THE QATAR GUIDE

ART, CULTURE, HERITAGE

A–Z OF QATARI CULTURE

These are words, terms, concepts, and pillars of Qatari life and culture that a visitor to the country might encounter

Abaya

This is the flowing robe worn by women, loosely fitted over everyday clothes. It has long sleeves and goes down to the feet, so the body is fully covered. It is usually black. It’s worn with a scarf around the head so no hair shows. Modest doesn’t have to mean drab: designers have taken the robe to a whole new level, to the extent it now features in international haute couture events. The abaya can be as much an expression of individualism as any dress.

Arabian horses

Long before Qatar became one of the world’s fastest growing economies, it was revered for its horses, especially the Arabian breed. They are distinguished by a comparatively small head with a slight dish below large dark eyes, a finely arched neck, a tail held high, and a floating gait. In Al Shaqab, in Doha, the country has a state-ofthe-art equestrian center, established to build on Qatar’s Arabian horse heritage and to help preserve and perpetuate the breed.

Ardha

In Qatar men dance with swords to the beat of tribal drums. It’s known as the ardha and has its origins among the Bedouin tribes that used to predominate on the peninsula. Originally a war dance, designed to get the blood up before combat, these days it’s usually performed in less confrontational circumstances, such as weddings, during the Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha holidays, and also on Qatar National Day.

Battoulah

A battoulah is a mask that used to be worn by women for modesty— and to protect their faces from the sun. It is made of leather or cloth with a central strip that runs down the nose and ends in a flared tip, said to mimic a falcon’s beak. Some battoulahs are golden in colour because, it is said, this reflects the rays of the sun. Few Qatari women wear battoulahs these days, but they are often referenced as a significant element of national heritage.

Blockade

On June 5, 2017, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Egypt abruptly severed diplomatic ties with Qatar over disagreements on foreign policy. All cross-border routes were closed, Qatar was isolated, and severe diplomatic

restrictions were imposed. The blockading countries set conditions to lift the siege, but Qatar considered these a violation of its sovereignty. The blockade caused many injustices, including the separation of families. Qatar responded with legal proceedings. The crisis ended in January 2021 following a resolution between Saudi Arabia and Qatar.

Dhow

These are the traditional Arab sailing vessels, with one, or sometimes two, slanting triangular sails. Historically, the dhow was the main vessel for fishing, pearling, and seaborne trade across the Indian Ocean. An annual dhow festival, inspired by the country’s maritime heritage, takes place at Katara every winter. One of the most pleasurable things to do in Doha is take a dhow excursion at sunset.

Falcons

Falcons are strongly associated with Bedouin life. In the past, trained birds hunted and brought back small prey that supplemented people’s sparse diet. These days falconry is a recreational activity and part of a living cultural heritage. Falcon owners and enthusiasts head to the desert at weekends to watch the raptors hunt. A section of Souq Waqif is dedicated to the sale and care of falcons. There is also a falcon society in Katara, shaped like the hood that owners place over the birds’ heads to keep them calm.

Father Amir

This is the term of respect often heard when someone is referring to Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, the ruling Amir of Qatar from 1995 until 2013, when he abdicated the throne, handing power to his son Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani. Sheikh Hamad is considered the architect of Qatar’s modern revival. During his reign, he oversaw massive economic, social, and cultural development, while the State of Qatar cemented its global status.

Flag

Traditionally, the tribes of the Arabian Gulf raised red flags. However, when the Qatari tribes were first united the banner under which they gathered was maroon. In the 1930s, the British Navy tried to introduce a flag for Qatar with a red background and a white band with nine points, representing Qatar as the ninth signatory of British treaties. Qatar replaced the red with maroon and added white diamonds to the white band, as well as the name Qatar written in white. In 1960, Sheikh Ali bin Abdullah Al Thani simplified the design and, in 2012, the Father Amir Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani issued a law specifying the design for the flag, which is called al adaam.

Islam

The state religion of Qatar is Islam. Although the country is not an Islamic theocracy like its neighbors Iran and Saudi Arabia, where clerics are part of the ruling apparatus, Qataris are religious. Mosques are low key and tend not to dominate the skyline as they do in many other

Muslim countries, but the five-times-a-day call to prayer provides a soundtrack to daily life. Everything shuts for Friday prayers, the sale of alcohol and pork is limited, people dress modestly, and fasting during the month of Ramadan is strictly observed, as are other Islamic holidays.

Al Jazeera

The first independent news channel in the Arab world, Al Jazeera launched from Doha on Friday November 1, 1996. The channel’s founding tagline was “The Opinion and the Other Opinion” because it aimed to present multiple angles to every story, informing and empowering its audiences, while maintaining the spirit of journalistic integrity. Al Jazeera is now one of the largest and most influential international news networks in the world, with over 70 bureaus around the globe, staffed by more than 3,000 employees from in excess of 95 countries. The station is emblematic of the role the Qatari nation sees for itself as a facilitator of global dialogue.

Machboos

If Qatar can be said to have a national dish, then it’s machboos This is a base of spiced-rice— spices typically used are cinnamon, cardamom, cumin, and turmeric— topped by marinated chicken, or sometimes lamb or seafood. For more on Qatari cuisine, see pXXX.

Majlis

The majlis (plural majalis) is the social center of male life in Qatar. It is the “sitting place” where men gather to talk. The majlis can be a room in a family home, a tent in the desert, or a larger, more public space in which the community gathers to resolve problems, pay condolences, and hold wedding receptions. In all cases, it typically has carpets on the floor, cushions against the wall, and some sort of stove or fire for the preparation of coffee. The majlis plays an important role in the transfer, between tribes and generations, of knowledge and oral heritage, including folk stories, and poetry.

Multiculturalism

Qatar is one of the most multicultural societies in the world. Qataris are a minority in their own country, representing only around 12 per cent of the population. The remaining approximately 88 per cent is made up of a migrant workforce of close to 100 different nationalities. Indians (approximately 650,000 in number), Nepalis (350,000), and Bangladeshis (280,000) are the most represented nationalities in Qatar, together accounting for over 50 per cent of the population.

National Vision 2030

Qatar is working toward fulfilling a National Vision 2030, which defines the long-term goals for the country

and provides a framework for the future. The aim is that by the end of the decade the nation is an advanced society capable of sustaining its development and providing a high standard of living for its people.

The National Vision addresses five major challenges facing Qatar: modernization and preservation of traditions; the needs of the current generation and of future generations; managed growth and uncontrolled expansion; the size and quality of the expatriate labor force and the selected path of development; economic growth, social development, and the successful management of the environment.

One Pass

The One Pass is a Qatar Museums initiative: it is a cultural discount card offered at four levels (Silver, Gold, Platinum, Diamond). It allows free access to Doha’s four major museums, numerous exhibitions, and, in the case of the three upper tiers, discounts on dining, and lifestyle and adventure activities.

Pearls

Historically, the Qatari economy was based around pearl diving. The pearls harvested from the waters of the Arabian Gulf were prized for their brilliant luster and luminosity, and were sold to India, Europe, and the US. By the 1930s it was all over (for more on this, see the History section), but the rich heritage of the pearling industry remains woven into the fabric of the nation, from the giant Pearl Monument on Doha Corniche to the pearl-like tiling in Doha’s metro stations.

Qahwa

Doha has no shortage of third-wave coffee shops, offering everything from cold drip to a hot Kyoto latte. But in Qatar, you can also drink the original Arabic coffee, or qahwa—pronounced “gahwa.” It is an aromatic, gold-hued beverage made from green coffee beans, with a perfumed taste that is nothing like coffee elsewhere. It is traditionally served with dates (kholas), which provide a toffee-sweetness to balance the slight bitterness of the coffee.

Qatar Creates

Qatar Creates (QC) curates, celebrates, and promotes cultural activities within the country. Working with partners in museums, film, fashion, hospitality, cultural heritage, performing arts, and the private sector, its aim is to amplify the voice of the nation’s creative industries. It highlights talent in Qatar, and nurtures the ecosystem for the creative economy to flourish.

Qatar Museums

Established in 2006, Qatar Museums (QM) is the nation’s pre-eminent institution for arts and culture. It provides authentic and inspiring cultural experiences through a growing network of museums, galleries, heritage sites, festivals, art installations, and programs. QM preserves, restores, and expands the country’s cultural offerings and historical sites, sharing arts and culture from Qatar and the region with the rest of the world, and enriching the lives of citizens, residents, and visitors by bringing international art and culture to Qatar.

Sadu

You’ll see them all over Qatar: beautiful woven rugs and textiles patterned in a lengthwise set of stripes and vibrant geometric designs, predominantly in black, white, and red. This is traditional Qatari Bedouin weaving, done using a ground loom, and it is known as sadu. Historically, the woven fabric was used for the different parts of a tent. This rare style of weaving was added to UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list in 2020 to prevent the tradition from dying out.

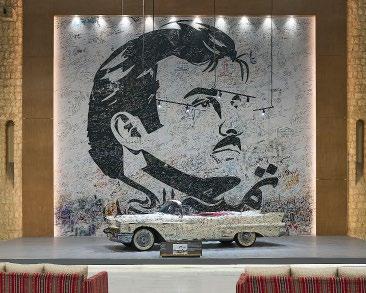

Tamim Al Majd

On wall and buildings across Qatar you’ll see a stenciled image of a youthful man with sweptback hair, mustache, and a resolute expression: this is Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al-Thani, ruler of Qatar, as depicted by street artist Ahmed Al Maadheed. He created the image immediately after Saudi Arabia announced sanctions against Qatar in 2017 and posted it on his social media feeds. The text underneath reads, “Tamim the Glorious”.

Thobe

This is the white ankle-length garment worn by nearly all Qatari men. It has pious connotations and is cool under the searing Gulf heat, but, most of all, it is a symbol of national identity. Some men also wear the gutra, a square piece of cloth acting as a headdress and held in place by a black rope band known as an agal Thobes can be bought off the peg in shops, but it’s also common to have them made to order by tailors, who offer a range of fabrics and collar styles.

Years of Culture

Launched in 2012, after Qatar won the right to host the FIFA World Cup 2022™, the Years of Culture (YOC) is a cultural diplomacy exchange that deepens understanding between the country and other nations. It is a way to introduce Qatar to the world, and the world to Qatar. The festivities last beyond the formal year of cultural programming. In 2024, the Year of Culture will be dedicated to collaborations with Morocco. For more information, see https://yearsofculture.qa/.

ART

Qatar’s contemporary art scene flourishes with both local talent and a roster of international guests

At the time of writing, Qatar’s main art museum is Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art (see pXXX), which holds the finest collection of modern and contemporary Arab art in the world. This will be joined in the coming years by a new institution devoted to Orientalism (see pXXX), and a world-class museum of international modern and contemporary art, to be housed in a conversion of a flour mill (see pXXX). In the meantime, several public galleries hold regular temporary exhibitions of both local artists and internationally renowned figures—see the Museums & Galleries section.

Public art has been part of the urban fabric of Qatar since the 1980s. Originally, it was sited at the center of traffic roundabouts, and was often designed and even made by the people who lived in the neighborhood. The roundabouts had names related to the art: Arch

Roundabout, Water Jar Roundabout, Oryx Roundabout, and so on. These days Qatar Museums (QM) has a dedicated department responsible for curating, commissioning, and installing public art all over Doha and across Qatar. Artists chosen for the program are a mix of local and the internationally renowned. Most visitors arriving in the country are probably here for only a matter of minutes before being exposed to public art, because there are no fewer than 18 pieces dotted around Hamad International Airport (HIA).

Since 2020, the public art has been supplemented by Jedariart, a local mural program. For its first edition, QM commissioned more than 15 artists to paint walls across the city. In 2021, five local practitioners were sent to the US as part of the Qatar–USA Year of Culture. The same year, QM held Pow!Wow!, an international street art festival, and invited local, regional, and

international artists to participate in creating murals that can still be seen in the area around Al Sadd metro station. More recently, two large-scale murals inspired by the popular truck art of South Asia have been completed on walls next to Mansoura metro station.

PUBLIC ART IN QATAR

Hamad International Airport

Adel Abdessemed (b.1971; Algeria) Mappemonde (2014)

Abdessemed is best known for his life-size and larger-than-life-size sculptural representations of iconic images, such as the naked young girl running away from an explosion in the Vietnam War and the French footballer Zinedine Zidane headbutting an Italian player during the FIFA World Cup 2006 final. His Mappemonde is a world map using old tin cans collected in Dakar. It calls for social and ecological awareness and is a critique of consumerism. Located at concourse A, near gate A7.

Anonymous

Charioteer of Delphi

This replica of an Ancient Greek bronze statue, commissioned to commemorate a victory at the Pythian Games, was presented to Qatar by the Hellenic Republic as a symbol of the strong ties between Greece and Qatar through art and culture. Located in the Hamad International Airport metro station.

Dia Azzawi (b.1939; Iraq)

Flying Man, A and B (2016)

These two sculptures, both titled Flying Man, commemorate early attempts of flight in the Muslim world, notably by the 9th-century Andalusian pioneer Abbas ibn Firnas. His experiments failed, but he was inspired by the same spirit

10 MUST-SEE WORKS OF ART

East-West/West-East

by Richard SerraA breathtaking sculpture in a desert landscape spanning over half a mile and comprising four towering steel monoliths. See pXXX.

Falcon by Tom Claassen

Sitting on a ledge facing Hamad International Airport’s departures hall, the Dutch artist’s big golden bird bids farewell to travelers. See pXXX.

A Family Reunion by Abdulaziz Yousef

A much-loved piece of street art by a celebrated local illustrator and cartoonist that depicts the Qatari tradition of extended generation-spanning family gatherings. See pXXX.

Lamp/Bear by Urs Fischer

Dominating the central hall at Hamad International Airport, this giant canary-yellow teddy bear humanizes the space around it and serves to remind travelers of childhood or precious objects from home. See pXXX.

Maman by Louise Bourgeois

Through marble, bronze, and stainless steel, Bourgeois reveals the beauty in the initially terrifying form of a spindly-legged giant spider. See pXXX.

The Miraculous Journey by Damien Hirst

The beauty of the extraordinary human reproductive process, depicted in 14 monumental bronze sculptures, from conception to birth. See pXXX.

Le Pouce by César Baldaccini

This oversized polished-bronze cast of the artist’s own thumb has become a prominent and much-loved landmark in Souq Waqif. See pXXX.

The Repair from Occident to Extra-Occidental Cultures

byKader Attia

Hundreds of objects gathered in one room explore different attitudes toward repair found in Western and non-Western cultures. See pXXX.

Shadows Travelling on the Sea of the Day by Olafur Eliasson

This site-specific installation located in the desert just north of Al Zubarah explores how our perception of the world informs our relationship with reality. See pXXX.

Urban Intervals by Maryam Al Homaid

A carpet depicting some of Doha’s overlooked architectural landmarks from the 1980s and 1990s; it hangs in the lobby of The Ned. See pXXX.

that would finally send man soaring through the skies. Located at either end of the arrivals hall.

Ahmed Al Bahrani (b.1967; Iraq)

A Message of Peace to the World (2018)

Bahrani is one of the most famous Iraqi artists, although he now lives between Qatar and Sweden. This bronze sculpture takes the form of a cube with its surfaces decorated with elements that honor the work of Qatar-based non-profit organization Reach out to Asia. Located in the passenger train’s south node station.

Maurizio Cattelan (b.1960; Italy)

Turisti

Forty taxidermied doves sit on top of the flight information boards. The work is a reiteration of an installation of the same title, featuring pigeons, at the Venice Biennale in 1997 that appeared to mock the relentless tourist flow through the city.

Tom Claassen (b.1964; Netherlands)

8 Oryxes (2013)

The Dutch artist and sculptor Tom Claassen is well known for his depictions of wildlife. This is a group of life-size, cutely abstracted, bronze representations of the national animal of Qatar. QM shops sell a limited collectors’ edition miniature replica of one of the oryxes, which makes a great gift for any art lover. Located in the arrivals hall, towards the taxi pavilion in the east

Tom Claassen (b.1964; Netherlands) Falcon (2021)

This is a gigantic, abstract representation of Qatar’s national bird. Taking inspiration from the falcon’s soft feathers, the sculpture’s curves echo flight paths from Qatar to the rest of the world,

while also referencing the folds in the fabric of traditional Qatari attire. The falcon sits on a ledge facing the airport’s departures hall.

Urs Fischer (b.1973; Switzerland)

Untitled (Lamp/Bear) (2005–06)

It is probably the most photographed object at the airport—a social media post with Urs Fischer’s Lamp/Bear is the surest way to let everybody know you’ve either just arrived in Qatar, or you are off on your travels. Despite its looks, the giant teddy bear is not made of fur and foam but of cast bronze. This is the largest of three editions (two yellow, one blue), at seven meters tall. Located in the departures hall.

Ali Hassan (b.1956; Qatar)

Desert Horse (2016)

The artwork is an interpretation of the iconic desert horse composed of different forms of the Arabic letter N. It embodies the beauty of Arabic calligraphy as well as capturing the spirit of the animal and the feeling of movement. Located outside the arrivals hall, gate number 3.

KAWS (b.1974; USA)

SMALL LIE (2018)

This is one of American artist KAWS’s signature, slumped, doll-like figurines, blown up to giant size (9.75m). Executed in afrormosia wood, the inspiration for the piece comes, according to the artist, from the wooden toys he had as a child. It is the first time one of his works has been installed in an airport. Located at the north node, near concourse C.

Jean-Michel Othoniel (b.1964; France)

Cosmos (2018)

Othoniel often uses giant glass beads in his work: in 2000 he designed a new entrance for the Palais Royal-Musée du Louvre station of the Paris Métro using large metal balls and colored glass globes; in 2006 he hung necklaces of large beads made by master glass-blowers in Murano on the building housing the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice. Cosmos is made up of strings of golden beads that form a globe, while suggesting endless intercultural communication and collaboration. Located at the north node, near concourses D and E.

Tom Otterness (b.1952; USA) Other Worlds (2014)

Otterness is known for cartoonish statuettes in bronze. His characters populate New York’s 14th Street/ Eighth Avenue subway station. For QM, he created eight, loosely figurative bronze sculptures, grouped across three sites, with slides and seats for limbs and playpen-like chambers for torsos. These large-scale figures invite visitors to engage with the works. Located in concourse C, near gates C2, C3, and C8.

Marc Quinn (b.1964; UK)

Arctic Nurseries of El Dorado (2011)

Although this large sculpture, depicting a hybrid flower/plant, is cast in heavy bronze, it is coated with a white pigment that makes it look like porcelain. The piece represents globalization and the potential to fly flowers in from all over the world in a day. Located in the departures hall.

Anselm Reyle (b.1970; Germany) Philosophy (2009)

Reyle is known for his found-object sculptures, typically made with fluorescent colors, discarded objects, and shiny materials such as

foil, glitter, and mirrors. This particular piece uses chrome-like modules that interlock in complex patterns to form a shiny, rippling wall. Located in the Mourjan lounge.

Rudolf Stingel (b.1956; Italy)

Untitled (2016)

Casting and plating graffiti-covered insulation panels has become one of Stingel’s trademark styles. His untitled installation at the airport celebrates and honors all the workers who helped to build the airport. The signatures and initials of the workers are engraved in the body of the artwork. Located in the arrivals hall, towards the bus terminal in the west.

Xavier Veilhan (b.1963; France)

Portrait of Jean Nouvel (2009)

Veilhan is an artist who has represented France at the Venice Biennale in 2017. This is one of a series of architects originally sculpted for a solo exhibition at the Château de Versailles, near Paris. Nouvel, of course, is the architect of the National Museum of Qatar and Doha Tower.

Bill Viola (b.1951; USA)

Crossroads (2014)

Viola is a video artist who works primarily with image technology in new media. His works focus on the ideas behind fundamental human experiences. Displayed on a large, panoramic screen, Crossroads has a series of figures pulsating in the heat of the desert, emerging from mirages and advancing toward viewers. As they approach, each person crosses a threshold from mirage to clarity, making visible their humanity and individuality. Located in the transit lounge.

Downtown

Shua’a Ali (b.1974; Qatar)

Milestones (2022)

This is a conceptual representation of an important period in the economic history of Qatar. The three elements of the piece symbolize the financial system, which has evolved from being defined by the hand-to-mouth existence of pearl diving to wealth and prosperity, represented here by a gold stone. Located at the Grand Hamad Plaza.

Salman Al Malek (b.1958; Qatar)

Al Jassasiya (2022)

The installation takes its name from the Al Jassasiya rock art site, on the northeast coast of Qatar, where hundreds of petroglyphs have been found. Malek’s playful tubular shapes reference some of these glyphs. Located on Ali Bin Amur Al Attiya Street, a block south of Museum Street, midway between the National Museum of Qatar and Souq Waqif.

At the stadiums

Faraj Daham (b.1956; Qatar)

The Ship (2022)

Daham’s work is also inspired by the rock carvings at Al Jassasiya. Their clear references to seafaring and trade have been carved into the artwork by Daham himself. They underscore the prominence of the Arabian Gulf in terms of trade, transport, fishing, and pearl harvesting, as well as their connection to the past. Located at Al Janoub Stadium, Al Wakrah.

Shilpa Gupta (b.1976; India)

I Live Under Your Sky Too (2022)

Gupta presents a light installation in the form of an animated sentence in which her handwriting rises and shines from lines of a ruled book to read, “I Live Under Your Sky Too” in three interwoven languages: English, Arabic, and Malayalam. Using national and migrant languages, the work emphasizes the message that there is a space for us all. Located at Stadium 974, Ras Abu Aboud.

Ugo Rondinone (b.1964; Switzerland)

Doha Mountains (2022)

Inspired by naturally occurring hoodoos (spires or pyramids of rock) and the art of meditative rock balancing, Rondinone’s Mountain sculptures (2015–ongoing) mediate

between geological formations and abstract compositions, consisting of vertically stacked rocks painted in varying colors. Located at Ras Abu Aboud beachfront.

Qatar University

Etel Adnan (1925–2021; Lebanon)

Untitled I and II

The work of Lebanese artist Etel Adnan adorns an outdoor space on the Qatar University campus and takes the form of two, large-scale, colorful ceramic murals.

Eduardo Chillida (1924–2002; Spain)

Buscando La Luz (Searching for Light) IV (2014)

The monolithic iron sculpture rising eight meters from the ground is large enough for an individual to stand inside. Open on one side and at its top, the totem-like column is directed towards the sky and life-giving sunlight.

MIA Park

Works by Dia Azzawi, Saloua Raouda Choucair, Liam Gillick, Richard Serra, and Najla El Zein. See pXXX.

National Museum of Qatar

Works by Ahmed Al Bahrani, Simone Fattal, Ali Hassan, Bouthayna Al Muftah, Jean-Michel Othoniel, Aisha Al Sowaidi, Hassan bin Mohammed Al Thani, and Roch Vandromme. See pXXX.

Souq Waqif

Work by César Baldaccini. See pXXX.

Msheireb

Works by Shua’a Ali, Isa Genzken, Subodh Gupta, Mark Handforth, Guillaume Rouseré, and Abdulaziz Yousef (aka TEMSA7). See pXXX.

Al Bidda Park

Works by Mohammed Al Ateeq, Shezad Dawood, Fischli & Weiss, Isa Genzken, Ghada Al Khater, Jeff Koons, Salman Al Malek, Faye Toogood, and Franz West. See pXXX.

West Bay

Works by Saloua Raouda Choucair, Martin Creed, Katharina Fritsch, Faisal Al Hajri, Monira Al Qadiri,

Suki Seokyeong, and Tony Smith. See pXXX.

Katara

Works by Subodh Gupta and Lorenzo Quinn. See pXX

Lusail

Works by Ahmed Al Bahrani, Marco Bruno and Michael Perrone, Saloua Raouda Choucair, and Shouq Al Mana. See pXXX.

Education City

Works by Louise Bourgeois, Damien Hirst, M.F. Husain, and Choi Jeong

Hwa. See pXXX.

Aspire Zone

Works by Daniel Arsham (inside the Olympic and Sports Museum) and Sarah Lucas. See pXXX and pXXX

Al Zubarah

Works by Simone Fattal, Ernesto Neto, and Olafur Eliasson. See pXXX

Zekreet

Work by Richard Serra. See pXXX

ARCHITECTURE

Qatar’s looks to its architectural heritage to provide a blueprint for a sustainable future

Traditionally, Qatar’s architecture has been shaped by two important factors: the climate and the paucity of building materials. The principal purpose of local architecture was to

protect its inhabitants from the heat of the sun. Walls were built thick to keep the heat out, with small windows and devices to take advantage of any cooling breezes,

10 LANDMARK QATAR BUILDINGS

Palace of Sheikh Abdullah

bin Jassim Al Thani (c.1880)

A palace complex that is one of the best surviving examples of traditional Qatari architecture. See pXXX.

Sheraton Grand Doha (1982)

The first building constructed in West Bay looks like something out of Star Wars. It’s a striking example of Gulf brutalism. See pXXX.

General Post Office (1982)

Another landmark early building, also designed in a brutalist style—it wouldn’t have looked out of place in East Germany. See pXXX.

Museum of Islamic Art (2008)

It contains one of the world’s finest collection of Islamic art, but I.M. Pei’s spectacular building is a must-see in its own right. See pXXX.

Doha Tower (2012)

Jean Nouvel’s tower is similar to his earlier Torre Agbar in Barcelona and is also one of the most beautiful tall buildings in the Middle East. See pXXX.

Qatar National Library (2017)

This OMA design is a light-filled structure that embraces the pursuit of knowledge. See pXXX.

Msheireb metro station (2019)

Doha’s metro system has glorious vaulted internal spaces and instantly recognizable above-ground stations; Msheireb is the grandest of all. See pXXX.

Barahat Msheireb (2019)

The architecture of Msheireb is uniformly excellent and seen at its pedestrian-friendly best in this plaza. See pXXX.

National Museum of Qatar (2019)

In a country of remarkable buildings, Jean Nouvel’s audacious National Museum stands out. See pXXX

Lusail Stadium (2022)

All the stadiums used for the FIFA World Cup are stunning, but the golden bowl that hosted the final, with a design inspired by the fanar lantern, is radiant. See pXXX.

such as malqaf, or wind-catchers. Internal courtyards allowed for outdoor activities with protection from the sun and wind, and at night they served as air-wells, into which the cooler night air could sink. This introverted arrangement also suited the Islamic way of life, in which privacy and the shielding of women was paramount. With the focus of life turned inward, buildings showed a blank face to the outside. Any decoration was confined to the roofline. Buildings tended to be closely clustered to create shady alleys. With the scant availability of stone and wood, most were constructed of hasa (rubble) fixed with juss, a white powder used as a mortar and paint after mixing with water. Roofs were made of jareed, a ribbing made with palm branches.

1970s Modernism

The declaration of the independence of the State of Qatar in 1971 inspired a spirited new architecture. Around this time, the northern part of Doha Bay was dredged to create what was then called the New District of Doha (NDOD), and plans for here included Qatar University, diplomatic areas, and a 500-bed hotel and conference center. Qatar appointed the American architectural practice founded by William Pereira (1909–85), best known for its iconic Transamerica Pyramid (1972) in San Francisco, to design the hotel, which takes the form of a truncated pyramid topped by an additional platform level angled out from the rest of the building. Inside, it has a 13-story atrium banded by internal balconies. Inaugurated in 1982 as the Sheraton Grand Doha, it was the first building to be constructed in what is now West Bay. It gave a forward-looking image to Doha as the city began a period of rapid expansion.

A similar esthetic informed other buildings constructed in Doha around this time, notably the Ministry of Finance (1984), by Japanese architect Kenzo Tange, a concrete-framed, granite-clad modernist structure on the Corniche (opposite the Museum of Islamic Art), the General Post Office, and the National Theater. The General Post Office was designed in the late 1970s by the British firm Twist + Whitley Architects. It recalls the brutalist concrete architecture then common in Europe, but it has its own unique character shaped by the clustered semi-circular apertures that cover the roof and make the building look like a pigeon loft (a reference to old-school methods of sending messages). The apertures allow light into the great hall below, which contains more than 25,000 electronically operated post-office boxes, necessary because most homes in Doha lack specific street addresses or post boxes, and there are no regular delivery services to residents.

Iraqi-born Egyptian architect Kamal El Kafrawi (1931–93) broke new ground by fusing concrete modernism with Qatar’s own architectural heritage in his 1970s design for Qatar University Kafrawi’s design uses a grid of modular octagonal units made of white precast concrete, each topped with a traditional Arab wind tower to allow indirect natural light and cooling ventilation through openable windows within the roof structure. The university was inaugurated in 1985 and represents a fascinating expression of a modern Qatari architecture and an affirmation of the interest of the State of Qatar in modern design.

A 21st-century Qatari style

During the construction boom that began in the new millennium, the government did something interesting. Until now, the great statement buildings of Qatar were primarily creations of the state. Now, the state said it wasn’t going to build more government buildings, instead it would let private developers take the reins and the

government would lease property. Keen to avoid the sprawl of generic glass towers that anonymizes so many world cities, Qatar promoted the use of an architecture inspired by the local vernacular. This has given rise to a preference for developments with minimalist design of plain surfaces that play on light and shadow, recesses and apertures, and subtle patterning. This is seen to best effect in the Katara Cultural Village and the Msheireb neighborhood.

While Doha does have its share of skyscrapers, they are zoned. The quality of the developments is also bolstered by the integration of projects headed by a panoply of award-winning international architects. So the star of the West Bay skyline is the Doha Tower by French architect Jean Nouvel, and the new Lusail Boulevard is anchored at one end by the majestic quartet of British architect Norman Foster’s Lusail Towers. Architects of global stature have also been heavily involved in shaping entire new districts. Education City, for example, was masterplanned by influential Japanese architect Arata Isozaki, and has since evolved with contributions from Rem Koolhaas and OMA, Legorreta + Legorreta, and César Pelli. Meanwhile, Qatar Museums is embarked upon an ongoing ambitious program to create a succession of landmark cultural institutions, achieved with the help of a starry array of architects including Alejandro Aravena, Ben van Berkel, Herzog & de Meuron, Rem Koolhaas and OMA, I.M. Pei, and Jean Nouvel. In most cases, these architects have engaged with Qatar’s own built heritage, and its unique topographical and climatic conditions, to create an architecture that is unique to the nation.

HISTORY

As a modern nation, Qatar is young but this peninsula of land has a human history that dates back thousands of years

The early inhabitants of what today is Qatar were desert-dwelling Bedouin hunter-gathers. Early each summer they moved to the coast for the start of the pearl-diving season. Pearls found in the rich beds off the coast of Qatar were renowned for their beauty and have been prized and traded since. As well as being a rich source of food and natural resources, it was via the sea that Qatari traders connected with networks that stretched as far as China. These relationships brought diverse cultural influences.

New cultures also traveled overland, as when in the first half of the 7th century, Islam spread throughout the Arabia. The shared new religion helped erase old tribal rivalries, replacing them with a new-found Muslim kinship that inspired a golden age of trade.

Foreign powers in the Gulf

In the early 1500s, following their discovery of a sea route around Africa, the Portuguese began to exert control over maritime trade in the Red Sea and Arabian Gulf. They

captured commercial centers and imposed heavy taxes on the pearl trade. Meanwhile, from their capital of Istanbul the Ottomans exerted their influence throughout the Middle East and into the Gulf. The imperial powers skirmished for control. In the early 1600s the rivals found it expedient to form an alliance against the rising threat of British expansion, represented by the British East India Company. The British allied themselves with the Safavid Empire of Iran and together they ousted the Portuguese and Ottomans from the Gulf.

In Qatar at this time, the main settlements were Al Zubarah and Al Huwailah, both on the north coast, Al Ghuwairiyah, also in the north but inland, Al Wakrah and Al Bidda. Al Zubarah was one of the most important and prosperous cities thanks to the trade in pearls. Its wealth made it a target for attacks by neighbors Bahrain and Saudi Arabia.

In 1820, the British, concerned that turbulence in the region might disrupt their own trade with India, brokered a treaty among Arab leaders. The following year, the British deemed that Qatar had breached the treaty and bombarded Al Bidda. British naval officers completed the first survey of Qatar’s coast in 1823, providing detailed information about Qatari coastal towns, features, and water depths to aid navigation. It’s around this time that Doha is founded as an offshoot of Al Bidda.

Tensions between Qatar and Bahrain continued. In 1867, Bahrain, supported by the ruler of Abu Dhabi, destroyed both Al Wakrah and Al Bidda. The following year, the British took punitive measures against Bahrain and recognized the

authority of tribal leader Sheikh Mohammed bin Thani as the most prominent leader of Qatar, leading to the emergence of the Thani family and the beginnings of modern Qatar.

The birth of modern Qatar

Following the 1868 agreement, competition escalated between Britain and the Ottoman Empire over Qatar. The Turks sent troops to occupy a fort in Doha. It fell to Sheikh Jassim bin Mohammed bin Thani (r.1878–1913), son of the aging Sheikh Mohammed, to navigate a path between the two powers and retain Qatar’s independence. In 1893, matters came to a head when the Ottoman governor of Basra arrived in Al Bidda with his forces and carried out a surprise attack on Sheikh Jassim’s headquarters at Al Wajbah, 10 miles west of Al Bidda. Sheikh Jassim prevailed, scoring a landmark victory.

Ottoman forces withdrew and, in 1916, the Anglo-Qatari Treaty guaranteed British protection of Qatar. Even so, the early decades of the 1900s were one of the darkest periods in the nation’s history. The country was struck by a series of epidemics and famines, and lost trade caused bythe First World War. Worse was to come. In 1929, share prices on the New York Stock Exchange crashed, triggering a worldwide economic depression. Demand for pearls dropped drastically. Around the same time, the Japanese began producing cultured pearls in large quantities and at low cost. The Gulf pearl trade collapsed.

Oil and independence

At this low point in the nation’s fortunes, a new hope appeared. Following years of exploration and testing, oil was struck at Dukhan, in

western Qatar, in 1939. Drilling operations were suspended for the duration of the Second World War, but resumed in 1946, and the industry grew rapidly. The next couple of decades marked the beginning of a new oil-fueled era in Qatar’s history, with the foundation of state institutions such as a police force, fire service, national bank and a first post office. Following the termination of the 1916 Protectorate Treaty with Britain, Qatar declared its independence on September 3, 1971. The ruler at the time, Sheikh Ahmad bin Ali Al Thani (r.1960–72), became the first amir.

The year after independence, Sheikh Khalifa bin Hamad Al Thani (r.1972–95) became amir. He reformed the government and strengthened relationships abroad, establishing the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, appointing ambassadors and leading Qatar into the United Nations. His reign saw the opening of Qatar University, the first Qatar National Museum, and Al Khalifa Stadium, as well as the founding of Qatar Airways. Sheikh Khalifa also oversaw the urban development of Qatar, commissioning several planning schemes, most notably the

1977 Doha Masterplan, which would decisively shape the future growth of the capital.

Qatar today

The accession of Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani in 1995 marked a new phase in Qatar’s history, with a focus on education, health, sports, culture, infrastructure, and media. The news station Al Jazeera was established in 1996 and a first permanent constitution was enshrined in 2004. Sheikh Hamad’s reign was also defined by the country’s increasing presence on the global stage, hosting major sporting and cultural events, such as wining the bid for the 2022 FIFA World Cup. In 2008, Qatar defined its future goals through the Qatar National Vision 2030.

In 2013, Sheikh Hamad abdicated in favor of his son Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani. Since then, the nation has maintained a trajectory of development, prosperity and global influence. His Highness Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani continues the pioneering work of his father to diversify the national economy and invest in Qatar’s younger generation.

HA

ORIENTATION

Doha is the capital of Qatar. It sits on the Arabian Gulf, midway along the east coast of the Qatar Peninsula. With a population of 1.2 million, it is home to about 75 per cent of the nation, many of whom have arrived in the past 20 years, during which time the city has undergone rapid expansion. Its geography, however, remains relatively compact, and it is quick and easy to get around. No place is too far from any other.

The old heart of the city is Souq Waqif and the recently redeveloped Msheireb district. Immediately east of these, straddling the seafront Corniche, is the museum triangle with the landmark National Museum of Qatar and Museum of Islamic Arts, and the site

GETTING AROUND DOHA

that will eventually become the Art Mill Museum. Immediately north are the grassy expanses of Al Bidda Park, linking to the high-rises of West Bay, dense with five-star hotels. Beaches fringe the northern edge of West Bay, running all the way up to Katara, a cultural village with museums and entertainment, and a center for shopping and dining. Just beyond Katara, a causeway links to The Pearl, a cluster of largely residential islands, while the main expressway continues north, crossing a creek, to the new city of Lusail, with its attractive seafront promenade. Two other areas of interest to visitors, Education City and the Aspire Zone, are a few miles inland of the coast, reachable by car or metro.

Doha is quite spread out and some form of transport is needed to get between neighborhoods. Happily, the city has an excellent metro system that reaches most places a visitor might want to go.

TO/FROM THE AIRPORT

Taxi

Follow the signs to the taxi pavilion located off to the left as you enter the arrivals hall from baggage reclaim. Choose between sedans or special taxis for larger families or passengers traveling with a lot of baggage. Doha’s Karwa taxis are bright blue and operated by the state-owned Mowasalat transportation company; they can be booked in advance from the call center (+974 800 8294) or via the Karwa app. Drive time from the airport to central Doha obviously depends on traffic, but on average it is between 15 and 30 minutes.

Bus

Buses run by Mowasalat connect the airport with various destinations across the city. All

depart from the bus pavilion, which is off to the right as you enter the arrivals hall from baggage reclaim.

Metro

There is a metro station at the airport offering fast and frequent connections to central Doha; from the airport to Msheireb at the heart of Downtown is just five stops and takes 17 minutes. See below for operating hours.

METRO

The metro is a new (launched in 2020), state-of-the art transport network running mostly underground across Doha. It’s fast, it’s clean, rarely crowded, and it will get visitors most places they want to go. Trains have three classes of travel: standard, which is for everybody; family, which is for women and children, and men

only if accompanied by a female; and gold, which has larger and more comfortable seats than the other two classes and is only for travelers with Goldclub cards.

At present there are three lines (Red, Gold, and Green) and 37 stations. Many stations link up with bus and minibus routes for onward travel. Future phases involve the introduction of an additional line and the expansion of the existing ones. The design of the stations, with their vaulted spaces, is inspired by traditional Bedouin tents. The largest is Msheireb, where the Red, Green, and Gold lines all meet. A single journey costs QAR2 and a day pass is QAR6. Travel cards that are topped up with credit cost an initial QAR10. Travel cards and day passes can be purchased at self-service machines at all metro

stations. Trains run from approximately 5.30am to midnight Sunday to Wednesday, 5.30am to 1am Thursday, 2pm to 1am Friday and 6am to midnight Saturday.

TRAM

There are several tram services around Doha. The most extensive network is the Lusail Tram, which at the moment is a single line that runs underground and is almost indistinguishable from the metro, which it connects with at Legtaifiya station. However, the service is in the process of being extended and it will eventually cover 14 miles with four lines and 25 stations (15 above ground and 10 underground). Metro travel cards work on this system. The tram’s hours are the same as the metro.

There are also self-contained tram networks in Msheireb and Education City; these are free of charge to ride.

BUS

Mowasalat buses run across the city between eight stations. For more information download the Karwa Journey Planner app. In addition to the general network, a number of Metro Link bus services shuttle passengers to and from metro stations; these operate at DECC (around West Bay), Legtaifiya (connecting with The Pearl), and Al Waqra, shuttling between the station and the souq, among other places.

MATHAF BUS

The Mathaf bus is a free-to-ride service that runs between Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, the National Museum of Qatar, the Museum of Islamic Art, and Fire Station. The bus runs every hour

9am–7pm Saturday to Thursday and 1:30–7pm Friday.

TAXIS/UBER

All taxis are operated by the state-owned Mowasalat Co., operating as Karwa Taxi. You can find them at prominent locations, such as hotels and malls, or you can book them through the Karwa app or call +974 4458 8888. The meter starts at QAR7 (the minimum fare), which covers the first 1.8km, then QAR1.6 per km after that. It goes up to QAR1.9 per km at night. Taxis accept card payments.

Uber operates in Qatar using the same app as in other countries.

WALKING

Certain neighborhoods, including Education City, Katara, Lusail, Msheireb, and Souq Waqif, are suitable for exploring on foot, heat permitting. But, otherwise, the distances between districts mean that visitors should expect to make frequent use of taxis, Uber, or the metro.

SIGHTSEEING TOURS

Doha Bus is a hop on/hop off day and night sightseeing service. It takes in such sights as the National Museum, Museum of Islamic Art, Katara Cultural Village, and The Pearl. It operates 10am–6pm daily, with a night tour departing from the Souq Waqif bus stop at 7pm. Tickets cost QAR180 and are valid for 24 hours. See dohabus.com for further details and booking.

DHOW CRUISES

Traditional dhows are docked all around the harbor off the Corniche, by the Pearl Monument. They offer all manner of cruise packages, day and night, with or without a meal. The best time to be out is sunset. Rates start anywhere from QAR20 to QAR25 per person; you get better deals if you go as a group. Cruises can also be organized by many of the local tour agencies.

MUSEUM TRIANGLE

You won’t find anything called the Museum Triangle on a map of Doha—not at present, anyway—but that is what some people have taken to calling the area on the south side of Doha Bay that encompasses the Museum of Islamic Art (MIA), the National Museum of Qatar (NMoQ), and the industrial flour mill that is soon to become the Art Mill Museum of modern and contemporary art. This area is fast becoming one of the major cultural hubs of the city, including, as it does, Al Riwaq exhibition center and MIA Park, which is the setting for a wide variety of cultural elements and happenings, from pieces of public art to open-air cinema screenings.

It is the first bit of the city seen by visitors arriving by sea, as the route from the new cruise terminal runs beside MIA Park. It is also only a short walk from the popular downtown neighborhoods of Souk Waqif

and Msheireb. The museums straddle the Corniche, the waterfront highway and pedestrian promenade that is one of the glories of Doha for the magnificent and ever-shifting views it offers of the city skyline seen across the water.

In the near future, the three major museums and the park will all be connected by a new Cultural District promenade, conceived by the award-winning English urban-landscape designer James Corner, whose Field Operations practice led the design and construction of the acclaimed High Line in New York.

MIA PARK

At the heart of the triangle is this beautiful and extensive landscaped green swathe beside Doha Bay, with terrific views across to West Bay. In addition to family-friendly lawns and looping walks shaded by palms, the park provides access to the magnificent Museum of Islamic Art (see pXXX) and has a major exhibition venue in the form of Al Riwaq (see pXXX).

At the tip of the park is 7 (2011), a 24-meter-high steel artwork by American sculptor Richard Serra (b.1938). Constructed from seven steel plates arranged in a heptagonal shape, this elegant piece of public art celebrates the scientific and spiritual significance of the number seven in Islamic culture. Other pieces of art in the park include Folded Extracted Personified (2018) by Liam Gillick (b.1964, UK), a series of panels, each of which features a figurative work from the MIA collections with a circular hole where the figure’s head would be, encouraging visitors to stick their own head in it for a selfie. There is also Enchanted East (2016) by Dia Azzawi (b.1939, Baghdad), which is a carousel with 40 animal “seats” inspired by the MIA collections, and Bench (1969–71) by Lebanese artist Saloua Raouda Choucair (1916–2017), a sculpture comprising 17 interlocking limestone pieces that form a semicircular seat.

Further reasons to visit include children’s playgrounds, seasonal open-air film screenings, regular sports events, art workshops, a market, bungee trampolines, bicycle rentals, kayak tours, and stand-up paddle-board training. There are several

food vans along the waterfront, and close by the Richard Serra sculpture is the MIA Park Coffee Shop, with a waterfront terrace and lounge chairs offering one of the finest views in Doha. Free golf-cart shuttles are on-hand to ferry visitors around the park.

FLAG PLAZA

This new public plaza at the edge of MIA Park was opened just in time for the FIFA World Cup 2022™. It flies 119 flags representing nations with diplomatic missions in Qatar, as well as the European Union, United Nations and Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). The plaza plays host to festivals and other community events. It is also home to a large-scale piece of public art, Us, Her, Him (2022), by French-Lebanese artist Najla El Zein (b.1983, Beirut), whose works explore the relationship between form,