Italian cars and American cars: Who begat whom? Some examples of pre- and postwar influence, coincidence and serendipity (part 1)

01/29/2017

Text and photos by Matteo Giacon, except where noted.

[Editor’s Note: Most of you will probably know him as italianiron, a frequent commenter on our carspotting posts. But Matteo Giacon is more than just a carspotting savant; he’s also a part-time car writer and has put together a number of dissertations on Italian and American cars, including the one below examining similarities and links between the two countries' carmakers. Part 2 will follow next week.]

Since the early days of the 20th century, idea-sharing between the opposite Atlantic coasts was as common as fireworks during the Fourth Of July, but we usually tend to think that this occurred mostly between the United States and Britain, France or Germany, where the direct presence of American firms or American ways of thinking was widespread and quite common. However, Italy wasn’t immune from a certain trans-Atlantic influence, and the way Fiat organized its production is a good example of American influence on the southern side of the Alps. Although every main European carmaking country in the pre-war years had its own school of styling, it was clear that the real avant-garde ideas applied to mass-production cars came usually from the States.

Sure, the Citroen Traction Avant, many Peugeots, Pahnards and some Renaults, the Lancia Lambda, Augusta or Aprilia or the original Fiat 6C 1500s and 500s, the Flying Standards and some SS Jaguars, many late Thirties German cars like some Hanomags, Adlers, Horchs and the same early Beetles, and the Czech Tatras and Skoda Rapids are neat example of intriguing and advanced European cars available for the common driver, and although many German carmakers in the Thirties even built some exceptionally advanced prototypes and small-series cars looking very much advanced for the time, as a whole stylistic experimentation and research and development as we know it was, more often than not, the realm of renowned body builders scattered in all Europe, with France at the forefront of the glam, England at the forefront of the aristocracy and sporty elegance, Germany showing itself able to make both the most imposing vehicles and the already mentioned most outrageous experiments. And the Italian ones? Well, they offered a nice blend of all the aforementioned styling, and while during the Thirties in Italy there weren’t the outrageous creations of a Figoni et Falaschi, or some aeroextreme Spohn body, or the dignified elegance of Freestone & Webb, sure there was the ability to follow closely all the most important trends. Then came WWII, but once it ended, an incisive and unmistakable Italian style slowly began to develop and to prosper.

After the war, in fact, it seemed for a while that only Italy and England could continue to support R&D in the automotive realm extensively using coachbuilders, which this side of Alps became renowned as carrozzerie. This came about for a variety of reasons, mostly because all other European countries had to leave this approach or downsize their previous efforts as far as small series or one-off cars were concerned. However, despite the fact that English bodybuilders continued to prosper and there was a huge number of small firms continuing to experiment or building bodies for popular priced drivetrain, as a whole their efforts looked often a tad on the conservative side, this in accordance with the usually conservative tastes of their clientele; those relying on the sports cars concepts became full-scale carmakers like Lotus or continued as small firms, some transitioning into a booming kit car market. However, as a whole, they looked often like followers rather than real trailblazers, and pure R&D done with the production of pure concepts cars wasn’t apparently on par with the Italian efforts. Sure, there were firms like Ogle and pure designers like Trevor Fiore and Tom Karen, but their admirable efforts were seemingly somewhat less numerous than the Italian experiences.

The once great French and German coachbuilding firms had to suffer the departure of such glorious automakers that had assured them jobs and money, leaving the possibility of experimentation to mass-producing car makers only, and the French coachbuilders also had to bear the ignominy of an almost absurd tax application to luxury cars which literally was the last nail to the coffin of such marques like Delage, Delahaye, Bugatti, and many of the once great French coachbuilders, which appeared incapable of proposing and promoting newness and freshness of designs for smaller cars. As for Germany, what few had survived soon found more profitable a small series product derived with few differences from a mass-production car rather than pure and simple experimentation and the continuous effort to propose new designs, like the Italian firms as a whole were doing. Later on Germany would develop a strong tuning industry, but at least initially all the plethora of these tuners concentrated on mechanics rather than pure aesthetics, just like Giannini and Abarth in Italy during their infancy; only later they would become a force also in coachbuilding or conversions.

Sure, there can be some sort of disagreement about this analysis, especially because firms like Karmann, Hebmuller, Chapron and Mulliner Park Ward were still alive and well, yet they seemed conspicuously few when compared to the thriving Italian scene, where after the war there was a literal blossoming of talents, proposals, efforts, ideas and experiments. All this “forward thinking” - one could say a “giant step forward” - by Pinin Farina, Vignale, Viotti, Bertone, Ghia, Zagato, Frua, Allemano, Balbo, Monviso, Canta and many others, and the epic work made by singles the likes of Michelotti, Scaglione, Giugiaro, Gandini, Brovarone, Fioravanti, Boano, Sessano was possible thanks to a concomitance of events: Absence of foreign competitors for Fiat, Alfa and Lancia and relatively few domestic cars (so those desiring distinction usually asked for a carrozziere to come up with something “neat” and “different”), an already proven talent in developing new designs for sporty and sports cars, just like British builders, but working with such firms like newcomers Ferrari, Moretti, O.S.C.A. and Lamborghini and renowned ones like Maserati, Lancia, and Alfa meant that a pure and simple design by default would also result in less weight, hence the resulting car had more chance to enter the winners circle. This alone can explain such masterpieces like the Ferrari Barchettas and Berlinettas, the Miura, and the various spiders and sports cars blossoming like violets in April. But we also need to add the ability to cope with the new problems linked to the upcoming Fiat compact cars which would be for many firms the backbone of their production – in other words, the most common Fifties and Sixties Italian cars were perfectly suited for the typical carrozziere’s job and vice versa, with designers finding good solutions to the problems of rear engines and transmissions and unibody layouts - and most importantly, a very low labor costs, with skilled talents spread almost everywhere available at a fraction of the costs endured in other countries, all this while the prewar “natural” attitude to follow and eventually improve the best “new” ideas coming from both in-house and abroad still persisted. Soon, it became clear that Italy could compete with what was then the best concentration of designers in the world, Detroit, and soon even U.S. firms saw that Italian designers were doing in their own personal manner exactly what Big Three and Independents were already doing, often bettering them, because in their continuous effort to develop better sports cars the like of Alfas, Lancias, Oscas, Stanguellinis, Ferraris and Maseratis they had not only to avoid excessive weight - which was not a problem for a Mercury or Buick designer - but they also needed to follow the mantra of the Longer-Lower-Wider ideals, or in other words the proportions so familiar to the typical high-end Italian coachbuilder were very much the proportions sought after back then by the typical Detroit in-house design studio. Thanks to a cut-rate labor cost, it was no surprise then, and it is still no surprise today, that so many Italo-American joint ventures were soon developed : all those Chrysler-Ghias, the cars seen after Pininfarina started to work together with Nash, especially the Nash-Healey, the Bertone-bodied Arnolt Bristol (yes, an English-engined car, but born out of an idea by Wacky Arnolt, 100 percent American), the Touring-bodied Hudson Italia and so on are all examples of this trans-Atlantic relationship. Many of them were simply American designs built to order, think about the Chrysler K-310, the same Hudson Italia or the Packard Predictor, yet there was a reciprocal convenience in all this work and idea sharing.

So it was quite clear that it was not only a matter of Italian car designers influencing American firms, in reality the contrary was also true, more often than not, and this especially when marketing departments, in Fiat especially, desired to have the last word in the birth of a new car. After all, in many marketing men’s minds, American designers ideas had to be considered in Italy as one of the best possible, and this for a simple reason, a reason which nobody in the whole Europe seemed to be immune to: For something like twenty years after WWII, European car makers followed typical U.S. ideas while designing their next standard cars, and this because of that well known fad that dictated, since the late Forties, that everything coming from America was the truly best and newest of the possible things needed for a better living, from the A-bomb to the latest dishwasher. Speaking of automobiles, however, while it is quite expected that in countries where U.S.-owned factories were well alive and thriving this kind of influence was obvious (think about English Fords and Vauxhalls, German Fords and Opels; even the French Ford Vedettes, soon to be Simcas, when they debuted were striking in their own ), in Italy it seems like there could be no room for U.S.-imported ideas to spread or even to be deemed as barely acceptable and all those aforementioned relations between Italian designers and American designers seemed like they had to be grandly diluted if there was some willingness to propose or to sell to Italian buyers. Instead, surprise! Italians were simply mad for everything coming from the United States, especially what American citizens could normally buy but Italians had still to wait for, because the real prosperity was still in the future. This would arrive soon, very soon, but in the meanwhile Italians dreamed of America, rather than having a glimpse of the typical American taste as far as appliances, foods, cloths and general life-style was concerned. Wherever possible, however, Italian consumer goods producers were already more than happy to offer Americanized items to buyers, and all this not only because there was the idea of an American supremacy in the way consumer goods were produced, promoted and sold, so copying them was a good way to enter the perceived uppermost modernity, it was also because, thanks to America, Italy was now experimenting something very akin to the typical Italian mood: democracy, and then individuality - especially in those days, Americans were the Liberators, not the Winners, so trying to follow them and their way of life was not an imposition, but a pure and simple pursuit of freedom. All things considered, one of the first “consumer goods” realm where the American way of life could be met by someone with money to spend was the automotive world. So, in lieu of all this, we will see that, despite the idea that Pininfarina and all the others were at the absolute forefront of the car design in Italy – and in doing so, offering almost mandatory-to-follow style directions - and despite the general perception that typical Italian cars were exactly the opposite of an average American car, there were many examples of Italian cars influenced in no modest manner by what Detroit, Flint, Willow Run, even Kenosha or South Bend offered. It is now time to show some of them.

The Kaisers And The Fiats : When Willow Run Was The Center Of The World

The connection between Kaiser-Frazer and the 1950 Fiat 1400, the first postwar Fiat and one of the watershed design for the Turinese marque, is a well-known one; to put it shortly, after the war there were contacts between both Fiat and K-F for a commercial agreement of sort, there were even talks about selling Fiats in the United States through K-F dealers and also talks about a Fiat takeover by K-F itself but nothing proceeded. However, because Fiat sorely needed both new models and toolings, dies and materials for producing them, they had to resort to asking Americans for help, using funds allotted from the Marshall Plan. When Italians put the question about what was better to build, American authorities suggested to create something close to the then-current U.S. tastes, should the car be proposed on the American market, and so permitting Fiat to repay its funds in a way not unlike what were doing some English automakers exactly at the same time: a strong export effort. Not only that, but it needs to be remembered that many a head honcho at Fiat was thinking to move the entire production operations in case in the 1948 Italian elections, Communist Party should have won; maybe some of them were ironic about this, but others were surely concerned (after all, with the Commies winning, what kind of American money sources could be used then?) but at this point the new car had almost the need to look like a Yankee vehicle. This didn’t happen, because elections were won by De Gasperi and not by Togliatti, but the idea of building a car quite similar to the most advanced ones then available was already well established, especially because Fiat had already sent its best engineers to America in the spring of 1947 to study the latest and best techniques in the automotive mass production, preceding both the 1947 Marshall Plan approval and the 1948 Italian election.

During this “expedition” there were approaches with the renowned Budd firm, among others. When the definitive look of the new Fiat was finally locked in 1948, Budd helped Fiat in developing the new model and in preparing the needed tooling, especially new techniques and new stampings, and so, with Budd having helped Nash in developing the 600 in 1941 and Kaiser Frazer itself, it’s no surprise to see that the new Fiat was a unibody sedan technically similar to a Nash and stylistically close, very close, to the Willow Run Pride (Fiat was already experimenting with the monocoque body since before the war, but decisive help arrived through the Budd’s advise). The Fiat 1400 also owed much to the obscure Cemsa Caproni F11, the first front-wheel-drive car to be built in more than one or two prototypes only, but this last one certainly uses many contemporary American ideas, thanks to the pragmatical approach followed by Bertone when the F11 was styled. Interesting to add that the Tatraplan’s front end bears a notable similarity with the one used by the Cemsa-Caproni, but this leaves nothing to the newness expressed by this obscure Italian Etceterini. Despite this, the 1400 is the most famous of an unsuspected number of Italian cars owing much more to American stylists rather than to some renowned Italian designers or other notable European automotive glories.

Interesting to see at this point that apparently the 1400 wasn’t the last Fiat model to bear stylistic similarities with a K-F product: Five years later, the profile view of the world-renowned 600 looked like a Henry J devoid of fins and with a much stubbier nose, and some peculiar traits of the notorious little American car could rather easily be found in the immortal Italian supercompact! Needless to say, I don’t know if once again Italian designers and engineers took some direct cues from the American proposal, yet it is clear that among the many fastbacks seen during those times on both sides of Atlantic, the most obvious similarities between the Fiat 600 and some other car were the ones between it and the Henry J. Sure, technically the Fiat 600 was another thing entirely, yet if seen from certain angles, looks like a Henry J that began to smoke too young, just what Tom McCahill said of the Henry J when compared to a Cadillac Sedanet!

Studebakers, Pontiacs, Buicks And Those Italians With Big Faces

However, the Fiat 1400 wasn’t the very first Italian car to bear striking resemblances with some American product: Although its very early prototypes looked like scaled-down ’41 Plymouth town sedans, there was at least another Uncle Sam’s car heavily similar to later Italian Fiats, and this one didn’t come from Detroit… but first things first.

In the late Twenties and early Thirties, many Italian cars looked exactly like small scale copies of Detroit products, but one can always say that practically the entire world automotive industry production had the same lines, the same proportions, the same detailing. Also some Detroit cars looked gracefully European, just a quick look at the original LaSalle and this can be easily found; so, while there were already some commendable efforts by both Americans and Europeans to give more personality to cars that in that era had it more or less confined to the front end aspects, surely when these efforts involved mass-produced cars even back then Detroit was at the forefront of experimentation. Fiat, always keen to use the best experiences to improve its business, especially in those terrible Depression years, was one of the most faithful marques to adopt things first seen across the Atlantic: the ’32 508 Balilla, looking every inch like a cute Ford A or B Tudor, or the second generation 524, with its inclined grille, windscreen, and skirted front fender, already debuting in 1933 after only a year or two these solutions were adopted by Grahams, Hupmobiles, Cadillacs, are two valid examples of this quick-reaction attitude to make its standard products both feasible for the assembly plant economics and their usual would-be buyers tastes.

After this premise, I quickly come back to the subject of the title. In the Thirties, there was in Italy a well-known Italian man with a square-jawed face, his job: dictator. However, in those years, some more delicate souls (Dante Giacosa and Mario Revelli De Beaumont) back in Turin were designing cars which bore no resemblance with massiveness or brute force, relying instead to a soft touch with the incoming air: Those were the Fiat 1500 6c, the 500 A (the Topolino, aka Mickey Mouse) and the 508C, the original Millecento. The first one, especially, looked like the Chrysler Airflow continued across the sea with its faired-in headlights and the gently curved “scudetto” shaped grille created with 1934 Chryslers and DeSotos Airflows in mind. Although from the rear it also appeared distinctly close to another American aerodynamic offering: the Hupmobiles that had debuted in 1934. It possessed a lightness and purity of lines making it a real masterpiece with a distinct personality - after all, it was styled by the very talented designer Mario Revelli De Beaumont, and it is still widely appreciated now. However, that look didn’t seduce the Italian public too much, and not exactly for political reasons: Simply put, the people destined to buy the larger ones of the Fiat trio wanted some more “aggressiveness” (always linked to prestige back then), or they were usually too conservative and so not yet ready to wind-raked novelties like that, staying quite “unimpressed” to this kind of wind-penned beauty (and so the Italian public reaction was similar to the American public reaction with the Airflow: a rather cold one), or they were practical-minded guys who thought there was need to see where the car’s nose ended; after all, those happy folks able to ask some renowned carrozziere to redo their 1500s or 1100s soon began to demand more imposing and authoritative front ends nonetheless, and if firms like Viotti, Farina, Castagna or Touring obliged, why not Fiat itself?

In sum, starting in 1939, firstly the 1100 and then the following year the 6C 1500 adopted their peculiar prow-like nose, becoming known as “Musoni” ( Big Faces ) to make all those would-be buyers happy (the 500 would-be buyers were happy nonetheless, they usually promoted themselves from bicycles, motorbikes or trolleys, so they were less fastidious about styling details). Others in Europe had something like what was adopted by Fiat, the prow-like front end became another late Thirties fad. So, it is easy to see that many an American car could have been inspiration enough for Revelli De Beaumont and Fiat, after all even ’37 Pontiacs or Buicks or a ’38 Chevy bore some resemblance with the “new look” Fiats, the ’39 Cadillacs reverted to a decidedly pointed front, and the ’36 and ’37 Fords had a nicely vee'd grille, but the most similar front end to those Italian ones still belongs to the aforementioned ’37 Studebaker, right up to the alligator-type hood, and the vents running the entire front end length. Quite curious is the fact that, of all things , Studebaker had a model named Dictator still in the lineup by 1937 and I always found “interesting” that among all the possible prow-like grilles to “inspire” Fiat, the most similar one looks to be the one coming from the only car maker naming one of its product with the “technical” term used to describe what Il Duce was all about.

As a last note, it is interesting to say that more or less in the same years, while Fiat adopted its prow-like faces, on the other side of the Brenner Pass, The Austrian automaker Steyr used for its nicely advanced 50/55 a front grille quite close to the original 6C 1500/500 Mickey Mouse grille. Clearly, what was too much forward-thinking for the Italian public was beginning to be decidedly “in” with the public in other countries.

The Aprilia, The Ardea And That Aerodynamic New Wave

It is often thought that the Lancia Aprilia was Vincenzo Lancia’s spiritual testament, and story has it that before his untimely death he drove one of the prototypes and said “What A Magnificent Machine!” And indeed it was, because it was a thoroughly modern, sophisticated and truly nice car, one of the most advanced yet offered on the European market. It was always considered a typically avant-garde Lancia: It initially debuted as Lancia Ardennes for the French market only at the 1936 Paris Salon, and in the initial plans it was to be produced only in the French Lancia plants, where the Belna, the French Augusta, was already built. A market not prone to buy blatantly Italian cars in those post-Abissinian War months and the success of the Traction Avant precluded the French market, and so the car, now named Aprilia, debuted once again at Milan on October 28, 1936.

It sported a closed unibody monocoque, with the peculiar doors opening with no central posts, (anticipating the Cadillac Eldorado Brougham by 20 years), independent suspensions front and rear - although the roadholding in the first series wasn’t a strong point - and the typical Lancia narrow V-4 engine. It was a peppy car, good for 78 MPH back then, and refined in the most elegant manner a car with only a 1.35 liter engine could offer. But what set it apart was the striking styling, always considered an aerodynamic masterpiece (and with a CD of 0.47, at a time when CDs of 0.70 were the rule, it was true) and penned by in-house Lancia designer Battista Falchetto; the initial Standard cars were also offered with no running boards, although the vast majority of buyers opted for the Lusso model which bears them. The rear portion of the car is its most advanced feature, and the split rear window gave the car a strong personality, even if rear vision for the driver was compromised at best.

However, the Aprilia adapted to aerodynamic ideas then in vogue, rather than really introducing new ones, and many of them are quite close to what John Tjaarda had expressed in one of his most renowned masterpieces, the Briggs-bodied Sterkenburg series of concept cars (I always though that these have to be considered the first quintessential concept cars, instead of the ’38 Buick Y-Job, but this is merely an opinion of mine). Sure, as early as 1934 Lancia was studying teardrop shapes for its cars, and Turinese engineers had patented a design for a three-abreast front seat car penned as a typical teardrop. But it is clear that when since 1930, and surely as early as 1933, a car like the “definitive” Briggs-bodied Tjaarda car was making the round of automotive news all the world around, the car that ought to be compared with the new Lancia is the American one, and its direct heir, the Lincoln Zephyr. Three peculiar traits look common to the stock two cars: the teardrop shape implemented in the rear, the split rear window and a flat windshield, which gave the Lancia the impression of being even more like a smaller version of the Ford flagship.

However, it is important to remember that many automakers at the time were following these stylistic traits, especially after the Chrysler Airflow debut in 1934. In England, for example, since 1935, Flying Standards were already using the striking teardrop shape and the split window treatment. What set the Lancia apart from these cars were its virtual elimination of overhang, both front and rear, and the absence of rear quarter windows, which did nothing for the driver’s maneuvering needs, but gave the Turinese car a sense of sporty yet formal compactness and elegance.

The Aprilia wasn’t the only Lancia to use that formidable style intuition. In fact, in 1939 the Ardea debuted, for all the world a 9/10th scale version of the Aprilia, which maintained all its peculiar traits, including a V-4 engine, and in later series III and IV became also one of the very first cars to offer a standard five-speed manual transmission. But those thinking that the Aprilia was the Italian answer to the original Lincoln Zephyr and the Briggs Tjaarda-designed prototypes are likely close to the reality, after all a great designer always knows when a series of ideas and intuitions are good enough to be inspirational, and Battista Falchetto was a renowned talent of his own. The substantially different platform Lancia created for coachbuilders allowed them to show their creativity too, and many late Thrirties Aprilia were even more striking essays of aerodynamic applications, quite fit for a car too radical to be true, yet always considered as The Lancia. Under a certain light, not even an Aurelia or a Flavia can touch it as the quintessential Italian daring automotive exercise in so uncertain an era.

Catwalks And Alfas

The early postwar Alfa Romeo production was essentially based on one single chassis and drivetrain combo, the much coveted 6C 2500, which was produced as in-house styled Freccia D’Oro executive/club coupé and also as a plethora of truly intriguing coachbuilders creations, many of them true masterworks: Think about the touring bodied Villa D’Estes, or the dual twin headlights-equipped PF ’49 convertible built for the prince Ali Khan and the similarly equipped coupé, the 2500 Berlina also by PF, predating in some proportions the shape of the later 1900, or some others coming from Ghia, which sported the peculiar Supergioiello styling applied also on other frames and drivetrains, Stabilimenti Farina, Boneschi (which had a plexiglass portion above the windshield, and also a woodie by Viotti. The “stock” model, although built in respectable numbers for the Alfa Romeo of those pre-assembly chain era (albeit 700 examples are still a laughable number if someone doesn’t know the story of Forties Alfa Romeo) was always viewed as a somewhat strange car, especially from the rear, which gave the impression of being too stumpy.

On the other hand, the hood and front fenders lines were among the most advanced and graceful yet seen on an Italian standard production car, and something rarely seen also elsewhere: As said, the car sported flow-through fenders, just like a ‘41 Clipper, and the beautifully integrated headlights reminded some of the most delicate efforts seen on some other European cars before the war, and before the sealed beam days in America. Of course, its most personal feature, and soon to become the quintessential trademark of the Milanese marque, was its vertical “scudetto”-shaped (scudetto in Italian means “little shield”) grille. That was a nice redo of past typical Alfa Romeo symbols, but what set the new car front end apart was the adoption of those typically American features seen on many a ’38 to ’41 trans-Atlantic car: the “catwalks”, or lower laterally positioned grille running from the center of the front end and going close to the external edges of the fenders.

They were nothing new, even some European models had something like that in those days, but they are important for Alfa history because they later evolved in the “mustaches” first seen on the ’51 1900 and soon became a most powerful trademark for the most spirited among the Big Three Italian marques. Even the 21st century latest Giulia adopts them, albeit the very first set of them was quite unlike what was later standardized on Fifties 1900s and Giuliettas. In fact, they were simple grille openings set aside the vertical main grille, and divided by horizontal chrome bars, very much like a typical American sedan of 1938 to 1941 could have had, especially if sporting a tall upright central grille motive just like the Alfa did: think about a ’39-’40 LaSalle, a Packard of same vintage, (and those sported by the Freccia D’Oro shows a striking resemblance with the one used by the ’41 Clippers), even ’39 Plymouths, DeSotos, Hudsons, Nashes and all the other ’39 GM models but Buick. Also the simple little first Champions had adopted them, and if it is undeniable that they later evolved into the full-width grille opening that went widespread in the entire industry during the Forties, it is somewhat difficult to think that they continue up to these days as a true style symbol in Italy, all the more remarkable considering that the same evolution of the Alfa Romeo front ends missed them since the early Sixties. After decades of decadence, the “catwalks”, side opening grille, “mustaches” or whatever are named were resurrected in these last years and in quite an effective manner.

If Alfa had chosen yet another style for its very first postwar cars, likely we wouldn’t still have the Alfa Scudetto with us either. The “catwalks” helped to bring the Alfa style in the future, and at the same time helped to preserve the upright vertical grille image, and since then Alfas had no more identity crisis - well, almost. What’s more, I think that they were likely the first Italian cars to sport a precise family feeling set to last quite long, something that by the way only a few marques in the automotive world can brag about: Rolls Royce, Ferrari, Mercedes, BMW, Porsche and not many others. However, it is always curious to think, at least for me, that there were American cars setting a trend, at least for an Italian car, not because of a truly revolutionary and advanced idea, but thanks instead to the genteel evolution of a most traditional design, like the last LaSalles and the early Forties Packard effectively did.

The Italian Way To Metal Wagons

The typical American woodies had always teased the minds of European motorists since they became a staple in the Thirties market, and soon many became available to those with deep pockets. That’s because the classic wagon was still a luxury item beck then in the Continent, and also Great Britain, often considered the most prolific producers of European wagons, usually concentrated on high-end models, built to satisfy the country gentleman seeking refined space and practicality, especially if a hunt came along, so the cars became known as the Shooting Brakes. Cars like many a Bentley or Rolls special-built estates (another typical British term), were good representatives of the lot, but soon the concept became a thing to be proposed officially by mainstream marques also, with one of the most famous British woodies being the cute, famous Morris Minor Traveler, which set a trademark soon to be followed, at least in style, by its smaller brother, the Mini Countryman. Other notable “stock” woodies also could be found in the Austin and Nuffield ranges in those late Forties, early Fifties years, and thanks to this vitality the concept gained a typical Anglo-American aura. Ford, quite obviously, and Standard too offered woodies, but as a whole practically every British automaker (Alvis, Lea-Francis et al) supplied woody wagons, whether they were officially marketed by the dealers network or built on special order by some external coachbuilder. Elsewhere in Europe, other car makers had something similar, and among others, a brilliant French example are the beautifully proportioned Peugeots Breaks. Also Germany had some remarkable examples of this style - the DKW and IFA-based compact woodies, while beyond the Iron Curtain also Skoda and, most famously, Moskvitch, proposed wooden-built wagons in their range.

In Italy the phenomenon was, initially, strictly the results of coachbuilders' efforts and one of the most renowned was Viotti, famously remembered for the plethora of wagons with wooden bodies produced for practically all the chassis and drivetrains then available from Italian car manufacturers. One of his most peculiar and remarkable efforts was the Lancia Aurelia Giardinetta (“giardinetta” means Little Garden in Italian and it was an original Viotti trademark, which was created with the evident purpose of linking the idea of the wooden bodies with the typical open-air activities usually connected in those days with the wagon concept), which was officially listed in the same Lancia lineup. Similarly graceful Viotti-bodied cars were offered with the Fiat 1400/1900 mechanicals, while the most common chassis/drivetrain combo was usually the one offered using the Fiat 1100-derived underpins.

The phenomenon slowly began to catch on, but it was decidedly in its infancy: Wagons were always one-offs or limited edition specials, costing much more than the more common sedans, and always linked to luxury. But in the early postwar days Fiat itself found the wagon, and considering the times the woodie, as a most viable alternative to offer the internal roominess so blatantly reclaimed by the potential buyers of its most economical car, the diminutive 500, or Mickey Mouse. In 1948, the Topolino B debuted with a new OHV engine and, most important, a new four-seater model, the Giardiniera (so called because of the resonance with the Giardinetta term invented by Viotti, but different in spelling so to avoid legal issues), which was among the cutest and smallest woodies of all times. The Topolino itself finally began to attract the attention of serious buyers, thanks to the fact of having also a proper four adult-sized seats model (the original sedan was a two-passenger cars, with room good for luggage or, unofficially, a pair of children in the rear interior portion), and when the 500 C debuted in 1949, with a simple yet effective restyling, clearly also the Giardiniera benefited from it. The 500 C sedan was a nice example of heavily American-influenced car in itself, considering that the new body had many contact points with the typical business coupes seen during the Forties in all the American automakers ranges, and before the 1400 debut also other Fiat cars (the 1100 E and the last 6C 1500) offered longer tail ends that were direct imitation of the classic 1940-’48 trunks seen on Detroit products. That was the fashion of the times, as I already said many times.

Coming back to the wagon subject, it soon became clear that the all-steel wagon was the wave of the future, but thanks also to the knowledge of American body techniques used in the 1400 experiences and developments, finally in 1951 the Giardiniera could nicely conform to the new trend. What’s the reason to include this story among these pages? Only because during its time the 500 Topolino took distinctive American looks? Only because there was first a woodie and then an all-steel bodied wagon? If so, the rest of this writing should take a look at practically every single Italian car from the last 100 or so years, because things like the closed sedan, the hardtop coupè, the V-12 engine and so on can be as a whole nicely linked to American experiences. No, the fact that the 500 C Topolino Giardiniera Metallica is here is because Fiat designers chose to maintain a close visual connection with the previous wooden flanks, and so they opted to do exactly what Willys and Crosley had done with their all-metal wagons: use stamped indentations on doors and rear quarters, and rear door, usually painted in contrasting colors than the rest of the body. Fiat chose to do this at precisely the time that was seeing an upsurge of the Plymouth Suburban, which sported flat sides that were arguably easier to build. However, imitating the Willys or the Crosley is not so strange, considering the fact that Fiat was also offering all-metal closed 500 C vans and so, to avoid the risk to make one of its bestsellers look like a commercial vehicle, with all the image-consciousness problems eventually linked to this, executives and designers chose to again continue the woody look, although with stamped metal rather than with tacked-on panels. The effect is still good today, and despite the fact that the 500 B and C done in wood are incredibly valued and attractive, the 500 C metal wagon has a class and a cuteness of its own. Later, the experience gained with the 500 Giardiniera helped Fiat to become the quintessential Italian wagons specialist, with many nice designs and sometimes with true masterpieces. Considering that it all started from so little acorns… quite an achievement indeed.

Dreamboats

Sometimes I had some sort of déjà-vu while taking a look at some of those magnificent Motorama two-seater convertibles, and at last I understood why. It’s because when I was a child one of my favorite toys was a magnificent 1/18-scale model of the Pinin Farina-designed Lancia Aurelia B24 Spider America, the first edition with the wraparound windshield. Now I am intrigued at how similar looking some solutions appear on both the Italian car and such masterpieces like the Buick XP-300 and Wildcat I, the Oldsmobile Starfire and the Chevrolet Corvette. One can always say that it’s impossible to compare them directly, and in effect the sublime lines of them all are quite different, but just like some of those two-seater sportscars, the Lancia was the foremost example of those PF-designed spiders where the interior is almost exactly centered between the front and rear wheels, yet looking still so sporty (the following Giulietta Spiders, Alfa spiders, and Fiat 1200/1500 and the Tom Tjaarda-penned 124 Spiders all followed this ideal). Sure, those proportions aren’t a Corvette peculiarity, but their purity of lines surely was, with the Motorama Corvette always being a stunner expressly because it avoided an excessive use of flamboyant details.

Clearly, at least another American car comes to mind when taking a look at the sublime lines of an Aurelia B24: the second generation Nash-Healey, which offered inspiration for the Lancia’ rear end features. However, this is quite obvious because both were designed under the same aegis, and by the same hands. It is remarkable instead to see that the simple concepts behind the Aurelia B24s and the Nash-Healey can also be found in the original Motorama Corvette, and the adoption of the Aurelia’s wraparound windshield was surely a touch influenced by the Plastic Fantastic: same roadster concepts, same purity of lines, same simplicity of front and rear ends concepts, (albeit the Lancia, the Nash-Healey and the Chevrolet couldn’t have more different personalities than in this case), same neat intimate interiors, done in the purest roadster spirit, with no concessions to such luxury like winding down side windows (in the case of the ‘Vette, it was sort of “homage” to the typical European sportscar purity). Also intriguing is the fact that all these cars (the Nash, the ‘Vette and the B24) had six-cylinder powerplants. The Aurelia B24 debuted at the Bruxelles Salon in January 1955, but for almost half the 1954 the prototype, which was even more essential (it did have simple bumper guards directly applied to the body, and not the “gullwing” bars of the production version), was seen in Turin while was driven by Gianni Lancia himself, son of Vincenzo and then head of his namesake marque. It is always important to say that among all those cars designed by PF and following his early B24 Spider America there are also a number of gorgeous Ferraris, and at least one of those Maranello jewels was a convertible with proportions quite alike the early Corvette: the 250 Cabriolet, the one with the “sore thumb” taillights…was it only coincidence? Or the exquisite proportions of the ’53-’55 ‘Vette were spectacular enough to be used as an ideal reference while working to shape that exquisite sculpture on wheels? Maybe not, after all, the frames furnished by Enzo gave quite perfect proportions by default, and the European fashion was still relying on the long hood-short deck mode for the perfect sportscar, yet I’d like to think that Pinin Farina and his staff were very, very conscious about the ultimate American sportscars efforts. More than anything else, this is another demonstration that Pinin Farina was always fast to pick some of the best ideas of the motordom industry, and then he and his staff had the capacity to use them and transform them in personal and unforgettable masterpieces. Only the greatest can achieve this with nobody lamenting the fact to have been blatantly copied.

P.S. Before any objection can be made, I’ll write something about that quite obvious Yankee touch that became the epitome of the Ferrari’s rear end for something like twenty years: yes, the twin circular taillights, so familiar with any owner of a ‘Vette since 1961 and Corvairs, and with a zillion Impalas, Caprices, Bel Airs, and Biscayne drivers. In reality, this is only to show that Pinin Farina, (and who else ?), when presented a good opportunity set immediately in motion to make it being an even more original and maybe better result. The dual circular taillights appearing on the Dinos (also the Fiat Dino Spider) then on the Ferrari regular production models, have perfect proportions, something not always possible to say about the early rendition of them on Corvette. It is mainly a matter of taste, but Chevrolet itself corrected this giving quite the right proportions to them with the C3 Corvette, in my opinion those seen earlier were only a tad too little, or maybe the chrome ring around them was too much evident. Since day one, instead, those on the Italian cars look right, not too small, not too big, with no chrome decorative moldings. So, if Chevrolet had reasons for using them, and to the point that ‘Vette and full size Chevrolets in the Sixties became almost synonymous of circular taillights (with many a domestic competitor sometimes resorting to them also), why can't the same be applied to Ferraris? Once again PF showed that there can always be a way to improve already good ideas coming from someone else.

Bywords: Nash, Florida, Motorama. Guess Who?

Did I already say that the really greatest automotive talents were always the ones able to take cues from here or there and being able to translate them in novel and almost magical concepts for their costumers? Yeah, I did exactly that only a few words before, but there is no denying that when the name of the designer is Pinin Farina (and his magical staff) there is some perplexity about the simple thought of seeing them “inspired” by others’ ideas. I’ve just written about the wise use PF did of twin round taillights, but even more tangible examples could be found in the Cisitalia 202, or in the Aurelia B20 GT (which connoisseurs say it was at first penned by Boano, and initially built by Ghia working together with Viotti, but surely without the decisive PF contribution in its further development and production maybe story would be different as far as the fate of this car is concerned) but I will not tell anything about them, they are almost mystical concepts of design. As I will explain, I‘ll leave to everyone’s mind the possibility to think about the similarities of those cars with other existing models. Instead I want now to write something about the fabulous series of Lancia Aurelia- based Floridas, which became the very cars on which the Lancia Flaminia sedan and coupé were based.

Taking a look at the first two of the series, it is undeniable that a certain American car comes to mind, a marquee that was a truly good client for Pinin Farina, and always ready to use his renowned badge to glorify their cars, which for a good 80 percent were styled in-house; sure, I am talking about the Nash, and while the second generation Nash-Healey was practically a total design by Turinese equipe, the same cannot be said about the ’55 Nashes, which continued to wear trademark features of PF like the inverted C-pillar, but now also sported the utterly peculiar front end for which they became famous, a grille reminiscent of the one sported by the Nash-Healey, but clearly much heavier, much larger, much more American. However, when PF designed the early Floridas, the chosen theme for the grille, headlights and parking lights rendition - and position - was conceptually identical to the one implemented on the bathtub from Kenosha. The result was much more striking, courtesy of much more sporty and spectacular proportions, yet in all the automotive world of the time there were only two mass-produced cars wearing such items, and those ones were the Statesman and the Ambassador (and the last remaining Healey, of course). The Florida also sported a wraparound windshield (of course...after all in 1955 the Nash and the Hudson full-size had the largest front piece of glass in the entire world), and quiet, original fins. In all, however, it is a stunning design, even more beautiful than the PF-designed big Nash prototype also seen in 1955 (and what a marvelous full size Nash could’ve become, if the same lines of this intriguing one-off could have been brought to a production line!).

What set apart the Florida’s four doors is the way they opened, a trait looking very much like if the doors themselves were taken off a quartet of Motorama concept cars. But wait! Pinin Farina taking a look at Motorama cars once again? Well, why not? In this case, the cars to look at could have been the ’54 Pontiac Strato-Streak, the ’55 Cadillac Eldorado Brougham and the ’55 Chevrolet Biscayne, and the ’55 LaSalle II. However, Lancia was well known for offering standard cars with such a feature (since the Augusta of 23 years before!), albeit not in a hardtop formula. So, that could be more a coincidence, or only the desire to use a trademark Lancia feature in the boldest possible form, at the time incarnated in the itinerant GM Show cars' pillarless doors ( and the general infatuation for pillarless four doors , it is sufficient to consider the immense success of the four-door B-body Buick Rivieras and their Oldsmobile cousins in 1955).

As a witness of the grandiosity reached by the PF staff, I need to add that another one of the original quartet of cars to bear the name Florida, the last one, called Florida II, would also worked in later years as a possible, if not as the closest inspiration for a certain luxury hardtop which would become one of the most coveted American design of all the era (just like another PF- bodied Lancia could have done as early as 1951 for being an inspirational tool for another American automotive masterpiece). But here I am talking about the American “influence” on Italian design, and this is still tangible in even a masterpiece of masterpieces like the Lancia Floridas (and relative standard Flaminia too), although here Pinin Farina simply put to good use many ideas of his own given earlier to Nash, and many familiar traits of Lancia. That Harley Earl’s staff was doing the same is likely more an “award" given to the boldness of the door opening system of the Lancia rather than anything more, and this is a real achievement for Lancia too. After all, Harley Earl was another genius, if not The Genius, and so he knew when a really intriguing idea deserved to be exploited. And at the time, Lancias were full of bold ideas.

Of Downtown And Roman Roads : The Metropolitan And The Appia Coupé

As we’ve seen, Lancia wasn’t immune to sometimes sport on some of its models interesting styling details already seen, albeit in different proportions, on American cars; this time, in 1957, a little Anglo-American two/three-seater would be a worthy inspirational tool for the elegant Appia Coupé, one of many variants seen on the versatile platform of the mid-to-low priced car which had debuted in 1953 and had the name derived from a famous Roman Empire road. In 1956 an effective redesign by Piero Castagnero transformed the somewhat dull first-series sedan in a downright elegant car. The following year, the Pinin Farina-designed, Viotti-built club coupé entered the market, made its market debut, alongside the Convertible, this one proposed by Vignale.

They were regular production models, and not special one-offs variants, but while the convertible sported a sober Italian look, the PF model had some features similar to what the renowned coachbuilder had suggested to Nash. The simple grille treatment, resembling the one seen on the production Flaminia, looked like it could belong to a small Nash, and even more intriguing was the peculiar roof rear pillar shape, quite like the one seen since day one on the Metropolitan. At the time Nashes were usually conceived by in-house Nash styling staff directed by Ed Anderson with “suggestions” made by PF. In the case of the ’52 Airflytes, the C-pillar and the grille seem like the only elements to bear a marked PF imprinting, and so I don’t find so strange that PF “recycled” here and there features seen on cars of other marques. After all, that’s what other stylists did and always have done, just think about Michelotti and some of his creations’ rear ends in the Sixties: the Daf 33, the Triumph 1300s and the Ford Anglia Torino are all declined from the same theme. So, even a grand name like PF did similar experiences, and the radical V-shaped pillar adapted quite well to the sporty-yet elegant-yet compact new Lancia.

Interesting to notice that when PF started to work together with Nash, the NXI, soon to be NKI, soon to be Metropolitan, was already been seen in a near-to-production shape as early as 1950, and it is well known that the initial car was proposed by Bill Flajole and built with Fiat 500 Mickey Mouse mechanicals. What’s more, before becoming an Austin-powered and Austin-built car, the same Fiat was approached by Nash execs to see if they could build the car for them, but the same reason that put the Fiat 1400 out of the American market also worked against a Fiat-built Met. At the time, the ratio between dollar and pound was much more favorable to the the former, and so the decision to build the car in cooperation with Austin soon became a reality. In the Flajole’s prototype also the original V-shaped roof treatment was close to the definitive model, in itself a clear “homage” to early hardtops pillars, so, regarding the Appia’s roof, I could almost dare to say that PF didn’t invent anything, and simply thought too good to be left apart such a striking concept because it could nicely work on a car like the new Appia – as indeed it did. Of course, maybe some Lancia execs liked what they saw on the Met, and asked PF to act consequently. What’s more, one can always say that Pinin Farina back then worked together with many marques, and he was free to choose whatever idea he thought good to be proposed to his clientele, even ideas already “offered” elsewhere. Regardless of this, the similarity is there to be seen, and in both cases that inverted trapezoidal shape, much more radical on the Lancia though, is one of the most distinguishing feature of both cars. Another case of a good idea working well for two very distinct –yet closer than expected cars, and something to make us car fans thinking even nastier things about today’s car design and badge engineering, when totally unrelated cars look invariably alike, despite not having a single screw in common.

Make sure to check back next week for part 2 of this examination of parallels and influences among American and Italian automotive designs.

Wagons are arguably the most practical form of transportation. By extending the relatively low roofline of its sedan counterpart, wagons offer plenty of precious cargo space while still retaining a lower center of gravity for zippy handling and spirited driving whenever the urge may hit. Despite all the fun that can be had in a wagon, massive high-riding SUVs and Crossovers have taken over the modern-day automotive market.

The SUV trend is unstoppable and new wagon models are becoming scarcer as years pass. Back in 1975, sedans and wagons dominated nearly 80-percent of the U.S. vehicle market. More recently, new SUV and truck sales have climbed to around 80-percent since 2011, taking the place of smaller sedans and their longroof model varieties.

In the classic car market, wagons are rapidly gaining popularity. Like the old saying goes, “They don’t make them like they used to.” Classic wagons exude a style that isn’t seen in today’s automobiles and car enthusiasts are gobbling them up like candy. Here are 15 examples of what is available in the classic wagon market today.

Everybody loves a classic woodie wagon! This two-door 1951 Ford Country Squire wagon still sports its original wood paneling, not that fake plasticky stuff seen on the more modern “wood” wagons. The seller states it is a fresh build that has only been driven 500 miles. A 350-cid Chevy Vortec Engine is hidden under the hood. Tasteful modifications include a Fatman Fabrications front end, an 8.8-inch rear end, power steering, four-wheel power disc brakes, and an all-new interior.

As stated in the auction listing, here’s a family hauler that would draw envious glances from Clark Griswold, this 1979 Chevrolet Caprice Classic Station Wagon is believed to be in original condition apart from maintenance and service requirements, according to the selling dealer, who acquired the woodgrain-trimmed wagon through an estate sale. There’s a 350 V8 under the hood and the seller notes service within the past few thousand miles has included new brakes, a new water pump and radiator, valve cover gasket, muffler, and more. Click here to see the full auction details.

“Experience the epitome of vintage charm and modern performance with the 1964 Mercury Colony Park, a California wagon that's been meticulously restored and upgraded to perfection. Underneath its classic blue exterior adorned with wood paneling lies a beastly 390-cid V8 engine, now equipped with a Holley Sniper EFI system for improved fuel efficiency and smoother power delivery. Paired with an automatic transmission, this wagon delivers a driving experience that's as effortless as it is exhilarating.”

This beautiful Brookwood underwent a professional frame-off custom restoration. It’s a restomod of sorts, still sporting its classic looks while implanting some modern creature comforts and technologies. It’s powered by a 480 horsepower LS3 engine paired with a six-speed manual transmission, for starters. Cruise to the classified to see more photos, plus the full list of custom goodies included in this immaculate 1959 Chevrolet Brookwood Nomad.

You’ll be hard-pressed to find a classic wagon exactly like this one-of-a-kind 1964 Chevrolet Chevy II Nova. Described as a mild restomod, this station wagon has just 1,000 miles accumulated since its frame-off restoration. The seller states that everything has been done on this car and it “rides, drives, and handles way better than you would expect; straight down the road with no shimmies, shakes, or vibrations.” The craftmanship on this V8-powered Chevy wagon is described as “simply spectacular.”

Volvo wagons are getting hard to come by, especially the 1960s-era cars. The seller states that this two-owner, mostly original 1963 Volvo 122S B22 was used as a daily commuter until a few years ago, has been regularly serviced, and is in good running condition with a recent fuel system overhaul. The original exterior does have some blemishes and surface rust, but the seller assures that “With a fresh paint job, she would really turn heads!”

“There are refurbishments and restorations, and then there’s the kind of treatment this 1953 Willys Station Wagon has received. The work is described as a minutely detailed body-off restoration that has left the wagon in better-than-factory condition. Among the many non-production upgrades said to have been performed on this Willys are heated leather seats, a lamb’s wool headliner, a Pioneer audio system with Bluetooth capability, map lighting, and USB charging ports. The Willys is reported to have a replacement F-head engine of the same year and displacement, now rebuilt, and the wagon is described by the seller as free of rust.”

A muscle car in wagon form is what dreams are made of, especially when talking about the second-generation Chevrolet Chevelle SS. This example, a Placer Gold 1971 Chevrolet Chevelle SS Wagon, gets its power from a rebuilt 402 cubic-inch V8 producing 350 horsepower paired with a T-10 4-speed manual transmission geared with a 10-bolt rear end, plus other great features.

The sky roof (or panoramic roof) on this 1967 Buick Sport Wagon GS adds to this classic car’s luxurious feel. The seller states it is powered by a 350 cubic-inch small-block topped with four-barrel carbs and a Star Wars-style air cleaner. The wagon is described as rust free and ready to drive.

According to the seller of this custom 1956 Ford Parklane Two-Door Wagon, it is so clean that you can “eat off the door jams and spare tire well.” The mild custom sports a 312 cubic-inch V8 paired with an automatic transmission, plus loads of other goodies, including a custom interior. Take a close look at the photos supplied in the Hemmings Marketplace classified listing.

This extremely rare wagon is just one of only three examples produced, and the seller confirms that they do have the production records as proof. Previously owned and restored by the founder of the AMC club of America, the 1959 Rambler American Deliveryman Panel underwent what is described as an exceptional nut and bolt rotisserie restoration just a few years ago. It’s powered by an inline-six engine backed by a three-speed manual transmission, and the engine bay, among other details, is described as stunning.

The classic Chevrolet Bel Air embodies the American Dream of the late-50s, and its V8 engine signifies the era of American muscle. This elegant wagon is offered with an automatic transmission for easy cruising. The seller also states that the 1957 Chevrolet Bel Air is equipped with air conditioning, its classic AM radio, power brakes, and power steering.

If you’re searching for a wagon that will stop passersby in their tracks, look no further than this flame-adorned 1950 Oldsmobile. Under the hood you’ll find a powerful 5.7L Vortec 350 cubic-inch V8 paired with a smooth-shifting four-speed automatic transmission. The seller states, “this Oldsmobile Wagon is not just about looks and performance, it’s also equipped with a range of features designed to enhance your driving experience.” Get the full details here.

This unrestored 1959 Plymouth wagon shows 78,800 original miles on the odometer. The 318 polyhead Mopar engine is topped with a Holly two-barrel carburetor and exhales through a dual exhaust system. Don’t let the main photo of this beautiful machine on a trailer fool you: The seller states that the car is in survivor condition and it drives without issues. Check it out.

This two-door, six-passenger, V8-powered 1958 Edsel Roundup wagon is described by the seller as a no expense spared custom. The customizations were completed by its owner, Frank Montelone, alongside his long-time friend, the legendary George Barris of Barris Kustoms, which makes this custom wagon an incredibly rare find.

There are more wild wagons where these came from. As of this writing, there are around 50 classic wagon listings on Hemmings Marketplace. Take a look!

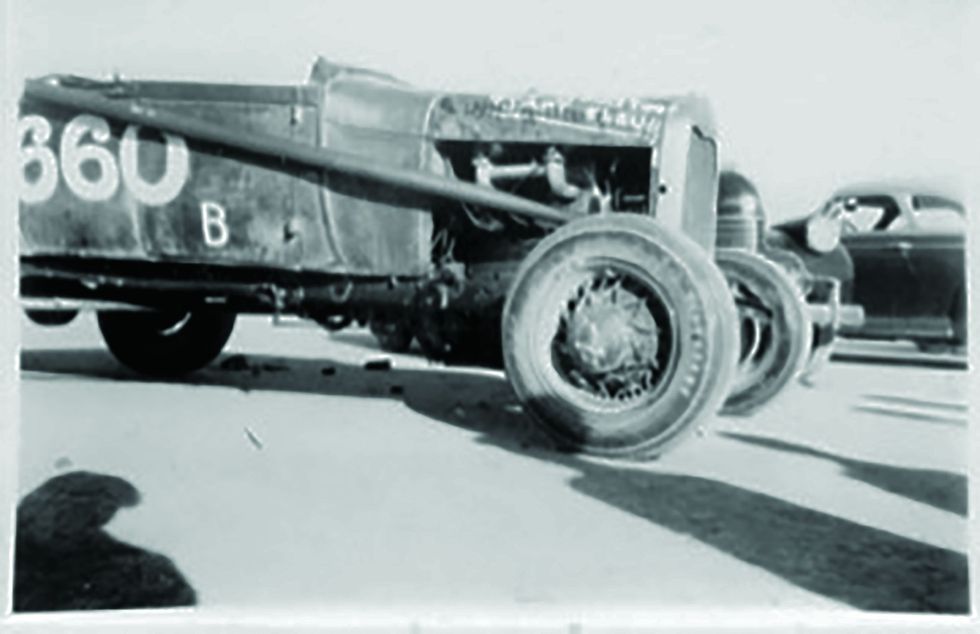

Ray pile was a part of the immediate post-World War II generation of hot rodders. During the war, he was a waist gunner in Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers attacking Nazi-occupied Europe and afterward he returned to his home in Southgate, California. This is his car, the Pyle Special. Not much is known about its life before Ray got ahold of the Ford. It was just one of millions of Ford Model A’s produced for 1928-’31.

Just two years after the end of the war, an uncle got him set up running a gas station. That’s when the roadster comes on the scene, and with it, Ken Eichert, the father of current owner Chris Eichert and son of Ray’s benefactor-uncle.

Image courtesy of Chris Eichert

A mild-mannered, full-fendered roadster most of the time, one weekend each month the Pyle Special would transform into a race car bent on going as fast as possible on the dry lake beds northwest of Los Angeles.

“Ray was my dad’s cousin on my grandmother’s side,” Chris says. Ken had survived a bout with polio earlier in life and was prevented from participating in most sports because of a bad leg. He discovered an outlet in the machines found at his older cousin’s shop and as an honorary member of his car club, the Gaters (note the intentional misspelling as a nod to Southgate).

“My dad was very active with Ray’s roadster. He tore it apart, worked on it, took off the fenders and installed the bomber seat for Ray to race on race day. From 1947 to 1949, Ray was going to the dry lakes with the Gaters, and the roadster was actually a dual-purpose vehicle: it ran full fendered on the street and was Ray’s get-around car, his family car, and then he would race it every month when they had a meet.”

The late hot rod historian Don Montgomery was adamant that the immediate post-World War II years represented the only pure expression of the hot rod: a true street/strip car that was driven by its owner/builder for transportation Monday through Friday and was stripped for racing on the weekends. Postwar racing for hot rods in Southern California circa 1946-’52 was largely either “the lakes”—meaning the dry lakes of the Mojave Desert, mostly El Mirage, or drag racing. At the tail end of the period, drag racing started to become formalized, on closed strips often comprised of aircraft runway infrastructure built for the war. Before that, acceleration contests were an informal activity done on public roads and facilitated by the popularity of drive-in restaurants.

Photo by Todd Ryden

This is the engine Ray raced at Santa Ana, originally built for him by Cook’s Machine Shop. Chris says it’s been drilled for full-pressure oiling, has had large valves installed, and had an unmarked but “really big” camshaft installed. It has since had fresh pistons and a milder cam installed. The Stromberg 81 carburetors are a smaller version of the 97, originally intended to equip 1937-’40 Ford 60-hp V-8 engines.

That three-faceted nature of postwar hot rods made them special and keeps them relatable today. Most roads in America are still suitable habitat for 1940s cars—whether they were new cars from 1947 or have been updated to 1940s technology. That ‘40s technology makes for a particularly satisfying operator experience—just automated enough not to be intimidating, but satisfyingly mechanical and interactive in all other respects. The sights, sounds, and smells are pure automobile, and the industrial design of every component says, “built right.”

Small wonder Chris decided to take the roadster back to how Ray had it. It even does a lot to explain why Chris’s father bought it off Ray in the mid-1960s, over a dozen years after it was last raced. It was far out of step with those times. It didn’t even have a flathead V-8. Ray had built the car to use four-cylinder power and its final engine had been a Model B unit, the 1932-’34 successor to the Model A four-cylinder and incorporating many of the popular modifications already done to make Model A engines suitable for high-performance applications.

“The motor that Ray raced with at the dry lakes was a four-banger with a two-port Riley,” Chris says. The Riley was an F-head design, or what the British and Harley-Davidson enthusiasts call “intake over exhaust,” meaning the exhaust valves retain their stock location in the block, but the intake valves are relocated overhead and actuated by pushrods and rocker arms. Even in flathead form, Model A and B four cylinders were respected for their off-the-line performance while the Ford V-8 was capable of greater top-end speed. An OHV or F-head conversion on a four-cylinder usually meant it was capable of keeping up with a flathead V-8 even at those higher RPMs. Chris would love to someday replicate that engine, which he and Ken discovered in derelict condition shortly after Ray’s death in 1987 and deemed unsalvagable.

The roadster’s final outings were to what was then Santa Ana airport. The first modern dragstrip began operation there in the spring of 1950 and Ray quit driving the Pyle Special about 1951. It didn’t move again until 1964 or ’65, when Ray sold it to Ken, who in turn held onto the car more as a keepsake than an active project. As a child, Chris would sneak into the freestanding garage where it was stored and sit in it and later it would provide plenty of father/son bench racing and swap-meet parts buying episodes.

Aside from one brief-but-memorable ride, the car sat in storage until 2007. By that point, it had suffered a couple indignities: its engine sold off to a friend’s speedster project and one fender and splash apron were brutally disfigured in a freak accident involving a large stack of tile.

“My dad was getting older. I told him I wanted to get the roadster going and he told me to bring it over. I took it completely apart and I cleaned off decades and decades of dirt. I actually saved some of it, thinking it was probably El Mirage dirt. I have two cigar vials full.”

That cleaning and disassembly venture was a crash course in postwar-era hot rodding.

Photo by Todd Ryden

The front axle was dropped back in the 1940s and installed on the roadster circa 1950. To further lower the roadster, the spring eyes were reversed on both the front spring and in the rear.

“Nothing was precisely done. It was a real trip to see what hot rodders did back then and how they put stuff together. It truly was like going back all those years. Then seeing how it evolved in the late ‘40s into the ‘50s in old pictures, as it became what it is today.

“I ended up buying the motor back from the friend with the speedster. I told him what we were going to do, and he did not hesitate to sell it back to us. I had a friend of my dad’s rebuild the motor.”

Chris then re-installed all the speed parts that had come from Ray, plus a few his father had collected along the way, notably twin Stromberg 97 two-barrel carburetors on an Evans intake and a Mallory dual-point distributor. Chris also discarded Ray’s rear-only mechanical brake setup for 1939 Ford hydraulic brakes contributed by a friend of his father. “That’s the kind of friends my dad had,” he says. “All his hot rod friends knew about the roadster and when I told them I was working on it, they gave him stuff.”

Once the roadster was going, there followed a whirlwind of father-son activity with it, culminating in the twin delights of a Hot Rod Magazine feature story of the still-in-primer roadster, and Ken getting to drive the roadster at El Mirage for the first time ever. Then, Ken died in 2011 and the roadster took another hiatus.

“After Dad died, it sat. I could not get the motor running for snot. I took it to three or four old guys who worked on old Model A’s, hot rod guys, they couldn’t get it running. I kept spending money to no result, so I mothballed it for another 10 or 12 years, from 2011 to about a year or so ago.”

Photo by Todd Ryden

“It’s a rattle can, but the coolest rattle can you could ever be in. I still drive it and have memories of my dad and wish he were there and could share the moments. Even though I didn’t know Ray, I think of him. He got this up to 116 mph and that’s a feat. I’ve probably gone no faster than 65 mph and it scared me, I couldn’t imagine doing 116.”

For help, Chris turned to a fellow member of the revived Gaters club, welder/fabricator and hardcore enthusiast of midcentury Americana, Randy Pierson.

“He’s got a period army tent, a period camp stove, he tows his roadster with a ’49 Merc four-door. The body on his roadster is all handmade. He is the pinnacle for our group who keeps us true to that era and what we do and what we don’t do and what we put our signature on as a club as far as being period correct.

“He did some body work (but he said it was one of the nicest Model A bodies he’d ever worked on). It was all hand welded, hand hammered, hand finished. We stripped off down to the color that was consistently across most of the body. He rewired it with cloth wire as it would it have been in period, and he really was meticulous to getting it back to as it was in 1947. We looked at pictures. He kept what he could keep and mimicked what needed to be done to make it true to its 1940s life.”

Also mimicking its 1940s life was the scramble to get it ready for race day. In this case, the West Coast iteration of The Race of Gentlemen, which is not a beach race but is instead held at Flabob Airport in Riverside, California, in the style of the original Santa Ana drags.

Although it still rides on a Model A frame, at some point the k-shaped crossmember from a 1932 Ford was installed, which stiffens the chassis slightly and provides built in mounts for the later transmission and floor pedals. Ray apparently lacked the tools to shorten the driveshaft, however, which pushed the engine and transmission forward slightly. During the rebuild, Chris and Randy moved the radiator back to its stock position to run an original-style hood.

Photo by Todd Ryden

“We found a bomber seat and just a couple weeks before the race, Randy had started to work on the motor to get it running and he too could not get it running right. He pulled it apart and he’s not a motor guy, but he knows enough, and one of his neighbors is an old hot rodders. We changed out the 97s to 81s because the 97s were a lot of carburetor for that little banger motor, especially in duals. Then he still had a hard time. We took out the cam, put in adjustable lifters, and at the very last second, we were trying to find a different cam for it, because we figured there was something going on with the cam. I asked a buddy if he had anything to go in my roadster and he sold me a cam and I sent all that up to Randy, who worked on it feverishly for a week to ship it back down for the races. He got it running and when he got to drive it down the street, he was surprised. ‘This thing has got it. This thing scoots.’ It runs really strong.”

That strong running paid off in a lot of fun at TROG West, giving truth to one more of Ken’s old stories.

“My daughter has a video of me racing a T/V-8 and I pass the camera behind the T, but by the time I get to the finish line, I’ve beat her. It brings back memories of my dad telling me ‘Yeah, that motor will beat some V-8’s.’ It’s one of those moments, again, of my dad’s stories from all those years ago having proof in their pudding. Those revelations keep happening.”

What’s next for this old racer? “I never did get it registered when I moved from California to Texas,” Chris says, “but I am going to get it registered.”

Hopefully, it will be back on the streets soon, paying tribute to that triple-threat nature of hot rodding’s golden era.

Photo by Todd Ryden

“We reproduced the tailpipe that’s on it from pictures. It’s built from 1938 driveshaft enclosures because of the taper they have at one end. When Ray was racing it, that’s one of the things my dad put on it every time, so that’s what we did when we were putting it back together. It’s got a killer, throaty sound to it.”