TRIUMPHANT!

ROLAND BROWN

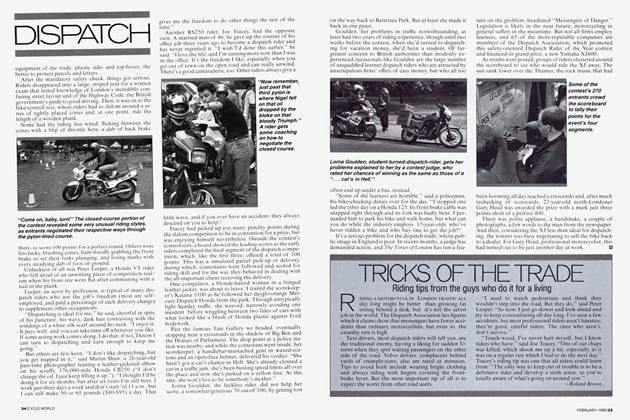

THE SENSATIONS ARE FAMILIAR. Blipping the throttle at a standstill, the noise is a blend of gear whine and the muted tone of an inline-Four's exhaust. The 16-valve engine spins smoothly and effortlessly, an instant surge of acceleration available at the flick of a wrist. Braking for a corner, the big machine slows hard, and is rock-steady as it is eased into the turn with a light nudge on the handlebars.

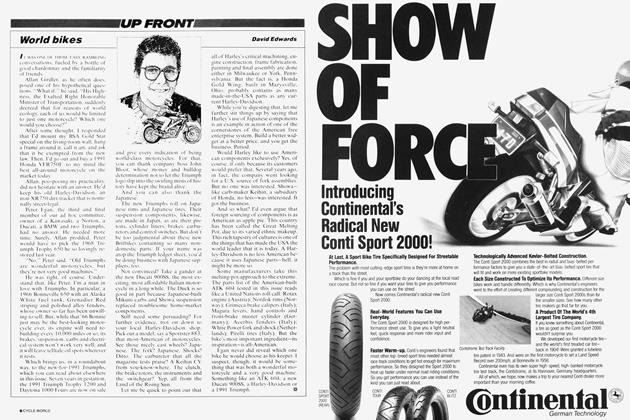

Then, suddenly, the realization strikes: This isn't some new Japanese machine; it isn't the product of years of gradual refinement bv one of the w'orld's major manufacturers. No. This is a Triumph, one of the first products of a British company that has returned from the grave, an allnew multi-cylinder superbike.

Motorcycles bearing the new Triumph logo went on sale in Germany and Britain a few months ago. and it is little more than a year since the factory gates first w ere opened to reveal ultra-modern lines of huge computer-controlled machining centers, a battery of frame-welding and paintspraying robots, and a state-of-theart assembly line. It is from that line that bikes now are rolling at a rate of almost 100 per week, with a target of double that number in the future.

The British are back in a big way

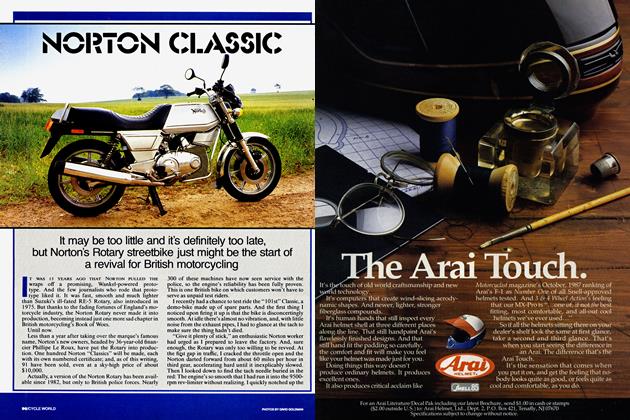

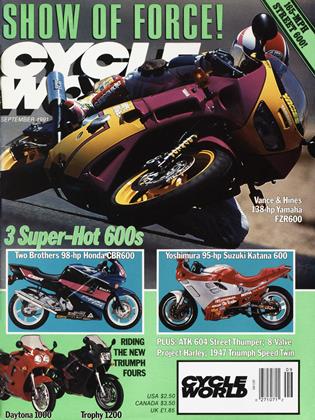

For seven years, barely a rumor had emerged from Triumph's anonymous gray buildings on a modern industrial estate in the English Midlands, just a few miles from the housing development where the old Triumph works at Meriden once stood. And now, finally, here are the first two models, the Daytona 1000 and Trophy 1200 (a standard-style Trident will come later), ready to compete head-on with the best motorcycles in the world.

Both have liquid-cooled, four-cylinder engines, conventional chassis and full fairings. They look much like Japanese Fours, they sound like Japanese Fours, and they're built like Japanese Fours. Some long-time Triumph enthusiasts might grumble that the marque's traditional character has been abandoned, and others might complain about a lack of originality. But the men behind the new Triumphs will not worry about that.

These are thoroughly modern superbikes, from the tips of their windscreens to the footprints of their fat, low-profile radial tires. Maybe there is a touch of Kawasaki styling in the shape of the Trophy’s fairing; perhaps the twin-headlamp Daytona is reminiscent of the early Suzuki GSX-R. But Triumph is the name on the gas tank of each, and the name that rises boldly from the crankcase and cylinder-head castings. And, with a little luck, it just might be the name that will reform the identity of the oft-maligned British motorcycle.

Daytona 1000

Triumph is going after the sporttouring crowd with the l I80cc Trophy, but the 988cc Daytona 1000 is intended as a more serious sportbike.

Enthusiasts who remember Triumph's glory days in the late 1960s and early '70s will not require an explanation for that model name. T riumph Twins and Triples had plenty of success at the famed Florida trioval, and a lovely 500cc street Twin bore the name until the company hit hard times in the early '70s. This new machine's name is its only link with the past, however.

The 998cc engine is a short-stroke variation of the modular engine design that all three new Triumphs, in six engine sizes, will use. It is a revvy unit, its l l ,000-rpm redline marked l 500 rpm higher than the long-stroke Trophy's. Compression ratio is I l:l, compared to the 10.6:1 of the Trophy. Peak pow'er, a claimed 119 horsepower at 10,500 rpm. is down from the 123 produced by the Trophy's bigger motor, and the maximum torque figure of 65 footpounds also is a bit low'er. But apart from its silencers, which are slightly less restrictive than those hung on the Trophy, almost every other enginerelated part, including the carbs, is identical.

As an Open-class sportbike, the Daytona gets the chassis parts it deserves, including a multi-adjustable Kayaba fork and four-piston Nissin calipers gripping 12.6-inch, fully floating discs.

In the cockpit, behind the twinheadlamp upper fairing, the Daytona's clip-on bars are mounted sportbike-low. below the top triple-clamp. But Triumph takes pains to insist that the Daytona is not a repli-racer, but is, instead, a “sports roadster." Certainly the riding position is far from a track-ready crouch. You lean forward only slightly to the clip-ons, a position that makes the Daytona's riding position seem roomy and maybe even a little old-fashioned.

On the move, the bike is anything but old-fashioned. Its engine is smooth, with a rev-happy flavor. A twist of the wrist delivers crisp, instant acceleration whenever 5000 rpm or more shows on the tach. An indicated 150 mph is easy, thanks to that wonderful engine and to the bike’s very efficient fairing. Twisty roads, where speeds rise and fall, offer no complication—the bike's gearbox is very slick.

The chassis is equally impressive. In their standard position, the Daytona's Kayaba fork legs protrude a few millimeters through the yokes, while the Trophy’s fit flush. This makes the Daytona's steering marginally quicker then the Trophy’s. Though not of the currently favored upsidedown design, the fork has excellent action and is fully adjustable for compression and rebound damping, as well as spring preload. And there is no faulting the potent Nissin front binders, w hich require the lightest of touches on the lever to deliver superbly controllable stopping.

Ground clearance is all most riders will require, though the Daytona's exhaust eventually will scrape pavement if the bike is leaned over far enough. On a track, that would lose the Triumph time to a GSX-R 1 100 or a FZR1000, though the heavier British bike, perhaps 10 mph slower on top speed and probably half-a-second down on quarter-mile performance, would be struggling to keep up. anyway.

But such comparisons are unfair to the Daytona. It was intended to compete with other Open-class bikes on the road, not on the track. And it does that quite nicely.

Trophy 1200

The Trophy is at once very like the Daytona, and at the same time, very different from it. Triumph originally claimed that the Trophy w'ould develop I4l horsepower, but that figure has since been modified to 123 at 9000 rpm. just below the 125-horsepower limit imposed voluntarily by the British bike importers, and very dose to the figures claimed for the Suzuki Katana I 100 and the Yamaha I J 1200. at which the Trophy is clearly aimed.

Throw a leg over the Trophy and punch the starter button. T he engine starts instantly with a rather w'hiny sound, warms quickly and idles at an unwavering 1000 rpm. Riding position is on the aggressive side of sporttouring. with lowish handlebars, and pegs high enough to make the handlebar/footpeg/seat relationship almost identical to that of Kawasaki's ZX-1 I. At a standstill, the Trophy feels tall and. with a claimed dryweight of 529 pounds, it certainly is no lightweight.

But the weight slips away as you let out the clutch and open the throttle. The Trophy engine performs with a delightful mixture of power, tractability and smoothness. There's instant acceleration everywhere, from below 2000 rpm all the way to the 9500-rpm redime. No flat spots, just a steady stream of' torque that sends the Triumph surging towards a topspeed of' just over 150 mph and makes the excellent, six-speed gearbox almost unnecessary.

The new Triumph engines differ from many modern superbike units in that their airboxes sit behind the engines they feed, rather than above. There's no downdraft effect, and certainly no ZX-1 1-style ram-air feed to the 36mm flat-slide Mikuni carburetors. So, the Trophy cannot match, say. the ZX-1 l's 176-mph top speed or its ability to produce power wheelies with a crack of the throttle. But the T riumph carburetes superbly and has superior low-speed power delivery. making it slightly easier to ride than the big Kawasaki, and equally fast on most roads.

The engine's response is near-identical to that of the aforementioned Katana 1100 and to early-model I d 1 2s, with one exception: This engine is far smoother. Both those rival engines, solidly mounted, are distinctly buzzy. But both the Daytona and Trophy engines use a patented system of twin balancer shafts, one of which runs off the primary drive instead of the crankshaft. As a result, the high-frequency vibration typical of an inline-Four is hardly noticeable. The feel of these engines is more akin to that of this year's FJ 1 200. with its rubber-mounted engine. But the Triumph block is solidly fixed, and acts as a stressed member of a steel-tube frame that seems decidedlv dated in comparison with the latest alloy twin-beam constructions.

To that frame are bolted Kayaba suspension pieces: a non-adjustable 43mm fork and a single, vertical shock that is hydraulically adjustable for preload (by turning a bolt-head under the seat) and through four rebound-damping settings (using a hand-adjuster by the right sidepanel ). Steering geometry is fairly conservative at 27 degrees of rake and 4.1 inches of trail.

In normal use. the Trophy handled very well, playing its designated role of sport-tourer with considerable style. In a straight line, it was totally stable all the way to its 1 50-mph top speed. Only when ridden towards its cornering limits did the Trophy reveal that the sport side of its personality can't match that of the bettersuspended Daytona. On one long, sweeping curve that could be taken at a bit more than 1 20 mph, the Trophy began a slight head-shake at a point where the 1000 still would have been rock-solid.

Ground clearance was ample for road riding, but in ultra-aggressive cornering, the collector of the 4-into2 exhaust system grounded before the admirably sticky Dunlop K45 5s— the very same radial tires used on the Daytona—reached their limits. Increasing the spring preload to its maximum helped, but did not cure the problem, and resulted in a choppier ride, even when the rebound damping was increased to match.

Such limits would hamper the Trophy on a racetrack, where its brakes would also prove a slight handicap. Twin-piston Nissin calipers squeeze a pair of 1 1,6-inch discs up front, with a single 10-inch disc at the rear. T he stoppers were less powerful than the Daytona's four-piston units, but proved adequate for high-speed road riding, and their span-adjustable levers are a neat touch not found on all the Trophy’s rivals.

Most other ergonomic details are equally well thought out. The fairing, like the riding position, resembles that of recent big Kawasakis, and does an effective job of protecting the rider's chest and hands. The lowset airbox allows a fuel tank large enough to contain 6.6 gallons, good for a 200-mile-plus range. Better still, the seat is wide enough, and is sufficiently well-padded, to make such distances comfortably coverable.

T he sturdy grabrail. Japanesemade switchgear and bungee hooks below the seat are all nice touches, although the Trophy loses points in a few areas. Its mirrors are a little too small and narrow; the instruments are clear, but unfashionably bolted to the top triple clamp; the headlamp's low beam is feeble; the centerstand requires a hefty pull; and the paint finish is too easilv scratched. But those are mere details, and detract little from the Trophy’s remarkable ability to hold its ow n against the best all-around sportbikes in the world.

These two new T riumphs are more similar even than initial impressions might suggest. But both are truly outstanding. combining superb engines with chassis which, while not stateof-the-art. are very capable. The key factor in all of this is that Triumph has the resources and the production efficiency to price their bikes competitively. In Britain, the Trophy and Daytona have just gone on sale at £6849 and £6799, respectively, or. at prevailing exchange rates, $11,165 and $1 1,082. Before you gasp, you should know that in Britain, motorcycle prices are across-the-board higher than in the U.S. FJ 1200s and Katana 1 100s cost about $9300; an FZR 1000 costs about $ 1 1,400; and a BMW K100RS runs about $14.000.

Initial sales have been very good. with production already sold out for several months, so at last Triumph boss John Bloor is getting some return on his huge investment, reportedly as high as $50 million. But his spending has by no means ended. Triumph's design team is already well into the next phase of model development, and there seems to be permanent construction work going on at the factory as new buildings are added to take more operations inhouse, further increasing efficiency.

So, the outlook seems very encouraging for the born-again Triumph firm. The only bad news is that new Triumphs will not be seen in the U.S. in the near future. America's depressed motorcycle market—and its vexing product-liability laws—means that less-demanding export areas in Europe, Japan and Australia will be tackled first. Triumph is unlikely to return to the States before 1993. When it does, though, it will return with machines that should forever lay to rest those old jokes about the unreliability of British motorcycles. These new Triumphs will return to America triumphant. ga

View Full Issue

View Full Issue