Warner Hollywood Theatre

When it became apparent in the early 1920s that Hollywood Boulevard would become the primary commercial and entertainment center for the town’s burgeoning film industry, one of the first orders of business was to create retail outlets for the industry’s main product: its movies. Within the Hollywood Boulevard Commercial and Entertainment District are a concentration of entertainment-oriented structures, employing a variety of styles, and significant as a group, both functionally and architecturally. This cluster of theaters on Hollywood Blvd, legitimate and cinematic alike, made the thoroughfare a popular destination for the surrounding communities, creating an aura of fantasy for residents of the area and a draw for tourists as well.

As part of establishing their brand, each of the studios wanted its own venue. The Warner Brothers were no exception. As they watched Sid Grauman’s affiliation with Paramount, Fox and United Artists grow, first at his Egyptian Theatre in 1922 and again at the Chinese Theatre in 1927, they also thought it wise to carve out land in the middle stretch of the Boulevard for their own “movie palace”, an elaborate four story business block on the northeast corner of Hollywood Blvd (6423) and Wilcox Ave.

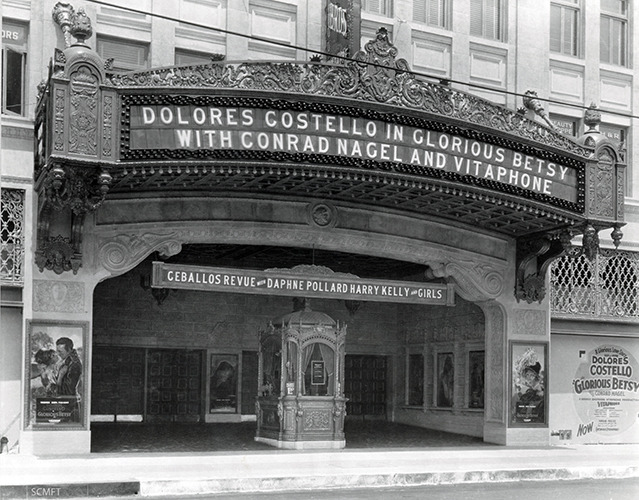

To compete with the flamboyant “programmatic” architecture of Grauman’s Egyptian and Chinese, they chose an ornate construct of Spanish Colonial Revival style known as “Churrigueresque” which had its roots in the Spanish Renaissance. They hired well-known architect G. Albert Landsburgh, who already had a reputation for his stylish interior designs at the Shrine Auditorium and the El Capitan Theater. Their planning and well-publicized advertising campaign began in 1925, just before the groundbreaking of the Chinese. The Warner Brothers vowed to build “The World’s Most Beautiful Cinema” in an effort to reinforce the concept of Hollywood as the movie capital of the world.

The massing of the business block, while horizontal, shares similar decorative elements with the El Capitan. Elaborate detailing is evident on both the south and west facades. The classic facades are very symmetrical, with window bays placed between ornate vertical pilasters. Built of reinforced concrete embellished with concrete ornament, the building retains its original grill work above the shopfronts on the street level. The main entrance was dominated by an oversized marquee which jutted from the building. The original has now been replaced, but much of the detailed entrance, lobby, and interior remain. An elaborately ornamented arcade runs along the west façade. Medallions, gargoyles, Spanish conquistadores and cast floral ornament are characteristic of the style and feature prominently on the Hollywood and Wilcox facades. The entry’s ornate carved ceiling is another prominent feature.

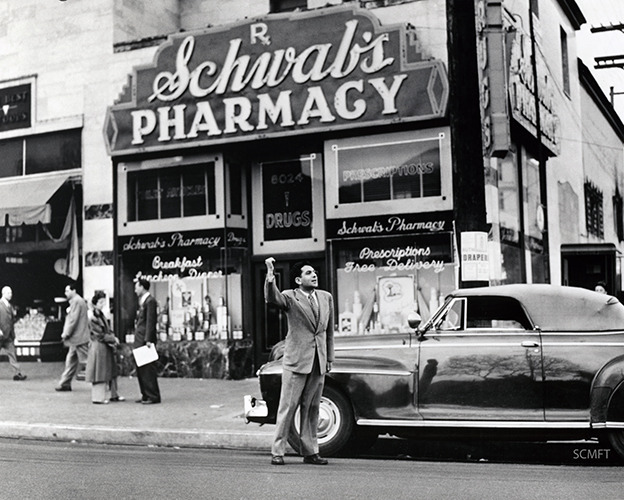

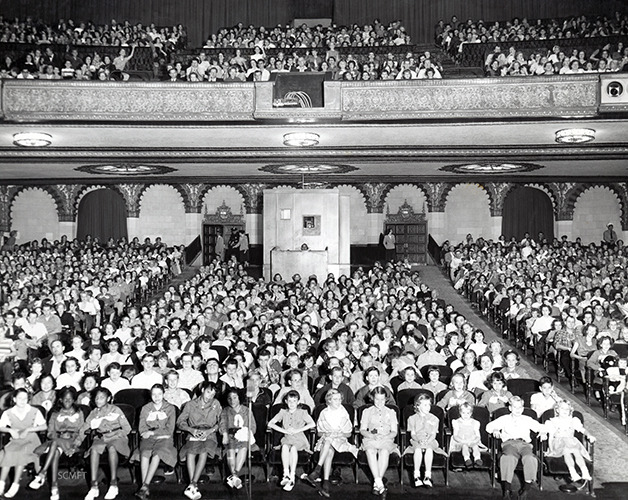

Through the lobby entry, an elegantly appointed auditorium with a large balcony greeted audiences. Great care was taken to provide every comfort and convenience to patrons. After 14 months of construction, the 2700 seat theater (then largest on the Boulevard) opened with much fanfare on April 26, 1928 with the premiere of Glorious Betsy starring Delores Costello and Conrad Nagle. From the start, this was a “talkies” venue, with the use of the Warner’s Vitaphone sound system. Like the Egyptian and the Chinese, a massive organ also was installed. The Warner Brothers were pioneers of radio broadcasting as well and thus incorporated two signature radio towers of their KFWB station on the roof. The towers were first used in 1929.

The theater was repeatedly adapted to new technologies over the years. The original proscenium was lost in the conversion to Cinerama in 1953; further changes accommodated 70mm screenings in 1961. In 1978, the balcony was divided into two smaller theaters.

Like many of the buildings on Hollywood Boulevard, the Warner has played a supporting role in many films, including Ed Wood (1994), and most recently The Nice Guys and Hail Caesar (2016). Closed as a full-time cinema in August 1994, the Hollywood community eagerly looks forward to a rehabilitation and re-use of The Warner Theatre in keeping with the successful reinventions of the neighboring Egyptian, Chinese, and Pantages.

~ Christy McAvoy, Historic Hollywood Photographs

Sources: Bruce Torrence archives; losangelestheaterblogspot.com