When microwave technology was developed in the 1940s, it was appropriated for use solely by the U.S. Military in order to further defense strategies during WWII. They used it for RADAR.

Following the war though, it was determined that the Army could make the science available to industry, so the technology could be used to devise a microwave oven for common use in American homes.

They called it a RADAR range.

At that time, the patent holders and the U.S. Army started looking at U.S. manufacturers to determine what company might best serve the nation by opening an entirely new and revolutionary market in American home cooking.

There were a number of leading appliance companies whose popularity among homemakers made them possible candidates to receive the new technology, but ultimately there was only one whose credentials fulfilled the entire necessary checklist:

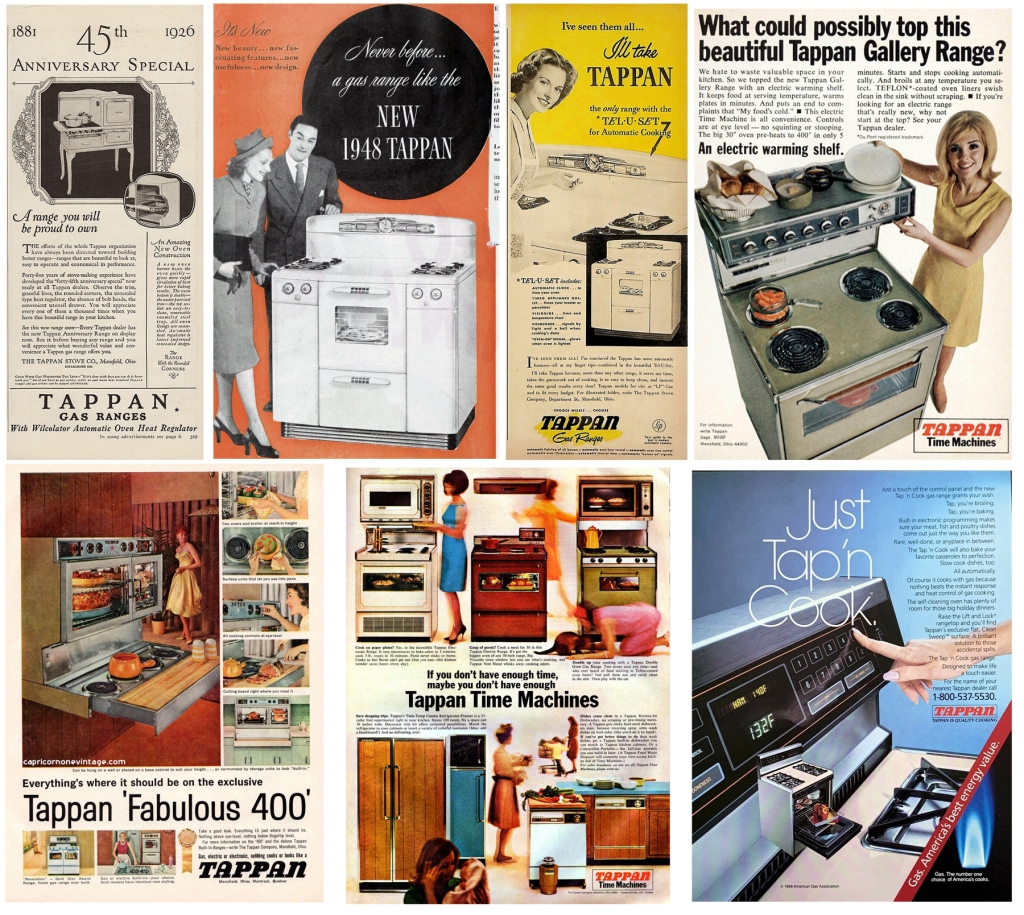

1) a reliable company capable of high-quality production;

2) a company talented and accomplished at marketing;

3) and a company already well-known for groundbreaking innovation.

It was the Tappan Stove Co. of Mansfield, Ohio.

The Tappan Reputation

It certainly helped that the U.S. Army was already very familiar with Tappan because of WWI: it was the Mansfield factory that had supplied American Expeditionary Forces with their battlefront rolling field kitchens in France.

But beyond that, the company was recognized for leading the gas and electric range industry in cutting-edge features which later became standard for other manufacturers. Tappan innovations were revolutionary at the time, yet so basic that we take them for granted today.

Things like:

1920s: The first thermostatic control of ovens

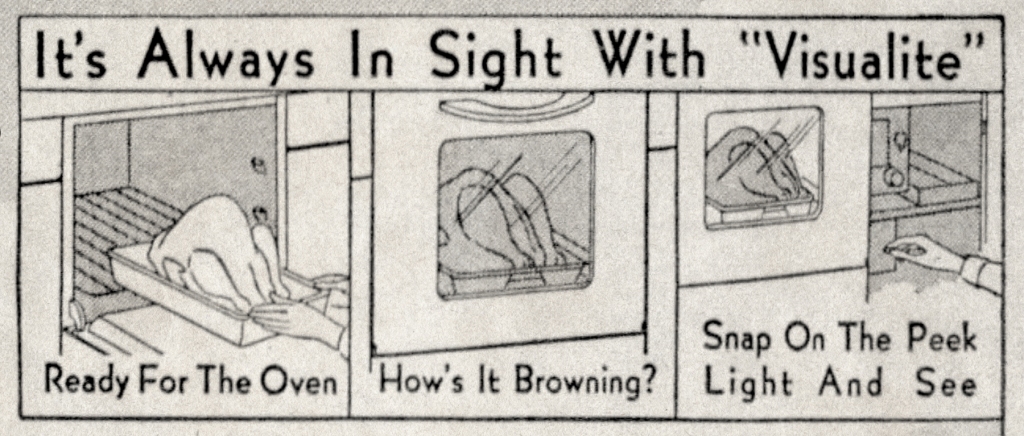

1930s: The first windows in oven doors

1940s: The first use of chrome accents & designer colors

When dirigible aircraft took to the skies in the 1930s, Tappan devised the first “lighter than air” kitchens for cooking safely onboard. A decade later, Tappan perfected these kitchen facilities for preparing in-flight meals on airliners.

Throughout the early 20th century, Tappan had become increasingly prominent across the entire nation by advertising in all the most popular magazines.

Tappan was the first to put windows in their oven doors.

Homemakers in the 1920s had begun to cook with heat-resistant glass called PYREX, so Tappan got permission to try it in their oven doors.

By 1938, Tappan had devised their own heat-resistant glass that they called Visualite, and American baking entered a new era.

The Tappan Microwave

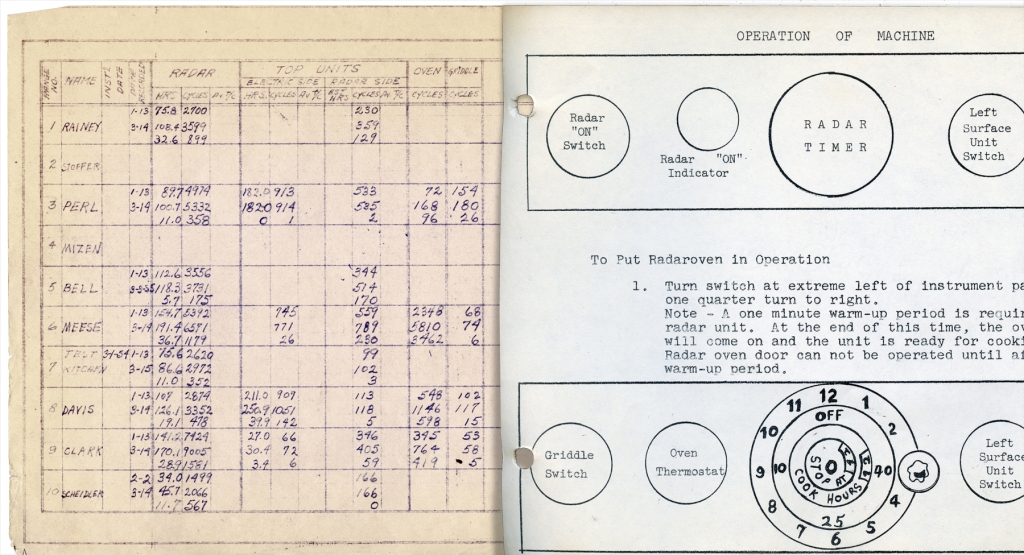

When Tappan engineers on Wayne Street received the first blueprints from government sources, the whole concept of microwave cooking applied science was so secret they weren’t even sure what they were building.

The first model they put their name on was actually half designed by the patent holders at Raytheon. It looked impressive, but it weighed a lot and it cost nearly as much as a new car.

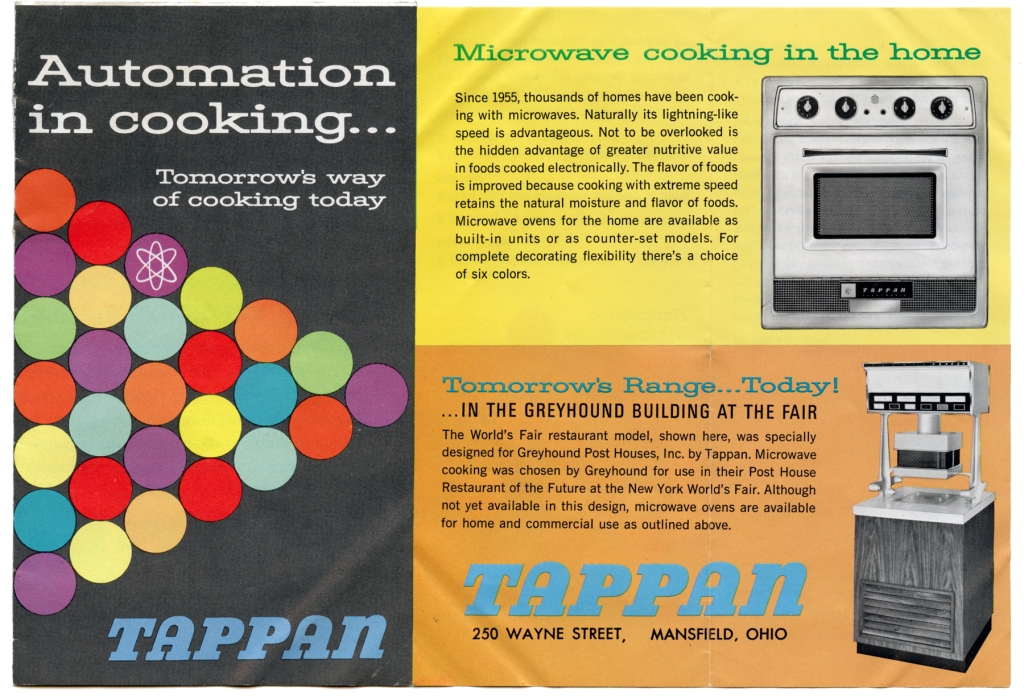

Before the grand unveiling in New York City, Tappan staged a preview at the Wayne Street factory in 1955 for reporters from the Mansfield News-Journal and the Wall Street Journal, where a local housewife donned her apron to demonstrate poaching an egg in 20 seconds and baking a cake in six minutes.

The official nationwide presentation—and the date that historians use for the Birth of the Microwave Oven—was October 25, 1955: the day when W.R. Tappan presented his baby to the national press at the Hotel Pierre on Fifth Avenue.

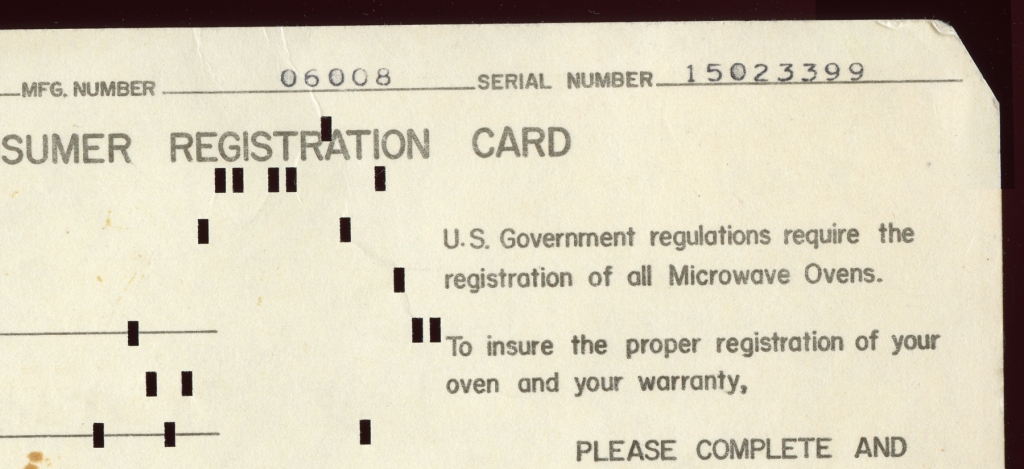

The first model weighed “only 150 lbs.,”and was powered by a magnetron which converted electric currents to those like high-frequency TV signals, so each oven sold had to be licensed by the Federal Communications Commission. Sales brochures assured homeowners that their new oven would “not interfere with either radio or television reception.”

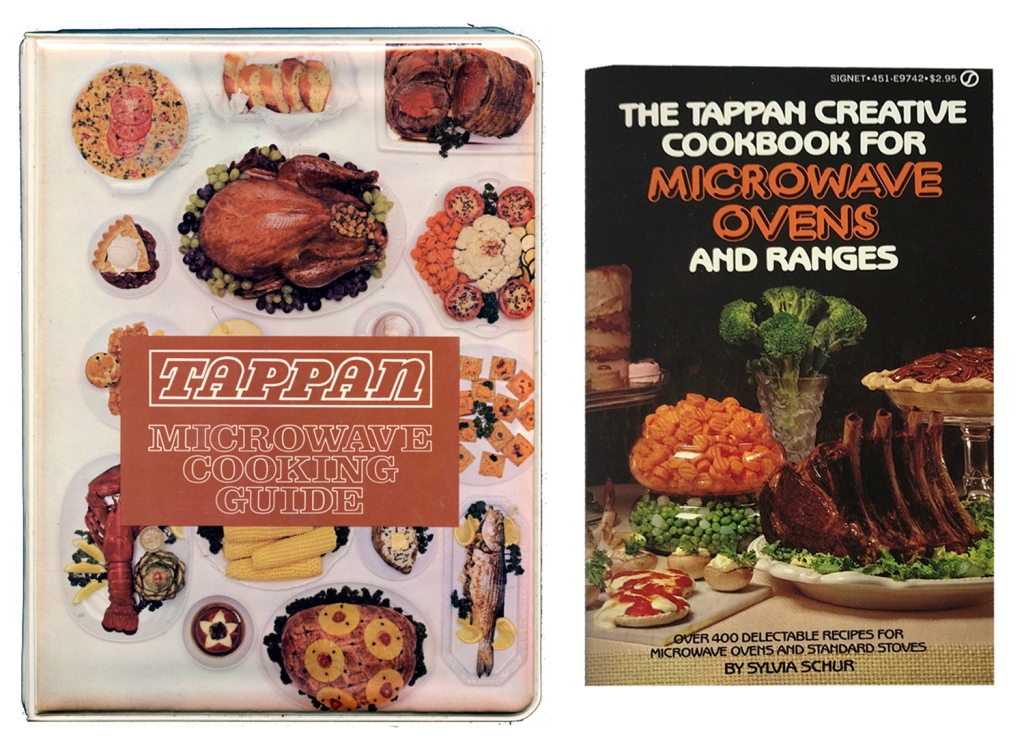

Seen above on the left in its original loose-leaf binder format, it was, for decades, considered the gold standard of microwaving fundamentals by appliance industries and publishers alike.

World’s Fair

When historians of our time write about visionary elements of the 1964-65 New York World’s Fair, and particularly about the things we take for granted today that were wildly futuristic at the time, there are two main exhibits they seem to always mention:

1) America’s first glimpse of the Ford Mustang; and

2) America’s introduction to the Microwave Oven as presented by The Tappan Company of Mansfield, Ohio.

The Tappan exhibit was very practical and hands-on, located inside the Greyhound Bus pavilion where diners could select pre-packaged courses from a variety of American regional cuisines, and then heat up their meals “at the push of a button” in a Time Machine: the oven that saved every housewife hours of toil.

Now We’re Cooking

Those large Radar Range models were designed to be built into a wall and, consequently, seldom got into smaller, older homes, and accordingly, never sold very well. After more than a decade of heavy promotion there were only 1,389 actually in use.

The Tappan engineers had been diligently tinkering during that decade however, and their completely revisioned concept was developed wholly on-site with the Mansfield kitchen in mind. It hit the stores as a counter-top oven in 1969, effectively opening the door for an entirely new era in cooking.

It was worth the wait: by 1974, Tappan had three different models available for under $300, and they had sold over a million of them. Sales of microwaves pushed the Mansfield plant to its all-time high employment of 1,200.

The Time Machine

The first ovens that Tappan stove makers made were heated with wood and coal, and then they pioneered gas, and then they led the way into electricity. It is entirely appropriate that Tappan would be the first to leap into microwaves.

If they were still here today they could tell us what’s next.

Thank You:

This article was made possible by the thoughtful first-hand knowledge of Bob Lamb and Tom Nixon, with images from the Mark Hertzler collection and North Central Ohio Industrial Museum.

PS. Another Tappan Innovation: Product Placement

Tappan was determined to get their ranges in front of women all over America, and they did their best to get into every newspaper and magazine that a woman might pick up, but they hit the jackpot in 1939 in an entirely new and unforeseen advertising medium: major motion pictures.

It started in 1936 when Clare Boothe wrote a play called The Women, with a cast of 44 women, that broke box office records on Broadway so enthusiastically all women across the nation were eager for it to become a movie.

So, Mr. Tappan went to Hollywood to see Mr. MGM and talked him into making sure every kitchen scene took place in front of a Tappan range.

I still have my Tappan microwave and use it regularly bought it back in 1975 in the UK

LikeLike