Over the past several weeks, we’ve reviewed the history of Kaiser-Frazer cars. Today, we’ll look at the larger-than-life story of the founder of Kaiser-Frazer: Henry John Kaiser.

The Kaisers père et fils in the 1951 debut of Kaiser-Frazer cars in New York. Left to right: Edgar, Henry J. and Henry, Junior.

Jim Donnelley’s article about Henry J. Kaiser in the March, 2015 Hemmings says this:

Like many monumentally successful entrepreneurs, Kaiser was able to dream in three dimensions, only the scale of his deeds were vastly larger than most of his peers’. We know Kaiser for his heritage in the auto industry, but decades after his death, the truth is that chapter of his life almost counts as a footnote. Kaiser was a patriot. He tamed the Colorado River. He laid down roads in areas thought impassable. He helped to win World War II by building ships in a way that most naysayers flatly thought to be impossible. The fact that Kaiser built cars pales before the fact that he did so much to build America, at least the great, yawning, wild expanses of the West. That was all before he built ships. And cars. And invented the modern HMO. All things that his detractors said were flatly impossible.

Kaiser was born in 1882 in Sprout Brook, New York, a tiny village in the Mohawk River valley west of Canajoharie. Kaiser earned his entrepreneurial chops through pure experience, not classroom attendance. His first job was handling deliveries for a local dry goods retailer. That didn’t last. Kaiser wanted to be his own boss. He allowed himself the indulgence of photography as a hobby, and by age 16, he’d opened a camera shop in the booming tourist region that included Lake Placid. On his shingle, Kaiser called himself “The Man with the Smile.” The strategy worked. He opened a string of shops dotting the Atlantic seaboard as far south as Florida.

Continuing from Donnelly’s article in Hemmings:

His prospective father-in-law, however, pooh-poohed photo sales as inconsequential, and challenged Kaiser to improve himself. Kaiser left New York and traveled all the way to Spokane, Washington, where he swiftly earned a reputation as a master hardware salesman. That brought him to the attention of a succession of major construction companies that were undertaking big road projects in the western United States and across Canada. The contacts he made helped convince a Toronto banker to loan him $25,000, despite Kaiser’s having no equipment, employees or customers. But he got the loan and was in the construction business for himself.

World War I was beginning, and Kaiser was about to rapidly ascend into the pantheon of global business superstardom. Moving to Oakland, California, and realizing that the automobile was about to come into very wide usage, Kaiser tackled major highway construction projects, totaling thousands of miles, in California, Canada and even Cuba. He quickly gained a reputation for doing quality work ahead of deadline and under budget. It’s difficult to describe from afar, but Kaiser learned fast when it came to the organizational side of complex, high-dollar projects, a talent that would serve him extremely well throughout his life.

It was inevitable that Kaiser would come to Washington, D.C.’s, attention at some point. He had already expanded into dam construction by the 1920s, building one across the Feather River in California, and then erecting levees along the Mississippi River. By the late 1920s, with the Depression looming, planners in Washington were taking a serious look at the potential for constructing a massive hydroelectric dam across the Colorado River, to tame its uncontrolled flooding. The site was Black Canyon in Arizona. It’s a struggle to grasp the sheer scale of this plan: Building the Boulder Dam, as it was originally known, would require 4.5 million cubic yards of concrete, more than all U.S. Bureau of Reclamation projects combined in history up to that point. The only intelligent way to proceed was through a consortium of major construction businesses, thereby spreading not only the work, but also the considerable risk.

Kaiser emerged as first among equals in the group that won the contracts in 1931, which became known as the Six Companies. The sheer scope of the dam project required the Six Companies to build a 19-mile railroad to the dam site (which, after the dam was completed, ended up submerged beneath Lake Mead), and an electrical line run in from California to power a huge refrigeration plant, where ice to properly cure the tons of poured concrete was processed. To speed excavation, a Kaiser manager rigged up a truck with a network of drill bits so blasting holes could be drilled as a group, not one at a time. The hot, dangerous work proceeded at a marked clip, until today’s Hoover Dam was finished in 1935, under budget and two years ahead of schedule. Kaiser was instantly the third-most-recognizable person in the United States, according to polls, trailing only Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Henry Ford.

The Six Companies went on to other dam and aqueduct projects as World War II approached. With the growing likelihood of a two-front war in Europe and the Pacific, military planners took worrisome note that much of the nation’s shipbuilding capacity had been idled by the Depression, amid a glut of older ships from the previous conflict. Once the war began, that existing tonnage was being sunk virtually at will by packs of German U-boats. The generally accepted story today is that somebody in the Pentagon casually asked Kaiser if he’d ever considered building ships. It was an outlandish proposition. So, of course, Kaiser agreed.

Kaiser deserves credit equal to anyone with stars on their shoulders when it comes to winning World War II for the Allies. He started out in Portland, Oregon, before setting up a massive network of shipyards in Richmond, California. The enormous yard was the first “integrated” fabrication facility on the West Coast, as Kaiser built his own steel mill there, taking a page from Henry Ford’s playbook when he built the sprawling River Rouge complex. Though he admitted never having seen a ship launched previously, Kaiser did the impossible, building Liberty and Victory ships on an assembly line basis, something never previously attempted. To speed construction, Kaiser specified that the ships be welded together from steel sheet rather than using time-consuming hot rivets. To the astonishment of many, it worked. Kaiser employees (including hundreds of women) sent 1,490 ships down the Richmond ways through the end of the war, providing crucial ocean transport for war matériel as the invasion of Europe drew closer. In another advance, their hulls served as the basis for some of the U.S. Navy’s first light aircraft carriers.

By all indications, Kaiser’s commoner background made it easy for him to bond with laborers of all races and both genders. It likely also piqued his interest in a new industry to conquer, knowing that demand for cars would explode after World War II ended. This, of course, became Kaiser-Frazer, formed in 1945 after Kaiser had not-too-subtly teased the public about getting into the car business. The actual partnership between the men was unconventional, Kaiser being the do-it-all business mogul and Joseph Frazer, a former protégé of Walter P. Chrysler who had run Willys-Overland before buying a controlling interested in the staggering brand that was Graham-Paige, which gave the new firm its first dedicated assembly facility in Detroit. That changed soon as Kaiser took over the gigantic assembly plant at Willow Run, Michigan, where Henry Ford had been building B-24 Liberator bombers during the war. The excitement was palpable; a showing of prototypes caused Kaiser-Frazer stock to zoom to $24 a share, its all-time high, before a single production car was built.

That Kaiser-Frazer lasted as long as it did was both predictable and miraculous. The manufacturer had its share of cars that were at once conservative and innovative. Think the Vagabond sedan, which could be converted into a camper, and the compact Henry J. The startup issues that the company faced, attempting to introduce highly complicated consumer products in an overheated market, were monumental: Expensive machine tools had to be located and installed on short notice, and Kaiser-Frazer coped with chronic steel shortages in its early years. Still, the first cars arrived in 1947 to positive reviews.

There were changes. Joseph Frazer left the company in 1953, the same year that the now-redubbed Kaiser Motors acquired Jeep from the remnants of Willys-Overland. A stock-offering deal imploded into six years of costly litigation. Significantly newer model cars were late to come to market, thus Kaiser’s dealer network began to fracture. By 1949, the firm was claiming only 1.5 percent of the new-car market. Even the new Henry J, introduced in 1951, saw its sales tumble by more than 75 percent in a single year. Despite the merger with Jeep and Willys-Overland, losses mounted. The suspension of domestic auto production that followed was inevitable.

Kaiser did continue to build his cars successfully for some time thereafter in venues that ranged from Argentina and Brazil to Israel. The firm kept manufacturing Jeeps as Kaiser, before his death in 1967, contemplated leaving the auto business entirely. The deal that sold Jeep to American Motors was consummated in 1970. In addition to his civil engineering triumphs, Kaiser’s greatest legacy is Kaiser Permanente, the health-care consortium that he founded for his workers in 1945. It grew by the 21st century to become the largest managed-care provider in the United States.

At its height, Kaiser’s industrial empire counted shipyards, steel mills, aluminum mills and concrete plants in its possession – not counting the auto operations.

Henry J. Kaiser was thinking about building cars earlier than most people realize. Enter Buckminster Fuller and the Dymaxion.

Dymaxion.

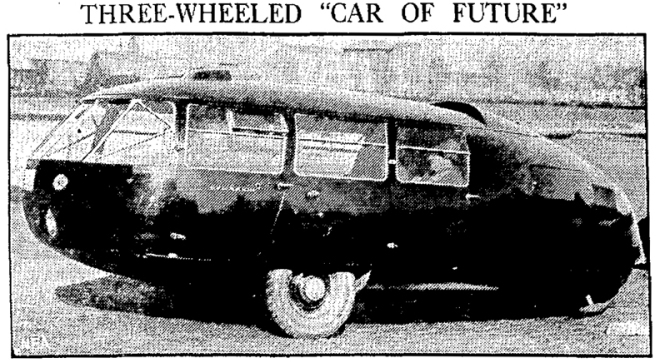

The very word screams “futuristic design,” and rightly so. It was industrial designer R. Buckminster “Bucky” Fuller’s term for his exotic road vehicle, so unusual it hardly seems fair to call it a “car.”

Dymaxion, a term Fuller used for describing his geodesic domes as well, was shorthand for Dynamic Maximum Tension. It was aerodynamically shaped like a zeppelin, with a strong and lightweight trussed frame. It had three wheels, two in the front and one in the back. The full-blown version would be nearly 20 feet long, fuel-efficient, and designed to carry up to 11 people. In partnership with design polymath Starling Burgess, Fuller produced a working prototype in their Bridgeport, Connecticut workshop and debuted it at the Chicago World’s Fair (formally known as the “A Century of Progress International Exposition”) in 1933-1934. National columnist Howard Vincent O’Brien described it on August 15, 1934:

[The Dymaxion car] is on exhibit…in the Crystal House, and is well worth a look if you are interested in knowing what sort of vehicle may soon be taking you about.

It’s a three-wheeled affair, driven from the front wheels, and with the engine in the rear. It turns on its own base, and, using a standard Ford engine as a power plant, it will go – says Mr. Fuller – 125 miles an hour, doing 30 miles to the gallon of gasoline.

I haven’t ridden in it yet, but those who have say it floats like an airplane.

The Dymaxion vehicle never went into production. An accident in October, 1933 killed the test driver and injured several bystander investors, which doomed prospects for further commercial development. The design occupies the fringe area of “good ideas that weren’t practical.”

But visionary industrialist Henry J. Kaiser gave it a shot.

Kaiser made history when he entered the automobile market in 1945, applying his industrial mass production skills to a postwar world hungry for vehicles. He partnered with veteran automobile executive Joseph Frazer to establish the new Kaiser-Frazer Corporation, from the remnants of Graham-Paige, of which Frazer had been president. Kaiser’s name would grace the affordable and practical end of the line, and Frazer would be the nameplate on the upscale side of the lot.

It’s not commonly known that years earlier, at the end of 1942, Henry J. Kaiser paid Bucky Fuller to engineer and produce a ¼ scale model Dymaxion, to be completed in early 1943. At that time Henry Kaiser was committed to various wartime vehicle projects under federal support, including building cargo ships and “baby flat top” aircraft carriers, prototyping lightweight jeeps, and even experimenting with giant flying wings. So it should come as no surprise that, with the support of the Board of Economic Warfare (on which Fuller served as staffmember), he explored the advantages of Fuller’s Dymaxion.

According to Fuller scholar J. Baldwin, the updated design would include several of these features:

Powered by three separate air-cooled “outboard” type (opposed cylinder) engines, each coupled to its own wheel by a variable fluid drive. Each of the engine-drivewheel assemblies was detachable. The engines themselves were run always at the same speed; the speed of the car was controlled by varying the quantity of fluid in the coupling;

Low-horsepower engines – 15 to 25 hp, cut down to one engine at cruising speed, for 40-50 mpg; Steered at cruising speeds by the front wheels, rear-wheel steering was used only as an auxiliary for tight turns, or to move sideways; High speed stability enhanced by extending the rear wheel on a boom to lengthen the wheelbase.

Alas, the prototype results were not impressive.

In August, 1946, author Lester Velie wrote this in a three-part series on Henry J. Kaiser for Collier’s magazine:

Kaiser had dabbled with cars since 1942. In that year he commissioned Buckminster Fuller, the industrial designer, to design a car. Fuller came up with what he called a dymaxion car, a three-wheel job, with a motor that could be hitched to front or rear, or to any of the three wheels. He made a mock-up of the car’s tear-drop body in plywood. This and engineering drawings he submitted to Kaiser, expecting Kaiser to commission him to do the further necessary engineering toward a completed prototype.

Kaiser shipped the plywood mock-up of the Dymaxion car to his cement plant at Permanente, Calif. There, without waiting for such refinements as a specially designed motor, he slung a secondhand Willys-Knight engine on the three-wheel job and started riding.

The Dymaxion turned over.

Undaunted, Kaiser brushed himself off and went to New York where he announced belligerently before a National Association of Manufacturers audience that if the automobile industry lacked the courage to plan postwar automobiles now, he would have to do it himself.

Despite Henry Kaiser’s enthusiastic and reckless test drive, the Dymaxion’s road stability was not an insurmountable design flaw (it did have a few, including poor rear visibility and an unfortunate tendency for the rear to lift off the ground at speed). But the project ended there, and it never saw production.

–00OO00–

Kaiser Aluminum

In 1957 Henry J. Kaiser and Bucky Fuller would again collaborate on another project, the commercialization of aluminum geodesic domes using aluminum from Kaiser’s aluminum mills.

Despite having exited the passenger car business (while retaining the Jeep) in the U.S., Kaiser envisioned all-aluminum cars using (naturally enough) aluminum produced in his aluminum mills. Kaiser commissioned Frank Hershey to draft designs for an all-aluminum Kaiser car for 1958. The car never got any further than Hershey’s drawings, but the project showed that Henry was still interested in the car business.

–00OO00–

A Fringe Benefit for Kaiser Permanente Doctors

A fringe benefit for Doctors working in the Kaiser Permanente Health System was they were given Kaiser cars to drive. In the days before 1952, doctors used the company car to make house calls ($5 per visit). The physicians had a choice of vehicles; most chose one of the sedans. But Ed Schoen, a pediatrician who joined KP in 1954, saw the Kaiser-Darrin as an apt ride for a bachelor relocating from Boston to the San Francisco Bay Area.

The Kaiser-Darrin on a postage stamp. Painted by Art Fitzpatrick who had worked for Dutch Darrin before World War II and later became famous for his part of the illustrations he and Van Kaufman painted for Pontiac.

When the auto manufacturing venture in the U.S. ended in 1955, Kaiser offered to sell the cars to the doctors at bargain prices. The Darrin had originally retailed for $3,600. Schoen got his with 6,000 miles on it for $900. He would drive the unusual sports car exclusively for the next eight years, and he got a lot of attention driving around town. “People used to follow me home from work and ask me, ‘What is it?’” Schoen related. And as a bachelor, Schoen found that girls fancied a ride in the Darrin.

After meeting his wife, Fritzi, who came to the U.S. from Austria in 1958, Schoen took her many places in his cream-colored convertible. “I courted her in that car. . . She liked it,” he said. Ed and Fritzi married in 1960, and it wasn’t long before the Darrin was no longer practical. A daughter, Melissa, was born in 1963, and son Eric came along in 1968.

Kaiser-Permanente physician Ed Schoen choose this Kaiser-Darrin as his company car rather than one of the Kaiser sedans. He owned the car for almost 50 years.

But Schoen kept the car and drove it to work for many years. In recent years, he had it restored and preserved it in his garage. He entered it in car shows and won a couple of prizes competing with Ford T-birds and Chevy Corvettes. He also loaned the car for the 50th anniversary of Kaiser Permanente Vallejo and for display during another KP event in Oakland at Mosswood Park. The Darrin was never neglected: Schoen took it out for a spin almost every weekend.

After owning the car for almost 50 years, Schoen donated his Darrin to the Oakland Museum in 2004 for the Henry J. Kaiser “Think Big” exhibit. The Darrin was shown along with a 1953 Henry J Corsair Sedan in the ambitious exhibit that covered Kaiser’s amazing life as a 20th century industrialist and co-founder with Sidney R. Garfield, MD, of the Kaiser Permanente health plan. Today, Schoen’s Darrin is in storage awaiting a new venue.

–00OO00–

Kaiser Loved Boating

Kaiser loved to pilot speedboats. He maintained a summer home at Lake Placid,N. Y., where he pursued racing with his neighbor and friend band leader Guy Lombardo. In 1949 the Ticonderoga Sentinel noted:

“For the second successive week end, Henry J. Kaiser has visited Lake Placid to check on the progress of his two big speed boats. Guy Lombardo also appeared here Saturday to try out the massive 32-foot Aluminum First, with which he will try to break the world’s mile straightaway record in the time trials.”

That didn’t happen, but in 1971 the Lake Placid Sports Council mounted a plaque honoring their local heroes.

The Kaisers would not achieve racing victory until 1954, when the three-point hydroplane Scooter (U-12) powered by a 1750 horsepower V-12 Allison engine driven by Kaiser Industries welder Jack Regas won the Mapes Trophy unlimited class at Lake Tahoe. She ran second, first, and second and posted the fastest lap at 88.748 miles per hour. Henry immediately retired the boat and built a second, the Scooter Too with a 3,420 cubic inch 24-cylinder Allison engine, producing a staggering estimated 4,000 horsepower – but she never won a race.

Above: Henry J. in 1939 piloting the Hornet Gar Wood Speed Boat. Below: the Hornet

Things turned around in 1956. Edgar Kaiser’s unlimited-class three-point racing hydroplane Hawaii Kai III (U-8, named after Henry J. Kaiser’s Waikiki Beach hotel) won the first of six consecutive races, the William A. Rogers Memorial Cup trophy in Washington, D.C.

Above: Henry J. piloting his race boat Fond du Lac on the Potomac River.

Below: Henry J., age 73, in 1955 piloting Scooter too

o

o

She was powered by a V-12 Rolls-Royce Merlin engine. The following year she won the national championship and set the water speed record at the official American Powerboat Association runs in Seattle, Washington – 195.329 miles an hour, a bar that would stand for five years.

As with most of his goals, Henry J. Kaiser achieved what he sought, and he eventually retired from the racing circuit. His last boating venture was to build six massive touring catamarans in Hawaii, all named after his new wife, Alyce.

Alyce Kaiser (center left, wearing dress) at the Kaiser home in Lafayette, California with nursing students from the Kaiser Foundation School of Nursing.

The Kaisers had a retreat at Lake Tahoe. On July 3, 1951, at 69 years of age, Henry J. Kaiser sped off in a speedboat to rescue his wife Alyce “Ale” Kaiser and founding Permanente physicians Dr. Sidney Garfield and Dr. Cecil Cutting when their catamaran capsized in the frigid waters there. (Local note for San Francisco Bay Area residents: the original Kaiser Clinic was located at 23rd Street and what is now called Cutting Boulevard in Richmond. The street was re-named for this K-P founding physician.)

Above: 69 year-old Henry J. rescues his bride.

Below: “Ale Kai” the catamaran named after Alyce Kaiser

–00OO00–

Kaiser Cement

Henry J. Kaiser’s Permanente Cement works had just begun operations in 1939 when he learned that the U.S. Navy wanted to improve on deliveries of cement to Hawaii.

Kaiser claimed he could cut loading and unloading times by as much as 80 percent by pumping bulk, dry cement from ship holds into storage silos in Honolulu. Cynics said the cement would be ruined, but Kaiser guaranteed the product “…from our San José plant to the wheelbarrow in Hawaii.”

In October 1940, Kaiser purchased an aging freighter (the Ancon) from the Panama Canal Company and converted it to a bulk cement carrier. The ship went into service as the Permanente in March 1941 under contract with the U.S. Navy.

The Permanente was moored at Pearl Harbor when it was bombed by the Japanese on December 7, 1941. The ship was not damaged and had already offloaded its holds when the attack came. Within a few days the silos holding the offloaded cement were emptied for the emergency rebuild of the harbor.

By 1945 there were newer, faster, surplus freighters available, and the old Permanente was scrapped.

Two years later the Permanente Cement Company purchased a Victory-class cargo ship that had entered service in 1944, the Silverbow Victory. When this ship was refitted to carry cement, she was given the name, Permanente Silverbow. She bore cement to the isles until Kaiser built a cement plant on Oahu in the 1950s.

Permanente Silverbow sailing under the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge

–00OO00–

Henry’s “Retirement” In Hawaii

Henry Kaiser officially “retired” in the mid-fifties, relocating to Hawaii with Alyce. While Henry Kaiser stumbled in his attempt to conquer the auto industry, it was not his Waterloo, nor was it even his final venture. Before his death in 1967 at age 84, Kaiser went on to build a new empire in Hawaii, including the elaborate Hawaiian Village hotel complex in Waikiki (now owned by Hilton) and Honolulu’s Hawaii Kai residential community. Kaiser’s Hawaiian home and properties were often liberally decorated in bright pink — Ale Kaiser’s favorite color. Son Edgar Kaiser remained the chairman of Kaiser Industries until it was broken up in 1977, four years before Edgar’s own death.

Henry Kaiser, Jr. was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 1944 and died in 1961 at age 44 despite his father’s best efforts to find a cure.

Henry J. Kaiser created an empire worth tens of billions of dollars and earned a personal fortune of $2.5 billion. Yet he is almost forgotten today. On his death, he divided his fortune between his second wife, Ale, and the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, which was created to support the Kaiser medical program. His son, Edgar, received nothing because he was “otherwise cared for.”

Edgar replaced his father as chairman of the various Kaiser companies. But his personal investments in these companies was small, which may be why he was unable to keep the companies going. Edgar probably had a net worth of about $50 million, which is insignificant compared with Henry’s worth. It seems that if Edgar had inherited some portion of his father’s fortune, he might have been better equipped to hold his father’s empire together longer.

Neither Ale nor the Foundation had any particular interest in the future of Hawaii, the West Coast, or Kaiser Industries. After Kaiser’s funeral, Ale returned to Hawaii for only two very brief visits. Nor did she spend much time in California, instead moving to Greece. She sold all of the properties she shared with Henry. Given the swiftness with which Kaiser married Alyce after the death of his first wife and the way she left Hawaii and California for Greece suggests she made have had a vein of gold digging in her, but that is purely speculation on my part as I haven’t read anywhere that Alyce Chester Kaiser was, in fact, in it only for the money. The Foundation no doubt wanted to diversify its portfolio and also sold its interest in Kaiser Industries.

When Henry Ford died, control of his company was firmly held by his children and grandchildren. If Henry Kaiser had left a similar arrangement, Kaiser Industries might still exist today. Instead, lacking the strong rudder of an owner-entrepreneur, the companies faded away.

Kaiser Industries sold Willys Motors to American Motors (AMC) for about $70 million in 1970. AMC successfully revived the Jeep brand, showing what Kaiser could have done if it had taken the time to understand the auto industry a little better. In 1987, Chrysler bought AMC, mainly to get the Jeep brand, for $1.1 billion, nearly six times (after adjusting for inflation) what AMC paid for Jeep. In recent years, the Italian car maker FIAT merged with Chrysler – mainly to get Jeep, which is the largest part of the company today.

Kaiser Steel was sold off, plundered by corporate raiders, and went bankrupt in 1987. The site of the Kaiser Fontana steel mill is now an auto race track. Kaiser Aluminum still exists, though as a shadow of its former self, as does a company called Kaiser Engineering. Kaiser Engineering is headquartered in Emeryville, California where Kaiser engineers created the K-85 prototype car before Kaiser teamed up with Joe Frazer to form Kaiser-Frazer at the close of World War II. The Kaiser cement operations were sold, their distinctive pink cement trucks (Ale’s favorite color) re-painted. No member of the Kaiser family has an interest or involvement in any of these companies.

The Kaiser Permanente health system still exists with facilities in California, Colorado, DC, Georgia, Hawaii, Maryland, Ohio, Oregon, Virginia, and Washington State. Kaiser is the model for other HMOs all over the world, especially non-profit HMOs. Most people think this is Henry J.’s biggest legacy and memorial. Henry J. himself said that his HMO would outlast everything else he did and would prove to be his greatest achievement.

Mark Foster’s 1989 biography of Henry Kaiser uses terms like “can-do capitalist” and “frontier entrepreneur” to describe his subject. This is the conventional view.

An alternative view is presented by Stephen Adams, whose book, Mr. Kaiser Goes to Washington, calls Kaiser a “government entrepreneur.” The implication is that Kaiser used his lobbying skills to become an insider able to gain favors from government not available to more traditional entrepreneurs. The interpretation of one Amazon reviewer is that Adams’ book “exposes Kaiser as a sociopath, war profiteer, and con-man.”

That’s an extreme reading of Adams’ thesis, but even Adams’ more gentle view is unfair to Kaiser. Except during the war, Kaiser only once asked the government for any projects or favors other than the ordinary permits that anyone would need. Most of Kaiser’s contracts before the war were with the government, but they were all initiated by the government; Kaiser was merely a bidder. During the war Kaiser made a variety of suggestions, such as the cargo planes and escort carriers, but it was everyone’s patriotic duty to do what the could to win the war faster.

After the war, Kaiser benefitted from the government’s below-cost disposal of aluminum plants. But, again, it was the government that initiated such disposals, and in any case, no one else (except perhaps Alcoa, which was forbidden to bid) was willing to bid on the plants that Kaiser ended up buying.

The only special favor Kaiser ever requested was for a discount on the loan the federal government made for his Fontana steel mill. In Kaiser’s eyes, this was only fair since the government sold its Geneva, Utah steel mill to U.S. Steel for 20 percent of its value. In any case, Kaiser didn’t get the discount, suggesting he really didn’t have much influence over the government.

Entrepreneurs want to build businesses. In an environment where government is a major customer, entrepreneurs will do business with the government. If Kaiser’s business differed from, say, nineteenth century entrepreneurs, it was because the government was different, not because he was a different kind of entrepreneur.

Yet in other important respects, Kaiser was different from the stereotypical capitalist. He had a deep sense of honor and fairness in dealings with other people. When forming partnerships with others, his lawyers often suggested that he should get 51 percent to his partner’s 49 percent. “You can’t have a partnership based on a 51-49 relationship,” he said, and made them 50-50.

When his auto company was failing, one of his associates noticed him brooding and asked why. “I received a letter from a railroad conductor telling me he had invested his retirement savings into Kaiser Motors,” he said. “He didn’t ask for anything, just expressed confidence that I would make it a success. I can’t let people like that down.” So he, in essence, gave up close to $200 million of his own shares in Kaiser Aluminum and other companies to repay Kaiser Motors’ debts and make its shareholders whole. Contrast this with Studebaker. When Studebaker shuttered its auto operations in South Bend, Indiana, the company did not fund its pension liabilities, costing Studebaker employees and retirees their retirements.

Kaiser could be generous with his partners, stockholders, and employees because he was an owner, not a manager like the people running, for example, other steel companies. As an owner, he could give up value to partners and employees, while a business manager obligated to maximize shareholder value could not. Nor could a manager legally take value from one company and give it to the stockholders in another, as Kaiser did for Kaiser Motors (though it must be emphasized that the value he took came from his own shares, not other Kaiser Industry shareholders).

Still, just because he could be generous doesn’t insure that he would be generous. Kaiser may have been altruistic, but he may have also realized that treating people with fairness was an important way to motivate them. Perhaps not every entrepreneur understands this, but it is likely that the most successful ones do.

Kaiser wasn’t a saint. A workaholic, he expected his executives to be workaholics as well. He often berated them for things that were beyond their control, sometimes “firing” (and usually later rehiring) them over insignificant issues. He couldn’t work with his partner in Kaiser-Fraser Motors, Joseph Fraser, and ended up having to buy him out.

Still, Kaiser’s generosity and sense of fairness greatly outweighed these defects. Kaiser will long be remembered through his health care system. He should be equally remembered as one of the greatest entrepreneurs of the twentieth century.

The logo on the Henry J car was modeled after Henry J. Kaiser’s own signature

Quite a history. I was proud to work for Kaiser-Jeep Corp as Regional Sales Manager, New Haven District, Had a few Kaiser products, Jeeps, pickup, wagons, Kaiser car and a Frazer Manhattan.

LikeLike

THANKS. I never knew Kaiser was into so much. But somebody dropped their candy when the Hershey car was not produced that is for sure! Way ahead of it’s time….!

LikeLike

Paul, another well researched and very interesting piece. Thanks again, Gordon

LikeLike