words

things

words & things

f o u r n o catalogue deancooke rare books ltd

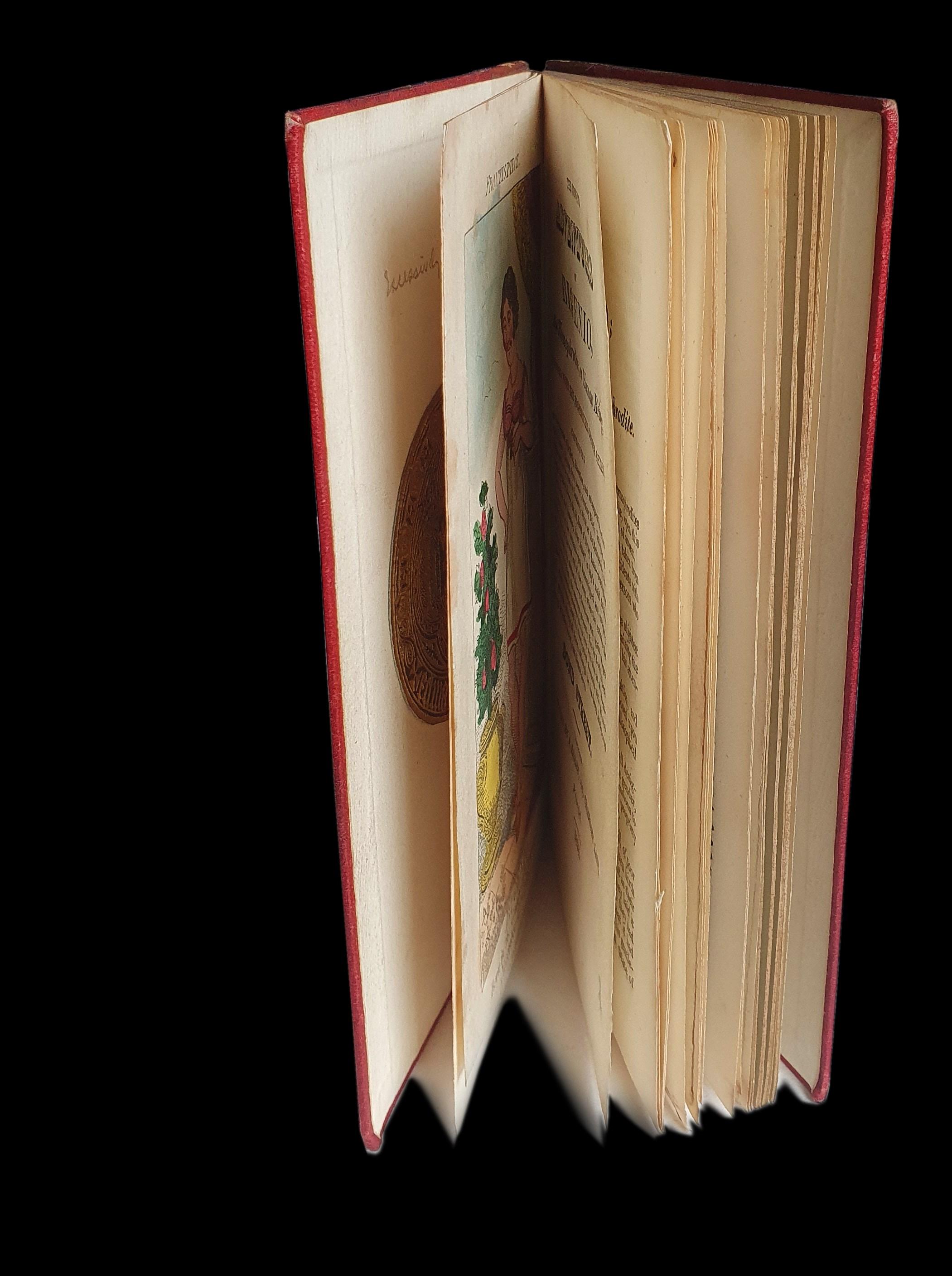

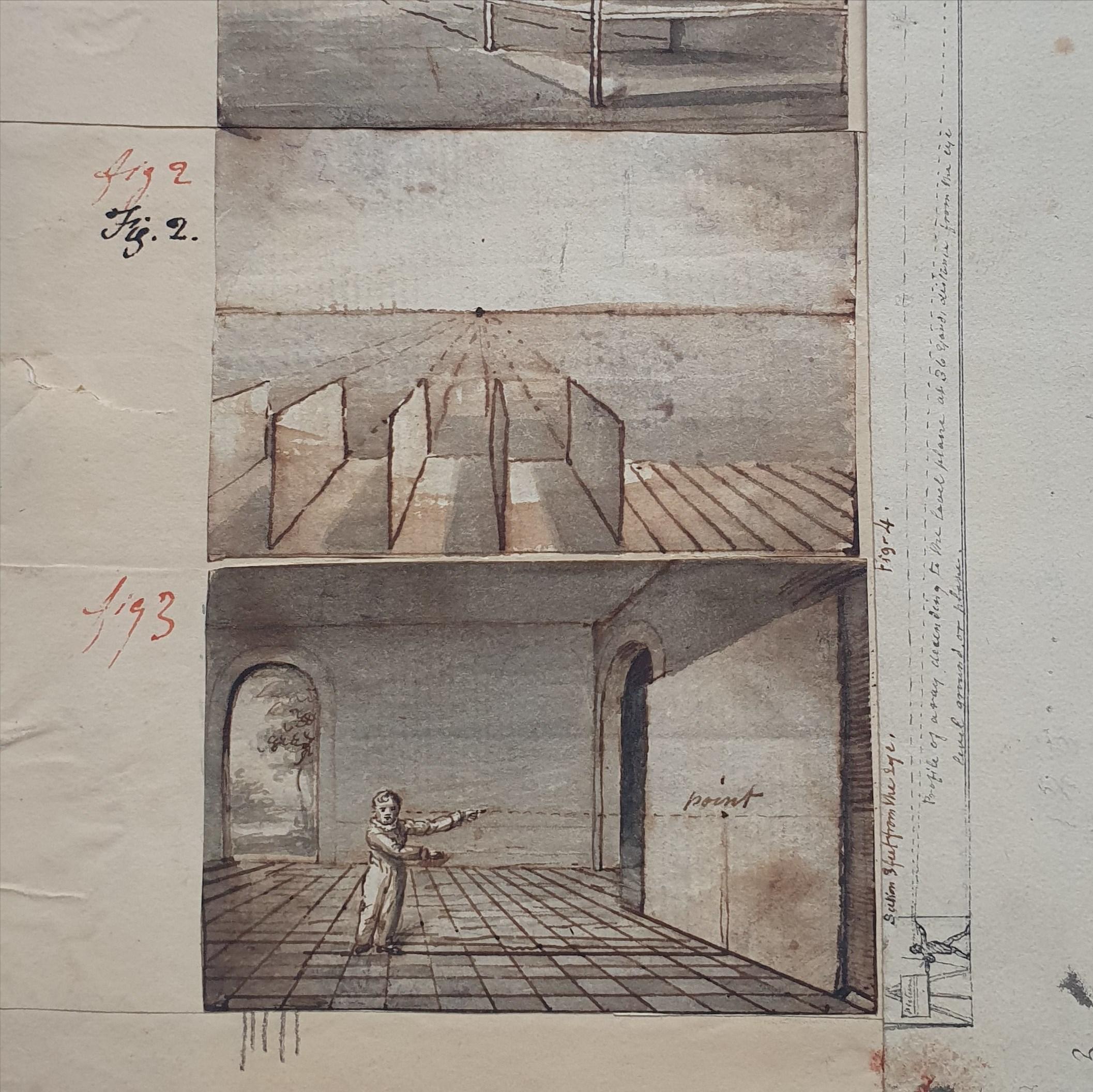

[BIGENIO] The Surprising Adventures of Bigenio, An Hermaphrodite, or Human Being, endowed with the propensities of both sexes; containing a true account of its Birth, Education and subsequent Seduction by its Tutor; Eloping from home; turning Thief; Intrigues in Bath and on the road to London; arrival at the Metropolis; entrapped by M S , the old Bawd of Drury Lane description of her house and inmates; hires himself as lady’s maid to Mrs. D.; found out by husband gets horsewhipped and escapes; takes lodgings at the west end of the town, where he entraps the son of a Banker, who marries him is found out and again escapes with upwards of £500, the marriage present; flies to York, where the rich old mai Miss Dornton falls in love with him at an assembly, whom he marries, and in a short period absconds with £2,000 and upwards, eluding all trace, although he has been lately seen passing in Oxford Street, and thence sown BOND STREET.

London: Printed by J. Bailey, 116, Chancery Lane. Price 6d. 1824.

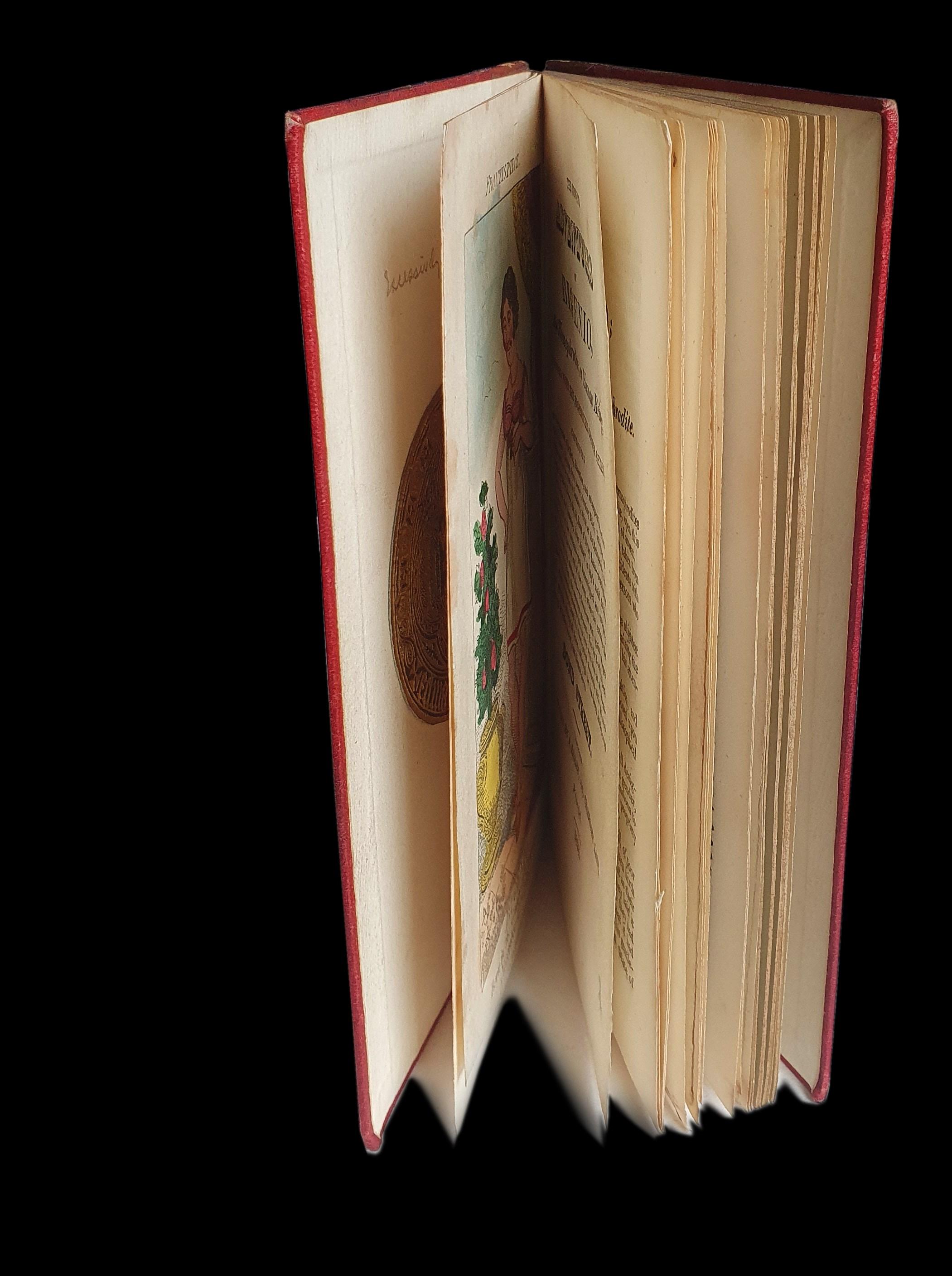

Duodecimo. Signatures: A-B6, C2. Pagination 28 p., hand-coloured frontispiece (lower left margin of frontispiece torn with loss to several letters of the publisher’s details).

Red morocco backed boards, circular armorial gilt book label of Edward Hailstone (1818-1890), British book collector and antiquary, fifth son of the botanist Samuel Hailstone (1767-1851).

¶ The intersex protagonist of this tale is depicted as both monster and beguiling object of desire. The first thing the reader –or, perhaps more importantly for the chapman hawking it, the buyer – sees on opening the book is an image of a handsome, moustachioed individual whose skimpy dress reveals enough to convey a sexually indeterminate, but also alluring persona.

According to Greek mythology, Hermaphroditus, the beautiful child of Hermes and Aphrodite, merged the male and female sexes into one. Hermaphrodites have long been recognised by the medical profession, but attitudes have ranged from serious scientific investigation to outright denial of their existence. For example, James Parsons, writing in the 18th century, was sceptical of the classification, preferring instead to reduce all possible cases of intersex people to women with genital deformations 1 .

More widely, interest in liminal characters appealed as much to those who wished to explore the transgressive side of the human psyche as to those who feared it and preferred to banish them to the margins of society or the safety of cheap literature.

THE PRINTER

The book was printed by John Bailey, son of Susan and William Bailey, both of whom were publishers and printers. William died in 1794, and Susan ran the company under her own imprint. In her will she left the business solely to her two daughters. Of her two sons, John established himself as a printer at several London locations over the next two decades before settling at 116 Chancery Lane, where this book was printed in 1824.

1. SUBJECT AND OBJECT

PRECEDENCE

John Bailey was a prolific publisher of books but specialised in neatly packaged stories in 24 or 28 pages sold as chapbooks. Among his publications is a reprinting of Henry Fielding’s The Female Husband 1746. Bailey produced it as a chapbook in 1813, complete with a hand-coloured frontispiece showing its bare breasted heroine being publicly flogged. The story was based on the life of Mary Hamilton who took the identity of a man, assumed the name Charles, and married several unsuspecting women. Perhaps success with this publication served as a spur to publish another story with a liminal protagonist and a titillating frontispiece. Although we can find no trace of an individual whose story follows the trajectory of ‘Bigenio’, Bailey suggests that we “need look no farther than into the Philosophical Transactions” (p.3) of the Royal Society for evidence of their existence. It is true that a search of articles in the Philosophical Transactions published before the book’s 1824 printing yields 41 concerning hermaphrodism. However, only about half a dozen are solely concerned with the subject of intersex humans, and none seem to match Bigenio’s adventures, so it seems his claim is a general appeal to scientific authority rather than a retelling of a documented life

ONE OR TWO BIGENIOS?

This is an unrecorded edition, having likely fallen victim to a kind of inverse law of publication in which the greater the circulation at the time of production, the scarcer it is now. There is only one other known copy of a title resembling this one, located at the Bodleian Library, Oxford (Douce FF 73 (8)). It too was printed by John Bailey, but the signatures and typesetting are different. The Bodleian copy collates A2, B12, and does not have a frontispiece, whereas ours is A-B6, C2, with a hand-coloured frontispiece.

Comparison of the two texts raises interesting questions, especially in the different uses of pronouns. The title page of the Bodleian copy begins The life and adventures of Bigenio, an hermaphrodite and goes on to promise descriptions of “nightly scenes” and the “nuptial night!”, which are not in the title page of ours, but these promises are unfulfilled: both texts opt for the coy narrative that “What happened that night decency forbids me to declare” (p.21 in our copy, but p.22 in the Bodleian copy). In our copy, the narrative is supposedly “taken from a well authenticated fact” which was reported by “persons who were acquainted with the monster” (p.3), but this justification does not occur in the Bodleian copy.

The two publications diverge in their uses of pronouns. The Bodleian copy uses “he” consistently in their title page, which reads:

The life and adventures of Bigenio, an hermaphrodite : containing an account of his seduction by his tutor, for which he absc protector's house, and his singular adventures in London and Bath: he is induced to enter into a brothel by the noted Mother description of its nightly scenes! He enters into the service of a certain Lady, as her maid, from which an unlucky discovery abscond. He dances a new hornpipe to a new tune; attended with unpleasant accompaniments. Commences business on his own accou Captivates a young Gentleman, who marries him. Description of the nuptial night! More unpleasant discoveries. Is obliged to l and arrives at York, where he marries a Lady with £2000 a year; and again absconds. The whole interspersed with many amusing

whereas our title page (see above) begins by using “its” (e.g. “containing a true account of its Birth, Education and subsequent Seduction by its Tutor”) before switching to “he/his/himself” (“hires himself as lady’s maid to Mrs. […] he has been lately seen passing in Oxford Street”). On the first page of the text in both versions, the matter of pronouns is supposedly settled: “In order to avoid a want of perspicuity, I shall designate the subject of this History by the masculine gender, and call it he, although it had equally pretensions to the feminine gender, and might with as much propriety have been designated by the monosyllable she.” Nonetheless, only a few pages later they drop the convention in a sentence where the character “Young Fallow” places “her” (i.e. Bigenio) “behind him on horseback”.

The Bodleian copy is undated, so we are unable to ascertain whether the pronouns and enticements of bedroom scenes to the title page were added in the earlier or later edition. But a more in-depth comparison of both texts may uncover further variances and yield answers to these and other questions.

REPULSION AND ATTRACTION

Bigenio is frequently referred to as a monster (“so great a monstrosity” p.17), or repellent (“what was the astonishment, horror, and confusion of the young ‘squire when he found he had to deal with an Hermaphrodite!” p.11). But they are more usually depicted as beautiful (“Bigenio had just turned his sixteenth year, was remarkably beautiful in the face [...] his elegance of shape and carriage” p.4) and sexually attractive (“Perhaps it may be thought he found nothing very luscious there, but Bigenio had two breasts that swelled out like blushing peaches, and were as soft as the finest down enclosed in a velvet case” p.6). Although many characters they encounter are repulsed when they discover that Bigenio is intersex, the book also explores what happens when prejudice meets reality and the latter triumphs: “a certain Lady of fortune” is repulsed by the very idea and “started back at the thoughts of an Hermaphrodite, and vowed she’d never have any commerce with it”, but is enamoured of the reality when she meets them “dressed in a most elegant attire”. We are told that “the lady [was], struck with his beauty and air, suffered her aversion to vanish and give place to lust” (p.21). But implicit in the story’s presentation – and its evident – is not so much the triumph of desire over disgust as their co-existence and interplay in people’s reactions to Bigenio’s dual nature.

Intersex people are seldom touched upon in literature, yet this book was clearly designed to appeal to a popular audience and appears to have sold well enough to warrant another, altered edition, creating an interesting conundrum over precedence. The volume offers a unique window onto a previous era’s attitudes to sex and gender – and the variations around the use of pronouns have an intriguingly modern resonance

SOLD Ref: 8104

James, A mechanical and critical enquiry into the nature of hermaphrodites. (1741).

2. <https://royalsocietypublishing.org/action/doSearch?

AllField=hermaphrodite&SeriesKey=rstl&AfterYear=1668&BeforeYear=1824&queryID=13/292241067>

2. SYNONYMOUS RELATIONSHIP

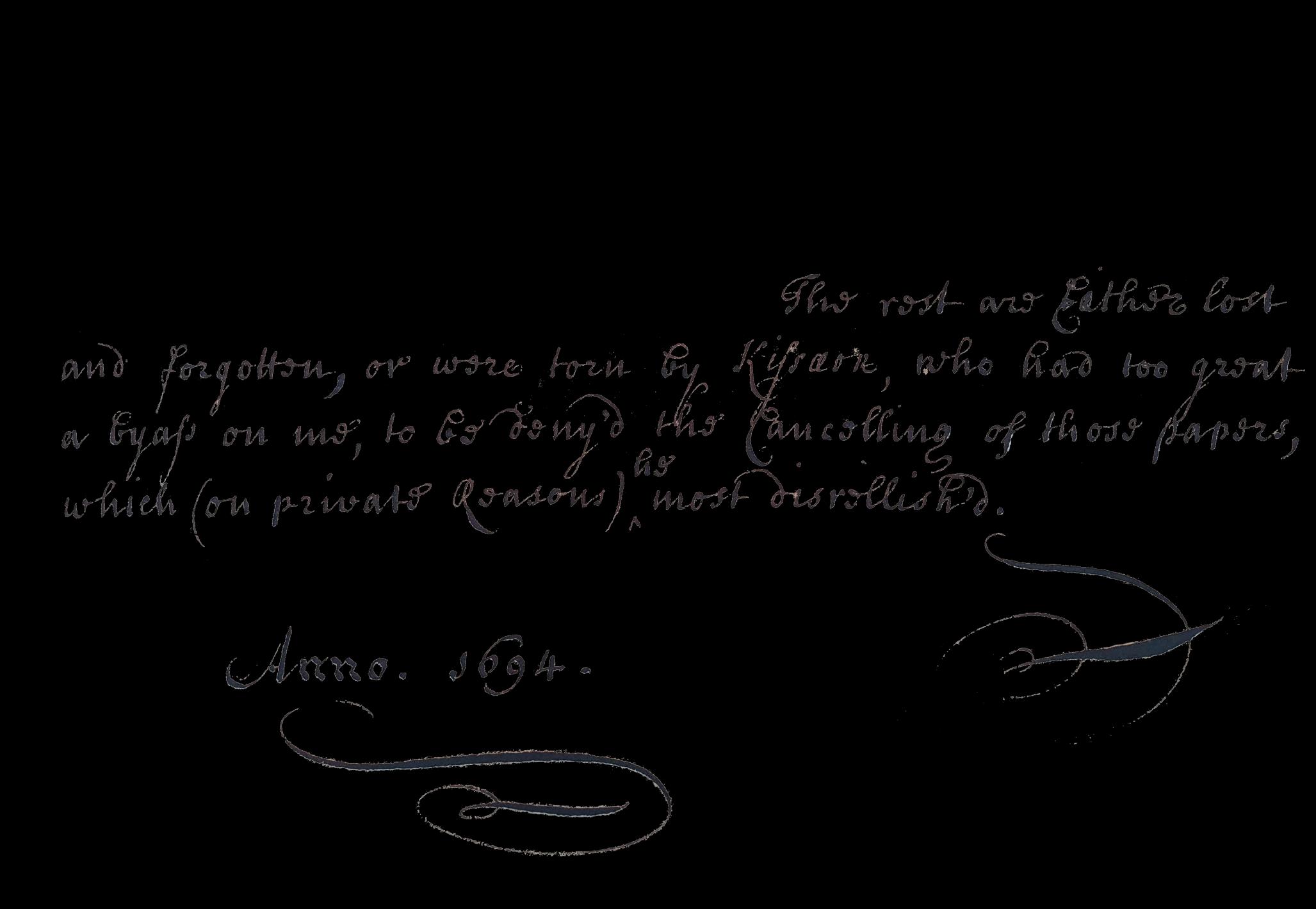

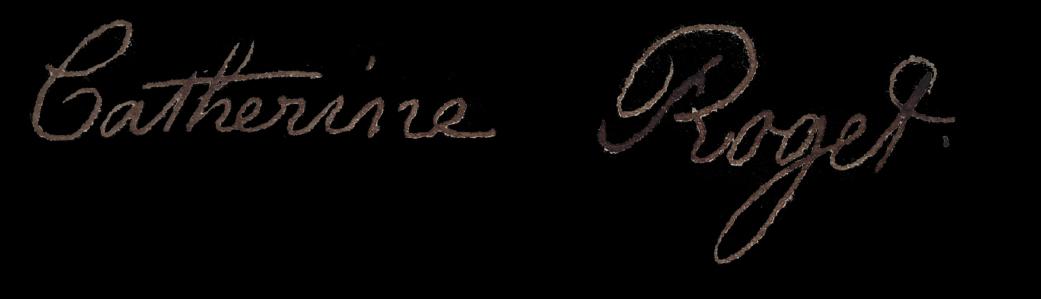

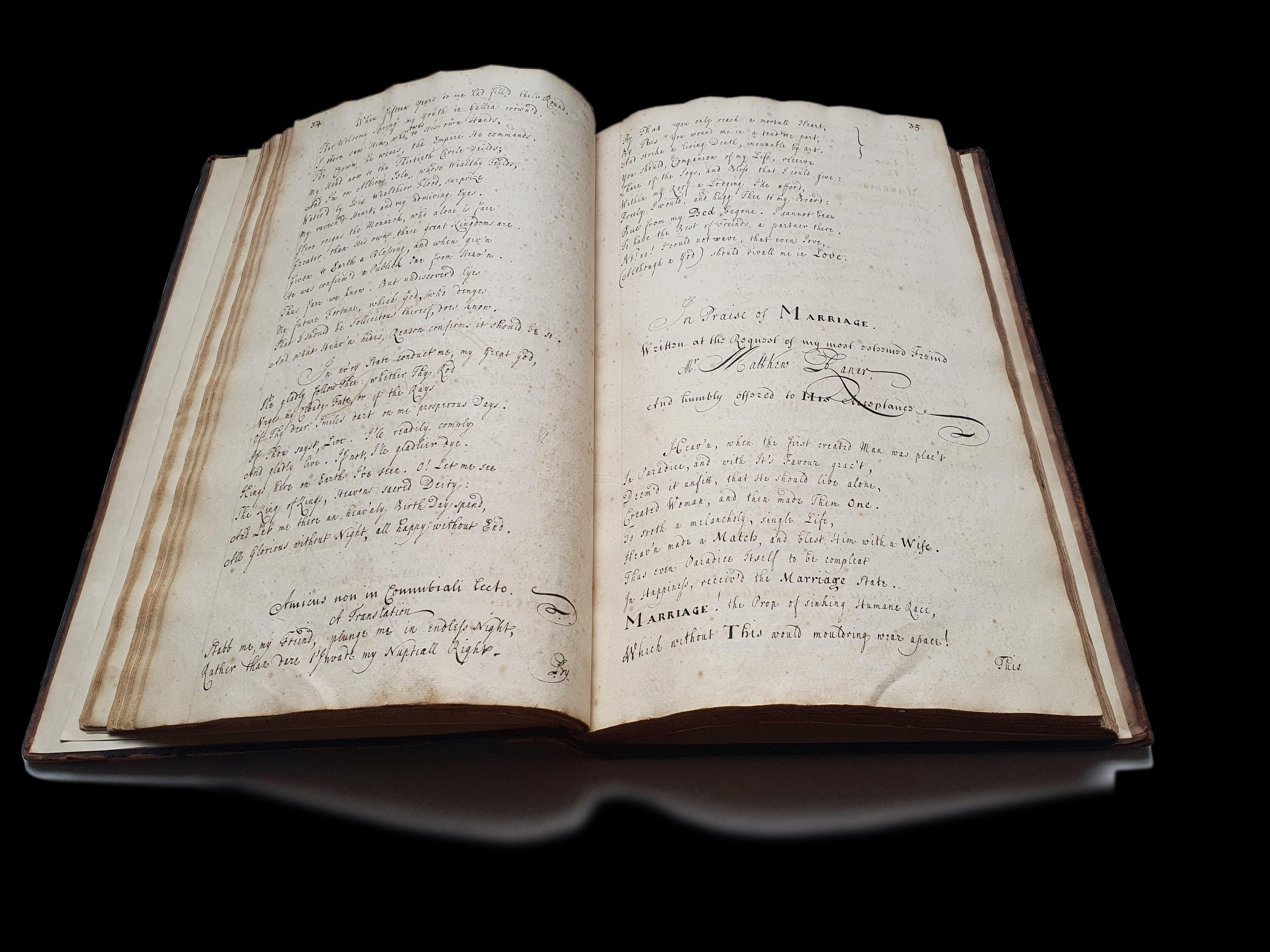

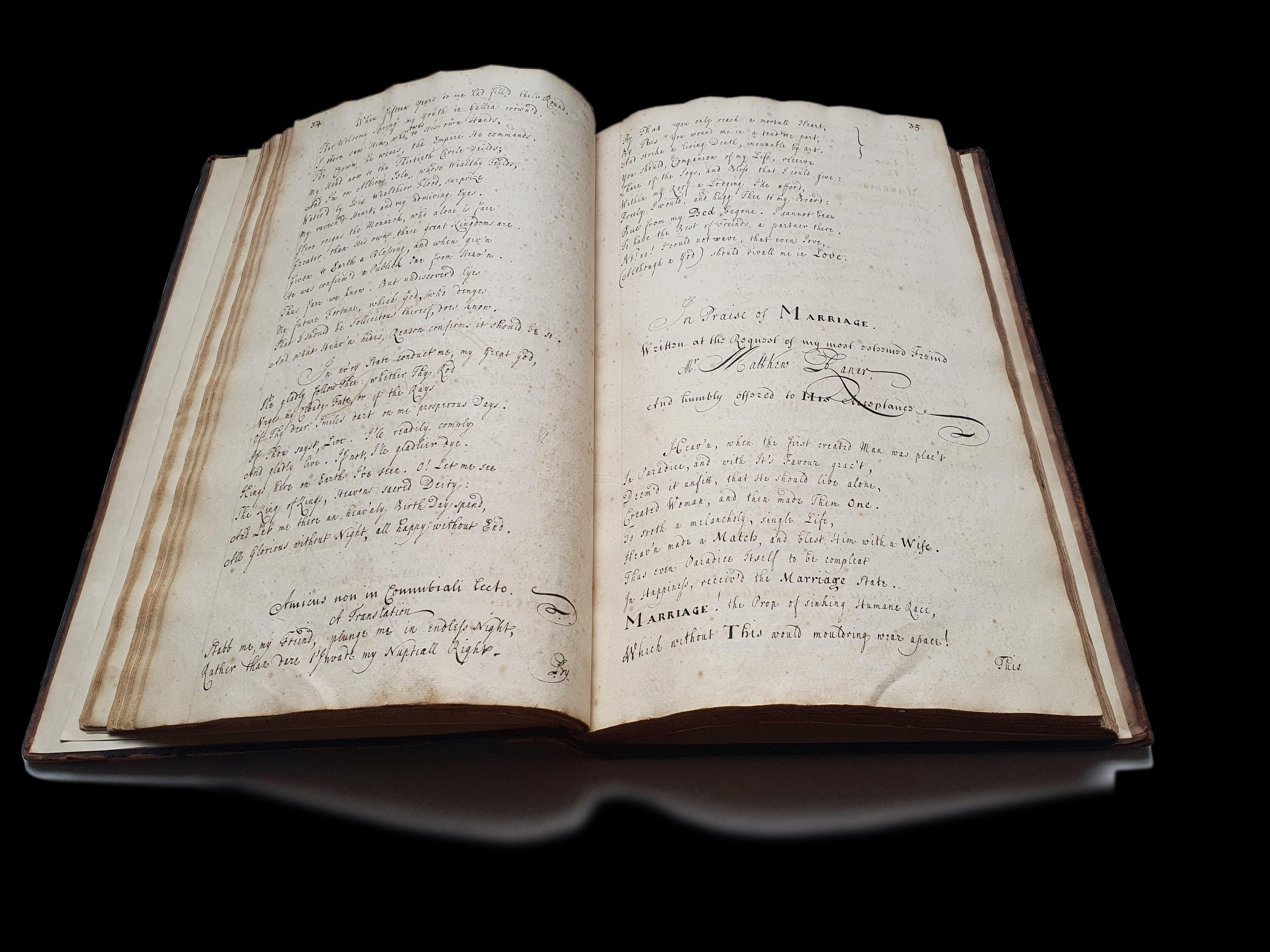

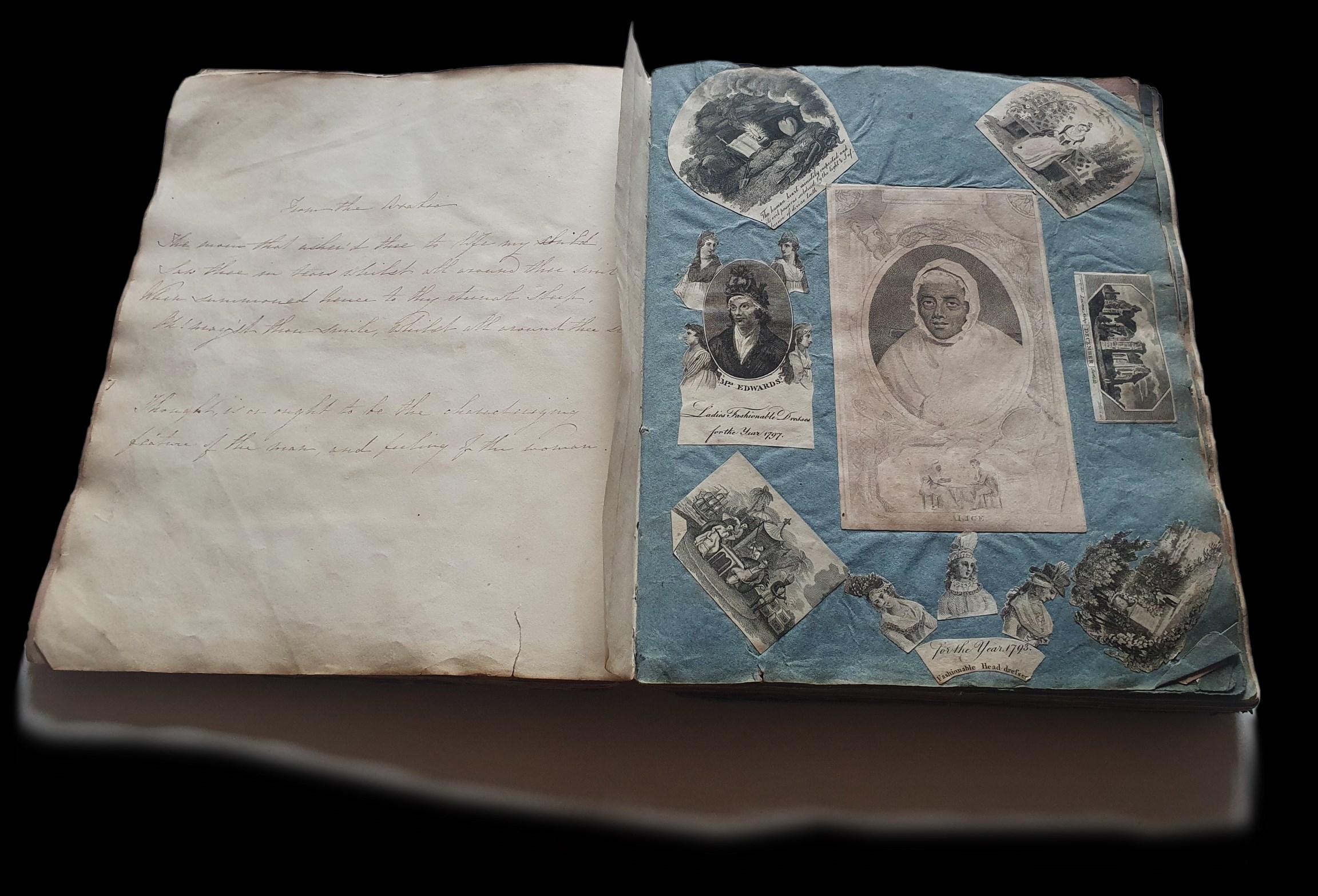

ROGET, Catherine (née ROMILLY) (1755-1835). Two manuscript books of poetry and botany.

[London. Circa 1778-91]. Two notebooks in their original paper wrappers with engraved illustrations.

Catherine Roget [née Romilly], sister of the lawyer and politician Sir Samuel Romilly (1757-1818), was the mother of Peter Mark Roget (1779-1869), compiler of the famous Thesaurus. This pair of manuscript books reflect her interests -educated 18th-century woman – in literature and botany.

More than a decade appears to separate these notebooks, but they share the same watermark, and their engraved covers are extremely similar, raising the distinct possibility that they were bought at the same time. Such notebooks were probably fairly popular in the 18th century, but relatively few have survived; the engraved paper covers gracing this pair have mitigated against their deterioration.

Notebook I. Manuscript commonplace book of literary extracts.

[London. Circa 1775]. Small quarto (195 x 160). 40 pages of text on 20 leaves. Written in a clear, legible hand throughout. Covers dust-soiled and torn at the edges. Watermark: Britannia. Stationer’s notebook, original stitched paper wrappers with engraving to front cover of “A Chart Shewing ye Sea Coast of England & Wales with ye Fortifications Royal Docks Harbours Sands &c. Sold by C. Dicey & Co.” Ownership inscription to upper margin of front cover reads “Catherine Romilly”. The manuscript is undated but presumably precedes Catherine’s marriage in 1778.

Extracts (mostly in French but a few in English) include “En Parlant des Passions” from “Pensées de Ciceron”; passages from “Essais de Montaigne”; “L’homme aprés la Creation” and “Principes de l’homme”, both from “De Mon. De Buffon”; “Menope Tragedie de Voltaire” and “Extracts from the Translation of Chevalies Mehegan’s View of Universal Modern History” “Narblas”. The notebook ends with “Sonnet to the Evening”, which first appeared in print in 1789 as “Sonnet VI” of William Lisle Bowles’s Fourteen Sonnets, which, alongside the work of Charlotte Smith, did much to revive the sonnet form. The date suggests either that Catherine copied the poem into her book leaving her birthname on the cover unchanged or that the poem was circulating in manuscript.

Notebook II. Manuscript entitled ‘Linnaeus’ System’. [London. Circa 1788]. Small quarto (195 x 160). 54 pages of text and illustrations on 30 leaves. Covers dust-soiled and torn at the edges. Watermark: Britannia. Stationer’s notebook, original stitched paper wrappers with engraving to front cover from Francis Barlow’s (1622-1704) edition of Æsop’s Fables. The engraving is the same as those in Barlow’s edition, with text of poem by Aphra Behn, but title “The Sow and Pigs” is within the plate mark which does not seem to be in the early editions, so is presumably a reworking of the original. Ownership inscription to inner front cover reads “Catherine Roget. 1791”. Titles to margins of front cover read “Botany -1787-” and “Linnaeus’ System”.

Catherine’s second manuscript begins with basic “outlines of Linnaeus’s System of Vegetables” (from “I. Monandria. – one Stamen” and “II. Diandria. – two Stamens” through to “XVIII. Polyadelphia. – Filaments in 3 or more parcels” and “XXIV. Cryptogamia. Flowers very small, invisible or not yet discovered”) and then branches out into a more detailed treatment. The next section, “Sketch & Explanation of the Orders of the System of Linnaeus”, elaborates by listing the sub-groups for each (“Monandria” has “1. Monogynia. – one Stamen” and “2. Digynia. – Two Pistils” and so on).. In her next, untitled section, Catherine goes into greater detail and provides examples of plants (e.g “Scabiosa columbraria – Small Scabious”, “Nicotiana Tabacum – Common Tobacco”) which she illustrates with small diagrammatic drawings. Her artwork then blossoms somewhat in three pages of drawings of indigenous plants (“Wild Speedwell”, “Blue Monk’s hood” etc), which she has sketched in pencil and then drawn over in ink and heightened in watercolour.

Following this brief interlude of individuation, she returns to classification, with details of “Leaves as to figure” in 62 leaf forms from “Orbiculatum” to “Teres”. Under the heading “Stalks of Flowers” she includes examples and brief details (“without an odd feuillet or having the secondary pinnated again & these last not terminated”, “Spatulated or roundish above with a long linear base”), and similarly, of Fructification” are accompanied by sm in pen, some with watercolour washes.

Notebooks of this kind and vintage offer many attractions – the glimpses into a young 18th-century woman’s intellectual life, the uses and adaptations of published material by their contemporary readers – and each also has its own particular appeal. In this case, Catherine Roget has, in her Linnaeus notebook, created a personal reference work which, though by no means unusual in itself, has resonances with the renowned reference work that her son was soon to create.

SOLD Ref: 8122

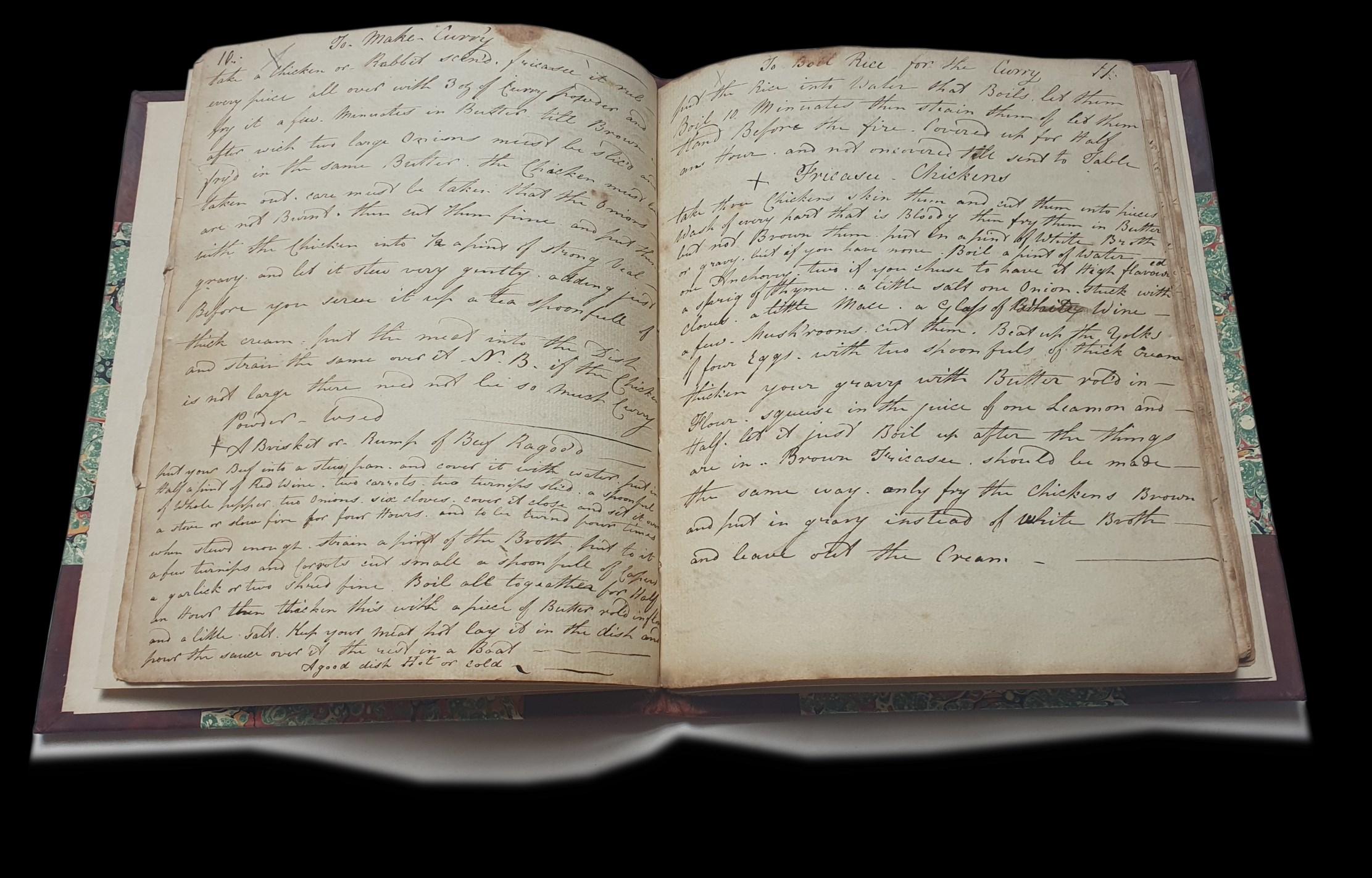

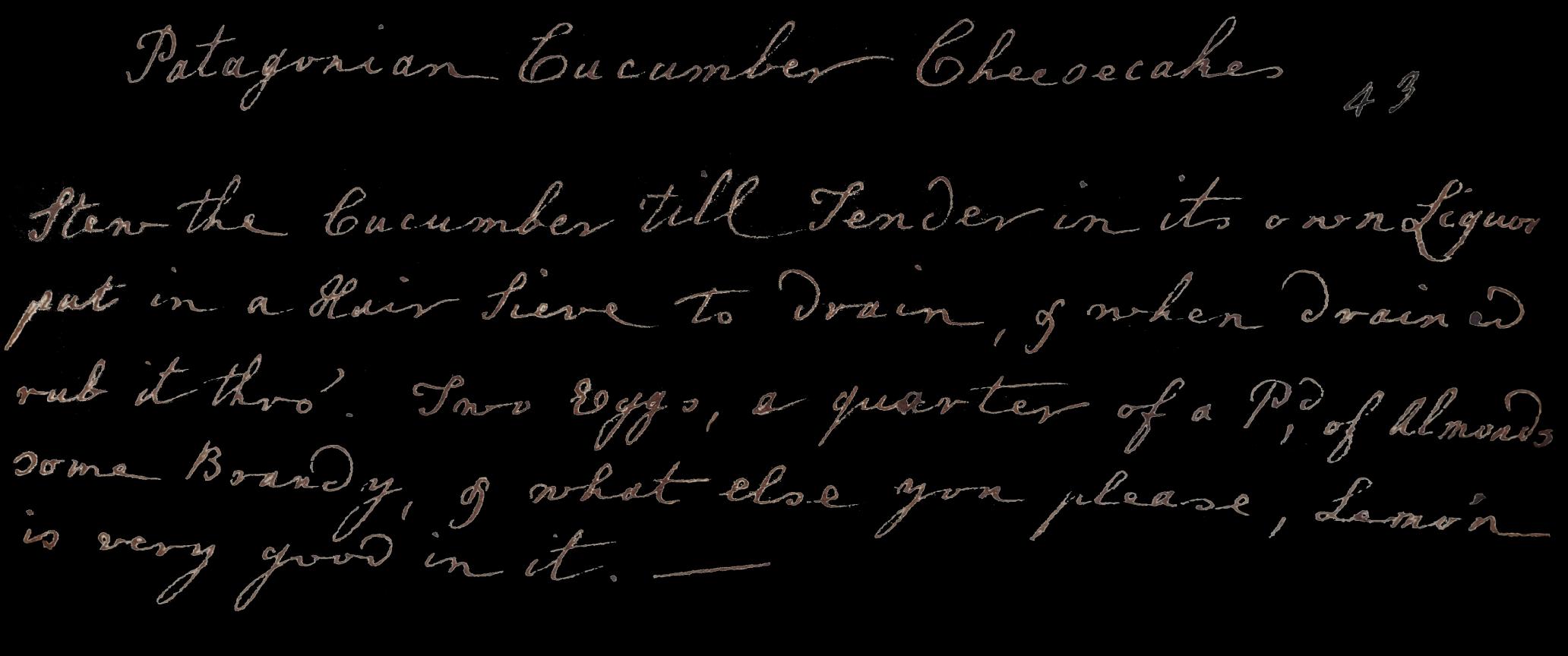

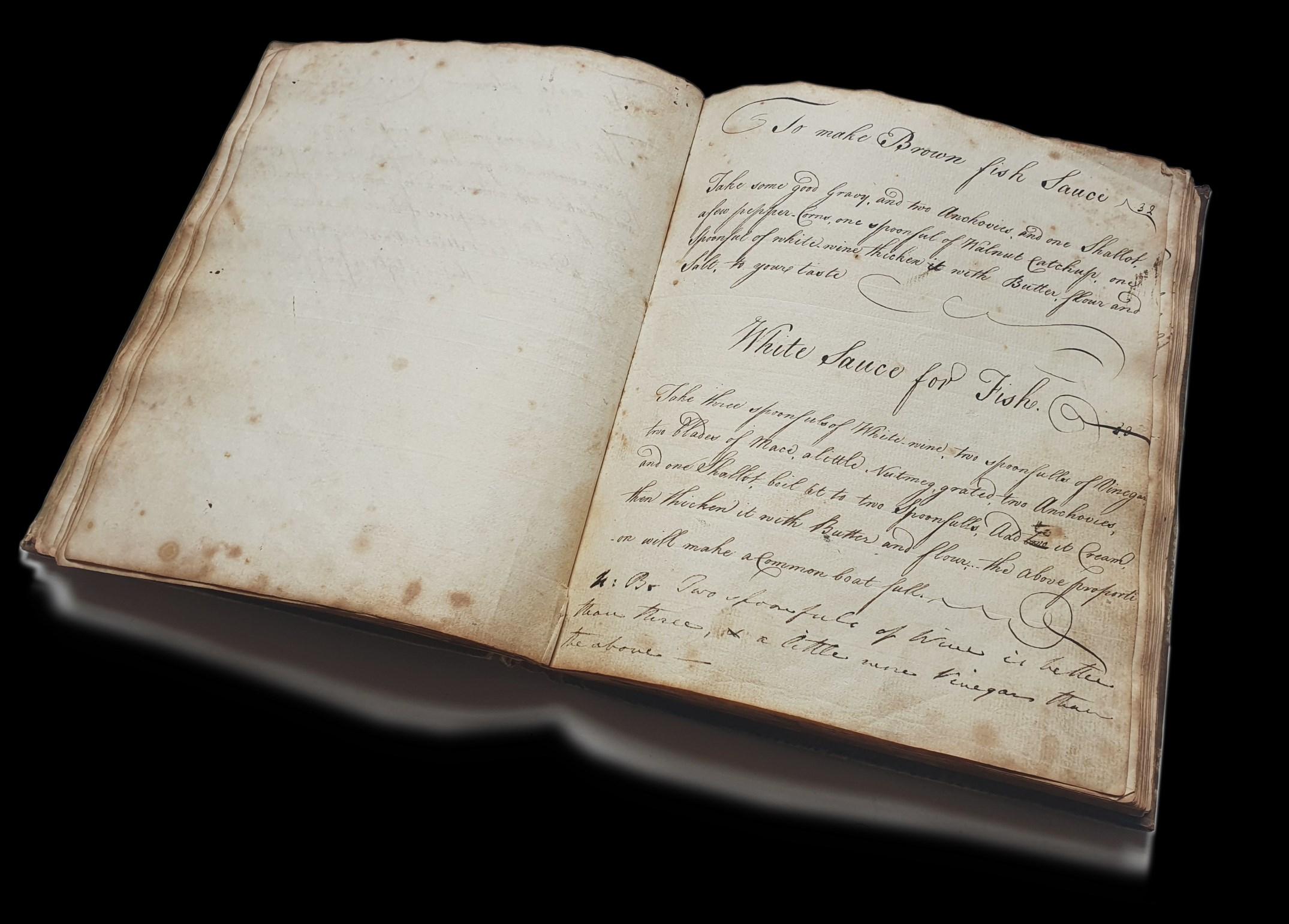

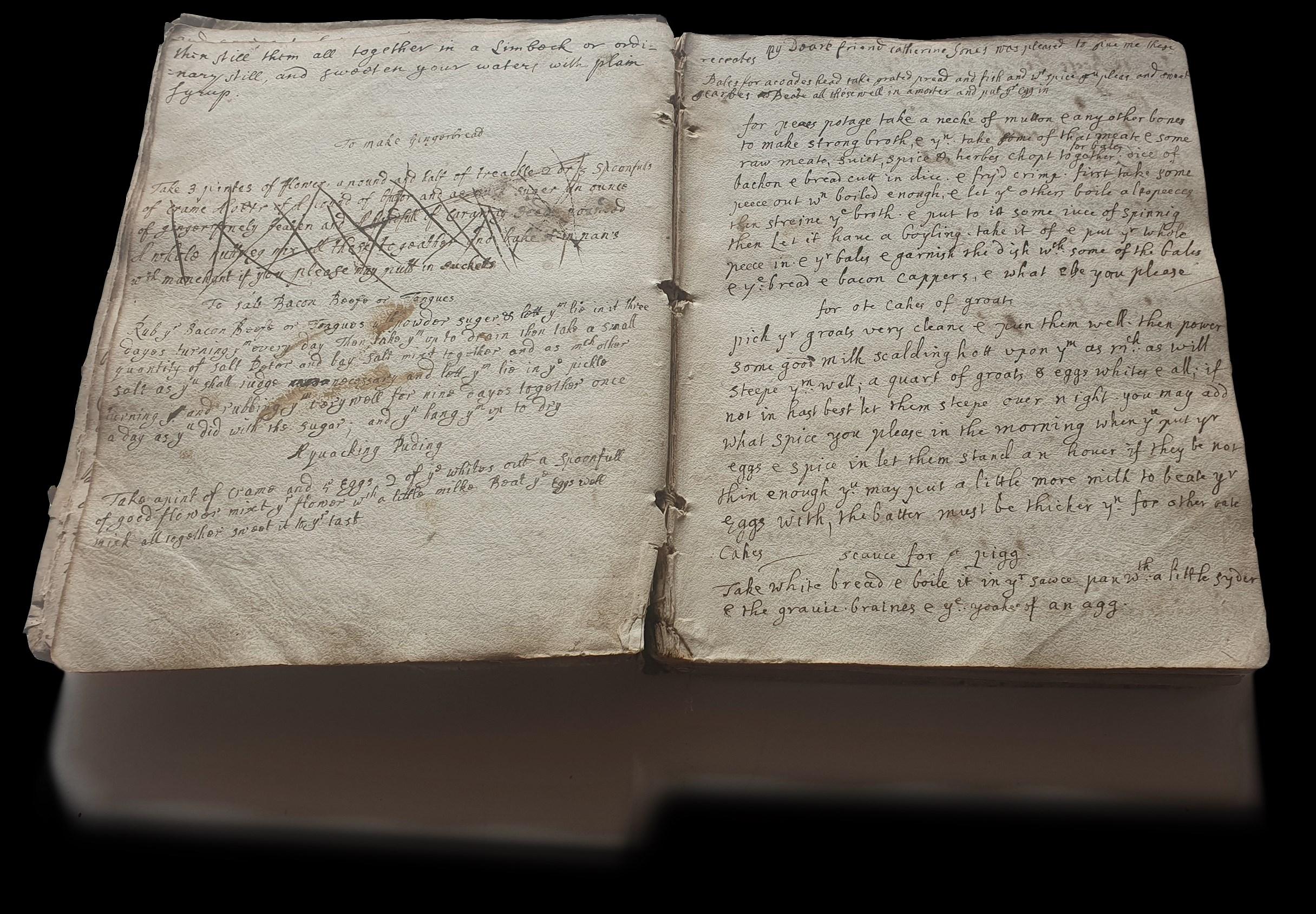

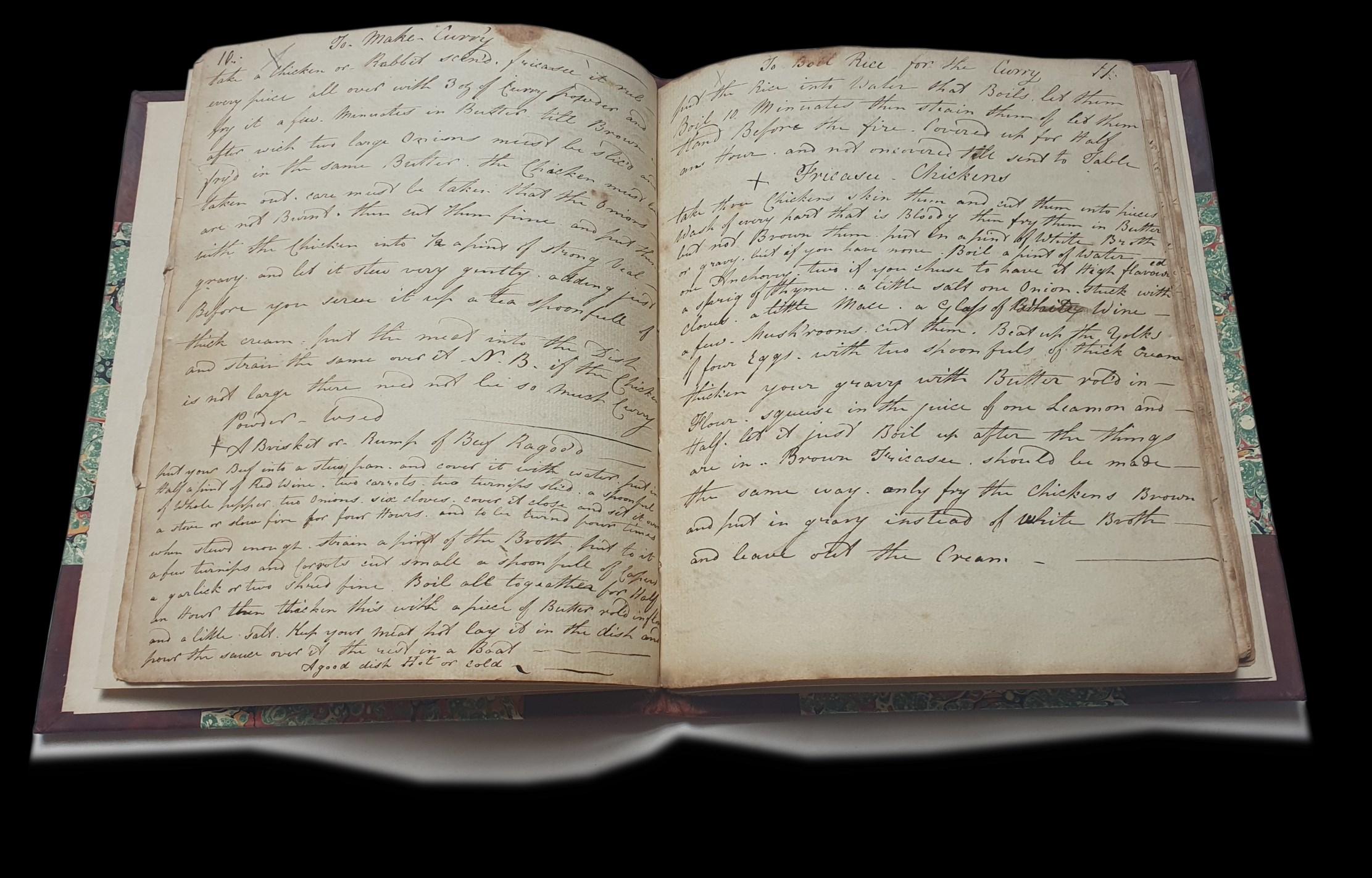

3. THERE WAS A GOOD COOK FROM ...

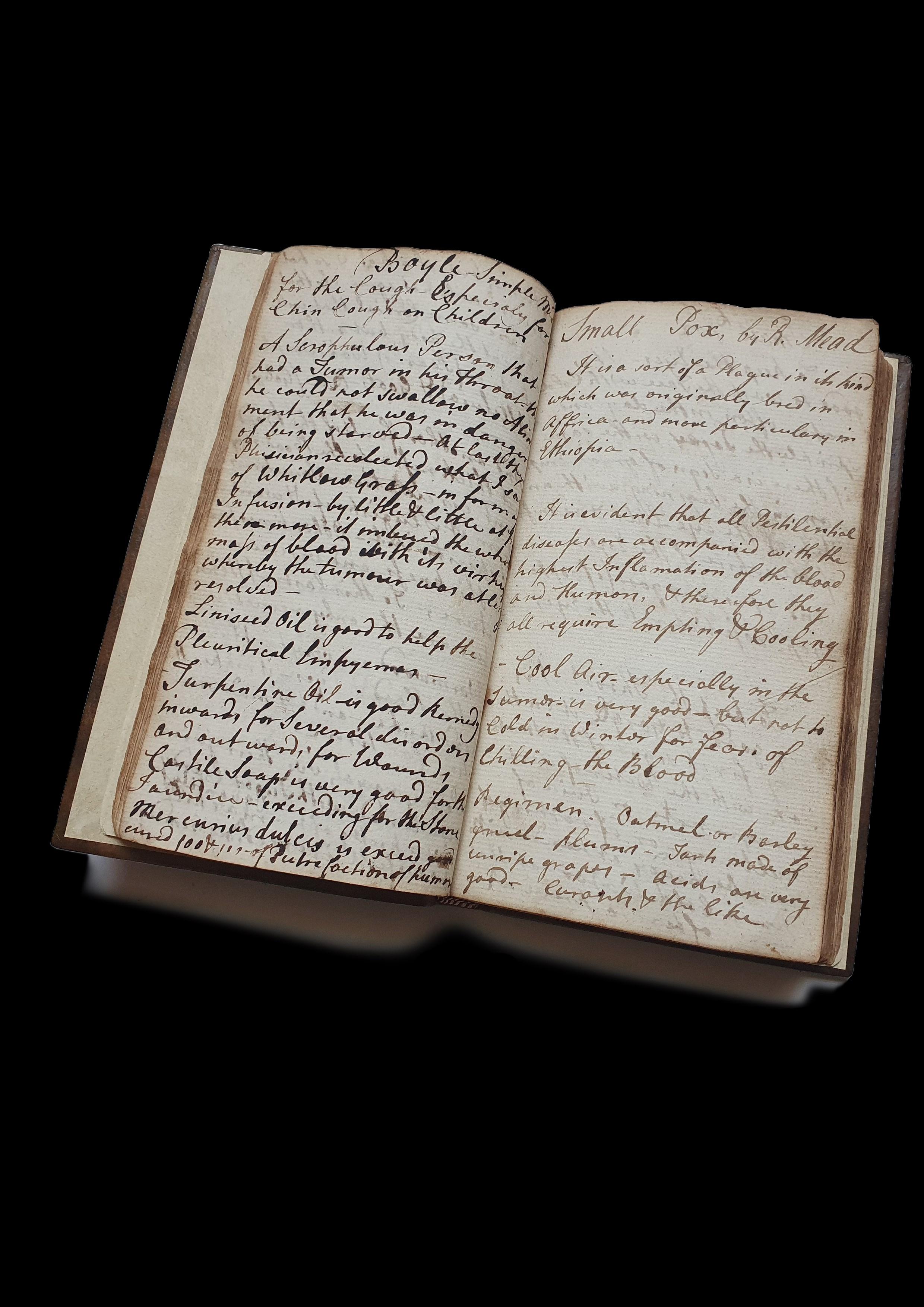

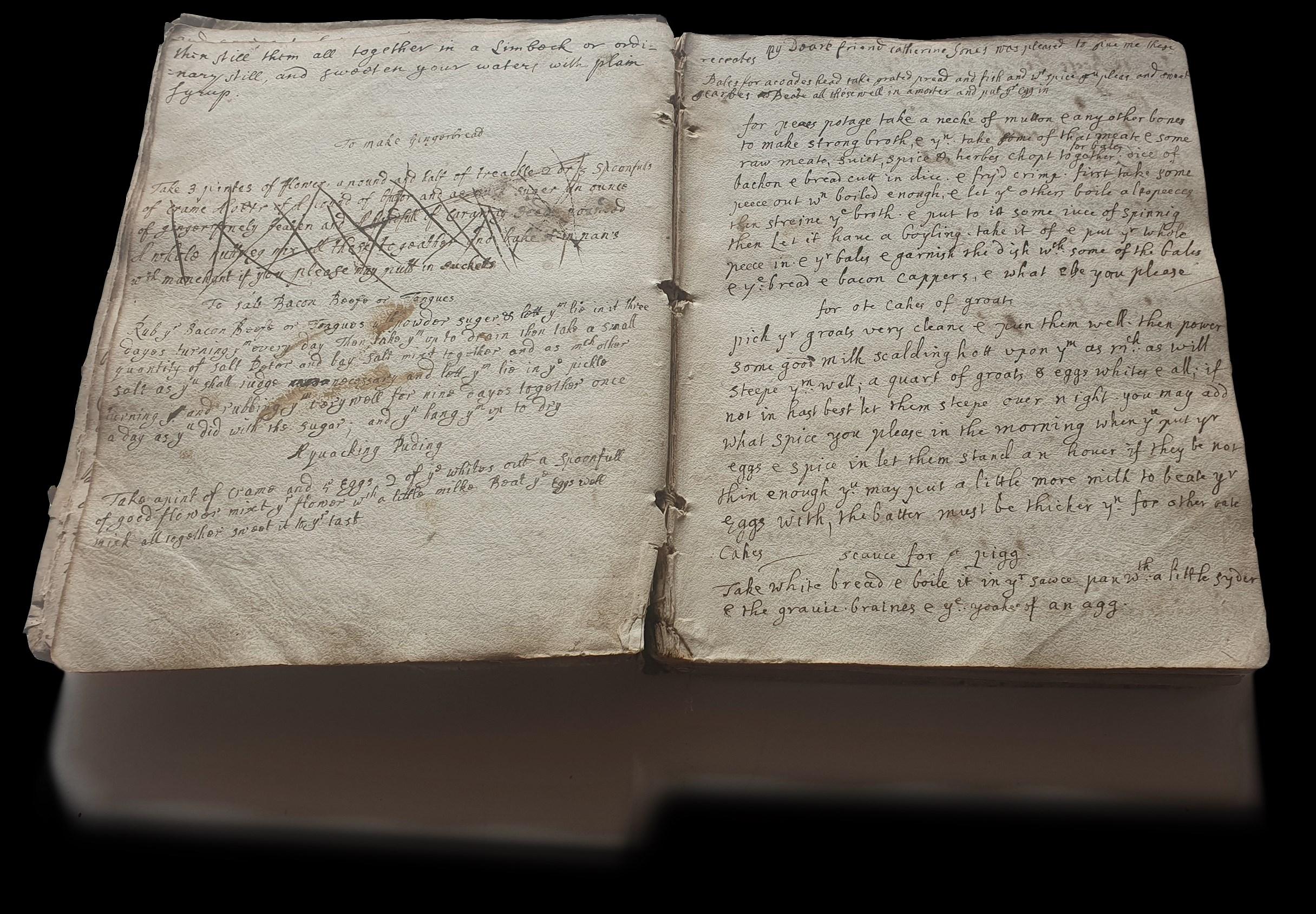

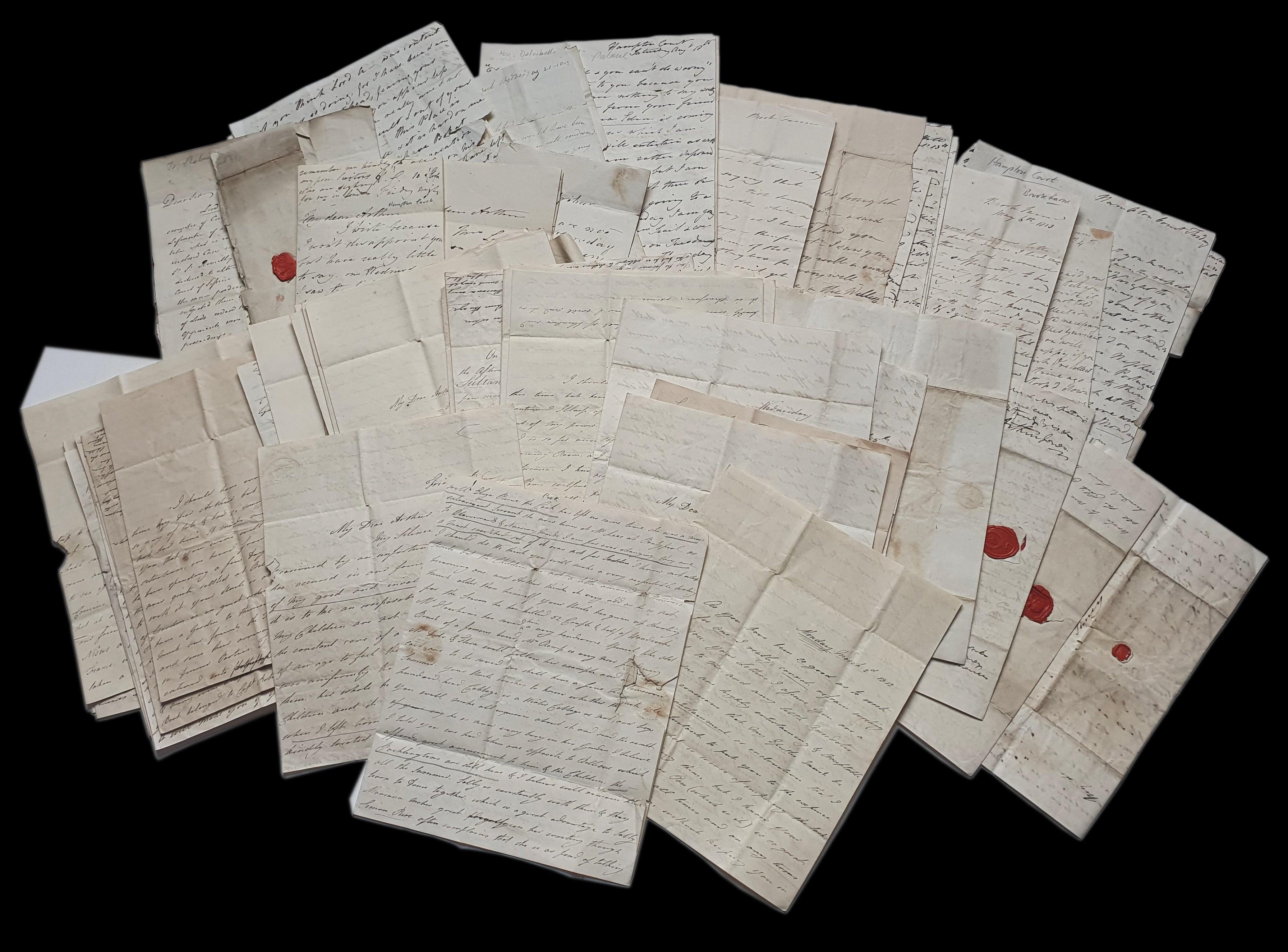

[UNDERWOOD, MAUNSELL, & CASWELL FAMILIES] Two Irish manuscript recipe books, together with over 70 looseleaf recipes and a scrapbook.

[Ireland, Limerick and Portarlington. Circa 1732-1860]. Two quarto volumes, together with looseleaf recipes and a small octavo notebook.

¶ This multifarious group of household remedies and recipes is the product of several generations of the Maunsell and Caswell families, who were related by marriage. The earliest manuscript was compiled for Mary Underwood, who does not appear to have been a family member, but who certainly lived in the same geographical area, so was perhaps a servant to the Maunsells.

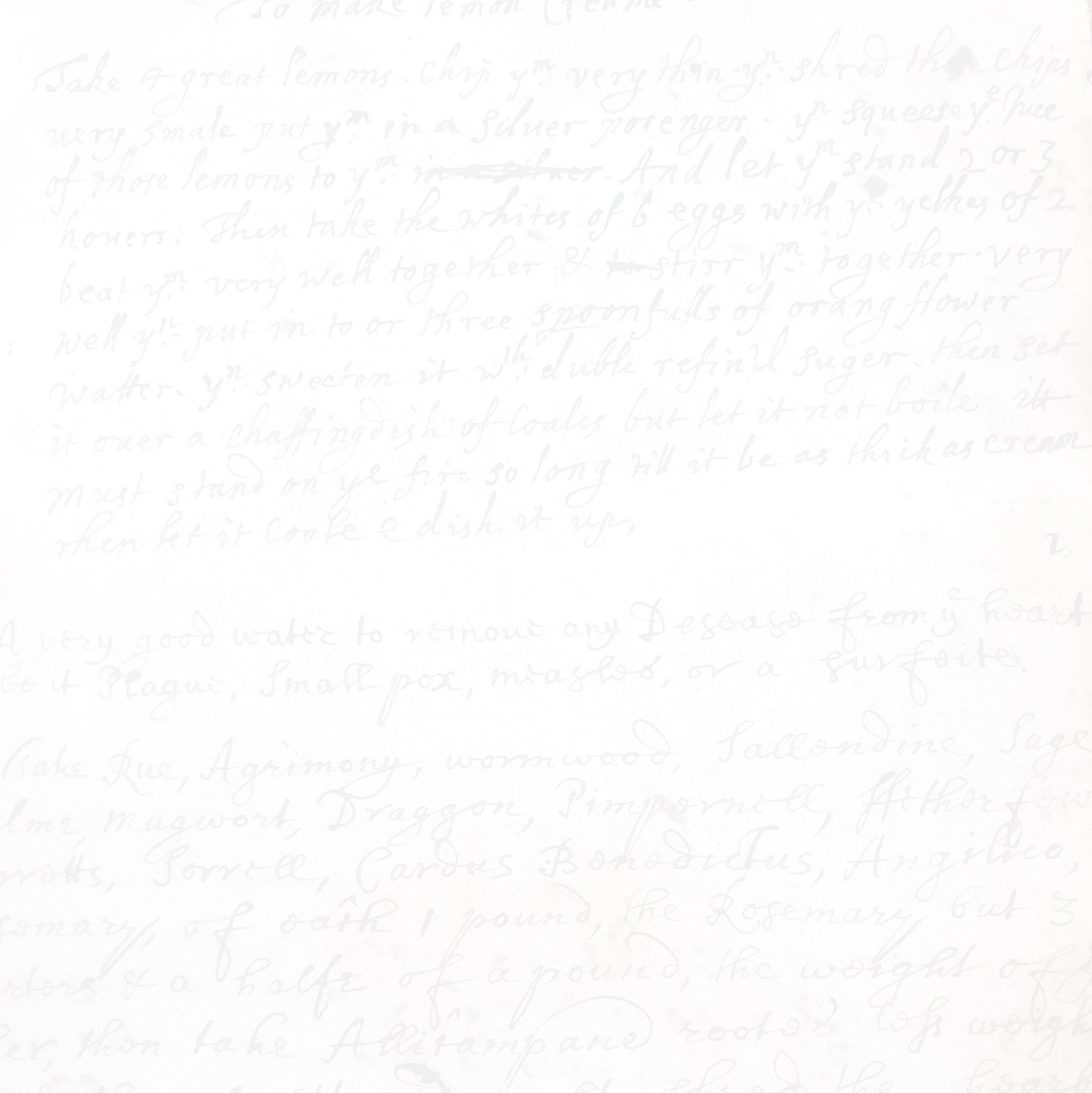

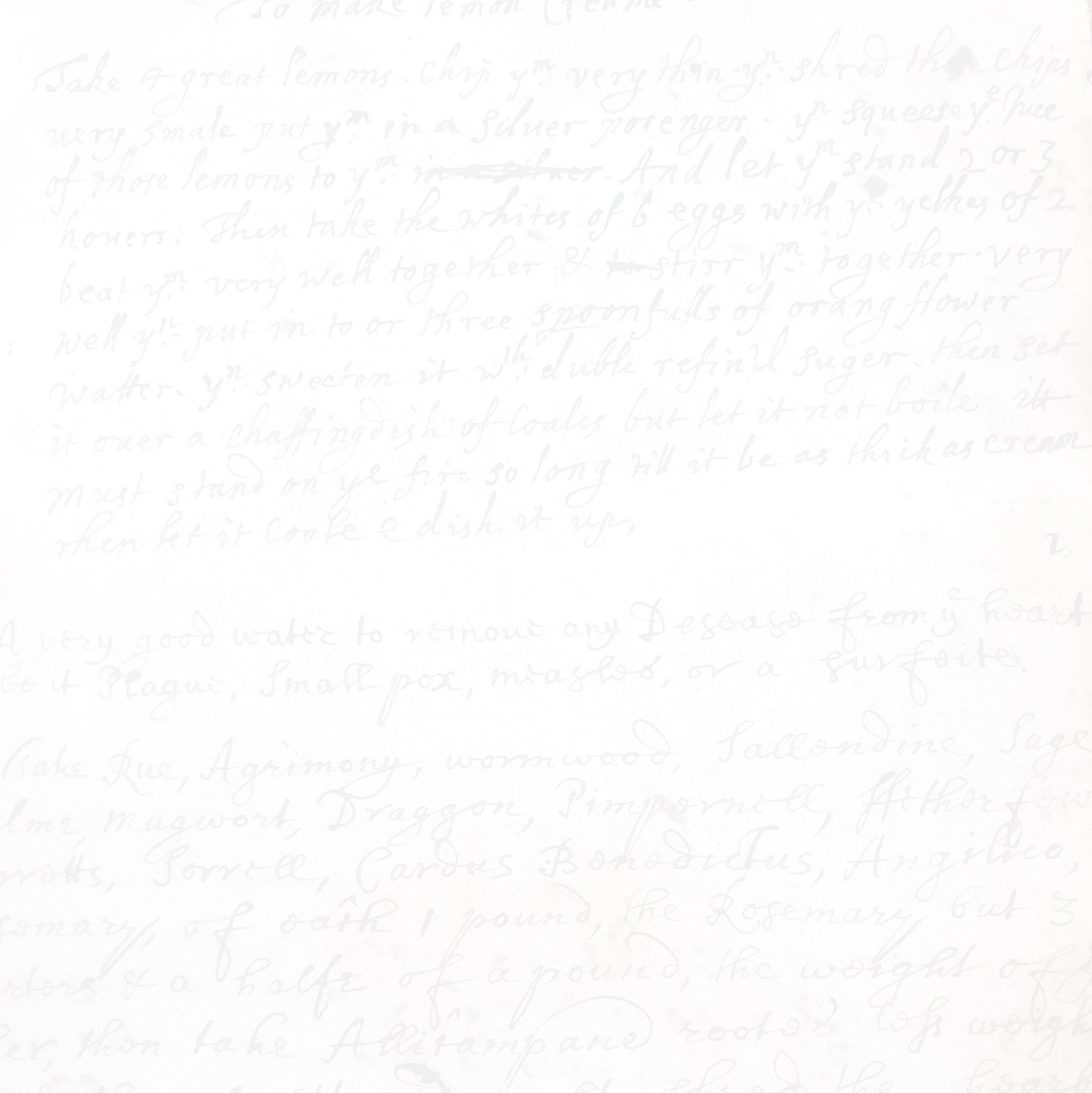

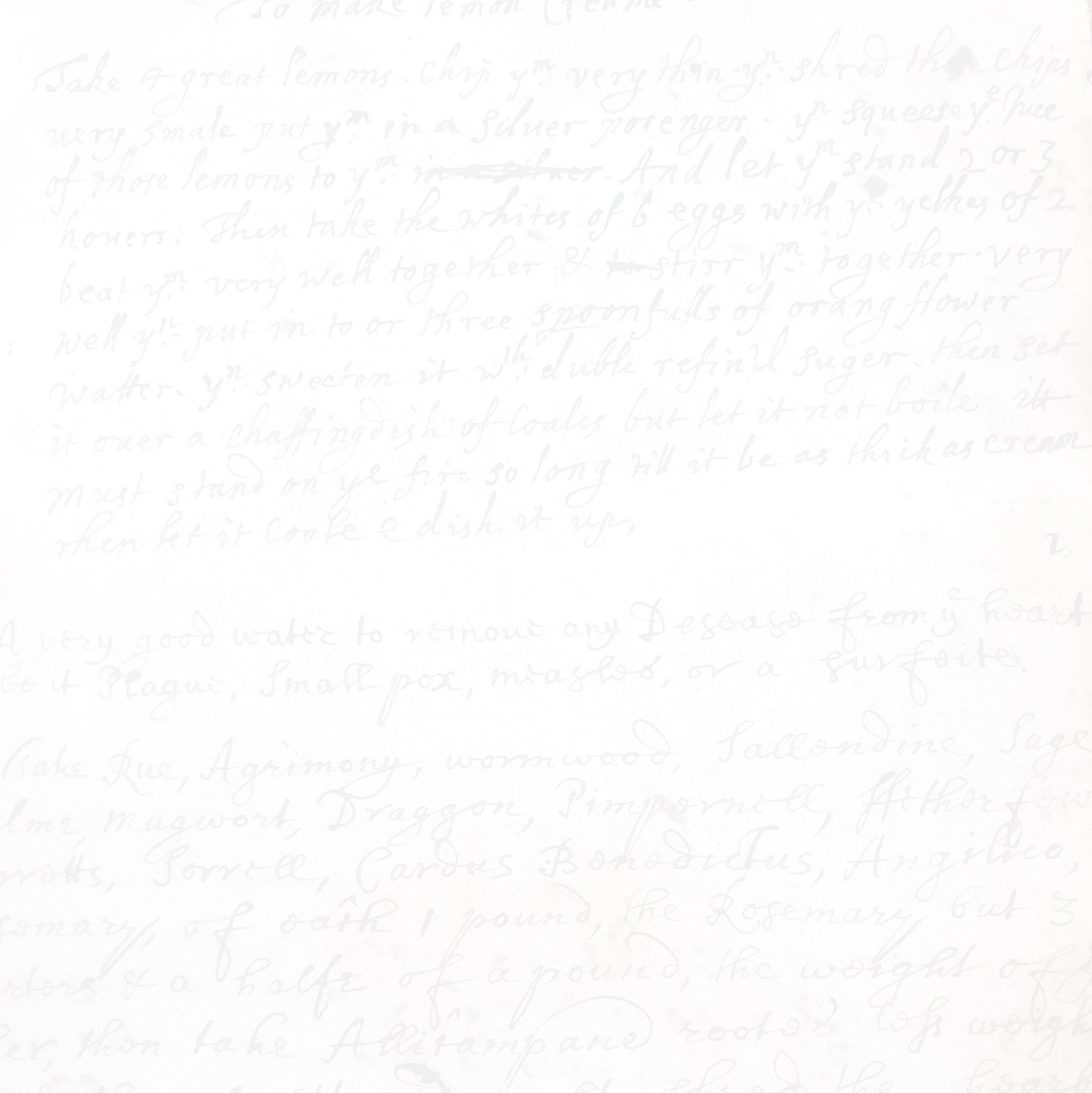

[1]. [UNDERWOOD, Mary] Early 18th-century manuscript of culinary and medicinal recipes entitled ‘A book of Receipts’.

[Ireland. Limerick. Circa 1723-3]. Title page and 27 text pages (mostly to rectos) in three hands on 24 leaves, 37 blank leaves, some pages excised and missing. Contemporary vellum, worn and soiled, missing lower section of spine, text block loose.

¶ Three hands are evident in this manuscript, the majority of which presents remedies, along with a few recipes for wines and cakes. The first page appears to introduce these three scribes, but also introduces a note of confusion since these are all rendered in the same hand: “A book of Receipts belonging to Mrs Mary Underwood Limerick June the Seventeenth 1732 / Written by James

Fitzgerald In the year of our Lord 1733 / Mary Underwood her book 1733”.

Conditions needing alleviation include “The Gravel”, “for Cough of Cold”, “Erisipelus” (a form of skin infection), and “Apostemes in the Ear or Ulcer” (with a further remedy for “Noise in the Ears” – perhaps tinnitus – “of which a Gentleman who was hysterical was Cured”

Depending on their ailment, the sufferer may be subjected to a treatment involving “horse Dung”, “Motton Dripping or hogs Laurd”, “one Gallon of white Snails” or “Eartworms cleansed”; or they may get off lightly with a

remedy containing “Nutmeg”, “Canary Wine”, “Myrh, Alloes, and Saffron”, “Rosemary flowers”, “feneegreek”, or “Lisbon wine” If requiring “A Receipt for the Dropsy”, they could expect something containing “2 handfulls of Ground Ivy, a quarter of a pound of the fielings of Steell, half a pound of Rusty Iron, The Peilings of 12 Civell Oranges”; or, in the case of “the “Mithridrate 20 grains and Virginian Snake weed in fine powder 13 Grains”.

Instructions and doses tend toward the specific: the somewhat ferrous remedy above for “the Dropsy” directs that one should drink “a pint of it in the morning & a pint at noon – a pint at Night milk warm”, while the “Receipt for the Scurvy or Itch” reassures us that “The Ointment may be used on the belly and Stomack and every where for it is Safe”, but adds that “it is troublesom for you to make, the Apothecary hath it ready made”

Such remarks give clear evidence that the manuscript was both created and used with a degree of first-hand experience: a recipe for “Marmalade” advises that “it is better to boyle [the oranges and rinds] up often Then to add, so much Sugar at a time”. There are endorsements, too, such as “These three last rects are aproved of & given for choice” and “It’s an infallible receipt for Consumptions, it is very good for ye Cholick in Stomack it cures the Jaundice and Dropsies” – as well as the familiar note of approval, “Probatum est”.

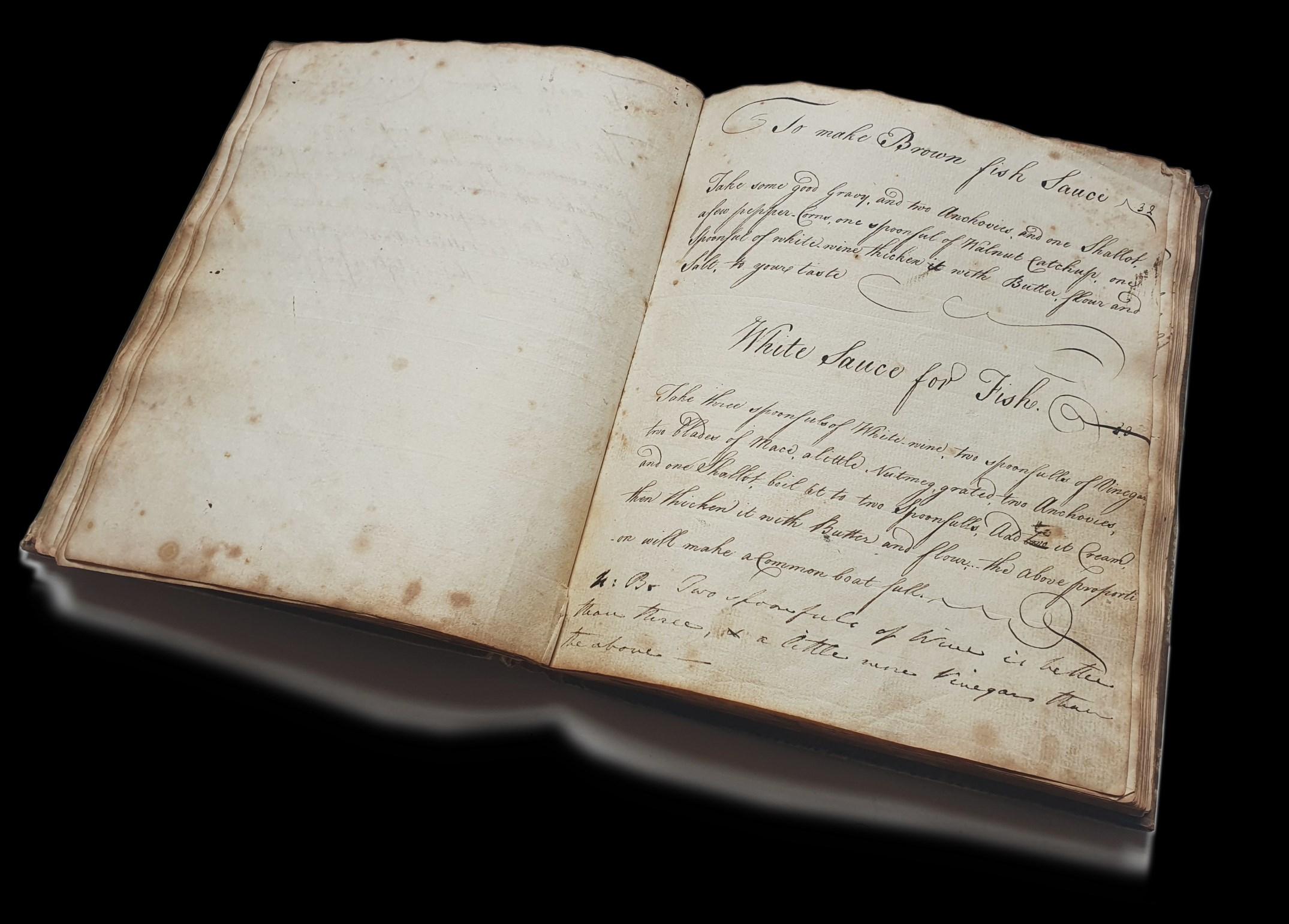

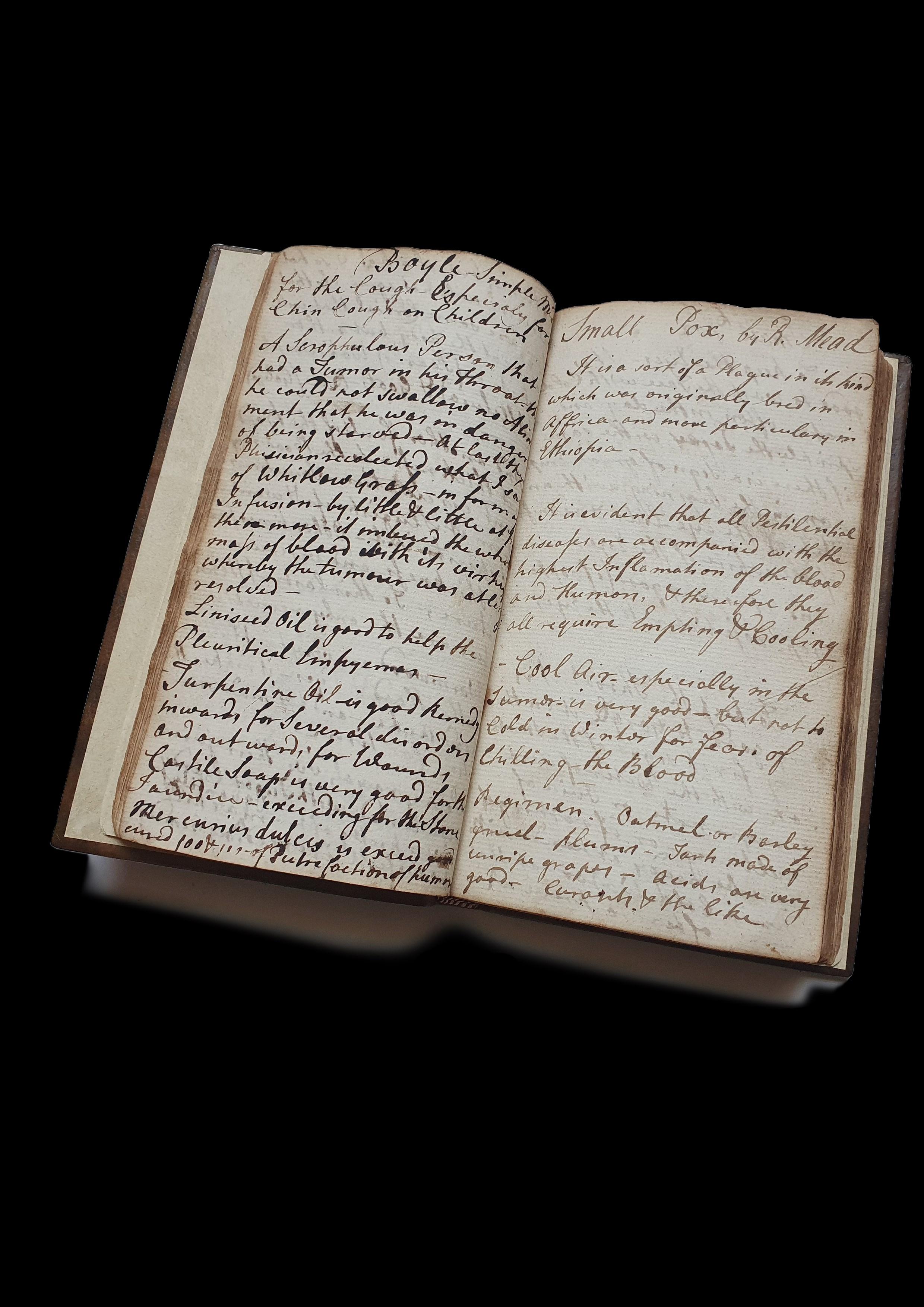

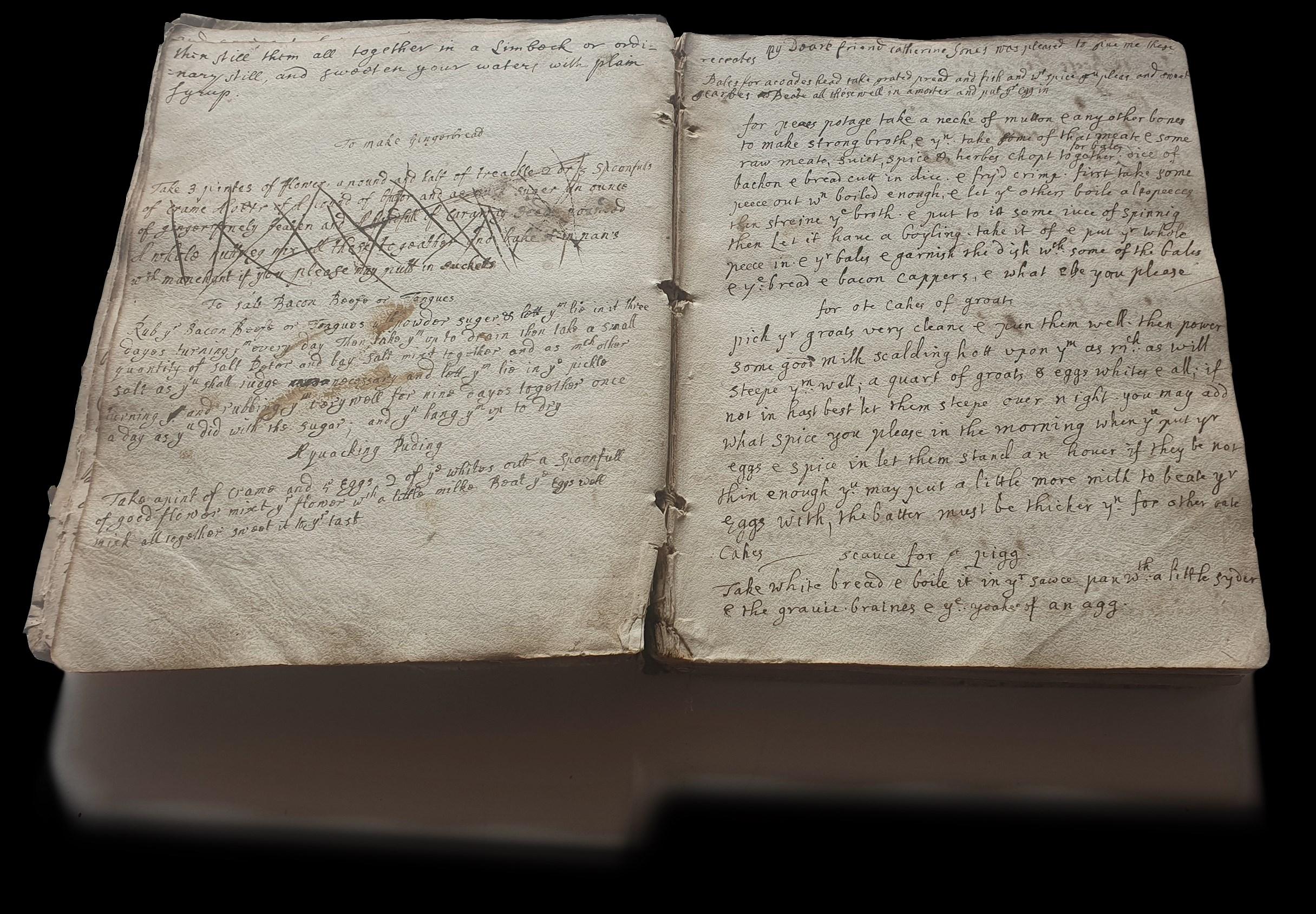

[2]. [MAUNSELL, Richard] Late 18th- to early 19th-century manuscript book of recipes and remedies. [Ireland. Portalington. Circa 1790-1810.] Pagination [6 (4, index; 2 blanks)], 98, 105-119, 5 blank leaves; 13 at opposite end. Contemporary calf backed marbled boards, very worn, lacking spine, text block loose. An inscription to front free endpaper: “Rich. Maunsell Portalington March 3d 1807”, written in a different hand to that of the earlier sections of the manuscript.

¶ This second volume was probably commenced later in the 18th century. It is written in a further two different hands, the second of which belongs to “Rich. Maunsell Portalington March 3d 1807”. The character of the manuscript is very different, in several ways: recipes vastly outnumber remedies, attributions are much more in evidence – indeed, some entries are grouped by attribution, suggesting that they have been copied en masse from collections of friends and acquaintances – and a few recipes have an international flavour, demonstrating how well connected many families were in Ireland.

The manuscript begins with an index of recipes, before an initial batch headed “Mrs Massy’s Recits” (“To make an EggCheese”, “To make Rice Pancakes”, “Dr Smyth For a Cough”, etc); and she makes further appearances later, with the likes of “Sago Pudding” (p.62) and “Rice Jelly” (p.82). Elsewhere, another group, numbering over 15 recipes, is headed “Mrs Verckert’s receits”, and includes “Naples Biskets”, “The Right Indian Pickles”, “To Collar Cow Heals”, and “Excellent Saffron Cakes”. Later on, “Mrs Leslie’s Receits” showcase that lady’s strengths in preserving fruit (“Raspberries”, “Golden Pippins”, “Oranges Whole”, “Apricots – N:B: The skins make a pretty little Tort”).

The network of recipe exchange broadens with every page, as we encounter “To Pickle lemons – by Mrs Moore”; “Pickled Salmon + by Mrs Mict Stretch”; “Wallnut Catchup – Mrs Purdon – very fine”; “Queen Cakes – Mrs Widenham”; “Petty Pattyes – Lady Rothes”; and so on. The recipe: “Mrs Monsell – Brandy Peaches” presumably refers to Mrs Maunsell, suggesting that the unattributed hand is that of a servant. Remedies, too, are endorsed through attribution, often to medical sources: “Doctor Frends receit for a sore Throat”; “Doctor Meads Elixir of Rhubarb for the Gout”; “Dr Ormonds receit for Plaister to Ripen & draw a Sore”; or to redoubtable-sounding authorities such as “Mrs Clampett for the Evil”.

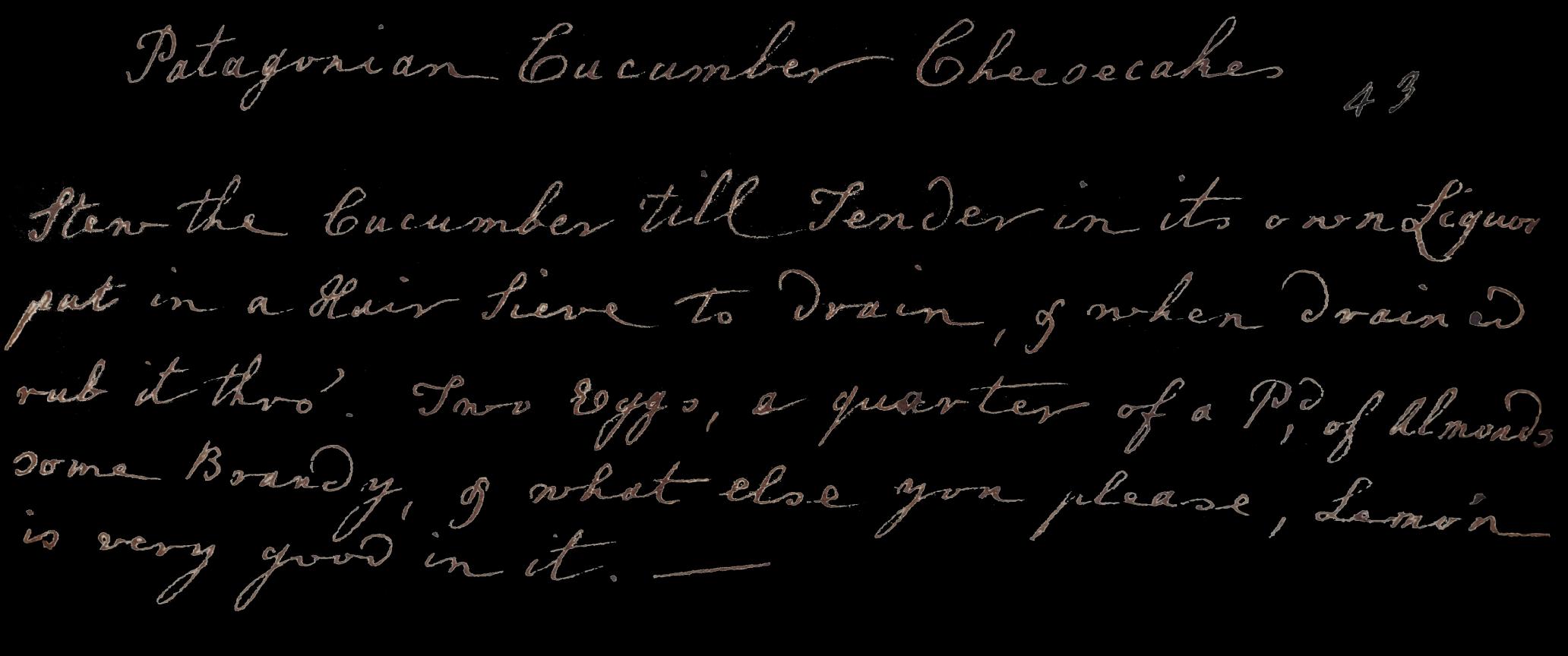

Alongside the kind of dishes expected of any recipe collection (“To make Sausages”, “Catchup”) and local specialities (“To Bake Salmon – Limerick”, “To make Irish Plums”), there are a few pleasingly named confections: “A Hedge Hog” turns out to be an almond cake with “2 Currants for eyes”; and “A What Madam” involves the combination of “Curd of a Gallon of milk, ¾ of a pd of butter, 2 grated Biskets”. The geographical reach extends a little with “Olio, a French Dish” (“Cut 5 or 6 chickens in quarters, 3 pints of Green peas, 2 large lettuces, 6 Artichoak bottoms, & a little spearmint shred small”), “Naples Biskets”, “Dutch Wafers”, “Prussian Puddings”, and “German Puffs – Mrs Gough”, and journeys still further to include “The Famous American Receipt for the Rheumatism” and “Picklelilloes – Indian”. Another section presents dishes from “Mrs Charles Smyth”, including the far-flung “Antigua Pudding”. Outlandish in another sense is the disturbingly named “The Leg of a Negro”, which actually features “a leg of tender Pork, cut like ham [...] seasoned with Claret or Port” – but which betrays all too clearly the cultural norms of some members of society, even at a time when the abolitionist movement might have given them pause for thought about such terminology.

Like the first, this volume bears signs of having been well used. Notes have often been added, either as simple encomia (“Best Boiled Almond Pudding” is pronounced “Extream good”; “An herb Soop” has been “marked, much liked”) or as qualifying remarks (“Orange Tarts […] This is for lids for them or any other fine thing, but it is too rich for side Crust”) or to suggest adjustments (“Potted Woodcocks […] If you have no oven, put them into a tin pan with fire under & over them, that the birds may do gently”; “Live for Ever […] N:B: This is very hot, & perhaps less Ginger would answer better on account of its great heat, cut the Lozinges small”). A recipe for the popular “New College Pudding”, which appears to be a manuscript circulated version, is so brief as to suggest familiarity, and includes a couple of amendments that indicate active use and experimentation.

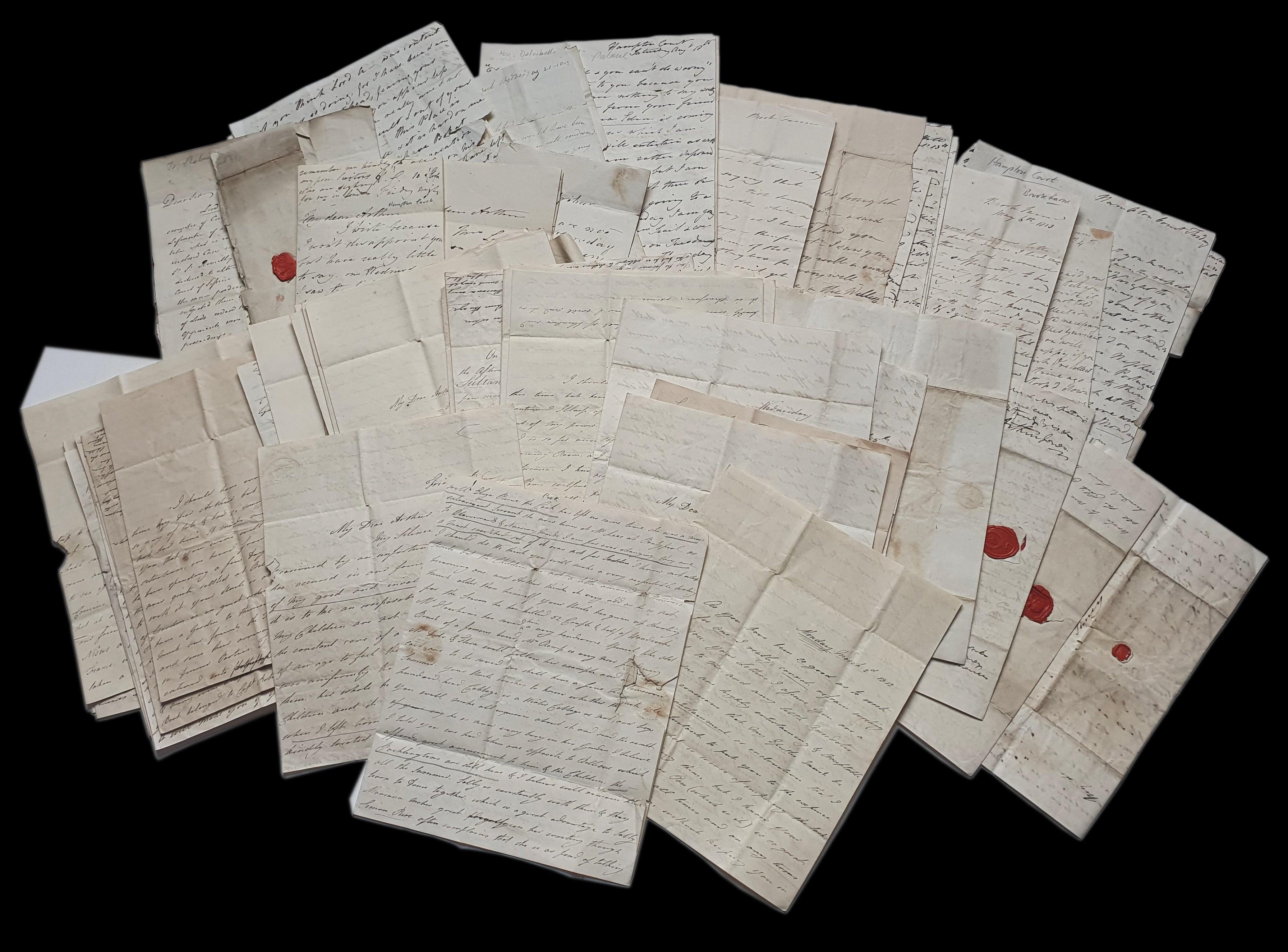

[3]. [VARIOUS SCRIBES]

[Circa 1780-1860.] This manuscript contains upwards of 70 loose recipes and remedies from various correspondents in many different hands, a few addressed to members of the Maunsell family.

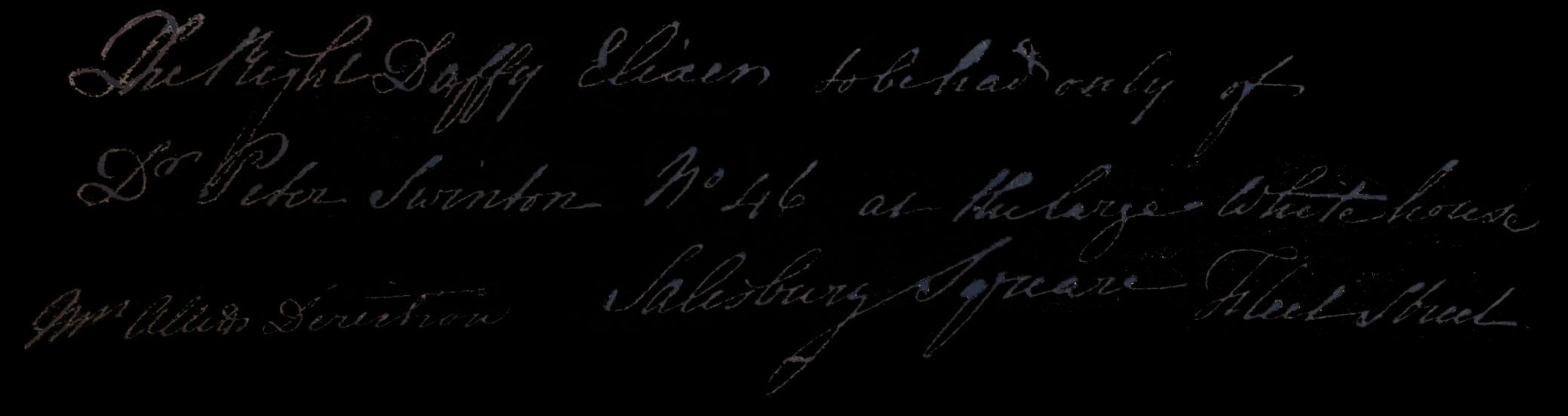

¶ Contents include “Dr Quirk’s recipe for Flux”, “To make a mackerony Dish” (addressed to “Miss Boswell”), “To make Daffy’s Elixir”, “A Cure for the Hydrophobia. Decr 13th 1807”; and “Spanish Flummer” (for which you should “always use silver spoons”). These copious loose-leaf recipes and remedies demonstrate the fluid nature of manuscript culture. Crucially, they provide evidence that this collection was, in no small part formed through a lively social interaction whose alliances were bonded through manuscript recipe exchange.

[4]. [CASWELL, Samuel] Scrapbook of newspaper notices and handwritten letters. [Ireland, Limerick. Circa 1840-90]. Octavo. Card covers. Armorial bookplate of “Samuel Caswell / Blackwater”.

¶ The chief value of this scrapbook – which contains clippings from Irish and English newspapers (Limerick Chronicle, Bassett’s Daily Chronicle, The Times), a school certificate (“Latin Verse Composition”) and a few handwritten letters – is the confirmation it provides of the provenance of its companion volumes.

The recipes and remedies in this multigenerational collection were tried, tested, judged, adjusted and recommended by the Underwood, Maunsell and Caswell families over more than a century, giving us a valuable series of insights into the tastes, preoccupations and practices of these Irish households, and the wider social circles in which they moved.

SOLD Ref: 8097

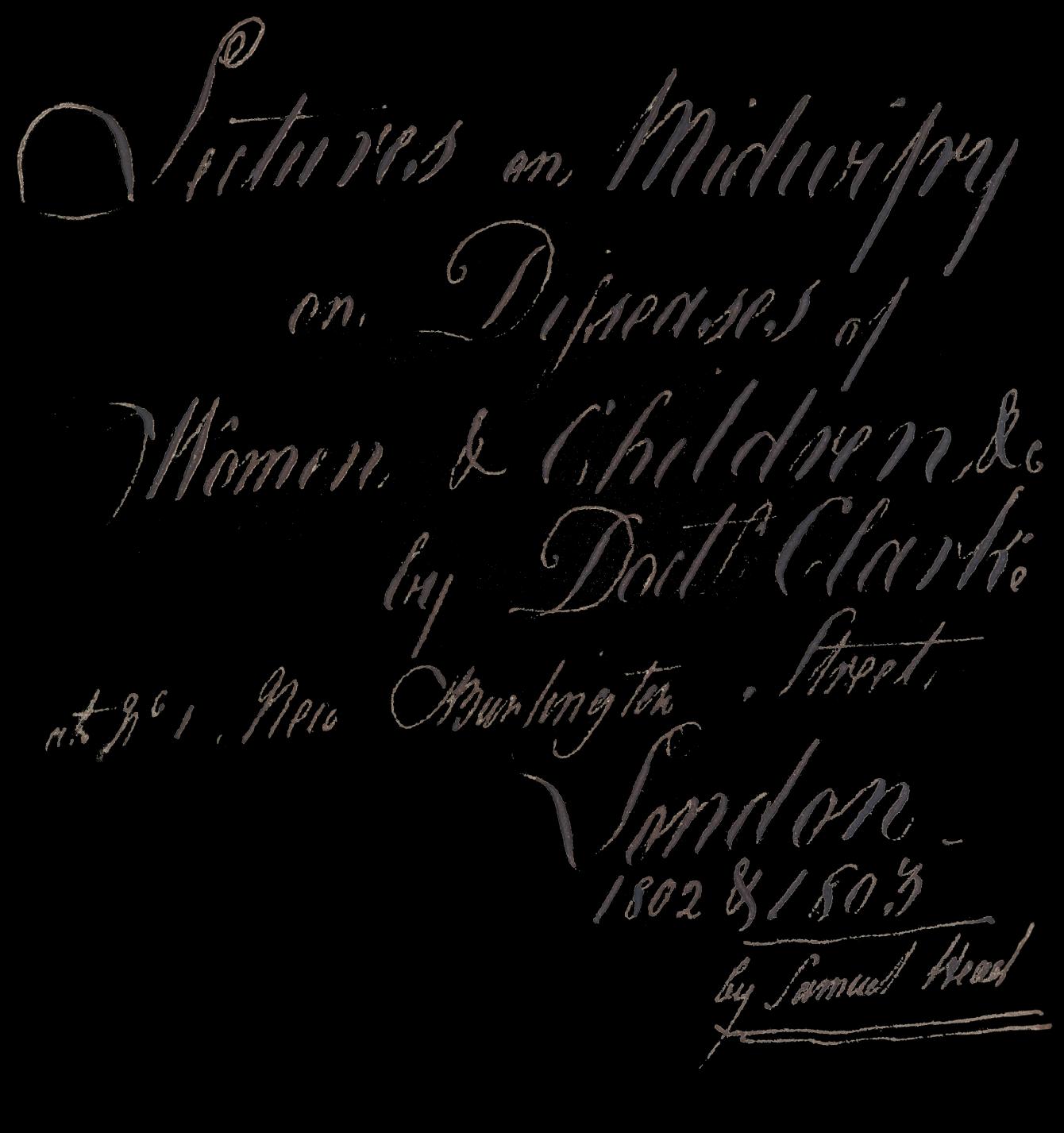

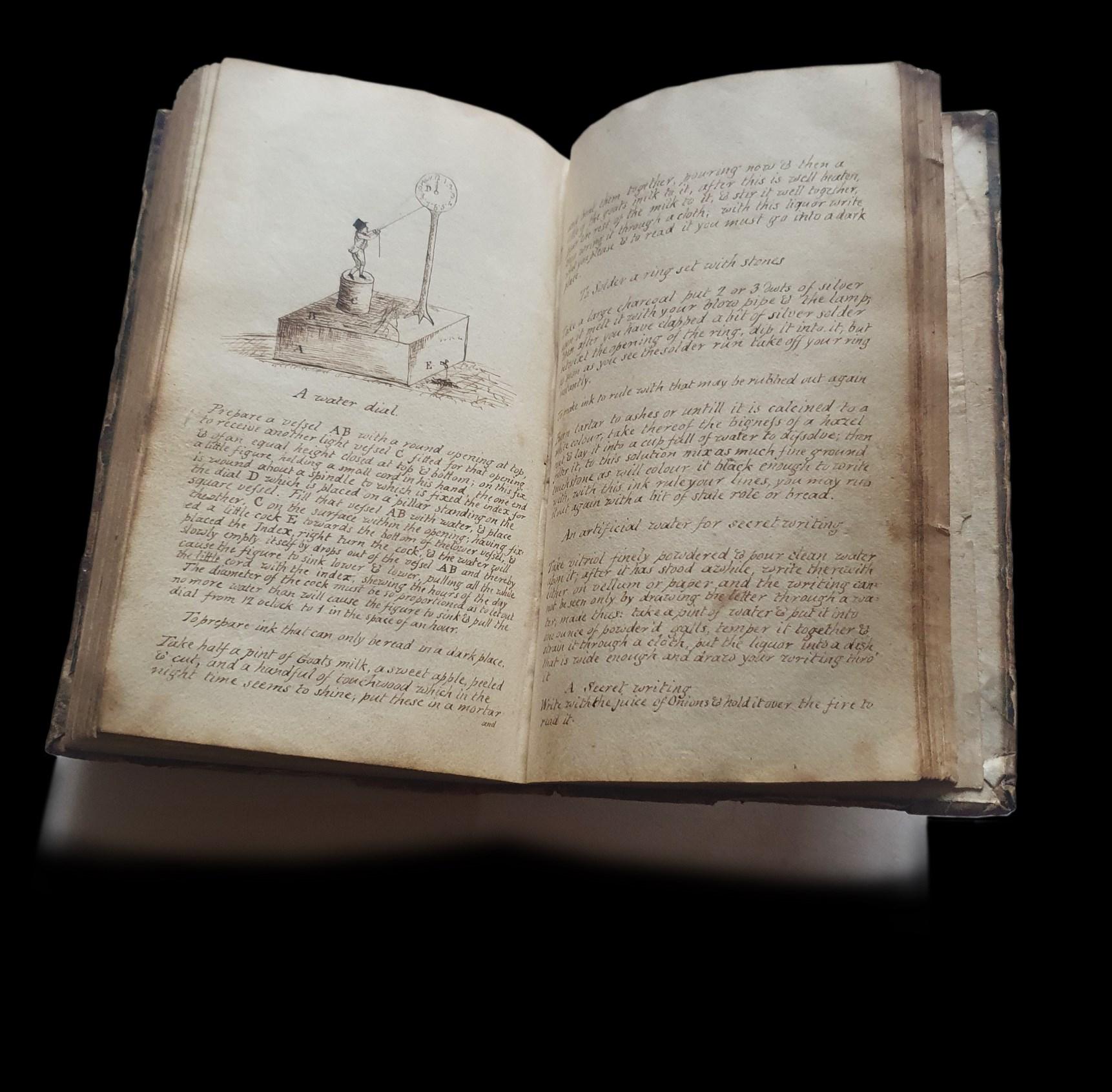

4. DRUG DISPENCER

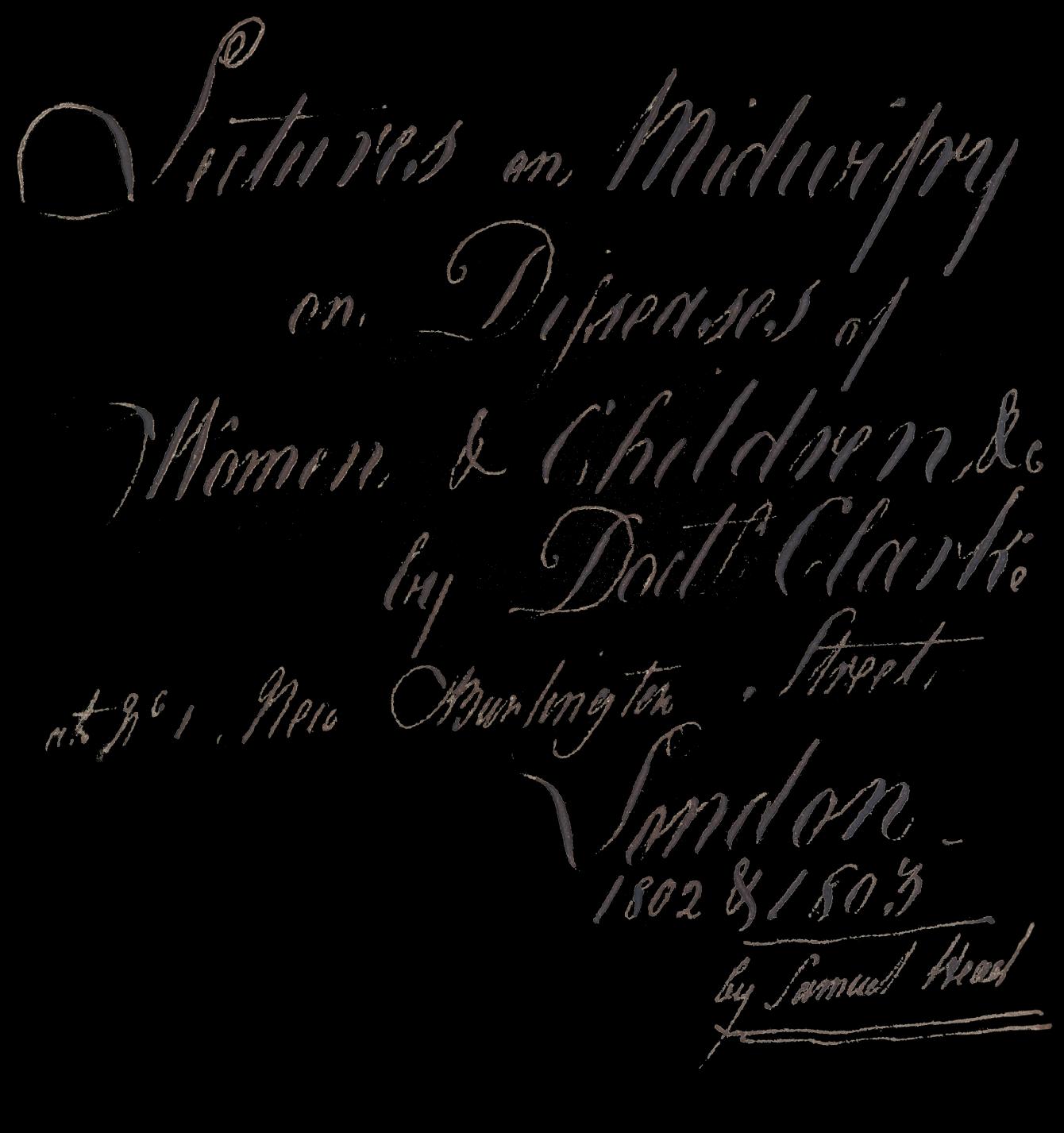

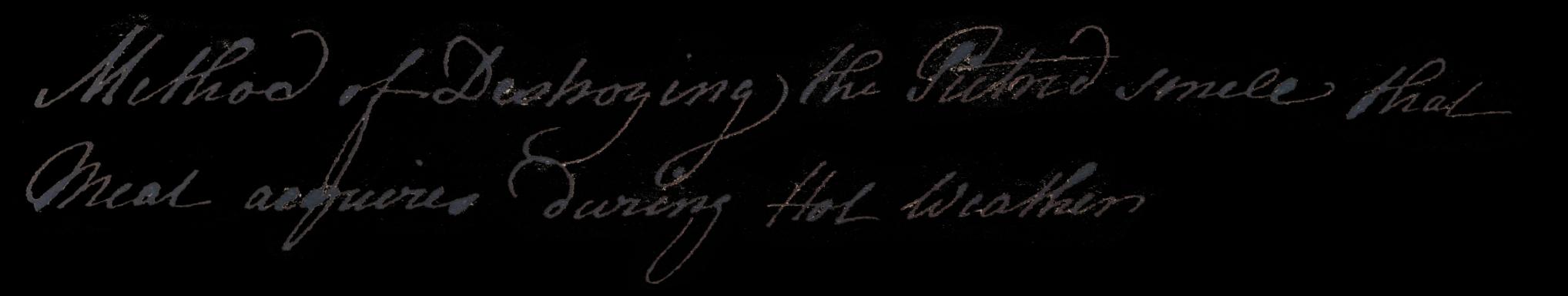

[SPENCER, Jonathan (1785-?)] Early 19th-century manuscript pharmacopoeia by a practicing medic.

[Salford? c.1810]. Quarto (202 x 165 x 3 mm), Approximately 30 text pages on 18 leaves, with two loose leaf remedies (one pinned). Stitched without covers. Numerous leaves excised at the end with only stubs remaining, first few leaves detaching, spotting and some staining. Four metal pins through first leaf attaching printed receipt for W. Bowman, chemist and druggist of Bury, and another copy of this receipt loosely inserted, both with manuscript recipe to verso. Watermark: P Tregent 1810.

¶ This heavily used pharmacopoeia was, according to the family from whom it originated, compiled by one Jonathan Spencer (b. 1785), of Salford, Manchester, where he practiced as a dentist, pharmacist and physician.

The text comprises 130 brief recipes for poultices (“Cataplasma Dauci Salive”, “Cataplas Sinapleas”), elixirs (“Elix Salutis Vulgo Daffys Elix”, “Tinct Benzoes Comp”), tinctures (“Tinct Aloes”, “Tinct Nicotianæ”), syrups (“Syrup of the Juce of Maberries”, “Syrup Zingiberis”) and other concoctions made and sold by apothecaries including “Cerat Saponis”, “Drops for Gravel of Stone”, and a few for treating

“Give one Twice a week untill the horse stales freeley”). Ingredients are mostly in Latin, with a few in English. Where instructions are included, these are usually provided in English (for “Elixir Asthmaticum”, the reader is advised that the “dose is from 20 to 100 drops to adults and 5 to 20 for children … in Hysop water or Canary”), as are many of the preparations (“Digest the Guaiacum & Balsam in the Spirit for six days & shake it after and strain it”). This is especially true of the section containing syrups, most of which feature details for preparation: for example, when making “Syrup Altea”, you should “Boil the root to one half and press out the Liquor and then add the sugar and Boil”, or for “Syrup , the advice is to “Macerate the root in the Vingar for Two Days now and then shaking the Vessel After strain it with a Gentle pressure To the strained Liquor add the sugar and . Many leaves appear to have been cut from the end, but it is uncertain whether these were blanks. What can be stated with some confidence, however, is that Spencer was actively using this manuscript in his everyday medical practice.

SOLD Ref: 8101

5. BEASTLY TREATMENTS

DOWNING, J. A treatise on the disorders incident to horned cattle, comprising a description of their symptoms, and the most rational methods of cure, founded on long experience. By J. Downing. To which are added, receipts for curing the gripes, staggers, and worms in horses; and an appendix, containing instructions for the extracting of calves.

[Stourbridge]: Printed and sold at Stourbridge. Sold also by T. Hurst, Messrs. Longman and Rees, Paternoster-Row; and Messrs. Rivington, St. Paul’s Church-Yard, London, 1797. Reissue of the first edition, published the same year. Octavo. Pagination xii, 131, [1], xiv (misnumbered ziv), [4] p. Lacking the half-title. Numerous blanks bound in at the end, with manuscript remedies to 14 pages. Modern half calf, marbled boards, endpapers renewed, some marks and browning to text.

¶ Downing’s treatise contains details of symptoms and treatments for diseases in cattle, together with a small number of remedies for maladies in horses. Of its over listed 250 subscribers, a many are local to Stourbridge or Worcestershire generally, from where the author hailed. Many were presumably landowners, yeomen or people otherwise directly concerned with farming, but the list also includes professions such as surgeon and druggist, and of course booksellers.

Whichever of these groups our scribe belongs to, they have augmented the work into the 19 adding some 31 recipes and remedies (variously from 1803 to 1840) including “For Black Water in Cattle”, To Prevent Calves Striking”, “For a Gargett in a Cows Elder”, “To take A kell of a Horses Eye”, “Diuretic for inflam’d Legs, on a Horse”, and “To prevent Sheep from striking”. Most simply list ingredients and quantities, but there are short notes (“the eye to be rub’d twice pr Day”), and some more detailed instructions like: “The Beast should be bled freely and milked quite clean. [...] If it should so happen to be milked more than once [...] it destroys the effect of the medicine [...] though the Udder appears full, yet it should gradually diminish without any injury to the beast.”

all the practical remedies for animals,

they’ve allowed themselves some indulgence, judging by a recipe “To make Punch Ice” (not for the livestock, one imagines) using oranges, lemons, brandy and rum. Some remedies are ascribed to the likes of “Casewell”, “Humphreys”, “R. A. Charleton”, “Geo: Hampton” and £750 Ref: 8098

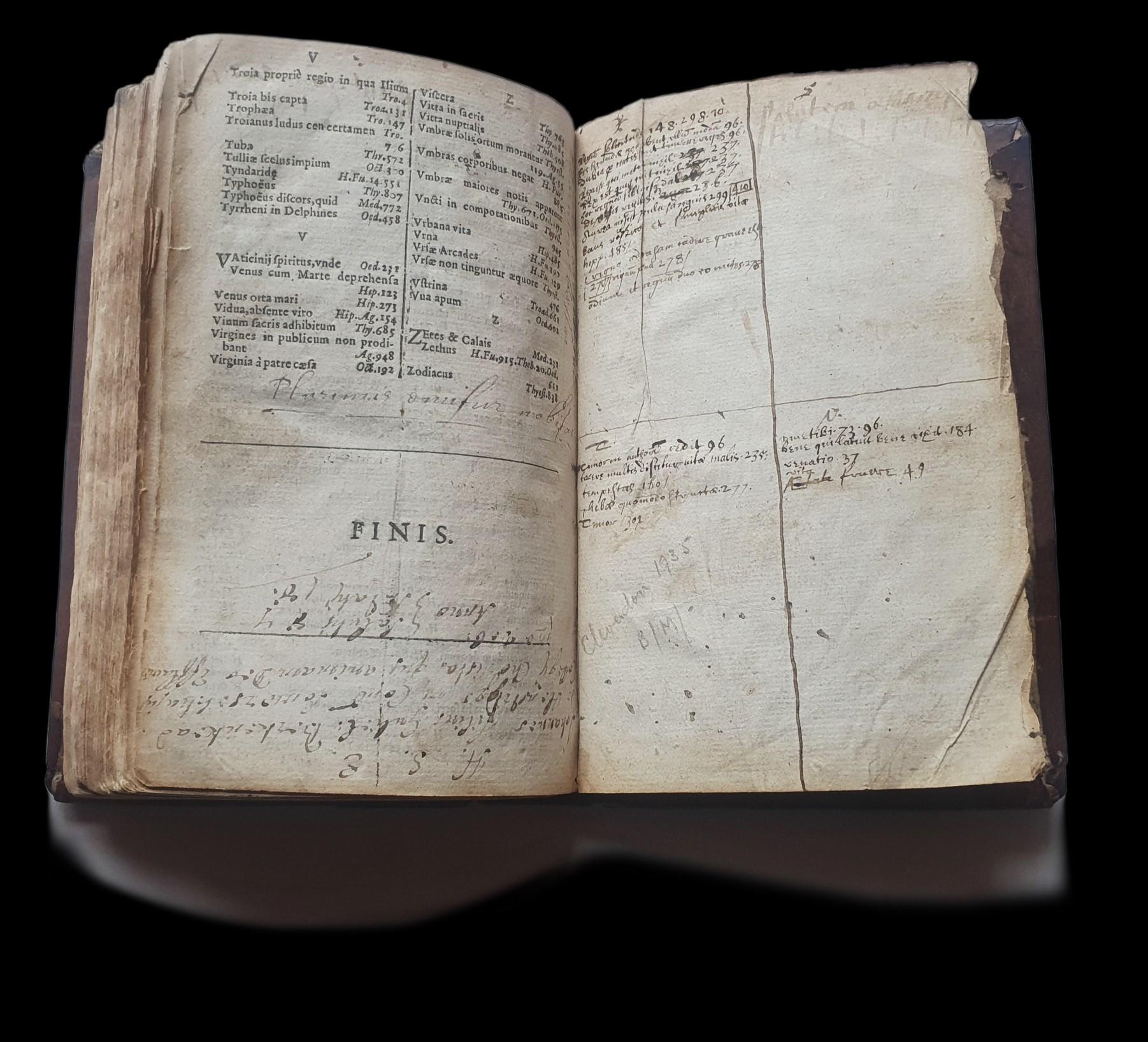

6. MAKING ENGLISH SIMPLES

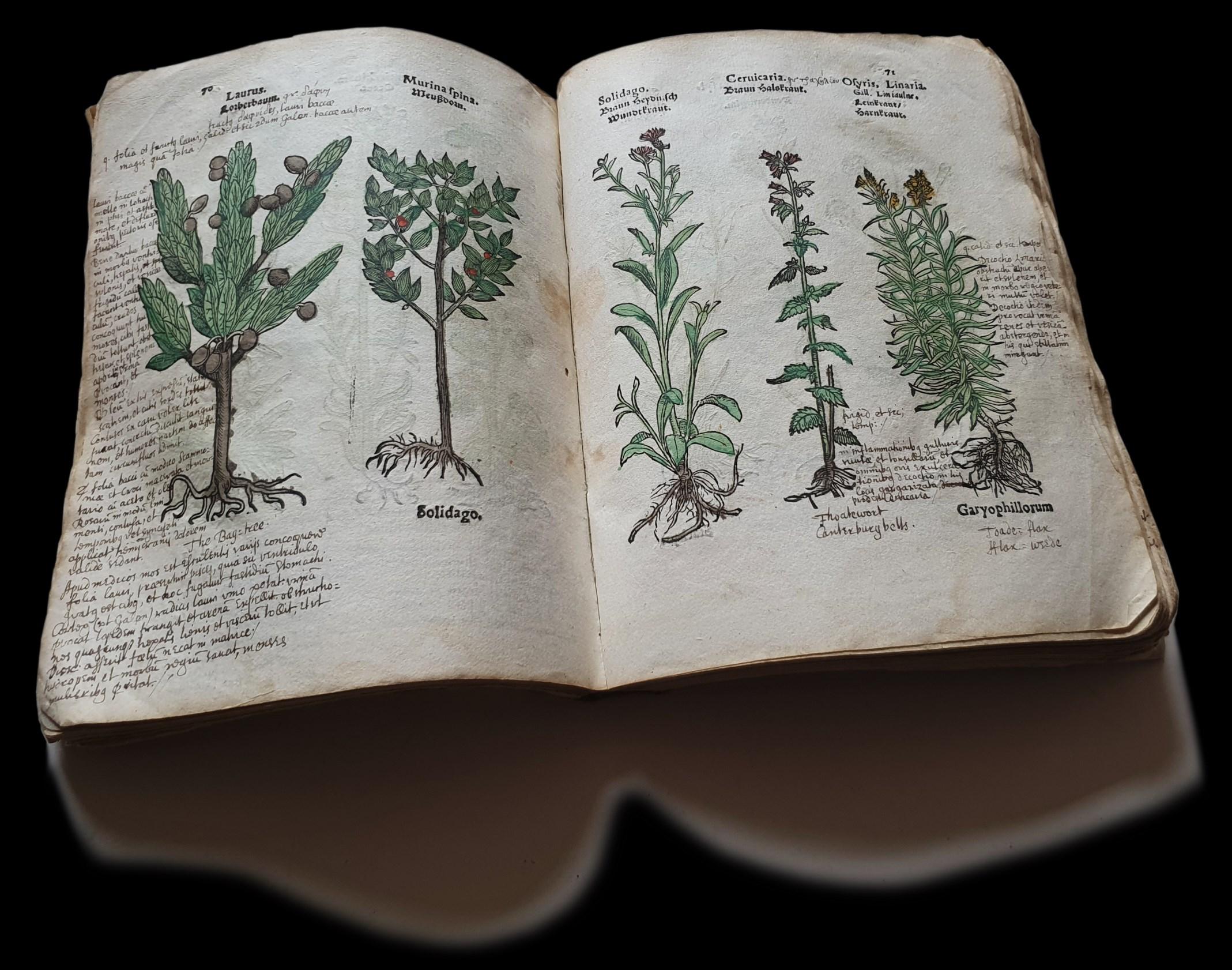

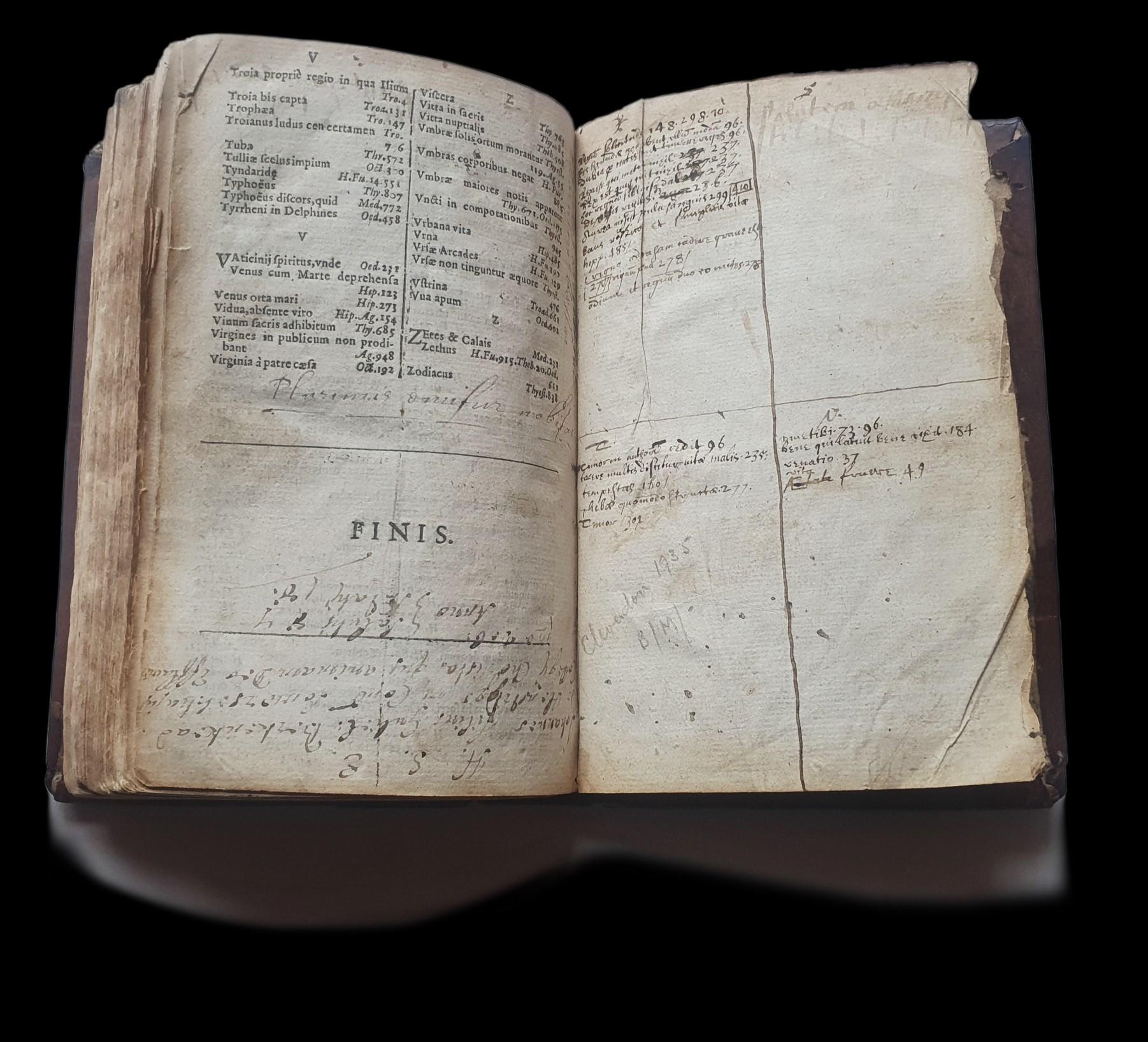

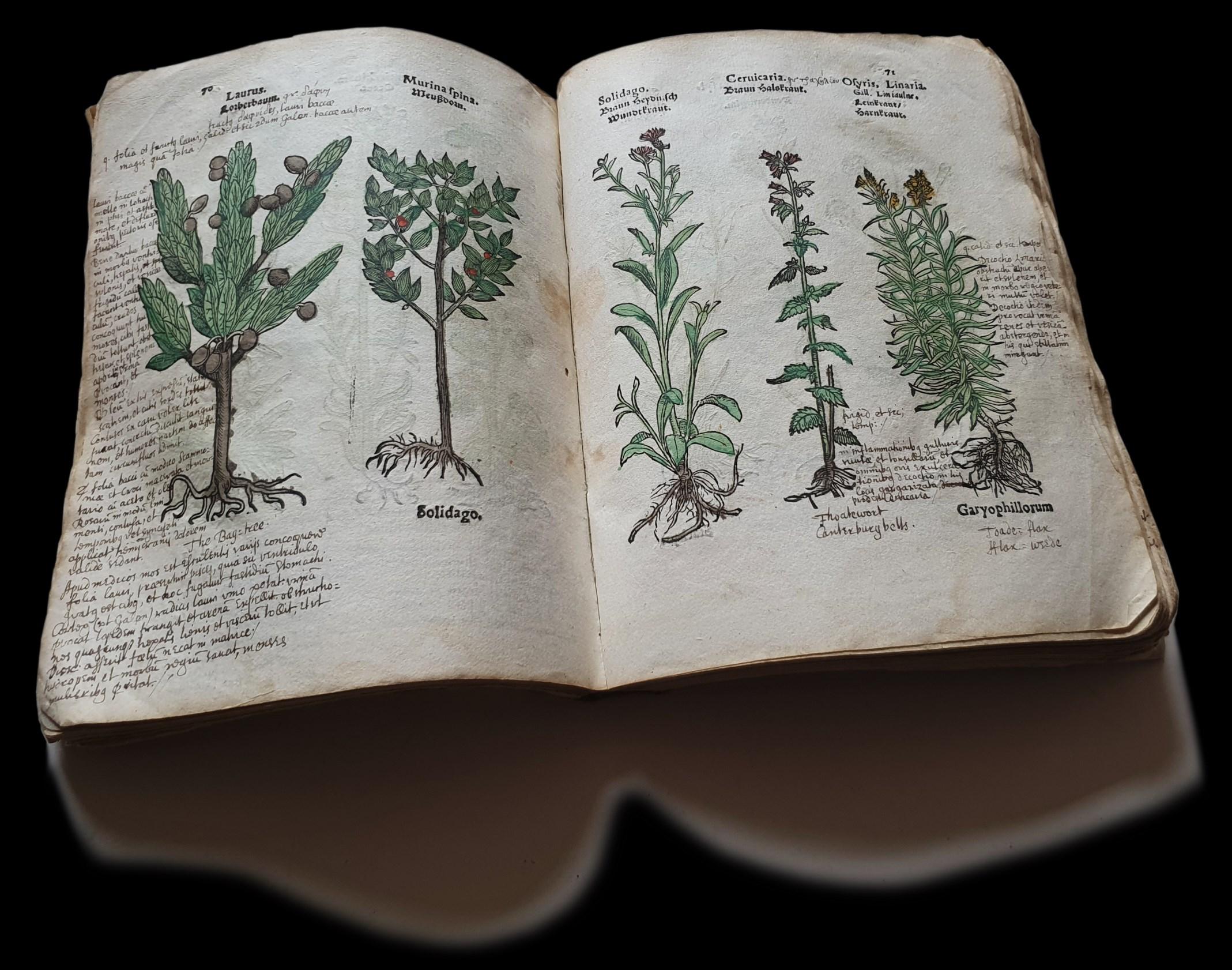

EGENOLFF, Christian Herbarum, arborum, fruticum, frumentorum ac leguminum, animalium præterea terrestrium, uolatiliu[m] & aquatilium, aliorumqq´[ue] quorum in medicinis usus est, simplicium, imagines

Apud Chr. Egenolphum, Franc, [M.D. LII]

Quarto. [4 (of 16, i.e. lacking title and most of index], 294 (of 312 of which 10 are lacking and 8 have been replaced in high quality facsimile, with competent hand-colouring). Woodcut illustrations with contemporary hand-colouring throughout. Copiously annotated throughout in a 17th-century hand. Bound in contemporary limp vellum, recent silk ties and manuscript title to front board (incorrectly dated in a modern hand). The book has clearly been heavily used and been the subject of modern restoration.

¶ “Renaissance herbalists composed their texts primarily by “gathering,” synthesizing, and commenting upon the materials of their predecessors and using this information as a scaffold upon which they could then record their own differing or dissenti experience.”1

This book’s annotator has largely followed the method that Sarah Neville describes above: having absorbed a range of sources – from classical authors to their own experience and contemporary practice – they have melded the material to create a kind of hybrid. The result is a personalised (and evidently well used) reference tool for a member of the 17th-century medical profession, most likely a ‘field guide’ as well as a medicinal resource.

The Herbarum, Arborum, Fructicum was first published in 1545 by the Frankfurt printer Christian Egenolff (1502-1555), considered the first important printer and publisher operating from Frankfurt-am-Main, and best known for his publications of herbals and re-issue of books by Adam Ries, Erasmus von Rotterdam and Ulrich von Hutten. However, he is also remembered for his protracted squabble with the botanist Leonhart Fuchs (1501-1566) over violation of copyright and was sued by the Strasbourg printer Johannes Schott (1477-c.1550). Egenolff successfully defended himself by claiming that “images of the natural world such as plants could not be protected as works of art” because “the ultimate artist responsible for [their] image is God”2 .

ENGLISH DOCTOR OR APOTHECARY?

But who is our scribe? Clues to their identity are scarce, but the ease with which they move from English to Latin and occasionally Ancient Greek indicates that they were English and highly educated, and we can be reasonably confident that they were a practicing physician –either a doctor or an apothecary, judging by the fact that the annotations focus on the plants’ medicinal uses. The English herbalist William Turner (c.1509-1568) contends that there were few “surgianes and apothecaries […] in England, which can understande Plini in Latin or Galene and Dioscorides […] in Greke or translated into Latin”.3 Our scribe cites these authors and is evidently Greek and Latin literate; underscoring the blurred boundaries that still existed between these nascent professions.

It was, however, still clearly important to our medic to annotate almost every plant with its common English name. But, having checked many of the English 16th- and 17th-century herbals, we find that few of the names have a close match. There is no suggestion of an attempt to systematise along the lines of Nehemiah Grew (1641-1712) or John Ray (1627-1705), so a simpler, more practical explanation seems the most likely: this being a bespoke reference guide for practical use, the added names appear to be those used in common parlance and were probably recorded to aid communication with non-Latin speakers.

The choice of a German herbal as the groundwork for this project is an interesting one. Our 17th-century medic would have had a number of English herbals to choose from, including William Turner’s (d.1568) New Herbal (1551) John Gerard’s (15451612) Herball (1597 and the 1633, revised by Johnson), and Henry Lyte’s (1529?-1607) Herball. These were handsomely illustrated volumes with explanatory text, but of prodigious size, weighing several kilograms and needing a table in order to be read. What would have made this book so appealing to our medic, are its small size and the lifelike illustrations, making it the only medicinal plant identification handbook that could be carried in a pocket while walking in the countryside. There were

illustrated pocket editions of Leonard Fuchs’ Historia Stirpium (1551) with tiny woodcuts and full Latin text, but Egenolff’s little reference book was a clear winner for its usefulness and convenience. This ‘adapted’ copy is all the rarer in view of the low survival rate of such handbooks.

ROOTS AND BRANCHES

We can speculate about some of our scribe’s sources with more confidence: classical authors are namechecked many times, for example Dioscorides, whose method of abortion is cited in the notes on “Laurus” (“Diosc: asserit foetū necat in matrice”

which translates as “Dioscorides asserts, it kills the foetus in the womb” The work of Galen is strongly represented, usually in Latin ( Galen” p.70 and elsewhere) and occasionally in English ( Poore mans Treacle” p.81).

More specific book references seem to be rare (as far as we can determine), but a notable exception occurs with ‘Acer’ on p.37 where the scribe writes Maple tree”, and cites “Pliny 24 lib: cap. 8.” who conclusu et applicat dolorem hepatis egregie fugare” the maple tree and applies it to drive away the pain of the liver very well”). This reinforces the impression that, by the time of the manuscript’s composition, our medic has long since absorbed, internalised, and blended knowledge from printed sources and perhaps first general outlook and skillset. The virtually text-free nature of Egenolff’s printed book therefore enables them to fill the clear leaves with all that they know about the subject – and they clearly know a great deal commentaries of other authors.

HERBS AND HUMOURS

The volume abounds with handwritten instructions and memos concerning medicinal uses of the specimen concerned. The plantain, for example, is commended as a remedy for both dysentery and earache (“auriū dolores”), for the latter ailment prescribing drops in the ear (“auritus instillata”) and, in cases of emergency ( (“injecta syringae”). The scribe also observes (in English) the potentiating advantages of mixing: “Borage and buglosse may be reduc’d both to the same kind off herbes althoughe they have severall denominations in Eff: Phys: put the leaues floures and rootes in the same medimies because by connexinge off them togeather, and because they p[ro]duce the same effects, et vis unita forlior. Una potest esse alte rious succedaner” (“and a united force. One can be highly successful”) (p.9).

–

Some plants mentioned have retained their place of prominence in modern herbal medicine, although not always for the qualities we’ve become accustomed to: “Hypericum”, or St John’s wort, “cum flore et semine, coctum et potatum urinam deducit et in vesica lapidem diminuit” (“with flowers and seed, cooked and drunk, produces urine, and reduces the stone in the bladder”), and its leaves “macerata aqua ambustis, vulneribus et ulceribus saniosis prosunt” (“soaked in water are beneficial for burns, wounds and suppurating ulcers”).

It comes as no surprise in a work of this period that great emphasis is placed on the balancing of humours: beside “Buglossum” (p.9) is the note: “fuligimosos melancholiae hality reprimunt haec duo” (“these two repress the black melancholy”); and while comparing the digestive efficacy of varieties of “Nardum” (p.42), our medic comments: “Nardum Indicum, vel verus nardus, calefacientem et siccantem habet qualitatem, secundum Galen califaciens primum et siccans

humours circulating around the affected part”) – to say nothing of its benefits in aiding digestion and treating a headache.

The book has undergone more recent repair and preservation work, which complicates its material history by adding a layer of modification. But it nevertheless offers visually beguiling, first-hand evidence of the level of expertise of an English 17thcentury medic and a working demonstration of Neville’s assertion that “later herbals descended from earlier ones, and previously printed botanical books were a crucial location for herbalists’ “gathering” behaviours”5. We have concentrated on only a few pages of annotations; there is much more to digest here for the scholar of 17th-century medicine, and plenty to explore in detail.

1. Sarah Neville. Early Modern Herbals and the Book Trade, p.70

2. Ibid, p. 57

3. www.rcpe.ac.uk/heritage/william-turner-and-first-english-herbal

SOLD Ref: 8095

4. This and the following translations are approximate and sometimes reliant on unclear Latin. We are indebted to Christopher Whittick for his help in interpreting the text.

5. Sarah Neville. Early Modern Herbals and the Book Trade, p. 217.

7. LOCAL KNOWLEDGE

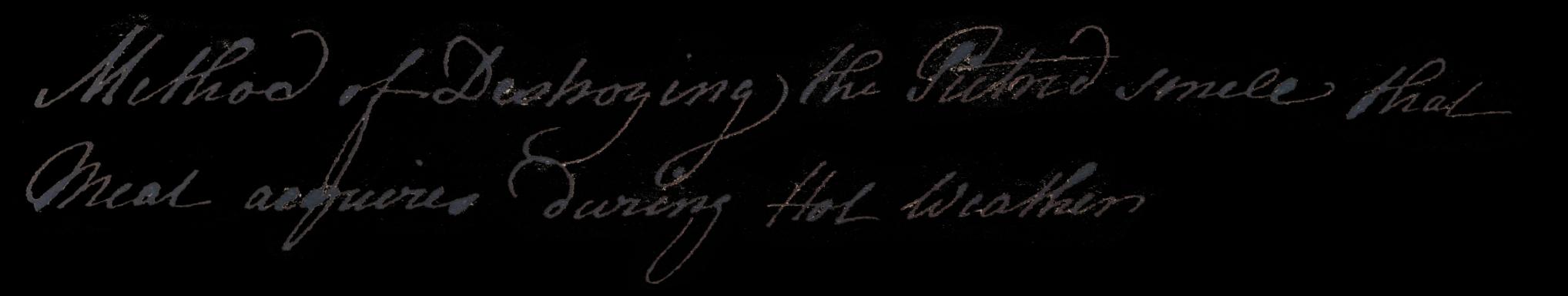

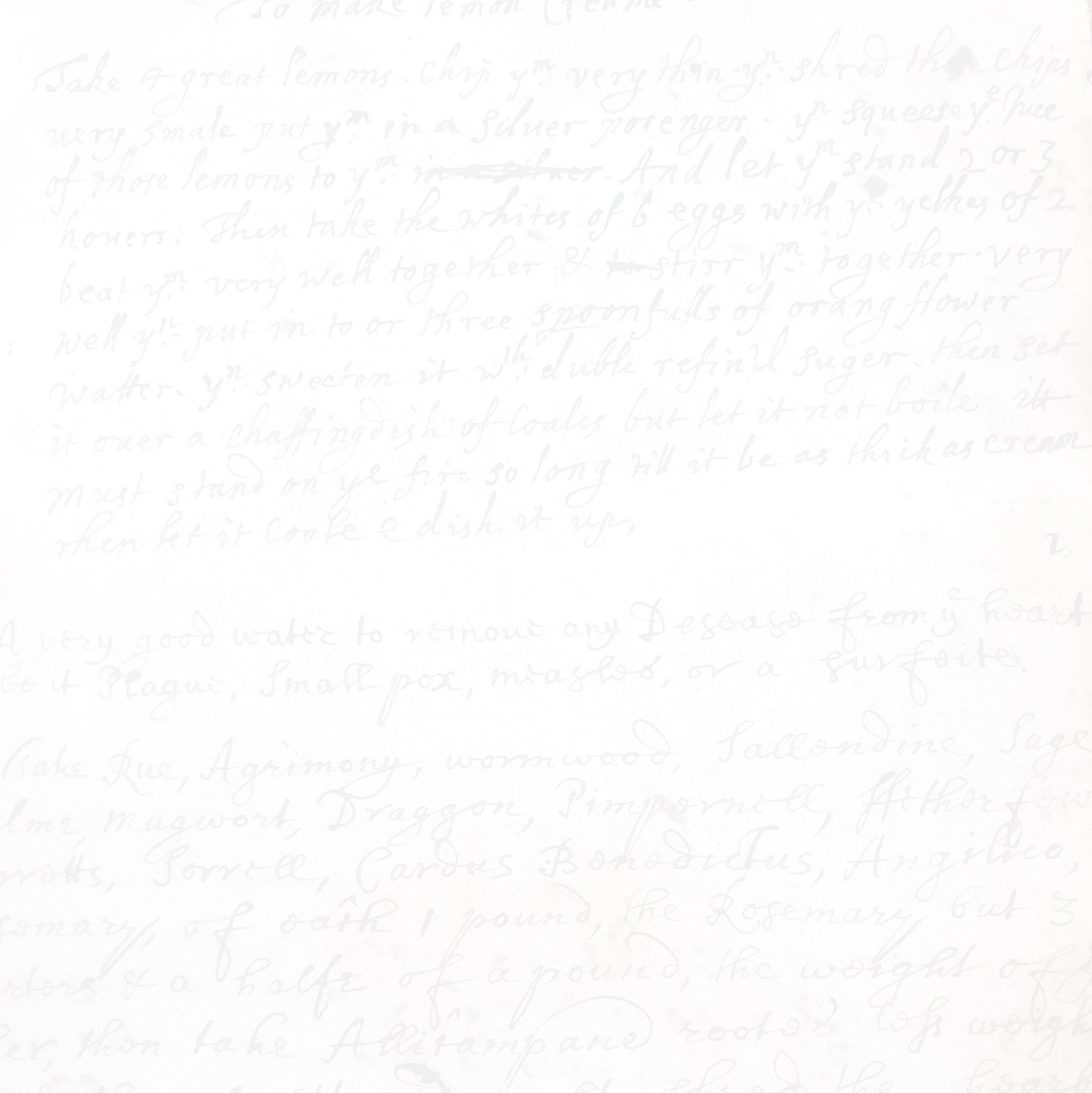

[GIBERNE] Manuscript book of recipes and remedies.

[Circa 1775-1830]. Quarto (210 x 168 x 19 mm). Pagination [13, index], [2, blanks], 157 numbered pages (pages 38/39 torn out). Contemporary vellum, torn at head of spine. Manuscript title to front board “Receipt Book of Medicines”, but also contains numerous culinary recipes. Pencil inscription to front paste-down reads “Giberne”

¶ This comprehensive collection of remedies, while apparently compiled for household use, perhaps served a wider reach; its many attributions and named endorsements certainly indicate a healthy social network. There are well over 350 remedies, compiled at different times, by at least two scribes, suggesting either that the household was unusually large and frequently unwell or that the Giberne family’s expertise was much drawn upon by the local community. The remedies are often quite brief and suggest a familiarity with the language of the apothecary.

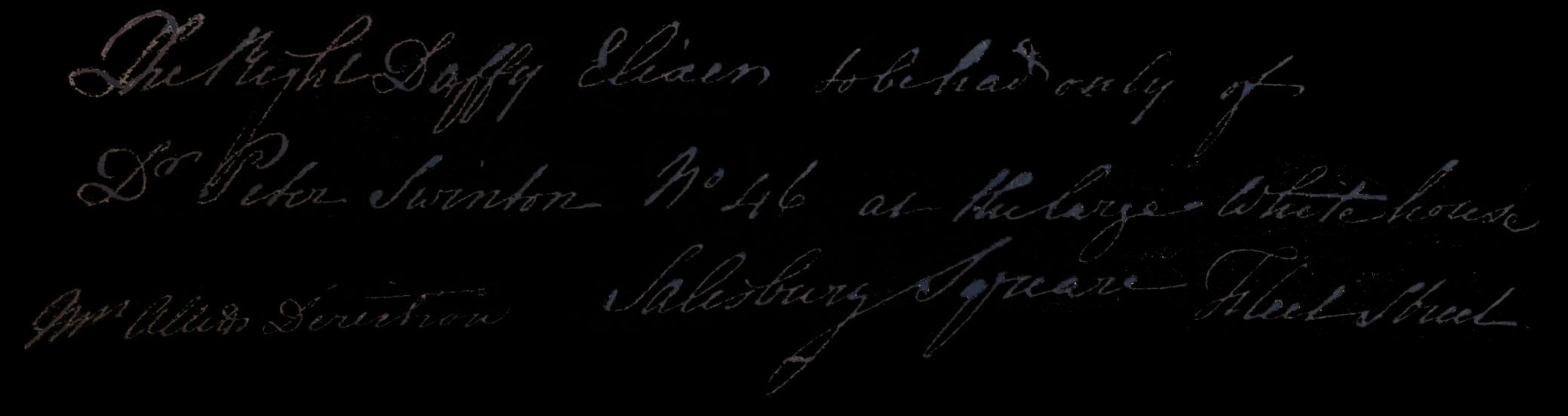

Remedies are often clustered according to the ailment, and augmented over time, while others are simply inserted randomly into gaps. Time and again, the Gibernes demonstrate – or, at least, claim – their privileged knowledge by adding qualifications and recommendations to these remedies. Their presentation of the ever-popular Daffy’s Elixir, for example, carries the specific caveat: “The Right Daffy Elixir to be had only of Dr Peter Swinton No 46 at the large White House Salisbury Square Fleet Street – Mrs Allens(?) Direction”; and the ubiquitous cure for a run-in with a wandering mutt (“To Cure the Bite of a Mad Dog”), here copied from the “Hampshire Chronicle March 10th 1777”, is annotated “Dr Haygarth of Chester, suggests that to wash the Wound as soon as possible wh Water for an hour during wh time should be frequently squeezed”. Similarly, their cure for “Rheumatism” recommends “Husks of Mustard” which should “only be bought at the Mustard Manufactory City Road London”, but carries the encomium: “C. Berry our Servant always found beneficial”.

Most of the remedies are attributed: some acknowledge their printed sources (“See Mrs Glasse’s Book” (p.142)), others their manuscript sources (“Remedy against the Plague” on p.123, is copied from “Mrs Dryden’s Old Rect Book”). A great number suggest a more personal connection: for corns, “Mary our Cook from Wales” (p.155) recommends “Soft Soap, & brown sugar, made like a paste” and on p.15 “Mrs Giberne” has something for “Head Ach”, alongside two other remedies for the same condition; one from a “Mrs Freeman”, the other from “Wilkinson”. Another member of the family (“Mr Mark Giberne”) has a simple recipe “For the Hands” (p.120), and a “Mrs Crispen of Clifton Septr 1777” has “A Good Receipt for Cleaning the Teeth [...] NB: a fourth part of the above quantity may be sufficient to get made at a time. It may be used upon the Teeth either with a soft Brush, or soft Linnen” (p.149). Meanwhile, “Mr Powell / Hair Dresser at Worcester” (p.156) has something “To Thicken Hair”.

Names and measures typical of an apothecary are much in evidence: a remedy to alleviate “Shortness of Breath” comes with specific instructions: “Miss Benson 1803. She takes two pills at Night When her Breath is Affected most, Ann takes but one” (p.71); and “An Electuary made for me, by Mr: Crew 1769” (p.14) includes directions that it should be taken in “The quantity of a Large Nutmeg at Night or Early in the Morning”; while another is attributed to “A Prescription of Dr Fothergales for Miss Dewbery” (p.145). Among the entries are occasional memoranda that contribute to the sense that this manuscript served as a more general resource of services: for example, “Academy for the Deaf and Dumb. Mt Braidwood, Junr in Mare Street Hackney} cures Gentlemen. Mrs Braidwood cures and instructs Ladies”, which is updated in (aptly) darker ink “Mr B Since Dead” (p.104).

Some remedies feature instructions in varying degrees of detail that suggest an exacting approach to their use: “Great care must be taken to prepare the Aloes properly”, warns one, “with juice of Violets or a very strong tincture of Liquorice [...] One or two Pills is a Dose immediately before Dinner or Supper” (p.37); others suggest options for improvement: “Milk Punch” is annotated “When you put it in the Barel you may add 3 pints of warm milk from the Cow, or Omit it, just as you please” (p.136), and the efficacy of “A Good Gargle for a Sore Throat” (which includes “Honeysuckle, Bramble & Sage Leaves [and] port wine”) is not spoiled simply because it has festered, for “If it is Mouldy in the Bottle by keeping it is not the worse when skim’d off” (p.120).

These refinements confirm that the compilers are trying, testing, and either improving or completely rejecting some remedies. For example, among a group of 18th-century remedies for scurvy (one is dated 1779 and another 1780) is a cure for “Stone Gravel”, which, although added later (Bath Herald in 1813), seems less satisfactory than the earlier cures, since it carries the remark “I do not reccommd the tryal” (p.144). Another remedy, this time “For reducing corpulency”, (p.143) is curtly dismissed with “I would not reccomd this”, and “A certain and speedy Remedy for pimples that rise or settle in the face &c.” from the Gentleman’s Magazine (1752) is annotated “I do not reccommd the tryal” (p.144). No such qualms are expressed, however, over the directions “To Stop Bleeding at the Nose”, despite seeming more likely to terrify than to cure the sufferer: “Hold the Head over a Red Hot, Heater, or Iron”.

the cutting and preparing of the fish, which, following the addition of ingredients such as “strong Beer Allagar, half an ounce of Mace, the same of Cloves, [...] one ounce of long pepper, 2 ounces of white Ginger”, will “Keep a Year round” (p.138). “Beer drank at Sydney College in 1801” is provided by “Revd Geoe Butler – of Sydney College Cambridge 1801” (p.101).

This is a particularly noteworthy collection of remedies, thanks to the presence of so many attributions and named individuals. Whether or not the Gibernes had the reputation as apothecaries that some aspects of the manuscript might imply, the sheer profusion of contacts and sources mentioned here makes this an object that reaches out in many directions from its household origins.

SOLD Ref: 7966

8. LOCKED UP

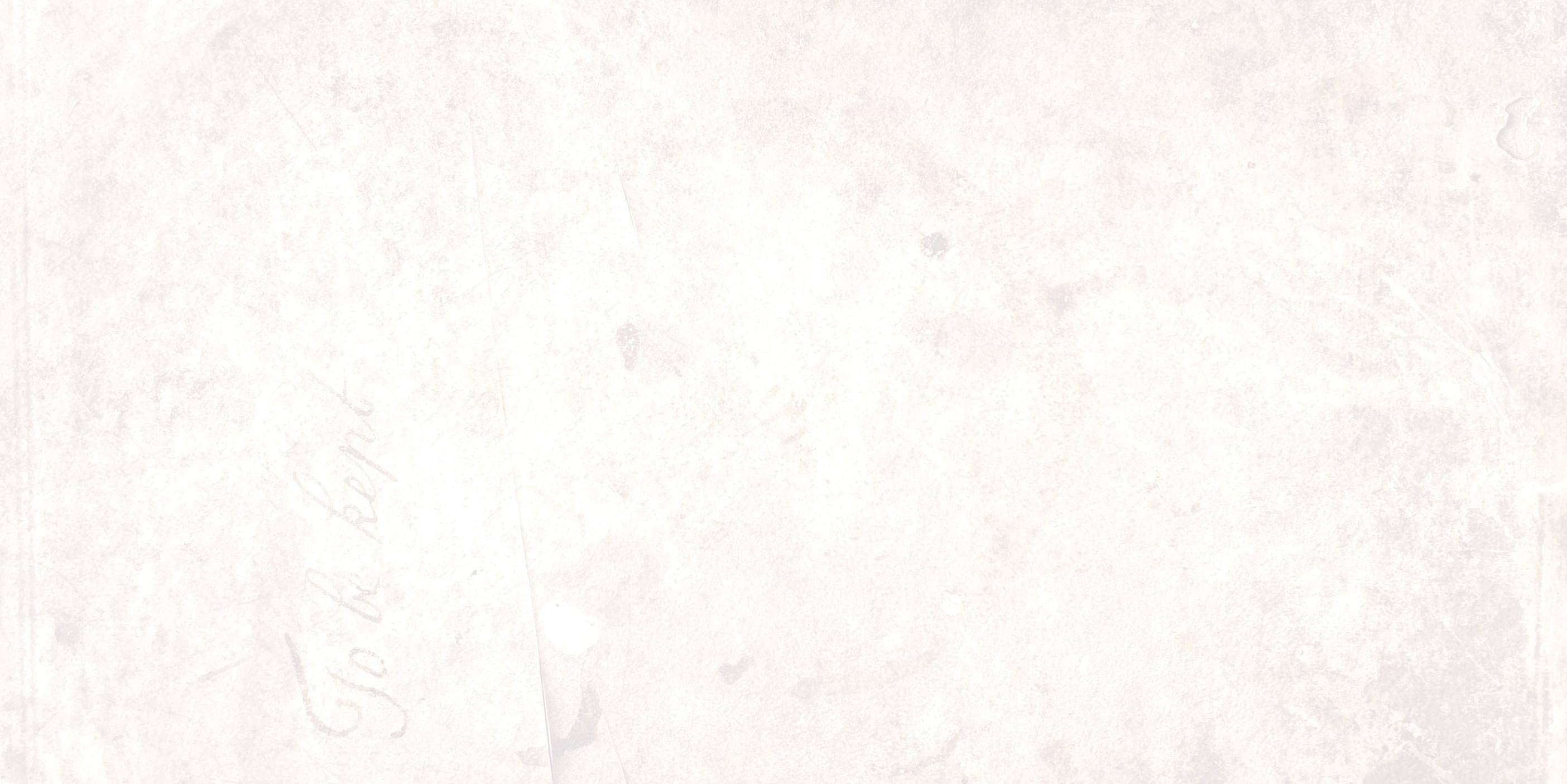

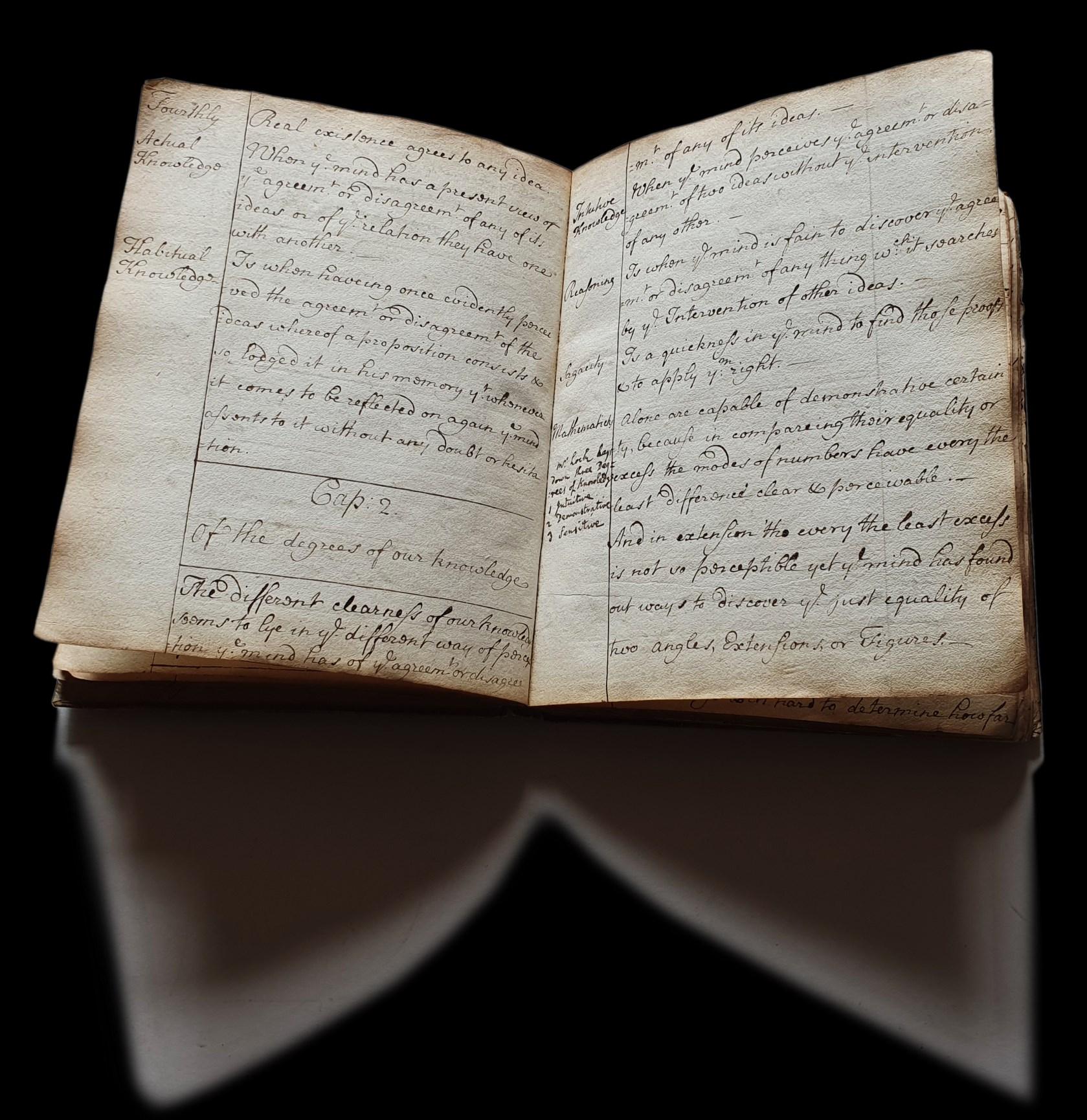

CALLAGHAN, Robert (1708-1761). 18th-century lawyer’s manuscript legal and philosophical notebook.

Quarto (205 x 160 x 30 mm). Dos-a-dos: 145 pages of legal and philosophical notes at one end; 102 pages of notes contracting Locke at opposite end. 247 text pages on 128 leaves.

Bound in contemporary full vellum, probably a stationer’s binding, tear to spine and long slash across one board, manuscript note to opposite board reads “To be kept”

Watermark: Coat of Arms above initials “RD” (similar to Haewood 417, circa 1739, but he does not record any initials).

INTRODUCTION

¶ The process of abridging texts is central to the practice of law. In précising, the student absorbs and fixes ideas, making them more able to mobilise these when needed. As Francis Bacon observed “Reading maketh a full man; conference a ready man; and writing an exact man.” Here we see our newly qualified lawyer practising their art on classical and contemporary philosophical and legal texts. Chief among them is the philosophy of John Locke, whose ideas dismantled the “divine right of kings” and replaced it with the rational, self-determining individual freed from paternalist rule. The ruler derives authority not from God, but from the consent of the people whose interests they must serve, especially “life, liberty, and estate”. These ideas underpinned the United States Constitution.

WHO COMPILED THIS VOLUME?

The scribe identifies himself several times on the first text page and elsewhere as “Robt Callaghan”. This is probably Robert Callaghan (also O’Callaghan) (1708-1761), of Dublin. Support for this attribution comes from another inscription to the pastedown which reads “Thomas Callaghan ye youngest son of C C:” The initials “C C:” likely refer to Robert’s father, the eminent lawyer and member of parliament, Cornelius Callaghan (1682-1742); Thomas Callaghan (1713-1742), also a lawyer, was indeed Cornelius’ youngest son.

Robert attended Dr Thomas Sheridan’s preparatory school in Dublin and was an alumnus of Trinity College (BA 1729). He then studied at Middle Temple in London, before returning to Dublin where he entered King’s Inns in or about 1733, when this manuscript was written. As well as following his father into the law, he too became a member of parliament, representing Fethard, Tipperary in the Irish House of Commons between 1755 and 1760.

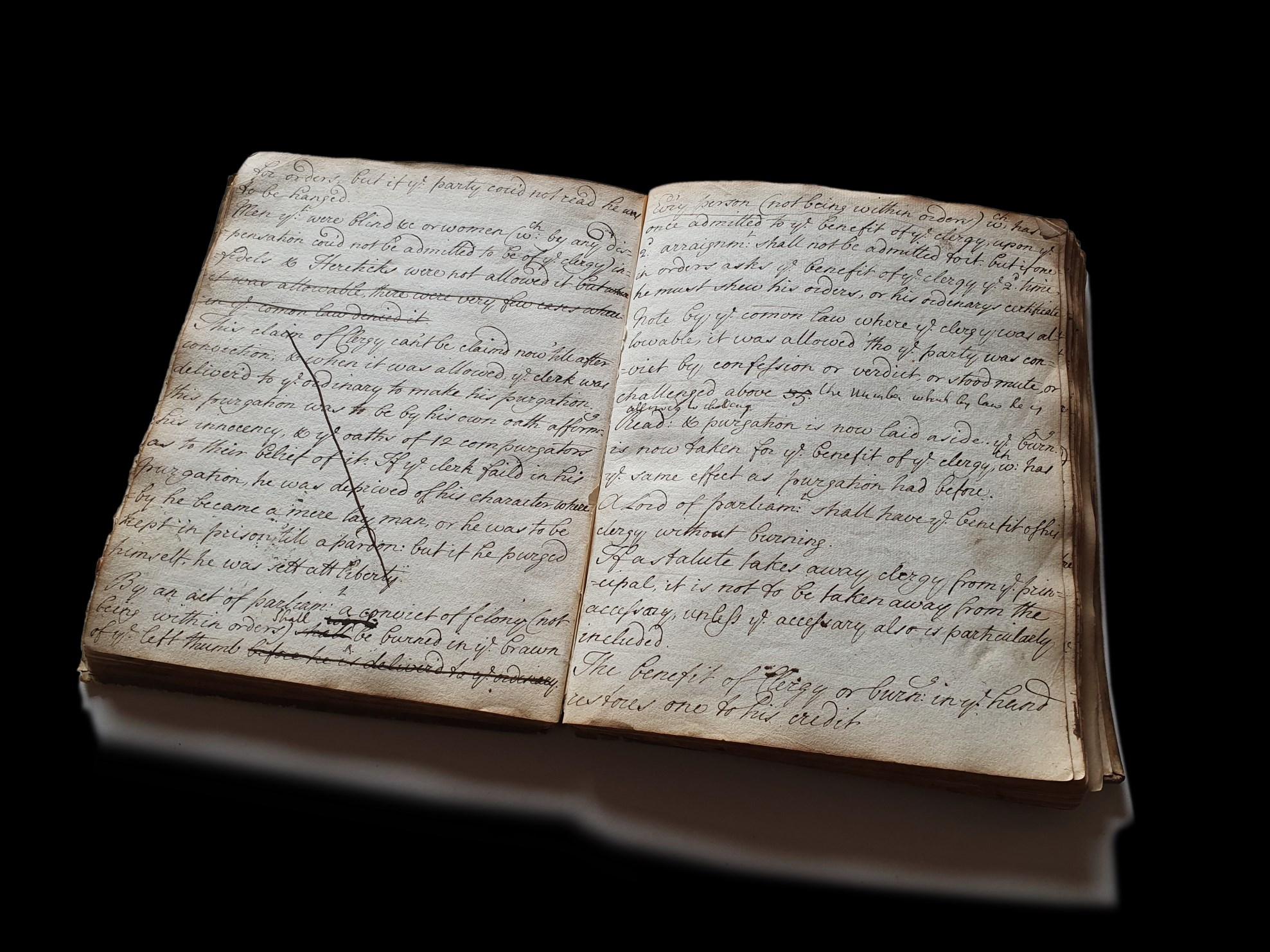

DEATH AND PROPERTY

In what appear to be the earliest entries in this manuscript (the date 1731 is written on the first leaf), Callaghan makes notes on “Rent Service as ye law now stands”. But on the following page he begins with summaries of the first three chapters of JeanBaptiste Du Hamel’s (1624-1706) Philosophia vetus et noua ad usum scholae accomodata (1682), which presents ideas from the experimental philosophy of the Academie Royale des Sciences (Du Hamel was its first secretary). He follows this with contractions of other works in Latin, apparently drawn from Democritus and Epicurus and also name-checking Plato and Aristotle. Callaghan devotes a total of 19 pages to these matters, before moving on to topics more directly related to his work as a lawyer.

The first grouping covers land law, possession, and eviction, and also takes in tenancy, chattels, “Fealty”, “Franckalmoigne”, “Homage auncestrell”, inheritance, and others in this vein. Other subjects included are the ever-useful “Court of the Powders” (the itinerant court for dealing with disputes on market days), the ubiquitous “Crimes & Misdemeanors”, and the more bluntly expressed “killing” and its prosecution.

Indeed, after property, death (whether at the hands of oneself or others) occupies much of his attention. He notes that “Capital offences are of three sorts, High Treason, Petit Treason, Felony”; that “Murder of one’s self may be comitted when one kills himself by hanging, Poysoning, Drowng, stabbing &c, with deliberation & a direct purpose. in this case one is termed felo de se”; and that “if an infant under 14 years old, or a Lunatick during his lunacy, or one distracted by force of a disease, or an Ideot, kills himself it is not felony”. (These and other passages probably come from Thomas Wood’s An Institute of the Laws of England (1720).) He then enlarges upon this theme, discussing “Manslaughter” (“ye killing of another w.out malice in a present

heat on a sudden quarrell, upon a just provocation, or in ye Comission of a voluntary & unlawfull act without any deliberate intention of doing mischief”) and “Chance medley”, then “excusable homicide” and “Justifiable homicide”.

As with the other sections in this volume, Callaghan does not copy out uncritically the thoughts of others. In the legal sections, as well as summarising laws and cases (“Ld Buckhursts Case” – short summary of the judgement; “Sr Willm Pelhams Case”; “Porters Case”; “Alton Woods Case” … “That wherever ye King is deceived in his grant it is void.”), he amends, corrects and adds to the texts. Appropriately for an Irish practitioner, he also makes occasional notes on laws in England compared to those in Ireland (“Arson (from ardeo to burn) is a felony att Com[m]on law, & is a malicious & voluntary burning ye house of anothr by night or by day & is a felony treason in Ireland”; “Murder in Ireld is treason, but not so in Engd”).

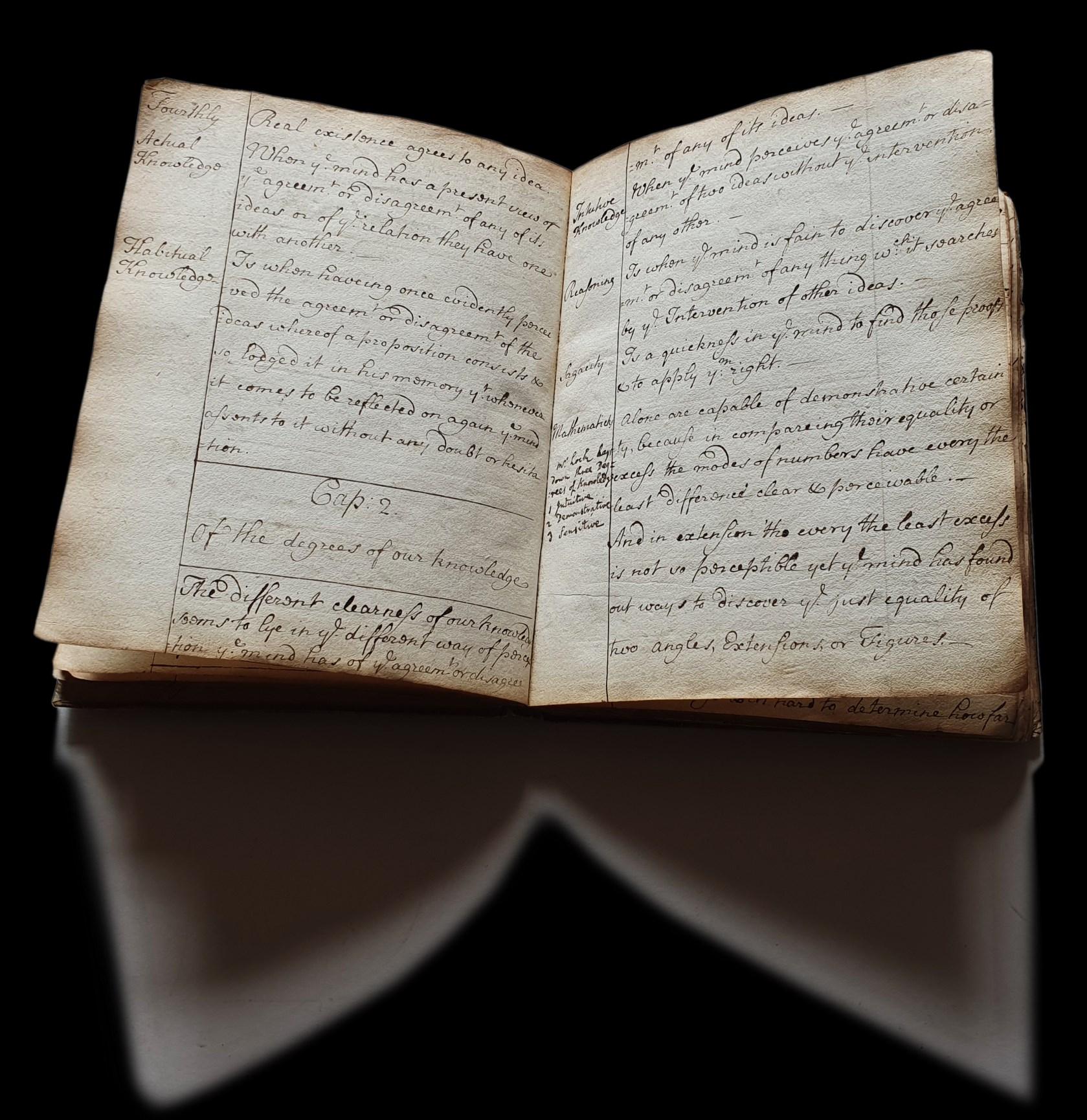

FILLED WITH IDEAS

At the opposite end of the volume, Callaghan sets down a précis of John Locke’s Essay on Human Understanding (1st ed. 1690) in just over 100 pages. Locke’s great philosophical work is arranged in four “books”: Book I (refutation of innate ideas) comprises four chapters; Book II (how we acquire knowledge) has 33 chapters; Book III (the importance of language in relation to knowledge) has 11 chapters; Book IV (what can and cannot be known) has 21 chapters.

Callaghan elides the first book –presumably because he takes the argument against innate ideas as given – and moves straight to how ideas are acquired. All chapters of Books II and III are summarised, together with chapters 1-10 of Book IV. It appears he had not finished the summaries because the title of chapter 11 has been entered but not précised. Each chapter is neatly summarised anywhere between half a page and two pages. He also includes marginalia to aid finding subjects at speed: for example, Chapter I of Book II begins “Of Ideas in general and their original. Whatever is ye object of ye understanding when a man thinks; or whatever ye mind is employ’d about in thinking”, and has the side note: “What is meant by ye term Idea”.

The summary that follows is interesting because, rather than summarising, as we might have expected, Locke’s second paragraph (positing that all ideas come from sensation or reflection), it recapitulates the argument against innate ideas (contained in Book I): “It is an establish’d opinion amongst some that these are certain innate ideas principles, as it were stamp’d upon the mind of man which ye soul brings into the world wth it.” Then in lighter (presumably later) ink, he adds “but this opinion is entirely refuted in the first book of this Essay”; and a side note reads “How do Ideas come into ye mind”.

Given the evenness of the text, Callaghan appears to have accomplished the task over a relatively short period of time. His summaries are clear and succinct and offer a fascinating insight into the reception and practical utility of Locke’s ideas. The book itself is clearly a practical aid, in more ways than one: a note on the cover commands that it is “To be kept”, declaring its lasting usefulness; meanwhile, a scattered handful of memos to the pastedowns include a reminder of on Fryday night” –philosophers, and human beings in general, must grapple with.

Callaghan’s volume offers a remarkably active witness to legal studies in England and Ireland and the discipline’s concern with the perennial subjects of property ownership and the taking of life; and it presents a fascinating dimension with its insight into the reception and application of Locke’s philosophy in the early 18th century.

SOLD Ref: 8055

References:

Elias. A. C. (Ed.) Memoirs of Laetitia Pilkington. 1997. Alumni Dublinenses: a register of the students, graduates, professors and provosts of Trinity College in the University of Dublin (1593-1860).

<https://digitalcollections.tcd.ie/concern/works/70795b624>

<https://www.myheritage.com/research/record-1-252618751-2-788/cornelius-ocallaghan-in-myheritage-family-trees>

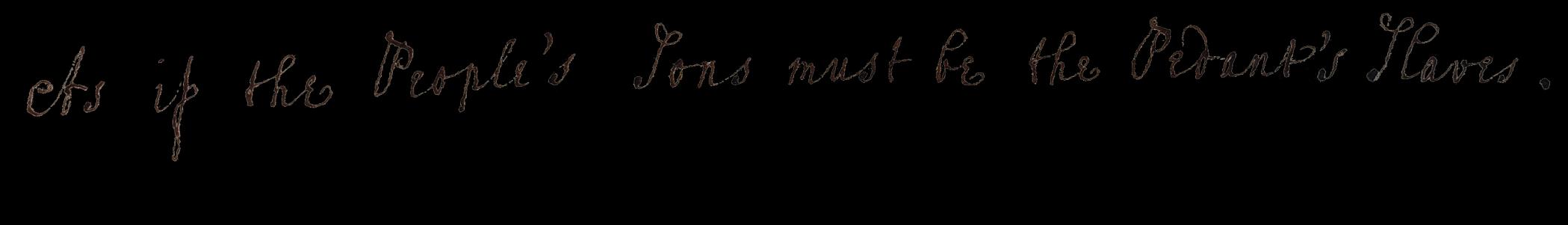

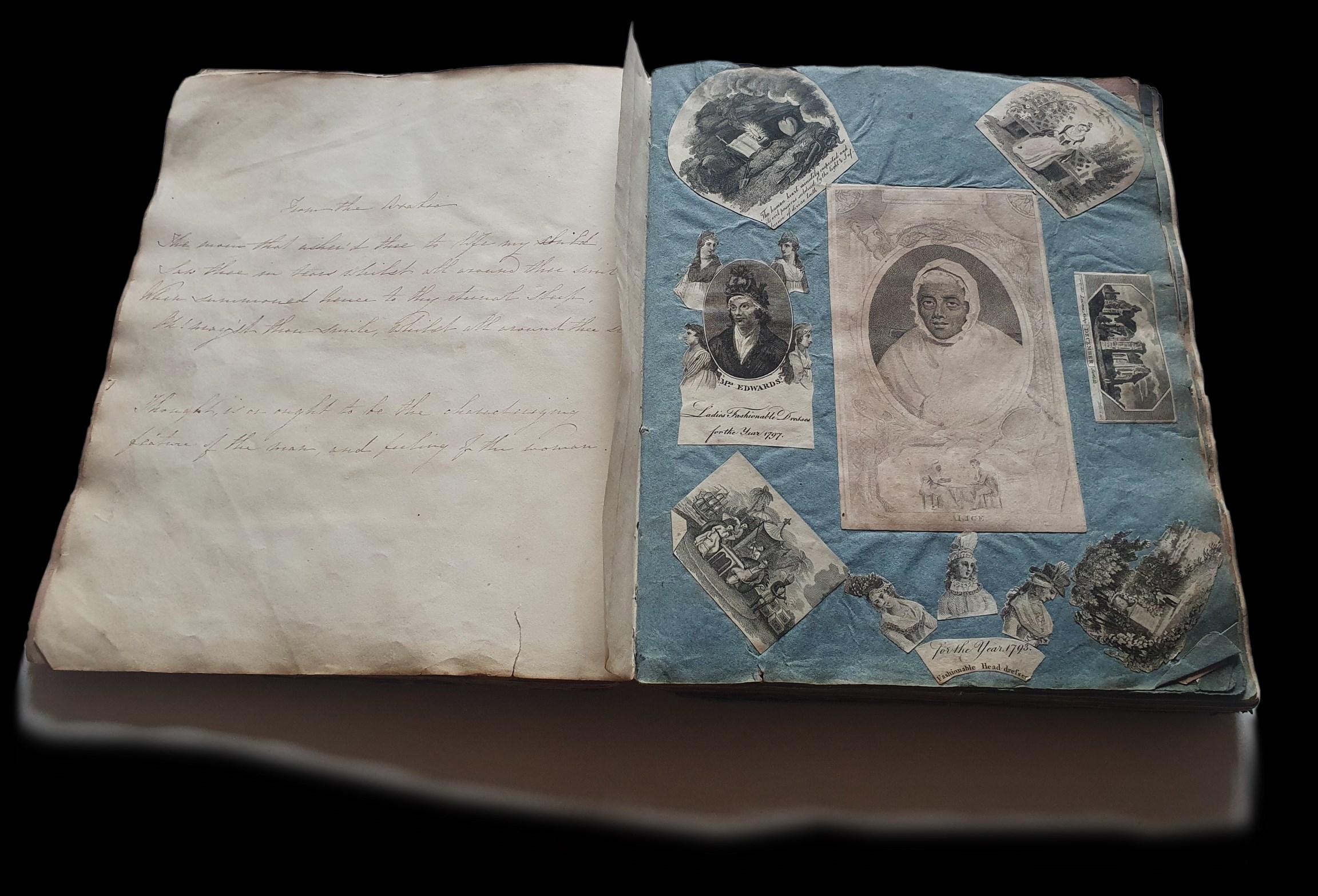

9. A PERSONAL PERSPECTIVE

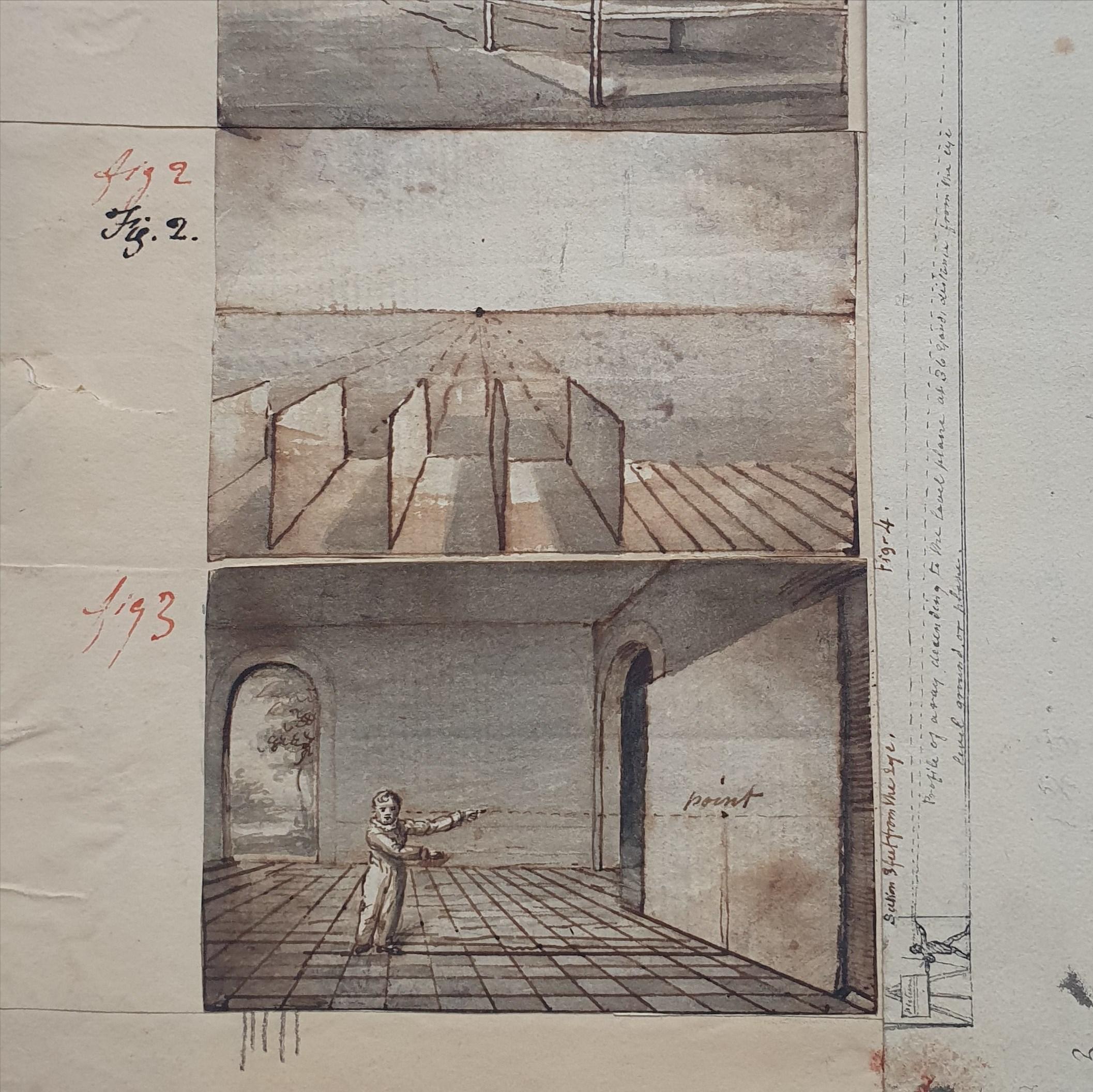

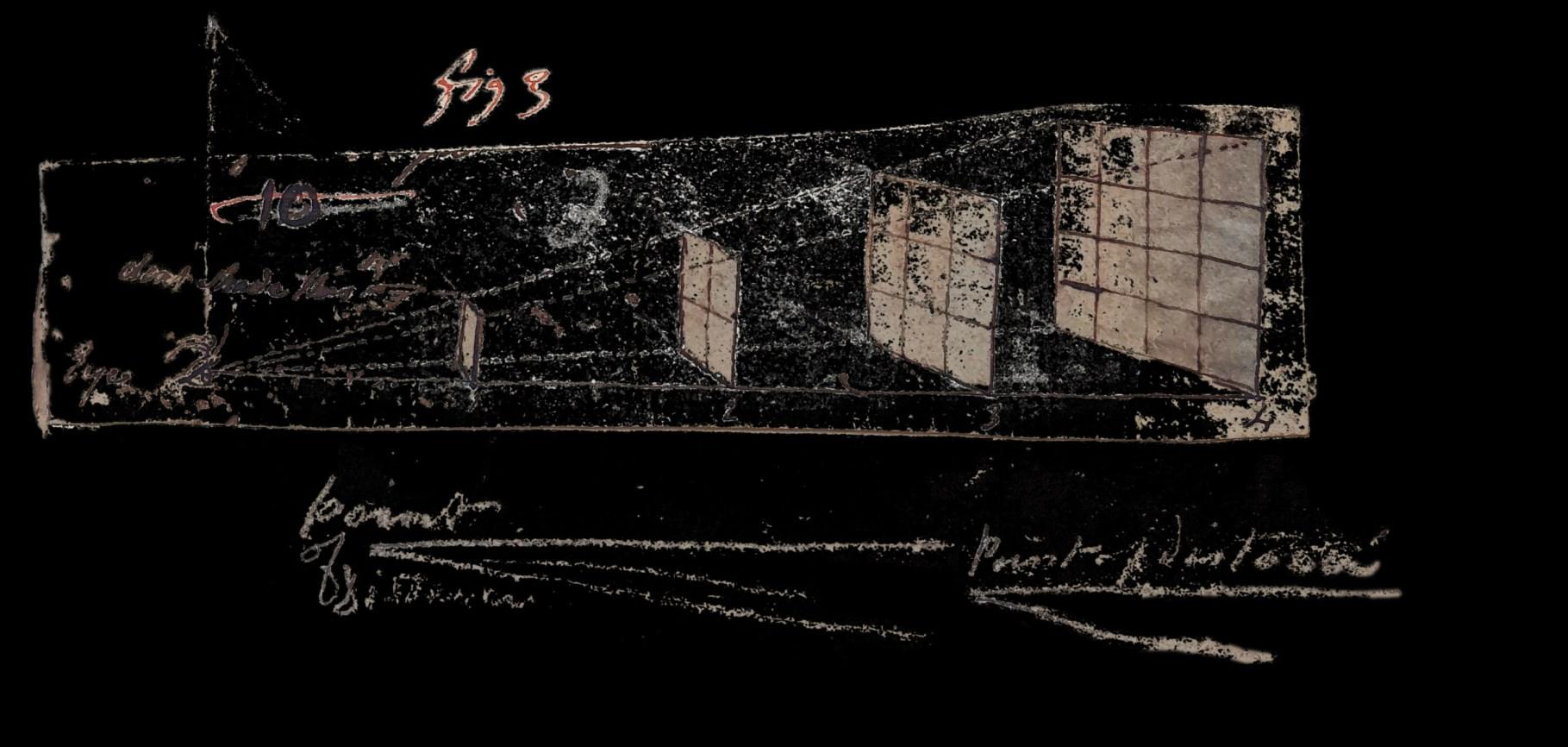

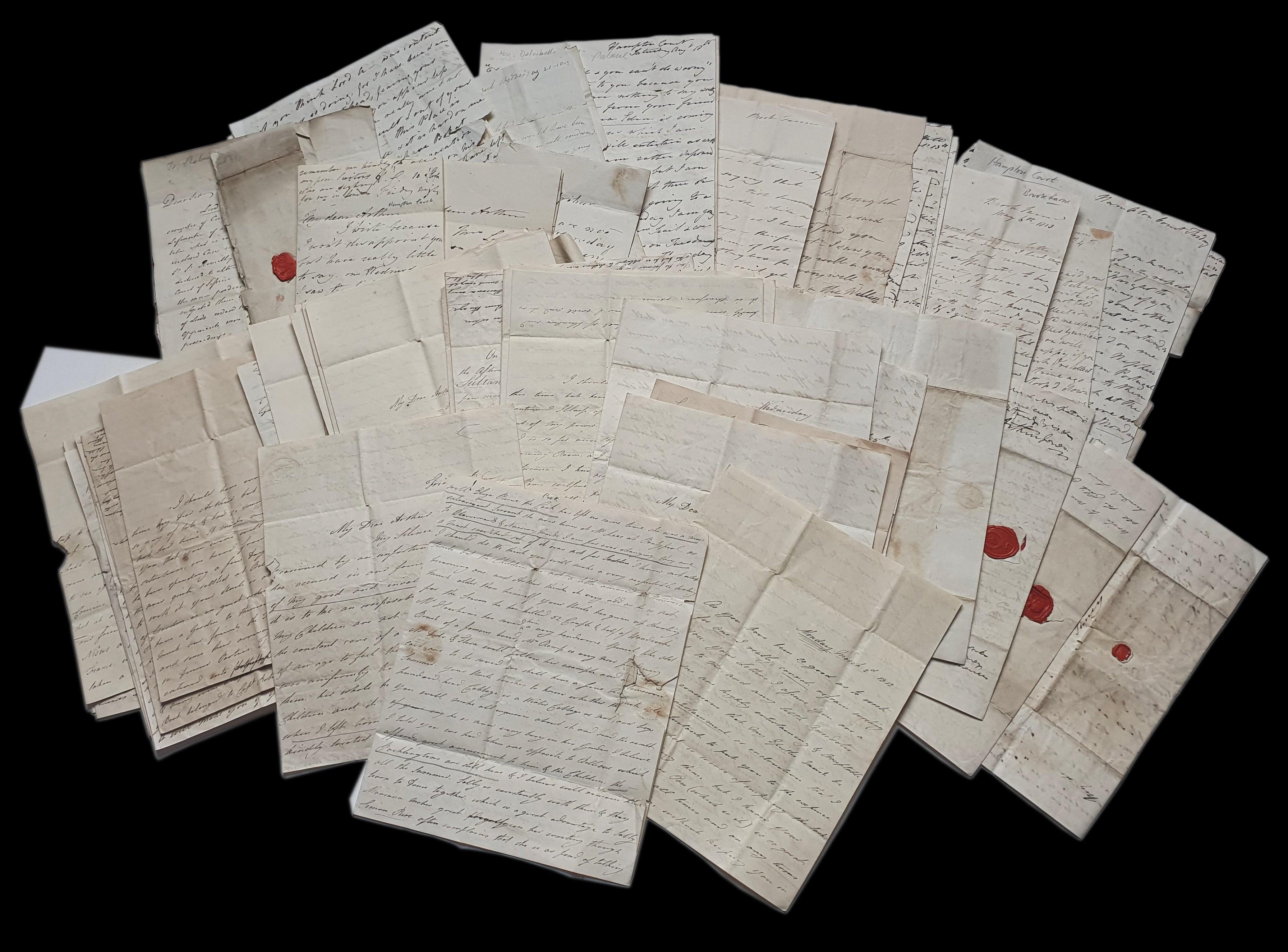

[HAYTER, Charles (1761-1835); HAYTER, Sir George (1792-1871)]. Original working manuscript on perspective.

[Circa 1804]. Quarto (195 x 165 x 10 mm). 35 text pages and a few pencil or crayon sketches on 24 leaves, with 15 pen and ink drawings and one engraved plate loosely inserted.

Contemporary vellum, soiled, text block loosening, some leaves excised. Manuscript calligraphic inscription to cover of “G” or “C” “Hayter. Vol. 5th 1804”. Inscription to pastedown reads “The Works of my dear Father Charles Hayter (John Hayter his son)” with several pen trials. An inscription to the pastedown at the opposite end reads “George Hayter”.

¶ This manuscript, which seems to have emerged out of the Hayter family’s home education, records its own evolution into Charles Hayter’s first published work: An Introduction to perspective (1813), a book which retained intact many of the personal notes found here.

The Hayters were a highly successful and mutually supportive artistic family. Charles Hayter (1761–1835), himself the son of an architect, studied at the Royal Academy Schools in London and developed a reputation as a fine miniature painter. In 1788, he married Martha Stevenson (1762-1805). They had two sons and a daughter, all practising artists: Sir George Hayter (17921871); John Hayter (1800-1895), a portrait and subject painter who exhibited between 1815 and 1879 at the Royal Academy and the British Institution; and Anne Hayter (fl. 1814-1830), who worked as a miniature painter.

Such an independent-minded family could not be entirely without conflict: Charles and his son George had an early falling out (the latter stormed off to become a midshipman), but they soon recovered their relationship and continued their work together. Indeed, according to the ODNB, Charles “came to rely” on his eldest son, “who remained at home without benefit of formal education [ ...] as a young lad he had a thirst for knowledge” and instead availing himself of “his father's skills as a teacher of geometry and perspective for artists [...] In copying his father's pencil portraits Hayter developed his skill as a draughtsman”.

Our assumption is that this manuscript was initially created as part of his children’s education, but that Charles soon saw its wider potential. Support for this theory comes from retention of certain personal references, together with changes which ‘translate’ certain details from the particular to the general.

The manuscript begins “My Dear George”, which reinforces the impression of having been originally written in “Dilogue” for personal use between Charles’s children. A note on the endpaper lists the characters as “George”, “Ann”, “Eliza” and “John”. These all refer to family members: Charles’ mother’s name was Elizabeth, and the others are his children. There are clear signs of adaptation from a familial to a general readership: for example, the instruction to “look steady up Edward Street” loses its local reference after the address is amended simply to “out”.

The text opens with a (heavily revised) question by Papa My Father tell you it would be that you Drawings would never be worth looking at impossible for you to paint original pictures if you did not make yourself thoro’ Master of Perspective, & pay the utmost attention to its rules” asks “will you tell me how to begin”. George replies you the meaning of the Word Per Perspective is the art of drawing on a surface, objects as they appear to us in nature” that Charles taught George, it seems probable not only that he also taught his other children, but that George, too, was (as this “Dilogue” implies) an active participant in their education; and Charles took this question-and-answer form, and even the names of his children, into his later published work.

Midway through, the volume has been flipped round to encompass a page and half of draft attempts at what became part of the Introduction to perspective. The text begins “The pleasure and improvement I shall derive in proving any rendering knowing that this most rational and delightful means of employing a spare hour”. This has been struck out with two vertical lines, and he begins again: “The pleasure to be derived from the practice of so fine an art, this most rational and delightful to

the refinement of ^that Taste” – and continues onto the next page. The text includes further crossings out, but what remains uncut closely resembles part of the final published text.

The illustrations are so similar to those in the published book that it seems highly likely they were directly copied from this manuscript. There are 15 loosely inserted drawings, ranging from quick sketches and diagrams to flawless vignettes which could pass for the finished article. Many are executed on little scraps of paper (some clipped from the backs of letters or other sketches) which are cut and pasted into combinations, annotated and their respective plate numbers changed, giving strong material evidence of a work in progress.

The artistic materiality is carried though into illustrations that occur within the text, one of which includes a perspective diagram with flap illustration overlaid. This detailed pen and wash is even more appealing for having been carefully rendered on a small fragment of paper cut from a letter, and complements the overall sense of transition between the personal and public contexts that this manuscript captures in striking

SOLD Ref: 8121

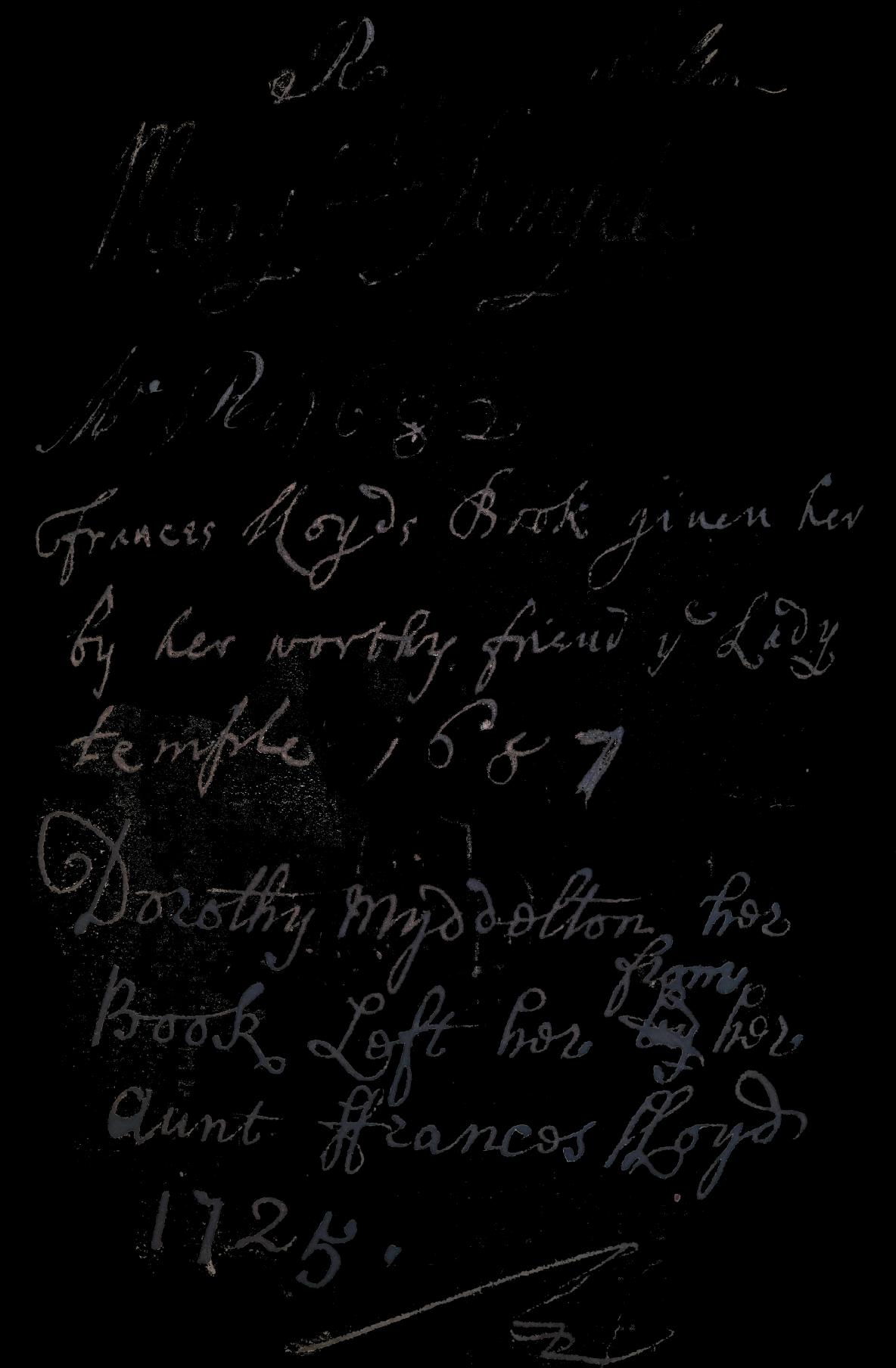

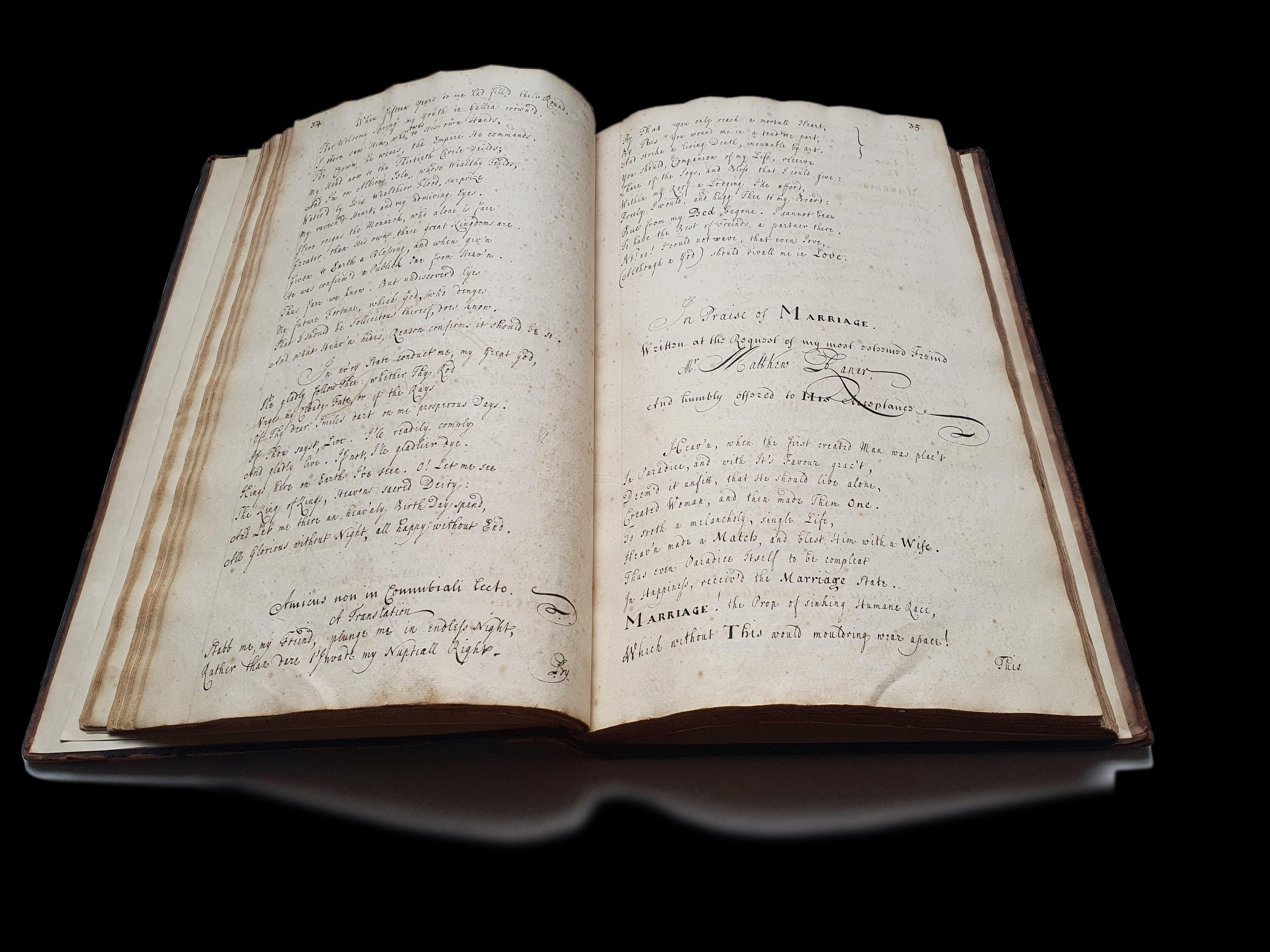

10. THE BUNS & THE BEES

[RECEIPT BOOK] manuscript book of culinary recipes.

[Circa 1843-1880]. Quarto (205 x 70 x 18 mm).

Approximately 75 text pages, 54 blank leaves. Calf-backed marbled boards with manuscript title to front board, spine damaged with large areas of loss. Some scuffing to front board, spotting and minor marks to text.

¶ This 129-page recipe book with six loose-leaf remedies is written in multiple hands. Culinary and household medical recipes are interspersed throughout. The culinary recipes include “M Soyer’s soup for the poor”, “American Cake”, “Buns for Breakfast”, “German Bread”, “French Pudding”, “Ginger Wine”, and “Calves feet jelly”. The volume also contains remedies for “a cold on the chest”, “for deafness”, and “hooping cough”, and recipes “to prevent milk from tasting of turnips” and “to prevent horses being teased by flies” Most of the recipes are attributed, many to “Mrs Sawle”, “Lady Rycroft” and “Mrs Tucker”. Some recipes are sourced from printed publications. For example, to “destroy scaly insects” is taken from Horticultural Cabinet;. “Directions for managing hive and bees”, on the other hand, have a more direct attribution: “Gale Glass hive maker, Alton”.

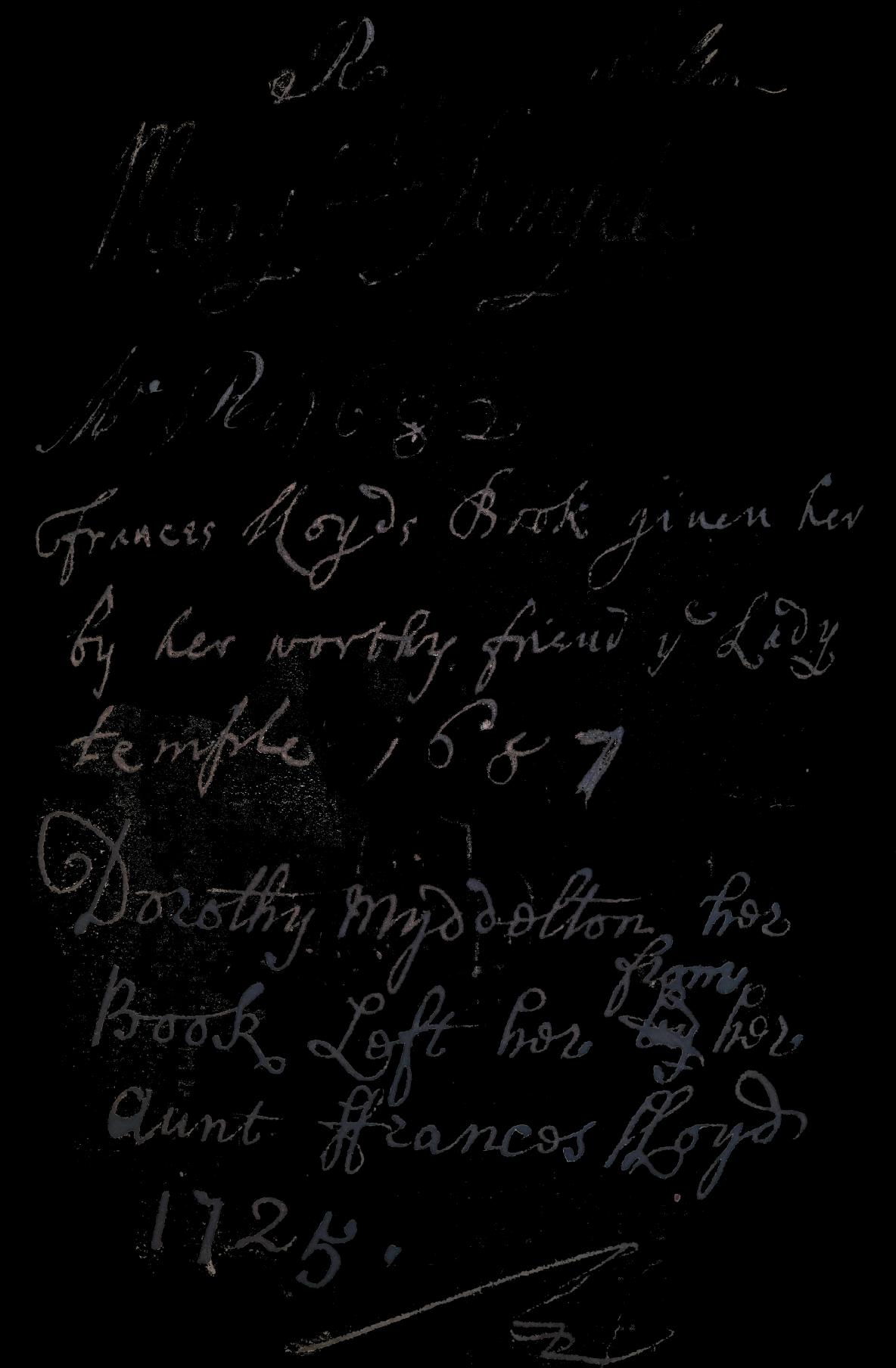

11. MOTHER’S APPROVAL

[CULINARY RECIPES] Early 19th-century manuscript book of culinary recipes.

[Circa 1810]. Quarto (204 x 70 x 17 mm). Approximately 97 text pages (of which 11 are pasted in recipes), 12 blank leaves. Vellum-backed marbled boards. Stitching broken, text block loose in biding. Boards heavily worn, some spotting to text.

¶ A note to the front paste-down reads “My Mother’s approved receipts”, but this notebook is written in multiple hands. Culinary recipes are at the front; remedies and calculations for managing a household are written from the back. The culinary recipes include “Shrewsbury Cakes”, “India Pickle”, “Fruit Acid” and “Diamond Cement”. The volume also contains calculations for budgeting and managing a household, such as a sum for “the value of 152/2 Gallons of Brandy”. Dispersed throughout the calculations are a few household recipes, such as one “For French Polish” The recipes have clearly been used, with those found unsatisfactory crossed through or labelled “Bad Bad.” Most of the recipes are unattributed, but a few are taken from printed publications, e.g. “Wine from immature grapes” is meticulously attributed to “Remarks on the Art of making Wine by Macculloch 2d Edition”, complete with the publisher’s details.

£400 Ref: 8138

£300 Ref: 8137

12. HOME PRIME

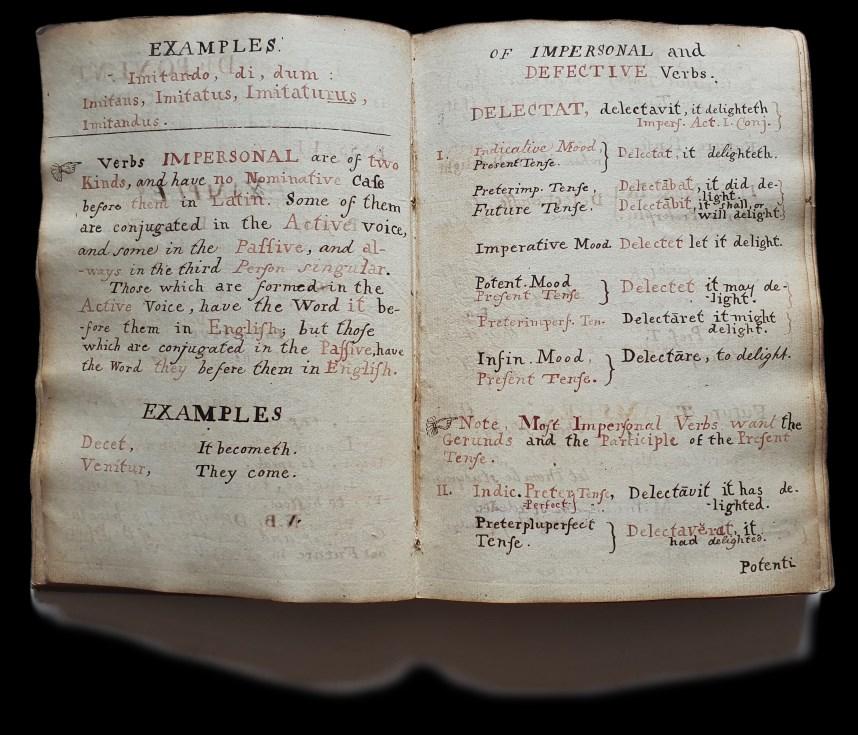

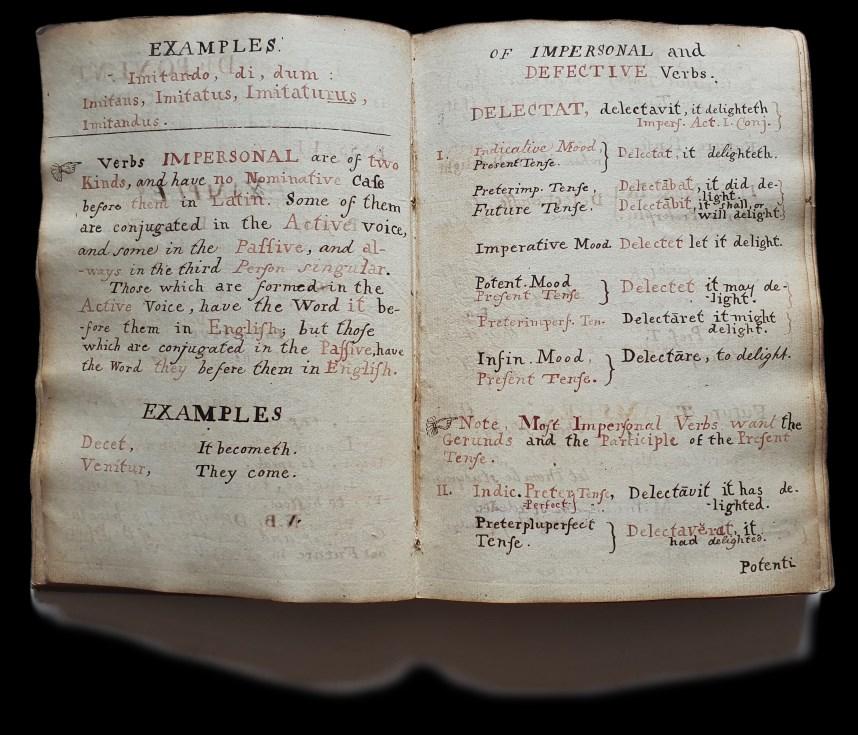

[ASTLE, Daniel] 18th-century manuscript Latin primer.

[Derby. Circa 1782]. Quarto (206 x 143 x 27 mm).

Approximately 277 text pages on 141 leaves (including paste -downs, but lacking front endpaper), which continues onto the paste-downs. Stationer’s vellum-bound notebook, spine damaged with loss to upper and lower section, ghost marks of old tape repairs to spine and boards. Inscription to front paste-down reads “2d: Danl: Astle Bought this Book at Derby Augst 21st 1782.”

¶ This exceptionally neat manuscript provides an insight into the levels of literacy that might be expected of young scholars in the early modern period. The text is written in a very clear hand in red and black ink throughout, with some of the neatest manicules we’ve ever seen. It begins with “A Caution in making Latin”, which commends books used “for Latin Exercises”, but advises that “young Scholars” must learn the “manner of Construction” in Latin, hence the need for this manuscript. Topics treated include “Of the Sign of the Genetive”, “Conjugation of Verbs”, examples of “A Verb Deponent”, “Clark’s Rules for Translating”, and “General Rules respecting the Declension of Nouns”.

Later in the manuscript we learn that the “young Scholars” are “my dear George and William”, so it seems highly probable that this is an artefact of home education.

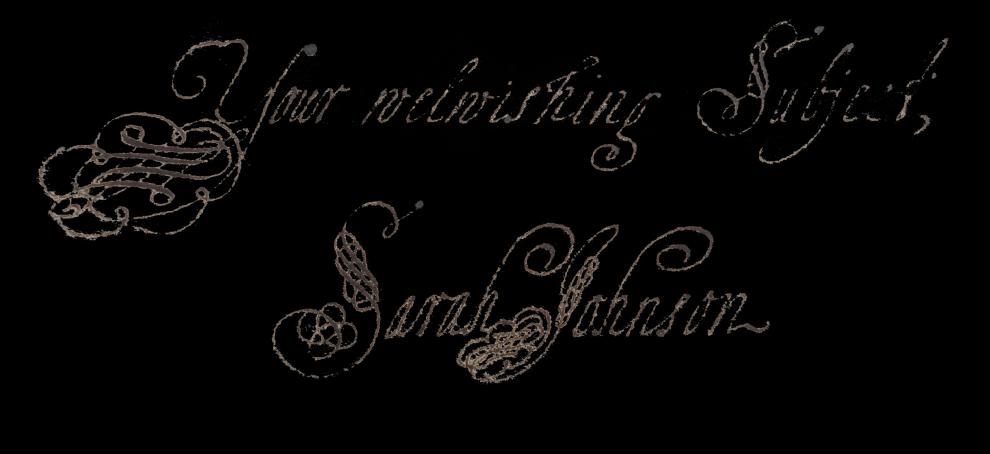

13. A WOMAN’S PRIDE

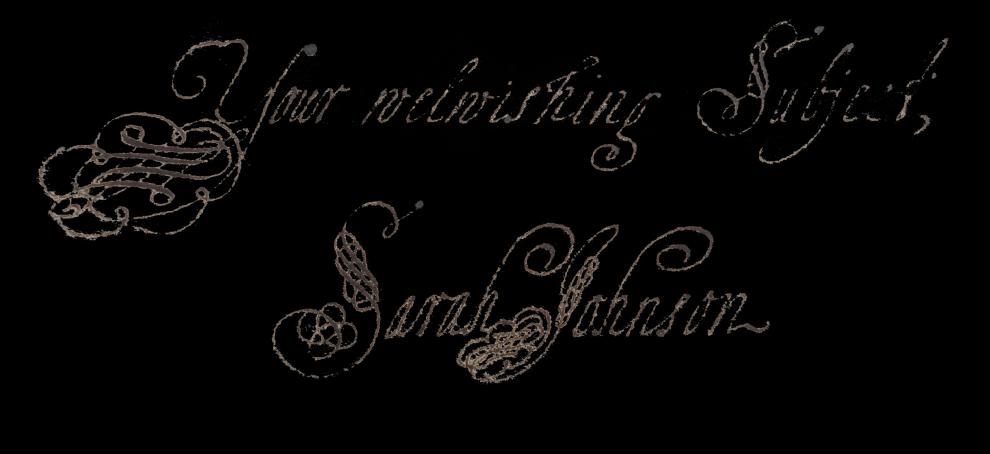

[JOHNSON, Sarah] 17th-century manuscript account of a revelation presented to Queen Mary.

[Circa 1692]. Bifolium (sheet measures 345 x 230mm). Two text pages. Docketed: “A copy of Sarah Johnsons message to ye present queen 1692”.

Watermark: Royal Arms of England, within a shield and surmounted with a crown.

SOLD

Ref: 8107

¶ This account provides an intriguing insight into attitudes towards a woman’s voice when she is considered God’s messenger. “Sarah Johnson” apparently travelled from her “abode in Ireland” to present Queen Mary with her “revelation of his Spirit”, in which she witnessed a vision of “3 Lions furiously fighting”. Sarah interpreted this as “3 Kings wth their Armies vizt. ye K of France, K. James & K Wm” – and it is the latter, Mary’s Protestant husband, who triumphs. The text is accompanied by copies of an account (initialled “WT”) of her audience with the queen, which she was granted despite her apparent lack of social status. She forthrightly warns of impending “wrath of the almighty” and demands that the King and Queen “discourage the support of crying sins” and show “humility”; and if they doubt that her authority is divinely sent, she invokes the testimony of her “neighbours & acquaintances” Despite Johnson’s audacity, it seems she was treated in a “courteous and friendly” manner throughout.

SOLD Ref: 8140

GREY’S COLOURS

[GREY, John (d.1709)] Early manuscript inventory entitled “A true and perfect Inventorie of the goods and Chattells of John Grey Esqr: Late of Howick in the County of Northumberland deceased”.

[Howick, Northumberland. Circa 1709]. Single sheet of paper folded to make a strip 415 mm x 325 mm with conjugate blank. Text to one and a half sides.

This detailed tally of one man’s worldly goods provides a striking contrast with the minimal and mostly functional possessions usually recorded in such early modern inventories. John Grey was evidently well to do: the inventory, recorded after his death in June 1673, begins with his “apparell, purse, watch, Swords & pistols, and furniture for his pad”. Soon we encounter everal rooms defined by colour: “blew roome”, whose contents include “blew Curtins” and “blew hangings”, and a “gray Roome”, which contains at least three pairs of “Curtins”, but none of them grey; followed by a “stript Roome”, which features “printed Curtins” and “6 Turkey work

Further indications of relative prosperity occur throughout the inventory. “high granary” there are “two servants bedsteads”, and elsewhere we find a “silver Tankerd & 5 silver spoons”, a “damask table Cloth & 1 dozen damask napkins”, an abundance of bedding, and a kitchen stocked with the likes of “4 spits […] 3 dozen pewter plates […] 5 pair of tongs”, and “3 small guns”. Meanwhile, in the “Seller” are “Barrells great and small 30 and one Hogshead &20 dozen of bottels & one old press”, and “in the Milkhouse 31 milk tubs ^2 Cheese tubs 2 Churns 6 firkins”.

This plentiful evidence of a busy working household continues outside, with livestock including “51 milk Ewes”, “45 Lambs”, “12 swine”, “6 kine”, “6 Calves”, and much more besides. John Grey seems also to have attended to his inner life, to judge by the presence “in his own Closet” of “133 books price – 05.00.00”. His total wealth is initially estimated at “514.03.09”, then reduced on “15th May 1710” (almost a year later) to “the sum of 469.00.8” –for reasons not recorded.

SOLD Ref: 8139

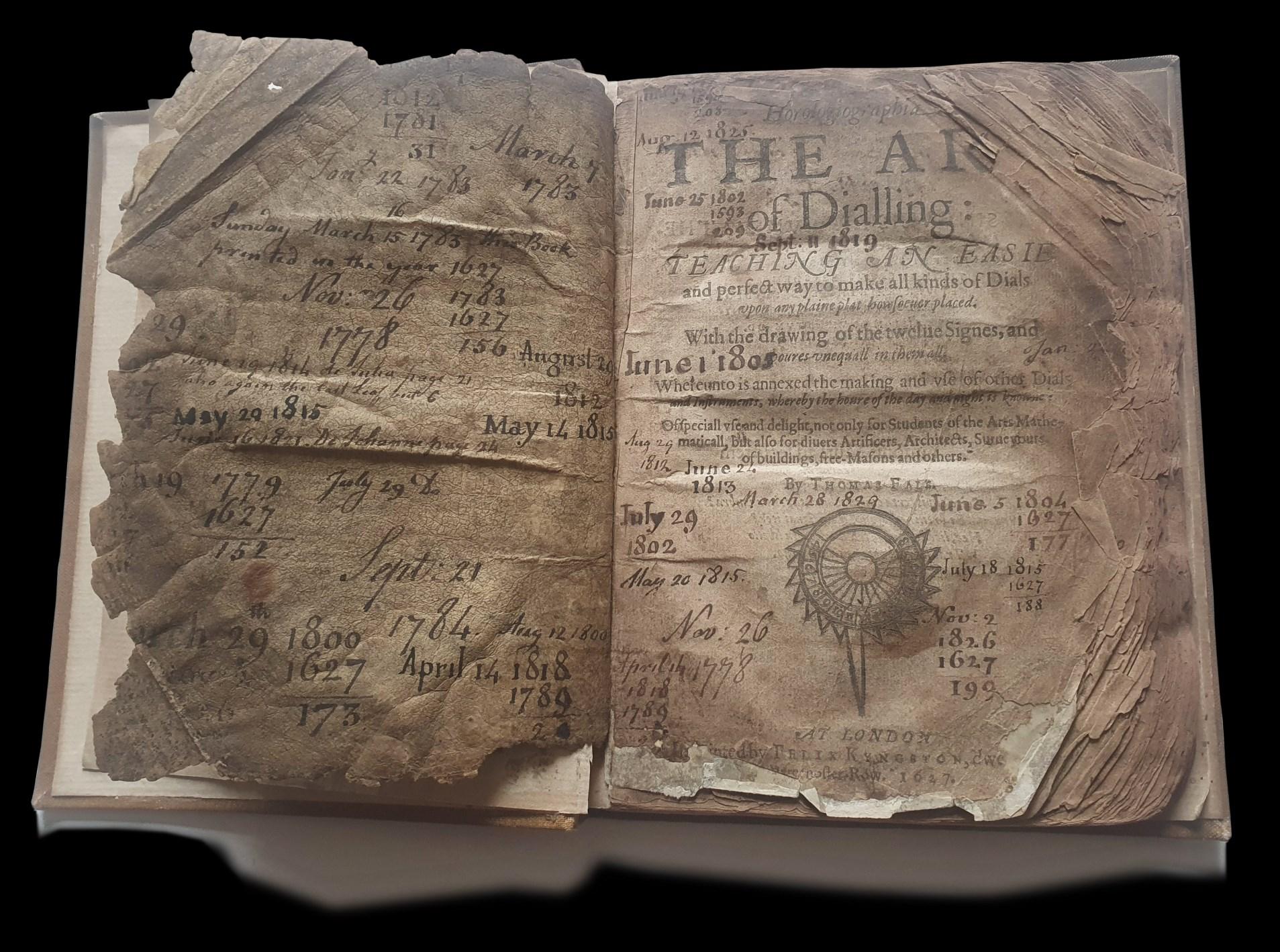

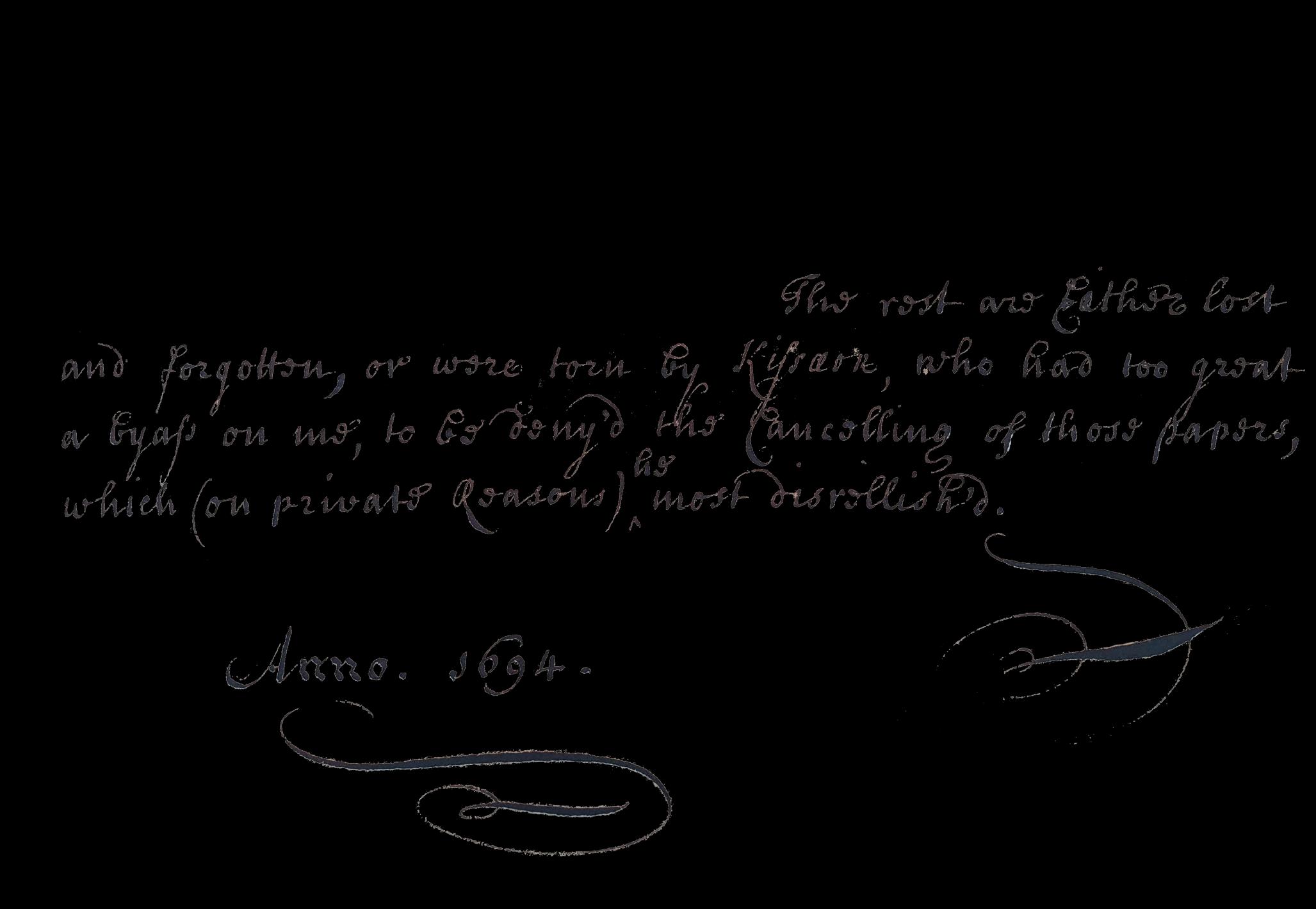

14.

FORGOTTEN THINGS

SMITH, John 17th-century manuscript entitled ‘A true and pfect Inventory of the goods and chattles of John Smith of the pishe of ffarmeborrow in the County of Sondsett yeoman deceased taken and prised by Richard Short Samuell Smart & John weekes the sixteenth day of June and in the yeare of our Lord God 1673.’

[Farmborough, Somerset. Circa 1673]. Single skin (410 x 195 mm), folded. Vellum.

¶ The worldly goods belonging to a 17th-century yeoman, indeed to anyone below the level of gentry, tended to cater only to the basic necessities of sitting, sleeping, and eating. Such is the case with “John Smith of the pishe of ffarmeborrow in the County of Sondsett”, whose inventory, recorded after his death in June 1673, is a reminder of the austere norms of ownership for a yeoman in the early modern period.

The appraisers, moving through Smith’s house and assigning a value to everything in pounds, shillings and pence, begin by noting “his weareing apparrell 05-00-00” (clothing being a fourth necessity), and “money in his purse and due uppon bond 48-10-00”. In the hall they record “one table board three chaires six joyne stooles one side board one cupboard 02 00”, and in the kitchen, items including “one furnace one brasse pann fower kittles […] one paire of andirons […] one dripping pann”.

Smith’s work on the land is well represented, from “corne in the Mowbarten in the howse and corne growing uppon the ground 15-00-00” and “one cart” and “plow harness” healthy smallholding’s worth of livestock that includes Kine and a Bull 25-00-00”, “twenty two sheepes and lambs 04 00-00”, “six stales of bees 01-10-00”, and the nonspecific “three young beasts 04-00-00”. The inventory is rounded off with the sum of “04-09-00” which is “due to the deceased” from a debtor, and with the mopping up of “things forgotten 00-03-04”, Smith’s total wealth is given as “153 01-04”.

SOLD Ref: 8031

15.

JACOBITE

[JACOBITE MANUSCRIPT] Hybrid manuscript entitled “Ane Colection of Meditations & Prayers &c. Especialy such as are proper to be us’d before, at, and after receivig the Holy Sacracment of the Lords Supper for my own Privat Use”.

[Moray and London. 1686-1724]. Octavo (text block measures 56 x 96 x 26 mm). Pagination [2, title], 10, [2], 11-146, [5], [3, blanks], 147-260, 263-314, [7, “Table”], 315-321. Despite the absence of pp261/2, the text appears to be complete. Frontispiece, and 24 engravings (some full page, but most within text), one of which is hand coloured. 19th century calf, marbled endpapers, rebacked (probably 20th century), metal clasps, all edges gilt. Inscription to the fore edge reads “Morray 1724”.

¶ Collaging, copying, adaptation, and original composition all combine in this volume to chart a series of textual and physical journeys. Our scribe assembles a patchwork of illustrations and published text, together with their own thoughts, that resembles a collage, whether in terms of the object’s construction, the text’s fragmented narrative or its author’s geographical journey.

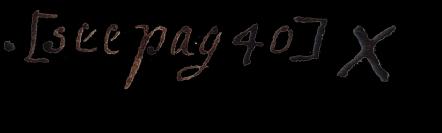

The disruption of chronology offers a series of trails that reflect the unsettled nature of the scribe’s own physical movement from the conception of the text to its conclusion in 1724. There is no clear, set order in which to read this manuscript: instead, the scribe gives us a range of interconnected textual routes through and around the manuscript. For example, near the end of p14 we are instructed to “(see) pag i8, 22”, and a few lines later to “(see) pag. 115”. The former direction takes us to “A Prayer”, which calls upon God to “assist me by thy H: Spirit yt my preparations […] be as exact as if I were to stand before ye Thron of my Eternal Judge” and “be admitted to the Marriage supper of the Lamb” before guiding us to “see page (38.) (39)” – and, beneath it, “A Caution as to our Preparation” enjoins us to “[see pag 40]”.

Page 38 takes us to page 254; page 39 returns us to page 18. But, before we breathe a sigh of relief at having closed one textual circle, we should remember we have only followed one of three paths set out on page 18: we have yet to visit pages 22 and 115 (the latter of which presents still further onward journeys). Meanwhile, if we’ve followed p38’s instruction, p254 presents the “Prayer to Holy Jesus” which cries “O Crusified Jes: my only hope & refuge! bath me in thy Blood beautifie me wth thy Merits” and then directs us to “see pag 37”, where the reader encounters a very similar cry “O My crucified Jesu!”, before directing us back to p254 – creating an endless loop of messianic suffering.

The majority of directions, however, offer the reader several different routes through the text: the prayer on page 22 refers the reader to no fewer than seven places (“pages. 18: 22: 38: 39: 25: 66: i48:”). This unusual combination of choice and direction disrupts normal sequential reading; because the options could always be combined differently, just one different page turn alters the sequence, resulting in a proliferation of possible routes and readings.

The manuscript’s title page can itself be interpreted as a map charting the book’s creation, apparently over 38 years: it was, a note reads, “begun in London 1686”. At this time, James (1633-1701) was King of England and Ireland as James II, and King

16. HYBRID

of Scotland as James VII, having succeeded his elder brother, Charles II, in 1685. James was deposed in the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and fled to France in 1689; a further note on a later page suggests that this manuscript followed him and was “Used by me when in France 1690 & 1691”, then “ended 1724 Morray” – a trajectory (London-France-Scotland) that shadows the fate of the Jacobite cause and suggests that our scribe may well have been a Jacobite.

EDITING

Their identity remains elusive, but their sources suggest a complex mentality informed by Protestant, Catholic and occasionally secular texts. The scribe’s justification for compiling this text is provided in the preface: “If the deretions of Solomon […] may be look’d upon as safe & sufficient Guids” ~ “Any who has scruples […] lett them read Doctor Combers Preface to his Companion to the Temple, and if they do so (without prejudice) it will certainly convince them of their error.” Thomas Comber’s (1645-1699) Companion to the Temple (1st ed. 1672), was intended to reconcile Protestant dissenters to the church of England. A small pamphlet inserted between pages 146 and 147 entitled “For a right use of the H: S: by BP Ken”, is copied from the English non-juring bishop Thomas Ken’s (1637-1711) An exposition on the church-catechism, or The practice of divine love (1st ed.1685), and “Scots Christian Life” (p95) refers to the Anglican clergyman John Scott (1639-1695).

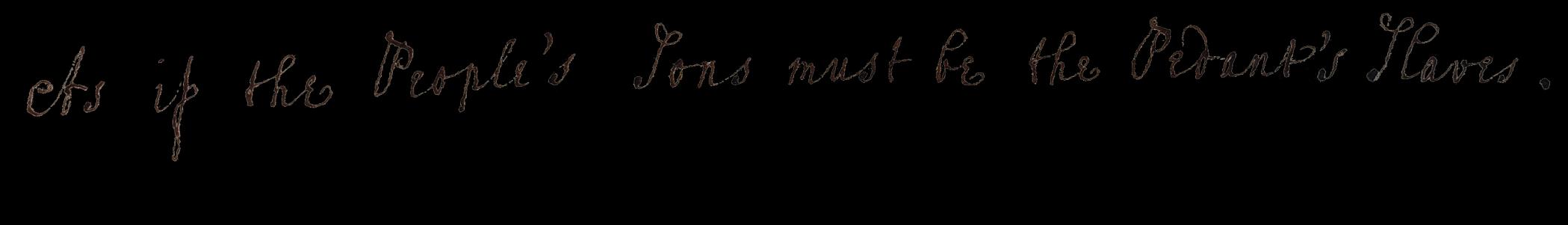

Various saints feature (“St. Mechtildis” on p40; “St. Austin” on p108; “St. August:[ine]” and “St. Bern:[ard]” on p290), and “Seneca tho a Heathen” (p291) is admitted as an honorary or proto-Christian, in order to offer some Stoic wisdom. Despite such displays of wide reading, the scribe, while discussing those “dubious in oppinion in matters of Religion”, implores that God “free me from all prejudice [especialy yt of Education]”, echoing a distrust of education expressed earlier, in a poem (p7) which reads: “By Education we are all misled, / Some believe, because we were so bred: /Mass John continues wt ye Nurse began, /And thus ye Child imposes on the Man”. This reconstructs lines from Dryden’s recently published poem The Hind and the Panther (1687), while other entries appear to be unpublished, or at least so recomposed as to elude easy identification.

Another bit of “editorialising” is particularly noteworthy: on p287 the scribe observes that “There are excellent, and Devot Prayers, to be had out of ye Auther of the whole Duty of Man, before & after examination.” But they appear to have thought better of this recommendation and have neatly pasted over it a slip of paper (since partly lifted) declaring “An Act of Contrition to be made before & after our Examination & solemne Confession of our sins to Almighty God in order to our Receiving ye Holy Eucharist.” It seems that our author, like the routes one follows in their book, is prepared to go back and change course later.

CUTTING AND PASTING

What sets this manuscript apart is its use of the conventions (and even clippings) of the printed book. The title page adopts several of these practices (centring and varying the size of the text, place and date[s] of “publication”), and there are red borders and running titles throughout. An engraved frontispiece is only the first of many engraved illustrations, including “Christ brought before Herod” (p172) by William Faithorne (www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1857-1212-244 –though the text differs from that recorded in the British Library Catalogue) and a full-page illustration titled in manuscript “Christs Resurrection” (p223) which retains the name of the artist (LaVergne). In this latter image, our inventive scribe has utilised an area depicting a blank stone tablet to insert – very neatly – apposite Biblical quotations and notes. This integration of the scribe’s own identity with the existing illustration makes for an alluring visual.

Their seeming adherence to the conventions of the printed book has some notable exceptions: on the page after the illustration mentioned above is another, hand-titled “Christ Ascendeth into Heaven” (p224), which is entirely bordered around with manuscript Biblical quotations (this practice begins with the first illustration after the frontispiece, on p8, which has also been hand-coloured). While the form of the printed book provided an initial guide for the scribe’s feelings, its boundaries were no match for their compulsion to break out into blizzards of text if they were so moved.

All of these elements – the selection and collaging of different sources and materials, the multiple textual paths on offer, the suggestions of a difficult journey undertaken by the book itself and its author – combine to produce a quite remarkable and hugely appealing hybrid artefact.

SOLD Ref: 8094

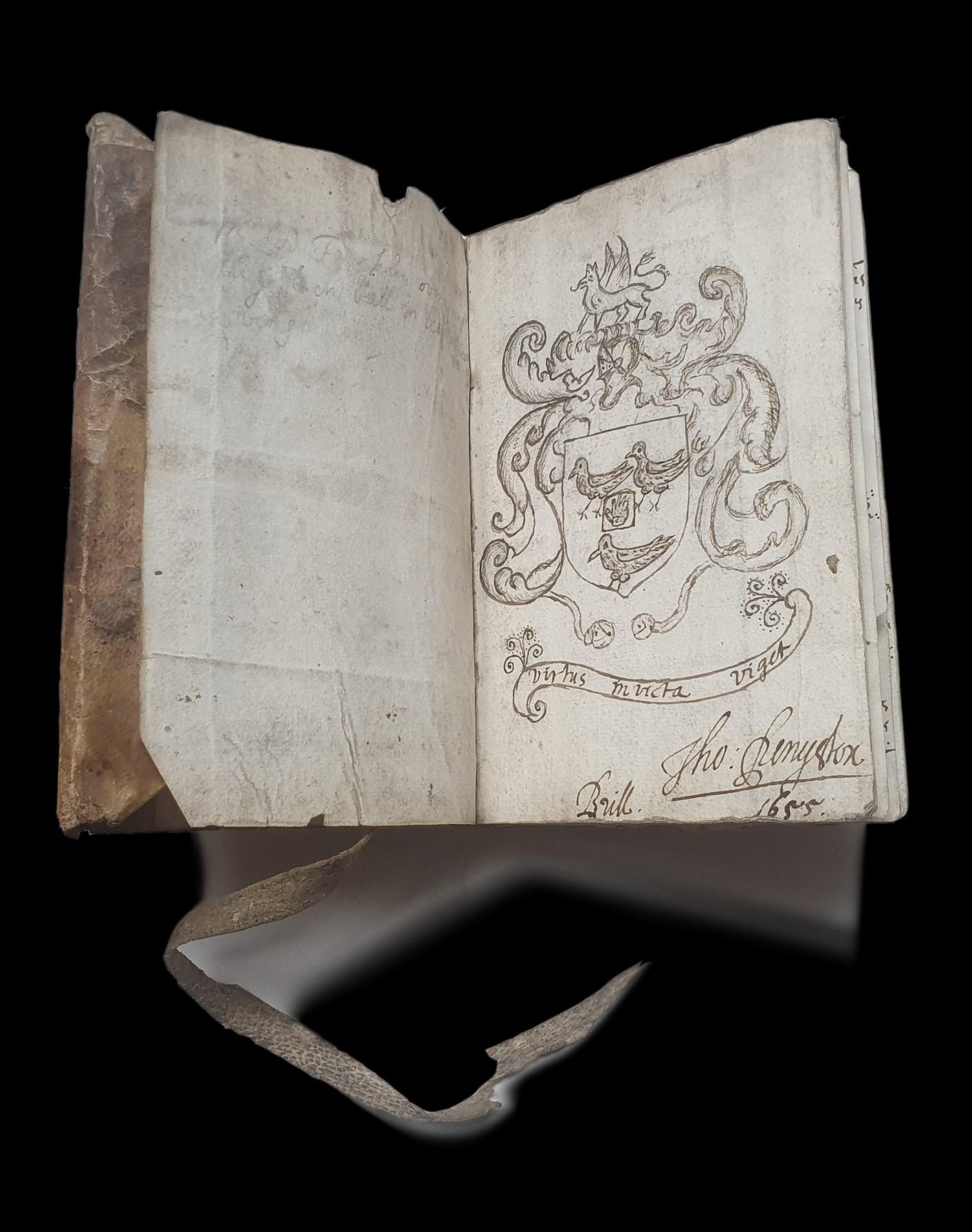

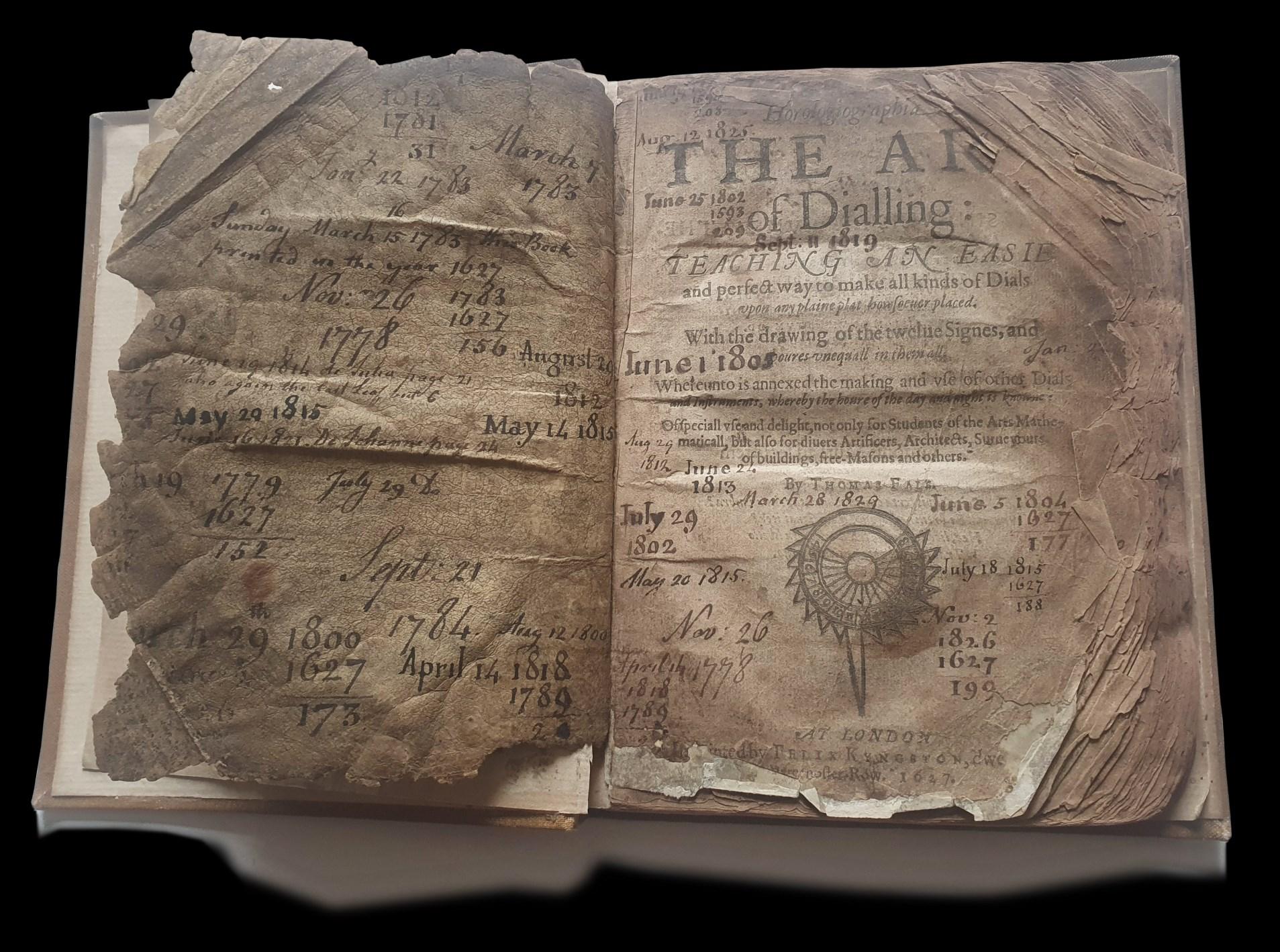

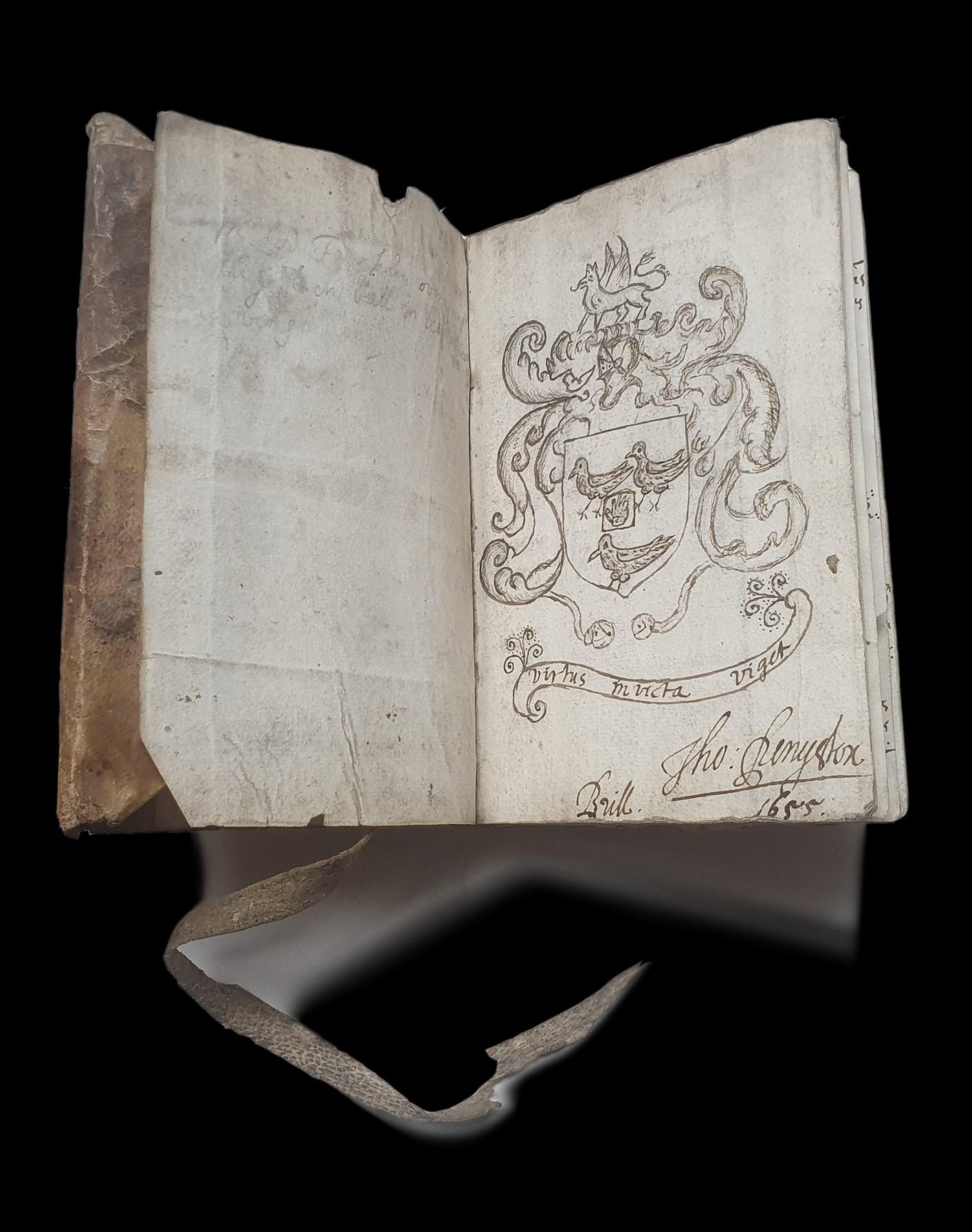

17. INTO THE WOODS

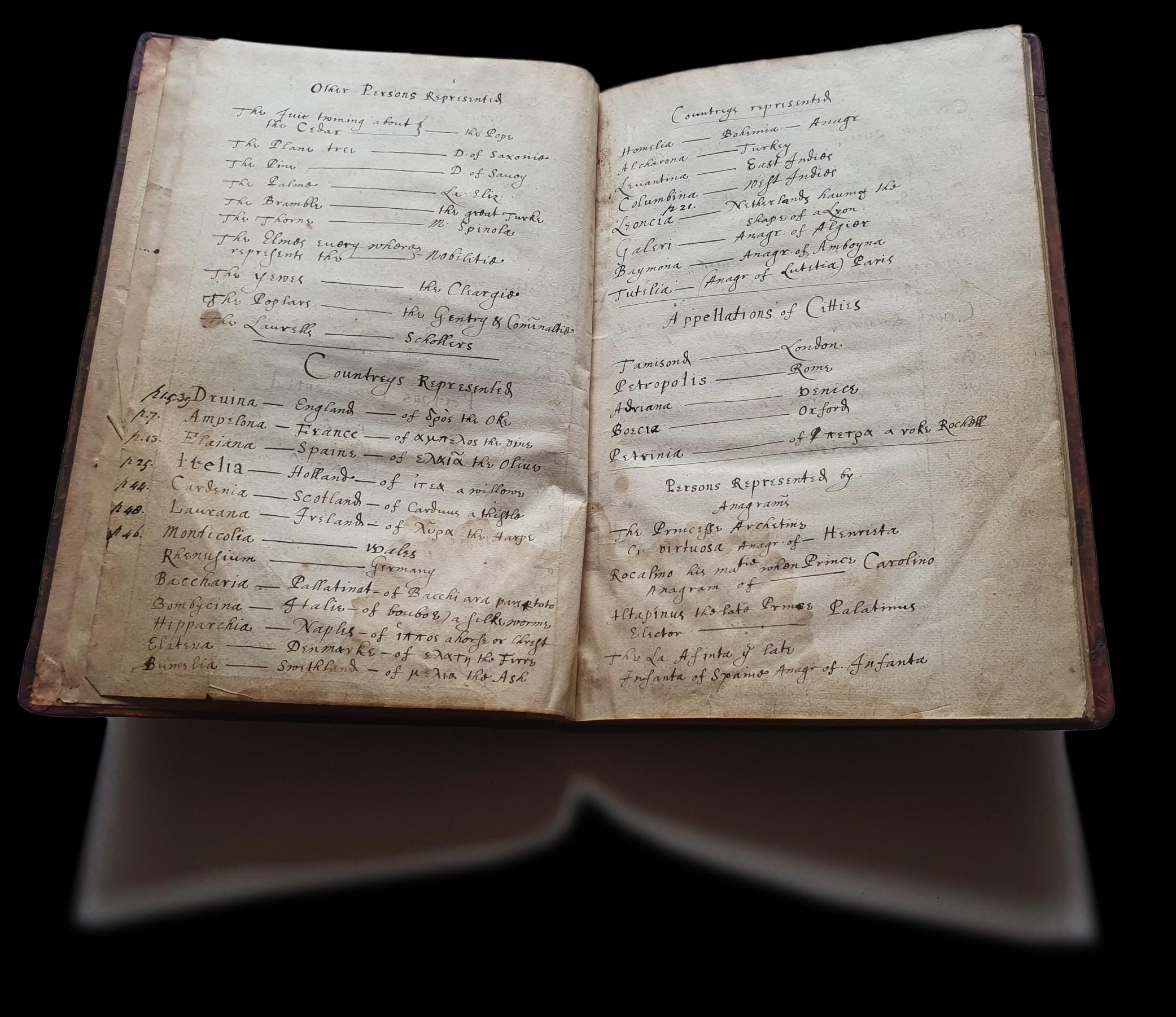

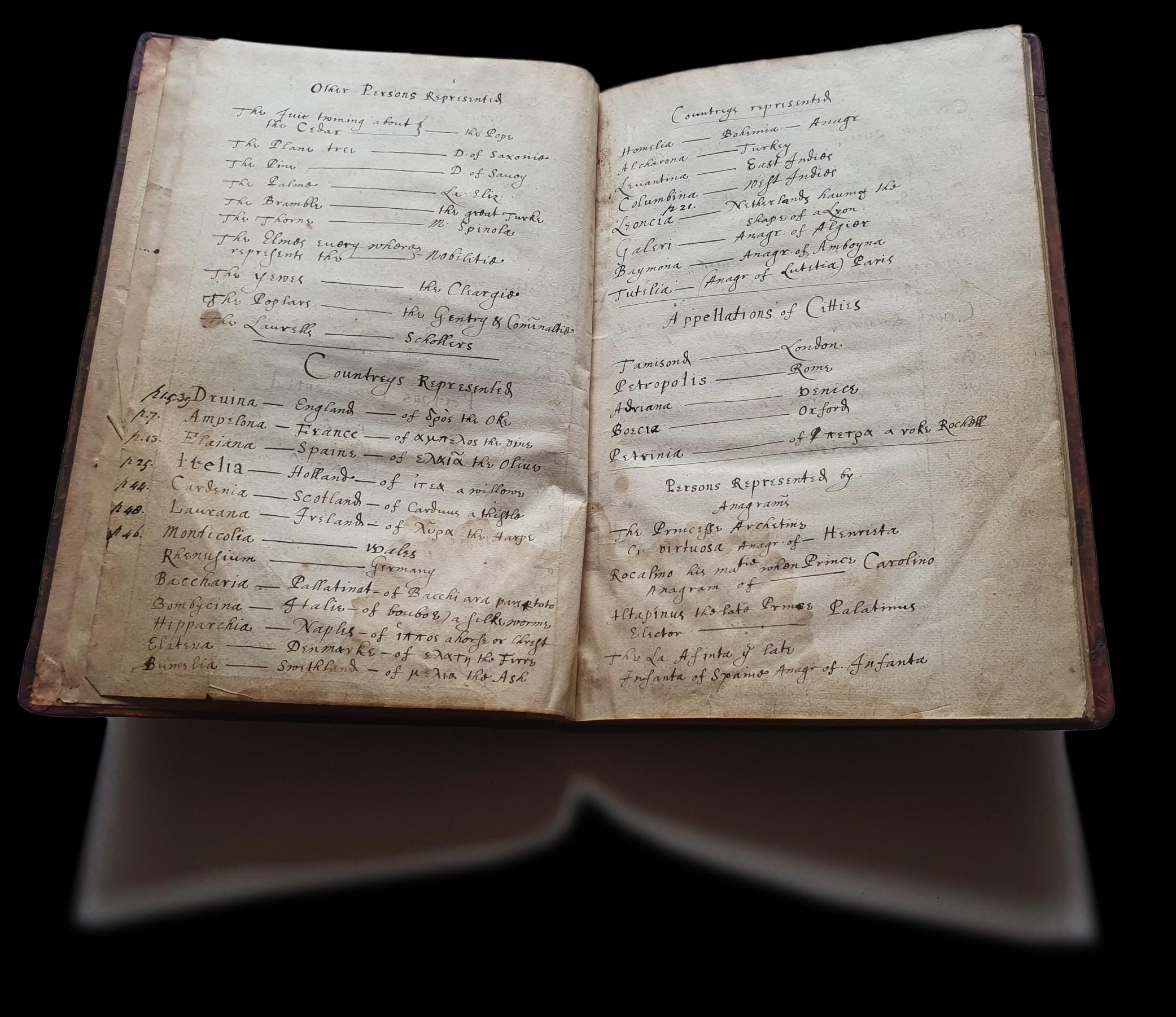

HOWELL, James (1594?-1666); Mary CHIVER. Dendrologia. Dodona’s grove, or, the vocall forrest. By I.H. Esqr

[London : Printed] By: T[homas]: B[adger]: for H: Mosley at the Princes Armes in St Paules Church-yard, 1640. First edition. Folio. [12], 32, 39-135, 166-219, [1] p., [2] leaves of plates. 18th-century full calf, recently rebacked and recornered. Damp stain to text throughout, plates torn with small areas of loss to, neatly laid down, closed tears to frontis and final text leaf, both repaired without loss.

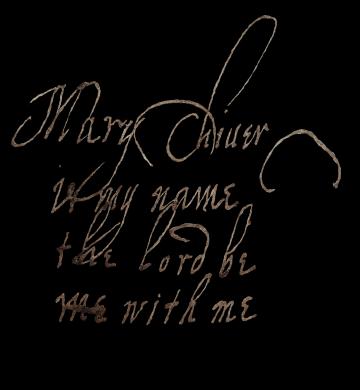

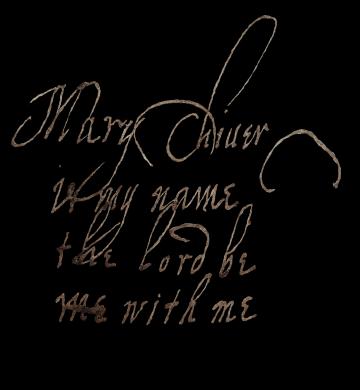

Provenance: 17th-century ownership inscriptions of “Mary Chiuer” to front free endpaper and lower margin of final text leaf. Two inscriptions to title page: “Mary” and “Robert Chiuer”. A pencil-note to the paste-down claims, without any justification, that this is the author’s own copy.

¶ In Dodona’s Grove, an allegorical poem by the 17th-century Anglo-Welsh historian and political writer James Howell, prominent figures and groups are represented by trees and other plants in order to comment on events in Europe, particularly England, between 1603 and 1640. The political criticisms in Howell’s work may have been a causal factor in his incarceration in Fleet Prison from 1643 to 1651 (although financial insolvency was the given reason).

This copy of the first edition of Dodona’s Grove has annotations and manuscript notes, by one or both of the book’s early owners, Chiuer”, and “Robert Ciuer” who unpick Howell’s allegory, demonstrating in the process a high degree of erudition. The annotations to the front free endpaper make free use of phrases from the Book of Psalms and Genesis, and combine them with personal reflections:

Leading a Life without all strife in quiet rest and peace, from envy and from malice both or hearts and tongues to cease which if wee do then sch all we shew,

Feare not mary for thou hast found fāuar with god

Well may it bee saide

Mary bee not a fraide

And all his sonnes and all his daughters Rose up to comforte him : but hee refused to be comeforted; and hee saide I will goe doune to the graue.

Mary Chiuer is my name the lord be me with me

Immediately after this, two leaves of manuscript notes have been bound in. This paper is watermarked: Crozier (Haewood 1219, which he dates 1634/5) and the hand is commensurate with the time of publication – ie, the 1640s. The notes, written in a clear, confident hand, decode Howell’s allegory: A Parley held by Trees in the Vocall Forest. The reall Subject.

Under the shaddowe of Trees s couchd a mixt Methodologicall Discoure {Theologicall

Partly {Politicall {Historicall

Reflecting upon the greatest Actions of Christendome, since the yeare sixteene hundred and three (viz: from the beginning of his later maties raigne in England to the very Epoche, sixteene hundred, and fortie