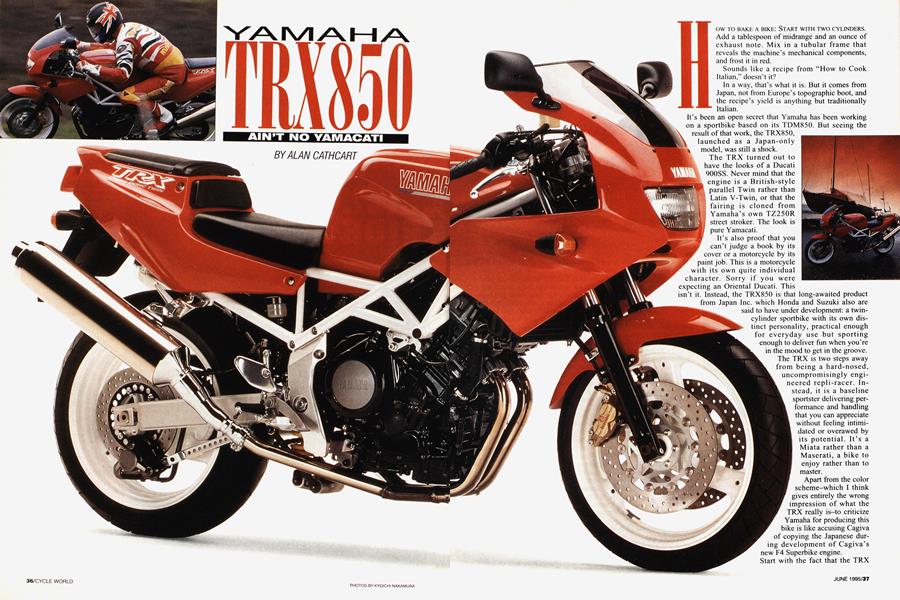

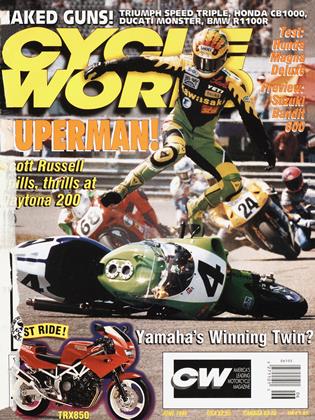

YAMAHA TRX850

AIN'T NO YAMACATI

ALAN CATHCART

HOW TO BAKE A BIKE: START WITH TWO CYLINDERS. Add a tablespoon of midrange and an ounce of exhaust note. Mix in a tubular frame that reveals the machine’s mechanical components, and frost it in red.

Sounds like a recipe from “How to Cook Italian,” doesn’t it?

In a way, that’s what it is. But it comes from Japan, not from Europe’s topographic boot, and the recipe’s yield is anything but traditionally Italian.

It’s been an open secret that Yamaha has been working on a sportbike based on its TDM850. But seeing the result of that work, the TRX850,

launched as a Japan-only model, was still a shock.

The TRX turned out to have the looks of a Ducati 900SS. Never mind that the engine is a British-style parallel Twin rather than Latin V-Twin, or that the fairing is cloned from Yamaha’s own TZ250R street stroker. The look is pure Yamacati.

pure

It’s also proof that you can’t judge a book by its cover or a motorcycle by its paint job. This is a motorcycle with its own quite individual character. Sorry if you were expecting an Oriental Ducati. This

isn’t it. Instead, the TRX850 is that long-awaited product from Japan Inc. which Honda and Suzuki also are said to have under development: a twincylinder sportbike with its own distinct personality, practical enough for everyday use but sporting enough to deliver fun when you’re in the mood to get in the groove. The TRX is two steps away from being a hard-nosed, uncompromisingly engineered repli-racer. Instead, it is a baseline sportster delivering performance and handling that you can appreciate without feeling intimidated or overawed by its potential. It’s a Miata rather than a Maserati, a bike to enjoy rather than to master.

Apart from the color scheme-which I think gives entirely the wrong impression of what the TRX really is-to criticize Yamaha for producing this bike is like accusing Cagiva of copying the Japanese during development of Cagiva’s new F4 Superbike engine.

Start with the fact that the TRX isn’t a V-Twin. This motorcycle fits squarely into Yamaha’s tradition as the Japanese manufacturer most closely wedded to the twincylinder, four-stroke theme. Though the innovative-but-flawed Vision 550 liquidcooled eight-valve is a model I’m sure company brass would rather forget about, the fact is that Yamaha has consistently hit the sports-Twin bullseye during the past quartercentury, with models as diverse as the XS650, the XS500, the XV920 V-Twin and more recently the Super Ténéré and TDM850. This company has a sporting-Twin heritage.

To create the TRX engine, Yamaha’s development team started with the dohc Twin from the TDM850. They retained the Genesis slant-block format, in which steeply inclined cylinders allow a healthy degree of downdraft for performance engine tuning, and they revamped the engine’s 360-degree crank to deliver the world’s first production parallel-Twin with a 270-degree crank throw. Since 360 minus 270 equals 90, the effect delivers the same offbeat lilt to the engine note, the same pulsing throb to the power delivery, and the same dose of grunty torque to the back wheel, as you get from a 90degree V-Twin without the obvious architectural downside that engine entails. Yamaha admits that feeling was at least as important as function in opting for the 270-degree layout. But in creating the first-ever Big Bang parallel-Twin, it’s actually copied the company’s own works Super Ténéré rally racer, ridden by Stephane Peterhansel to a Dakar rally victory yet again this year. This bike uses the 270degree format to enable it to match the off-road tractability of the Ducati 900 engine fitted to its Cagiva Elefant rival.

Compared to the TDM engine’s softer state of tune, the TRX has its compression ratio boosted to 10.5:1. It’s also got a bigger airbox, a peakier intake camshaft-the exhaust cam is unchanged-and flywheel mass reduced by 14 percent for quicker engine acceleration throughout the rev range. The 10-valve cylinder head uses the same valves as the TDM, and the twin balance shafts are retained to smooth out vibration without sacrificing character. The five-speed gearbox has a close-ratio gear cluster more suited to sporting use, while the dry-sump engine has a cast-alloy oil tank centrally located above the gearbox to compact overall mass and aid handling.

After first experimenting with flatslide carbs for crisper throttle response, Yamaha settled on a more sophisticated carburetor package, using twin 38mm Mikunis fitted with an electronic throttle-position sensor and accelerator pumps. The TPS is part of a three-dimensional mapped engine-management system, with a trio of sensors varying the ignition timing according to engine revs, carb-slide position and throttle operation. Delivering a claimed 83 horsepower at 7500 rpm, the TRX is 11 ponies more powerful than the TDM, and it offers 62.2 foot-pounds of torque.

The result of all this work is a distinctive personality that comes alive as soon as you nail the starter. Instead of the TDM’s flat rasp, the TRX has a trademark lilt to the engine note, but still sounds a little smoother and less lumpy than a desmo V-Twin-more like what I imagine the Harley VR1000 Superbike, with its 60-degree V-Twin,

would sound like in muffled street form.

The lack of a full fairing sends quite a lot of mechanical noise from the top half of the engine upwards. Though it’s liquid-cooled, the TRX sometimes sounds almost as tappety as a Moto Guzzi. But this adds to the bike’s character, underlined by the crisp, offbeat exhaust note from the twin silencers of the 2-into-l-into-2 exhaust system. The engine pulls cleanly from just off idle, with a little roughness until 3000 rpm, when it starts to smooth out. The power builds smoothly, but with an extra kick at 4500 rpm when it comes on its cams. There’s a really satisfying rush of extra power from there on up to the 8000-rpm redline. There’s only a slight drop off in power as the engine tops out. And while there isn’t the same ultrapunchy midrange throttle response you get from, say, a Ducati 900SS, and not quite so much torque, the Yamaha engine feels freerrevving and zippier. It’s a lovely power unit that doesn’t remind you

of any other ride.

The TRX’s gear ratios are well chosen and more evenly spaced than the TDM’s, with an 800-1000 rpm average gap between ratios, and fourth and top fairly close together. The gearchange is very crisp, too.

At the cost of the inevitable comparisons with Ducati, Yamaha went for a tubular-steel spaceframe. A more accurate reference point for the Yamaha chassis is, in fact, specialsbuilder Segale, whose distinctive composite chassis design the TRX follows. This design employs castaluminum swingarm pivots bolted to the back of the engine, with the spaceframe structure on top and the engine acting as a fully stressed member. Steering geometry uses 25-degrees of head angle and 3.9 inches of trail. The fork is a conventional 40mm item-an upside-down fork would have added cost, so that’s one aftermarket option potential owners may wish to pursue. Wheelbase is a fairly short 56.3 inches, and an extruded-alloy swingarm with rising-rate linkage and fully adjustable Öhlins shock holds up the rear end. The three-spoke wheels, sourced from the FZR600, wear Michelin Hi-Sport radiais in narrowish sizes: front is a 120/60, rear a 160/60. The twin 10.5-inch rotors, also sourced from the FZR600, are gripped by a pair of four-piston Brembo calipers. The claimed dry weight of this assemblage is 414 pounds.

Though designed for the Japanese market, the TRX’s riding position is surprisingly roomy—even taller riders will find enough space to be comfortable, and the handlebar position allows a riding position that is both more comfortable and less tiring than the racier riding position of many European sports Twins. The footpegs are well positioned, too, with room for your legs but enough ground clearance that they don’t touch down during spirited cornering.

At speed, the Yamaha feels light and easyhandling without being twitchy. It allows you to pick your line and hold it in a turn without undue effort. Changing direction from side to side in fast swervery is a snap: This may be an 850, but it feels like a 500 in terms of agility and steering response, probably because of the compact mass of the parallel-Twin engine. The suspension settings are presumably chosen for smooth Japanese highways, so are slightly undersprung for bumpy Euro-roads. Even as set up, the sus-

pension handled freeway joints and other ridges in the road quite well. The front end dives a fair bit under heavy braking, so more spring is needed, but in spite of the smallish front discs, the TRX stops really well without your having to squeeze too hard on the lever. Getting hard on the power coming out of a turn will see the rear Michelin hooked up

well once it’s warm, thanks to the nicely progressive suspension linkage that also delivers good ride quality. The TRX doesn’t understecr under power, hugging the chosen line hard on the gas. And as I found out fiddling around in a Dutch fishing village, the steering lock is enormous-much better than you’d expect from a sportbike like this.

So the obvious question is this one: Is there a market for this motorcycle outside Japan, provided that the price can be as contained? I think there is. The TRX has bags of personality, is practical, fun to ride, and has heaps of real-world performance coupled with nimble handling and excellent brakes.

As for the color scheme-well, remember that Yamaha’s traditional corporate colors are red and white. Customers in Japan can have a red frame with white bodywork, if they prefer. But even with detail alterations needed to the suspension to make it more export-friendly, I’m sure there’s a market for the TRX.

It’s worth underlining that the TRX is a model developed specifically for Yamaha’s domestic market. Overseas subsidiaries may or may not opt to import it-1996 would be the earliest they could do so.

Yamaha Europe in particular is still undecided about whether or not there’s a viable market for the bike in Europe.

Would importing to Europe be the equivalent of carrying coals to Newcastle? A look at the sticker price in Japan may provide an answer:

The bike’s 850,000-yen price-a thousand yen per cc and about $8500 at current exchange rates-seems reasonable enough. What the price would be outside Japan, however, remains to be seen.

Only when you ride the TRX will you fully appreciate how different and individual a bike it is. Let’s hope Yamaha, in its corporate wisdom, sends the bike world-wide and allows us all a chance to take a few demo rides.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontDoin' the Wave

June 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsDucks Unlimited

June 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCAlloy Connection

June 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupBandits Coming Soon To Your Neighborhood

June 1995 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha's Surprise Single

June 1995 By Robert Hough