Muzo Aiming to Put the Shine Back into Colombian Emeralds

In 1622, the Spanish galleon Nuestra Señora de Atocha, part of an armada of 27 ships headed for Spain, was wrecked off the coast of Florida with the loss of the ship and its cargo of gold, copper, silver, tobacco, and jewels. Although the Spaniards searched for the ship for years, it was not until 1985 that an American treasure hunter finally discovered its resting place and started to salvage its treasures.

Today, one of the rare artefacts recovered, a stunning golden orb topped with a cross and embellished with 36 emeralds, is given pride of place in the private collection of Muzo International. The company is a subsidiary of the Texma Group and was awarded exclusive mining rights in late 2009 to the Muzo mine from which these emeralds are believed to have originated.

Colombian rough emeralds have long been highly prized for their deep green color, but Ronald Ringsrud, a gem expert who has been working for Muzo since 2013 as a director of emerald quality, points out that it is “only fairly recently than geologist have been able to explain the difference between Colombian, Brazilian, and African emeralds. “African and Brazilian emeralds are mainly metamorphic in their origin, coming from higher heat and more pressure, while the Colombian emeralds have developed through hydrothermal fluid moving from deep below, through a softer sedimentary soil... This leads to emeralds that are larger and purer in color,” he argues, adding “If you lay next to each other in the light, a Brazilian, African, and Colombian emerald, they are all beautiful stones, there is no denying, but if you take them away from the light, that’s where you will notice the difference in color. The Colombian emerald still really glows in color.”

Francois Curiel, Christie’s chairman of Asia Pacific, notes that from a market perspective, the Colombian origin of an emerald tends to assure a higher intrinsic value than those from any other geographical provenance: “Thus it is not surprising that of the 20 emeralds that achieved over $100,000 per carat in auction history, 19 hail from Colombian mines. The lone exception is an Afghan emerald of 10.11 carats of exceptional transparency, which went for $225,000 per carat at Christie’s Hong Kong last December.”

Graeme Thompson, director of jewelry at Bonhams Asia, agrees, pointing out the international market deems Colombian emeralds to be the king of emeralds. “They are the most highly prized for their classic, fine blueish-green hue and vivid saturation which is typical of the Muzo and Chivor mines. The most highly sought after emeralds are old mine material which date back 50 years and more.”

However, he also points out that though gem quality Brazilian emeralds are less abundant than their Colombian counterparts, fine examples can also command impressive prices at auctions as they are known for their lack of inclusions and high purity.

“In the last two years emerald prices have seen the biggest increases when compared to other colored gemstones, particularly when there is little or no oiling in the stone. There is no evidence to suggest that this momentum is slowing, particularly for old mine material which, more often than not, has exceptional characteristics,” Thompson says.

Amongst the Colombian mines, the Muzo mine, about 100 kilometers (60 miles) north of Bogotá, is one of the most famous and was already being exploited by the indigenous population when the first Spanish conquistadors arrived in the 16th century. This is where the largest rough stone, the Fura Emerald weighing 2.27 kg, was found, and the mine currently exports $100–200 million worth of emeralds every year, according to Ringsrud, who worked for many years as a private dealer in emeralds and has authored "Emeralds, A Passionate Guide."

Though Muzo had mining rights it wasn’t until 2013 that it gained full control of its mine, when the previous owner, Victor Carranza, dubbed in the Colombian press the “emerald Czar,” passed away. Elizabeth Robinson, CEO of Muzo International, says getting control enabled the company to offer full transparency on its operations. “We’re able to show customers an entire history from the moment the stone is pulled from the ground to the final faceting, and we can also demonstrate that our emeralds are responsibly sourced. And in today’s world, we believe there is value in that,” she says.

From the moment it gained control, Muzo set about modernizing the mine, and announced it would improve safety practices and labor practices, for the first time paying the miners. It has also invested in training programs at the company’s cutting atelier in Bogotá. Emeralds are particularly hard to cut, because they are more brittle than some other gems and can also have significant fractures that will need to be minimized through expert cutting to enhance the finished stone. Ringsrud says that on average 60-70% of the stone’s weight can be lost to create a faceted stone. “We’ve made very subtle changes in cutting techniques, but these can make a huge difference in how the light is reflected in the stone,” Robinson says.

Now, the company is ready to focus attention on its sales side, and in branding its gems 'Muzo emeralds,' it will guarantee their provenance to retail buyers through detailed documentation and a certificate of origin.

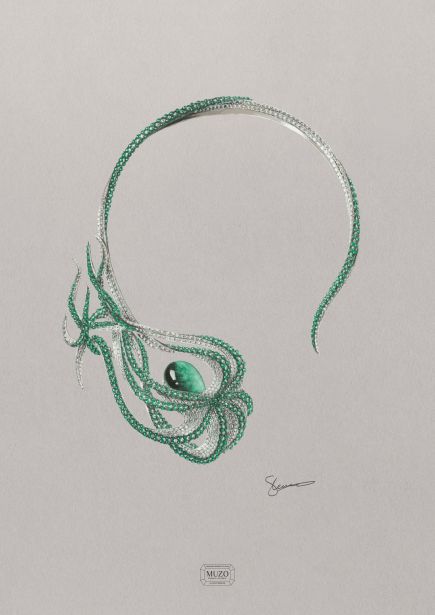

To illustrate the creative potential of the stones, the company will present several jewelry pieces at Baselworld that had been designed by renowned international jewelry designers — Antoine Sandoz, Studio Naio, Elie Top, Shaun Leane, and Solange Azagury-Partridge. These unique pieces will then be shown at Couture Show Las Vegas in May, together with the historic collection of Colombian treasures recovered from the Nuestra Señora de Atocha shipwreck.

“We want to show with these new jewelry pieces what can be done and inspire creators to use our stones and to showcase the work we’ve done and the improvement on our cutting,” Robinson says.

Her dream: when a customer no longer demands a Colombian emerald, but a Muzo emerald!

as first published in Blouin Lifestyle Magazine