ArtSeen

JOHN GRAHAM

Richard York Gallery | 2002

I once had a discussion with an art historian friend who insisted that the uniqueness of John Graham is almost identical to that of Emile Bernard. My friend really meant that both were lesser painters, but their ideas and intelligence had great significance in broadening new possibilities for their contemporaries. In the case of Bernard, it would be for Cézanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh and Seurat. Within the circle of artists who were under Graham’s influence, the list is just as impressive: Gorky, de Kooning, Smith and Pollock, (it was Pollock who wrote a letter to Graham after reading his article, “Primitive Art and Picasso,” published in Magazine of Art, 1939—a letter which initiated a very special friendship between them). Although the comparison between Bernard and Graham sounded good to me in theory, but in point of fact, I think perhaps Graham wasn’t as intellectually consistent or logical as Bernard, though he was a far more adventurous theoretician and a better painter than Bernard ever was.

John Graham was born Ivan Gratianovich Dombrowsky in Warsaw to a Polish noble family. After serving as the Czar’s cavalry officer during WWI, he found his way to Paris and eventually to New York in 1920. Graham attended the Art Student’s League. Among his fellow students were Barnett Newman, Adolph Gottlieb and Alexander Calder. With a charismatic personality, he stood out as a witty and acerbic teller of tales and adventure stories. Ultimately, Graham was a great advocate of Modern Art, especially Cubism.

For anyone who has read Graham’s System and Dialectics of Art, the small exhibition at the Richard York Gallery would have been a great treat. Those who are not at all familiar with his work would have found it more than interesting. And most of us who vaguely know that Graham was a great connoisseur of art, who also had an enormous impact on the New York School, were reminded that he was one of the most fascinating and complicated artist of his time.

Despite the lack of a few major paintings, which happily was made up for by the first viewing of “Poussin M’Instruit,” a painting which hadn’t been shown for over thirty years, there was enough work in the show to constitute a comprehensive survey of Graham’s evolution. He painted still-life, landscape, equestrian themes and eventually his landmark portraits of cross-eyed women. In fact, not unlike his fellow ‘migr,’ Arshile Gorky, Graham took the notion of an artist’s development very seriously. According to Graham, there are three phases of an artist’s life: apprenticeship to the master, a period of uncertainty or intense search through confusion, and finally mature resolution.

From the beginning, one clearly sees his painting as a mixture of Matisse, Derain and Braque. A notable transition is evident in the two paintings “Coffee Cup” (1928-1929) and “Abstract Sill-Life” (1930). In the former picture, the configuration with the two eggs and a coffee cup sitting on a plate occupies the whole canvas, whereas in the latter, the same egg form is repeated, only in a much larger and more complex composition. Although the language of synthetic cubism is successfully employed, there is an unusual contrast between the monochromatic egg form, painted in a quasi-modeling manner, and all the brightly colored and silhouetted shapes. This strange pictorial tension is also apparent in de Kooning’s seated figures and abstract still-lives of the late 1930s.

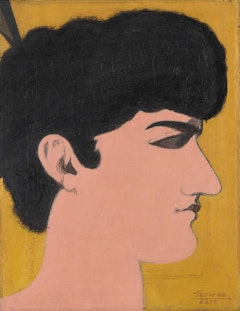

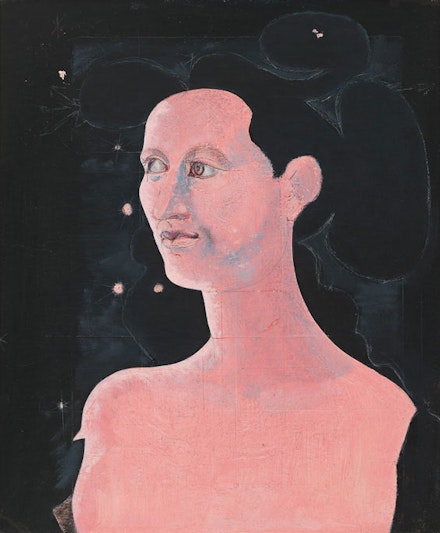

Later, in Graham’s legendary three-quarter profile, “Cross-Eyed Woman,” perhaps this time it is Graham who has taken some motifs from de Kooning. In “Poussin M’Instruit,” a double self-portrait, there is no doubt that such elements as the interplay of biomorphic shapes against the highly geometric structures in the background, and the pervading tone of the fleshy pink palette, is particularly reminiscent of de Kooning’s male or seated figure paintings of the 1940s. However, while de Kooning’s palimpsest of the figures often allude to sensuality and his love of the Pompeii murals, Graham, on the other hand, borrows freely from Raphael and Ingres and his portrayal of the figure is disturbing, quite the opposite of sensual. Graham’s portraits exist between the poetic ambivalence of eroticism and a sense of enigmatic mystery—two elements which derive from his personal life as well as his intense interest in esoteric philosophies, i.e.: mythology, occult literature, alchemy, Jungian psychology, and many forms of yoga and meditation.

Two other great pictures in the show were the oil paintings “Aurea Mediocritas” (1952) and the pencil drawing “Puisis in Inferno” (1958). Both typify the superficial appearance of calmness, the Ingres-like quality of classical balance in Graham’s form and design. In addition, they also reveal his obsession with the Golden Section, especially in the oil painting. One sees the square grid with perspective lines as well as all sorts of writing—Greek letters and astrological symbols—scratched mostly on her face. The work of this period, which lasted from the mid 1940s to the late 1950s, is his strongest. Here, Graham has achieved the most beautiful synthesis of past and present art in painting. Perhaps in none of his contemporaries’ work would we ever find an example where Leonardo, Raphael, Ingres and Picasso could coexist in a single visual language contained in one painting. At some point in the mid 1940s, Raphael took Picasso’s place as Graham’s fountainhead of art. As he turned against cubism and abstract art altogether, Graham pledged his struggle to deny his immediate past and to go further back to the Renaissance. As a result, his work remains a bizarre curiosity.

Overall, this small and delightful exhibition was a great effort to increase public awareness of Graham’s work. I am almost certain that in Graham’s resourceful and conceptual brilliance—which he couldn’t always transform into action—can be found a fertile ground for young figurative painters today. Ever since the 1987 exhibition at the Phillips Collection in Washington D.C., there has been a growing interest in Graham’s work. I wonder whether the Whitney Museum would ever consider giving a major retrospective to John Graham in the near future. That remains to be seen.