The Italian Influence on American Cars, part 2: turbines, aero, hatchbacks, and fastbacks

02/26/2017

[Editor's Note: Matteo Giacon's second part of this series focuses on some of the sexier links between American and Italian automotive design. For part 1, click here.]

Turbinas, Speed Records And The Beautiful Brute

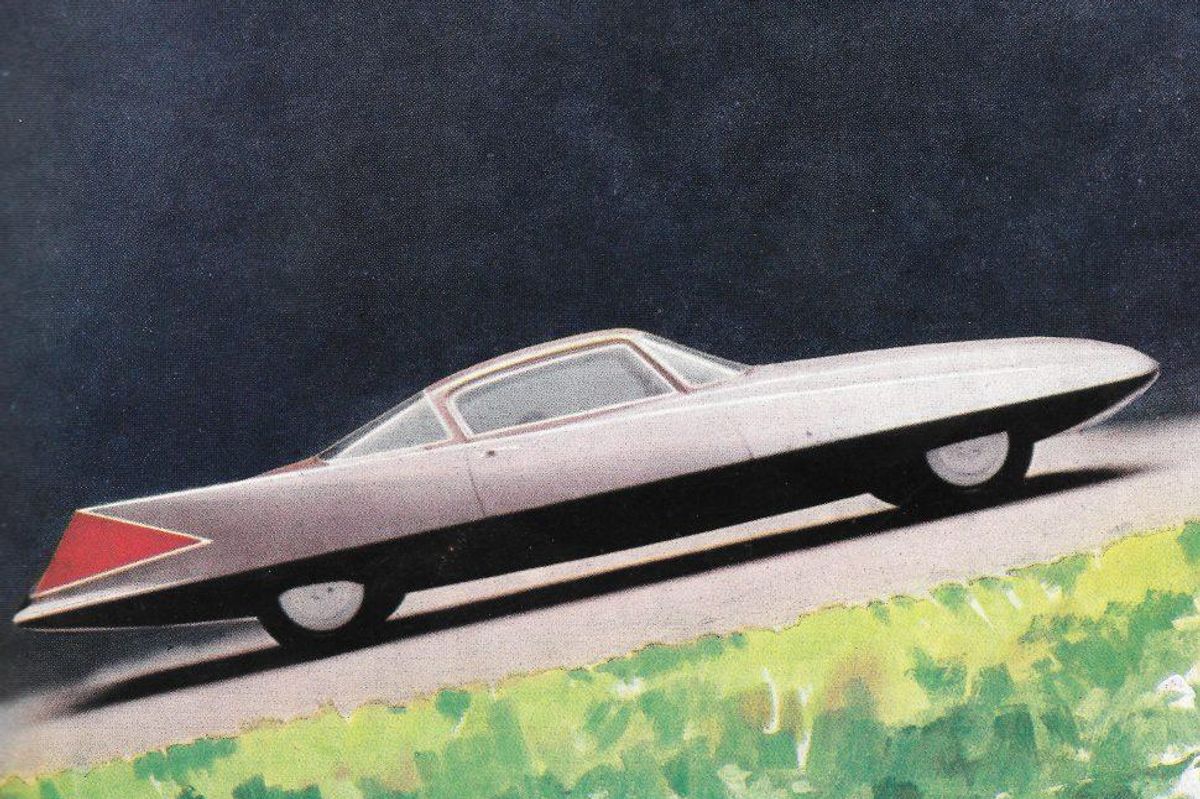

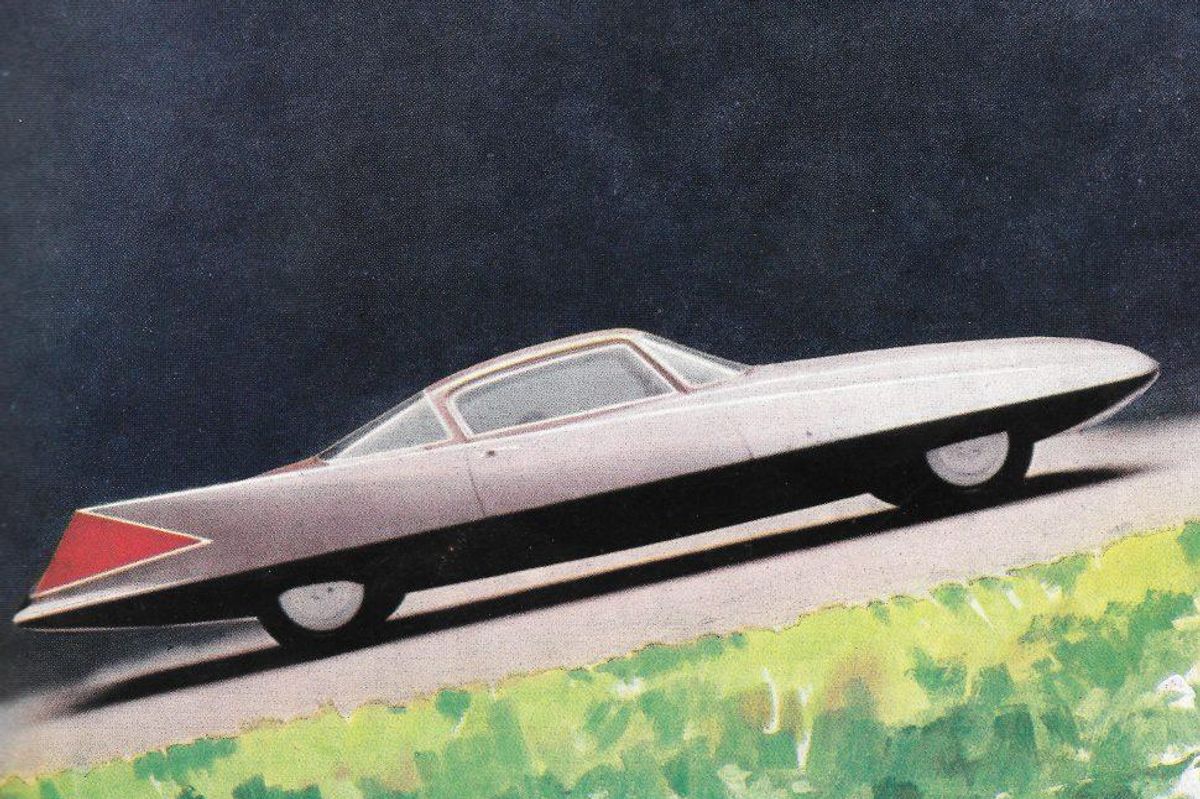

The Fiat Turbina was indeed a most spectacular car, in all likelihood the first proper Fiat concept car and one of the most unforgettable Fifties designs. Luigi Fabio Rapi penned a car bearing many details of his previous ill-fated Isotta Fraschini 8C Monterosa proposals, and the rear fins of both cars look almost interchangeable elements. The final product was a stunning car, also blessed somewhat by its inner mechanical components, starting with the turbine itself, that is, a fact that surely lent Fiat engineers and Rapi to develop a striking shape of most aeronautical flavor, yet decidedly practical and somewhat more simple to build - if the occasion would’ve arrived - than a vast majority of similarly stunning American dream cars.

This car can be considered, from a stylistic point of view, as the Italian answer to the original LeSabre, especially if seen from behind (the two cars could bear the very same badge indeed!), but while the look of the American fins were linked to the Cadillac style, the one used in the Italian car had a look already implemented by Luigi Rapi while developing his already noted Isotta Fraschini designs. And while the LeSabre was, for every onlooker, a sort of MiG that did fall in Michigan and was made streetable (Korea War’s Mikoyan Gurevich 15s were a very nasty surprise for American aviators, and it is curious that the Earl’s dream car ends to conjure up more a notion of the Soviet war machine rather than something more patriotic), the Fiat concept was devised as a sort of airplane with four wheels, sufficiently shaped as to look like a car bearing resemblance to something akin to an average automobile (and it is kind of bigger brethren to the 8V coupé, because the same man, Rapi, was behind it too - although the Fiat 8V wasn’t exactly the most common car an average Italian motorist could be able to drive, even less so to spot it on the road), yet possessing all the virtues of a jet airplane in spades (the engine, the performance, the general feel while piloting it, even the kind of fuel necessary for the turbine - kerosene - all conjured up to give a driver the qualities – or the worries – of a seasoned jet pilot), and being able to offer them in an even more convincing quantity than the LeSabre.

In effect, some of the Turbina’s style elements were already well experimented, to use an euphemism, but that’s not confined to the Isotta-plus-LeSabre stern: After all, what kind of really self-respecting Fifties dream car could still be conceived with suicide doors of the type seen on the Turbina? One can always answer citing the Alfa Romeo B.A.T. 7, the most outrageous of the lot… yet they were there, and they did a commendable job in helping entry and exit of what was intended as a car for the road. As we will understand later, however, the Fiat efforts toward a future made of turbine-powered car was as ill-fated as all the other involved in this fad. Despite this, the result remains what I already described: an astounding machine through and through. The fins are surely the design elements that immediately caught the onlooker's attention and with their towering height it couldn’t be any different (the same thing worked with both Cadillacs and the LeSabre, right?) and the general lines of the cockpit (and rarely a similar definition could be more apt than in the case of this Fiat), albeit not overtly revolutionary, had the surprising - and very practical indeed - touch of the doors being also an important part of the roof lines, very much in tune with the stylistic ideals found on Tuckers and Darrin-penned ’51 Kaisers - or the ones predated by that absolute sculpture that it is the Bugatti Type 57SC Atlantic, maybe the closest to what was seen on the Turbina - but in this regard much more linked with the need to offer a wider entry room for pilot because of a lower structural interference, something akin to the needs that exactly at the same time led Mercedes engineers to devise the gullwing doors for the 300 SL, and for a similar structural reason. In the case of the Fiat, the high lateral sills hosted the two fuel tanks; with de riguer semi-wraparound windshield and full wrapover rear screen, fashioned in a shape familiar to many an Italian Gran Turismo of the time, the car was miles away from the standard-production Fiats.

The front end had an ovoid shape, surrounded by a discreet chrome frame, and the lateral bumpers were nothing more than two thin bars drowned into the metal. These front elements, plus the absence of visual external lights - for what I know, they were hidden in the central oval nacelle itself - and the general aerodynamic roundness of the entire body, also followed the pace set by the 1952 Socema Gregoire, albeit the end result was much more aggressive than the elegantly chiseled French prototype. One can also find hints of Pahnard because of that oval grille, but it was all the rage back then, and it appeared particularly good-looking on a turbine powered car. (As an added note, in 1954 another intriguing turbine car, a convertible, appeared as a fictional vehicle in the pages of the French comics magazine Spirou. The end result is pretty much like a Gregoire with the heavy chrome oval nacelle surround just seen on the PF 200 nose.) In the case of the Fiat Turbina, there were no headlights indeed (the Gregoire had them hidden just like a ’42 DeSoto), but the two “skirts” ahead of the heavily-shaped front fenders that surrounded the wheels gave the idea of hosting lamps below them, in a very interesting interpretation of the hidden headlamps look. In reality, they give access to the twin triple-battery sets necessary for the 24-volt electrics of the car.

The rear portion of the body is undoubtedly the one that most resembles the details then commonly thought to have been on jet fighters. The car had the need to have room for the wide exhausts nacelle, and in this case it resulted in the creation of a large round cavity, mounted in a way it looked like a continuation of the general rear deck shape rather than a tacked-on affair. This is one of the most interesting of the car’s features, a necessity not only because the turbine generated so much hot air, but also because the engine was mounted in the rear, directly behind the cockpit, and it was also of a more primitive generation than the ones being tested in the same years by Rover and Chrysler because it had no built-in device to control acceleration and deceleration, thus there was also a real need to provide the car with perfect weight balancing and superb aerodynamics, to improve stability and road behavior.

In effect, if Fiat's involvement in the study and construction of a turbine car can look far-fetched, it is useful to remember the Fiat aeronautical experiences, almost uninterrupted since WWI, so building a sort of state-of-the-art car for showing Fiat potential was a high priority. High, that is, until Fiat engineers took a closer look at the turbine problems and they concluded they were much too complicated for the eventual benefits, in doing so predating the same conclusions other turbine fanatics came up to (among them Renault with its Etoile Filante, but at least this purpose-built car was intended more for speed records rather than for commercial targets). The beautiful lines resulted in effectively splendid streamlining, with a supposed CD of 0.15, and the fact that Luigi Rapi himself had also designed the frame undoubtedly helped to reach sort of perfection in the way the body mated with the frame. (This was surely not a committee car - it seems that only six men, other than Dante Giacosa and Rapi, were involved in it.) The turbine instead, wasn’t in the way it was initially proposed by Fiat, the kind of device to be put under a car hood: It had no intercooler, so the exhausts were very hot indeed, and the rare road tests it was subjected to (driven by Fiat master test driver Carlo Salamano) showed both room for improvements and the need for the driver to be very careful, thus adopting a kind of drive not exactly suited for the everyday road use. The rear round “hole” incidentally bears a close resemblance to what was proposed on the Motorama Bonneville Special (albeit in the Pontiac’s case, it looked firstly as a spare tire, and secondly it was intended to look as a jet exhaust). But it is clear that what was intended to give only a hint of what could lurk below the hood on the GM experimental or Motorama cars having such an item, on the Fiat it became an essential part of the entire engine assembly, the only way to make it work.

As noticed, the car was built for go, not only for show, but it was quite a formidable feat to be able to cope with the driving problems one did endure while trying his brave soul on this Turin beast, and mainly because of the inner difficult to properly use the turbine itself. Salamano was able to drive it both on the Lingotto pensile test track and then in Turin's more congenial Caselle Airport, where a top speed of 120 miles was attained, using roughly half the available power. Theory has it that the turbine can develop 300 horses with a top speed of 200 miles, provided one could be adventurous enough to try.

However, the Fiat Turbina could remain an episode not directly linked with America, but there is at least a curious stylistic resemblance that has always excited my curiosity. I am talking about the resemblance between the rear of the Turbina and the general lines of the #613, the Chrysler prototype that come closer than many others to be considered as the father of the general lines of the 300 Cs and Ds. The fins of both cars are exactly the same - well, almost, for example there is a chrome molding bisecting the upper and lower portion of it on the Chrysler, and the wheels cutouts are different! And the #613 is wearing an enormous spare tire in almost a vertical position, just what Ex always loved, but also incidentally close to the exhaust nacelle seen on the Turbina (the relatively large dimension of the latter literally pales when likened with the one of the spare tire used effect seen on the Chrysler). All things considered, the use of such kind of fins on Exner’s concepts might be no surprise for many, but the initial idea of their use mainly for aerodynamic purposes seems very much in tune with their initial look, very close the the wind tunnel tested shapes of the Turinese concept (and probably the Ghia-Fiat connection of the time surely could’ve come in handy for Chrysler efforts too). It is also truly important to remember that the Turbina/#613 Prototype fins didn’t remained confined to the mystical world of dream cars: The production 1960-’61 Imperials must be considered as the standard production cars closer to be the ideal bearer of those kind of fins, with the former also complete with a massive taillamp chrome frame encasing the fins' rear edges and, despite being set rearward, very similar in general concept to the ones observed in the Turbina and #613, and the latter following the basic profile lines of those two prototypes. Ok, the dimensions and the proportions are different, but on both there is also the “toilet set” availability - if desired - aka imitation rear spare tire, so is it coincidence only that those two most flamboyant of Exner’s cars at last used such a styling for their rear portions? I don’t think so. On the other hand, the “standard” Chrysler (and DeSoto) fins seen between 1957 and 1959 are rather in the league of those seen on many a Chrsyler/Ghia concept, but also strikingly close to the Savonuzzi ideas regarding those rear appendages. A quick glimpse at the famous Ghia Gilda can be useful.

Back to the Turbina - another interesting fact regarding it is linked with yet another Motorama car. Story has it that the stylists on duty to pen the Oldsmobile Golden Rocket remained very impressed by the Italian effort, and they started with the Italian dream car’s concept of a jetfighter for the open road to envisage their final rendition of this ultimate Oldsmobile dream car (clearly, while designing it, Art Ross used the Italian car as merely an “inspiration,” too many features are unlike, albeit the immortal Sting Ray rear split window, that made its first appearance on a GM car when it was adopted on the Golden Rocket, was a feature already seen on some other Italian concepts of the era, but this is quite another story), so the Turbina surely had an enduring impact. What’s more, it showed once and for all that also an automaker not always linked with in-house grand design could be able to produce something jaw-dropping without too much need to get help from outside or coachbuilders. So let’s give honor to the Turbina (and 8V) creator, Luigi Fabio Rapi, another man that truly deserves to be put among the Immortals Of Design!

Aero Masterpieces

Though this can seem strange, aerodynamic experiences applied to the automotive world are decidedly an ancient science. Thanks to German pioneers with solid and deep roots in aeronautical design (Paul Jaray worked with Zeppelin) or physics and dynamic of fluids (Wunibald Kamm, Rheinhard Koenig-Fachsenfeld, Emil Everling, Karl Schloer among others), by 1930 aerodynamism was attracting more and more attention both because of the fascinating new ideas and shapes then offered following these studies, and because, with the advent of better roads practically everywhere, a higher cruising speed was well within the possibility of all new cars. But the quest to find the best system to maintain it followed two distinct roads. In America, the application of more fluid lines to cars was accompanied by larger engine displacement, studied so they could give effortless performances with little risk of breakage. In Europe, where dimensions and displacements couldn’t compete with the novelties coming from across the Atlantic for geophysical and economical problems, many engineers and designers set to study even more aerodynamic concepts, and in the meanwhile they also tried to reduce weight and to improve the specific output of a given engine, pushing it to the highest possible pre-breakage point. Two different approaches indeed, with some contact points (from an aesthetic point of view, at least), and some remarkable differences, especially regarding the chassis and drivetrains, but practically everybody was moving toward more comfortable and better performing vehicles to be offered to a public already fascinated by the new asphalt and apparently never-ending roads. This was noticeable not only in the United States and Germany, with its vast new road system, but also in Italy, even more remarkable because despite the still negligible number of cars then available, some novel roads (called autostradas) were entirely dedicated to motorized vehicle traffic only. So in Italy too there was a sudden need to improve some automobile features just to guarantee they could cope with the new advanced roads. Those roads were quite few, but stimulating enough. And the aerodynamic science could help somewhat. As we will see, it wasn’t a here today-gone tomorrow phenomenon, because the best efforts happened after WWII. However, some remarkable examples can be seen also as early as 1930.

Aerodynamic cars weren’t, in effect, exactly a novelty for the Italian public, what with remarkable examples being seen as early as 1914. The Alfa 40-60 HP built for the Count Ricotti by Castagna, with its remarkable zeppelin gondola shape is surely the most famous and most renowned of the lot of very early cars loosely inspired by something far different than the square-cut format of the times. Also the already cited ’25 Fiat 509 Delfino, complete with huge tailfin, wears a similarly rounded shape body, at least from the cowl back and in open format (the Alfa Castagna had an entirely closed body, complete with portholes-style windows: so it is easy to also see some sort of inspiration came from submarines, then an interesting novelty for Italy, soon to see important action during WWI). Last, but not least, the most triumphant aerodynamic concepts ever to be seen in Italy before the Seventies came from such remarkable record cars like the various types of Abarths, built by Pinin Farina: the incredible Pinin Farina-built Fiat 600 PF Y and the Pinin Farina X, both with distinctive egg-shaped format, and huge but well integrated fins (in the case of the Y, at least in its early version). The X is also known for its very, very special wheels rhomboidal wheels position, hence the name. Both PF cars, what’s more, owe much to the Morelli M1000, a little known concept with, again, a very wild egg shape and rear fins, and even more interesting, to a Michelotti-designed, Vignale-bodied Abarth 750 Goccia (Goccia means "drop" in Italian, quite an apt name for such an advanced design), offered in 1957. It seems like this kind of concept was all the rage within certain circles back then, I distinctly remember also a Soviet prototype, the 1955 Belka designed by V. Aryamov, with pretty much the same body lines – albeit in this case the front end assembly was much blunter. I could also think that the Italian cars owe something to this Russian car but, considering the role the wind tunnel had during their development, I can also imagine that the results ended to look very similar to each other, just like the computer-devised machines of these last two decades. And few can deny the fact that the original Iso Isetta, soon to become a flop on Italian roads, and the BMW savior on German ones, had a remarkable egg-shaped line that was surely good for beating air resistance: Ask those driving it in the Mille Miglia.

However, the most radical and most outrageous cars of the Italian pursuit of aerodynamic science in the Fifties can be considered, with few doubts, the trio of Alfa Romeo built between 1953 and 1955 and called B.A.T.s, Italian acronym for Berlinetta Aerodinamica Tecnica, (Technical Aerodynamic Sedanette), created in 5, 7 and 9 guise and penned by none other than that unsung hero of Franco Scaglione. The first two, as we know, were the most extreme of the lot, from their split grilles to the skirted wheels all the way through the extreme fins; despite the glamorous lines, the effects were there, for the cars were effectively sensational from a pure aerodynamic perspective. The first two were also interesting because of their lack of the typical Alfa Romeo “scudetto” shaped grille; under the skin of these cars there were the mechanicals of the everyday 1900, complete with the five-speed gearbox, good to propel all of them up to a theoretical top speed of 125 miles per hour. The B.A.T. 5 also used a headlight system close to the one adopted by the same Turbina, with the two headlights close to the central “nose” of the front end. While the general lines can be considered as the logical continuation of a lot of Scaglione’s ideas already seen on the relatively less-known Fiat/Abarth 1500, bodied by Bertone (a car that deserves a chapter of its own), especially if the general proportions and some basic lines (the front end traits, the roof looks, complete with the soon-to-be-used split window, the general approach toward the glass area's and the metal surfaces’ development) are taken in consideration, this glorious lineage of cars taught many things to a whole generation of designers, especially among those ready to further develop the fins concept. Finally something so outrageous could be seen in the metal and appreciated from every angle. Despite the more immediate effect they had on the use, for example, of extreme curved glass surfaces (the windshield especially), there is a good possibility to conclude that what set them apart, or, to be more precise, makes them so evocative, is their use of those outrageous fins.

In effect, once again the fins were used here for the sake of aerodynamic improvements and high speed stability so much coveted for by their advocates. It is always interesting indeed to see how many similarities can be found on cars devoted to the same basic purpose. In the case of the Fiat Turbina, the aeronautical fins were pretty useful, in a way not even those on the 1958 Traveler (a highly modified 300D to run ‘shine, with a “souped-up” engine and some important modifications on suspension too, plus some other “accessories” like a switch to drop gallons of oil on the road just to avoid police cars, all done by its legendary owner Jerry Rushing) could eventually reach: Even the one belonging to the Rapi car came in handy after a certain amount of speed (let’s say 140-150 MPH, out of a theoretically projected 200), so the maximum a 300 Letter Series of sort could hit was also the speed at which the beneficial effects of those rear appendages could just start to be seen. But the fins, as it is evident, weren’t the only aerodynamic shapes blessing the Turinese prototype; in fact, both the front end and the front fenders were penetrating enough, as we’ve seen, and their voluptuously shaped look surely were even more stunning in a world where hoods were still thought to sit higher than fenders. But this Fiat wasn’t the first car to have wraparound fenders of this kind (yes, wrapping around the wheels is exactly what they did, or at least they give this type of illusion), and it wouldn’t be the last (the Abarth record cars testify to this; even a remarkable 1963 Stanguellini-bodied, Moto Guzzi-engined record car, named Colibri, had such remarkable wrapped-around fenders, so much so that this car, equipped with a bantamweight quarter-liter engine cranking out 29 horses was good enough to average more than 100 miles on Monza high-speed ring!). Nor was it alone in the automotive world back then either: The Pontiac Bonneville Special had something quite close in concept, both fore and aft the cockpit, and the entire thing worked fine, and of course the plethora of racing and prototype cars which followed suit is almost endless. However, this feature, the all-enveloping fenders designed as to be very rolled up the same wheels, closely following the contours of the same wheel, being practically molded around it, yet looking not tacked-on, but like a basic continuation of the general lateral view, wasn’t new for the Fifties. I am not talking about the standard pontooned fenders, of course, I am talking about those resembling the ones adopted on the Turbina, and in this respect some Lancia Aprilia Aerodinamicas of the late Thirties show us how advanced aerodynamics and shapes could be, especially if done with racing purposes in mind. The Aprilias in this case looked like stunning ancestors of a styling that only 15 years later would become more common, for in 1938 it was more like the ones used by certain German firms for record purposes, or by some Czech carmakers for rather Art Deco-inspired vehicles (like the little-known Praga Super Piccolo, sort of small-scale Pierce Silver Arrow, with an incredible front end looking like an offspring between a ’38 Graham and a ’39 Checker, and likely the direct forerunner to those incredible Docker Daimlers seen in England after the war, or, remaining in Europe, like some Figoni & Falaschi creations! Interesting also to say that this car debuted before them all!) rather than something proper for a fast road or Grand Touring car.

Well, the famed Adler Rennwagen predates these Aprilias too, and they were also used on roads, but this doesn’t detract from the importance of the Italian cars, because their appearance on Mille Miglia roads soon spawned quite a fad among the most forward-thinking carrozzieri, and also among standard cars (this was the period of the Fiat 508 C Mille Miglia, of the famed Alfa Romeo 8C 2900 Touring expressly bodied for Le Mans, and so on). What is interesting to see is the fact that among these Aprilia features weren’t only the large use of curved glass, or the adoption of a wraparound rear window on one of them (maybe the first ever? Surely it predates GM’s hardtops…), but also the use by one of them of a neat horizontal grille, very close to what Harley Earl was busy to develop and then to install on his Y-Job. In effect, in both cases, the most intriguing feature of these cars was the adoption of a horizontal theme for the front air opening, instead of the obvious variation on the vertical theme (and other Aprilia Aerodinamicas had those “classic” vertical Lancia scudettos, albeit rendered as they almost look like something taken directly off an Airflow), a thing still pretty much rare in those years. It was a trait seen, albeit in a smaller dimension, on the front ends of those famous Adler Rennwagens too, though the ones seen on the Aprilia and on the Y-Job are larger, quite closer to what would be adopted first and foremost by American cars starting in the early Forties. In this case, another rather peculiar Praga Super Piccolo, a sedan bodied in 1936 by Sodomka, wears a stunning horizontal-shaped grille, but apparently it was not so influential as one could initially think, or it is a rebodied example done later. What is sure is that the Super Piccolos in general were among the most forward looking vehicles of the Thirties.

So, after all these facts, it is easy to think that the soon to be ubiquitous horizontal-spread frontal grille was firstly an Italian-American-German-Czech experiment, albeit others too can claim paternity to such a novelty - a potpourri indeed, if all hypothesis are presented. Surely, the impact both the Aprilias and the Y-Job had in their respective countries contributed to put them again at the forefront of pure aerodynamic research, or, in the case of the Y-Job, at the forefront of the soon-to-be-seen-production showing of ideas that were also a neat example of that way to market cars that only American firms, at the time, could afford to do.

As we’ve seen lots of times, Germans and Czechs mainly, but practically everybody interested in auto development back then, had quite advanced aerodynamic cars and prototypes, but once again what became widely available to the public sooner than other efforts was the style decided in Detroit by Harley Earl and his entourage. The fact that Pinin offered a detail quite alike to what would soon become a sort of Great Lakes shores trademark is certainly a zenith for his work and his ability to be always at the forefront of this or that trend. It wouldn’t be the last one, as we know so well.

It must also added that for similar reasons to the ones leading PF to develop such intriguing lines for this kind of Lancia, the Aprilia did lend itself for such aerodynamic creations. In Italy it become one of the favorite platforms to do similar things, used by Touring, Zagato, Viberti and others too. What’s more important, maybe, the Aprilia was the base upon which Ghia made a true masterpiece, when the Giacinto Ghia’s firm was called to create a spider of formidable presence and sober yet gorgeous looks, aptly named Aprilia Gran Sport Spider. This car, in all respect, can be considered as the ancestor of many a stupendous British sports car of the Fifties, thanks to its proportions. And speaking of Zagato and Touring, it is impossible to forget their fantastic models done, respectively, on Lancias and Alfas in the Fifties and Sixties, using curved side windows in the same days when they debuted on the Imperials (sometimes even before them), and the Kamm-type rear end so dear to aerodynamic engineers all the world around (but more than half a century ago it was still a sort of unexplored novelty); also interesting is the fact that Zagato had, among the various designers that worked for him, a certain Luigi Fabio Rapi, at least for one of the first among the second wave of aerodynamic Zagato cars, the Alfa Romeo 1900 SSZ. And the second wave of Zagato’s aero cars is an apt moniker, for the Terrazzano di Rho firm was renowned in the late Forties, early Fifties, for its Panoramica series of cars (but they should deserve a few more words, maybe in the nearby future and for their interesting similarity with a certain American concept car). Or, speaking of Touring, it is impossible to forget its aero efforts, as early as 1934 with the aptly named Alfa 6C 2300 Turismo Soffio Di Satana (Satan’s Breath in Italian), an aerodynamic six-window fastback sedan that both put to good use the latest American tendencies and had an interesting heritage when Standard began to build similarly designed cars named Flying Standards. Of course, Touring would’ve offered even more remarkable cars sporting quite advanced flowing-through lines, but more on this later. Just to make a statement, Touring was the creator of the renowned Alfa Romeo Disco Volantes (Flying Saucer in Italian, named just like the yacht of Ms. Largo in Thunderball), a barchetta-type and a coupé so named because of their advanced lines, so evocative of a sporty, yet out-of-earth car.

Before leaving this chapter, I wish to recall yet another pair of well-known Italian creations, but more because they can be considered remarkable examples of a given fad, and not just because they also had some general ideas soon to be seen on American cars: the 1953 Abarth 205A 1100 Sport by Ghia and the Aurelia-based ‘55 Nardi-Vignale Blue Ray. Both cars were penned by none other than Michelotti. The former used a heavily American-influenced theme (and it couldn’t be anything but, considering the various Virgil Exner creations so similar in style then built by Ghia), but it was done with such a grace, such a purity, that no one can deny it can be considered a nice Italian Style representative, especially because its sober good looks were styled in the lower-longer-wider and more aerodynamic ideals that began to set the Italian designers apart from others. Its sleek lines are surely aerodynamic-looking, albeit the central grille-mounted “torpedo” detracts some from this. Nonetheless, a neat example of how to properly set an aerodynamically valid car with very basic and simple touches, without the extreme features of the contemporary Bertone-bodied, Scaglione-penned concepts and without some exaggerations seen on other similar Ghias done on Italian chassis-and-drivetrain combos, like some Fiat 1900s and Lancia Aurelias, interesting for the reworking of Exner’s and Nash ideas, but somewhat out of the true Italian Style movement. I also like to think that the “torpedo” deeply set in the center of its air intake was borrowed by GM stylists as a starting point for the development of the Pontiac Club De Mer front treatment: In my opinion, all that was needed was only a bit of stretch, making the “torpedo” wide enough to occupy almost entirely the air intake. Maybe also my opinion is a bit stretched, but among many other cars of that period, the dimensions and the proportions of those two concepts are pleasantly similar (although the Pontiac is a far more extreme open sports car).

The latter one, the Blue Ray (Raggio Blu in Italian) is even more striking , especially in the first original version (there were two of them, in fact, the younger one seen in 1958). It was basically built to showcase the tuning ability of Enrico Nardi, then renowned not only for his steering wheels, but also for the various engineering experiments he was always ready to propose. The Blue Ray offered a classic Aurelia V-6 in the typical 2.451 liter format, “souped up” with many internal modifications, modified intake manifold and a set of Weber 40DCZs atop it. Horsepower hit the remarkable number of 190, not bad considering that the starting point was an engine offering, in all likelihood, no more than 118 ponies. This car wears an unmistakable body, with the peculiar “dual dome” windshield and roof combo, resembling both the Lincoln Futura and the GM Firebird II and III, and, in profile, the striking Hispano Suiza H6C Dubonnet Xenia of 1938 built by Saoutchik, surely a milestone car in the entire automotive world (it also predates some rear fenders design seen on Colonnade Pontiacs of the Seventies!), but the end result is much closer to a road legal car than any of those two well-known Detroit dream cars. The aerodynamics of the car must have been quite good, also thanks to the low front, with the typical (for an Italian concept of the day) headlights ensemble of one in center and one each on the extremes of the grille, because estimated top speed was reputedly close to 140 MPH. The sleek rear window, so similar to a number of other concepts of the day, can also be considered as the forerunner of many later concept and production cars with similar fitting. Interesting, for our discussion, the look of the rear pods housing the taillamps: They predate the look of those fitted on ’60 Cadillacs (albeit they are in a smaller format, they sure look like those of that quintessential luxury Yankee chariot). Interesting also to notice the fittings of two small fins, in an unusual position - one of the first time the fins didn’t run the entire length of the rear fenders, ending their run before. This shows some degree of future Dodge touches, though the dimensions and the proportions of the Italian car are impossible to compare directly with the ones seen on those Mopar creations; in effect, this is something that would be seen, on more grandiose proportions, on the GM Firebird III. More curious, and likely a casual fact, the two toning treatment looked very much like the one adopted in the very same months on ’56 Studebaker light trucks line…

However, I chose to write something about these two cars because they surely represent quite another interesting ability of the Italian Style real stars (and Michelotti, Vignale, Segre and Boano were surely among them): Bending external ideas to their own will, even if there was the difficulty to adapt them to something quite radical as a purity of lines or the need for the maximum aerodynamic efficiency, without forgetting to obtain an eminently practical car; with these two cars, surely there is no danger to think they look absurd or they are not suited for the road. To the contrary, they look like they belong to the road, not so taken for granted in an era of starships and jet planes with wheels.

It Is All A Matter Of Proportions: Men-Shakers And Ideas-Shakers

Sometimes we tend to forget that one of the best heritages left to us by the surging of the American automobile industry was the development of in-house design and engineering studies, often linked together. But the same thing happened in Europe - it was an obvious step further toward the modernization of the whole industry, a necessity of sort. But it is always surprising for everybody finding such similarly conceived working ideals in much smaller firms rather than the usual mass-producing giants of the industry. Leaving apart all those prosperous firms scattered across Europe, offering technical or stylistic help for everyone needing their inputs on a given project, I’d like to see how two of the most remarkable Italian legends of the automobile had often chosen to let external talents to be brought within their firm, leaving them free enough to develop watershed ideas, and then blending them with in-house efforts, so to become immortal pieces of art. They are Pinin Farina and Ferrari, and it couldn’t be any different, because, despite the existence of a whole Italian car scene with many offering striking similarities with them, they became icons of this way to use men, ideas, approaches and results.

Starting from this mere observation, and because here I am talking mainly about car styling, I want one more time to point out the fact that PF's ability always lay in the way he and his staff were often able to predate most of the decisions soon to be taken by practically everybody else in the automotive world. Sometimes this simply meant that some quite radical approaches were toned down and in their place appeared classic solutions, solutions already seen here or there, and maybe already a few years old. But thanks to this wise work of adaption and dilution, some excesses became the quintessential elements to transform a mere car into a statuesque masterpiece, a car soon to become a watershed design, soon to be imitated. But what is most interesting about this theme is linked to the proportions because I think the most interesting feature offered by this continuous reworking of others’ ideas resulted mostly in such distinct proportions that they are the reason why we can consider watershed designs cars that for a reason or another, had details seen already elsewhere.

That’s a sort of Ipse Dixit concept, I know, but how many times were we offered with the notion of the importance of the Cisitalia 202? This was a car which can be considered as the heir of a long tradition of “aero” fastbacks seen both in Europe and America, yet almost every critic agrees that it is a true masterwork, and without it the design world would surely be something else entirely. Yet it is easy to see that this car is a good reinterpretation of already seen ideas, but done with such a wise use of novel proportions that it instantly became a form of art. Art, not mere design, to the point that it also represents, with no scandalistic comments from jealous coachbuilders, one of the ways of working for which PF became famous: the possibility for the Turinese firm to be more a receptacle for geniuses and so becoming sort of ideas-shaker than anything else, all this with a wisdom rare to find elsewhere. After all, Enzo Ferrari himself was often considered a men-shaker for similar reasons, with his ability to concentrate a critical mass of talents led by his charisma toward a simple and unequivocal target, quite unlike many other automotive entrepreneurs, too much often pulled or pushed here and there for the sake of marketing, engineering or design, but rarely motivated for a very long time by rather simple approaches only. We can remember William Lyons, or Ettore Bugatti, or Vincenzo Lancia, but in my opinion much of their own genius came undiluted to production concepts.

In the case of Battista and Enzo, they not only left others to bring out revolutionary concepts for them, they also pursued one simple cause since day one: the cause of beauty and perfection in the case of the former, the case of the purest, most effective sportiness in the case of the latter. And when the time for a revolution came to them (and their firms), they made it in such an explosive way they became also inventors of something new, rather than simple manipulators of alien concepts. In fact, as the time went by, there were occasions when they had to accept stimulating things coming from outside, not even brought to them by all those talents working under their aegis. Yet their great wisdom afforded them to comply to these new feats with such a superb solution they happened to be seen as the anticipators of something new, rather than being mere followers for the sake of change or marketing issues. And this alone is plenty enough to make them icons. All this became interesting because there could be an entire chapter dedicated to the influence and following both Pinin and Enzo had and gave. But we are here for debating about car design, and because I think the most interesting feature offered by this continuous reworking of others’ ideas resulted mostly in so distinct proportions So, I want to give a pair of examples as homage of this, and if I have reserved a special role for the quintessential Pinin Farina watershed design of the Fifties, the Florida/Flaminia concept - with two dedicated chapters - it is because it deserved them. Too important the styling of the car to be merely inserted as a sort of example alongside others, too evocative its lines for the following cars, too evident the influential role that ideas brought from elsewhere had on its development. Well, for each of the following cars a pundit could say the same, but some influences were somewhat more subtle, both those sustained by the designers while forging these cars shapes and both those sent around the world after they appeared. But subtle is not exactly the first thing one could link with them, from a purely esthetics point of view. I am not talking about the Cisitalia 202 SC, which by the way, was co-authored with Giovanni Savonuzzi, just to remind how many important names were working with PF. I am talking about Lancia Asturas and Ferrari Superamericas. Let’s start with an imposing Lancia Astura (but which Astura wasn’t imposing by default?). An Astura penned by Mario Revelli (again, always him, always there, always here: What Michelotti was to the Fifties and Sixties, what Scaglione was to the Fifties, what Giugiaro was to the Sixties and Seventies, well, Revelli was to the Thirties and Forties).

The Lancia Astura was the Lancia flagship for the Thirties, with a conservative but also forward thinking chassis and drivetrain, decidedly a Lancia worthy of its name. In general, the standard models were usually traditional sedans, and the most renowned models were the ones bodied by outside coachbuilders. Pinin Farina built some of the most renowned ones, with one bearing again the Mario Revelli de Beaumont signature on it (it is important to remember that, as an idea-shaker, Pinin Farina could host also the most iconic Italian designer of the Thirties, in the same way Fiat had chosen his ideas for the development of the standard production 6C 1500: in other words, this is another example of the exceptional versatility of this artist). In this case, the importance of this car lies especially on the wise use of some of the latest ideas from America, but with some Italian peculiarities which would come in handy for American designers also. The imposing car (built for Galeazzo Ciano, son-in-law of the Duce) followed the recently seen mantras of faired-in-fenders headlights, a prow-like grille, complete with “catwalks”, and delicious fastback rear. One can assume that Cord 812, or Pierce Arrows, Graham “Spirit Of Motion” and regular Fords and Lincoln Zephyrs could be its inspirational leaders, and in effect it could also be true.

So, why did I decide to put this car here, instead of being used as an intriguing example of American influence? Well, I think that the contemporary designers were motivated to follow suits coming from America, and as such practically everything on wheels in Europe duly obliged to this (with some notable exceptions), but Revelli once again put some novelty of his own on this design. The general slim window frames and the resulting A and B pillars, and the general window treatment, were done in such a way that it is not difficult to foresee a certain aura of Lincoln Continental coupé on it (and explaining why the thin pillars of that Dearborn masterpiece were always considered so advanced), but with even less angular and much more rounded contours. The adoption of a curved windshield; the cowl treatment, typical of the era, and the decorative inserts on the hood sides, close to Detroit fashion but appearing also as a wise choice for a perceivable reduction of the side heaviness); the superb-looking tail, almost teutonic in appearance, but so long and moulded in such a way it almost predates some well known Forties fastback. I see some hints of 1941 Mopars on it, and of course the lengthy proportions lend also to the famous Sedanettes of GM (albeit the general shape is different: as said, it is all a matter of proportions).

In sum, I think that this Astura can easily be seen as the forerunner of those magnificent GM fastbacks seen around 1948, not in the details, but more in the general flavor their shapes had. Although it can sound a bit far-fetched, because the fastbacks seen in Detroit must usually be considered as more advanced than those coming from Europe (and so explaining why also the immortal Cisitalia 202 SC was blessed with a bit of American taste), I think that this Astura has such advanced proportions and such unusual details blended together that it is quite apart from contemporary flowing tail cars, and easily on par with Torpedo-styled GM of years to come (this Astura was built in 1938-’39, on a Series IV frame), and so it can be considered as the forerunner, at least from an ideal point of view, of all those American cars looking so sleek in fastback form, especially the aforementioned first postwar models coming from GM. Sure, the European fastback world back then had plenty enough of similar design too, but while they often appeared conservative for one reason or another, especially in the mass-produced form, certain others could well be put on par with this Lancia. Its exclusivity lies elsewhere, in effect; and while few European cars of the day could dare to touch it on this respect, fewer still from this side of the Alps could compare with it.

And in fact it is still difficult to find such remarkable proportions, such intriguing detailing (the curved windshield, clearly a lovely interpretation of those radical screens appearing on many German aerodynamic concepts of the day, looks in profile like a wraparound type, very much like a ’55-’56 Mopar) and such dignified demeanor like in this car. So, what set it apart is all a matter of proportions, as the title of this chapter explains. The car looks longer-lower-wider, the Italian way to apply this Harley Earl fideistic mantra, and some details enhance this, rather than making it appear heavier looking (there is also the application of chromed moldings very close to some Flamboyant French solutions, but here they didn’t appear the most striking feature of the car: they are instead used to make the car even longer looking, a wise choice considering also the elegant bleu paint adopted). The most interesting detail here, curved windshield and integrated headlamps aside, must be the adoption of the recessed, swing-type door handles, a Revelli invention and soon to become the quintessential handle for a generation of Italian cars of the Forties.

But Asturas would deserve an entire chapter regarding how many of them were influenced by American fads, wouldn’t they? Well, it is easy to think this, once a pair of them are taken in consideration. But what set them apart from the typical Detroit model which could work as inspiration was, once again, their general proportions. They worked so well that even in “blatant” copies of so typically American touches like fencer-masked grilles (and some of them with Silver Streaks too!), or fully covered front and rear wheels (a la Chrysler LeBaron Newport) it is impossible not to see some sort of cleverness in bending those touches to the will of the Italian bodies’ creators. These references are important because many later Asturas looked like overgrown General Motors product, but with such voluptuous curves, such astounding volumes, such magnificent proportions that they instantly looked like the out-of-the-ordinary machines they deserved to be. It could be sometimes difficult for an American not to see the distinctive shapes of something coming from Pontiac, Flint or Lansing among those Lancia’ shapes, but the derogatory soubriquets of Grown Pontiac, Blown Chevy or Inflated Olds end when its is clear how long, low and wide those Italian-made cars appear, especially if seen from the rear. Even a ”traditional” ’36 Astura by Stabilimenti Farina, in its sober shapes, could look like a billionaire chariot in the right color combinations, and all this without revolutionary lines or special effects, almost bordering on the grotesque or the caricature. The idea of a grown-up Pontiac or Oldsmobile maybe was a bit reductive, maybe derogatory, but while in hindsight isn’t far from truth it must be added that the ornate, the decorative add-ons, some tacked effects and many gratuitous touches – often already appearing on American cars – were used with such a talent, such a parsimony, that they added flavor, instead of looking too pompous, heavy or unnecessary; in other words, simple, taken for granted or commonplace touches worked every bit as well as the added decorations or baroque detailing often seen on those flamboyant foreign cars, and when there were decorative moldings, two toning and the likes on certain Italian cars, they often looked like the right thing in the right place. Exaggerations would be seen decades later, for now balance is the byword, and balance would do wonders for the Italian style in the early postwar years. But its beginning can be seen as early as 1930.

Even in the case of a two toned Astura, but even more in a dark monotone combo, it is clear that the Italian Style was already beginning to evolve toward its soon-to-be-shown ideals of better proportions and clean look above all else, gaining an allure of its own after having accepted the aerodynamic and shape lessons taught by Americans and other European school of designs. As the time went by, this became even clearer, and likely no Forties Italian fuoriserie was so perfect an example as the spring ’47 Astura brought to us again from Stabilimenti Farina, the firm created by Battista Pinin Farina's big brother, Giovanni. This was another firm with prestigious designers to help their efforts, the ubiquitous Revelli De Beaumont and Pietro Frua above all. However, the car I want to shortly describe looks more like the Italian cousin of the aforementioned LeBaron Thunderbolt, but this translates also in certain incredible touches that reminds also some exceedingly exceptional French creations. To put it bluntly, it combines the best of the two worlds, just what Italian Style was also beginning to be accustomed to do (and reckoned to be able to do).

This Astura bodied by Stabilimenti Farina (relatives to PF) would be noted for its astounding dimensions (all Asturas were immense cars for the Italian roads and typical cars of the day, a coupé-sedan by Touring was likely the longest road-legal two door ever seen in Italy with a full 20 feet of length - not that the described PF Series IV was compact, with its similar length, but the Touring car was sleeker yet) and a nice touch, soon to become George Mason’s favourite trademark for the upocoming Nashes: the covered wheels, both front and rear. This touch, so used by some remarkable French Grand Routieres, was indeed rare in Italian-made creations (the Aprilia Aerodinamica by Pinin had such devices, but in this case they were adopted for the noble scope of a land speed record), and it pretty much looks like the feature seen on the ’41 Chrysler prototype, and makes this imposing car, built on an old long wheelbase – 133 inches of span - ’35 Astura frame, recovered from a decrepit ministerial sedan, even longer-looking than it is in reality. In fact, the proportions obtained are not only low and long, but also very wide for that time, because of the need to have, despite the covered wheels, proper space just to make the front ones turn sufficiently for the twisty Italian roads of that era. In effect, this car has a good road behavior, thanks to very good brakes and suspensions (important features for a 5,000-pound car with an estimated length of 19 feet, and also quite similar to the kind of roadholding the PF Astura can bring to its driver) and despite the covered front wheels at least it can still be driven to appreciate the smooth (if somewhat short on horses) V-8, its torque and its effortless aplomb (at least 80 MPH are attainable). So, a car perfectly suitable for the American roads, so much so that in the end it looks even more suited to be an American car than the ideal ancestors. In fact, it is undeniable that the general fenders look (in full pontooned fashion), the lengthy rear volume, the spectacular front end, the low windshield (no sci-fi here: two simple flat panes of glass, centrally divided), all conjures up to give the idea of an American car. But what set apart was especially the voluptuous modeling of the fenders, both front and rear ones, done following the Buick ideals (and the Saoutchik-bodied ’39 Talbot Lago which must be considered as the ancestor of all those Forties cars with similarly shaped fenders, Jag XK120 included), but made even more plastic, with smooth contours and the peculiarity of flush-fendered bumpers, a striking touch especially evident from the rear. This alone is quite a novelty, but what in effect makes us marvel is the globally effective way used by its creators to make an imposing car appear also incredibly sleek, so much so that it was once compared to a hovercraft on four wheels. It is a sort of compliment, and something difficult to spot on other contemporary cars with similar details.

All this made it original enough to both earn it an award at Monte Carlo Concours d’Elegance, and most important, first place at the ’47 Concorso D’Eleganza in Villa d’Este and to appear intriguing enough to surely make some soul in Kenosha to give it a double look (after the close study of the Thunderbolt concepts and all those flamboyant French chariots, obviously). After all, I don’t think there are so many cars wearing covered wheels both fore and aft and still remaining so simple, so pure and so dignified in profile, with no needless chrome, moldings of various genre, heavy decorative touches and so on. Just like the original Airflytes, this car relies more on the sculpted effect of the sheet metal, rather than on anything else, to obtain an idea of plastic shape and movement (and in this, it is even more effective than the Airflytes: as said, Stabilimenti Farina’s artisans chose an approach closer to the one followed by Flint boys while molding their ’42 Roadmasters, than a full height fenders shape like, say, a ’47 Kaiser. This was a good idea, for the dynamic effect is mesmerizing, despite the monumental amount of metal, and the dark paint). It is also extremely intriguing to see that the rear fenders themselves had a vestigial fins treatment, something the LeBaron Thunderbolt didn’t have, and something looking very effective to lend further sleekness to an already absurdly long car (at least for the Italian tastes and roads of the time). So, this explains why this car can be considered good enough to be hosted both in a chapter about the American influence on the Italian cars and vice-versa: I opted for the latter option because it shows that the other spectrum of the Farina galaxy could obtain masterpieces like Battista “Pinin” Farina and still be able to show something new to the world; sadly this kind of new soon became old, for the covered wheels was an idea that, George Mason apart, never touched the heart of many people (there were imitations in Italy, however, for example an Aprilia by Pinin Farina but this kind of experience was quickly superseded; however, as we’ve seen, not before some truly remarkable prototypes, for example the Alfa Romeo B.A.T.s, used them to a certain extent). Last but not least, Buicks built between 1950 and 1953 model years would offer a profile treatment of the fender contours pretty much alike the one seen on this Astura. Certainly Ned Nickles and pals could use the ’42-’48 cars as a direct source for a starting point when shaping their new models proposals, yet it is interesting to see that the way the rear fenders are attached to the upper rear edge of the continuous line of the front one is very much alike the treatment given by Stabilimenti Farina on its Astura. Interesting touch, isn’t it?

Sadly, this car would also be one of the last examples of how good Stabilimenti Farina was in using so daring touches, against all odds. In fact, simply because the firm execs (in other words, Giovanni’s sons) didn’t want to trust their latest consulting newcomers, Giovanni Michelotti and Alfredo Vignale among them, and their equally innovative ideas, and so the firm soon lost talents providing it with such enthusiastic designs, and in 1953 it floundered. A pity, even more acute considering how Pinin Farina, Michelotti and Vignale would contribute to the birth of one of the most (if not the most) admired schools of design in the world. A school where sobriety and elegance were always linked with dynamism and innovation.

Sobriety, however, is not the first word one can link with the following series of cars. Glamorous is a much more apt adjective, so much so in fact that some of them could easily make the just described Asturas as champions of understatement. Enter the Ferrari with the “cylinders as big as flasks,” to use the own words of their creator. Enter the Ferrari Superamericas and Superfasts, cars that could easily found a place with a chapter of their own explaining why they were so heavily influenced by the American Style, yet founding a good place here too, thanks to the “unsuspecting” influence they exerted on the role of the super sports cars of the nearby future, and on some American trends for the years to follow their debut.

But maybe, their most important legacy could be the fact that thanks to them the name Ferrari became even more famous in the United States. If for no other reason than thanks to their names, it soon appeared clear what was their first and most important market, and in effect, although it became also some of Intercontinental Ferrari, because nobody in Italy or Europe, or wherever there could be people with cash and connections, was deterred from buying it despite their incredible exuberance. If this is not enough an influence for the American automotive world, then, let’s also take a look at some of the concepts they quickly promoted. It must be remembered that the luxury image linked to Ferrari products started when Enzo gave an almost exclusive chance to pen his cars to Pinin Farina, and this began with the 212s, but not until the arrival of such incredible cars like the 375s, certain 250s and the various Superamericas and Superfast, the aura of an exclusive “toy for riches” began to have equal dignity with the initial idea of a Ferrari destined “only to race and consequent wins.”

The Ferrari 375s, 410s Superamerica, Superfast, the 400 Superamericas and the later 500 Superfast are quite iconic cars, not only because of their “dedicated” market so proudly written in their same name, but also because they are the apex of an already experimented phenomenon, soon to become ubiquitous through those industries producing similar cars: Their most powerful cars could also be the most luxurious ones, not only a perfect Spartan gun to win races, but a magic chariot to display the owner's power and richness. This was a concept already seen in prewar cars, of course, but rarely a car born to be the fastest, most powerful one, also resulted to be the most luxurious - the costliest maybe, but not equipped with items cared for by comfort-seekers also. Now, these Most Ferraris Of Them All started a postwar reawakening of this concept, but because they were among the first Ferraris not expressely destined for racing, and still they were incredibly fast, with no compromising prowess, it became clear that the time of the Duesemberg SJs had come back, although now there was the novelty of a luxury car proposed by who otherwise was used to build competition-type models only, or as a main part of its production.

This was a sort of revelation, for before these Ferraris, if someone wanted a given fastest car, usually had to cope with compromises for comfort and sheer luxury. From the 375/410/400/500s on, it would be possible to have the best of both, maybe not on the level of a 250 GTO or a Rolls Royce, but more than enough for the kind of clientele that had otherwise to buy two totally unrelated cars, a car perfect for the jet-set used to own also other kind of vehicles. ”Vehicles” is quite correct as a term: Not only luxury chariots masked as extravagant cars, but also airplanes and, most compelling of them all, luxury boats and yachts, the first hints at what became a typical tycoons and variously rich men phenomenon. Trying not only to have grand manors and hugely vast bank accounts, but also being surrounded by moving objects attesting their owners’ status. This was in reality nothing new, but what was somewhat more subdued in the prewar era, likely because it was a thing seen in few countries, mainly in Europe and North America, in the booming postwar years would become commonplace also in other continents. In other words, these were also the first Intercontinental Ferraris, perfect for racers seeking for a similarly fast vehicle, or playboys in need of qualified wheels for their own personal living. These two concepts are similar, yet very different: In the case of the Ferrari 410s, later 400s and 500s and also Maserati 5000 GTs, first and foremost came the performance, then there was also the explicit consideration that they were the richest offering from their respective factories, superior to even their illustrious but “smaller” brethren, and in effect, before similar cars took foot in the Fifties and Sixties, it wasn’t always taken for granted that the most luxurious ones were also the fastest. There were examples of them, but they were a rarified minority among the ranks of ultraluxury machines.

Just a few words about some of them. The Duesenbergs were first of all the grandest cars of their era, but for truly super Duesies you had to look at the slightly smaller 125-inch span SSJs, otherwise the differences between the normal Js and the supercharged SJs were mainly in the mechanicals, while bodywork and interior appointments were usually quite akin. The same can be said about Bugattis, with the implication that the Royales were likely the fastest Mulhouse thoroughbreds mainly because of their “exaggerated” displacement, intended first of all to move with dignity those immense “tanks,” and many a super luxury European Grand Routiere pre-war car could be also comparable to those Ferraris, like some Bugatti Type 57s, some Alfa Romeo 8C 2900s and practically most of the Mercedes 500/540 Ks, the latter ones likely the closest in concept to the Ferraris. But in the postwar years, these kind of Mercedeses were somewhat toned down (until the arrival of the 600 even a superb 300 SL paid some penalty to the super luxurious and super sporty 500/540 Ks, at least in cubic inches), Bugattis and Grand Routieres Delahayes, Salmsons, Hotchkisses and Delages went the way of the dodo, Alfas did nothing so outrageous until the late Sixties 33 Stradale (and still this was not in the same 8C 2900 category) and so newcomers like Ferraris, Maseratis, Facel-Vegas or prewar rare sights like Jaguars, Aston Martins duly occupied that rarified niche. The novelty of the Ferrari concept was that while the prewar firms also were deeply set in production of luxury vehicles as far as appointments are concerned, Ferraris were up until the Superamerica's debut first of all destined to racing, with relatively few concessions to exceedingly high margins of comfort. Sure, cars like the 375s or the Grand Toring 250 GTs implied that they were destined to some sort of intercontinental fast trips, thus they were obliged to offer more comfort than, say, a Topolino, but with the Superamericas the whole concept could and would be taken further up the ladder. Now, Enzo had understood the importance of this item also for the insistence of some part of his customers, for a while he followed their discreet suggestions, and from this time on, automotive history would change forever.

Therefore, in my opinion, with the arrival of the 375s and even more, of the 410s, on the market, the concept of an ultimate sports car with only Spartan appointments and rough interiors began to be more subdued, and the idea of a very fast car that could also offer the very best a plutocrat desired also began to spread. What’s more, and what is important in this context, even Americans took notice of this new mentality. Otherwise, how could one justify following cars like the Dual-Ghia, with coachbuilt exclusivity and performances to match, or the 1956-on Chrysler 300s Letter Series, becoming more and more luxurious and also generous with comfort options as well as performance-oriented items (the first 1955 edition was a harsh ride, albeit done over nice-touch hide, with limited paint choice too, and no tachometer or air conditioning available; the ’56 300B already had the air available, and the Hi Way Hi Fi was also there should the would-be buyers have preferred Rossini or Bach instead of a raucous Hemi), or, coming back to Europe, the 300 SL becoming a nice and beautifully optioned convertible instead of remaining, in the Gullwing original formula, more a race car than anything else? After all, even others elsewhere had perceived that the fastest in their range had also to be the most luxuriously-appointed, or at least the finest: The ’55-’57 T-Bird is a darn perfect example, and also the performance granted by the early Eldorados made them perfectly comparable to the grandest Ferraris of the time. However, Enzo took the concept a step further, with the help of people like Pinin Farina, his staff and Sergio Scaglietti (the latter also created a 410 featuring curious rear fins, quite close to the tacked-on affairs seen on Buick’s Wildcat and production ’54 Skylark, and distinctly similar to the one seen on that “absurdity” on wheels that’s often considered the Gaylord).

It is remarkable to notice that if Enzo reinvented this kind of car, well, sort of, also he wasn’t deterred from proposing again Spartan road rockets: the F40 is the first example coming to my mind – the 250 GTO and the 250 LM were first of all conceived for the racing course, unlike the F40, but also the Dream Machine Of The Eighties could hold its own on tracks. But cars like the contemporary Bugatti owes as much from their illustrious ancestors as well from these first Ferraris for VVVIPs. And I also dare to say that without such mergers between all-out performance and all-out exclusivity, also the whole concept of trying to offer something comparable but somewhat diluted (so to be available to more than a rarified elite) could also came to nil, if there would be such a spectacular example to follow; in other words, what Americans started to call personal-luxury cars maybe would never be offered also with raucous powerplants as options, leaving them to all-out sportscars. Maybe it is a bit far-fetched, but I personally think, and I like to repeat, it is a mere opinion of mine, that without such illustrious examples like the SuperFerraris, also the efforts of the Letter Series would be without heirs. Instead, as we know, the formula of luxury-cum-performance-cum-comfort became the quintessential theme to pursue, but offered with the roominess of a 300 and the design exclusivity of a Ferrari 410/400/500. In sum, thanks to these cars, already existing ones muted their shapes (the original Thunderbird becoming the four-seater T-Bird), or continued their existence on the market despite their producers' woes (the Studebaker Hawks and even the Avanti), or were proposed by firms almost immune to this kind of concept, yet desperately in need of a reinterpretation of those famous Fifties halo cars that once made them such a good service, and now had to look distinct enough so to not look like overgrown ‘Vettes: so, this alone can explain cars like the ‘62 GP, the ‘63 Riviera, the ’66 Toros, the ’67 Eldos and, consequently, the ’69 Conti MKIII. Sure, they were no extreme two seaters like the Ferraris, but they had plenty enough of glam and oomph, just like the Prancing Horse original. They were also conceived as affordable alternatives to the spreading European market sector of the Gran Turismos, which became an exploding (albeit the numbers remained elitist) spectrum and explored also by others (think one for all of them: Aston Martin). Without forgetting the Fifties granddaddy of them all, albeit not quite so super exuberant as far as performances were concerned: the Bentley Continental.

This same concept also endured a long success as a marketing item to be exploited elsewhere, because even in the pony and muscle car era, the most potent editions of Mustangs, GTOs and the likes could usually be optioned also with the most luxurious items readily available through the dealers: testify to this the fact that the Goat itself became more and more sort of Grand Touring car rather than pure race-bred cum family-car combo. Sure, a Super Duty Pontiac, a Max Wedge Belvedere or a 409 Biscayne don’t apply here, but the success of the ponies and of the hottest mid sizers was mainly linked to the incredibly vast opportunities left to owners in making their cars even more personal; this could be accomplished through money, of course, so it was common to see that a well-engined Chevelle ended also to be a very nicely equipped package (and the ’65 Z16 was the Chevrolet personification of a five-seater Ferrari Superfast, in case the ‘Vette isn’t used for immediate comparison purpose: the Z16 was the hottest horse in the Bow Tie corral, destined to Bonanza actors and nothing less, equipped with Bach-power stereos and other costly comfort-related items, and the whole car gave an intoxicating mix of comfort and performance levels not usually found on ‘Vettes or 396/425 hp Biscaynes); not until the fall of ’67 debut of the Road Runner, the concept of a first and foremost fast vehicle again available with few Spartan frills came back, just like the old days of the European race car of yore (in this case, the Road Runner was even more extreme, because despite their Spartan status, no Ferrari 166s, Maserati A6GCs or Porsche 356s, no Jag XKs or Mercedes 300 SLs was ever be considered also all that cheap to buy). Speaking of Maseratis, it is also interesting to note that the 3500 GT was since its debut modeled like a proper Grand Touring car, not like a pure racing car: The influence of very fast cars created expressly for very fast touring trips was felt also in Modena, surely a thing dictated in part also by the changed evolution of certain Maranello products.

The 410s are therefore important because they epitomized all things a Ferrari had become famous for: exclusivity, fantastic performances, exotic looks of the type you rarely see on the road, charisma thanks to the racing activities that were producing year after year, success after success, an incredible pedigree, something only Bugatti owners could have experimented in the past. The fact that the 410s were also the most American-looking among all Ferraris is also sort of undeniable statement, a logical consequence of the desire to be The Car To Have for the happy few, those happy few happy enough with fins, chrome and wraparounds, of course. But in those years, as we’ve already seen a dozen times so far, American flavor was the dominant fashion, a byword of up-to-date statements, and so it is no surprise if even most sedate 410s and some memorable 400s and 500s later on had incredible fins, or were based on lines used on pure concept cars, like a certain PF-designed Alfa Romeo of the time, the famous one with fins and Plexiglas-covered front wheel cutouts. However, they were usually bravely diluted in Italian fashion—after we have taken a look at Savonuzzi’s creations, it is quite simple to think that the razor-edged, sharp fins seen on some Italian creations were more trademark of Italy rather than the United States, after all up until 1955 those kind of fins were more likely to be seen on certain Motorama and Italian coachbuilt creations, rather than on mass-produced Detroit cars.

A well known example can be offered by the similarly styled 250 GT and 410 penned by Boano, (the former being the Geneve, already described in the first chapter about the American influence), with their incredibly sharp and convex-curved fins closely resembling those later offered by ’60 and ’61 Ramblers, ’60 Fords or, from some point of view, ’59 Buicks and Chevys. While this seems somewhat contrasting with the huge influence America had on Italian cars, it is also true that American fins remained for a time subdued (before exploding later in the Fifties), while on certain Italian cars they were already pretty much sharp. To make a comparison, American fins looked like they belonged to a propeller-driven airplane, while the one sported by some coachbuilt extraordinary ltalian cars looked like they were taken directly off a jet fighter. Of course, the American ability to translate them into something for the masses is undeniable, and the success endured by some American cars (namely Cadillac) also spurred Italian efforts, and the debut of razor-sharp ’55 Eldos made things going faster still. But devices like the fins seen on the Savonuzzi cars and the 410s are also example of how far the concept could still go. Now it would need Exner’s Forward Look to show this at its devious best. As for the jutting prow of many a 250 and 410 of the era, this also influenced somewhat some American firms, although pundits can always tell that the original ’53 Corvette face was the real ancestor of those low, rakish, aggressive Ferrari stems. Maybe so, but it was likely impossible to reach the same results without taking the same trails. Considering the results, compliments to everybody involved in this kind of operations!

In this case, I’d like to think that the impressively aggressive inverted trapezoidal mouth seen on Chrysler 300 Cs, Ds and Es was conceptually inspired by these Italian cars also, and not only by the various Ghia-bodied concepts made since 1951, because it surely helped the meanest Mopar machines to achieve an even greater sense of road omnipotence, giving instantly the idea of an impetuous car, ready to devour everything that couldn’t get away from them. This, plus the necessary air flowing to keep the engine from becoming too much hot, and also giving the added gift of necessary cool air for the voracious pairs of Carters lurking under that enormous hood. The same could also be said about the Ferrari's needs, though the aerodynamics research made by PF and others surely invited Italian stylists to avoid such an imposing front end on their creations. (Of course, on special request, sometimes they obliged to do things really heavy-looking: take a look at the Gianni Agnelli’s 400 Superamerica, with its front end which looks like a makeshift imitation of a ’59 Letter Series car.) The direct 410s heir, the 400, is also interesting, because it translated in a production car a then striking detail that would became much more common in the later years: horizontal taillamps deeply set within bumper edges. While this was again possible to imagine as an American influence (since it was seen as early as 1953/54 on the Motorama’ Pontiac Strato Streak albeit its immediate heir, the ’55 Strato Star, sported something resembling Fords ideas, and was also used as another daring touch on that incredible BMW 507 designed by Raymond Loewy), the fact that those GM cars sporting a conceptually similar item had reverted to a quadrangular design or a vertical one (in 1959 and ’60 respectively, only on ’61 models the twin set of taillights were set in a horizontal manner, like the clean and super swift-looking Prancing Horse finest model) says a lot about another nice example of using other ideas and then improving them on part of PF staff. In effect, the whole rear end look of the 400 closely predicts what would later be seen on the immortal Jag XKE (aka E-Type), and in both cases we are looking at the quiet, and much needed, evolution from the vertical lights and fins era of the Fifties toward the sleeker Sixties fashion. However, the 400 front end now doesn’t have the protruding mouth, this being more integrated in the general front end profile: this is not a problem, but an improvement; an improvement dictated also by the spectacular Lancia Zagatos seen as early as 1957 (in both Appia and Flaminia ranges): starting with that idea, Pinin Farina would later offer other essays of similarly pointed front ends, showing the whole world his (and his men's) ability to further improve the examples offered up until then by cars like the Citroen DSs, the Porsches and the Loewy Studebakers of ’53-’54. From then on, those desiring similarly conceived touches had to revert to the Italian Maestro’s ideas, rather than trying again shapes used by those famous French, German and Yankee cars.

Fastbacks And Wraparounds

After taking a look at the former chapter stars, it is almost by default that the fastback way to Italian style must be looked upon. Vice-versa of sort is also worthy notion: the Italian way to the fastback style.

This is an interesting item: Here we have a design feature developed and exploited by American stylists, and then brought to Europe and lasting far longer, to the point of being reinstated by fashion once again, after many years of decay on American shores. That’s the fastback concept, another one of those “difficult-to-say-who-invented” design, yet surely at the foremost of the same American car culture for at least 15 years. 15 years full of development, abruptly halted by another revolutionary concept, the trunkback or notchback type sedan and coupé; combined with the hardtop style that, dare I say ?, made the fastback superfluous in America. Or at least, Joe Public said this once he had entered in a dealer’s showroom, regardless of the marque. However, in Europe the style lasted, prospered, never really retrenched and, what’s more, with the lovable help of some Italian cars, also offered new possibilities to the entire automotive world. While it is easy to understand the remarkable achievements of such renowned cars like the Cisitalia 202 or the Lancia Aurelia B20 GT, and a whole host of Ferraris, Maseratis , some pretty last French Grand Routieres, the indomitable Bentley Continental or the upsurging Porsches, there are at least two more obscure Italian cars worthy enough to be counted among the masterpieces that helped to create the original Italian Style, and, even more important to notice, they also influenced American designers thanks to their styling originality and features, originality and features looking convincingly good and up-to-date also on far different cars than the nimble Italian (or European) fastbacks. Their features, if taken singularly, weren’t maybe all that new, but their use and the way those cars’ looks appeared, surely made a good point for prompting Detroit men to use them on their creations. Or, at least, every time I give them a look, I can’t think of anything else. Others will be free to think in a different manner, but surely some style-wise similarities are there.