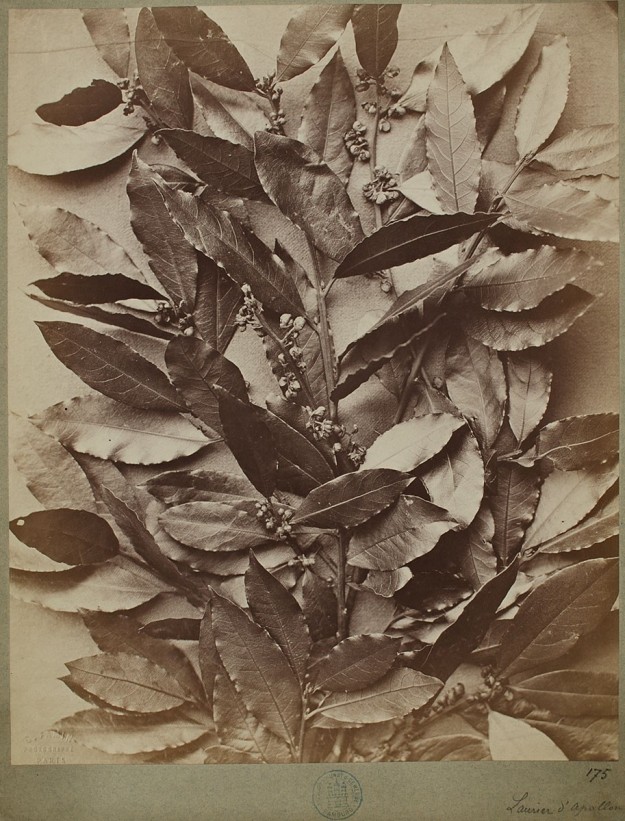

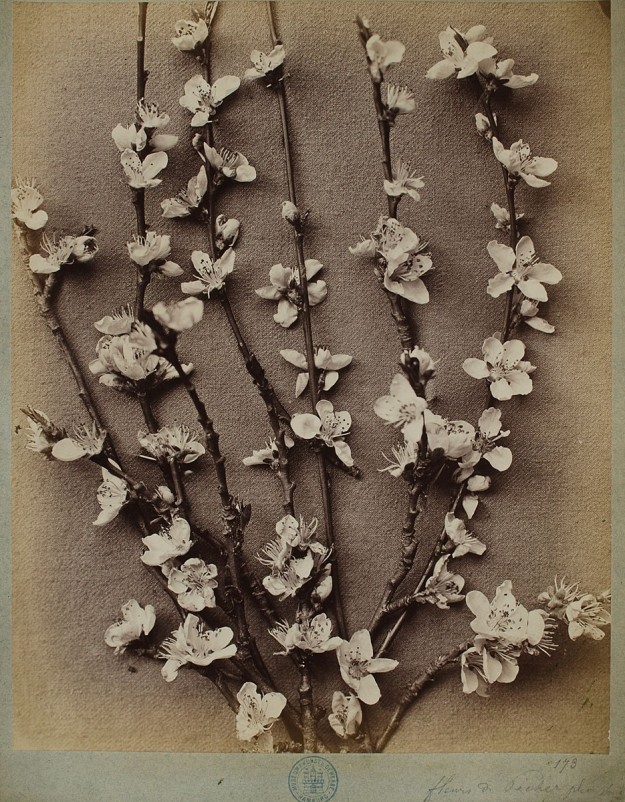

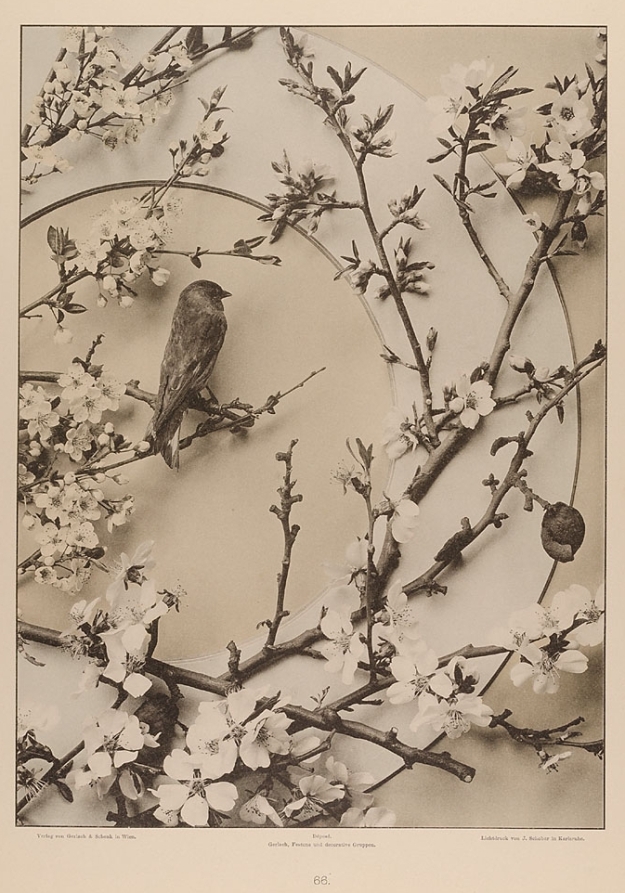

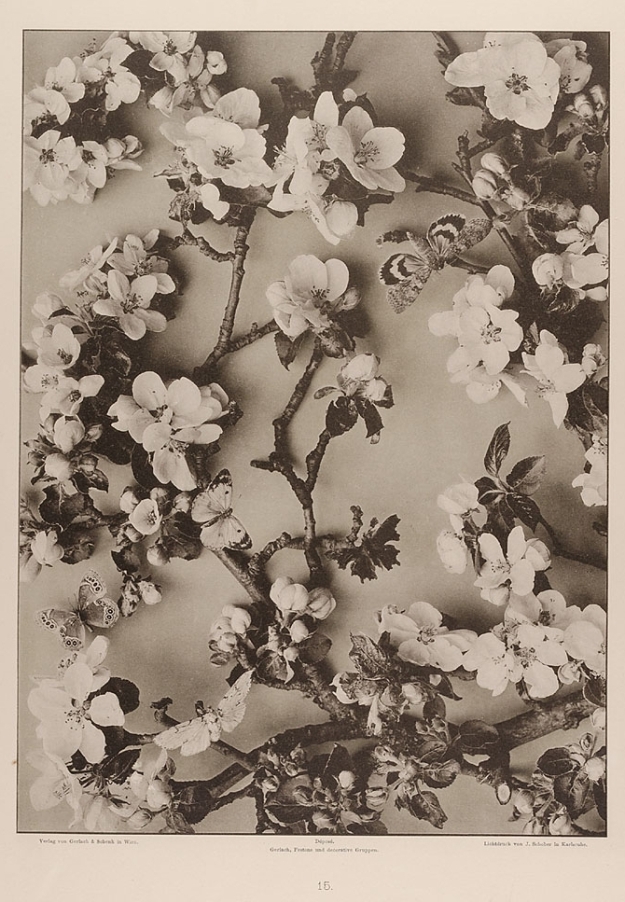

Apple blossom in the orchard at Fenton House, Hampstead

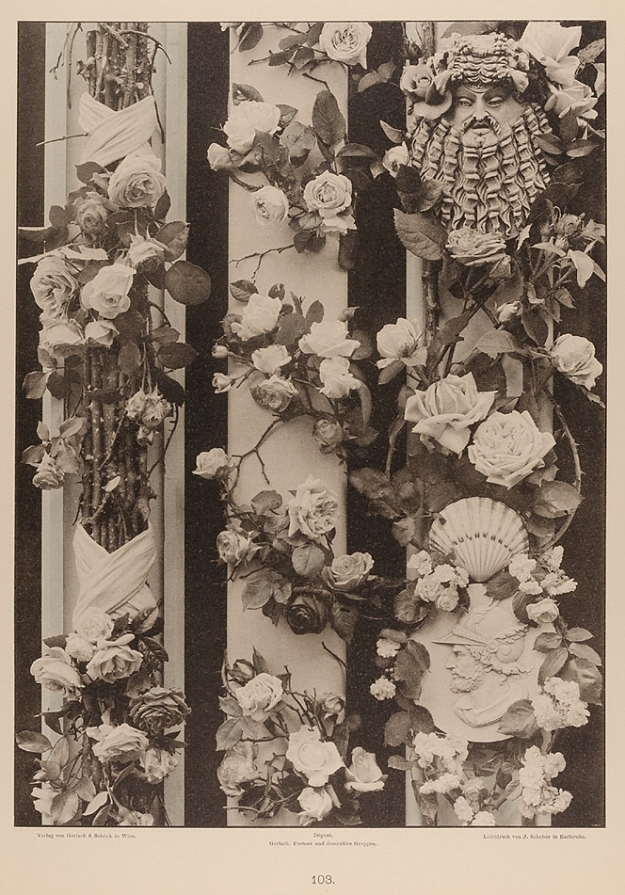

Standing in the orchard at Fenton House amongst the apple trees, now covered in blossom, is to experience something close to spring in the English countryside. Mown pathways edged with rustic bent hazel rods invite visitors to wander beneath the canopy of the trees, through meadow grasses and bulbs, surrounded by flowers. Yet, this peaceful place is not at the end of a quiet country lane, but in Hampstead, north London.

Located just a short distance away from the clamour and bustle of Hampstead High Street, Fenton House is reached through a series of winding residential streets. Dictated by the topography of this hilly part of north London, the gardens are laid out on various levels, cleverly connected by steps and pathways, the site bounded on all sides by mellow brick walls. These walls, together with tall, tightly clipped yew hedges divide the garden into distinct areas, each with its own special character. Some are wide and spacious; others smaller and more intimate, but all with a sense of surprise and discovery around each corner.

Fenton House is a rare survivor from a network of similar mansions constructed in this part of Hampstead in the mid 17th century for wealthy merchants whose business interests required them to live close to London. It’s thought Fenton House was built in the late 17th century and had a succession of owners before it was purchased in 1793 by Philip Fenton, a trader in the Baltic states, and from whose family the house eventually took its name. The house was inherited by James Fenton, who became an active campaigner against the development of Hampstead Heath in the 19th century.

In the early 20th century, the house came into the possession of Lady Katherine Binning and in 1952 the house and garden were gifted to the National Trust. An avid collector, the house now serves as a museum for her collections of ceramics and needlework, and also houses the Benton Fletcher collection of musical instruments which was gifted the the National Trust in 1937.

At Fenton House the style of planting is not fixed to a certain point in the site’s history, and the gardeners enjoy some freedom to develop their own ideas. Retaining certain characteristics from the 1930s when it was still a family garden, albeit a rather grand one, the formal lawn is closest to the house and was once used as a tennis court. Beyond this is the rose garden and a series of formal flower borders, enclosed by box hedges.

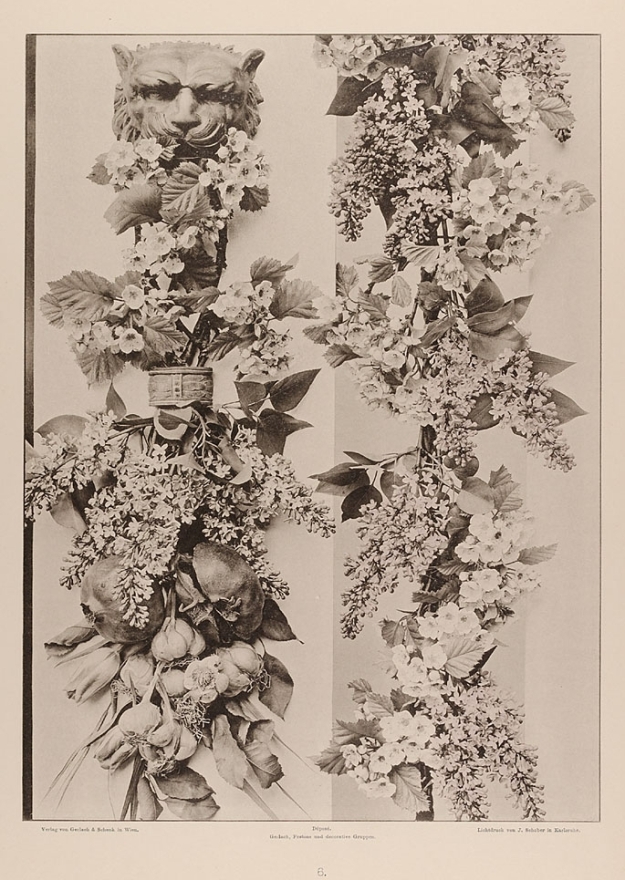

Echoes of the 18th century are represented by yew hedges and topiary, forming a perfect backdrop for the painted figure of a young man, and for period garden seats, placed at intervals around the garden for visitors to enjoy its quiet corners.

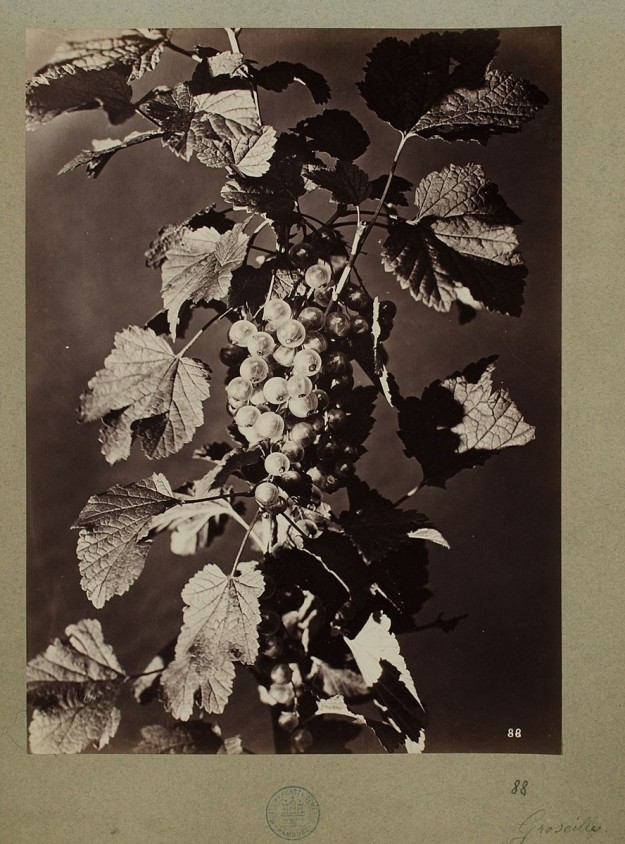

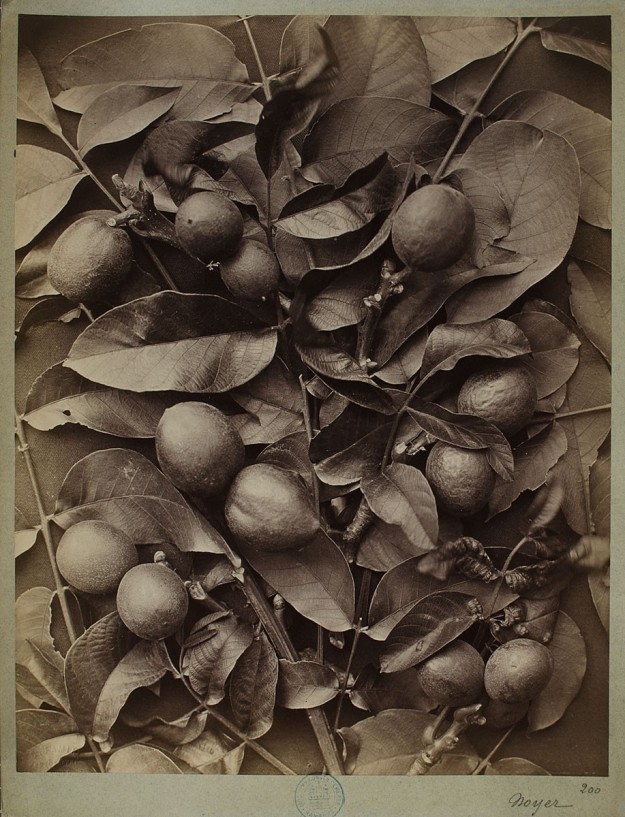

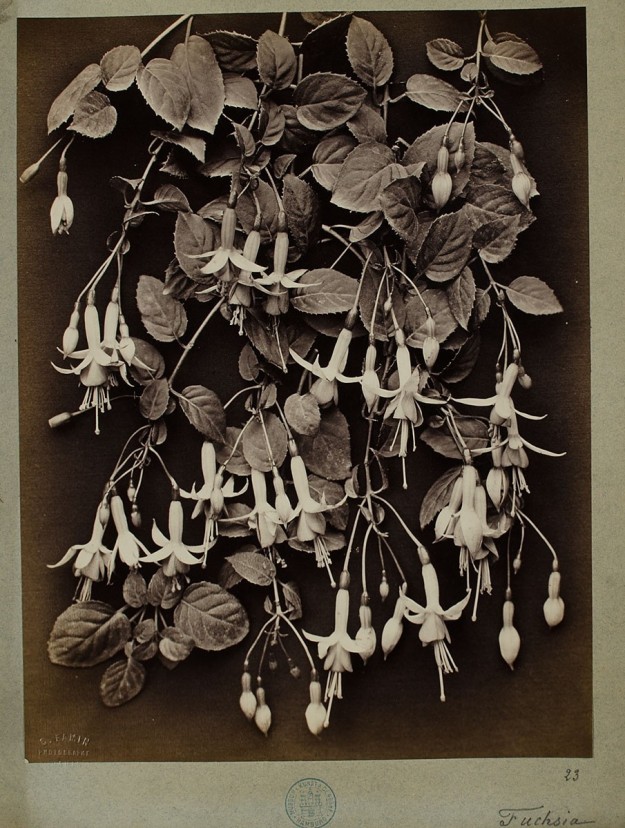

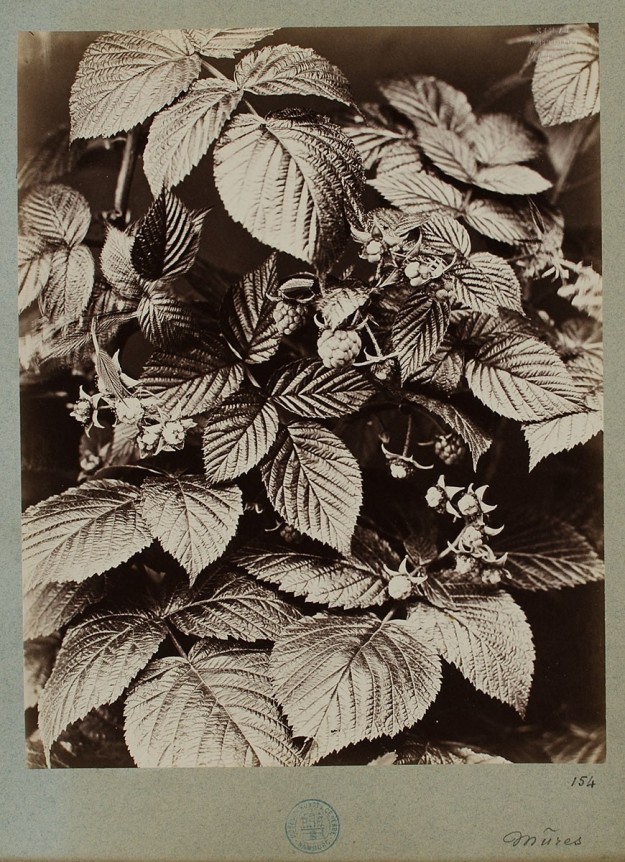

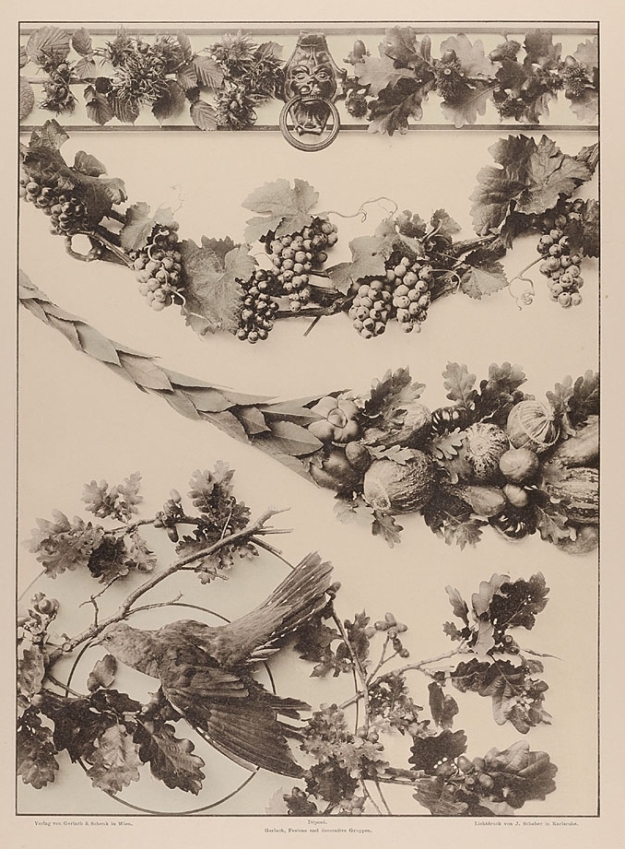

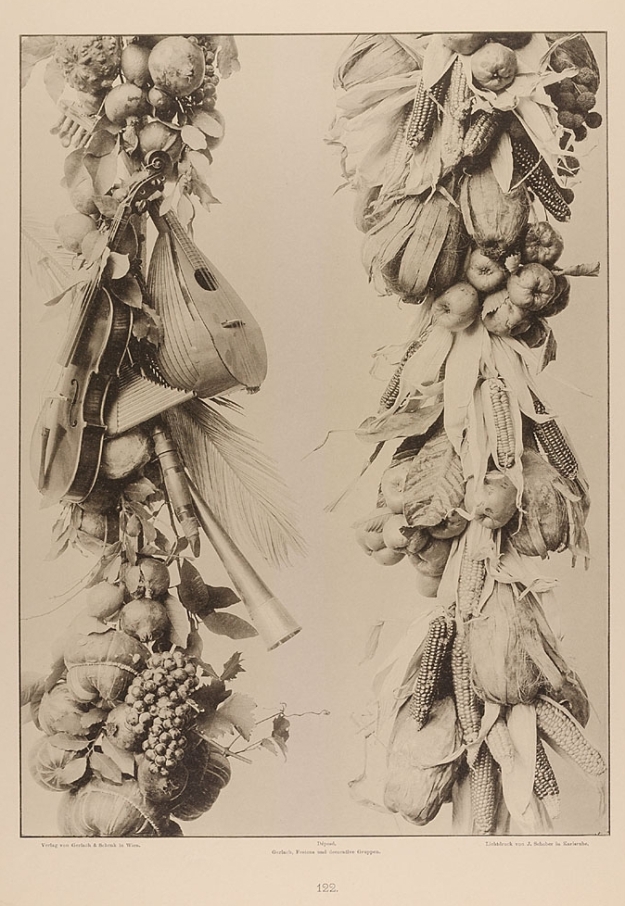

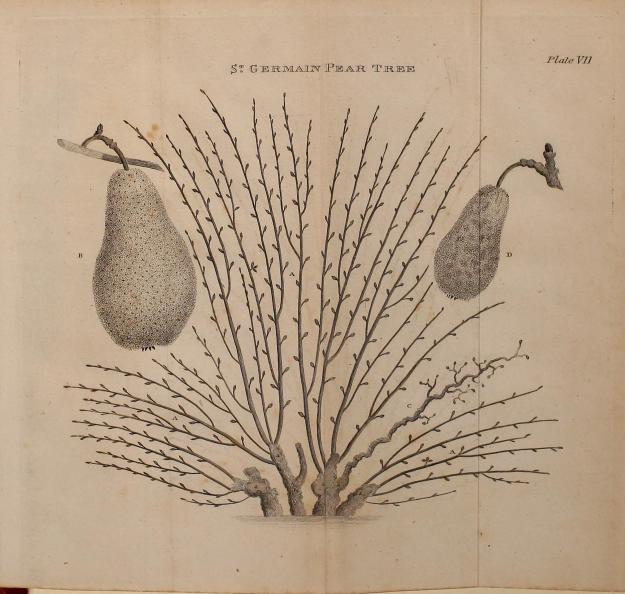

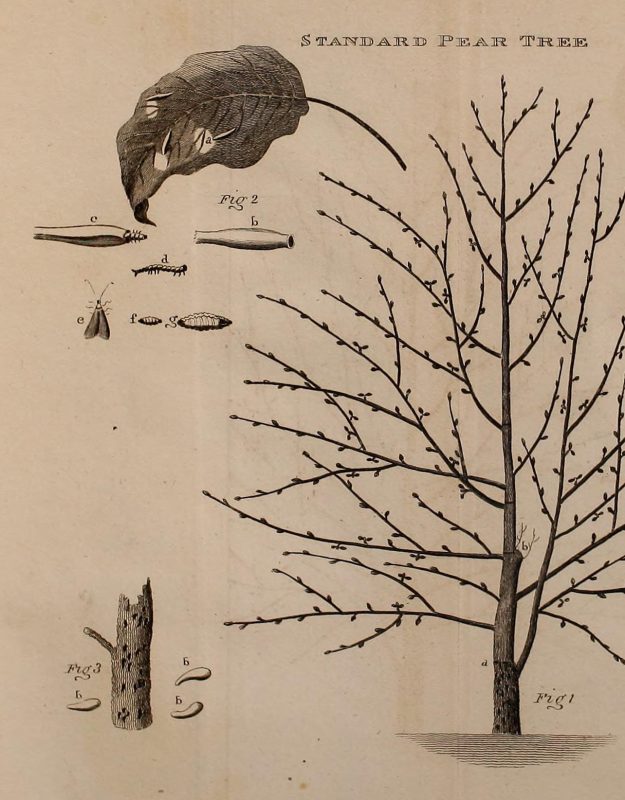

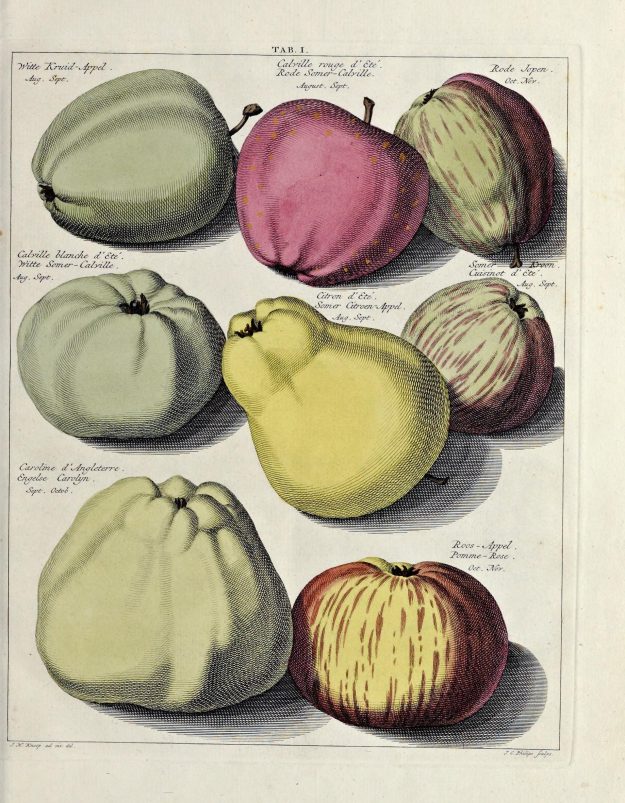

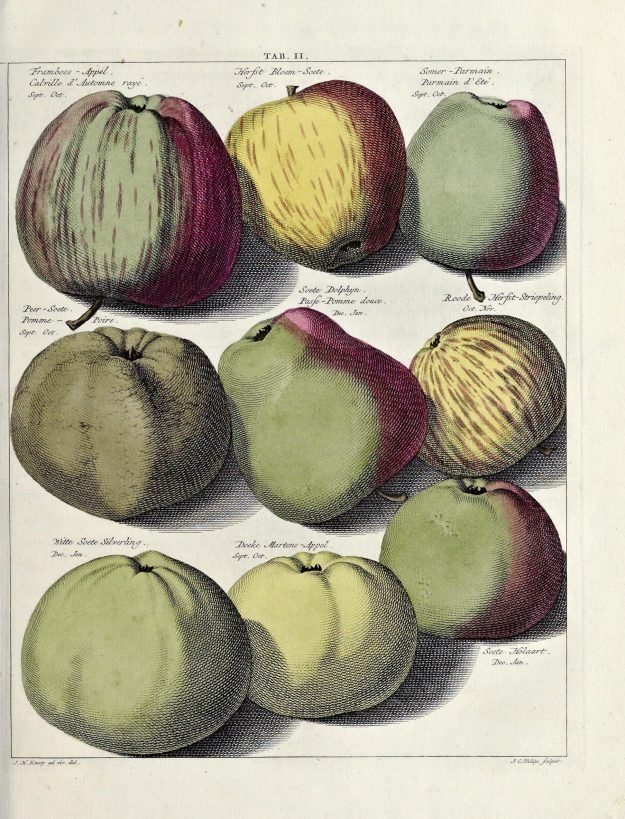

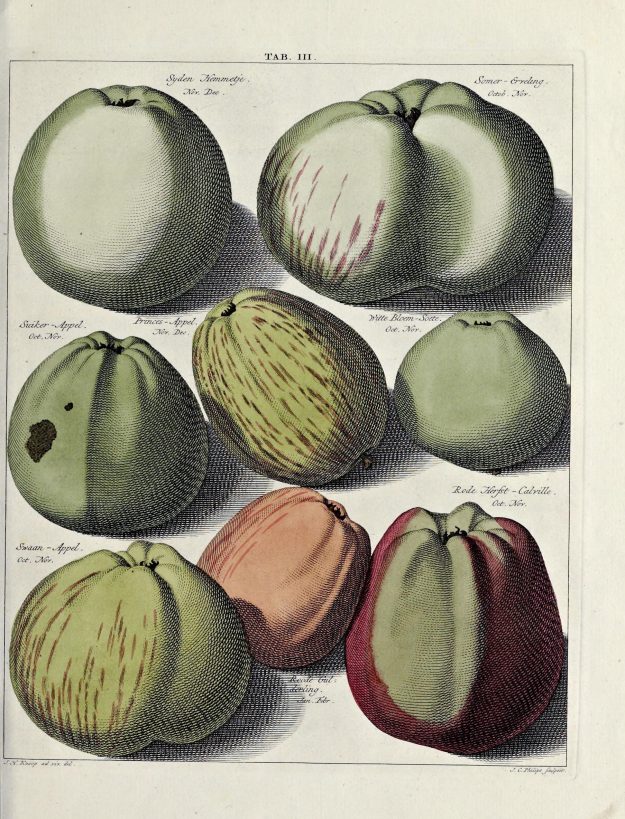

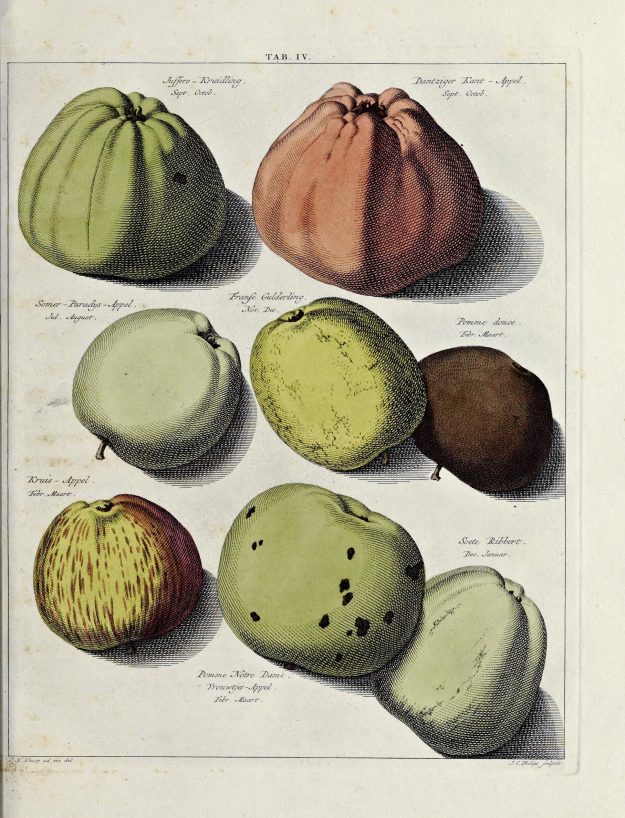

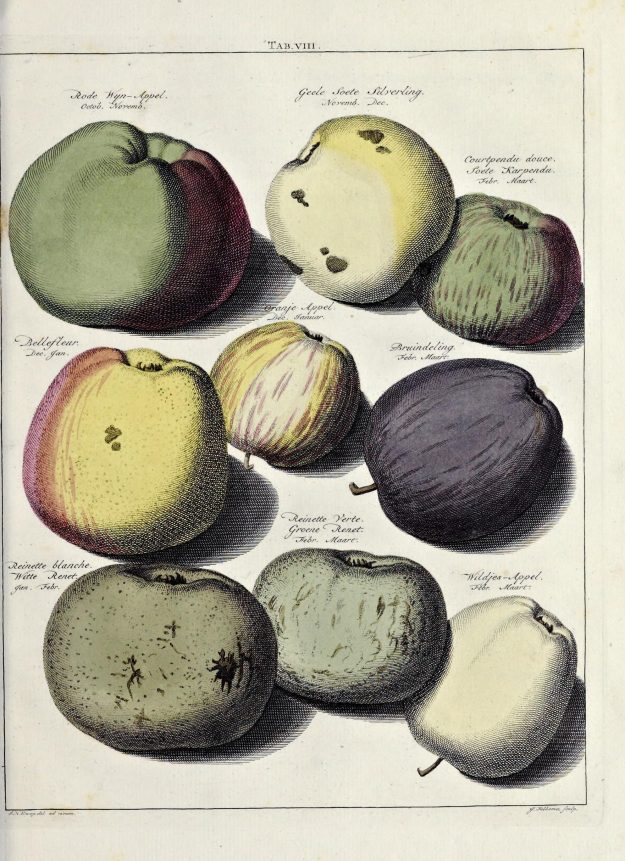

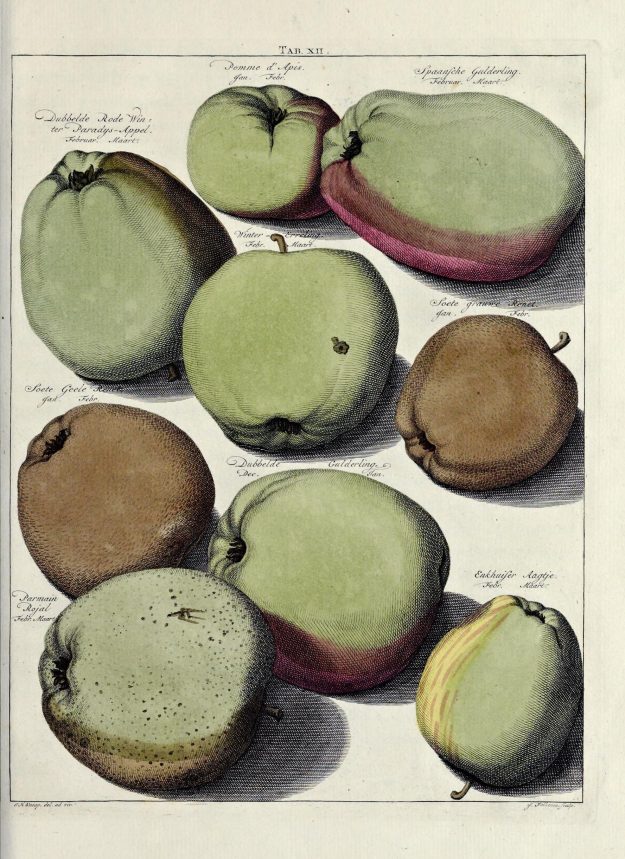

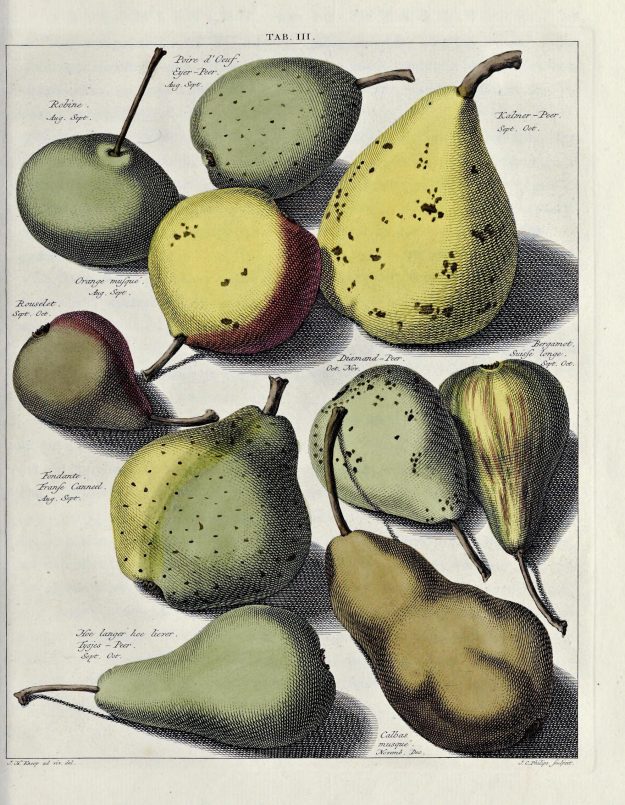

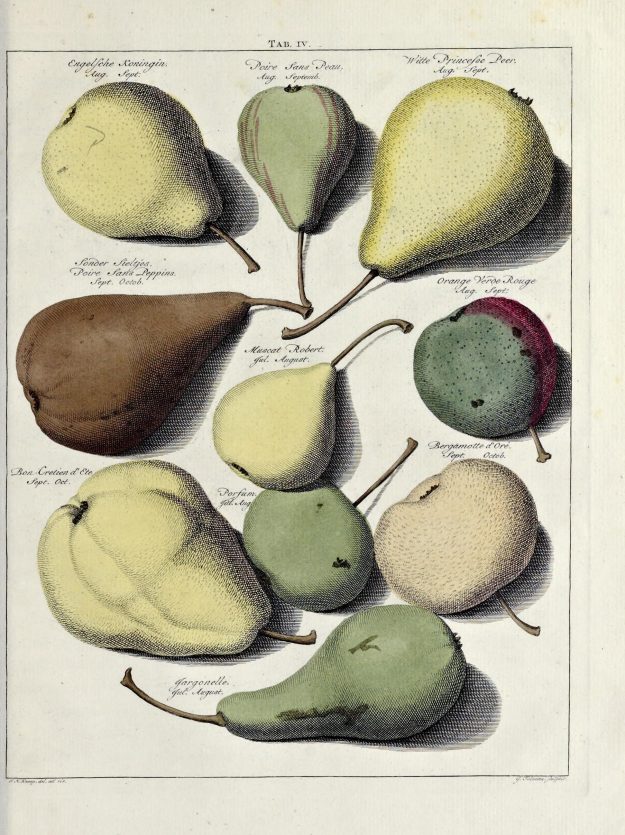

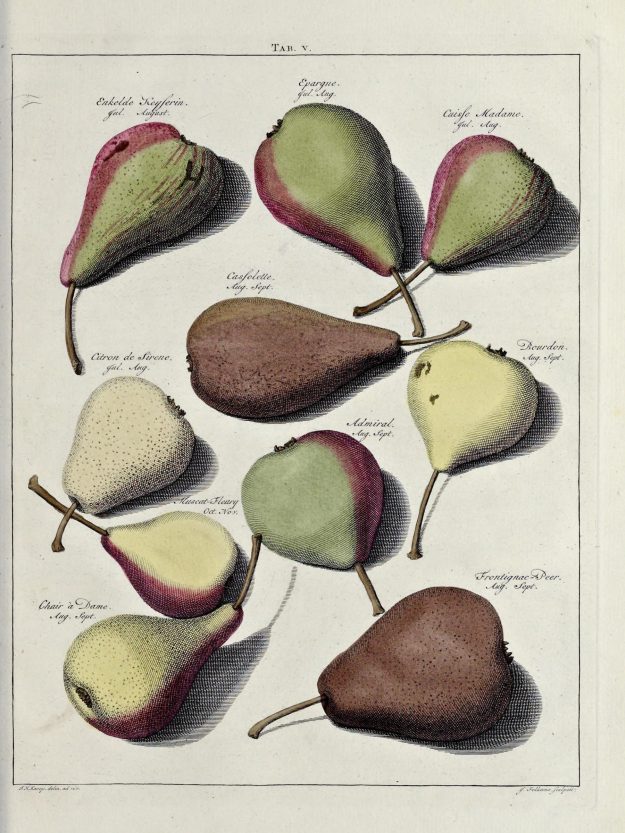

A wooden sign indicates a narrow path with steps down to the orchard and kitchen garden. An impressive lean-to glasshouse placed against one of the walls is used to house tender plants and raise seedlings and cuttings for the garden. The perimeter path passes the orchard where over thirty heritage apple varieties are planted, and leads to the kitchen garden, enclosed by a series of espaliered apple trees, supported by a metal framework. Here, crops of vegetables and soft fruit are complemented by flowers – now with self-seeded forget-me-nots, and later in the season by perennial geraniums.

Despite the relative grandeur, there’s plenty of inspiration to take away from Fenton House that would work in a domestic garden. The purple flowered wisteria tumbling over the high wall above the orchard has been carefully trained in a relatively tight space, and espaliered fruit trees could easily be used to create a soft division between spaces. Other details, like the outdoor furniture, supports for climbing roses and terracotta rhubarb forcers create their own special atmosphere, whilst also being practical.

Some of us will remember a time when entry to the garden was a contribution by means of an honesty box, somehow adding to the charm of the place. In recent years, the National Trust has introduced ticketed entry to the garden, but fortunately the settled sense of calm throughout the garden hasn’t changed, and Fenton House continues to be a joy to visit.

Fenton House and gardens are currently open (bookable in advance) on Fridays and Sundays from April to October – further details below:

Snakes head fritillaries in the meadow

Espaliered fruit trees border the kitchen garden

Pale pink cherry blossom in the orchard

Further reading:

Fenton House and Garden here

A London Inheritance here