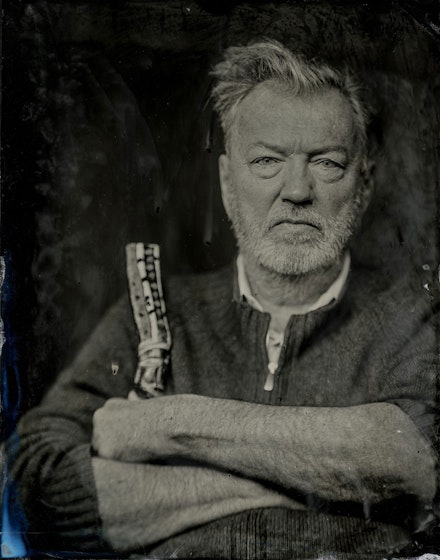

When Diego Cortez died on June 20, 2021, I felt the need to memorialize him in some way, because so much of what he did was ephemeral, although no less important for being so. Diego was a catalyst in the literal sense of the word: something that precipitates or facilitates a change. He touched and changed a great many lives, as the many contributors below attest. His 1981 New York/New Wave show at PS1 ranks with the Armory Show of 1913 as one of the most consequential art exhibitions of the 20th century. In the ensuing years he curated over 100 additional exhibitions.

Diego arrived in New York at the dawn of punk and he remained true to that sensibility all his life. The art world was his medium, first as a performance artist, and later as a writer and editor, a curator and gallerist, a music producer and promoter. In my mind Diego constituted a trio, along with his friends and sometimes rivals Edit DeAk and Rene Ricard: shockingly intelligent outcasts who dominated the New York art scene and nightlife of their era. Fearsome and outrageous, they simply saw and knew and understood more than anyone else. The seriousness with which they treated art I have not encountered since. It’s the reason one came to New York: smart people. Unlike so many of his peers on the scene, Diego was (usually) kind, encouraging, and approachable. His literary interests made him a great supporter of little-known writers, including Kathy Acker, Cookie Mueller, and Duncan Smith.

In later years his focus turned to music, photography, folk art, and so-called outsider art—in addition to his first loves of film, painting, sculpture, and conceptual art. Since the mid-’90s Diego led a peripatetic life, living in Puerto Rico, Brazil, Tokyo, New Orleans, a loft in Harlem, and an apartment in Brooklyn, before finally settling in North Carolina, where he ran a gallery (Partobject, in Carrboro) with his sister Kathy Hudson. I always liked how he did not tie himself down to New York and its culture.

In his final years Diego was an informal guest lecturer in graduate seminars at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He was a challenging and captivating speaker, and outspoken as ever. In his final class visit, half the students walked out on him and marched to the Chair's office to complain. The professor, his friend elin o’Hara slavick, who invited him, was removed from that seminar and subsequently resigned her position. Somehow I am heartened to think he ended his career the way it began: provocatively.

–Raymond Foye

Al Diáz

Remembering Diego

By 1978, when I was about 19, SoHo was in full swing commercial development. West Broadway, Prince, Spring, Broome, and Grand streets were now lined with galleries, boutiques, and restaurants. The streets running north and south, including Mercer, Greene, and Wooster, still showed signs of an earlier period, when light industry was the primary activity in the area. They were poorly lit and still paved with cobblestone. Aside from the Anthology Film Archives, the Wooster Group theater, and some lesser-known galleries, these streets remained less populated. Trucks, loading docks, shipping debris, and textile scraps were a common sight. The area was replete with luminaries of various social strata: musicians, artists, writers, actors, filmmakers who made up most of its inhabitants.

Then, SoHo had a sense of neighborhood with a host of familiar characters you’d regularly see at parties, clubs, openings, and other events. Downtown New York City was still affordable for young people and conducive to a Bohemian lifestyle. Being a restless young New Yorker without absolute direction or objective, I frequently roamed the streets in search of adventure, entertainment, and activity. I first met Diego Cortez on one of these jaunts. A few friends and I had set up a loading skid vertically on a wall of a building that probably now has a surveillance system to prevent the type of mischief we engaged in. We were using the skid as a practice target for hurling Chinese throwing daggers. The game had been on for a while when a tall, pleasant-faced young man wearing Ray-Bans stopped with his associate to watch us. The man had a Super 8 movie camera tucked under his arm.

“This would be great for my Elvis movie,” he said (as if we knew about his Elvis movie, which I later discovered was titled Grützi Elvis). “Do you guys mind if I shoot you throwing the knives?” he asked.

We all agreed to being filmed and continued our game, perhaps more fervently for his camera. After they had the footage they needed, the tall fellow introduced himself as Diego Cortez, and to show his gratitude, invited us to a party later that evening at a nearby loft. So, a few friends and I showed up to an address on the piece of torn off notebook paper. I remember being starstruck as we saw Brian Eno walk out of the building as we approaching.

Me, very excitedly: “Hey, you’re—”

Eno, as he skirted away half laughingly: “No, I’m not the guy…”

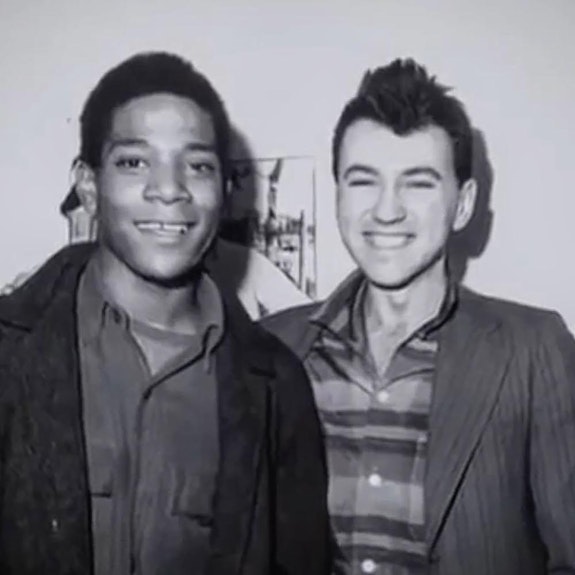

I remember staring as Eno faded away and thinking to myself, I wonder who this Diego guy is? After that night I started to notice Diego at clubs and parties, and stopped by his office once on Bleecker Street concerning an article in his publication. I would later learn of his association with Jean-Michel Basquiat and his involvement with the now-legendary New York/No Wave MoMA PS1 art show, when I played music with Elliot Sharp’s ISM. Although we never became super close friends, we certainly had quite a few friends in common and would remain in good standing for decades to come. I saw Diego alive for the last time in 2017 in London when Basquiat’s Boom For Real exhibition opened at the Barbican. He took a break from the video interview he was doing to say hello. Diego Cortez took with him a great deal of sought after, first-hand Downtown New York knowledge … history and lore that cannot be reclaimed.

Alanna Heiss

“Time to Go … (for Diego)”

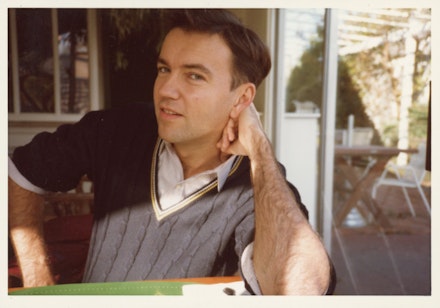

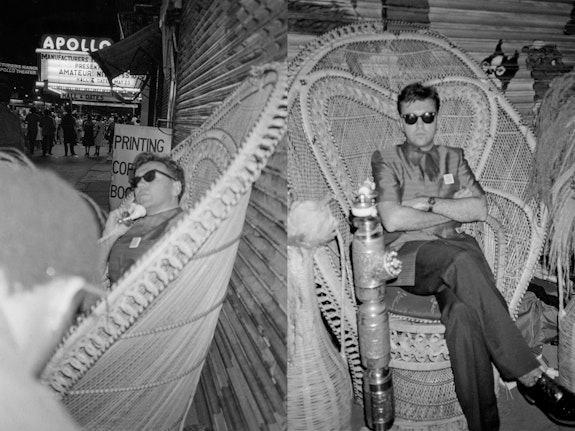

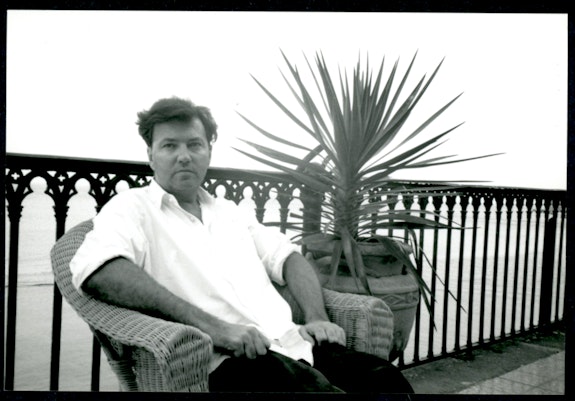

The young Diego bore a slight resemblance, more successfully at night, to Elvis Presley. The old Diego bore a passing resemblance to fat Elvis, although our Diego never reached the massive proportions of that great performer.

I met the young Diego in 1973 at the Clocktower, an alternative space that I founded and ran from 1972 until the building was sold to a developer in 2018. The asking price for the multilevel apartment located in the old Clocktower space designed by Stanford White, (the location of over 1000 shows over the last 50 years) was 36 million dollars. However, in the early years, our not-for-profit art space had a total annual program and staff budget of about 27,000. Diego was friendly (sleeping with) some members of the young and attractive Clocktower team and was frequently found hanging out in our offices and the many disheveled rooms used as studios and production space for artists of that time. These artists included Vito Acconci, Lynda Benglis, Kenny Scharf and his gang. I was only three years older than Diego but was the designated grown-up in the space. It was clear to everyone that out of our little budget, Diego, who did nothing but talk on the phone to his friends and arrange for complimentary tickets to performances at hip bars, was not going to be paid. This certainly didn’t matter to Diego, who was already a superb hustler and a much sought-after presence at concerts and gatherings.

Diego’s relationship to concepts of necessary living costs were interestingly flexible and somewhat unusual. He expected to live rent free and to spend nothing on boring necessities such as a telephone, electricity, taxes, and food. However, entertainment, taxis, drugs, and booze were important. Years later, when Diego and I worked together, I spent many hours drafting and editing budgets for the NEA and the NYSCA for his projects which could represent expenses of this nature.

Naturally, Diego was a desired companion by many of the most adventurous artists, musicians, and photographers of the ’70s and ’80s. He was smart and a good critic, bold and energetic and completely committed. Most importantly, he was taking and making the same chances and choices that they were. And he was a lot of fun.

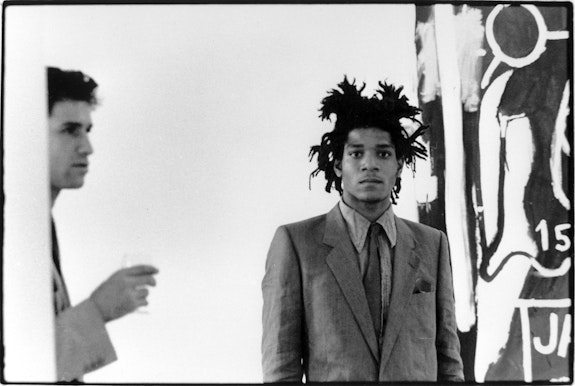

For me, Diego represented a trustworthy native guide to the artistic underworld which remained ultimately inaccessible to me, but acutely exciting and important to understand. When he proposed the New York/New Wave show to me for PS1 in 1981, I didn’t need my arm twisted. That exhibition, along with the opening Rooms exhibition, became the defining exhibitions of PS1’s early remarkable history, primarily because this massive show of over 500 artists (to which Diego continued to add, replace, remove, etc.) established the crucial relationship and crossover between music and art of that time.

Doing an exhibition with the young Diego was not for the faint-hearted. He was completely uninterested in the process of assembly, transport, shipping, insurance, and labels, which are the scaffolding of any large group show. He was a consummate liar, and frequently misrepresented crucial details that he either hoped would come true or didn’t care about. In this, he was more similar to the manager of a rock band (Diego successfully acted in this role several times) than the curator of an art exhibition. In years to come, Diego came to recognize that his efforts were best spent on artist projects and smaller shows concentrated on really good works by one artist. He was usually able to isolate key elements of the artists’ concerns and through his presentation ensure that the artistic impulse remained alive and throbbing. I considered him a non-conventional but inspired show organizer.

I never worked on another show with Diego. We kept up a relationship and when we spoke, I would casually suggest another adventure and he would usually update me and mention a current idea he felt might be of interest. I consulted with him on many decisions important to me and often took his advice. We shared countless friends … Keith Sonnier, Joey Ramone, Lawrence Weiner, Dennis Oppenheim, Laurie Anderson… and we remained in touch throughout his life. I spoke to him three weeks before died. He was greatly upset about the death of Bill Fagaly, a much-loved curator at the New Orleans Museum of Art, where Diego served loosely as a curator of photography. Neither of us spoke of his own approaching finale but for the first time in 50 years, he didn’t propose a new project or idea to me, and I didn’t ask him to do another show.

I hope that, like Elvis, there will be continued sightings of him.

Alba Clemente

JAMES CURTIS ALIAS DIEGO CORTEZ

I used to joke with him that, choosing that name, he had given himself a destiny.

His love for traveling and his conquest of the art world.

Everyone loved him; his intelligence, his knowledge, his humor, his sensibility, his openness, etc…

The only other thing he really enjoyed as much as art was food.

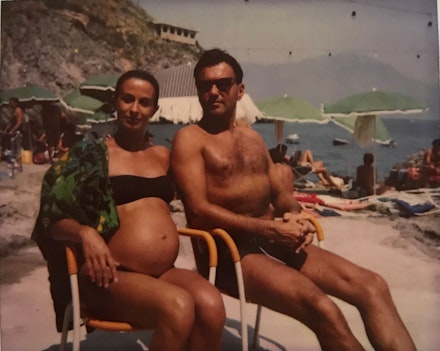

He used to say, after his third plate of delicious spaghetti a vongole, in a restaurant in Capri, Italy,

“It’s okay … I can still see my feet!’

Referring to his tummy.

WE MISS YOU DIEGO, THANK YOU SO MUCH FOR ALL THE GREAT TIMES WE HAD TOGETHER

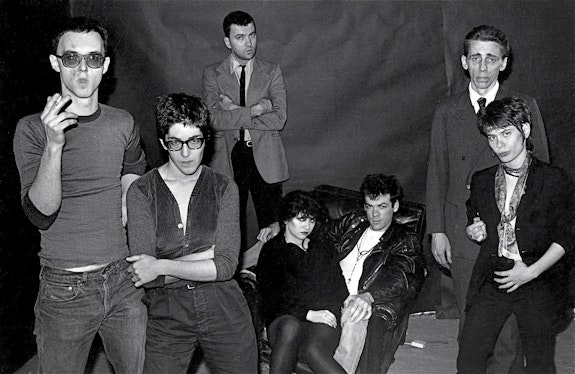

Ann Magnuson

I had such a crush on Diego. I’m pretty sure we first met at the Mudd Club. But maybe it was at Club 57? He came there often in the early years—1979 and 1980—when I was the manager and was also organizing art installations, performances, and other events. Or maybe I first met him at CBGB or Max’s while watching the now-legendary bands we all loved? Or was it through the myriad of friends we shared? Or maybe it was from just bumping into him on the street? That happened a lot.

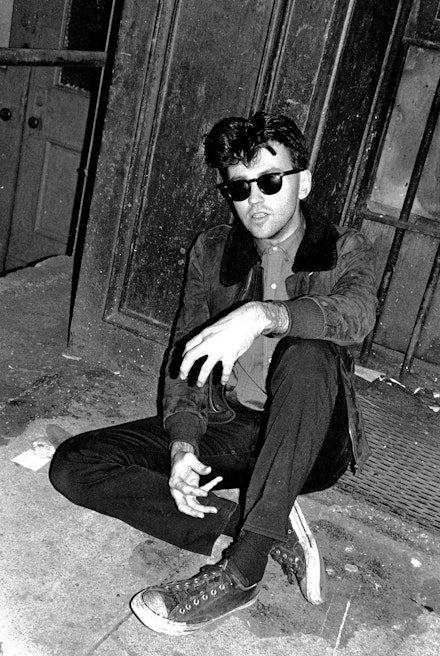

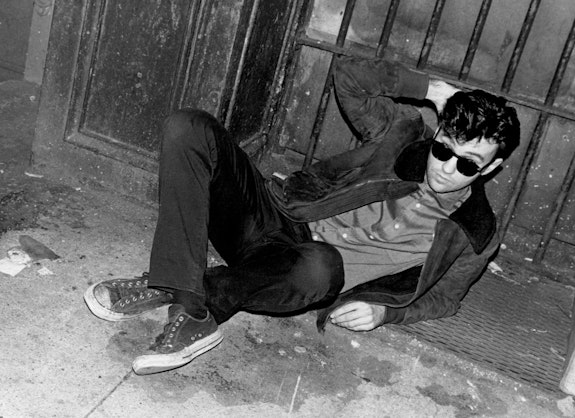

It was easy to become friends with Diego. We hit it off big time. We were both talkers and eager to share all the things we had learned in school, or knowledge acquired over the years, or just sharing something we saw that day or night that excited us. Finding kindred spirits in the downtown art and music scene at that time in New York was such a thrill. Hanging out with Diego was an extra special thrill. Diego was super cool and super smart, and so plugged in! Every conversation we had was exciting. He was one of the first people I knew who dressed in the vintage 1960s suits and skinny black ties that made many of the hip guys in downtown New York look like they just stepped out of a Jean-Luc Godard film.

Boy, was he a charmer. I will admit at the beginning he gave me goosebumps. I was upset when I found out he was gay. That happened a lot too. It seemed like all the super cool, smart, and cute guys were gay. Well, not all of them. But Diego was, and that bummed me out for a minute. It didn’t interfere with our friendship. In fact, it more than likely enhanced it.

Diego enjoyed Club 57, and he was a real booster of what we were up to there. I’d make a special point of inviting him to come when I thought the evening was going to be really great. And he always did. People talk about a rivalry between the Mudd Club and Club 57, but I never really bought into that. Maybe for a few minutes at the beginning until I realized how infantile it was. It was clear that there were cool, fun, and wildly creative people at both places. A few went back-and-forth from both clubs. Diego was the main one. Although he did favor the Mudd Club. Hell, he started it!

The New York/New Wave show he curated at PS1 was one of the most thrilling events of the era. It was jam-packed with art and spectators. It didn’t feel like an art gallery or a museum. Those places were so damn square and boring back then. This show was different. It felt like a club. The most fun club of all! I recently saw Diego’s New York Times obit that lists me as one of the artists in that show. Hmmm … was I? It’s possible. I can’t remember what I might’ve contributed. Maybe it was some art I did for Club 57?

Man-oh-man, that opening was insane! Diego took the creative chaos of the scene and turned it into one big happening of kaleidoscopic spin art! And to be acknowledged by him as a creative entity was a massive boost to the self-esteem. I always felt special in his presence. I always felt SEEN.

He told me he was going to take me to Italy to do a performance at this important gallery in Modena. Wow! That was the big time! I was very excited and devised a performance art piece about America incorporating Kenny Scharf’s DayGlo art. Every time I ran into Diego in the months leading up to the big summer event, he would excitedly say, “We’re going to go to Italy, we’re going to go to Italy!” Then one day Diego gave me the sad news. He couldn’t take all the people he wanted. Just Jean-Michel Basquiat. “But I promise I’ll get you there next year,” he said, as tears welled up in my eyes. He was very kind and consoling. I remember immediately drowning my sorrows in a matinee at the St. Mark’s Cinema nearby. I cried through the whole movie.

After Diego and Jean came back from Italy at the end of the summer, Jean started sporting a new Armani suit with 100 dollar bills falling out of his pockets. That’s when the scene changed. As John Lurie said in the documentary Blank City, “Suddenly it wasn’t cool to be poor anymore.” But even with Diego’s growing importance in the art world, he always remained accessible, cheerful, and fun to be with. I saw less of him as the years passed and our career trajectories went in different directions. But when I did see him, he still had that same twinkle in his eye, the same dazzling smile.

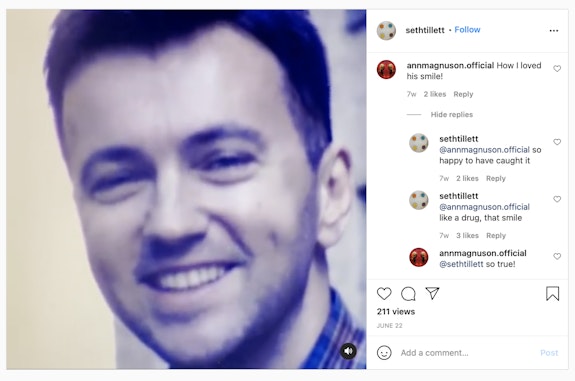

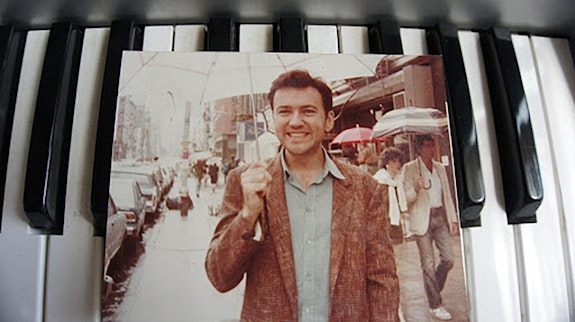

As we aged, my relationship with Diego was intermittent, but always positive. I saw him mostly through social media—now a village elder, an esteemed art historian, wearing his seniority well. I had forgotten how damn cute he was … until his obits came out and his youthful image in those black suits and skinny ties peered out from the past. Then theater artist and filmmaker Seth Tillett posted some rare Super 8 footage he had shot of Diego WAY back when on Instagram. With sound! It took my breath away. There was Diego resurrected, so young and full of life. And so handsome with that unforgettable smile. Through the magic of this grainy Super 8 color film, I was instantly and viscerally taken back in time, serendipitously running into him on St. Mark’s Place and dazzled once more by his charm and exuberance.

And utterly, utterly besotted.

Betsy Sussler

“We were lovers, you know,” Diego would say to anyone who we happened to meet. “Diego, why would you say that?” I’d ask. Unabashedly gay, a vivid provocateur, Diego would answer with a gleeful, sly laugh. I adored him.

We met in 1976, during our first year in New York, when we both worked at the John Gibson Gallery. We used to sneak into the backroom and study the Joseph Beuys Multiples stored there. Those were impoverished years; we ate the same meal every night—Diego cooked spaghetti with butter and sausage—at my tenement apartment overlooking St. Patrick’s Old Cathedral and its cemetery.

Diego had a prestigious MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, but he was always defiant and irreverent. Devoted to art, he was its staunchest defender against opportunism and greed. Diego could be harsh yet beguilingly humorous in his assessments, and stunningly self-destructive when cornered. Regardless of the cost, Diego’s impassioned convictions were innate to his spirit. Sometimes I’d have to wonder how he’d resurrect himself this time. But he always did.

All of us who had the privilege of sharing in his friendship, his abundant humor, his agile wit, his acute intelligence, his capacious appetite for life—for controversy, for great food, for groundbreaking art, for joy and laughter—and, yes, even his ironic, edgy judgments, will never forget him.

Brett DePalma

HE TOOK the A TRAIN

Like a hayseed, I blew into Manhattan from Nashville in 1978. I met Diego Cortez at a seamstress shop while he waited in his underwear for his only pair of black pants to be hemmed. Diego introduced himself. I replied with “Pleased to meet you,” to which he replied “How do you know?” I knew then James Curtis was not someone to take for granted!

Like the poet Virgil, he asked me if I wanted to go to a rooftop “underground” party in the Lower East Side. It was termed a “new wave Vaudeville event,” where the no wave Teenage Jesus and the Jerks mingled with men dressed in ’40s thrift store suits and women wearing vintage punk dresses. We left when someone actually fell backwards off the roof, breaking both legs. Meanwhile, in Keith Haring’s kitchen, I watched provocateur poet, Rene Ricard, confront Diego with “You don’t know who I am,” only to meet Diego’s quick retort, “You don’t know who YOU are!” Welcome to the NYC downtown underground, my soon-to-be larger family.

Diego revealed himself to be an artist, filmmaker, music aficionado, consultant, collector, and adviser. Later, while working at the blue chip gallery, Sperone-Westwater-Fischer, I saw him confront Sperone to reimburse him for airfare to Rome, where a show of his work had been cancelled. He got paid for a show that didn’t happen! Thus defining Diego’s phenomenological relationship to money: he spent it in order to make it!

Diego would later hand-cut hundreds of glass panes himself, as the framing curator of the ground-breaking New York/New Wave exhibition. Herein, he opened the door for the likes of Basquiat, Byrne, Haring, Graffiti, Mapplethorpe, et al. Diego would later escort me to Steve Mass’s control room to consult with Dr. Mudd about the plans for the club below. I would meet Diego’s boyfriends from Jimmy DeSana to Massimo Audiello, and watch as he declined the offer from Madonna to manage her. Google his CV!

Diego’s death leaves a huge hole where once was an expansive mind, steeped in Art, Music, Literature, and Sociological Schizo-Culture. In his wake, he leaves Waves, still lapping at the Albion shores of NYC and the world.

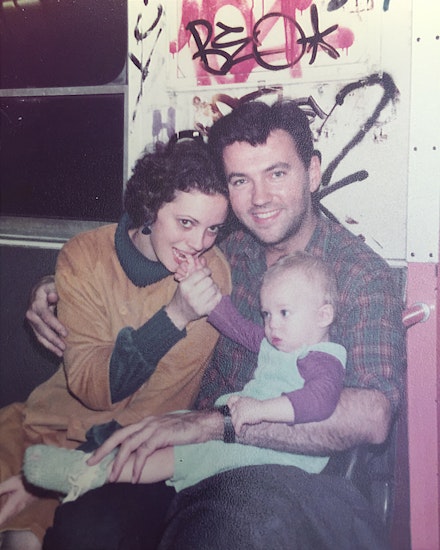

As Jean-Michel referred to him, he was “Jimmy Best on his back to the suckerpunch of his childhood files.” I prefer to think of him as someone who “took the A train” Uptown to the next station, only to meet him on the way Downtown with my small family.

Brian Eno

Diego was the first person I befriended when I found myself in New York in 1978. I’d come for a week and ended up staying five years. Some of this was down to Diego—a kind, mischievous, and funny man who was at that time at the heart of the Soho scene (this was before Soho had become a shopping mall).

It was Diego who told me about a sublet on 8th Street— floor above the apartment of Steve Mass, who was at that moment cooking up the Mudd Club. I lived for over a year in that sublet, on what seemed to me one of the most exotic streets in the world. It was through Diego that I met Arto, another dear friend. They were a great pair; a wall of cool.

Like most interesting people, Diego was a tangle of contradictions; he had a deep natural kindness and affection which he disguised by a façade of mischievous cynicism and nonchalance. He made fun of everybody to their faces—but it was OK because he made fun of himself too.

When I think of Diego’s face I think of a naughty smile, a self-deprecating humour, and a sharp but never flaunted intelligence. Diego always made me laugh, but he always made me think too. He was further ahead of the cultural curve than almost anybody else I knew—always pointing me towards things that I often initially didn’t get at all. He was a sort of cultural pilot who led me and many other people through the turbulent waters of modern painting.

He was also effortlessly charming and managed to talk me out of the only half-decent self-portrait I ever made—an almost invisible 6H engineering pencil drawing that he professed to like so much that in the end I had to give it to him.

It wasn’t until I started writing this that I realized how much I’m going to miss him.

Brooks Adams

In the ’80s, Diego Cortez was all animal magnetism and Diaghilevian brio, a self-invented punk Svengali who swept you up in his entourage and took you to places you’d never been. In June ’89, Lisa Liebmann, Ricky Clifton, and I decamped with him from the Venice Biennale and headed south in a rented car. (With Diego you left La Serenissima in a water taxi, never a vaporetto.) On the autoroute, Diego was like an apoplectic traveling salesman behind the wheel: always in a hurry, often impatient. There were many spats along the way, with both Lisa and Diego getting out of the car in huffs; never suffering fools gladly (except when they were young and cute), Diego was in his saturnine prime.

The first night was spent in Tuscany at Sandro Chia’s castle in Montalcino amidst the artist’s vineyards; the second at the Hotel Locarno in Rome where Diego, rumpled in unpressed seersucker, took a meeting with a dapperly suited Enzo Cucchi in the hotel garden. The third was in Naples where we went to a banquet at gallerist Lia Rumma’s stripped-down Baroque palazzo; the fourth in Capri where Diego was renting one of Paola Igliori’s many family houses: basic, but with an impeccable pedigree.

While in Naples, we took a taxi to Philip Taaffe’s seaside villa in Posillipo for drinks. (In spring ’89, Philip had had a brilliant double show at Pat Hearn and Mary Boone in New York; the catalog featured an essay by fellow expatriate Gore Vidal.) Here in the gloomy Villa Peirce at sunset with a view of Vesuvius, Philip was attended by the sycophantic and unscrupulous assistant who had once been an extra in Federico Fellini’s movie E la Nave Va (1983). With Philip’s huge Pompeiian-pale paintings presiding over otherwise deserted rooms, Diego, against some rather stiff competition from the effervescent Ricky and the dour assistant, prevailed as the louche master of ceremonies.

When on April 22, 1993 Lisa and I got married in Philip’s cavernous West 30th Street studio, Diego was of course on hand to give a toast. It turned into a long-winded, evangelical tirade about the Branch Davidians, those Seventh-Day Adventists who, just two days before, had seen 76 of their members go up in flames at their stronghold in Waco, Texas. How like Diego to turn a wedding into an apocalypse, but then one had to remember that he was first and foremost a performance artist. Like Marjoe Gortner, that handsome Pentecostal preacher and the subject of the documentary Marjoe (1972), Diego was a charismatic ranter and raver with an eye on the till.

Coleen Fitzgibbon

Early Diego

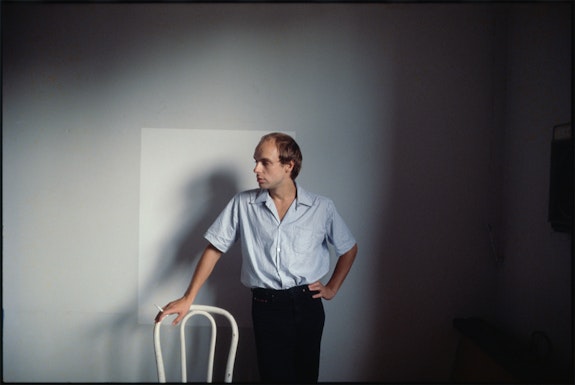

I met the slender boyish Jim Curtis with long black hair around 1972 when we were at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and he was in the MFA performing program after studying theater at Normal U of IL. Jimmy was an incredibly funny, compassionate, and talented artist who everyone knew and was drawn to. His face resembled Presley-Burton-Morrison and he had a wicked wit and infectious laughter—he always knew everyone anywhere he was and they him—he was well-loved early on.

In Chicago we would go dancing all night at the dance clubs and he would say “just dance—it doesn’t matter how” and then get everyone to dance together with joyful outrageous abandon. We lived in the only two standing buildings on our industrial block across from a grommet factory that hired Mexican workers, our neighbors, and we took turns organizing neighborhood film shows of Kenneth Anger and experimental movies on hot summer nights on my building wall. This may have been the beginning of the identity of Diego Cortez.

We lived in a dangerous neighborhood and one time alone at night he saw five big guys approaching him scowling. He said he continued to walk straight towards them and at the very last moment with only a few feet between them he stumbled theatrically. They backed up and then laughed and he kept walking.

Jim did several brilliant performances of Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape in his studio and I realized then the depth of his art. After he died I thought of his careful inventorying of his artworks (he had sent me slides of him organizing them) and his interpretation of Krapp.

We were also both making films, and he started on a series of dead animal films that he encountered on the street with dirge organ music he composed on his keyboard. Once Jim took care of my bunny while I was away, and when it died of eating Styrofoam he made a “Dead Rabbit” film.

Between ’73–’74 most of us at SAIC (Christa Maiwald, Marjorie Keller, Saul Levine, Bill Brand, Francis Naumann, Gregory Lehman, Laurie Simmons, Jane Kaplowitz [later Rosenblum], Diego, and myself) moved to NYC—Diego and I moved into a commercial sweatshop building at 195 Chrystie Street; for a year I had a hammock and he had a brass bed. The first winter we were there it was freezing, the landlord would turn on the heat during holidays and weekends, and Diego would call Jimmy DeSana to come save us and let us sleep in sleeping bags in his battleship-gray apartment with Salvador Dalí portraits. Jimmy and Jim were very close then and it may have been a final turning point into the birth certificate of Diego Cortez.

Diego brought me to the salons of Richard Foreman/Kate Manheim as well as Nam June Paik/Shigeko Kubota, as there were the things he liked best: good artists, good drinks, and good food. We were hired briefly that year by John Gibson to clean up his gallery and inventory the art; John sort of took Diego under his wing during that period. I doubt John knew that Diego and I occasionally cleaned the gallery wearing the Joseph Beuys felt suits.

Diego helped Jean Dupuy organize the 1974 Soup & Tart performances as well as performing in the series; I remember two, both startling, with Nam June precision—one where he pulled out a clean white handkerchief, crumpling it in his hand and pulling it back out with a blood red spot on it, and a second where he stood still as blood slowly appeared on his lips. In 1982 the first person Diego knew to die of what we didn’t know was AIDS was Gordon Stevenson of Teenage Jesus and the Jerks; by the mid-’80s with the downtown AIDS crisis Diego’s performance seemed very prescient; he was close to many of the artists who died.

In the mid-’70s Diego started working with a brain surgeon and made several eerie, experimental films and tapes of brain scans with moaning that were shown at Anthology Film Archives and Millennium. He also published a book of photos of Elvis Presley called Private Elvis where he had bought the negatives of Elvis Presley in Germany and manipulated the photos to add enlargements of the hands and mouths. Diego and Anya Phillips several years later made a film at the Presley Graceland compound.

In ’75–’76 Liza Béar interviewed Diego, myself, and Robin Winters separately in Avalanche Magazine. By 1977, young downtown artists who had met in Chicago, San Francisco, the Whitney’s Independent Study Program, or at clubs started Colab with Diego as a co-founder (three years later he was the only member to officially resign with a protest declaration). Diego contributed to FILE Magazine and X Magazine (he also convinced Steve Mass to distribute X to newspaper stands in Steve’s hearse, and to start the Mudd Club). Around this time Diego approached Robin Winters with an idea for making a Batman show at Robin’s loft. It was one of the first Colab theme shows and extremely influential for Jean-Michel Basquiat’s painting style after his graffiti collaboration SAMO with Al Diáz.

After Colab’s Times Square Show in 1980 Diego went on to organize the PS1 show and stop publicly making art, instead concentrating on buying, selling, and promoting other people’s art. A few years before he died he said he was starting to do performances again.

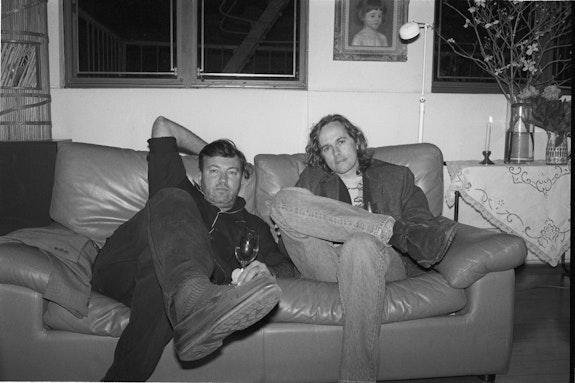

Curt Hoppe

David Byrne

I believe I met Diego in the late ’70s or early ’80s—we had mutual friends among the downtown demimonde. At that time he might have been pegged as a “hanger-on” you know, “what exactly does this guy do?” He always seemed to be where things were happening, whether it was on the fringes of the art world or around the downtown music scene. Although he had the demeanor of Elegua, the Yoruba trickster, full of sly humor and quick to pierce pretentions, like that Orisha he often acted as a gatekeeper who opened doors and made connections. I grew to trust him; beneath the playfulness was a generous heart, and if he recommended something I’d check it out without hesitation.

Diego invited me to be part of the art survey show he curated at PS1. He knew I was doing visual art alongside the Talking Heads, and the invitation was a spur for me to do large prints of some of the photos I’d been taking—almost abstract photos of light fixtures. Sometimes we need a nudge like that, and I suspect Diego provided that for a lot of people.

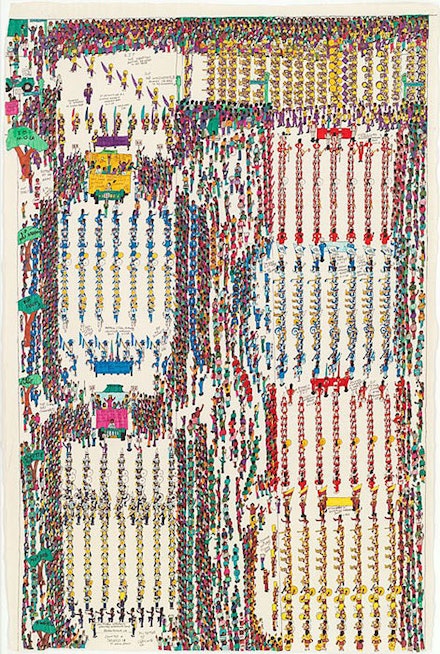

Diego was full of surprises. At one point he had a house in San Germán, Puerto Rico; it was a beautiful place and I stayed there with my family. I heard he moved to New Orleans, and later, I visited him at an elegant apartment that I think was on 148th Street in Harlem. He had become a sometime art dealer, and he showed me some drawings by Bruce Davenport of New Orleans marching bands done from memory. They were a kind of elegy for NOLA culture pre-Katrina. I couldn’t afford the big ones—Mr. Benetton bought some of those I believe—but I did get a modest-sized one. Diego introduced me to a gospel organist named Cory Henry at a church service in East New York—amazing! I managed to get Henry to play at a gala for the Kitchen honoring Brian Eno, who loves gospel music.

Diego’s holiday emails were special. I’m not on social media, so maybe I’m just out of the loop, but these were endless scrolls of lovely snaps of all the people, places, and things Diego had encountered in the past year. They reminded one via a collection of moments of the disparate communities we all accumulate in our lives—occasionally I’d see someone I hadn’t seen in ages—but Diego visited them all.

David Salle

Diego had a great sense of humor. He was funnier than most comedians. There is a type of humor that comes from being comfortable with yourself, with who you are—the opposite of how humor is usually accounted for. Diego’s humor was of the confident type. He was the MC at the wedding celebration for Lisa Liebmann and Brooks Adams, which was held at Philip Taaffe’s enormous studio on 30th Street. Diego killed that night. It wasn’t like what usually happens when amateurs step outside their areas of expertise—Diego was really funny. He had many gifts, in fact. Diego also had a good, if undeveloped, operatic tenor voice, and could convincingly sing the arias from famous operas, a capella.

He was insightful, one wants to say even visionary about art, but his real gift was for how to live. He seemed to have houses or apartments everywhere, all with beautiful furniture and of course lots of art. How he paid for all these places was a little bit mysterious, and at times may have bordered on grift, but that was part of knowing how to live. And whatever the transgression, Diego was always forgiven because he was also very generous himself. Anyway, life was a group project, and he always did his part and more.

Diego wrote a text to accompany a catalog of mine for a show at Gagosian in the early ’90s. It was completely unconventional, more of a short story than a catalog essay, an unparalleled act of critical empathy. I’m only just now beginning to understand the depth of feeling that went into its composition.

Diego had the gift of being in the right place at the right time. His grace was to know which things to take for granted and which things to approach with humility, which is a strange word to attach to Diego, because he didn’t often show it. But that just meant that he knew it was in short supply in our world, and he was saving it for when it was really warranted.

Devendra Banhart

I had shown only a handful of times, and my first album had yet to be released when I first met Diego …

I remember it being one of the first shows I had ever played on the East Coast. I had a few advance copies of my album, and he asked me about the art on it. I told him I had done it, and he immediately asked to see more work. The thrill of that question was eclipsed by the shock that someone was actually asking me to show them my work? What? I literally had only known the inverse of that situation till that moment …

Soon after, Diego called about possibly showing my work in Italy. I have to stop here and say that four years earlier, the Basquiat film had come out and I was well aware of who Diego was and how instrumental he had been in helping Basquiat’s career. What a legendary curator, collector, and general go-between-all-around art facilitator he was… but I really didn’t think any of this could be real. Here’s this extremely charismatic guy with the best hair I’ve ever seen telling me in the most gentle, matter-of-fact, down-to-earth way that he’s gonna make a few phone calls and get back to me about an art show in Italy …. What? Oh, but first he’s gotta go meet up with (here you can insert the name of your favorite artist of all time as I guarantee that Diego was friends with them and they regularly had dinner together.)

But, sure enough, I soon after had my first show in Europe, all 100 percent thanks to Diego. This was over 20 years ago, we worked together so many times after that. I can 100 percent say that I owe my entire art career to him. This is just a fact I wanna get out. As for my friend Diego …. That’s something quite different …. I didn’t love him because he was the first person to believe in my art. I didn’t love him because he fought for me and brought my work to places I would have otherwise never in a billion years had access to. I loved his being, his heart, his humor, and his way of flowing from one moment to the next. He was my true friend, and it’s a desolate place without him. It’s all a bit too soon to write anything beyond the mute-making heartbreak of his absence …

Francesco Clemente

Diego Cortez was an American Rebel who refused to die young.

If he had died he would have had to stop laughing with his friends, and there was always so much laughter with Diego. He would have also had to miss his daily Italian lunch at Silvano’s, an unfriendly and overpriced restaurant which mysteriously kept an open tab only for Diego. He would have missed his delightfully bright Italian boyfriend, Massimo, who became a brilliant gallerist and who is grieving now, many years later, having enough sense of poetry to remember that, when young and in love, the bad days were as good as the good days.

Somewhere in Chicago a quietly deranged urbanist utopian mind has generated a landscape of perfect little houses, equally distanced, spaced all the way to the horizon, equally painted in gray and beige, timeless and simple like the drawing of a child, minus the bright colors. Diego Cortez grew up in one of those Chicago reasonable houses, nests of the modernist dogma, stretching evenly in every direction under a wintery sky. Where then, did Diego discover beauty? It must have been watching the light change over the face of a boy or of a girl crossing the room.

After the war, famous American artists, whose exhibitions abroad were funded by the CIA, were famously indifferent to the local context. When Warhol, in an interview, was asked who his favorite Italian artist was, he replied: “Valentino.” Young artist Diego Cortez visited Italy too. He met Boetti who introduced him to others saying: “You must meet this young American who is very unusual, he is actually interested to find out what goes on here.”

Diego showed Boetti his work: loose sheets of technical manuals depicting tools and hardware, stained with Diego’s blood. The works betrayed a mind eager to compile and to collect, they were relaxed, in the family of Cornell or Ray Johnson but without the drama or the ambition.

America is a serious place. Artists take themselves seriously and that is why they feel at ease in America, they stand out less, they appear less grotesque in their exaggerated self-cherishing. To continue as an artist, Diego Cortez would have had to take himself more seriously than he was capable of. He had not chosen the name Diego Cortez because he wanted to conquer, acquire, accumulate. Rather he wanted to be a Conquistador because he wanted to leave a trail of scorched ground behind him.

Usually prophets are taken seriously after they are dead. But Diego Cortez, American prophet and rebel, did not die, he was protected by his sense of humour, by his curiosity and by his faith in Art with a capital A.

He embraced the artists of his own generation, for them he became an impresario, a curator, a critic, a friend. Once an artist who had just arrived in New York for the first time wanted to gather for his exhibition a group of emblematic portraits. They were going to be emblems, like tarot cards, but at the same time depict a particular person, painted from life.

The artist did not know anyone in New York except Diego, whom he had met briefly six years earlier in Boetti’s studio in Rome. Diego offered to organize the casting of the show: within two weeks fresco portraits of Taylor Mead, Jimmy DeSana, David Salle, Terence Sellers, Julian Schnabel, Keith Haring, Fab 5 Freddy, Edit DeAk, and many others filled the gallery. When David Byrne told Diego he would not sit for an almost unknown artist from Italy, Diego replied: “You just want to be another rock star.”

When Diego dismissed a talented and promising friend saying: “You just want to be another rock star,” what he was really saying was: “Watch out, because to succeed means to fail.” And here a shadow comes into the picture: over time, Diego Cortez cheated most of his friends, on one occasion or another, even after many years of friendship, even if he knew he would be found out, even if the material gains were risible. This cheating was not a cheating but rather an instinctive way to say: “I betray you because you betrayed yourself.” I betray you because all of you, my artist friends, to be able to make art, betray Art. You accept imperfection, you accept to be part of a system of normalization which is in the opposite camp, has the opposite goals of everything you believed in when you began. I, Diego Cortez, could have been as good an artist as any of you, but I chose the perfection of life over your petty strategies of make-believe. I broke the rules but I kept my integrity and, as I part, I can still say, in the words of another rebel: “Beauty is mine, perhaps one day you shall find it.”

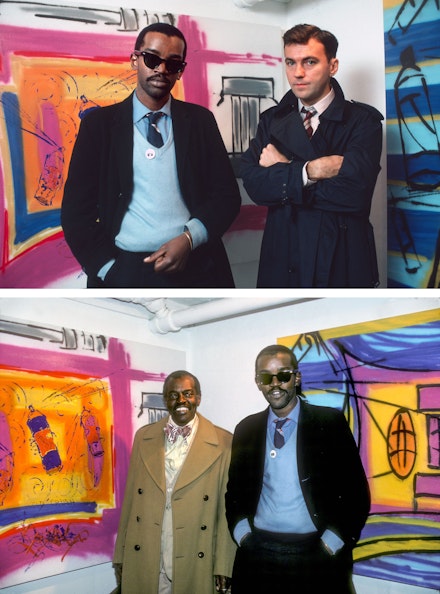

Fred Brathwaite

FAB 5 FREDDY: DIEGO CORTEZ, R.I.P.

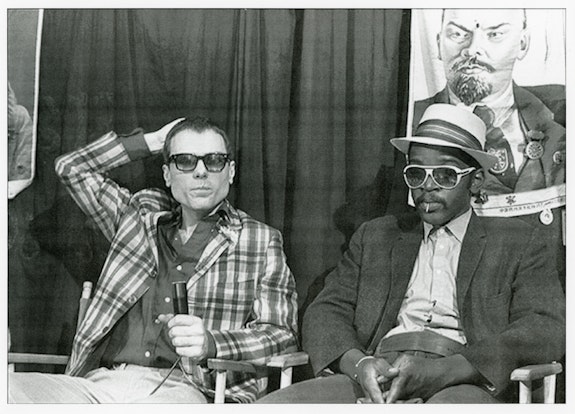

I first met Diego late ’79, early ’80 and I have to say, Diego was a brilliant visionary. I met him on the set of Glenn O’Brien’s TV Party, an underground public access cable TV show. I was a part of that crew, one of the cameramen, and I was also a frequent guest on the show where I met and became friends with many of the key downtown scene leaders. Diego was hanging out with his good friend Anya Phillips, and Diego’s name and what he was doing had already hit my radar really hard. I had that special issue of File magazine—“File Goes to a Party with Diego Cortez,” (1977). I think Diego was one of the editors of that issue and there were lots of cool photos of him and so many other major players on the scene. Debbie Harry was on the cover of that issue. One of the first things we discussed was his name, and I asked if he was Spanish or Latin as I’d recently read about Diego Rivera and the Mexican muralists. He told me he loved them as well and took that name because of them but his real name was James Curtis.

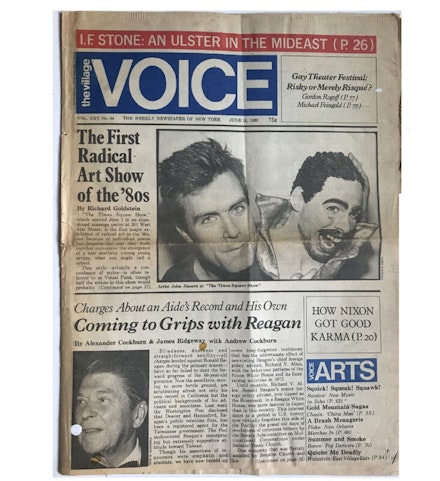

Diego was aware and curious about things I was doing culturally like collaborating with Lee Quiñones on our first exhibition, a two person show at a prestigious gallery in Rome, and introducing these new New Wave friends I was making to this new music scene soon to be called “Hip Hop” happening in Harlem and the Bronx. Diego was fascinated about all of this and wanted to know more as we quickly became friends. Later, I had my first solo show at the original Fun Gallery. I was the second exhibit that happened at the Fun, following Kenny Scharf’s first show. The idea was that all the artists would get to name the gallery when it was their exhibition. Kenny’s was the first exhibit and he called it “Fun”because that was the theme and idea of his work. Being that my show was following Kenny&rsquos, and since we were all trying to be a bit different, I was going to switch it up and call it the “Serious Gallery.” But Patti Astor had no money to change the stationery and the things that she had created for Kenny’s show, so she asked me would it be alright if she kept the name “Fun” for my show, and obviously it remained the name of the gallery, so that was the deal.

The Fun Gallery was my first solo show in New York, and Diego came to the opening, and was very enthusiastic. My dad also came to the opening, and he was fascinated to see these moves I was making: to go from writing my name on the walls and the trains to painting on canvas and having a show in an art gallery. It was a really fun affair.

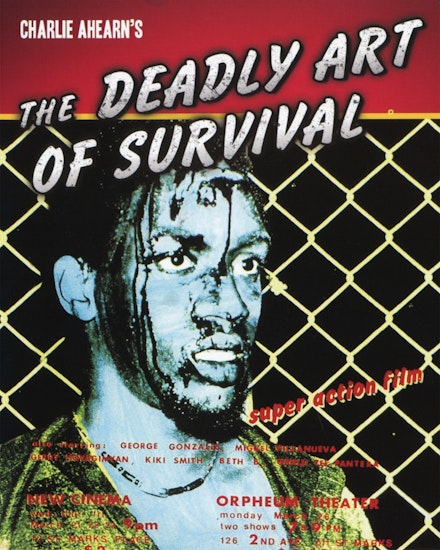

A little later that year, I got word that there’s this huge exhibit coming up called The Times Square Show. In fact, it pretty much debuted as a cover story in the Village Voice. The headline read, “The First Radical Art Show of the ’80s.” It was pretty exciting, the way the show was written up. Right away, I thought, “Wow, I gotta see this.” Even though I was a young fella, I had done a deep dive into art history, so I knew all about the Armory Show in 1913 and Marcel Duchamp and how pivotal that show was in introducing modernism to the art world in America. The way this new show was being written up, it seemed very pivotal in the same way. I thought, “Oh my God, I have to see this show, I’d love to be part of this scene.” I had a conversation with Diego and he said, “I know the people that put it together,” and the first event was happening later in the week, and he invited me to accompany him.

I went up to Times Square with him where the show was being held in a former massage parlor—actually an old whorehouse. As I walked into the exhibition, art was covering every square inch of the space in a very engaging way, and there were loads of people all over the place, many coming up to Diego and saying hello. A well-attended art event and one of my first. Suddenly, on the wall, I see this poster for a film called The Deadly Art of Survival. Now, one of the ideas that I was developing with Lee Quiñones was that we should make a film like one of those underground independent movies, a movie that would show who and what we really are and what we really do. Controlling the narrative. I wanted to showcase all these elements of what we now know of as hip-hop culture—all the stuff that was just beginning to poke its head above ground, so to speak. But the thing is—I’d seen this poster before in Lee’s Lower East Side neighborhood. The image on the film poster was a Black man in a park in front of a chain-link fence with blood dripping down his face. Lee told me he knew this guy as a local Kung Fu hero who had a karate school in the neighborhood near Lee’s projects. So when I saw this poster at the Times Square Show, I said to Diego, “Man I’ve seen this poster before, what’s up with it?” And Diego says, “Oh that’s a film by Charlie Ahearn, he’s the twin brother of John Ahearn, one of the people that organized this exhibition.” When Diego pointed him out, I realized he did look just exactly like the guy whose face was on the cover of the Village Voice. So Diego introduces me to Charlie Ahearn and I basically pitch him the idea for what becomes the movie Wild Style. Charlie was aware of Lee’s work as he had filmed some of that movie in Lee’s neighborhood, and he was enthusiastic and very receptive. A few days later, Charlie and I got together and began pre-production on Wild Style, the film that really puts a whole frame around what we know of as hip-hop culture. That’s one of my first major situations, and that was thanks to Diego Cortez.

But Diego had a rival sensibility with the Colab crew that put on that Times Square Show. As we left the exhibition together, he was already muttering about how he’s going to show them how to really do a proper art exhibit showcasing many of these artists, most of whom Diego knew well. That’s when Diego started planning the New York/New Wave show, which would happen a year later at PS1 in Queens, literally the first major downtown blockbuster art show. Although it wasn’t actually in downtown NYC, it was totally that downtown sensibility. Diego featured my work and several other graffiti painters, and of course Jean-Michel Basquiat was prominently featured in that show, and that really helped launch this whole assault in the New York art world. Diego saw it early, got it, and understood it clearly. He was an early champion of everything we were doing.

Now, there’s one other thing I want to add to this little story, and Diego didn’t let me know this until a couple of months later, and neither did my father. Diego was fascinated about meeting my dad at that Fun Gallery opening. I was still living at home at that time, and not long after was living in my first apartment in the Lower East Side down on Clinton Street. Diego had my parents’ number which he used to reach me, so he called up my dad at home in Brooklyn and invited himself over, to come and hang out. He took the A train way out to Bed-Stuy in Brooklyn and went to the house where I grew up and spent an afternoon hanging out with my father, who regaled him with all these stories about growing up in Brooklyn, the jazz scene, and stories about Max Roach, the great jazz drummer who was my godfather and my dad’s childhood friend. Bed-Stuy was solidly a Black working/middle-class community then, yet it was depicted in the media as violent and very dangerous, which it wasn’t. Gentrification has changed that perception significantly now, but Diego was fearless, unbothered by the hype, and had a blast.

And that’s just a little slice of my dear friendship with Diego Cortez—early champion of what we were doing, of what I was bringing to the table as a visual artist, of hip-hop culture, and the whole idea of this new movement bringing artists of color into the cultural mix. Diego was a champion of all these ideas that I had, that hip hop culture was connected via energy and spirit to what New Wave and punk were all about—breaking the old rules and making new ones. Diego was there early on, full on, a total supporter, who always had a great smile on his face, always had great jokes; we were always laughing, always cracking up. He was always going on about so many topical issues happening in our scene, and in the world, and he hated all the bullshit going on. He hated all the racism, what it was like for artists like myself and Jean-Michel, that we were being treated with so much love and respect in the scene at that time, but then we would walk outside and taxi cabs wouldn't stop for us. There were things that were changing, that were really advanced in our scene, but then the world that we lived in, still live in, still has problems. Diego was not having it, and he was not afraid to just basically speak out.

That’s it, Diego Cortez. Love you, miss you, and we will never forget the incredible impact you had on us all. Thank you.

Ingrid Dinter

Perhaps his reputation preceded him, or his zeitgeist was simply pervasive, or like the wind in the subway which blows through the station in advance of the coming train … he was around.

I had come to NYC in May 1978 as part of a group from my art school in Germany, Staedelschule, in Frankfurt am Main. The school had an exchange program with Cooper Union and at that time Gerhard Naschberger was on deck. We had quite a program for our visit, which included amongst other things a pilgrimage to 420 West Broadway, and of course a stopover at Fanelli’s. It was at Fanelli’s that Gerhard introduced us to Donald Baechler and Jiri Georg Dokoupil, two fellow students at Cooper Union at that time. I also remember visiting Printed Matter on Lispenard Street—it was a tiny slip of a space with a very DIY ambience, including the artists books. We also went to a performance at 112 Greene Street, which was something to do with a naked defeathered ready for the pot chicken, which ended with the punchline “an abscess makes a fart go honda.” We also visited Max’s Kansas City and CBGB’s, and went uptown to stand in front of Studio 54. And so much more.

All that as preamble to—after several visits in the next couple of years—arriving in the City to stay in January 1981, on the day that Ronald Reagan was inaugurated. Shortly after that I recall being at PS1 in deep snow for the opening of “New York New Wave.” That was the arrow in the bow that shot off to become the 80s. Diego had genius, or good mojo, or the vision and/or strings in his hands, or even just interest and will, or all of the above, or more, to make things happen.

The next exhibition of his that made an impression on me was at Marlborough Gallery, The Pressure to Paint, combining the works of current European artists with artists currently working in New York City. In fact, in my view, the end of the ’70s and early ’80s was a major sea change in artmaking, internationally. Probably just the result of a new generation coming up. Before coming to New York City in 1981 I had seen the work of Chia, Cucchi, and Clemente at Paul Maenz Gallery in Cologne. I had been to the Venice Biennale in June 1980 and seen the work of Kiefer and Baselitz at the Germania Pavilion—Klaus Gallwitz (who recently passed) was the Commissioner of the German Pavilion at the Venice Biennale through the mid and late ’70s; he was also the director of the Staedelmuseum, adjoining the art school—a group of us lowly students were invited each time to go to Venice to watch the installation at the Germania Pavilion and attend the previews. I remember seeing Lucio Amelio and Joseph Beuys at the 1980 previews, and running into them later around town. Six months later I moved to New York City, at which time the European American exchange was in full swing.

Diego was in this axis. Being in right places at right times, and having a good intuition/perception. And also the interest and the will to make things happen.

Skipping along, now it’s September 1984 and Pat Hearn has asked me to work for her in her original gallery, on the corner of 6th Street & Avenue B in the East Village. She had opened it a year before. I was her first employee, and the operation was still quite small. I pretty much took the administrative burdens off her, so she could free up to do what she did best: sell art. The season opener exhibition in September 1984 was Philip Taaffe, his first solo exhibition and introduction to the art world. The show attracted attention, a lot of people came to the gallery, and for the next year and some months that I worked there (and in the new gallery on 9th Street) I watched a parade of art world heavy hitters stop by.

When I started to work for Pat the presence of Diego Cortez was very obvious, and right next to him Massimo Audiello. Massimo connected to Pat in very close ways, some of it a kind of mentorship on her part, as he seemed to be prepping his launch as a gallerist coming up.

The story that I heard, or remember, true or not, myth or not, is that Pat and Diego crossed paths the summer of 1984 on the beach in Newport RI. Pat was from Providence, so being in Newport in the summer would be natural. There they hit it off, and to some degree joined forces going forward. I’m sure Diego’s input helped guide Pat on her path as a gallerist. I can imagine him saying “you should …”. And Pat astute as she was, would know instinctively what to heed. But I always perceived Diego’s presence to be in the background, behind the scenes, under the radar—forceful as it might have been. And anyway, I’m sure Diego always had lots of other irons in the fire ...

A couple of the shows I credit him with influencing at Pat’s gallery during the time I was there, or soon after I left (in early February 1986), would be “Otto Piene, Enrico Castellani, Günther Uecker,” and a Sam Doyle exhibition. Those stick out, though there were surely others as well.

When I went to work for Pat I was still a post art school would be artist trying to forge my path in the art world. That was tucked away in the back pocket as I presented as the gallery assistant—answering the phone, for one. This was my first experience answering a gallery phone. It is an empowering experience. You get to know everyone very quickly. Also, suddenly you are quite popular and have tons of new friends. This was the transition from outsider to insider in the art world—privy to much. And once you are in, you remain in.

Diego acknowledged me, and at least from then on forever he never failed when he saw me to say “hello Ingrid”—even if it meant stepping aside from whomever he was talking to and to say that with a little kiss to the cheek. Two other artists come to mind who did the same—Ross Bleckner, and Jeff Koons. This display of very good manners never failed to impress.

Whatever else Diego went on to after passing through Pat’s orbit, he always followed his own path. I wasn’t close to him, didn’t see him often—I wasn’t necessarily out that much—but now and then, in passing, in a restaurant or some such. I remember his stance, with arms crossed across his chest, and slightly something with the feet—flat feet, or so. He was such a handsome guy, but as time went by he didn’t seem to care all that much about his physical self—he got chunky, hair a mess, beard stubble, but carried on.

Some years later, some years ago, for some reason I googled him, and OMG this bio popped up, which was about 30 pages long at that time. It listed in the most detailed and perfunctory manner every little thing he did in his life, neatly organized by year, and surely in chronological order. I thought he must get up every morning to update it. It was like a diary. Like reading someone’s autobiography, or memoirs. It was riveting, fascinating. Not only did it list the things that he did, but also the offers that he had turned down.

Then there was something about a bookstore, in Harlem? Then he was on FB, but wouldn’t accept my friend request, and other stuff. The last time I saw him, and he was exactly the same as always, was at Bard College in 2018 for the opening of the Pat Hearn & Colin DeLand exhibition at the Hessel Museum.

I always thought of him as a mover and shaker, and a behind the scenes string puller. Leaving a mark on the culture of his time, but without putting himself in front and demanding attention for what he did. Rather, facilitating for others. If he lived well now and then, and had some memorable meals, and conversations, good for him. He had ideas, and he had the wind—or knew how to get it—to blow the boats forward. He will be/is missed—a one and only.

Jane Rosenblum

I met Diego Cortez when we were both MFA students at the Art Institute of Chicago.

He was James Curtis then. I was introduced to him by our mutual friend Jimmy de Sana. Diego was charismatic, handsome, and in love with Joseph Beuys, who I had only a cursory understanding of. After graduating, we all moved en masse to New York. Diego and I briefly lived together at 547 Broadway. Once, we found ourselves without any money to get through the coming week. Diego was completely unflustered, but I was a wreck. Although I saw much less of him after I married and had children, Diego and I spent a weekend together the summer before COVID. He was exactly as I remembered, alternately frustrating and adorable. I will miss him.

Jordan Galland

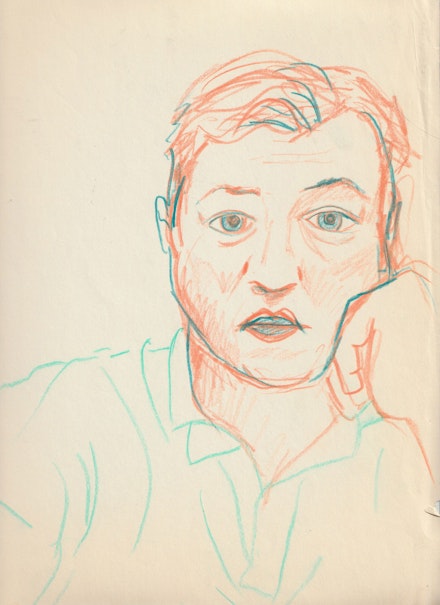

This is a sketch I made of Diego in 1997 when I was lucky enough to be invited to stay for a week at a villa he rented on a cliff in Capri, Italy, which you could only access on foot. He had various house guests but also spent many weeks alone there. He was the first person who explained to me that being alone was not the same as being lonely, that solitude was beneficial and natural, and that while a modicum of sadness should be expected in those conditions, sadness wasn’t a bad thing either. When people asked him what he did in Capri all summer by himself, he would answer with an expression that said it should be obvious: “I read.” He recommended so many good books, essays, and novels, some of which I can still locate on my bookshelf all these years later. Old Masters by Thomas Bernhard, Hamlet’s Mill by Giorgio de Santillana, and Camera Lucida by Roland Barthes are favorites. Others are Art and Fear by Paul Virilio, and Twilight in Italy by D. H. Lawrence, although that may have been because it mentions the villa Diego was living in.

Spending a week with Diego was like an entire semester of the most thrilling college class with the hippest professor, as he’d outline his strong opinions about everything from Gore Vidal to Vidal Sassoon, from MTV to D.H. Lawrence, from David Lynch to Elvis. He was also the first person I knew who videotaped everything, not for sentimental purposes, nor as an artist, but as a way of experiencing the moment from a new perspective. He left me alone, daily, on his terrace where I would stay for hours, trying to write songs, chain-smoking and drinking strong black coffee he made in the morning. I once absent-mindedly burned a cigarette hole through an irreplaceable deck chair that was part of a set of six. I felt so horrible breaking the news to him when he returned at the end of the day. He frowned, understandably upset, scolding me for what seemed like an eternity. Just as I figured it was time to pack my bags, he grinned mischievously and said maybe the owner wouldn’t notice if one chair is missing, jokingly pretending to chuck it over the side of the terrace, where it would have plummeted sixty feet into the ocean-sprayed rocks. I blocked out what happened next in my memory, but I imagine we just walked it into town to get it repaired and never spoke of it again. Or maybe we did throw it over the side.

That same trip Lisa Rosen and Glenn O’Brien came to Capri, stayed with him for one night, and we all went out dancing, the only customers at some small Moroccan-themed nightclub. I’d never seen Diego let loose like that, like it was a high school reunion, recalling the origins of their friendships, the Mudd Club, Blondie, the ’70s and ’80s in Downtown NYC. That night I was witness to these three friends reminiscing about the good old days 20 years earlier, at a legendary time for art, music and culture. Now, that trip to Capri is my good old days.

Kate Simon

I thought he could see into the future, and had a commitment, belief, and intelligence that were inspiring for an artist, that made you work as hard as he did to please him. He was a great impresario and charismatic figure, and the New York/New Wave show he curated, as well as his early belief and support of SAMO (JMB), reflect his brilliance.

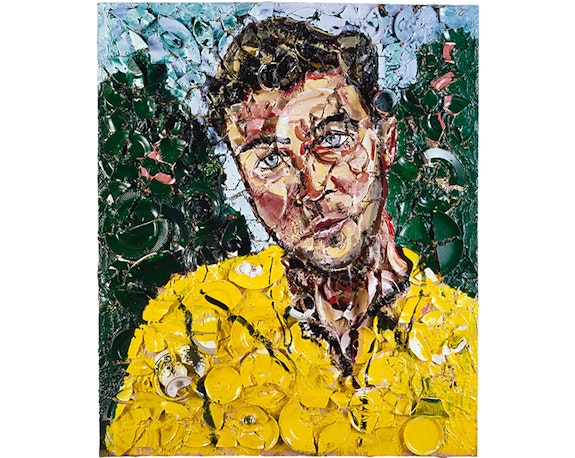

Julian Schnabel

I knew Diego for such a long time it’s difficult to say when I first met him. Probably when I was a cook at the The Locale, when I was trading art with artists so they could eat there and hang out. Diego made this thing called “My Latin Heritage,” it was a typed page and he called it a drawing. I didn’t accept it because it seemed like he made it just so he could get a tab, which was very much like him. But we became really good friends anyway, and eventually I came around and acquired the drawing. Somehow he changed my mind.

Obviously there was the time of the Mudd Club. So much of what Diego was, was formed at that time. The thing that really comes to mind when I think of Diego is what a good dancer he was. He could dance in a very funny and unique way. Peculiar movements, almost making fun of himself. I remember watching him dance at the Mudd Club and thinking, God he’s spreading so much joy and so much fun. That he could just get into it and lose himself, I just loved that about him. He understood the atmosphere that he was in, and he could react to that in a spontaneous way. And I think he had a lot of fun doing that.

Diego was a performer, he always knew when he was being looked at. For example, if he was on a panel, he could say something on the panel that would be so off-the-wall, so outrageous, that he would transform the panel into a performance. I recall one time when he was on a panel with other people, and he started to make a list of things he hated and things he loved. Everything just stopped when he did that. That’s a magic act that he could do, in a way that nobody else could. He was very, very funny.

In the early days you always wondered, was there really a contribution he was making, or was he just hanging around? Was he capable of real insight into art or not? And I can tell you that when he curated a show of mine at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo in Seville in 1988, and wrote the catalog, he was 100 percent there in the best way possible, helping me to realize my vision, ensuring that I got exactly what I wanted. He was 100 percent committed and completely engaged in the art. They offered me a number of different spaces, some very grand spaces, and Diego and I just drove around until we came upon this ruined monastery building which had been converted into an army barracks in the 20th century, and had been abandoned since the 1950s. Part of the roof had caved in, and I threw the rafters out of the window, and then we used them to build a sculpture, called Idiota, which was a huge cross we built together in the middle of the courtyard in that monastery. I have photos of me and Diego lifting this enormous cross up, with all of these workers surrounding it, guiding it with ropes. We pushed it into place and then I painted it there. Diego was working all day with his sleeves rolled up, ready to realize exactly what I wanted to do. Not many curators are like that. I didn't think that much about what he wrote for the Seville catalog, but when I reread it not that long ago, it was really remarkable.

I made a painting of him around this time, a plate painting, he’s very beautiful in it too: he’s slim and he’s got his bright blue eyes. I think he really wanted to be a curator and run a museum, he wanted to be seen as an art connoisseur, and I think that he had very good taste. He guided a lot of important collections. He struggled for people to take him seriously, but when you did, you realized how brilliant he was.

Later in life I didn’t see very much of him, he seemed to be in some kind of self-imposed exile, somehow always on the periphery of things. But Diego had a whole life that I knew nothing about—connections with all sorts of people and places. I remember at one point he asked me to give something to a benefit for Tibet House, and I gave him a painted door that he liked, and then somehow he ended up with it. He was kind of a scoundrel like that. But he was super sweet to me, always. And I didn’t mind him getting something. I was glad he ended up with that work. I never really got mad at him for anything because he was very endearing.

I talked to him a few weeks before he died, he called me to ask for Vito’s phone number. I had no idea I’d never see him again. But I can tell you when he called, I was super happy to hear his voice. I didn't think, “Oh shit, I gotta talk to this guy.” I’m sorry that I didn't get to see more of him, he was a lovely person.

Laurie Anderson

Diego and I grew up next door in twin towns in the western suburbs of Chicago. My town, Glen Ellyn—with a high school in the shape of a castle and a horse fountain at the crossroads—was only slightly less conservative than his, which was best known as the flagship of the evangelical Wheaton Bible College, a school that forbade most music and all dancing. I didn’t know James then but I can easily imagine his irony and flirty charm. We both wanted out as soon as possible.

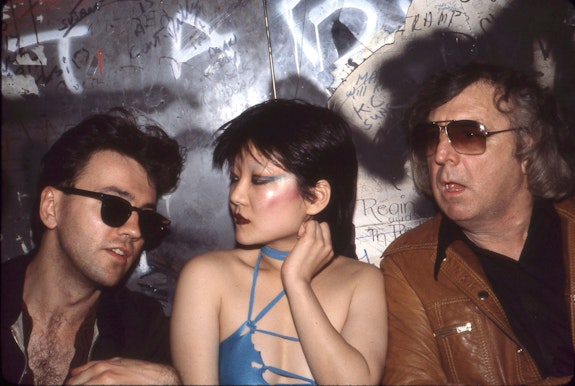

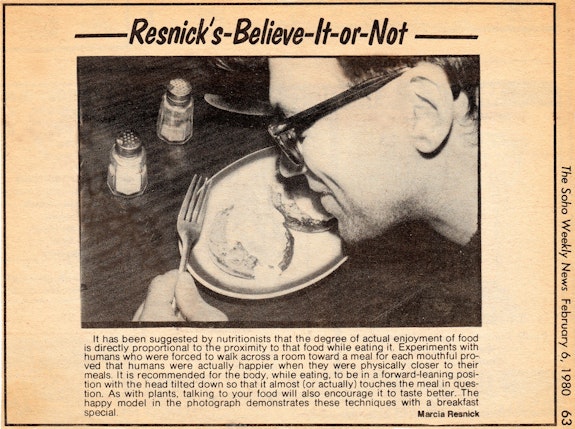

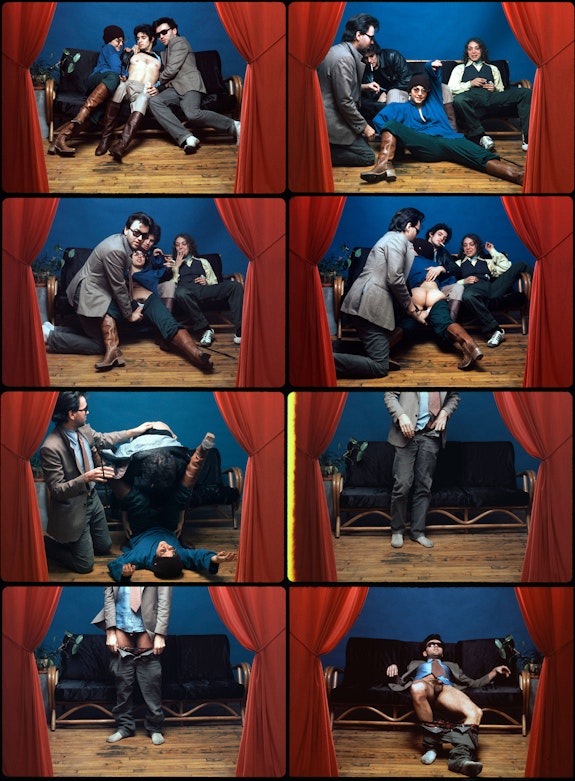

In New York we swirled around each other for years in intersecting scenes and we often met at parties, openings, shows, and recording sessions. He came to lots of my performances and I always trusted his extremely sardonic reviews. He was often in our building for various photo/jam sessions with Marcia Resnick. He was beautiful and vain and hilarious and absurd, always on the verge of laughing.

I wrote a song for him called “Time to Go (for Diego)” because he told me that his job as a guard at the Museum of Modern Art was to go around the museum at the end of the day and ask people to leave—or, as he put it, “snap them out of their art trances.” I loved Diego and told him many secrets. He was such an accomplished listener. So empathetic and smart.

Like many of his friends I loaned him money and he never paid me back. This made me mad, or rather, it hurt my feelings. I truly regret never telling him it was okay, that it was only money and didn’t matter compared to our long friendship. But I never said that.

Linda Yablonsky

Diego was saying, “Darling, I don’t like to be fucked.” He was talking about sex, though he could also have meant fucked in the larger sense, but this was about sex. There had been a mix-up in the sleeping arrangements on one of our several Christmas holidays with Anne Kennedy and Peter Nadin at their Hudson Valley farm. They always had a houseful. To settle the dispute, Diego, ever the gallant, made me a proposal. Why didn’t I cohabitate with him in his upstairs room? It had two single beds, but he was setting the ground rules, as he often did. We ended up with our own rooms, but from that time on he referred to me as his accidental wife. I have to admit that I liked it.

On Christmas morning, we would sit around the tree before a roaring fire and exchange gifts. Every year, Diego gave everyone books. I don’t think he ever helped decorate the tree. Actually, he may have timed his arrival to the hour when he knew it would be done. Mainly, he sipped wine and in his purr of a voice regaled us with amusing stories punctuated by his informed and occasionally stinging opinions. (“They call it Black Studies, but it’s mainly a deconstruction of a sick white pathology.”) I also remember his anecdote about the time he was carrying a tube of twenty Keith Haring drawings and only realized he’d left it on the subway as the doors closed behind him. (Keith forgave him.)

We may have met at the Mudd Club, which everyone seems to think Diego co-founded, but he told me with unusual modesty that all he did was give Steve Mass and Anya Phillips the idea for a place that wouldn’t play disco, which he hated. By that time, he had already established a beachhead in Italy through Alighiero Boetti, who invited him to Rome in 1974, when Diego was a young artist working as a guard at MoMA, and introduced himself on the day Boetti, his favorite artist, visited. In Rome, Boetti introduced him to Francesco Clemente, whom I did meet at the Mudd, in 1979, but the first time I remember talking to Diego was during the opening of New York/New Wave at PS1. I had never been there before, because who went to Queens in those days unless they were driving to the Hamptons or the airport? I had never seen an exhibition that big, and I thought it was astonishing, though he told me years later that the reviews were all horrible, except for the nice things Glenn O’Brien wrote in Interview, which saved Diego from jumping off a cliff. That show meant a lot to him.

Its arrival was delayed a few years earlier by the Modern Art Museum in Bologna, which commissioned it from him originally and then canceled it. Someone—he never said who—told Diego that a spy from Colab (Collaborative Projects), of which he had been a founder (and the curator of its first exhibition, The Batman Show), got a hold of his list of artists and used it for The Times Square Show, which opened six months before his. After that, he made his living mostly as an advisor or agent.

I didn’t get to know him well until the ’90s, when he was having lunch at Da Silvano every day, hanging out with Japanese and Brazilian musicians, and living in Sandro Chia’s building in Chelsea. When he moved to New Orleans a few years after Hurricane Katrina, he curated shows now and again at the New Orleans Museum of Art and lunched at a Cajun version of Da Silvano, where the walls were a very sunny yellow.

I always knew that he wasn’t born with the name Diego Cortez but I thought he lived up to it.

Lisa Phillips

I first encountered Diego as a fixture of the ’80s East Village scene. He was funny, clever, and very smart. His encyclopedic New York/New Wave became an instant classic. His endless energy, curiosity, and buoyancy propelled him towards new artists, new places, and new adventures. Though his origins and name remained a mystery, he stood for the self-made, self-invented impresario with big ambitions and a confidence to try things that others might have found outlandish. He was always generous with a touch of good natured wickedness lest we took ourselves too seriously.

Lisa Rosen

For Diego…

Just a few weeks ago I was telling someone how you got us into Milton Berle’s 90th birthday party. Around the back entrance of a fancy 5th Avenue apartment building, where the men with the guest list clipboards and walkie-talkies were. I had no idea how we were going to get in … without invitations … You said, “Just be quiet and follow my lead.”

Man with clipboard: “Name, please?”

Without missing a beat you replied, “Rosen.”

He flipped through the names, stopped on a page, looked up, and asked, “Bill Rosen?”

“Yes.”

“Right this way, Sir.”

How did you think of that so damn fast??? That at a Milton Berle party OF COURSE there would be at least one guest named “Rosen”…??!!!

You genius, you!

Liza Béar

TESTING THE PARAMETERS OF ART-MAKING:

A flashback by Liza Béar

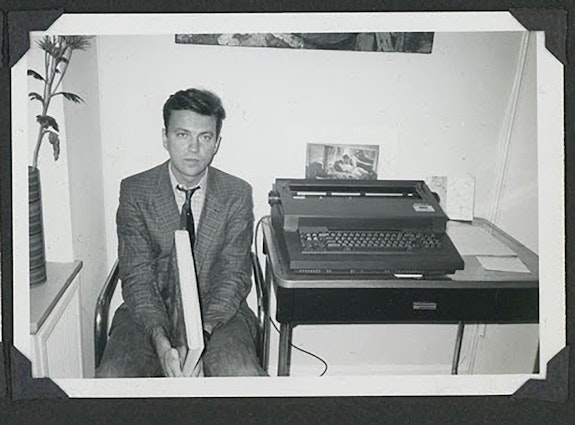

Saturday, April 3, 1976—I’m at Diego’s studio on 308 Mott Street, setting up the microphone on the kitchen stove while Diego packs to go to Europe. The night before, Diego had screened some of his experimental text films like Posture and Poisoning on an analytic projector at Artists Space.

Despite his imminent trip, Diego is not distracted. He stays on point—loose and articulate. The recording has the fluidity of his thought process, laced with wit.

We discuss the origins of the work, influences such as Antonin Artaud, his own attitudes ... he likes the word “peripatetic.” He tells me he has moved as much as three times a year for the last six or seven years, because he doesn’t like to get too anchored.

Among the key concepts that motivate his activities, in and around art, is his model of the artist as a kind of virus, infecting his audience. This was ages before the term “viral” was in common parlance.

Featured in the 13th, Summer 1976 edition, newspaper format—like the later Avalanche interviews, the published dialogue hews close to the raw transcript.

True to form, the interview is provocatively titled with his choice of quote “Diego Cortez: An Obvious Kind of Eyesore.”

I was at first reluctant to post only an excerpt from it, out of loyalty to Diego’s expressed desire to construct his own identity—in the 2000s, he had also wanted his Wiki page purged because he didn’t write it–as well as respect for the Avalanche modus operandi and format. Yet it seems important in this context—a context that is primarily the words of others—that Diego be represented at least in part by his own words. The full interview is at this link; below is an excerpt.

ROLE PLAY (verbatim excerpt : questions are mine)

[Diego]:…The teacher-student thing is one

institutional model that really

bothers me, like the doctor/patient

in medicine. Finding my role ,

playing my role, is the most basic

thing to me: all the films,

installations, anything I do comes

from this role-play—subverting the

idea of artist as …and replacing it

with a doctor/patient model.

---You want the artist’s role to be a

little less grandiose?

---I don’t know anything about

medicine really, so in that way I’m

a kind of quack…

--(uncomfortable laugh) What are

some of the books you have in your

studio? “One Thousand Questions

and Answers”, “How to Remember

Names and Faces”; “Five Things

This Book Will Do For You”…

---That one fits into security, that’s

another role I’m interested in.

---What role?

---The art guard. Because the art

object has a certain value, there has

to be a person who guards it . . .

---Are you interested in

undermining that too?

---Not only . . . I’m interested in

playing that role. I liked what

Shafrazi did with the Guernica, but

I thought it was just as interesting

for me to then get a job as the

guard who guarded that very thing.

---Is that what you did?

---Yeah, within a couple of weeks I

was guarding the Guernica. Because

of the obvious . . . what’s the

word. . .stigma . . .they had to

have one guard stand next to it,

whereas in the other rooms, the

guard could float between two or

three galleries at a time. I had to

stand within three feet of the

Guernica, and not move.

---Did you create this job for

yourself?

---Well, I went after it. I needed

money, and I thought if I had to do

any kind of job, I wanted it to

relate. I wanted it to be

performance, I wanted it to be art.

I was into. . .trying to integrate

those things at the time. And I also

thought I would get a lot of

information from that job to put

into pure art situations.

---Did you?

---None.

FAST FORWARD SEVERAL DECADES

Our Avalanche dialogue is the basis for, the anvil on which unspoken understanding is forged, fellow feeling created... Despite long gaps in—or only incidental—communication over the decades, while our lives took different turns, in 2019 it’s nevertheless a touching surprise to receive the following email, showing Diego’s characteristic humor and generosity.

From my Inbox

On 2/25/19, diego cortez<[email protected]> wrote:

Liza,

What’s this about your staying with me in New

Orleans during Keith’s opening?

That would be lovely.

Diego

When, a couple of weeks later, I arrive at Diego’s renovated shotgun house on Congress Street in Bywater, not far from the Mississippi, he even offers to pay for the cab ride from the airport.

Shocked and saddened at his tragic and painful passing this year, I’m lucky and happy that, for a few vibrant, event-filled days at least, we had the chance to reconnect.

–Liza Béar, New York City, August 2021

PS Diego sent me this photo of his dining room after he had moved his desk there during the summer heat.

Lonnie Holley

When I met Diego it was clear that he was really tuned into the arts and how art and music shaped our culture. I was honored that he took such a deep interest in my art, but more honored that he took an interest in me as a person. I appreciated that he told many people about my art, but I appreciated even more that Diego’s guest room was always available whenever we showed up at his house.

I enjoyed so many conversations and meals with Diego over the years. I will really miss his company.

In his final days, he was heavy on my mind. I was driving south from New York with my friend Matt Arnett, and as we drove through Chapel Hill I asked Matt if he’d heard anything since his visit with Diego a few weeks earlier. He said he was planning on checking in the next day. We heard later that night that he had passed away, and I realized that I was driving just a few miles away from his hospital at the time of his passing.

He had a great brain.

He has finally become a dust speck out in Mother Universe.

Thumbs Up Diego and Mother Universe.

Luigi Ontani

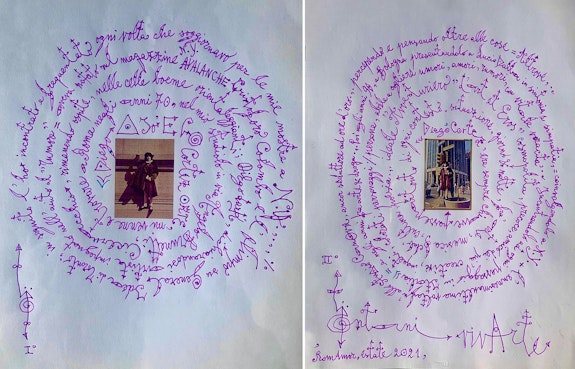

∆iego ∆Io EGO Cortez ORTE

- Diego Cortez came to visit me in Rome in the 70’s, in my small studio in Via Angelo Brunetti, Ciceruacchio, staying as a guest, in the bohemian Oriental-styled cells; DiEgo the Arrow, declaring himself to be artist, engaged in helping the “Tumor” = he noted in the magazine AVALANCHE - Christopher Columbus - Olympus & General Idea of Toronto; then I met him and spent time with him each time I sojourned for my shows in NY.,.,.