American Modified to Xcess - 1970 AMC AMX

The only NASCAR-spec, AMC-propelled, Trans-Am suspended, blister-fendered, cage-stiffened, street-driven '70 AMX you're likely to find

09/23/2018

The year is 1984.

You're given a muscle car. It just drops into your hands, and it's yours, free and clear. What do you do with it? Put it in mothballs? Restore it to as-new condition? Fill it with Sunoco Purple and boil the tires 'til they explode?

Ah, but this wasn't any old gift horse. This was passed down by your uncle--an uncle you shared an enthusiasm with, an uncle who nursed and stoked the flames of high performance within you. In the days when these were just neat 15-year-old cars, rather than $50,000 investments, the temptation to modify them was strong. Perhaps doubly so with AMCs, as parts were harder to find in those pre-internet days, so going the aftermarket route was a simpler alternative to finding NOS pieces. Easier just to fudge repairs and make a quarter-mile killer out of it, right?

For shame: Your generous uncle would be so disappointed in you. For this isn't just a hypothetical situation--the gift AMX, and the uncle, were very real. "At the time, many people were modifying the old muscle cars for drag racing," recalls Hal Lynch, now of Ahwatukee, Arizona, the recipient of a 1970 AMX. Now, while AMC had a factory drag-racing unit, it wasn't nearly as successful as the company's road-racing and Trans-Am efforts. Hal's uncle, Don Lynch, the second owner of this particular 1970 AMX, had made his desires known prior to his passing. "His dream was to build a high-performance road car that could compete with European supercars of the day." That day coming in the early-to-mid 1980s, cars like the Lamborghini Countach and the Porsche 928 would fit the bill.

With Don's passing in 1984, the car was willed to Hal, who traveled from his then-home in New Jersey to Hartford, Connecticut, to rescue the AMX. The Bittersweet Orange two-seater, with 92,000 miles on the clock, was built within the last month of production, during the week of May 30, 1970. But, for what Hal had planned--the fulfillment of his late uncle's dream of having a street car competitive with Europe's best--things like original mileage and serial numbers mattered little.

"My uncle wanted it built as a high-speed road car, but I was mystified back then as to how to do it when I got the car. Then I saw some of the vintage Trans-Am cars from the early 1970s and thought to myself, 'Nobody can debate the high-speed roadworthiness of a car built from original Trans-Am and NASCAR road-racing parts!'" So Hal set out to find what he could, and fabricate what he couldn't.

Oh, Hal claims that what you see here wasn't meant to happen, of course. "I was just going to do some minor performance upgrades and things got out of control," he protests, not entirely convincingly. But the thoroughness with which things were executed tells us that Hal had a plan.

It started with an engine--the centerpiece that Hal wanted to build his AMX around. He could have sourced a 401 and gone to town rebuilding it, but that lacked a certain... pedigree. And so the search for some Mark Donohue-era Trans-Am equipment was on.

That search took literally years of phone calls, bad leads, blind alleyways and wrong turns to stumble into an AMC gold mine. "My biggest score was finding a Mark Donohue team car; it was owned by Bob Fryer and was being campaigned at the time by the University of Pittsburgh. The team had bought out many of the parts from the Bobby Allison team, including a complete engine." Among the surprises: a set of four 58mm Weber carbs on an AMC intake. "A team of engineering students then adapted the Webers to the NASCAR engine and planned to run it in the old Donohue team car. Unfortunately, multiple carburetors were outlawed for the class the Javelin raced in, so this fully developed race engine was mothballed."

As he thought it a shame to let such a highly developed piece of business sit in a back room in Pittsburgh, Hal generously offered to take it off the university's hands; along with the engine, innumerable driveline pieces also came with the deal.

You'll notice that, in our photos, the quad Weber setup is gone, replaced by a conventional Holley 750-CFM "double-pumper." "The Webers were a handful to keep adjusted, and in 1999, I removed them; I had the original NASCAR manifold, so I returned the engine to its original Bobby Allison configuration."

Today, it's topped with an Air Inlet Systems air cleaner that draws cool, dense air via fat dryer-ducting and openings on either side of the radiator support. "When the Trans-Am Javelins were built and tested, they discovered that the ram air intake on the hood was actually a low pressure point. High-pressure air intake points on the Javelin and AMX are in the grille or at the base of the windshield. I chose the grille." And let us save you a trip to the White Pages to track Hal down: He sold the Weber carbs and intake to a vintage Can-Am racer (and bought a new pickup truck in cash with the proceeds).

For that period feel, Hal even went with dry-sump lubrication. "Dry-sump oiling was made legal for Trans-Am racing in 1971 because everyone was blowing up engines due to loss of oil pressure during hard cornering. The system uses a shallow oil pan with a large reservoir placed elsewhere in the car; an external pump provides pressurized oil to the engine and is not subject to loss of pressure during hard cornering forces. The sump holds 15 quarts in the trunk-mounted tank." Because this is not an engine you want to blow up in a hard corner somewhere.

Dropping the engine in was the easy part. Building the rest of the car to support 600-plus horses on the street was another matter entirely. Particularly for something that had road racing spliced into its genes, suspension was critical: "Replacing the front spindles with Stock Car Products Grand National spindles and custom building a full-floating Ford 9-inch rear, which allowed for adaptation of Wilwood road racing brakes all around, was one thing. The changes altered the suspension geometry, which had to be brought back to spec."

A roll cage--liberated from a dead Fox-body Ford road racer and adapted to the AMX's interior dimensions without hacking up the door panels or instrument panel--stiffened things up considerably and allowed the suspension to do what it needed to without the Kenoshan's unit-body flexing. Hal credits Don Schmitz of Kenosha, Wisconsin, for the installation of the Richmond five-speed, rear pump and cooler, and some of the key suspension components.

There was also the question of rolling stock. "I had seen these Panasports advertised in Autoweek, but wanted to first look at them before deciding. I happened to be on a business trip to L.A. and decided to go visit Panasport to look at them. The one-piece wheels were blanks, and they only had four 15 x 10s and two 15 x 8s left in stock, as they were switching to three-piece wheel technology. I bought them all and had them drilled for the NASCAR standard 5-on-5 bolt pattern that was on my SCP spindles and Ford 9-inch rear." Years later, Hal contacted Pana-sport and sought out a spare 15 x 10, just in case. Nothin' doin'. "They could only make three-piece wheels, and they told me I had four of only 21 ever made in the 15 x 10 size."

And then there was the other issue with the wheels: They were a little too wide. "Once I had the suspension finished, the Panasport wheels stuck out a good six inches beyond the factory body lines. I took the car to a custom coachbuilder who specialized in pre-war Packards and Duesenbergs, and they quoted me a mid-five-figure price to build custom steel flares! A friend of a friend introduced me to Jim Mitchell, who built custom Harleys at his shop, Mitchell's Customs in Chesterfield, New Jersey. I towed the car over to him with the tires all sticking out, showed him and his friends in the shop a picture of a Trans-Am Javelin and told them that's what I want."

It took time, with Jim working on and off between Harley jobs, but two years later--after three six-month sessions with the car--Jim had the fenders done using the same metal-fabricating techniques used on the Donohue Javelins: 16-gauge steel, continuous-seam gas welding, and an awful lot of hammering.

Other, subtler bodywork was performed as well. The bumpers were acid-dipped, removing all of the factory chrome and nickel, and saving a total of 15 pounds at the extreme ends of the car. They were painted the same DuPont Slate Grey Imron as the rest of the car--similar to the Charcoal Grey that AMC used in the '80s. "It's a standard Imron color that you can have mixed today," Hal tells us. It's hard to believe that the paint is coming up on a quarter-century old; there's no sign of touch-up, fading or scratching anywhere.

And there are other quietly custom touches as well. The billet-aluminum windshield clips and back-window straps with counter-sunk hex fasteners. The door trim, all shiny brightwork replaced by the same billet aluminum and countersunk hex fasteners. (Both pick up on the depth of the hoops in those massive Goodyear cheater slicks.) And if you're looking for the AMX logo on the driver's side C-pillar, forget it: It's gone, replaced with a fuel-filler neck to feed the fuel cell that dominates the trunk. The electrical connections between interior and engine compartment use "mil-spec" plugs, sandwiched behind the new dual master-cylinder reservoirs, which provide a quick disconnect for the engine harness, in the event of engine removal. The transmission is a Richmond five-speed, with a 1:1 fifth, and sports its own external cooler.

Everything is track-legal, and Hal could go out and pound pavement at the next open-track event if he so desired. He credits Mike Higgins, owner of Vehicle Performance Center in Phoenix, Arizona, for all of the necessary road-racing track preparation.

Getting all of these components to play nice together required a lot of effort in the form of adaptation and fabrication, and all the trial fitments and experimentation that entails. Curiously, though, Hal claims that one of the simplest aspects of this venture was getting Bobby Allison to authenticate the drivetrain components.

"I was driving around town in 1997, and noticed Bobby Allison was going to be signing die-cast model cars at a hobby shop nearby." Bobby Allison just showing up in your town doesn't happen every day, unless you live around Salisbury, North Carolina. "I hustled the car up on my trailer, and asked him if he would authenticate and sign the car and engine for me." Today, Bobby's signature rests on both the hood striker plate, flanked on either side by Earl's component coolers, and on the four-barrel intake manifold that runs on the car.

"It all came together within a few hours," says Hal of the opportunity to connect Allison with his former engine. Some time later, Allison was good enough to forward an authentication letter which reads, in part, "After inspection... it appears that the markings on the engine and accompanying manifold are consistent with the markings placed on 1975-'76 NASCAR engines built by my race team and Reed Cams." This, and other factors, "leads me to believe that the bottom end of this engine was formerly used in AMC NASCAR Matadors and Hornets run by my race team in the 1975-'76 racing era."

Today, such an undertaking would be simultaneously simpler and more difficult. The ease of finding bits has increased greatly with the advent of the internet, and those years of phone calls could well have boiled down to a couple of months of online noodling. That's the simple part.

Everything else would have gotten more difficult. For one, "Owning, restoring and customizing AMCs is a labor of love, since there are no aftermarket part suppliers for many AMC parts--you need to build your network of other AMC enthusiasts and watch online auctions diligently. I'm collecting spare parts now. A NOS grill cost me $1,700, but was also the only one I have seen for sale in years."

And that's the other thing. NOS pieces, all these years later, are going for insane money. And race-tested pieces? Genuine parts that had seen track time? If they're not living on period-correct vintage race cars, then their prices would be impossible for an average Joe to meet.

The result of Hal's efforts was unleashed in 1991, and has changed nary a bit in the two decades since, with only suspension tweaks. The basics remain as they have, but even two decades on, and many laps passed under those Hoosier cheater slicks, there's still much more to learn, fiddle with and have fun with.

OWNER'S VIEW

I've always been intrigued by the concept of building a street-legal road-race car. When you're hanging around road-racing guys, they'll say race cars are just a bunch of parts flying in close formation and in the same direction.

If I had to restore this car all over again, I still wouldn't change a thing. It was a lot of work and even more money, but the joy of seeing it in the garage every day makes it all worth it. To this day, I cannot think of another car I would rather own.

-- Hal Lynch

PROS

+ Family lineage can never be replaced

+ Neither can that Bobby Allison NASCAR engine

+ You'll never see another like it

CONS

- Good luck getting into it

- Holy cats, is this thing loud

- Limited driven miles

1970 AMC AMX SPECIFICATIONS

ENGINE

Block type -- AMC "second-generation" cast-iron OHV V-8

Cylinder heads -- AMC cast-iron OHV, 71.9cc combustion chambers

Displacement -- 414 cubic inches

Bore x Stroke -- 4.235 x 3.725 inches

Compression ratio -- 12.96:1

Pistons -- BRC forged

Connecting rods -- Carillo forged steel

Horsepower @ RPM -- 600 @ 5,500

Torque @ RPM -- 590-lbs.ft. @ 5,500

Camshaft type -- Reed solid-lifter flat-tappet, model R306-10ULX-6A2

Duration -- 274 degrees intake, 277 degrees exhaust (at 0.050)

Lift -- 0.618 inches intake, 0.560 inches exhaust

Valvetrain -- Ferrea stainless 2.02-inch intake valves and 1.65-inch exhaust valves, Traco 1.6:1 ratio roller rocker arms

Fuel system -- Holley 750-CFM "double-pumper" four-barrel carburetor, Holley electric 110-GPH/14-PSI fuel pump

Lubrication system -- Home-constructed dry-sump system with remote 15-quart reservoir, Melling high-volume oil pump

Ignition system -- MSD billet HEI distributor

Exhaust system -- Hedman headers, twin side-exiting exhaust pipes

Original Engine -- AMC 360-cubic inch V-8

TRANSMISSION

Type -- Richmond five-speed manual, 11-inch McLeod clutch, Hurst floor shifter

Ratios:

1st -- 3.28:1

2nd -- 2.13:1

3rd -- 1.57:1

4th -- 1.24:1

5th -- 1.00:1

Reverse -- 4.79:1

DIFFERENTIAL

Type -- Ford 9-inch full-floating rear, Torsen-Gleason gear-driven limited-slip

Ratio -- 3.25:1

STEERING

Type -- Saginaw recirculating ball, power-assist

Ratio -- Variable (12.0:1 to 16.0:1)

BRAKES

Front -- Wilwood 12-inch rotor with six-piston calipers

Rear -- Wilwood 12-inch rotor with four-piston calipers

SUSPENSION

Front -- QA1 coil-over conversion with 600-pound springs, Stock Car Products Grand National front spindles, gusseted lower control arms, 1.25-inch anti-roll bar

Rear -- Georgia Spring semi-elliptic leaf springs, KYB gas shocks (rear anti-roll bar and Panhard bar not installed at time of shoot)

WHEELS & TIRES

Wheels -- Panasport one-piece aluminum

Front -- 15 x 10 inches

Rear -- 15 x 10 inches

Tires -- Hoosier R3S04

Front -- 275/50-15

Rear -- 275/50-15

PERFORMANCE

Acceleration -- Not tested

So…you’re thinking about buying a Mustang, huh? Can we talk? Having the privilege (and curse) of owning nine late model Mustangs that span four generations, I understand. Have a seat, and let’s go for a drive…

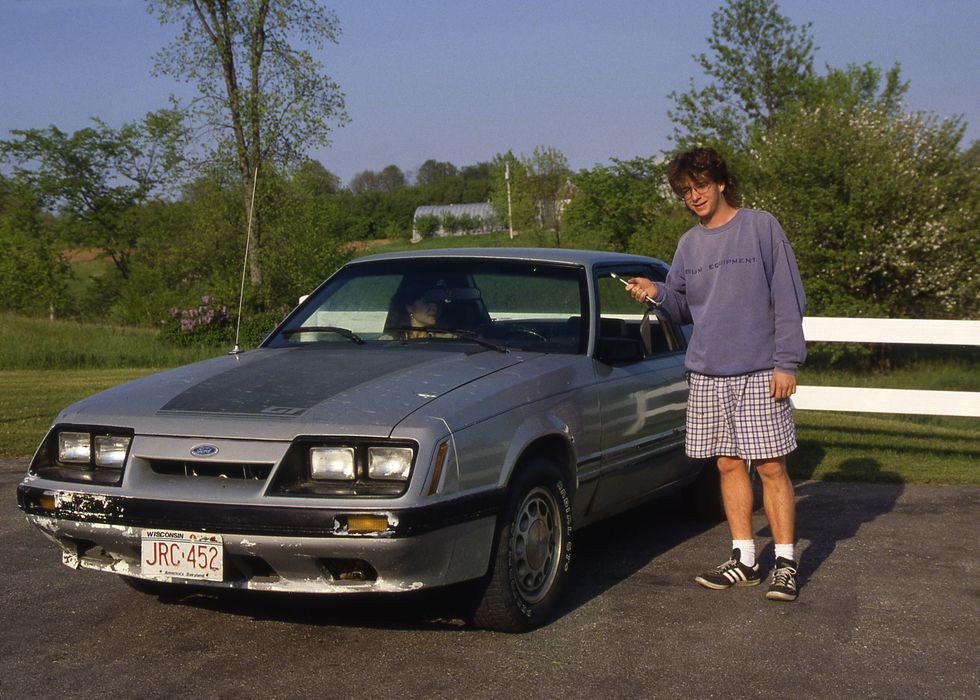

I didn’t start out loving Mustangs. In fact, a few days from concluding high school classes my senior year, I was determined to buy an affordable car for college (and tinkering). Only stipulations: it had to be rear wheel drive and V-8 powered. Bonus points for three pedals. I found something a mile from my house that was within my budget (read: clapped out). It was a five-speed 1985 Mustang GT.

My initial relationship with Mustangs was less of a love affair and more a marriage of convenience. Ever since that first Fox-body GT, Mustangs have repeatedly ticked the boxes of what I like: modest size, V-8 soundtrack, stick shift, and copious customization potential. Familiarity bred comfort. It’s only as I approach thirty years of Mustang ownership that I realize, “Huh, I really LIKE these things.”

It's from this perspective that I’ll share frank advice for novice late model Mustang shoppers.

By “late model,” I’m referring to 1979-current Mustangs. They span five generations and forty-five years: 1979-1993 (3rd generation), 1994-2004 (4th generation), 2005-2014 (5th generation), 2015-2023 (6th generation), and 2024-present (7th generation). Rather than discuss each generation individually, I’ll approach this from an attributes angle: What you’ll like about a Mustang…and what you’re probably going to hate about a Mustang.

(Note: we’re only going to discuss V-8 Mustangs because nobody cares about the others. Change my mind.)

Yeah, it’s subjective. Each Mustang generation has a “vibe.” You want to resist the urge to look back at your parked Mustang, not be embarrassed by it.

Photo: Hemmings Archives

The Fox Mustang styling is kinda polarizing. You love it or hate it. They’re boxy and edgy. As my teenage son’s friend quipped upon viewing his first Fox-body Mustang: “I’m not sure if this car is cool or ugly.” It’s both! If you’re into the Radwood scene, grew up careening down country roads at triple-digit speeds either in (or behind) a 1979-1993 Mustang, it’s going to bring back memories. That’s the point.

Photo: Hemmings Archives

The SN-95-era Mustangs are aesthetically “husky.” While it structurally continued with the same chassis as the Fox, the SN-95 was complete rejection of the previous generation’s hard-edged design. There’s not a straight line on (or in) a 1994-'98 model Mustang. A facelift in 1999 brought some sharp creases back to the exterior sheet metal, but the interior was unchanged. Because the 4th generation continued with the 3rd generation’s underpinnings, SN95s are basically flabby (in both proportions and weight) Fox Mustangs. Wonky proportions notwithstanding, the styling resonates with some owners, and their popularity is starting to tick up.

Photo: Bryan McTaggart

The S197-chassis Mustangs put 1960’s styling on a modern chassis. If you dig retro styling in a modern, roomier, and safer package, a 5th generation Mustang is for you. The 2005-'09 models “got the band back together” with body panels, lighting, and a greenhouse that isn’t just a nod to the 1965 Mustang—it’s a reunion tour. Sure, the guys put on a few pounds over the years, but their teeth are straighter and whiter, and they all stopped drinking. While it’s not the same old hellraiser, there’s a lot to like here. The 2010 Mustang got a facelift that was further updated again in 2013.

Photo: Ford Motor Company

The S550-era Mustangs are the first of the breed to be officially sold worldwide and were designed to resonate with the diverse tastes of global buyers. It’s sleek and athletic. It was so good that its silhouette is visible in worldwide models from BMW and Kia. A 2018 facelift shrunk the schnoz a bit to improve both aerodynamics and aesthetics. It’s a very “safe” design that will likely age well. Where the S197 is an A-10 Warthog, the S550 is an F-16.

Photo: Ford Motor Company

If you want a brand-new pony car straight off of the dealership lot, the S650 is your choice for Mustang. While the S650 is basically a continuation of the S550 chassis (see also: Fox to SN95 chassis), Ford’s stylists took the defeated Camaro as the pony car battle’s war bride, and the seventh-generation Mustang was spawned. Good thing or bad thing? You decide.

If the interior isn’t a noisy, punishing sweatbox…is it still a Mustang? Discuss.

1980 Ford Mustang Ghia interior. Note the flat-faced Fairmont-inspired dashboard and fragile center console.

Photo: Bryan McTaggart

The Fox-body Mustang's ergonomics are notoriously bad. If you’re tall or short, a Fox Mustang is not a fun place to be. Lanky drivers can’t slide the seat back far enough, and short drivers can’t reach the shifter. The steering wheel generally faces the door handle and can’t tilt if it’s an air bag-equipped 1990 and newer model. All the seats are soft and unsupportive by current standards. 1979-1986 models have a boxy dashboard and a wire-thin steering wheel. 1987-1993 models got an updated (and iconic) interior with a surprisingly long dashboard storage tray so your spare change and Blockbuster Video membership card slides around in corners more than the live rear axle. If you don’t know what either of those are, this is only the tip of the iceberg of surprises awaiting uninformed Fox Mustang shoppers.

1987-up Mustangs featured a face-lifted interior. Those cupholders are an aftermarket addition, taking the place of the ashtray.

Photo: Hemmings Archives

No, there ain’t any cupholders for your iced coffee, Karen. But if you’re of average proportions, outward visibility is refreshingly good and the back seats are surprisingly comfortable. There’s even an ashtray back there. The interiors on Fox Mustangs are cosmetically and structurally plastic—most of which is either cracked and broken…or will be soon. A Fox Mustang creaks, rattles, and twists like a pirate ship full of empty spray cans in a windstorm. Speaking of wind: there’s lots of that noise too. And if your Fox Mustang has some type of hole in the roof—be it a sunroof, T-tops, or (thoughts and prayers) a convertible, not all water will stay on the outside. If your Fox Mustang hasn’t had its heater core changed yet, then know that coolant can (and will) leak from there, too.

The SN-95 interior and its 1960s Mustang-inspired "dual cowl" treatment was first previewed on the 1992 Mach III concept car.

Photo: Hemmings Archive

SN-95 Mustangs inherited the weird ergonomics of the Fox generation and added droopy plastic that melts around you like a shop class vacuum forming project. The optional leather seats cracked just looking at them, so don’t be surprised if the seating surfaces look like Clint Eastwood’s face when you trapse across his lawn. (Aftermarket seats go a long way to increasing comfort and aesthetics in one fell swoop.) The 4th generation’s arched greenhouse makes taller drivers even more miserable than they are in a Fox Mustang, with rear headroom suffering the most. The interior is quieter than the Fox, with less wind noise and more sound deadening, which means you can hear more of the interior panels creaking. But hey, at least there are cupholders.

The S197 retained the dual-cowl theme but didn't leave the front passengers feeling claustrophobic. Certain models had adjustable gauge backlighting, allowing drivers to change colors as they pleased.

Photo: Hemmings Archives

The S197 Mustangs silenced many gripes with previous generations. Pre-production focus groups got us a vastly updated interior with a steering wheel that actually faces the driver, a reachable shifter, seats that don’t fall apart, and a roof that accommodates tall people. The standard seats are “meh,” so the optional Recaro seats are a plus. The back seats are sunk down far enough to yield good headroom so your passengers can ponder why they’re sitting atop a live rear axle rather than an independent rear suspension… but I digress. The throwback styling continues with the dual-cockpit dash pad and gauge cluster. The modern engineering and manufacturing techniques yielded massive strides in eliminating interior panel creaks and rattles and you can hold spousal discussion without shouting (at least over the wind and road noise). After you tire of arguing with your spouse, you can do the same with the SYNC system. Don’t worry: SYNC won’t understand you either. At least the cupholders are well-designed.

The S550 Mustang's interior was an evolution of the S197's overall design - clean, functional, and driver-focused.

Photo: Ford Motor Company

S550 Mustangs have a more immersive cockpit over the previous generation, where drivers feel more “in” the car versus “on” it. While it accommodates the driver and front passenger as well as the S197 Mustang, even average-height adults’ heads are squished against the sloping back glass if passengers are banished to the back seats of an S550 Mustang. The center stack has an infotainment system that is less irritating than previous offerings. A digital gauge cluster was optional on later models, which is either cool or gimmicky depending upon your attraction to tech. Again, the optional Recaros are brilliant. Get them if you can. Thick glass, copious sound deadening, and a creak-free instrument panel make the inside of an S550 very quiet pleasant. Aside from contemporary sports-car-style outward visibility, there’s not much average buyers would complain about. Weird.

The S650 enters the modern era with screens. Gauges can be changed, including a late-1980s Fox Mustang-themed design and a 1968 Mustang-inspired layout.

Photo: Ford Motor Company

S650 Mustangs feature a more “driver focused” cockpit with big screens that replace much of the mechanical switch gear. Utility and functionality is debatable. Fortunately, when you start actually driving the thing, it’s very much business as usual from the previous generation S550 Mustang. The greenhouse is a structural carryover, so all that’s good (and bad) with the S550 continues with the S650…including the optional Recaro seats. The park brake handle perseveres, but it’s now connected by wire to electric rear park brake calipers. The result is the park brake handle action is springy and lifeless—unless you use it in “drift brake” mode. Grab those cell phones and step away from the curbs, folks.

Aside from looking at or sitting in a Mustang, the allure of Ford’s pony car is about driving it, right? Strap in... and try not to die.

Courtesy of MotorWeek

These Mustangs drive like 1980’s econoboxes with too much torque, because that's exactly what they are. If you’re expecting blissful performance from a Fox Mustang, prepare to be disappointed. Just remember the famous quote, “Never meet your heroes.” Scores of Mustangs ended their lives (and sadly, the lives of their occupants) wrapped around roadside objects because the drivers didn’t respect the limits of themselves, the cars, or the drivers around them. 1979-1993 Mustangs aren’t bad, it's just that they’ve been hyped up so much that drivers have forgotten how miserable cars were back in the 1980’s. Over-boosted steering, squishy subpar brakes, stiff clutches, schizophrenic handling, harsh ride - this was all typical. And Mustangs were not the worst offenders (I’m looking at you, GM F-body!) A chassis designed for the 55-mile-per-hour speed limit is glaringly out of its element on 70+ miles per hour highway speeds. But getting to the double nickel is a hoot! Squeeze the gas on the five-oh and woah, you’ve buried that speedo needle. Speaking of “woah,” don’t expect the brakes to save you. Most Fox Mustangs only had 11-inch discs on the front and puny drums in the rear. (Cue the Mustang geeks arguing in the comments about the outliers with rear discs.) If things go bad, only 1990-1993 Mustangs have a driver’s side air bag…and it’s unlikely that it still works.

If you’re expecting a Fox Mustang to knock your socks off, that depends upon how rough the pavement is. Some buy a 4th generation Mustang expecting legendary performance and are sorely disappointed. Stock Fox Mustangs barely crack 200 horsepower. With about 3,300 pounds to lug around and plenty of low-end torque to do the lugging, they roast the puny 225mm-wide tires readily. But once the needle gets past 4,000 RPM, it’s a snooze-fest. Doubly so if the 5.0 is mated to an automatic slush box. The popularity of centrifugal supercharging and it’s top-end kick makes sense after driving a bone-stock Mustang five-liter: boost picks up where the factory power curve noses over.

But driving isn’t all about speed, right? Add some Flowmaster mufflers and you’ll sound cool while hustling up the onramp. You’re going to hear it anyway. The windows are rolled down because the air conditioning probably doesn’t work.

Courtesy of MotorWeek

1990s Mustangs drive like mature Fox-body Mustangs, so if you can stomach the styling, SN-95 Mustangs are more enjoyable than a Fox. With more weight comes less noise, vibration, and harshness. The air conditioning might even still work. While the first two years carried over the trusty five-oh pushrod engine, 1996-2004 models featured Ford’s 4.6-liter, overhead cam, modular V-8 engine. Even if the early “mod” motors were disappointments from a horsepower and torque perspective, they certainly are smoother and remain extremely reliable. At least all the bolts were finally metric.

Strides in safety are significant over the Fox Mustang, too. Driver and passenger-side air bags, anti-lock brakes, and optional (and primitive) traction control make SN-95s less lethal.

After leaving niche “high performance” variants to specialists like Saleen, Ford offered an in-house low-volume model: the Mustang Cobra. These Mustangs offer performance and a driving experience that’s significantly better than their GT counterparts in every way. Pricing aside, there’s no reason not to opt for a Cobra over a GT. Each subsequent Cobra offered more performance than the last, especially in the braking department.

The 2003-2004 Mustang Cobra aside, SN95 Mustangs are very slow. Especially if there’s only two pedals. All automatic transmissions in these cars were buzz killers. You can’t expect to win any stoplight duels with an SN95 Mustang, but that doesn’t mean they’re not fun to drive. Sometimes driving a slow car fast is more rewarding than driving a fast car slowly. (At least, that’s my excuse.)

Courtesy of Adam Kriete

The S197 Mustangs weren’t much faster than the outgoing model because the added horsepower and torque was offset with more weight. It wasn’t until the 2011 model where Mustang got the engine it arguably deserved: the five-liter “Coyote” V-8. With over 400 horsepower on tap, the Coyote really transformed the Mustang’s reputation from plucky puppy dog to an outright Doberman Pinscher. Mated with a six-speed manual gearbox, Coyote-powered Mustangs hurt feelings—and tires. Power discrepancies aside, all S197 Mustangs offer a driving experience that’s leaps and bounds ahead of anything before. Credit goes to a modern chassis where engineers weren’t forced to make as many compromises. Even the live rear axle (retained for reasons that remain debatable) was adequately tamed. Ford finally did a thing!

The 2005-2014 Mustang’s steering feels decent, you can skip leg day and still operate the clutch, the shifter knob easily falls in hand, and the V-8 soundtrack remains. The stiff chassis really pays dividends on rough roads: approaching potholes or bridge transitions is not a sphincter-stressing experience. Safety is enhanced with multiple air bags, modern brakes, and extremely effective traction control and anti-lock brakes. If safety is a priority (which it always should be) then I strongly recommend an S197 Mustang. There’s a lot to like. The biggest change (in my mind) was the five-speed automatic transmission doesn’t completely ruin the driving experience with sluggish performance. But get the stick anyway.

Photo: Hemmings Archives

These Mustangs are a joy to drive. Tons of power, responsive chassis responses, fabulous brakes, engaging driving position, and sure-footed handling make the S550 Mustang a go-to recommendation for the casual Mustang owner. It offers the most rewarding driving experience for the average driver partly because it requires the fewest compromises. The S550 Mustang is a highway weapon. My snark switch is turned off because it’s a great car to drive. Steering feedback could be better and the brakes less boosted, but these are a matter of preference rather than failings. The quiet cabin allows the exhaust sound to dominate the driving experience. While the automatic transmission options don’t suck, the manual gearboxes are so good you’re missing out by opting for two pedals. If you’re sitting in the Recaro seats, you’re going to love it even more. Clearer communication from the chassis to your torso transforms the driving experience more than you’d expect.

Photo: Hemmings Archives

Mustangs carry on the theme from the previous generation by retaining much of the same running gear. Steering feel is improved with a shaft that eliminates a rubber isolator. If you close your eyes while driving (not recommended), you’d be hard-pressed to differentiate between the S650 and S550 chassis—and that’s a good thing.

While a Mustang might be great to look at and drive, is it a headache to own and maintain? Is it going to strand you? Yes. No. Maybe.

Photo: Hemmings

Fox Mustangs are old cars by now—and they have old car problems. Fluid leaks (exacerbated by the popularity of synthetic lubricants) are all but guaranteed. “If there ain’t oil under it, there ain’t oil in it.” Valve covers, rear main seals, and oil pan gaskets weep with age. Rubber seals, once supple and compliant, are now shrunken and brittle. 1980’s electronics are also beyond their service life, as many of the components, such as capacitors, are leaking and no longer have their, uh, capacitor-ness. Some of these magic boxes (such as the fuel injection computer) are available rebuilt from the aftermarket—but some (like the air bag diagnostic module) are currently unobtanium. That blinking air bag light is going to be a fact of life. Refrigerant for the air conditioning is no longer available, so reviving the A/C is not easy if you don’t like sweating. Don’t get me wrong: a Fox Mustang can still be a reliable daily driver, but if much of it is original, bring tools. If reaching your destination without turning a wrench as an accomplishment, then a Fox Mustang is for you. But if you (or your wife) is in labor, don’t drive the Fox. Much of the reliability of a Fox Mustang is a function of how it was treated or how much has been replaced or updated. Fortunately, Fox Mustangs are very simple and conventional. You don’t need fancy diagnostic devices or special tools to work on them. If you’re ambitions, crafty, and bored—a Fox Mustang is a great project. However, if you’re not a do-it-yourselfer, a Fox Mustang will keep your mechanic busy and your wallet empty. So unless you like spinning your own wrenches, find something newer.

Photo: Hemmings Archives

Mid-'90s Mustangs are less of an ownership gamble than the previous generation. Through the decade of production the SN-95 Mustang got updated components that brought contemporary reliability. 1996-up OBD-II diagnostics made tracking down basic issues a bit easier, and the modular V-8 engine family (also in 1996-up models) reduced fluid leaks. Air conditioning did away with the old freon refrigerant and is more serviceable. However, the large physical size of the modular V-8s makes servicing anything out of arm’s reach challenging. Be prepared to cuss... a lot. Years of ethanol-spiked fuels have taken their toll on these early fuel systems, so failed fuel pumps are common. With Fox and SN-95 Mustangs, mileage is less of a factor than outright age. Speaking of mileage: if a prospective SN-95 Mustang has a mechanical odometer (1994-1998), don’t trust what it says. The gears on these units often disintegrated years ago, and the odometers no longer track miles. Wonderful.

Photo: Hemmings Archives

These Mustangs are less “classic cars” and more “used cars” at the moment. With this generation, milage is a larger factor over outright age. If a 2005-2010 three-valve V-8 Mustang is making noise, chances are it’s the timing components. It’s a common issue, and replacement parts are plentiful. When test driving an S197 Mustang, typical used car buying logic applies: if your senses suggest something doesn’t look, feel, sound, or smell right, have it checked out or find a better Mustang. The S197 chassis is the roomiest of the modern generations, so working on a 2005-2014 Mustang is a breeze. Modern assembly techniques focused on speed and cost mean fasteners are few and easily accessible. The aftermarket is awash in parts for these cars, making the S197 Mustang is also a great “first Mustang project.” You’re going to spend less time fixing broken stuff and more time making the Mustang faster or louder (and maybe both)!

Photo: Hemmings Archives

Mustangs are more sophisticated and confined than the previous generation, but everything is in the same spot and is built similarly. The biggest departure chassis-wise is the independent rear suspension (IRS). It’s significantly more complex than the live rear axle—good thing the IRS is robust. The S550’s engine compartment is more confined than the S197’s, but if you have small hands or patience, it’s not too bad. Fluid connections are mostly a click-together affair, so that’s a plus. S550 Mustangs are young and plentiful, meaning finding one that’s clean and straight is not difficult. Effort in pre-purchase inspection will yield dividends in service and reliability for years to come.

2024-current “S650” Mustangs are new and under warranty. Enough said.

Photo: Hemmings

Spanning 45 years, "late model" Mustangs have something for everyone. If you’re a crafty do-it-yourselfer, want people to chat you up at stoplights, and don’t care if something breaks along the way…shopping for a 1979-1993 Mustang is for you. If you’ll take flabby styling in exchange for a slightly more refined driving experience, enhanced reliability, and a classic soundtrack…consider a 1994-2004 Mustang. Looking for a great project car with retro aesthetics but modern performance that won’t strand you or break the bank? A 2005-2014 Mustang is on your list. If you’re new to Mustang ownership, want to drive it daily and experience what makes the internal combustion V-8 engine the greatest mechanical contraption in human history…find a 2015-2023 Mustang. If you want a new Mustang because it’s, well, new: the 2024 Mustang is it.

Glad we had this chat. Welcome to the Mustang cult.

RPO Z06 Makes the New-For-’63 Chevrolet Corvette Sting Ray Race Ready and Extremely Valuable

Due to changing external forces, General Motors had a fickle relationship with factory-backed racing in the 1950s and 1960s, and the corporation was ostensibly keeping motorsports at arm’s length when the second-generation Corvette was nearing its debut. This didn’t stop the engineers behind Chevrolet’s sports car from designing and building the specialty parts the new Sting Ray would need to establish dominance in competition. The Regular Production Option code Z06 was selected for 199 coupes, and surviving examples of that limited production run are considered the most coveted and valuable road-legal 1963 Corvettes in existence.

Regardless of what the official GM policy on racing was at the time, the Corvette team had long been actively encouraging motorsports and the glory that brought to this model and Chevrolet as a whole. Privateers who wanted to compete in their 1962 roadsters could specify RPO 687 to gain heavy-duty suspension and braking components, as well as a quicker steering ratio and 37-gallon fuel tank; ticking the RPO 582 box brought a 360-horsepower 327-cu.in. V-8 topped with Rochester mechanical fuel injection. Versions of these special upgrades would have a place in the new-for-’63 Sting Ray as well, for a time similarly bundled under RPO Z06, a.k.a. “Special Performance Equipment.”

Selecting this, a racing hopeful had to lay out a not-insubstantial $1,818.45 ($18,110 in today’s money) atop the $4,038 (circa $40,210) MSRP of a 1963 Corvette coupe that was also optioned with the L84 fuel-injected 360-hp V-8 ($430.40, or $4,285), four-speed manual transmission ($188.30, or $1,875), and Positraction limited-slip differential ($43.05, or $429). Later in the year, Chevrolet lowered the Z06 package cost to $1,293.56 ($12,880) by making the initially included cast-aluminum knock-off wheels and 36.5-gallon fuel tank —RPO P48 and N03—into standalone options. Even in its most basic form, a Z06-equipped 1963 Sting Ray was an expensive car.

And it has always been one, especially from the mid-2000s when retail book values shot up exponentially. Classic.com has been tracking the values of many variants of Chevy’s sports car for the past five years, and non-Z06-equipped 1963 models now sell at auction for an average sum just under $160,000. The Z06 variant is a special case, and although the website currently considers the ’63 Corvette Z06 to be a declining market benchmark at $510,165, it has hardly reached bargain-basement status—the current average public-sale price as of press time is $531,154. Thirteen Z06s have sold at auction since August 2019, with the least expensive being a coupe that changed hands via Mecum in Houston for $235,000 in April 2023, and the priciest being a sub-5,400-mile original that commanded $1,242,500 (the pre-sale estimate was $750,000-$900,000) at Gooding & Company’s Amelia Island event in March 2022. These figures handily outstrip current retail book values that range between $219,000 and $447,500.