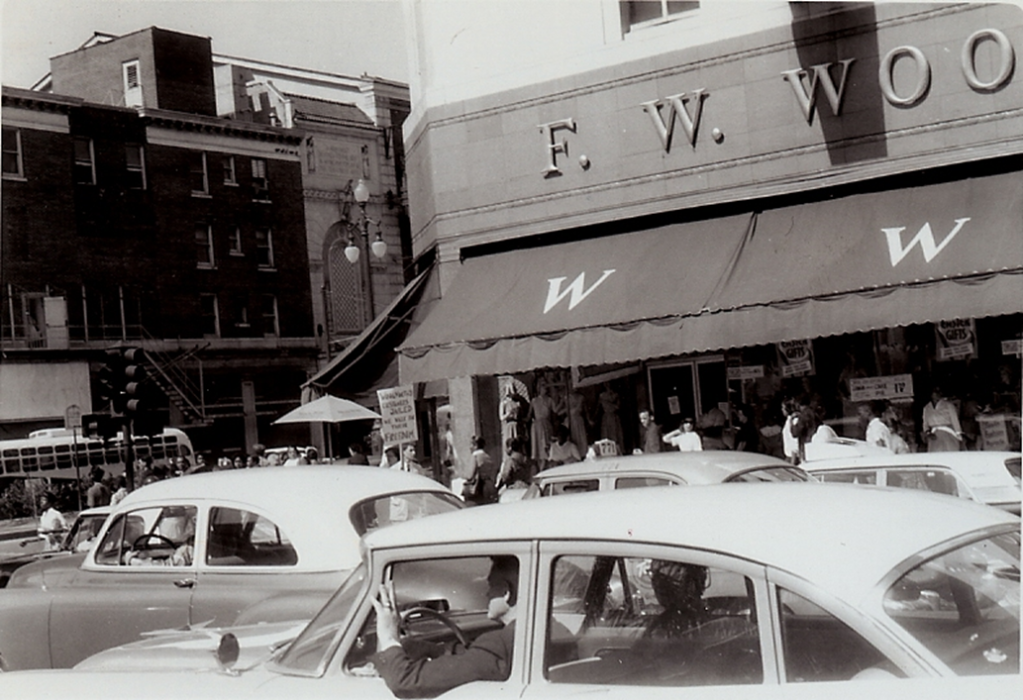

I found these photographs in a box of old stuff last week. (December 2018) They are photographs I took in New Orleans in 1961. They are 2¾ in. x 4 in. prints produced by a commercial drug store or camera store photo-printer. A few have “May 1961’ stamped on the back by the film processer, but the photos were probably taken earlier. There are no texts with the photographs. Frankly, while I had not forgotten the protests, I had forgotten that I had made these photographs. They are of a civil rights demonstration made by CORE, associated with sit-ins at of some Woolworth’s five & dime stores, which had not allowed blacks to eat at the lunch counters.

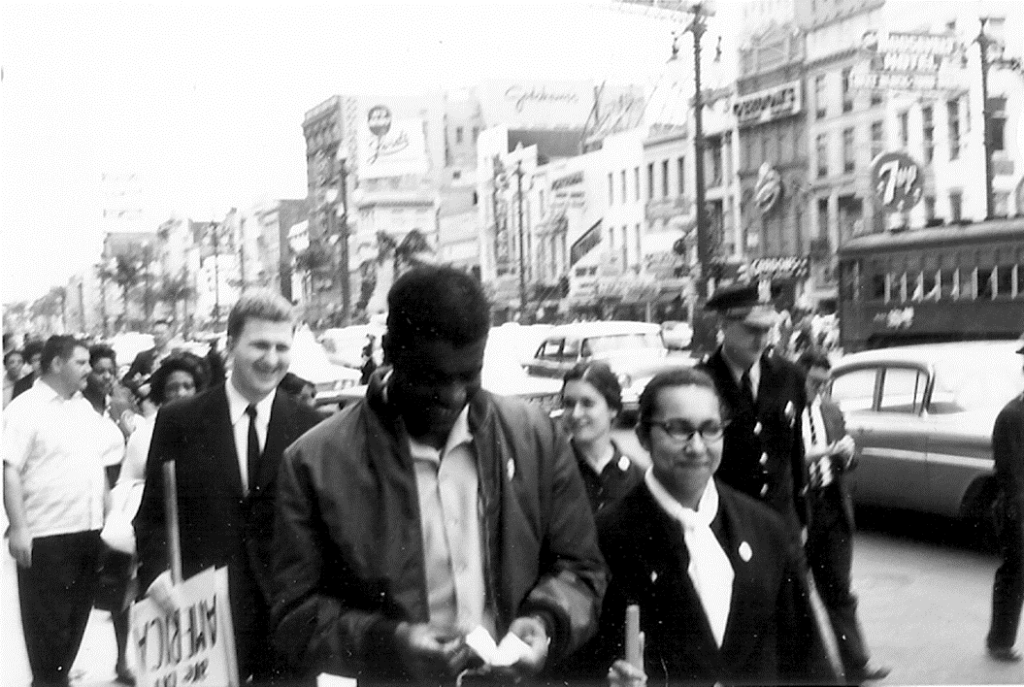

There were a series of these sit-ins in the in late 1960 and the Spring of 1961; and by this time a process had been worked out between the New Orleans police and the demonstrators. Early on, there had been some arrests, some of them violent, as demonstrators tried to actually sit at the counters. By the time of the event depicted here, the demonstrators, specifically pledged to non-violence, conservatively dressed and orderly, picketed the stores, walking carefully in a demarcated lane on the outside edge of the sidewalk. The police presence was there to protect the demonstrators from any mob action and then, at this time, arrest them without undue force, take them to a judge to be charged with some minor felony like public obstruction, and then be released on bail. The photos depict an arrest after one demonstration. The white male carrying the upside-down sign is Sydney Goldfinch. The name “Barbara Brent” is hand-written on the back of the print of the white woman carrying the sign “Don’t buy where you can’t eat.” I don’t know who any of the others are. I have just looked up some background information on the web and found out a lot more about the events than I knew at the time.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

“In 1960, almost 40% of New Orleans’ population was African American. The city’s main shopping avenue was Canal Street, where all stores were white-owned, predominantly Christian, had segregated facilities, and didn’t serve blacks at lunch counters. The second busiest shopping avenue was Dryades Street, where the stores were also white-owned, but store patrons were almost all black. Blacks could use the facilities, but were not employed in the stores aside from an occasional janitor. Many of the white storeowners were Jews, themselves prevented from owning stores on the more high-ranking Canal Street by the white Christian majority.

Late in 1959, Rev. Avery Alexander, Rev. A.L. Davis (SCLC), and Dr. Henry Mitchell (NAACP) organized the Consumers’ League of Greater New Orleans (CLGNO), an all-black organization, to fight employment discrimination by the Dryades Street merchants. Their lawyers, Lolis Elie, Nils Douglas, Robert Collins, Ernest “Dutch” Morial, and others, provided free legal counsel. For several months, the League tried to negotiate with the Dryades storeowners, but made no progress.

In April 1960, the League launched a boycott of the Dryades stores that wouldn’t employ blacks for anything but menial labor. The boycott was effective. The week before Easter was traditionally a good time for business, but on Good Friday the streets were empty. Shoppers were replaced by community members picketing the storefronts.

A few stores began to hire blacks, but most continued to refuse. The Consumers’ League claimed credit for thirty jobs for black people on Dryades Street. During the boycott, students from Xavier University of Louisiana (XULA), Dillard University, and Southern University of New Orleans (SUNO), New Orleans’ three major black colleges, and white students from Tulane and the University of New Orleans joined the picket lines on Dryades Street.

Over the next months, the boycott continued and customers took their business elsewhere. Many stores closed or moved to white suburbs rather than hiring Blacks. Dryades Street, once a bustling commercial center had become a ghost town.

The Consumers’ League boycott, apart from stopping business as usual on Dryades Street, helped cohere the black community in New Orleans. Lolis Elie claims the League was “in many ways a spiritual movement.” The boycott inspired other protests which led to the formation of the Citizens’ Committee, a federation of black organizations that worked on desegregating downtown stores, businesses and employment between 1961 and 1964. Also born out of the boycott was the Coordinating Council of Greater New Orleans (CCGNO), a federation of black organizations that organized voter registration drives between 1961 and 1965.

While the League’s pickets were temporarily stopped by an injunction, college students formed a Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) chapter led by former XULA student body president Rudy Lombard, Oretha Castle from SUNO, Jerome Smith (one of the students who withdrew from Southern University in Baton Rouge), and Hugh Murray, a white student from Tulane. Lawyers Collins, Douglas, and Elie agreed to represent the students in future actions after the ACLU refused.

On September 9, seven members of the new CORE chapter staged a sit-in at the Woolworth store on Canal Street. The integrated group of blacks and whites were arrested and charged with ‘criminal mischief.’ In contrast to the Dryades Street actions, the protest on Canal Street was seen as much more of a threat to the existing order because it threatened not the Jewish storeowners but the wealthy Christian elite of Uptown New Orleans.

On September 12, city mayor Chep Morrison issued a statement in response to the Canal Street sit-in claiming “the effect of such demonstrations [was] not in the public interest of [the] community” and “economic welfare of this city require that such demonstrations cease and henceforth…be prohibited by the police department.” The mayor banned further sit-ins.

Four days later, September 16, CORE field secretary Jim McCain, Reverend Avery Alexander, and other members of CLGNO were arrested for picketing stores on Claiborne Avenue. The following day, Rudy Lombard, Oretha Castle, Dillard student Cecil Carter, and Tulane student Sydney Goldfinch were arrested for sitting-in at the McCrory’s department store lunch counter. Goldfinch, who was a Jew, was charged with ‘criminal anarchy’ with a $2,500 bond and potential ten years in prison.

As police control increased, not only were sit-ins and picketers arrested, but also those handing out leaflets were arrested for ‘leafleting without a license.’ Halted by lack of bail money, CORE sit-ins continued sporadically as funds became available. Raphael Cassimire led the NAACP Youth Council, picketing storefronts to protest segregation and the arrests. Angry white crowds taunted, abused, and attacked the CORE and NAACP demonstrators, beating them, scalding them with hot coffee, and throwing acid on them.

Lawyers Collins, Douglas, and Elie asked John P. Nelson for assistance in representing those arrested on September 17. During the days following the arrests, almost 3,000 people attended a support rally for those in jail at the ILA (longshoremen’s union) hall, and SCLC leader A.L. Davis opened his church to CORE activists for meetings and training sessions in nonviolent action.

The most acute stint of action was over though some protesting continued for the next year. By late 1961, the economic elites of New Orleans were feeling the impact of the boycott.

Members of Chamber of Commerce and other local economic leaders formed a coalition to negotiate settlement to the protests at Canal Street stores and lunch counters. Storeowners were becoming nervous about continuing demonstrations and picketing by CORE and the Consumers’ League after news of struggling storeowners in Birmingham reached New Orleans.

Business leaders and leaders of the black community formed an informal conference to negotiate the desegregation of the town. Lolis Elie and Revius Ortique represented the black federation, known as the Citizens’ Committee, and continued negotiation that lasted for more than two years, eventuating in steps toward desegregation of the city. CORE agreed to remain passive during the negotiations as stores removed signs from toilets and drinking fountains and slowly increased black employment.

The New Orleans sit-ins, boycotts, and arrests continued for years, culminating in a large Freedom March in September of 1963. Very slowly, more public facilities were desegregated. Even though New Orleans integrated slowly after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Dryades and Canal Street boycotts and pickets helped black solidarity in the city and involved students in the civil rights struggle.”

https://nvdatabase.swathmore.edu/content/new-orleans-citizens-boycott-us-civil rights-1960-1961 (Dec. 28, 2018)

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

THE PHOTOGRAPHS. Copyright by William S. Johnson.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

I photographed this demonstration, but I also actually participated in a later demonstration, although I hasten to add that I wasn’t very political and I didn’t even know any of these people or any of this history until I read the above post today.

I was a sophomore at Tulane with a very simple, unadorned belief in justice and, apparently, a mild death wish. A friend of mine named Leonard Kratzer did have connections with some of these CORE activists and he told me about an upcoming demonstration and arranged for me to join it. On the day of the demonstration, edgy about both mobs and the police, obsessively humming Come by Yah to myself, I showered, put on dress pants, a white shirt and my only tie, (My normal clothes were blue jeans and a sweat shirt and I did not own a suit.) stuffed a pencil stub and folded paper in my shoe (for taking notes while in jail), and then Leonard drove me down to the demonstration on Canal street.

The way it was organized was that two people at a time, each carrying a sign, each starting at the opposite edge of the public space facing the store front, would walk up and down on the outer edge of the sidewalk in front of the store, crossing each other at the midpoint of their route, for the duration of their turn of picketing. (I can’t remember if the turn was for one or for two hours.) Then that pair would be relieved by another pair for their turn of patrolling the store. Everyone was supposed to be very polite, very correct, and very non-violent in their demeanor and actions. There was one other white person there that day, a blonde girl, who I didn’t actually meet. All the other demonstrators were very conservatively dressed, young, and black.

Leonard introduced me to the black girl who was my partner, whose name I didn’t really catch in the heat of the moment, I picket out a signboard, and then we started patrolling. I was 6 ft. 3 in. tall, weighed about 220 pounds, (The previous summer I had worked in a steel-fabricating plant in Ohio, and so was in pretty good shape.) and had a beard. (At this time beards were still so uncommon that they sometimes called for public comment, and I would be asked if I was Amish, a Jehovah’s Witness, a Hippie, or part of a rumored new social phenomenon that identified me as a Beatnik. I didn’t happen to be any of those things, but it comforted my questioner to place me in one or another category.) I was a little nervous as I picketed, which I dealt with by making some jokey comments to my partner while I paraded up and down. The point was that I didn’t look very respectable to my fellow demonstrators, nor did I show a sufficient gravitas to my colleagues, for whom this was a very serious, even life-threatening business, and everyone in our group seemed relieved when my turn was over without incident. My shift over, I left immediately – so I never even met the other demonstrators.

This photo has a date stamp of May 1961, so the demonstration had to have been sometime before that. But I may have waited until much later to get the photos developed up North, after I got back to Ohio. Oddly, this is the only photo that I have found of me demonstrating, although I’m sure the White Citizens’ Council files would have a few more.

And, to my mingled disappointment and relief, there was no confrontational incident. For reasons best known to themselves, the police did not make any arrests that day; and there was no howling mob of counter-protesters. This was, after all, not Mississippi, but New Orleans — the city which prided itself for being the most cosmopolitan in the South. The racism was a little more discrete and constrained in New Orleans.

There were only two small confrontations during my patrol, both, in retrospect, faintly risible.

The first was from a very old couple who strolled by me as I picketed. The man, probably 80 years old at least, almost five feet tall and, I swear, looking just like the Colonel Saunders — goatee and all — of modern TV advertising fame; quietly asked me as they went past: “How can you do this to your own people? To which I was quick enough to answer — “I’m doing this for my own people.” before they went out of range.

The second event was even less satisfying. As I paraded with my sign-board, another much younger but equally short, slight man kept dithering around, approaching me and breaking off his approach two or three times — clearly nerving himself up for a physical confrontation. Then he began to walk directly towards me. I caught his eye, slowly lifted the sign-board over my head with both hands and, basically, flexed my 220 pounds of steel-handling, hardened muscles, and looked like I was definitely prepared to fail the non-violent proscription of the CORE marchers. This fellow immediately spun around on his heels, ran across Canal Street — which was then thought to be the widest main street in America. (Several lanes for cars, a middle berm with two parallel trolley-car tracks, then several more lanes for cars) and from the opposite sidewalk yelled his angry opinions at me; (Curiously, with a heavy Spanish accent.) from several hundred yards away. Far enough away that I couldn’t really make out what he was actually saying.

So — with slightly deflated expectations for the day, I went back to the Tulane campus and the routines of student life, having played no very heroic role in the local movement for racial equality in America.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

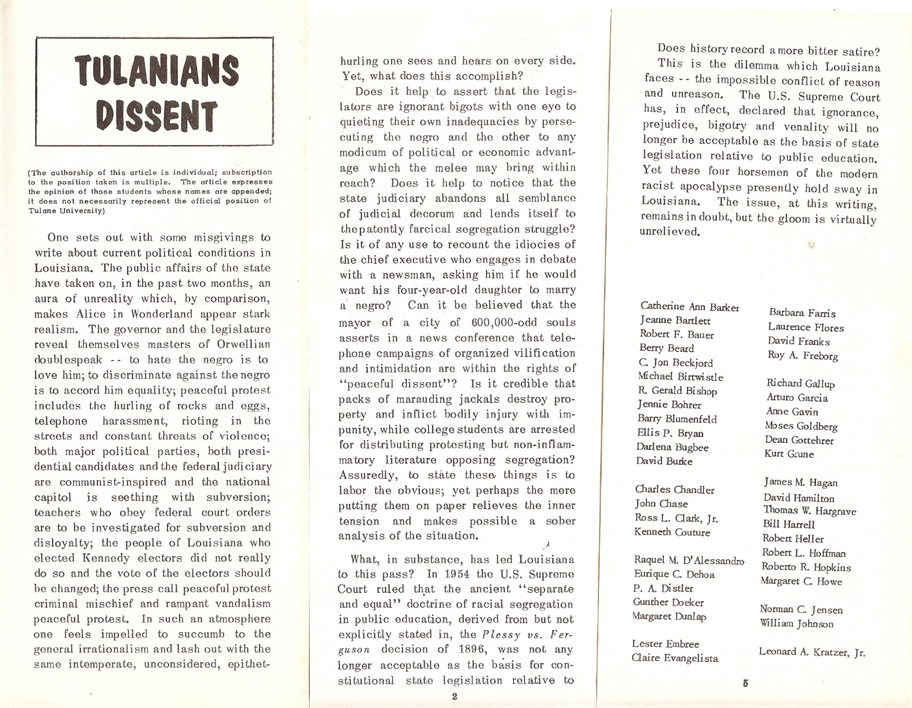

In fairness to myself I should say that I did do a little more on this issue while at Tulane University.

This staid and rather innocuous flyer created a small storm on campus when it was published. (Additional texts and other signers on the verso not reproduced here.)

Once or twice Leonard brought some of his CORE friends to the Tulane student cafeteria and I would casually join them for a chat at the table which was surrounded by a large circle of frozen silence. After a while, everyone finished their coffee and left without incident. But this was really a small form of political theater and an even more awkward social situation than normal for me, and I didn’t really get to know anyone during these events.

And as a Junior, the only semester I actually lived in a dormitory on campus, I was picked to share the dorm room with the Sydney Goldfinch who had been active in the CORE demonstrations and who was now out on parole; as the administration thought we might be willing to room together. I met Sydney once briefly at the beginning of semester, then he never showed up in the room again. But I did get used to picking up the phone to a stream of vile and obscene threats and calmly saying, “Oh, you are looking for Sydney. I’m afraid that he’s not here now,” then hanging up. One byproduct of the sit-in demonstrations was that the White Citizen’s Council, a right-wing, racist group would create a dossier on you, with photos, etc., and then tend to follow up with harassing phone calls and the like from time to time. Sydney, being high profile, got a lot more calls than I did.

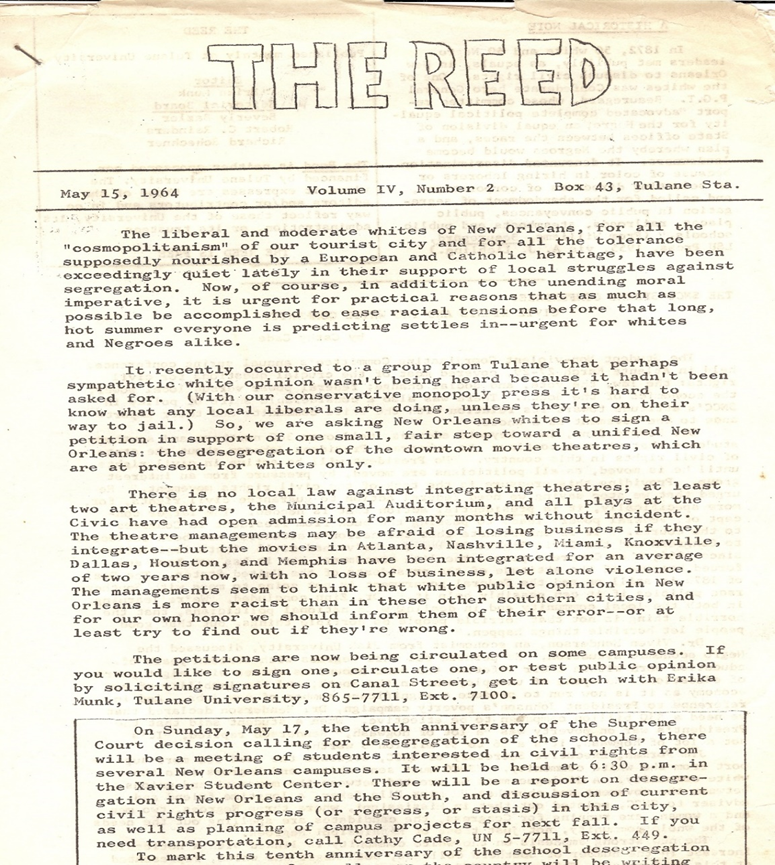

More significantly, I was a member of a small and very unofficial student group of political activists (mostly graduate students) who were determined to integrate the University. My role there was mainly to be the token undergraduate; however, I was also the editorial cartoonist and “Managing Editor” of the small journal/newspaper The Reed, which this group sporadically produced; running off several hundred copies on a mimeograph machine and distributing them around the campus. I worked as a part-time student assistant at the Tulane University printing office, so I had the skills and technology necessary for this position. I had earlier been refused a job at the university cafeteria because of the beard.

Curiously, given my Jackdaw nature, this is the only copy of the Reed I am now able to find, although I did get a complete set together for the Tulane University Archives, at their request, before I left town. I remember publishing several editorial cartoons on segregation, etc. in other issues of The Reed.

As “managing editor,” I recruited a small group of other undergraduates to hand out the paper around campus. Most of these were students from up north who had already decided that they were not coming back to Tulane next year anyway for academic or personal reasons. But, despite vague fears, there never were any violent confrontations about these matters on the campus. Tulane, calling itself “The Harvard of the South,” prided itself on its urbanity, had heavily recruited both students and faculty from around the country and abroad, and it was more liberal in its thinking than the surrounding city. Any overt hostility was suppressed, maybe only breaking out in the ferocious passion with which some of the fraternities — some southern, some New York Jewish — played each other in the intra-league softball games.

In any case, this informal student activist group did manage to embarrass the administration enough that the University did in fact integrate, admitting a single black man to the graduate Medical School program the year after I graduated, and within a few years there were black players on the Tulane basketball team.

But, never one for looking into the past, I lost track of what was happening at the University after I left, and afterwards I did not become involved in any type of political action, beyond signing an occasional anti-war petition during Vietnam. The equal rights movements intensified over the next few years, became extremely violent and vicious in some places, creating true heroes and many tragedies. Like most of my fellow citizens across the country, I followed these events with horrified disgust – but I was never again in a situation or place to actively participate again.

CODA

There was one odd situation that did arise later out of the White Citizen Council thing, and it was the only time that I personally felt actually threatened during the entire time. I happened to know a student, a former Marine, who, during the Christmas break, would buy an old banger auto, sell rides in the car to two or three students, then drive the car up to Cleveland, Ohio, dropping the riders off along the way, and then sell the car to some junk dealer – thus providing the cheapest ride for the students and a free trip home and maybe even a little pocket-money for himself. My parents were living in Wooster, Ohio at the time and I took this trip with him a few times. The only problem was that sometimes these cars didn’t always completely work, like the time we found out that the heater was broken when we got far enough north for it to matter.

Or, on this trip, as we were driving late at night through the endless pine forests of rural southern Mississippi, when a fuse blew and all the lights on the car went out. There was a full moon and a bright, clear sky that night, and one could almost see the trees by the side of the road in the milky moon light. So, the driver decided to try to tuck in behind some trucks and drive without lights until we would come to a truck stop where he could replace the fuse. So, we did this for about forty or fifty miles, suffering only one or two hair-breath escapes, along the way. I was sitting in the back seat behind the driver, when I realized that we were in Mississippi, and that if any police should see our car we would be stopped. The other students would probably be released without too much trouble, but with my beard and scruffy appearance I might have a little more trouble. This was the time when I began to seriously wonder about how connected the White Citizen’s Council’s files might be to other organizations throughout the South. In fact, I have to say that I really began to obsess about it during the hour it took us to find an open truck stop. But we did get to the truck stop, did find a fuse, were able to fix the car, and were able to drive out of Mississippi by morning. I have to admit to being very relieved when we drove over the state line into Tennessee.

ENDIT