong> recent research study<br />

and indicate that <strong>the</strong>y were children<br />

of Tutankhamun, while <strong>the</strong>ir mo<strong>the</strong>r<br />

was probably <strong>the</strong> previously unidentified<br />

mummy found in KV21 in 1817.<br />

If this assumption is correct, <strong>the</strong>n<br />

this is almost certainly <strong>the</strong> body of<br />

Ankhesenamen, <strong>the</strong> queen and only<br />

known wife of Tutankhamun (Fig<br />

7). Ankhesenamen may have<br />

been a half-sister of<br />

Tutankhamun, fur<strong>the</strong>r<br />

‘evidence’ of<br />

<strong>the</strong> inbred nature of<br />

Egypt’s 18 th dynasty,<br />

and possibly a<br />

major reason for<br />

<strong>the</strong> stillbirth of <strong>the</strong><br />

two foetuses.<br />

However, if <strong>the</strong><br />

New Kingdom royalty<br />

4<br />

research team are correct in identifying<br />

Ankhesenamen and Tutankhamun<br />

as <strong>the</strong> parents of <strong>the</strong> two foetuses, <strong>the</strong>n<br />

<strong>the</strong> DNA results raise new problems.<br />

The genetic fingerprinting indicates<br />

that if <strong>the</strong> KV21 mummy is indeed<br />

Tutankhamun’s queen Ankhesenamen,<br />

<strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> DNA taken <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> remains<br />

of <strong>the</strong> two foetuses appears to show<br />

that <strong>the</strong> mummy in KV55, identified<br />

as Akhenaten, was not <strong>the</strong>ir maternal<br />

grandfa<strong>the</strong>r. If this is correct, <strong>the</strong>n<br />

ei<strong>the</strong>r Ankhesenamen was not <strong>the</strong><br />

mo<strong>the</strong>r of <strong>the</strong> stillborn babies in his<br />

tomb, or she was not <strong>the</strong> daughter<br />

of Akhenaten and his beautiful wife<br />

Nefertiti (Fig 8), despite <strong>the</strong> strong<br />

historical evidence in support of this<br />

being Ankhesenamen’s parentage.<br />

Instead of identifying <strong>the</strong> mummy<br />

<strong>from</strong> KV55 as that of Akhenaten, <strong>the</strong>re<br />

is a possibly that it is, as originally<br />

thought, <strong>the</strong> body of <strong>the</strong> enigmatic<br />

pharaoh Smenkhkare. If this is <strong>the</strong> case,<br />

<strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> DNA would seem to prove<br />

that Smenkhkare was <strong>the</strong> fa<strong>the</strong>r of<br />

Tutankhamun and, like Akhenaten, he<br />

was a son of Amenhotep III. However,<br />

given <strong>the</strong> inbreeding and incestuous<br />

nature of 18 th dynasty marriages, as<br />

9

New Kingdom royalty<br />

6 7<br />

well as <strong>the</strong> limited historical sources<br />

that survive <strong>from</strong> this period, constructing<br />

a family tree deciphering <strong>the</strong><br />

genetic data remains exceptionally difficult<br />

and will no doubt remain contentious<br />

well into <strong>the</strong> future.<br />

Akhenaten and o<strong>the</strong>r royalty<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Amarna period, including<br />

Tutankhamun, are often depicted<br />

with a strange and somewhat feminised<br />

physique (Figs 5, 7). This has<br />

led to speculation that male members<br />

of <strong>the</strong> royal family had a form of gynaecomastia<br />

which saw <strong>the</strong>m develop<br />

abnormally large mammary glands<br />

resulting in enlarged, female-like<br />

breasts. Scholars have also <strong>the</strong>orised<br />

that Akhenaten and Tutankhamun<br />

suffered <strong>from</strong> Marfan syndrome, a<br />

hereditary genetic disorder that will<br />

often cause elongated, slender arms<br />

and legs, and can produce o<strong>the</strong>r skeletal<br />

problems such as curvature of <strong>the</strong><br />

spine (scoliosis). Sufferers will sometimes<br />

also have ei<strong>the</strong>r an abnormally<br />

hollowed chest or, conversely, an<br />

abnormally protruding sternum.<br />

Such disorders have <strong>the</strong>refore<br />

been readily equated with many<br />

of <strong>the</strong> highly unusual physical<br />

features with which Akhenaten is<br />

portrayed.<br />

Unfortunately, even if <strong>the</strong><br />

recent study published in <strong>the</strong><br />

JAMA is correct in assuming<br />

that <strong>the</strong> KV55 mummy is<br />

Akhenaten, <strong>the</strong> poorly preserved<br />

skeletal remains make identifying<br />

physiological characteristics<br />

impossible. Similarly, because<br />

<strong>the</strong> front of Tutankhamun’s<br />

chest wall is missing, and his<br />

pelvic bones have also been<br />

removed, it is impossible to detect<br />

any traits associated with gynaecomastia<br />

or Marfan syndrome <strong>from</strong><br />

ei<strong>the</strong>r of <strong>the</strong> mummies. The researchers<br />

did carry out tests for dolichocephaly,<br />

which sometimes results <strong>from</strong><br />

Marfan syndrome and can cause<br />

10<br />

Fig 6. The Valley of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Kings on <strong>the</strong> west<br />

bank of <strong>the</strong> Nile near<br />

Luxor. Photo:<br />

Oscar Dahl.<br />

Fig 7. Back of<br />

<strong>the</strong> throne <strong>from</strong><br />

Tutankhamun’s tomb.<br />

The scene depicts<br />

<strong>the</strong> young pharaoh<br />

seated while his wife<br />

Ankhesenamen stands<br />

to <strong>the</strong> right. The rays<br />

of <strong>the</strong> sun disc, <strong>the</strong><br />

Aten, reach down <strong>from</strong><br />

above. Cairo Museum.<br />

Photo: D. Williams.<br />

Fig 8. Limestone<br />

and stucco bust of<br />

Nefertiti, sculptured<br />

c. 1345 BC by<br />

Thutmose at Amarna.<br />

H. 19cm. Neues<br />

Museum, Berlin. Photo:<br />

George Groutas.<br />

8<br />

<strong>the</strong> premature fusion of <strong>the</strong> sagittal<br />

suture on top of <strong>the</strong> skull, leading to<br />

<strong>the</strong> head becoming disproportionately<br />

long and narrow. This is reflected in<br />

<strong>the</strong> art of Amarna, in which <strong>the</strong> heads<br />

of Akhenaten and o<strong>the</strong>r royal members<br />

appear very elongated. However,<br />

CT scans revealed that nei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong><br />

skull of <strong>the</strong> KV55 mummy nor that of<br />

Tutankhamun exhibited any sign of <strong>the</strong><br />

sutures closing prematurely early. The<br />

researchers also measured <strong>the</strong> shape<br />

of both mummy skulls and found that,<br />

ra<strong>the</strong>r than being abnormally longheaded<br />

(dolichocephalic) both were<br />

in fact short-headed (brachycephalic).<br />

After testing all <strong>the</strong> mummies associated<br />

with <strong>the</strong> 18 th dynasty, <strong>the</strong> report<br />

in <strong>the</strong> JAMA emphasises that ‘a Marfan<br />

diagnosis cannot be supported in <strong>the</strong>se<br />

mummies’.<br />

The research did, however, reveal<br />

that Tutankhamun suffered <strong>from</strong> a<br />

bone disorder known as Köhler disease,<br />

which inhibits <strong>the</strong> flow of blood to <strong>the</strong><br />

feet. It was stressed by Dr Hawass during<br />

his press conference that: ‘The<br />

CT scan also revealed that <strong>the</strong><br />

king had a lame foot, caused<br />

by avascular bone necrosis.<br />

This conclusion is supported<br />

Egyptologically by<br />

<strong>the</strong> presence of over one hundred<br />

walking sticks in <strong>the</strong> tomb<br />

and by images of <strong>the</strong> king performing<br />

activities such as hunting<br />

while seated.’ Some scholars have<br />

claimed that <strong>the</strong> published images of<br />

<strong>the</strong> recent scans do not clearly lead to a<br />

diagnosis of a loss of blood flow (osteonecrosis)<br />

to two of <strong>the</strong> metatarsal bones<br />

of Tutankhamun’s left foot. Instead it<br />

has been suggested <strong>the</strong> deformities in<br />

<strong>the</strong> young pharaoh’s foot may be <strong>the</strong><br />

result of <strong>the</strong> embalming and mummification<br />

process. However, <strong>the</strong> reported<br />

signs of new bone growth in <strong>the</strong> foot as<br />

a reaction to <strong>the</strong> necrosis would appear<br />

to confirm that Tutankhamun suffered<br />

<strong>from</strong> osteonecrosis and had<br />

a lame foot. This disability may also<br />

explain <strong>the</strong> fracture in Tutankhamun’s<br />

left thigh – unhealed at <strong>the</strong> time of his<br />

death – which was discovered during<br />

a previous examination of <strong>the</strong> king’s<br />

body, a breakage that may have been<br />

<strong>the</strong> result of <strong>the</strong> pharaoh suffering a<br />

heavy fall through being unable to<br />

walk properly on his lame leg. While<br />

Dr Hawass may be correct in regarding<br />

<strong>the</strong> presence of 131 walking sticks<br />

in Tutankhamun’s tomb as a reflection<br />

of <strong>the</strong> pharaoh’s club foot, it is also possible<br />

that <strong>the</strong> canes primarily fulfilled<br />

ceremonial and symbolic ra<strong>the</strong>r than<br />

medical functions.<br />

The researchers concluded that <strong>the</strong><br />

osteonecrosis of Tutankhamun’s left<br />

foot and <strong>the</strong> fracture of his thigh, in<br />

combination with malarial infection,<br />