by Paul R. Spitzzeri

The oil industry in greater Los Angeles had its modest origins in 1865 when the Pioneer Oil Company drilled in Pico Canyon in modern Santa Clarita, just six years after the first American well was completed in Pennsylvania. Within a decade, the area, known as the San Fernando field, was a hive of prospecting activity, including F.P.F. Temple’s Los Angeles Petroleum Refining Company and Lesina Oil Company and he was able to generate some crude from one of his wells while being the state’s first steam-powered refinery, albeit a simple operation.

The early 1876 failure of the Temple and Workman bank ended Temple’s early endeavors in the industry, though four decades later, his son, made an astounding entre into the oil world through a stunning discovery of oil on Montebello Hills land owned by his father until the bank debacle and taken over by Elias J. “Lucky” Baldwin, who foreclosed on a loan to the institution and took possession of the property. After Baldwin’s 1909 death, Temple struck a deal with executor Hiram A. Unruh to acquire sixty acres there, even though he had to essentially borrow the money from the estate and pay on installments. When oil was brought in in sumeer 1917 and several gushers developed over enusing years, Temple parlayed his royalties into his oil prospecting business, though it was a small enterprise compared to the big boys.

Meanwhile, in mid-1876, just months after F.P.F. Temple’s financial failure, Star Oil Company brought in a major well in the San Fernando field. A decade later, former sheriff and Rancho La Puente heir, William R. Rowland, and his partner William Lacy found abundant oil in the Puente Hills in modern Rowland Heights. Charles Canfield and Edward Doheny, fresh from mining work in New Mexico, came to Los Angeles in the early Nineties and, with a crude (!) apparatus, opened the Los Angeles City oil field, By the end of the decade, Doheny inaugurated Orange County’s first field at the Olinda Ranch in today’s Brea.

In the 1880s, at Santa Paula in Ventura County, Lyman Stewart and Wallace Hardison maintained an informal relationship with Thomas Bard, who had a pair of oil companies, but suggested the three team up, leading to the October 1890 creation of the Union Oil Company of California. Hardison later bowed out and differing philosophies caused a rift between Bard and Stewart, with the former taking a more conservative stance, but the latter winning out with his ambitions, but risky, ideas and taking control of the company by mid-decade. Bard left as the new century dawned and Stewart moved the headquarters to Los Angeles.

Stewart wanted to not just produce and sell wholesale crude, he wanted to refine, market, and sell gasoline and oil products and the company inaugurated a host of innovations (its own geology department, an early oil tanker, cementing wells, and its own service stations), but the firm lacked sufficient cash reserves as Stewart bought enormous land holdings, racked up a great deal of interest payments on bonds, and borrowed liberally from banks and financial houses. In 1914, Stewart was forced to resign and his more conservative son, William, took over.

Under William’s leadership, Union continued its rapid growth, but, in the early Twenties, Royal Dutch/Shell initiated a hostile takeover attempt. Lyman Stewart, still chair of the board of directors, worked with prominent banker Henry M. Robinson and Isaac Milbank, former executive of the Borden milk company, to form Union Oil Associates to buy up company stock and stave off Shell’s maneuvering. The gambit succeeded, soon after which Lyman Stewart died, leaving Robinson as president of the associates group, while Shell sold its stock on the market. During the remainder of the decade, Union’s financial condition was solidified and growth continued apace.

Today’s featured object from the Homestead’s collection is the “Annual Report of the Union Oil Company of California” for the fiscal year ending on the last day of 1928. The report is dated 7 February and there is an accompanying letter, dated two days later, to shareholders from Union Oil Associates and signed by Robinson. The missive noted that, aside from just a little over $1,000 for office furniture and some cash in the bank, the assets of the Associates comprised of over 2.1 million shares of Union stock. There was a modest debt of some $40,000 “for borrowed money and current liabilities.”

Robinson added that the company had just below 10% of its property and assets outside California and its stock was assessed at just north of $850,000 and paid just south of $34,000 in taxes on that value. This fixed charge varied from year to year depending on how much of the company’s assets remained out-of-state, but “the tax paid by Union Oil Associates direct to the Assessor of Los Angeles County thereby relieves the stockholders of Union Oil Associates in California from paying a personal property tax on their holdings.” Finally, a two-cent per share deduction from the divident payable on that date “will pay the liabilities of your Company and leave a working balance.”

The report’s first page listed the board, including Stewart and his namesake son, who later was the longtime chair, Robinson, Edward W. Clark (formerly assistant treasurer,) prominent oil geologist William W. Orcutt, and Press St. Clair, who succeeded to the presidency after Stewart died in 1930; the executive committee of nine of the eighteen directos; and the executive officers under Stewart, including Clark as the executive vice-president, and Orcutt, St. Clair and two others as vice-presidents (one, Robert D. Matthews was the longtime comptroller.)

As to the report, the general summary showed that income rose very modestly, about $280,000, to just shy of $26 million, from the prior year, though there was a drop of over $700,000 in general expenses, taxes and the provident, or retirement, fund for employees, offset with just above $50,000 in net interest charges, while there was also a small increase of about $110,000 in depreciation, depletion and expenses for drilling. In all, profit was just above $11 million, an increase of some 10% from 1927. Per share, this came out to $2.92, whereas it was $2.65 in the prior year.

The report noted that “profits during the latter part of the year 1928 were unfavorably affected by the increase in refining crude oil prices in August without any increase in the realization from the sale of products” as well as labor and development costs on 300 acres “in the Santa Fe Spring Field to protect the Company’s acreage from drainage by adjoining wells.” Union also sold property in Colorado and Wyoming, though that profit “has been almost completely offset by reducing the inventory value of our fuel oil stocks.”

The general charge decline was because of lower income taxes and it was reported that about $1.65 million was paid to state, county and city taxes, while over $5.7 million went to states and Canadian provinces for gas sales taxes. The retirement plan contribution was $473,000, a drop from almost $508,000 in 1927.

Production of oil and gasoline, including from wells in Colorado, Wyoming and Texas was over 13.7 million barrels for 1928, a 10% decline from the previous year, but production averages for the over 600 wells on the pump went up from about 46,000 per day at the beginning of 1929 to some 56,000 by the time the report was produced. There were 166 wells offline, but with a capacity of some 11,500 barrels per day, while the firm bought some 70,000 barrels each day.

In all, California production and purchases went up over 9% to almost 40 million barrels for the year and production jumped some 1.2 million barrels above the 1927 output, “the total being exceeded only by the record year of 1923.” Much of this was attributed to deeper drilling at the prodigious Santa Fe Springs field. It was reported that the state’s total production for 1928 was almost 246 million barrels, including crude and natural gasoline, the latter comprising abou 14 million. There were forty-two drilling crews at work, some 80% in southern fields and a scattering in the San Joaquin Valley, Ventura, Santa Maria, Texas, Mexico and Venezuela.

One test area in the San Joaquin was at the “San Emidio Ranch,” once owned by F.P.F. Temple and David W. Alexander, a close friend of the Workman and Temple families. Another new area of exploration was on 6,400 acres near the mouth of the Columbia River in Washington and the inaugural well on a 26,000-acre lease in Veracruz, Mexico and a second attempt at a joint project in Venezuela were underway.

Company sales totaled over $85.3 million for the year, an increase of about 6% or $5 million for the previous year, including refined and lubricating oils, fuel and gas oils and asphalt and it was observed that “the year reflected further development in our refined oil export cargo business.” Property values totaled about $284 million, including $18 million expended and over $8 million in property sold and relinquished, wells abandoned and others that were written off. Total acreage owned was just over 600,000 acres, with another 88,000 under lease. Of this, just under 30% was in California, while almost 60% was in Colombia with much smaller amounts in Washington, shale lands in Colorado, Texas and Mexico. Union held a minority interest in some 400,000 acres in Texas and a half-share in 880,000 Venezeuela lands mentioned above.

New drilling costs were over $7.6 million and there was about $5.8 million charges against income for drilling expenses, abandoning of wells, well and equipment depreciation and so on. Total oil well and development amounts was above $13 million for 782 wells that were producers or temporarily offline, 171 that were drilling or not active and other facility amounts. About $2.3 million was involved in pipelines and storage, with most of this comprising the firm’s Torrance refinery, including a 4 million barrel capacity reservoir and twenty-one tanks of 100,000 barrel limits, on just shy of 100 acres, with another twenty-two acres and two tanks at nearby Watson near Wilmington. There were aso costs for rehabbing reservoirsat San Luis Obispo and general pipeline work.

As of the end of 1928, Union had a total storage capacity for crude and refined oil of about 35 million barrels and owned over 500 miles of trunk and 360 miles of gathering pipelines, with a capacity in these of some 245,000 barrels. The firm owned a dozen steamship tankers and over twenty barges and othe craft, with capacities of 900,000 barrels. Nearly $2.2 million was spent at efineries, absorption plants and gas facilities, most of it for various portions of the main Los Angeles refinery, though there was work done at Oleum (get it?) on San Pablo Bay north of Berkeley, the Maltha refinery in northeast Bakersfield, and at other sites. Total refinery output was 115,000 barrels per day.

Fo marketing stations, almost $4.4 million was expended, including over thirty distribution station and forty-four service stations. More than 200 cars, nearly 70 trucks, a quartet of airplanes and a motorship with 10,000 barrel capacity and use in Canadian wates er acquire. In all, the company possessed almost 400 sales stations, over 450 service sations, and had nearly 1,100 cars, 1,200 trucks, 675 tank cars for trains and those new aircraft. There was also the 1927 organization of the Atlantic Union Oil Company, a project with Atlantic Refining, for selling petroleum products in Australia and New Zealand with terminals, costing over $4 million including vehicles and 250 sales depots, completed at Melbourne and Syndey in the former and Auckland and Wellington at the latter. Retail distribution had been in place for some eight months to date.

Current assets were just shy of $57 million with a five-to-one ratio related to liabilities, though this latter increased over $1.8 million while assets declined by nearly $1 million in 1928. Cash and bonds totaled over $13 million, just about the level of accounts and bills receivable, :which is considered adequate to cover possible losses.” Total crude and refined oil inventories were almost 25.7 million barrels and, at just over a dollar a barrel (prices dropped 19 cents during the year), the value was nearly $27 million and there was an increase of almost 4 million barrels from 1927. Another $3.4 million was valued for materiel and supplies.

Outstanding stock increased with the issuing of over 3,100 shares to over 300 employees by terms of an offer from mid-July 1925 and the amount was just above $78,000. Nearly 5,000 shares were subscribed for, but not issued to almost 370 employees under that arrangement. Total shares outstanding was almost 3.8 million, with about 6,700 shareholders having an average of below 250 shares a piece. Union Oil Associates numbered over 3,800 persons and their average holding was about 560 shares with that entity owning not quite 60% of the stock. At the end of 1928, a new issue was made to bring the total to almost 4.2 million shares and raising over $13 million for Union, by which shareholders could take one new share for each ten held or subscribed at a value of $35 each (paid in cash or by quarterly installments during 1929.)

As to liabilities, retired debt was almost $2.7 million, though the company deducted about $650,000 of its own bonds and there were purchase obligations and current liabilities of over $3.3 million, with about $1.5 million in five-percent bonds substracted for a net increase of about $1.9 million in total liabilities. The balance surplus from 1927 was just south of $20 million, so the 1928 profit of $11 million and the deduction of $7.6 million in dividends (50 cents per share quarterly) paid out and a small sum for the value of bonds and cancelled premiums for employee stock subscriptions left some $23.2 million in surplus. Another $41 million in the value of proven oil lands left a total surplus of above $64 million.

Naturally, these reports can get very numbers-heavy, so a condensed summary was provided “in the form which it is believed will briefly convey the clearest statement of results.” Namely, there was profit before depreciation of almost $22 million. Factoring in a decrease in investments and in cash, inventory and receivables of not quite a million dollars and the liability increase of about $1.9 noted above, there were about $3.2 million involved and a miscellaneous about of under a half million. Offsetting these were property additions of almost $18 million and the paid cash dividends of over $7.5 million.

It was noted that in the nearly three decades since dividends were paid, that amount was almost $90 million, while stock, at par, distributions were another $60 million, the aggregate being about 13% per year of outstanding stock. There was another $63 million in surplus, amounting to about 5.5% of the stock. Payroll totaled $19 million, a slight increase over 1927, with almost 10,000 employees, a growth of about 1,000. About half, or over 80% of those eligible, were enrolled in the retirement plan, this also a slight increase from the prior year and the fund’s value was over $5.3 million. Moreover, there were over 6,400 employees in the benefit fund plan with over $9.5 million in it, while another 5,600 took out over $12 million in life insurance.

In its concluding statement, the report noted that, in 1928, Pacific Coast fuel oil inventories increased by some 6 million barrels, while refining crude and gasoline stocks dropped by some 2.4 million. Gasoline output in California leapt by 6 million barrels over 1927 levels. December 1928 productin from almost 11,000 wells totaled almost 700,000 barrels, about the same production from 9,400 wells five years before. Prices increased just one cent per barrel for gravity of 20 degrees or higher, but plummeted as much as thirty cents for lower-gravity crude.

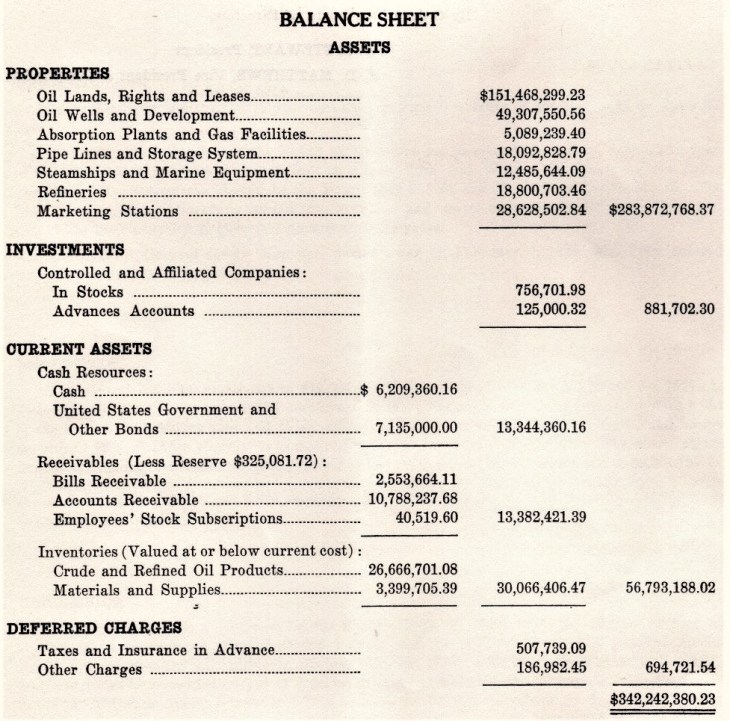

Finally, the balance sheet showed total assets of over $342 million, over 80% of that in properties of several kinds. Current assets of cash, receivables (about $13.3 million each) and $30 million in inventories, totaled about $57 million. Liabilities involved some $95 million in stock, $148 million in reserves, $24 million in mortgage debt (mostly bonds with $2 million in purchase obligations), $11.5 million in accounts payable, reserves for taxes, and accured interest, and the $64 million in surplus. A note included the assumption that over $13 million would be raised from the aforementioned late December stock issue.

By any measure, the financial position of Union was solid, though it should be noted that, eight months after the report was issued the stock market crash in New York brought the beginnings of the Great Depression. Press St. Clair took over in 1930 after William Stewart, Sr.’s death and a landmark in marketing took place two years later when Robert Matthews, a native of England but studying for his citizenship test, noted that Union’s highest octane fuel level was 76 and combined that with the revolutionary year 1776 for the “Union 76” brand name for its gasoline.

After St. Clair retired in the late Thirties, new president Reese Taylor controlled the firm for almost a quarter century, but Union remained largely a regional company, relying on California wells for most of its output, while other companies expanded worldwide. There were later threats to its independence from such giants as Gulf and Phillips and some attempts to expand in order to survive by the late Sixties. A disastrous 1969 oil spill off the coast at Santa Barbara hurt Union’s reputation considerably, but it moved into liquified natural gas, geothermal exploration, and shale processing. In 1983, it reincorporated as Unocal Corporation in Delaware to stave off hostile takeovers, though T. Boone Pickens tried without success, though it amounted to large accumulated debt in stock buybacks to beat back the corporate raider.

In the 1990s, Unocal ended its California production efforts, while expanding overseas, especially in Asia, though its efforts in politically corrupt or unstable nations, economic uncertainties, and production problems. It weathered much of these storms and remained profitable when it was purchased by Chevron Texaco (Chevron being the former Standard Oil Company of California, which produced on the Montebello Hills lease of Walter P. Temple from 1917 onward) for some $17 billion, ending 115 years of independent operation.