The portraiture of Ivan Nikolaevich Kramskoy

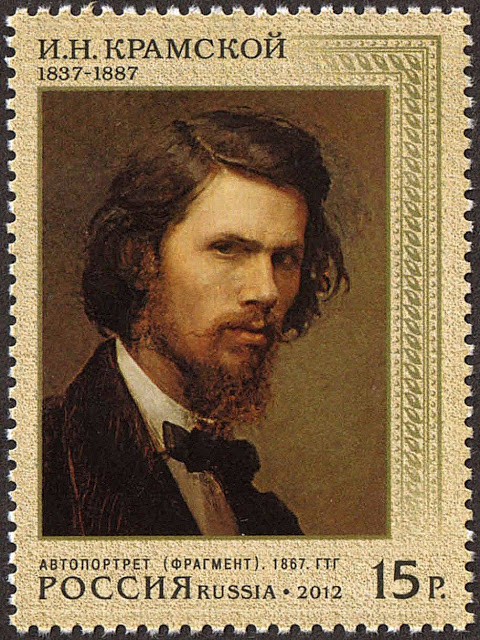

My third look at portraiture exhibited at the Tretyakov Gallery features the work of Ivan Nikolaevich Kramskoy, the artist who was born into an impoverished lower middle social class family on June 8th 1837 in the village of Novaya Sotnya, near Ostrogozhsk, a town in south-west Russia. He was the third son of a town council clerk of the municipal duma. He attended the local school but, at the age of twelve, when is father died, he was unable to continue his education. During these early years Ivan showed a great interest in and a talent for drawing but lacked the support of family and friends to follow his dream of becoming an artist. Help finally came his way when he was employed by a visiting photographer who employed him to work as a colour correction artist. In October 1853, aged sixteen, Ivan left his native village and after much travelling arrived in St Petersburg.

Having already worked for a photographer back home he found a job with a well-known St Petersburg photographer, Andrey Denier. Ivan gained many friends whilst living in the city and many were amazed at the quality of his artwork and persuaded him to study art. In the Autumn of 1857, aged twenty, Ivan Kramskoy enrolled at the St Petersburg Academy of Arts.

The St Petersburg Academy had, like most European Academies of art, a fixed way of teaching and pushed the long-established practice of depictions focusing on the Neoclassical tradition, as suitable subjects. However, many of the young aspiring painters were not interested in old fashioned historical and mythological subjects preferring to dwell on works of art, the depictions of which embraced social realism. The students were also critical of the social environment that caused the conditions which were depicted in their social realism paintings. It came to a head in 1863 when fourteen young artists, all studying at the St. Petersburg Academy of Art, rebelled against the choice of topic for the annual Gold Medal competition, “The Entrance of Odin into Valhalla”. Instead, the fourteen wanted to depict in their paintings the reality of contemporary Russian life, a Realist style similar to what had emerged in the art world in 19th century Europe and in protest, had refused to take part in the competition. The rebel students asked to be allowed to choose their own subjects but the Academy Council turned down their request, and so they left the Academy. It was such a sensitive issue with political connotations that the rebel artists were put under secret surveillance and the press was forbidden to mention them.

Ivan Kramskoi, who had already spent six years at the Academy, led this “group of fourteen” rebels. The protest was not just about what they had to paint but in the unjust conservatism of Russian society and the desire for democratic reforms which he believed could be furthered if artists developed a political responsibility through their art. His views were anathema to the Academy hierarchy and he soon became a figurehead for an increasing number of disillusioned artists who believed in his artistic and political philosophy.

The revolt of the fourteen, as it was termed, led to the formation of the Artel of Artists which was a cooperative association (artel). It was formed and organised by the art students who had been expelled from the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts. because of the “revolt of fourteen”. Ivan Kramskoy and four other artists set up home and a workshop in an apartment in the apartment house of Gudkov on Vasilievsky Island. It was here that they formed a kind of commune with the common workshop. Almost every evening young people gathered in Kramskoi’s apartment.

In 1870, seven years after the establishment of the Artel for Artists, the group under the leadership of Kramskoy formed the Peredvizhniki (Передви́жники, mobile workers), often called The Wanderers or The Itinerants. This group of Russian realist artists formed an artists’ cooperative in protest of academic restrictions. They formulated plans to hold a series of “Itinerant Art Exhibitions” in provincial locations which could be funded without State assistance allowing them to choose what was being exhibited without State interference. It was also a chance for them to preach political reform. They decided that the subject of their paintings should showcase the achievements of Russian art to the common man and woman. They hoped to foster public understanding of art and at the same time develop new markets for the artists. The first of Peredvizhniki’s “Itinerant Art Exhibitions” was held in 1871, in Nizhny Novgorod and from then on, the group organized a series of shows across Russia. Running besides the exhibition of their paintings were artists’ lectures and talks on social and political reform.

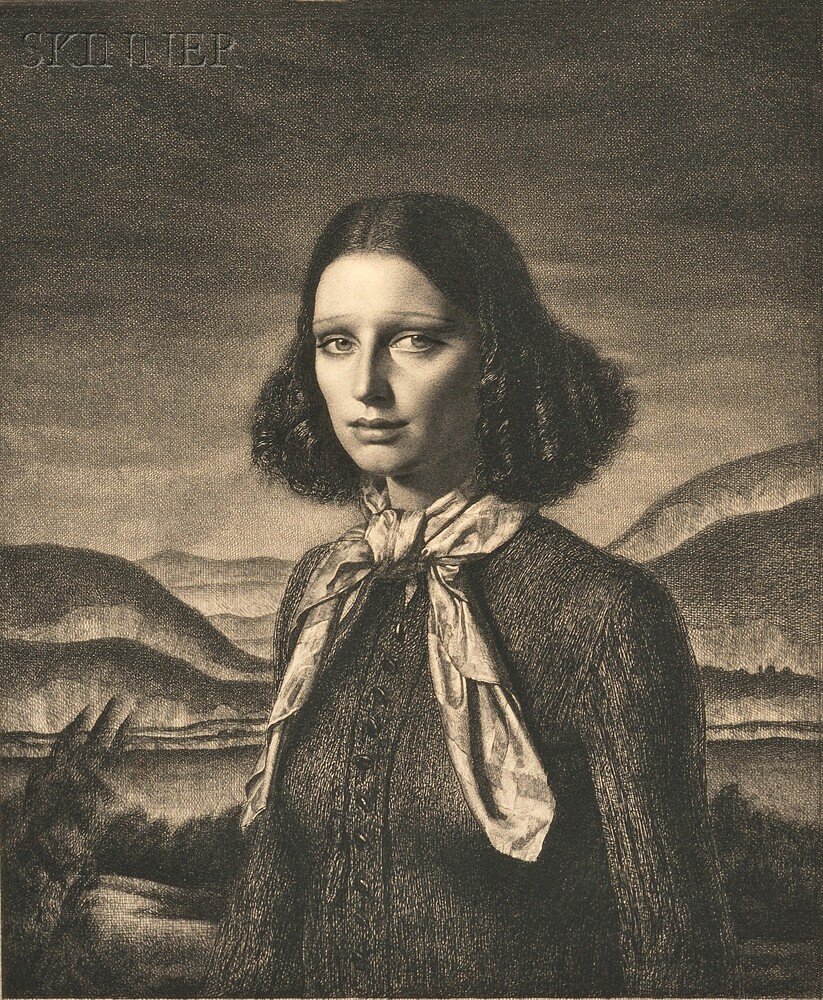

Surprisingly, the St Petersburg Academy initially welcomed the Peredvizhniki and even allowed them to host their first exhibition 0n November 29th, 1871. In all there were forty-seven paintings exhibited which received favourable reviews from the art critics. Ten of the paintings were portraits establishing the role of portraiture within the group. Kramskoi put forward three portraits of fellow artists, one of which was a monochromatic one depicting Fedor Vasilev. Vasilev was a Russian landscape painter who brought to the Russian art scene the term “lyrical landscape”. Lyrical landscapes were those which exhibit a certain spiritual or emotional quality. It could be that the depiction is of a sensitive and expressive nature. It could also be that the landscape, as well as depicting a picturesque view, conveys a particularly reflective, ardent or tender feeling, conceivably associated with romanticism. Vasilev was one of the twenty founder members of the Peredvizhniki Association in 1870. In 1871, aged just twenty-one, he was diagnosed with tuberculosis and so left St. Petersburg and travelled to Crimea, where he had hoped to find a cure for his illness. The plight of Fedor Vasilev touched the heart of many of his friends and contemporary artists. Kramskoy regularly contacted his friends asking them to help the ailing artist. The Society for Promotion of Artists sponsored his stay in the Crimea, but to meet his living costs he had to sell his paintings. He died in Yalta on October 6th, 1873 at the age of 23. A posthumous exhibition was held in Saint Petersburg and was an outstanding success with all his paintings being sold prior to the start of exhibition. Kramskoy’s portrait of Vassily avoided a mawkish depiction of a dying young man. Instead he depicts the young artist as a dapper young professional with an aura of dignity and professionalism wearing his attractively tailored three-piece suit and fob watch. Feodor Vassily reputation as a “boy genius” was well founded.

My next offering, in a way, is not actually a portrait, per se, but it is one of my favourite paintings by Kramskoy which hangs in the Tretyakov Gallery. It is entitled Christ in the Wilderness and was completed in 1872. It was first shown in 1872 at the Peredvizhniki exhibitions in St. Petersburg and later in many cities throughout the country. The haunting depiction is radical and, some may say, shocking. Kramskoy offers us an image of Christ that is very different from the usual sterile submissions of the past. In his depiction of the temptation of Jesus we can see his unbending realism. Jesus is seated on a boulder in a barren and dry wilderness. He is hunched over and has a dishevelled appearance. It depicts Christ sitting in a state of profound dejection and indecision, hands clasped due to tension not prayer. We see the suffering of Jesus as he endures life in the barren arid wilderness. He has his back to the rising sun as he sits hunched forward on a boulder. Mentally he looks anxious. Maybe he is contemplating the forty-day exile and whether he should or is able to continue despite all the temptations. Physically, he looks dishevelled. He looks tired and his face is gaunt and there can be no doubt that he is suffering. We can empathize with his hunger and thirst and through Kramskoy’s realist depiction we are able to sense Jesus’ loneliness during this period of haunting isolation. Leo Tolstoy described it as the best Christ he had ever seen.

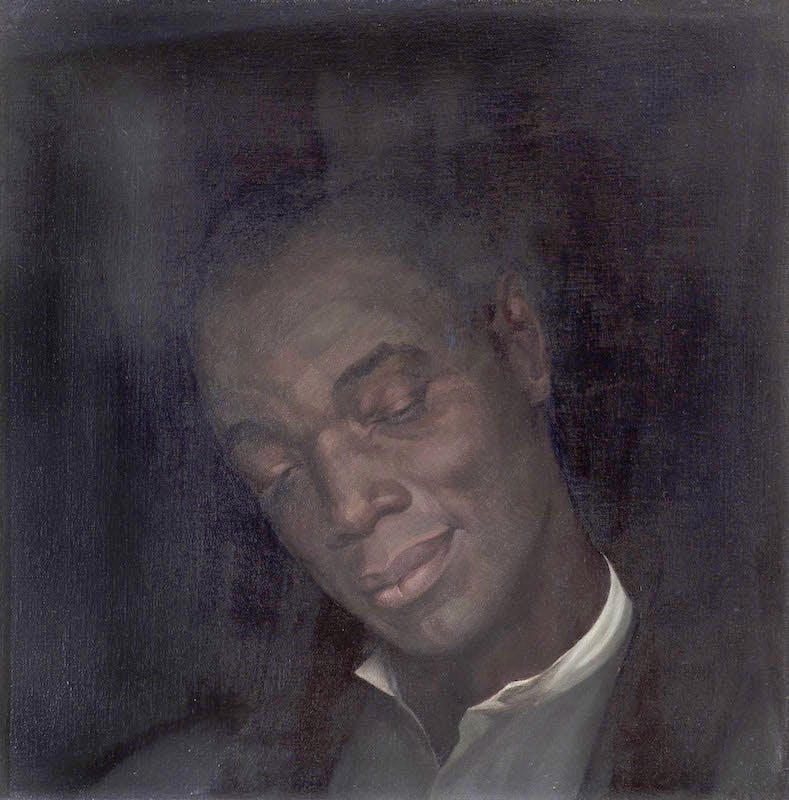

The plays of William Shakespeare were very popular in Russia in the nineteenth-century with the first edition of the Complete Works of William Shakespeare being published in the 1860’s. The Russian actor who was most famous for his portrayal of the Shakespearean characters was Alexander Lensky who often appeared on the stage of the Maly Theatre in Moscow which had opened in 1806. The theatre would often not appoint a director for the plays giving the position to one of the main actors. Lensky would often assume the role of main actor and director. Kramskoy and Lensky became good friends and in 1883 the artist gave the actor some painting lessons. Maybe it was the number of hours spent teaching Lensky that gave Kramskoy the chance to study him at close quarters. In his portrait entitled The Actor Alexander Lensky as Petruchio in Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew we see the actor in the costume of Petruchio, with his leather gauntlet, heavy jewelled chain and white ruff, so arranged to form tiers of differing textures. Against this, we have the tousled hair and downcast eyes of the actor who is immersing himself in his theatrical role.

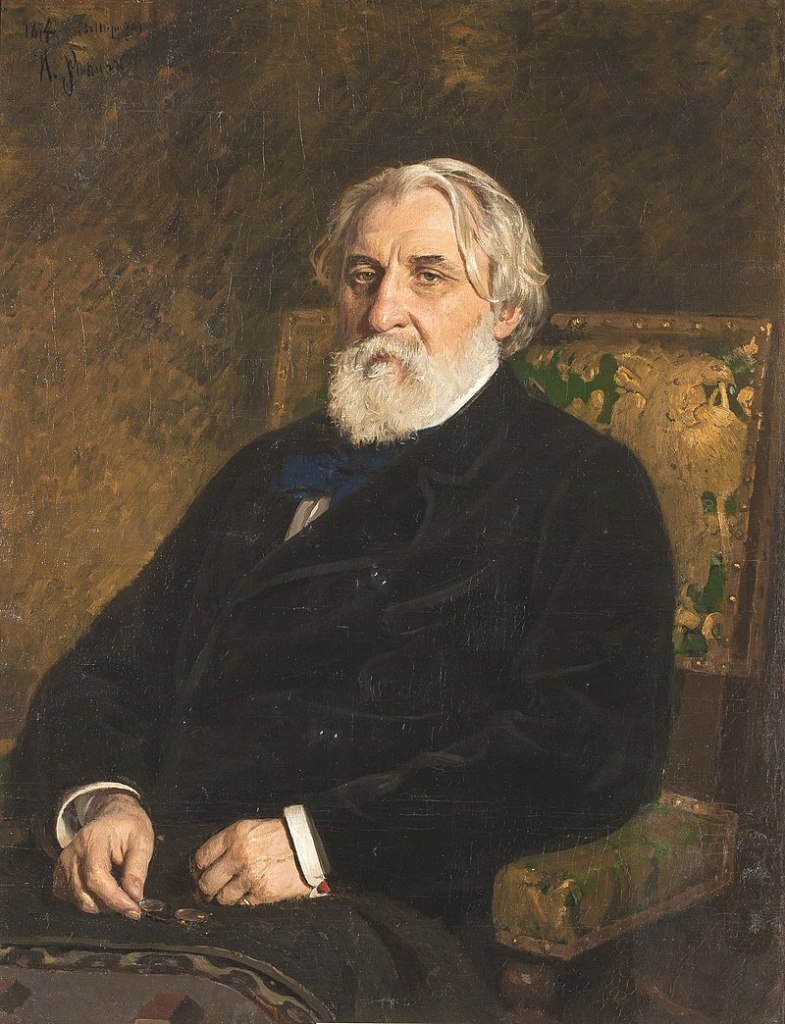

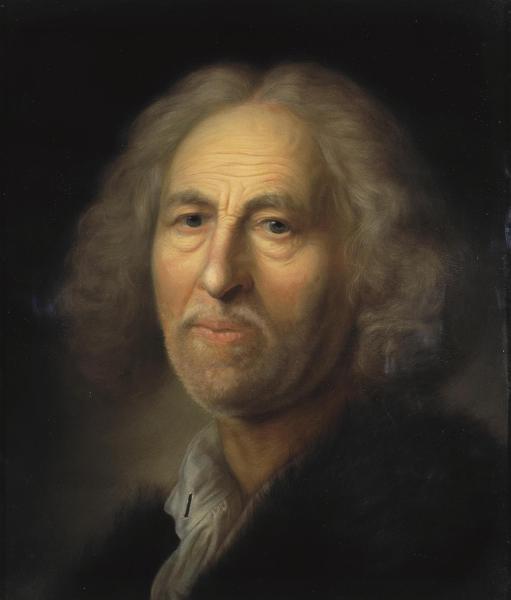

Fourteen years before Pavel Tretyakov commissioned Ilya Repin to paint portraits of Leo Tolstoy, he had approached Ivan Kramskoy with the same task once he realised that Kramskoy lived near Leo Tolstoy. Whether Tretyakov told Kramskoy that he had approached Tolstoy requesting him to be a sitter for a portrait on several occasions only to be refused, we will never know, but he did add that Kramskoy should use all his charm to persuade Tolstoy to acquiesce. Tolstoy did agree and artist and writer ended up becoming great friends. Tolstoy was working on his novel Anna Karenina at the same time Kramskoi was at the writer’s home painting his portrait. It is believed that Tolstoy ended up creating the character of Mikhailov, a Russian artist who paints Anna’s portrait in his book, and was based on Kramskoi’s personality. Kramskoy’s portrait is a dark and sombre depiction of the great man but one which Tretyakov liked and paid Kramskoy 5oo roubles for it in 1874.

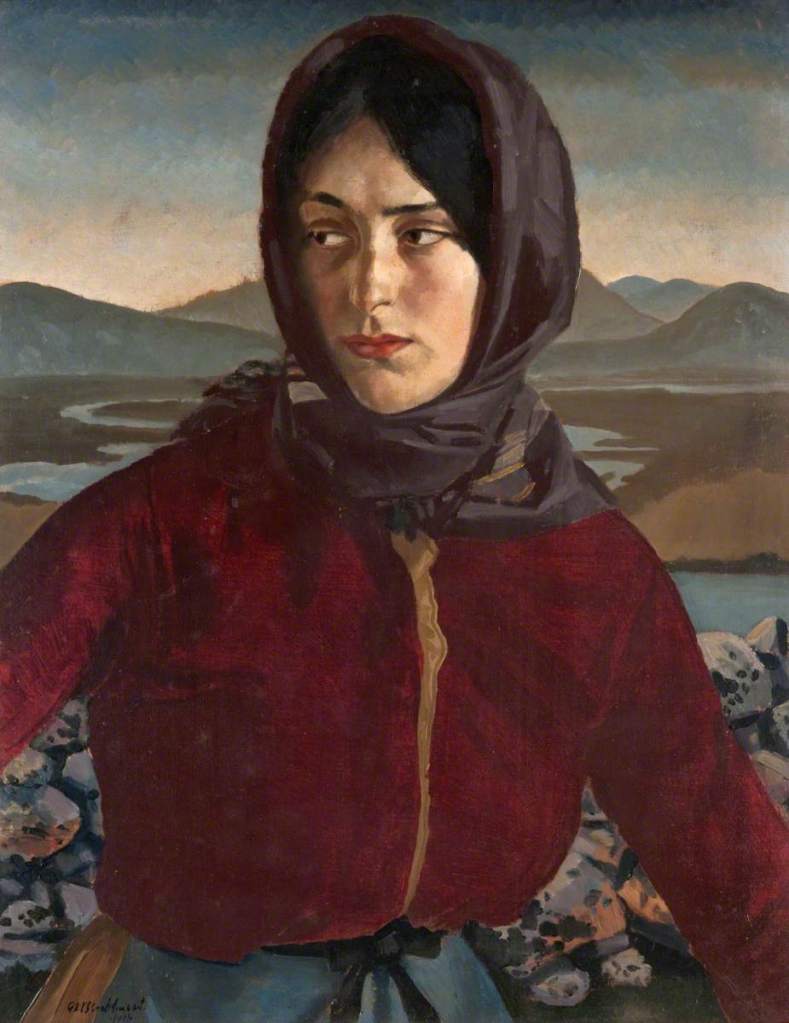

The final portrait by Kramskoy, belonging to the Tretyakov Gallery, which I am going to show you, is one surrounded in mystery as to who is the beautiful sitter for the painting. The unknown female is seen leaning back on the leather seat. She is exquisitely and sophisticatedly dressed. She wears a dark blue velvet fur coat which is trimmed with silver fur and decorated with satin ribbons. She has an elegant hairstyle which is almost hidden by a stylish hat with a white ostrich feather. Her right hand is concealed inside a furry clutch whilst the other hand can be seen covered by a dark kid glove. On her wrist we can see her lustrous gold bracelet. This majestic beauty is composed and looks down upon us with a somewhat haughty expression. She is very aware of the power her beauty commands. The architectural landscape in the background occupies an important place in the painting, with its pink/brown colouring. It is the blurry outlines of the Anichkov Palace that we glimpse as it emerges out of the fog.

The 1883 work by Kramskoy is simply entitled Unknown. In all the papers and notes left by Kramskoy nothing sheds light as to the identity of the beautiful woman. The Kramskoy portrait appeared at the eleventh exhibition of the Peredvizhniki’s Association Itinerant Art Exhibitions in November 1883. Viewers were mystified by who the model was for this work. Speculation came fast and furiously that it could have been a member of minor royalty or an actress but Kramskoy would not reveal the model’s name. Could she just be Kramskoy’s idea of the fictional heroine in Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina or Dostoevsky’s female character Nastasya Filippovna, in his novel Idiot. Another possible answer to the identity of the woman comes from a book written by Ilya Repin. In 1916 Repin worked on his book of reminiscences entitled Far and Near, with the assistance of Korney Chukovsky and in the book Repin tells of an incident which occurred in the workshop of the Artel of Artists group. He wrote:

“…One morning, on Sunday, I came to Kramskoy … From a troika-sleigh that arrived, a group of artel artists-artists with cold frost on fur coats fell into the house with a beautiful woman. I was just dumbfounded by this wondrous face, the height and all proportions of the black-eyed… In the general turmoil, chairs quickly boomed, easels moved, and the general hall quickly turned into a study class. They set the beauty on an elevation … I began to stare at the back of the artists … Finally, I got to Kramskoy. Here it is! That’s her! He was not afraid of the correct proportion of eyes with a face, she has small eyes, Tatar, but how many shine! And the end of the nose with nostrils is wider between the eyes, just like hers, and what a beauty! All this warmth, charm came only from him…”.

Dis Kramskoy remember that incident and make the lady the subject of his Unknown painting ? We will never know.

Ivan Kramskoy died at work 0n April 6th 1887 in St. Petersburg while standing at his easel. He was painting the Portrait of Doctor Rauchfus, which remained unfinished. He was forty-nine years of age.

In my final blog regarding the Tretyakov Gallery’s paintings I will talk about my favourite works housed by the Moscow institution, other than the portraits which I have looked at in the previous blogs.

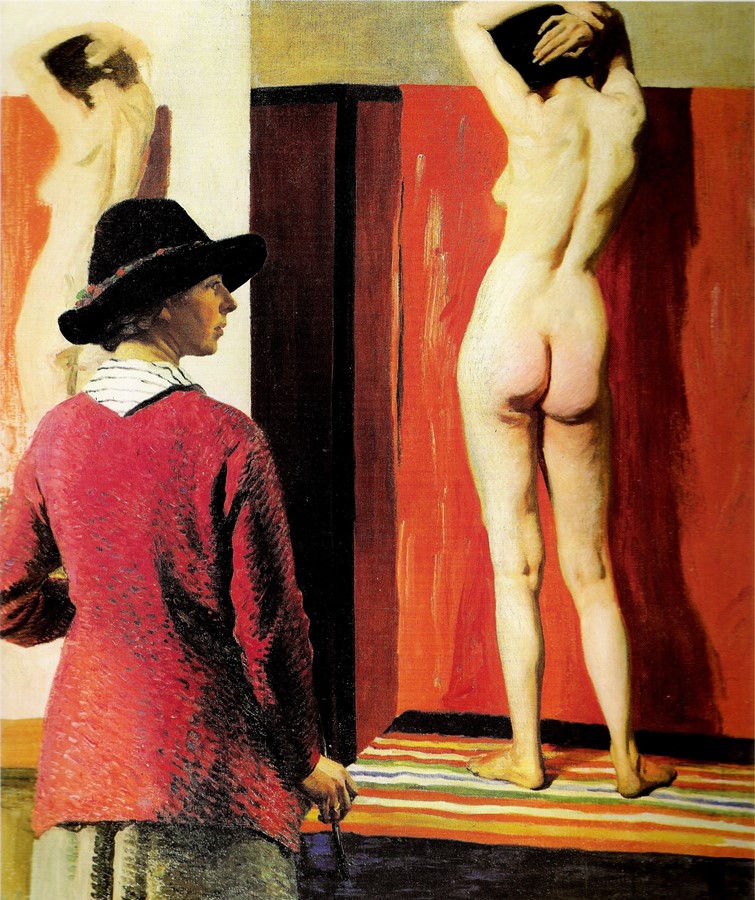

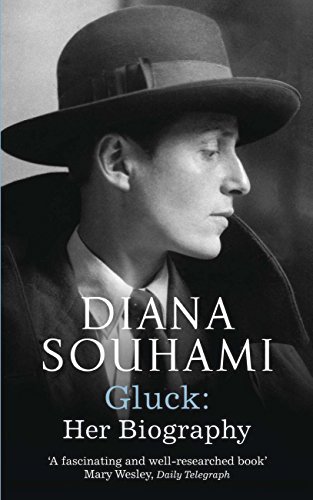

Most of the information for this blog came from the excellent book – Gluck: Her biography by Diana Souhami.

Most of the information for this blog came from the excellent book – Gluck: Her biography by Diana Souhami.