The Vietnam War was the first major conflict that the United States lost.1 This theme of loss is made corporeal by a smooth black granite wall on the National Mall into which is etched the names of the more than 58,000 Americans who died. Unlike the monuments nearby that celebrate America’s victory over fascism in World War II or heroic troops cast in steel depicted bravely weathering the elements in Korea, the memorial to Vietnam is in effect a collective headstone. In America’s histories, movies, memoirs, novels, and commemorations, the war is often reduced to an American tragedy, this despite the troops from Allied countries who fought and died for the same cause and the Vietnamese themselves suffering casualties in the millions.2

By contrast, museums and memorials throughout Vietnam celebrate victory in the “American War,” which was the epilogue to a long and ultimately successful struggle for independence from foreign powers. These very different interpretations of the war—of failure in the United States and victory in Vietnam—illustrate how memorials do not simply present objective history. Rather, their narratives—including what they highlight and what they omit—offer insights into the society that created them. In this sense, monuments are a key part of the broader historiography, or the stories that we create out of history. What follows is a review of iconic monuments throughout Vietnam today to understand not only the Vietnamese experience of the war, but the public-facing narratives crafted from those experiences.3 In Vietnam’s case, it is at once a patriotic and Marxist story of an oppressed and exploited people achieving hard-won national independence from foreign imperialism, despite America’s attempt to prevent it.

Resisting the Chinese, Mongols, Japanese, and French

Today it is widely acknowledged that America’s seminal mistake in Vietnam was entering that conflict without even a basic understanding of the country or its people. Given America’s military might, such knowledge seemed irrelevant—after all, the United States had won two world wars and beat back Communism in Korea. Vietnam, on the other hand, was a slice of jungle the size of New Mexico inhabited by poor farmers. But the Vietnamese had millennia of experience fighting off powerful foreign invaders, and their modern identity as a nation was rooted in this proud tradition. Given the outcome of the conflict, Vietnam offers a clear lesson in the dangers of ignoring history and culture.

Beginning in 111 BCE for over a thousand years and later, northern Vietnam was part of or influenced by China. Northern Vietnamese adopted elements of Chinese culture including a writing system, Confucianism, and Mahayana Buddhism. This set it apart from its Southeast Asian neighbors, who were influenced by India and Islam. At the same time, the Vietnamese people maintained an independent spirit that inspired occasional rebellions. Perhaps the most famous of these occurred in 40 CE when the Trưng sisters led an uprising that bested the mighty Han dynasty, an episode still celebrated with a temple in Hanoi, a statue in Sài Gòn, and commemorative stamps. In the thirteenth century, when the Mongol hordes who had conquered most of Eurasia arrived at Vietnam’s shores, Vietnamese forces repelled the invasion and drove the Mongols back. China later reconquered Vietnam, but Lê Lợi led the Lam Sơn Uprising that decisively defeated the powerful Ming forces in 1427, ushering in an independent state of Đại [Great] Việt governed by the long-lived Lê dynasty.

This dual legacy of selectively adopting the culture of the colonizer while resisting foreign political domination persisted in the modern era. As European empires staked out colonies across the globe, France came to dominate Vietnam and its neighbors Laos and Cambodia, which the French governed collectively as Indochina. Alongside French language, food, and Christianity came economic imperialism, including coal mines and Michelin rubber plantations.4 To emphasize the vast lifestyle differences between the colonizers and the colonized, Vietnam’s National Museum of History exhibits the “Vietnamese people’s plight” with simple rustic plates, bowls, and chopsticks on a tatty woven mat within a reed hut, juxtaposed next to “the life of feudalists and imperialists and their collusion in Vietnam,” represented by ornately carved wooden furniture, delicately adorned glazed pottery, fine silk apparel, and a rickshaw ostensibly pulled by Vietnamese servants. While the display conveys an overtly Marxist message, it also explains why the promise of equality and a future liberation of the laboring masses drew support from so many in Vietnam.

As resistance grew, so too did French repression. A former prison on the otherwise-idyllic island of Phú Quốc has preserved the instruments of torture that French authorities used on dissidents, with both photographic evidence and graphic recreations of pulling teeth, removing fingernails and toenails, removing kneecaps, scalding, piercing with nails, crushing with weights, confinement in “tiger cages” lined with barbed wire, etc. Likewise, Hỏa Lò Prison in Hanoi, which would later serve as home to American POWs (discussed later), was originally constructed by the French in the 1880s to detain Vietnamese insurgents. It too has been converted into a tourist attraction, combining the characteristics of a historic site, museum, and memorial. Visitors enter through the imposing iron gates and walk through dark cement rooms to view rows of prisoners in leg irons or behind bars in cement cells, and at the extreme end, the cachot (dungeon), where prisoners were kept in solitary confinement. In all, “a total of 1,651 Vietnamese revolutionary patriots were arrested, kept and ill-treated by French colonists in Hỏa Lò Prison.”5 Significantly, the DRV (Democratic Republic of Vietnam, or North Vietnam) would later keep American POWs at the same prison, which makes for some awkward storytelling.

Hồ Chí Minh as Symbol of National Resistance

Just as earlier cultural heroes had driven out the Chinese and the Mongols, Vietnam’s modern mythology is constructed around a man who called himself Nguyễn Ai Quoc (Nguyễn the Patriot), later known as Hồ Chí Minh, who took up the mantle of liberator in the twentieth century. At the Hồ Chí Minh Museum in Hanoi, visitors are greeted with a smiling oversize bronze statue of “Uncle Hồ,” and then proceed through exhibits featuring relics from throughout his life. On the wall, a giant map highlights Ho’s travels from Vietnam to the US, then Britain, on to France where he helped found the French Communist Party, to the Soviet Union where he studied at the Stalin School. Hồ then traveled to China where, as a member of the Communist International organization, he worked with fellow Vietnamese exiles and supported Sun Yat-sen’s revolutionary government. Hồ stayed for years in China and ended up working with Mao Zedong and the nascent Chinese Communist Party, and by 1941 he had formed an organization known as the Vietminh (League for the Independence of Vietnam) to fight for the liberation of the fatherland.6

At the time, the world was engulfed in World War II. On its way to colonizing much of Asia, Japan had just invaded Vietnam, making the Japanese as much a target of the liberation movement as the French. In an ironic twist, the US sent officers of the OSS (Office of Strategic Services, precursor to the CIA) to Vietnam to nurse an ailing Hồ Chí Minh back to health and then arm and train his Vietminh to fight their common enemy. When the war finally ended, just hours after Japan’s formal surrender, Hồ Chí Minh mounted a dais in Ba Đình Square in downtown Hanoi to declare Vietnam’s independence before throngs of cheering compatriots. His speech, which began, “All men are created equal. They are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights…,” went on to quote both the US Declaration of Independence and France’s Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen. Despite invoking their ideals, Hồ would spend the rest of his life fighting against these two countries to realize that independence.

Exactly twenty-four years to the day after his landmark declaration, on September 2, 1969, Hồ Chí Minh died. Like Stalin and Lenin before him, and Mao Zedong and Kim Il-sung after, Hồ’s body was preserved and placed on public display. Today, thousands queue up each morning at the Hồ Chí Minh Mausoleum to shuffle reverently past his glass coffin and pay their respects (an estimated three million visit the masoleum per year).7 Indeed, the mausoleums of Communist leaders have become pilgrimage destinations, granting them a kind of secular immortality and suggesting that the revolution they embody lives on.

The American War

Despite Vietnam declaring its independence in 1945, when the defeated Japanese left Vietnam to return home, France still attempted to reclaim its former colony. From their headquarters in the north, the Vietminh waged a protracted and bloody guerrilla war until finally winning a surprise and decisive victory over elite French forces at Điện Biên Phủ in 1954. Under the Geneva Conference agreement that followed, Vietnam was divided into two states—the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) under Communist control and the anti-Communist Republic of Vietnam (RVN), also known as South Vietnam. A nationwide election was supposed to be held in 1956 to reunify the country. Hồ Chí Minh, hero of the revolution and national icon, was the favored candidate.

But the United States did not see the conflict in Vietnam as a war of independence similar to its own revolution. Instead the situation was viewed through the prism of the Cold War, with South Vietnam a domino threatened by Communist aggression emanating from the Soviet Union. With Hồ Chí Minh and the DRV already in thrall to Communism, the United States felt it had no choice but to prop up South Vietnam, or as senator and future president John F. Kennedy put it at the time, America would serve as the “finger in the dike.”8 In the late 1950s and early 1960s, as France gradually pulled its support from the south, an alarmed United States took its place, first with money, then with advisers and equipment, and by 1965 the Lyndon B. Johnson administration was sending American soldiers to defend a corrupt and unpopular RVN government. When the last remaining troops returned home a decade later, over three million Americans had served in Vietnam.

Weapons

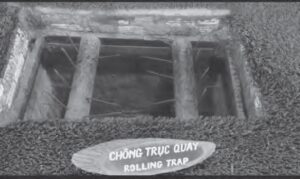

Today at both the DMZ (Demilitarized Zone that separated North and South) and the War Remnants Museum in Hồ Chí Minh City, exhibits display Vietnamese homemade booby traps alongside sophisticated modern munitions the US deployed against the Vietnamese. The former includes variations on a camouflaged pit dug into the earth and filled with spiked contraptions, such as the “rolling trap” (pictured), the “clipping armpit trap,” and the “seesaw trap.” Despite making steelsoled boots standard issue for US troops, gruesome injuries from such traps were not uncommon. On the American side, tourists learn about the intense conventional bombing that rivaled World War II, but also cluster and fragmentation bombs like daisy cutters, which scattered jagged metal fragments at high velocity just above ground level. Napalm, a highly flammable gel that burns at temperatures hot enough to melt steel, was first developed by the US for use in World War II but was later used in Korea and Vietnam, where it wrought devastation in both aerial bombs and flamethrowers. One of the most famous photos from the Vietnam War, referred to as “napalm girl,” won the Pulitzer Prize for Photography in 1972 for its raw depiction of napalm’s collateral damage on the Vietnamese population. Operation Ranch Hand implemented another type of chemical warfare in the form of herbicides that indiscriminately killed vegetation in order to expose guerrilla units ensconced in dense jungles or moving supplies along the Hồ Chí Minh Trail, but it was also used to deprive the enemy of food sources. The US government reports that nineteen million gallons of herbicides were sprayed across nearly four million acres in Vietnam.9 While an entire rainbow of defoliating agents was developed and deployed, each named for the color of the bands across the metal barrels in which they were stored and transported, the most widely used was the infamous Agent Orange. Not only did it wreak intentional havoc on the ecosystem, but the dioxin present in the spray has also been proven to persist in the soil, causing cancer and genetic mutations in animals and humans. Museum exhibits include harrowing documentation of the effects of Agent Orange on both Vietnamese and American GIs who were exposed.10 Today the governments of the United States and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV, the official name of Vietnam today) are working together to remove dioxins from former military bases in the South, where the poison is still found in high concentrations.

America’s intense aerial bombing campaigns drove both the citizens of the DRV in the North and the Vietcong operating in the South to take shelter in underground bunkers. Over time, these evolved into extensive, manually dug tunnel networks equipped for long-term survival, complete with food storage and kitchens, camouflaged ventilation systems, sleeping quarters, caches of weapons, meeting rooms with conference tables, infirmaries, and other specialized rooms, all well-hidden and of course booby-trapped. Today, tourists can appreciate the resilience and determination of the resistance movement by descending into the 250-mile Củ Chi tunnel system dug to surround Sài Gòn (although the tunnels have been widened to accommodate the larger frames of Western visitors) or the Vịnh Mốc tunnels at the DMZ (which are claustrophobia-inducing original size).

POWs and the “Hanoi Hilton”

On the flip side, American airmen who conducted these bombing raids across both North and South Vietnam were at risk of being shot down and, if they survived, becoming prisoners of war. There were several detention centers for POWs, the most infamous being the former French prison at Hỏa Lò discussed earlier, which residents referred to euphemistically as the “Hanoi Hilton.” Visitors to the site today are confronted with two jarringly different narratives—on the ground floor, where the dark prison cells and leg irons and dungeon are located, visitors learn about the severe living conditions and brutality the French inflicted on Vietnamese prisoners, while upstairs in the former staff quarters guests are told about the benevolent treatment extended by the Vietnamese within the same prison to those who had been bombing them. The late John McCain, airman and former POW who was captured and imprisoned at Hỏa Lò for over five years, detailed his experiences of beatings as well as physical and psychological torture undocumented in the museum.11 He also recounted his anger and refusal to participate in the staging of photos now on exhibit. Still, he returned to the prison after its conversion to a museum and worked to heal bilateral relations between the United States and Vietnam. His fellow inmate, Pete Peterson, ended up serving as America’s first ambassador to the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

The tour ends in a courtyard outside the facility, where a mural commemorates those Vietnamese patriots who suffered or died at Hỏa Lò Prison and an altar of burning joss sticks represents a perpetual offering to their memory. Implicitly excluded from the memorial are the American POWs who likewise suffered there, but for a different cause.

Tet and the Mỹ Lai Massacre

Although the American public initially supported the Johnson administration’s escalation of the war in 1965, as the war ground on and the cost rose in terms of both money and lives, that popularity waned and protests grew. A number of factors contributed to this shift, but prominent among them are the Tet Offensive and the Mỹ Lai Massacre (Thảm sát Mỹ Lai). After years of being told by their government that America was about to turn a corner and that light was appearing at the end of the proverbial tunnel, in early 1968 combined Communist forces launched a surprise offensive during the Lunar New Year festival known as Tet. Coordinated attacks across South Vietnam crippled military bases and even breached the US embassy in Sài Gòn in an effort to overthrow the RVN and overwhelm its American patron. The offensive ultimately failed, with the Communists sustaining heavy casualties and the southern population refusing to join in an anticipated general uprising. Still, news coverage of widespread carnage and ongoing street battles in southern cities alongside the appalling image of the summary execution of a Vietcong POW in a Sài Gòn intersection all broadcast on the nightly news back home shocked the American public, prompting widespread skepticism of imminent victory and mistrust of the American government.

Just weeks later, with American troops still spooked about Tet and angry over the recent loss of comrades, six platoons were ordered to clear Vietcong from a group of hamlets around the village of Sơn Mỹ. Despite encountering no resistance or provocation, soldiers began firing on residents. The killing quickly escalated, with some officers even ordering their men to round up and execute defenseless villagers. The slaughter went on for four hours, with the men even taking a lunch break before resuming. Although the death toll is disputed (see endnote 12), SRV government estimates are that 504 Vietnamese died in what became known as the Mỹ Lai Massacre.12

To commemorate the tragedy of March 16, 1968, a complex of museums and memorials was constructed at the site where the hamlet of Mỹ Lai 4 (the village Mỹ Lai had six designated hamlets, number four is where the massacre occurred) once stood. The tour begins with a documentary video featuring eyewitness testimonies from both victims and perpetrators, most memorably from Varnado Simpson, who confessed: “I cut their throats, cut off their hands, cut out their tongues, their hair, scalped them. I did it. A lot of people were doing it, and I just followed.”13 The museum then displays graphic photos of the many victims, including men, women, children, and even babies. Gory dioramas attempt to place visitors in the scene. Other exhibits include the personal effects of those killed, such as a slipper that belonged to a fouryear-old child and a bracelet from a seven-year-old girl. One floor of the museum is a dedicated gallery of culprits featuring oversize portrait photos with name, rank, and a description of the person’s actions that day, from soldiers on up through officers to a smiling Richard Nixon. Juxtaposed against these profiles is a shrine to Hugh Thompson Jr., the aviator who witnessed these atrocities, landed his helicopter between fellow soldiers and the cowering civilians, and then helped evacuate the wounded. Thirty years after the massacre, in belated recognition of his heroism at Mỹ Lai, Thompson received the Soldier’s Medal, the highest noncombat award bestowed by the American military.14

The centerpiece of the museum is an enormous black granite wall that lists victims’ names in a fashion similar to the Vietnam War memorial in Washington, DC. In this case, each name is accompanied by sex and age at the time of death all highlighted in gold, with victims’ ages ranging from one to eighty-two.

Upon exiting the museum, visitors are confronted with artwork that visually conveys the agony of both victims and survivors, including an ornately carved bas relief in wood on the wall behind the guestbook, contorted bronze statues representing the victimization of innocents, and a monument that implies mourning for the dead but also resolve for those living to remember.

Scattered across the grounds one sees the foundations of former “hooches,” or thatched huts, that once served as homes to Vietnamese families, each now marked with tablets bearing the names and ages of the deceased. On the path from one home to another, visitors walk a cement path bearing the imprints of bare feet and bike tread followed by GI boots, a unique memorial that not only prompts guests to imagine themselves surrounded by the chaos of that day but also symbolically conveys the idea of mighty America terrorizing a much poorer and vulnerable Vietnam.

Ending the War

In 1968, Nixon won the US presidential election with a promise to end the unpopular war. Upon taking office, troop deployment rapidly declined. On March 29, 1973, two months after signing the Paris Peace Accords, the last American combat troops departed Vietnam. North and South Vietnam continued their civil war until April 30, 1975, when NVA tanks rolled through the streets of Sài Gòn and crashed through the gates of the Presidential Palace. In a symbolic rechristening, Sài Gòn became Hồ Chí Minh City while the Presidential Palace was converted into a museum known as Reunification Palace or Independence Palace. The cavernous reception halls and beautifully decorated meeting rooms where the southern leadership once hosted US presidents and politicians are now open to tourists who view it as a symbol of either victory or failure, depending on their perspective.

As elsewhere, memorials to the war in Vietnam convey important aspects of that event, but each has its own focus and agenda and none by itself presents a complete story. The US memorial focuses exclusively on America’s war dead, without acknowledgment of those who returned scarred in body or mind, let alone those allies who died for the same cause. Likewise, the memorials today in Vietnam extol the sacrifices of those who fought for the DRV, while cemeteries of RVN soldiers were bulldozed and no memorials exist for the millions who sacrificed for the cause of the south. Hỏa Lò Prison simultaneously chronicles French abuse of Vietnamese alongside propaganda depicting benevolent Vietnamese treatment of American POWs within the same walls. Mỹ Lai fittingly includes a museum and memorial dedicated to that massacre, but no counterpart or even public acknowledgment exists of the Hue Massacre perpetrated by the Communists against fellow Vietnamese. All parties tend to commemorate their own victimization or heroism, and while those stories are worth telling, it is also important to consider the stories they don’t tell.

NOTES

1. This was not a conventional loss on the battlefield or surrender to the enemy; rather, this was a failure to keep the Republic of Vietnam, or South Vietnam, free from Communism, which was America’s primary objective..

2. South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, Thailand, the Philippines, and Nationalist China all sent troops that in aggregate numbered in the tens of thousands, and Canada sent support personnel. There are no firm numbers for Vietnam’s total dead, but troops on both sides along with civilians are estimated at around three million.

3. Unless otherwise indicated, photos were taken by the author at the sites indicated between 2017-2018.

4. For more on French colonialism in Vietnam see Pierre Brocheux and Daniel Hémery, Indochina: An Ambiguous Colonization, 1858-1954 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011).

5. From the introductory placard on site.

6. An excellent biography of Hồ Chí Minh is found in Pierre Brocheux, Ho Chi Minh: A Biography trans. Claire Duiker (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

7. This is according to literature on site at the mausoleum.

8. From “Remarks of Senator John F. Kennedy at the Conference on Vietnam Luncheon in the Hotel Willard, Washington, D.C., June 1, 1956” available through the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum website at https://tinyurl.com/ mrxenstc3c.

9. For an official summary, see the National Institute of Health report titled “Veterans and Agent Orange: Health Effects of Herbicides Used in Vietnam” (Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, 1994). The report is also available online at https://tinyurl.com/2xuns2bye.

10. Compensation is an ongoing issue for both countries. In the United States, a class action lawsuit led to creation of the Agent Orange Settlement Fund which made payments to victims until the funds ran out in 1997. The principal advocate for those suffering the effects of dioxin in Vietnam is the Vietnam Association for Victims of Agent Orange (VAVA).

11. Details appear beginning in chapter sixteen of his memoir Faith of My Fathers: A Family Memoir (New York: Random House, 1999).

12. The Vietnamese claim 504 deaths while the US government estimates 347, but basic facts about the event are not in dispute.

13. His testimony also appears in Michael Bilton and Kevin Sim, Four Hours in My Lai: A War Crime and Its Aftermath (New York: Viking, 1992).

14. Thompson’s story is chronicled in Trent Angers, The Forgotten Hero of My Lai: The Hugh Thompson Story, revised ed. (Lafayette, LA: Acadian House, 2022).