PARALLEL DEVELOPMENT

RACE WATCH

YAMAHA'S FIRST-EVER SUPERBIKE CHAMPIONSHIP RESULTS FROM FINE-TUNING-OF BOTH MOTORCYCLE AND RIDER

What's your best lap time at Willow Springs?" Thomas Stevens asks me on the phone a few days prior to Cycle World's scheduled test of his championship-winning Superbike.

“Uh, a 1:32 and change,” I reply.

“Good,” Stevens says, “we’ll get you doing 27s.”

“Ummm, uh,” I babble, aghast at the thought. “I’d be ecstatic if I could turn a 1:30.”

“Heck, it’ll do that all by itself,” he says jokingly.

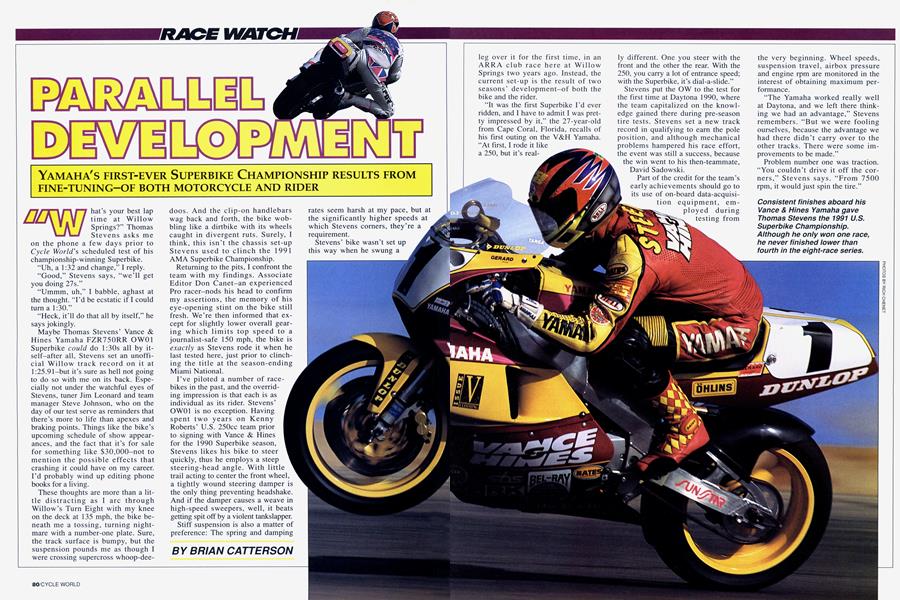

Maybe Thomas Stevens’ Vance & Hines Yamaha FZR750RR OWOl Superbike could do 1:30s all by itself-after all, Stevens set an unofficial Willow track record on it at l:25.91-but it’s sure as hell not going to do so with me on its back. Especially not under the watchful eyes of Stevens, tuner Jim Leonard and team manager Steve Johnson, who on the day of our test serve as reminders that there’s more to life than apexes and braking points. Things like the bike’s upcoming schedule of show appearances, and the fact that it’s for sale for something like $30,000-not to mention the possible effects that crashing it could have on my career. I’d probably wind up editing phone books for a living.

These thoughts are more than a little distracting as I arc through Willow’s Turn Eight with my knee on the deck at 135 mph, the bike beneath me a tossing, turning nightmare with a number-one plate. Sure, the track surface is bumpy, but the suspension pounds me as though I were crossing supercross whoop-deedoos. And the clip-on handlebars wag back and forth, the bike wobbling like a dirtbike with its wheels caught in divergent ruts. Surely, I think, this isn’t the chassis set-up Stevens used to clinch the 1991 AMA Superbike Championship.

Returning to the pits, I confront the team with my findings. Associate Editor Don Canet-an experienced Pro racer-nods his head to confirm my assertions, the memory of his eye-opening stint on the bike still fresh. We’re then informed that except for slightly lower overall gearing which limits top speed to a journalist-safe 150 mph, the bike is exactly as Stevens rode it when he last tested here, just prior to clinching the title at the season-ending Miami National.

I’ve piloted a number of racebikes in the past, and the overriding impression is that each is as individual as its rider. Stevens’ OWOl is no exception. Having spent two years on Kenny Roberts’ U.S. 250cc team prior to signing with Vance & Hines for the 1990 Superbike season, Stevens likes his bike to steer quickly, thus he employs a steep steering-head angle. With little trail acting to center the front wheel, a tightly wound steering damper is the only thing preventing headshake. And if the damper causes a weave in high-speed sweepers, well, it beats getting spit off by a violent tankslapper.

Stiff suspension is also a matter of preference: The spring and damping rates seem harsh at my pace, but at the significantly higher speeds at which Stevens corners, they’re a requirement.

Stevens’ bike wasn’t set up this way when he swung a leg over it for the first time, in an ARRA club race here at Willow Springs two years ago. Instead, the current set-up is the result of two seasons’ development-of both the bike and the rider.

BRIAN CATTERSON

“It was the first Superbike I’d ever ridden, and I have to admit I was pretty impressed by it,” the 27-year-old from Cape Coral, Florida, recalls of his first outing on the V&H Yamaha. “At first, I rode it like a 250, but it’s real-

ly different. One you steer with the front and the other the rear. With the 250, you carry a lot of entrance speed; with the Superbike, it’s dial-a-slide.” Stevens put the OW to the test for the first time at Daytona 1990, where the team capitalized on the knowledge gained there during pre-season tire tests. Stevens set a new track record in qualifying to earn the pole position, and although mechanical problems hampered his race effort, the event was still a success, because the win went to his then-teammate, David Sadowski.

Part of the credit for the team’s early achievements should go to its use of on-board data-acquisition equipment, employed during testing from the very beginning. Wheel speeds, suspension travel, airbox pressure and engine rpm are monitored in the interest of obtaining maximum performance.

“The Yamaha worked really well at Daytona, and we left there thinking we had an advantage,” Stevens remembers. “But we were fooling ourselves, because the advantage we had there didn’t carry over to the other tracks. There were some improvements to be made.”

Problem number one was traction. “You couldn’t drive it off the corners,” Stevens says. “From 7500 rpm, it would just spin the tire.”

Much of 1990 was spent trying to get the motor’s claimed 150 horsepower to hook up. Most of the attention was lavished on the rear suspension; the team even made its own shock linkage with a more linear rising rate in an effort to improve sidegrip. The efforts almost paid off at the season-ending Willow Springs National, where Stevens looked like a sure winner until he chunked a tire just short of the finish.

“I learned a lot,” Stevens says of the season in which he finished fourth in the standings. His sentiments are echoed by Johnson: “The whole team was learning. Part of the year, we were our own worst enemies. It seemed like we were always fixing crash damage.” But it wasn’t the Superbikes they were fixing; it was the team’s FZR600 supersport bikes, which Stevens crashed no less than seven times in 1990, citing his incompatibility with the DOT-approved street tires mandated by the class rules.

Although the 1990 campaign was over, there was no rest for Vance & Hines. There were test sessions every 10 days throughout the off-season. It was during one of those tests, at Laguna Seca, that an experiment yielded valuable dividends. The entire bike was lowered in an effort to change the center of gravity, thus easing cornering transitions. The results took the team by surprise.

“We never expected it, but the bike started hooking up better and Thomas was able to go faster,” Johnson says. “That convinced me that we needed a full-time suspension program.”

Rather than reassigning someone from within the team, Johnson hired Dale Rathwell, a noted Canadian suspension expert, who joined the V&H team for the entire 1991 season.

“Having Dale on the team helped me a lot,” Stevens says. “He taught me a procedure for setting up suspension. We worked on making the bike easy to ride fast. The more comfortable I am with it, the faster I can go.”

“That’s probably the single most important thing we worked on over the winter,” Johnson adds. “We didn’t try to break lap records; we tried to make the bike go the same speed, easier.”

That philosophy carried over to the races, as well.

“We never worried about qualifying fast,” Stevens says. “We just concentrated on our race set-up.”

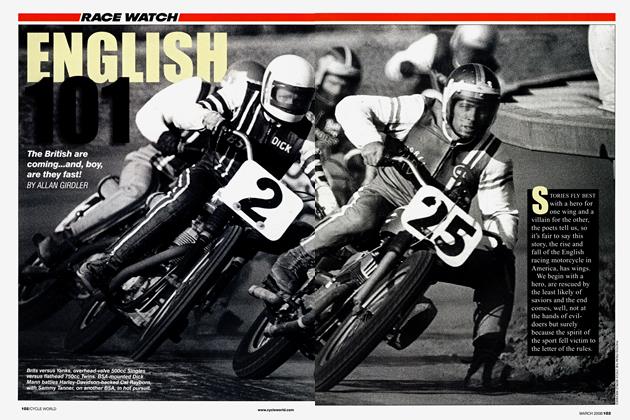

Daytona 1991 proved that the Vance & Hines Yamahas still had plenty of horsepower, as Stevens finished third after being nipped at the line by his new teammate, Jamie James. But the 1991 Match Races in England showed that there still was work to be done in the traction department. Limited practice on cold, wet, slippery tracks resulted in the American team getting trounced by what was essentially local talent.

“We came back from England with our tails between our asses,” Stevens says. “That’s when the real development started.”

This time, the focus was on the motor.

“I looked at the dyno charts, and could see where we weren’t making good power,” Leonard explains. “There was a 30-horsepower gain between 9000 and 9500 rpm. We made a conscious decision to give up peak horsepower in order to gain > some down low.”

That better spread of power was first tried at the Loudon National. “It was quite a change from what we were used to,” says Stevens. “The

engine actually felt slow.”

“But the lap times were there,” Leonard interjects.

The result was one of Stevens’ most impressive performances of the year. Though he qualified on the third row, he cut a swath through the pack to finish third. And he avenged his Daytona performance by passing James on the final lap.

Stevens’ title hopes gained momentum at Charlotte, North Carolina, where he took the series points lead when his teammate retired with tire troubles. And his one and only win> in the next round at Mid-Ohio further extended his advantage.

The next big jump came at Topeka, where the team tried a new exhaust pipe. Essentially a copy of the one used on the factory Yamaha YZF750 Stevens had raced in the Suzuka 8Hour, the pipe further broadened the spread of power. Unfortunately, carburetor-jetting problems resulted in them

abandoning it for the race, and Stevens finished a disappointing fourth.

Between Topeka and the next race at Texas World, the team tested for four days at Willow Springs, with most of that time spent matching carburetion to the new pipe. “I think I changed the jets 12 times in one day,” Leonard complains.

Leonard complains.

“It’s like a tractor now,” Stevens says as I prepare to return to the track for my second session on the bike. “You'll see.” Well, I wouldn’t exactly call this a “tractor,” I think to myself as I struggle to match throttle position with the correct amount of clutch slippage, the bike’s clutch emitting horrible, graunching noises. But once underway, the Yamaha is a lot easier to ride than its almost-two-stroke exhaust note would suggest. There’s good power as low as 7000 rpm, with a noticeable increase beginning at 9000 and carrying on to its 13,000rpm redline. But there’s no sudden rush of power, just a steadily flowing stream, with crisp carburetion right off the bottom. The only places the bike threatens to spin the tire are in off-camber Turns Four and Six. With the bike’s short gearing, I see 13,500 rpm going down the front straight in top gear before sitting up to brake for Turn One.

Contrasting with the bike’s unnerving Turn Eight performance is its composure in Turn Two. The Dunlop radial slicks stick in the 100mph sweeper like nothing I’ve sampled before. Throttling out of Two, the short chute to Turn Three disappears beneath the wheels at a pace that I would have thought possible only on a modified Open bike. The powerful Brembos allow me to push hard into banked Turn Three, their excellent lever feel encouraging trail-braking deep into the corner. The bike wags its tail a bit under heavy braking, but steering remains neutral and the bike feels every bit as light as the 360-pound Superbike weight limit would suggest. It’s an awesome ride.

I begin to feel comfortable on the OW at about the same time my riding session is over. I’m tempted to take a deep breath and try for one last quick lap-to see if I can do that l :30—but the thought sets off an alarm in the logical side of my brain; I’m here to write a story, not to audition for a race team. I’ll leave the 1:30s to Canet. Reluctantly, I return to the pits.

“One-thirty-three. Not bad," Stevens kindly informs me.

Thanks, Thomas, it was fun, but I think I’ll keep the day job. □

Clipboard

Stevens to Kawasaki, DuHamel to Europe

Well, it’s Silly Season time again, and the big news on this side of the Atlantic is that newly crowned AMA Superbike Champion Thomas Stevens will defend his title on a Muzzy Kawasaki, rather than a Vance & Hines Yamaha. “It was a business decision,” Stevens said the day he signed the contract, “Kawasaki can offer me things that Yamaha can’t.” Those things, according to Stevens, are rides in

select World Superbike rounds on competitive equipment-appearances that, Stevens hopes, will serve as a springboard to a GP career. Ironically, Stevens will be teamed with his arch-rival in the 1991 championship, Scott Russell. Vance & Hines does not plan to replace Stevens, and will concentrate its efforts on 1989 Superbike champ Jamie James, with Larry Schwarzbach remaining with the team for a second year.

Over in the Honda camp, Miguel DuHamel has turned down a sweet deal from Commonwealth Racing, and looks set to sign with Sonauto, the French Yamaha importer, to campaign a YZR in 500cc GPs. 1991 Commonwealth teammate Richard Arnaiz, meanwhile, is negotiating for his return to Europe, where he won the 1990 European Superbike Championship on a Team Rumi Honda. This time, however, he hopes to focus on the World Superbike> Series. Commonwealth had already signed privateer standout Tom Kipp to replace Arnaiz, and their search for a replacement for DuHamel netted them Mike Smith, who last year rode for Yoshimura Suzuki and in 1990 rode Team Hammer Suzukis to the WERA F-USA and Endurance Championships.

Smith’s departure-and the decision not to renew Tommy Lynch’s contract-left the door open at Yoshimura, where former Daytona 200 winner David Sadowski and Team Suzuki’s Britt Turkington, fresh from his wins in the WERA Endurance Championship and the 750cc Suzuki Cup Final, were slotted right in.

Two Brothers Racing, the other Honda team, will again field threetime world champ Freddie Spencer on an RC30 Super bike, with Canadian Steve Crevier as his teammate. Joining the duo will be Texan Rick Kirk, who’ll campaign a supersport CBR600F2 and an RS250. Spencer was rumored to be negotiating for a Fast By Ferracci Ducati ride, but his win at Miami gave Honda the incentive it needed to cough up some greenbacks; he will reportedly be the highest-paid rider in U.S. roadracing this year.

Having been turned down by Fast Fred, FBF signed French Canadian Pascal Picotte for the AMA Superbike Series. Doug Polen will remain with Ducati, though he'll concentrate on the World Superbike Series, which he says he’d like to win three consecutive times before retiring. He will, however, compete in the Daytona 200. And considering that during recent tire tests Polen turned lap times four seconds faster than the lap record he set during qualifying for last year’s 200, he has to be considered an early favorite.

But it’s too early to speculate. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

March 1992 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

March 1992 By Peter Egan -

Columns

ColumnsTdc

March 1992 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1992 -

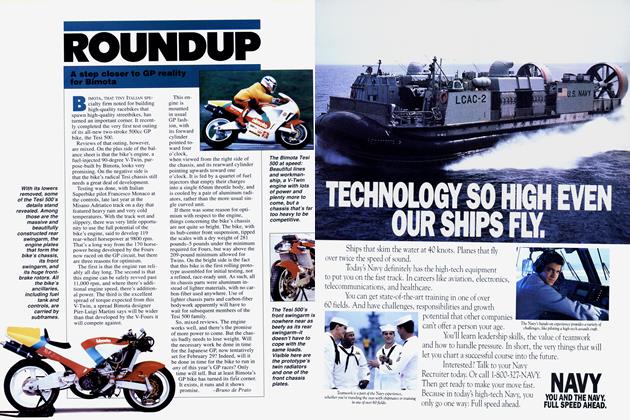

Roundup

RoundupA Step Closer To Gp Reality For Bimota

March 1992 By Bruno De Prato -

Roundup

RoundupAmerica 1: Gold-Plated Superbike

March 1992 By Jon F. Thompson