The Fight to Define Romans 13

Jeff Sessions used it to justify his policy of family separation, but he’s not the first to invoke the biblical passage.

On Thursday, Attorney General Jeff Sessions defended the Trump administration’s policy of separating immigrant children from their families at the border by referencing the New Testament. “I would cite you to the Apostle Paul and his clear and wise command in Romans 13,” Sessions said, “to obey the laws of the government because God has ordained them for the purpose of order.” White House Press Secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders summed up the same idea: “It is very biblical to enforce the law.”

Those remarks by Sessions were aimed at what he called “our church friends”—religious leaders who had criticized the policy of breaking up families. Sessions seemed to be speaking both as a public official and as an insider to Christianity. By invoking Romans 13, Sessions was bringing to bear one of the most significant biblical passages in American history, but one which is a “two-edged sword” of conflicting interpretations—and the interpretation that Sessions chose to stress has a troubling history.

Romans 13 is significant to American history because it played a critical role in the American Revolution. Loyalists who favored obedience to King and Parliament quoted Romans 13 for obvious reasons. “Let every soul be subject unto the higher powers,” the text read in the language of the time. A phrase later on in the passage has entered the English language: “The powers that be are ordained of God.” Law, order, and loyalty to an imperial government were all bound up in that phrase.

But surprisingly, political and religious leaders who favored the American Revolution were even more eager to quote Romans 13. Their reasoning turned on the justification that Paul gave for obeying government. Sessions said that government was created “for the purpose of order,” but Revolutionary clergy quoted Paul directly: “Rulers are not a terror to good works, but to the evil.” In a study of how the Bible was used in the American Revolution, the historian James Byrd argues that “American patriots” rejected against the notion that Romans 13 required unconditional obedience. Instead, he wrote, they preached from the text “to deny that Paul gave kings the right to be tyrants.” As the Anglican priest and regimental chaplain David Griffith said in a sermon on Romans 13, Paul “never meant … to give sanction to the crimes of wicked and despotic men.”

The Protestant clergy who favored the American Revolution were heirs to an interpretation of Romans 13 that went back to the Reformation. Reformation theologians often used Romans 13 to bolster support for law and order, most notoriously when Martin Luther justified the violent suppression of a peasant uprising. But in a long exposition of the passage, John Calvin argued that all the powers that be were ordained by God, including not just the king but also all the lesser magistrates. Those lower ranked officials were expected to resist kings “when they tyrannise and insult over the humbler of the people,” and Calvin listed the people in the Bible who had resisted “slavish obedience to the depraved wishes” of lawfully constituted authority. Where Loyalists invoked the law-and-order interpretation of Romans 13, Patriot clergy argued that only just authorities were to be obeyed.

Once those supporters of the Revolution had to turn to governance, though, the law-and-order version of Romans 13 had more appeal. Massachusetts pastor Zabdiel Adams, citing another passage of Scripture to explain why Romans 13 supported rule by Congress, argued that God was a “God of order and not of confusion.” The text sat uneasily with the American impulse for democracy, however, and Americans cited the verse on both sides of many issues, especially as evangelicals increasingly managed to bring their moral concerns about Sabbath-keeping, drinking, gambling, and slavery into the public sphere.

Romans 13 erupted into the public debate in 1850 with the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act. That law gave teeth to a provision in the Constitution by requiring that state officials and even “all good citizens” aid in returning people who had escaped slavery to bondage. Defenders of the slave system dismissed the abolitionist argument that the act was “opposed to the Divine Law.” The Richmond Daily Dispatch was sure that there were “hundreds” of “passages from Scripture proving the slavery has the divine sanction,” among them Romans 13, which demanded cooperation with the return of fugitive slaves. A North Carolina paper railed that “these Christians in the free States set up their judgments against that of the Almighty, and blindly strike against all law, order, and right!” It bluntly called down Paul’s threat of “damnation” as “Divine vengeance upon their evil deeds.”

There were at least three other commonly held interpretations of Romans 13 as it related to the Fugitive Slave Act. Illinois minister Asa Donaldson took the quiescent view that “the scriptures everywhere treat the worst of human governments as better than anarchy,” and that because no one was forced to participate in “buying and selling slaves” everyone was bound to avoid “all acts of hostility against the laws of the land, however corrupt.” Many anti-slavery activists, by contrast, held that the moral law God had ordained took precedence over the government leaders he had ordained. So without threatening to dissolve the union, they refused to participate in bringing “the fugitive slave back to the master and the bondage” and were willing to “suffer the penalty” for civil disobedience rather than “commit the crime” of helping to re-enslave a person. One Vermont author, for example, argued that the United States, “with its enslavement of the Africans and its extermination of the Indians,” stood outside Paul’s command to obedience. But the most radical of abolitionists came to believe that the Bible did justify slavery, and rejected the Bible on precisely those grounds.

Black Christians were accustomed to hearing from white slaveholders a bowlderized gospel that emphasized texts like Romans 13 and Colossians 3 (“Servants, obey in all things your masters.”) But their own readings of the Bible emphasized the book's themes of deliverance from bondage. The Exodus narrative was a more central text than Romans 13. The black abolitionist David Walker compared the United States to slaveholding Egypt and enslaved African Americans to the children of Israel. “All persons who are acquainted with history, and particularly the Bible,” he wrote, and “who can dispense with prejudice long enough to admit that we are men ... and believe that we feel for our fathers, mothers, wives and children, as well as the whites do for theirs” could see plainly that the Bible was on the side of the oppressed and not the oppressor. As Maria Stewart put it in an 1831 address suffused with scripture, “You may kill, tyrannize, and oppress as much as you choose, until our cry shall come up before the throne of God.”

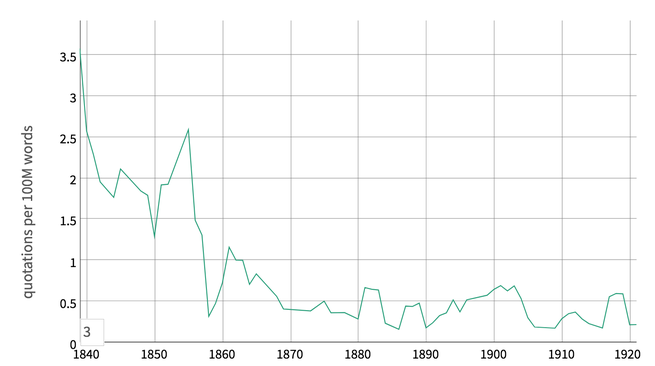

The debates in the 1850s over whether Romans 13 required obedience or resistance to the Fugitive Slave Act, and more broadly over whether the Bible supported enslavement or abolition, fractured the Bible’s authority in the public sphere. Americans’ allegiance to Romans 13 in a democratic society grew even more tenuous. While Southern Christians did keep defending slavery from the Bible even after the Civil War was over, slaveholders could no longer claim that they were “the powers that be.” The text never entered the public discourse again the way that it had in the 1850s.

Where does Jeff Sessions fit in this brief history of Romans 13? Sessions, like so many other Americans throughout history, thinks he has the Bible on his side. The verses Sessions chose to cite, and the interpretation that he has given them, is part of the broader Trump administration strategy of playing to the fears and identities of American evangelicals, who have been bringing Romans 13 back into public discourse since the rise of law-and-order politics and the Christian Right. But the Bible is a text less often read than read into. As many of his “church friends” persist in pointing out, Sessions did not cite the verse later in Romans 13 where Paul writes that God’s laws “are summed up in this word, ‘Love your neighbor as yourself,’” with the word “neighbor” echoing both parable of the Good Samaritan and the countless verses in the Law and the Prophets on treating the stranger and the immigrant with mercy. Sessions may claim the Bible’s contested authority, but what the attorney general actually has on his side is the thread of American history that justifies oppression and domination in the name of law and order.