July was the hottest month ever recorded and Colorado’s mountains didn’t fully escape it

Trapped under the same heat dome that enveloped the southwest U.S., Colorado's Western Slope started roasting early in July but by mid-month parts of the central mountain region were also heat breaking records

Tony Marzo/Summit Fire & EMS

As the earth roasted last month, reaching a global average temperature that scientists have confirmed to be the highest on record for any month, the Colorado High Country got an uneven sampling of the heat.

While parts of the southwestern Colorado Rocky Mountains were locked under the same heat dome that broiled states like Arizona and New Mexico, the northern mountain region mostly escaped that unprecedented pattern of heat.

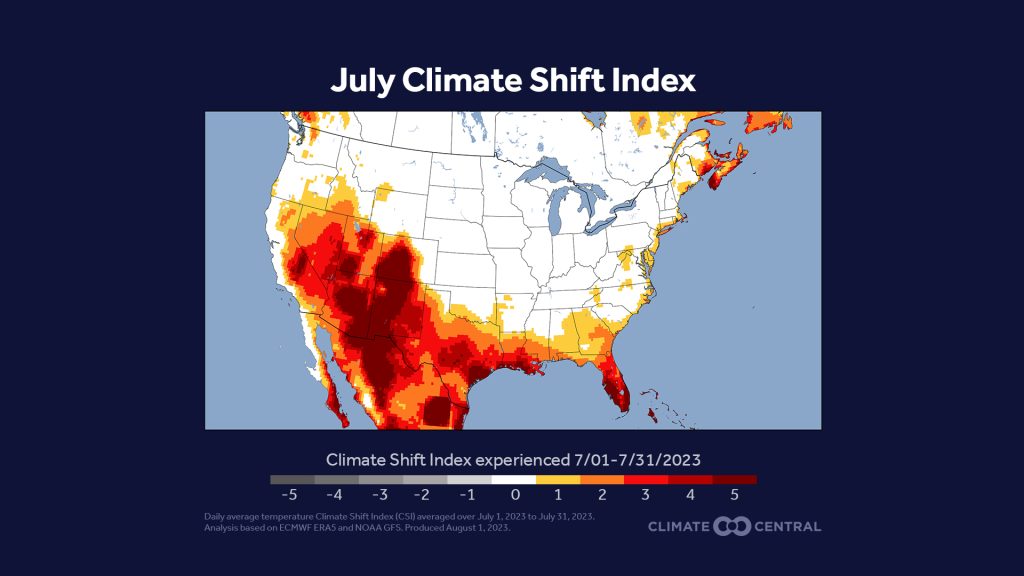

Still, most Coloradans, like people in many parts of the world last month, felt the influence of climate change helping to drive up temperatures. In the U.S., 244 million people — 73% of the population — experienced at least one July day with temperatures made at least three times more likely due to human-caused climate change, according to an estimate from independent scientists at the nonprofit Climate Central.

The record-breaking July was marked by heatwaves, “in multiple regions of the world,” a climate scientist told the United Nations this month. Based on data known as proxy records, which include cave deposits, calcifying organisms, coral and shells, the scientist said, it “has not been this warm for the past 120,000 years.”

The rising global frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, like the sustained and deadly heat wave in the southwest U.S., is consistent with well-established scientific understanding of the consequences of carbon pollution — mainly from burning coal, oil and natural gas.

According to the Copernicus Climate Change Service, at several points during July, global temperatures temporarily exceeded the 1.5 degree Celsius threshold above the 1850-1900 average — a warming limit set in the Paris Climate Agreement.

When global temperatures spike, some locales like the U.S. and Rocky Mountains, tend to be more sensitive to the overall climate change pattern than others areas, Climate Central director of attribution science Andrew Pershing said.

So, as the earth baked last month, Pershing said, the fingerprints of human-caused climate change were detectable in daily temperatures almost everywhere in the Colorado mountain communities at one point or another.

“We have these scary numbers — the hottest month ever probably in 100,000 years,” Pershing said. “It’s a little abstract. We don’t perceive that number, 1.5 degrees Celsius, at the global level. We don’t walk outside and feel that. You feel that through your local conditions.”

All sweaty on the Western Slope

Across much of Colorado’s Western Slope, July started out above average. Then it only got hotter, according to National Weather Service forecaster Brianna Bealo. The first triple-digit temperature day of the month in Grand Junction was July 11, Bealo said.

Then, all the way through July 31, the lowest daily high temperature recorded in Grand Junction was 98 degrees Fahrenheit, Bealo said. On July 17, Grand Junction Airport recorded a high of 107 degrees, tying the all-time high set in 2021 and smashing the previous record high for that day of 104 degrees set in 2010.

Stay up-to-date on all things Summit County. Get the top stories in your inbox every morning. Sign up here: SummitDaily.com/newsletter

“The month itself started a few degrees above normal,” Bealo said. “But it definitely took off with a hurry.”

For most of July, a high-pressure system brought warm temperatures to the Western Slope that also kept conditions dry, Bealo said.

That same heat dome brought cities across the United States to a boiling point. On July 25, Phoenix, Arizona, recorded a temperature of 119 degrees, topping the daily air temperature record by three degrees, according to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Phoenix recently endured at least 27 days with maximum temperature exceeding 110 degrees, and El Paso, Texas, suffered for 42 consecutive days at or above 100 degrees, NASA reported, adding that “extreme heat is the leading cause of weather-related death in the U.S.”

Right on the edge of that heat dome, the influence of climate change on Colorado’s Western Slope last month is irrefutable, Pershing said.

“In July, we really saw especially the southern third of the country, basically coast to coast, was unusually warm,” Pershing said. “And we were able to say there was a very strong climate fingerprint most days in that region.”

Climate Central’s daily attribution tool, the Climate Shift Index, applies the latest peer-reviewed methodology to map the influence of climate change on temperatures across the globe every day.

By comparing the existing climate to models of a world without human climate influence, the Climate Shift Index calculates how much more frequent extreme heat is on average now than it would have been in a world without greenhouse gas pollution, Pershing said.

On an overlay of the U.S. or world map, the tool outputs a level between 1 and 5 over geographic regions. Level 1 indicates very little human climate influence, while Level 3 is associated with a strong climate influence and means the hot conditions experienced in that region were made at least three times more likely due to climate change.

“Really what we’re trying to do is make this connection between the big climate change problem and what people are experiencing day to day through their weather,” Pershing said. “We’re not going to make a causal statement, but you can get close to that.”

Nearly every day in July, the daily temperatures in the Grand Junction area showed a strong climate influence, several times maxing out the Climate Shift Index atLlevel 5. Level 5 events — conditions made at least five times as likely due to greenhouse gas pollution — would be very difficult, but not impossible, to encounter in a world without climate change.

Other parts of the Southwest under the same heat dome showed even stronger indicators of climate influences. Santa Fe and Albuquerque, in New Mexico, and Mesa, Arizona, averaged a Level 4 or higher on the Climate Shift Index throughout July, according to Climate Central.

Pershing said remove climate change from the equation and it’s hard to imagine a summer like what most of the southwest experienced.

“Thats been kind of the remarkable thing about the event in the Southwest,” he said. “It’s just been day, after day, after day, after day — the persistence of that event is even more remarkable to me than the extremes.”

The red badge of Colorado

Even as Colorado’s Front Range and central mountain regions escaped the heat dome that hung over the southwestern part of the state for most of July, the fingerprints of climate change became visible as temperatures climbed later into the month.

On average, July temperatures were just below normal in Denver, right around average in Boulder and about a degree above normal in Dillon, according to National Weather Service forecaster Russell Danielson.

“Generally speaking the plains were about a degree below normal and the mountains were about normal to a degree above normal,” Danielson said.

The Front Range and central mountains tapped more into the cool weather witnessed in Denver, with most areas getting average to above-average precipitation, Danielson said. After starting off cool — if not downright chilly some places in the mountains — July got increasingly warm in the central mountains, and the signal of climate change began to emerge.

In Dillon on July 1, there was a high of 66 and a low of 29, making for a cold start to the month, Danielson said, but by July 25 temperatures had warmed up considerably, with a high of 84 degrees record that day.

This echoed weather patterns in Denver, where the high on July 5 was only 71 degrees, 11 degrees below normal, Danielson said. But, by the end of the month Denver International Airport hit 97 degrees on July 23, 98 degrees the next two days and remained above 90 through the rest of the month, he said.

For several days in late July, Denver hit levels 4 and 5 on the Climate Shift Index. And, although some Denverites escaped to the mountains, where elevation offers relatively cooler temperatures, the fingerprints of climate change were present there too.

Through the last week of July, Denver, the Front Range and the central mountains region reached level 4, or “extreme” on the Climate Shift Index at least once, meaning climate change made the balmy conditions at least 4 times more likely to occur.

“The main thing is that Colorado has been at this edge in July,” Pershing said. “Where you are in the state, which day, determines whether you’ve been tuning into the plains pattern or the southwest pattern.”

While Colorado’s central mountains were not locked into the same heat dome pattern that gripped the southwest in July, at the start of August, Hurricane Hilary helped shift the high pressure system east, trapping almost the entire state beneath it.

“When I look at the maps from our Climate Shift Index, Colorado is just really glowing bright red, Level 5,” Pershing said. “Those daily temperatures are five times more likely, or more, because of climate change. These are the conditions that you should expect to see more and more frequently as the years progress.”

Fahrenheit 2023

Until humans curb carbon emissions, global temperatures are only projected to increase. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, there is a 99% chance of 2023 ranking among the top five hottest years on record.

Regardless of how 2023 ultimately ranks, the World Meteorological Organization estimates that there’s a 98% chance of at least one year between 2023 and 2027 exceeding the current warmest year on record.

Coloradoans should expect more months like July in the years to come, Pershing said.

“The U.S. is a big country, but we’re only a small part of the planet,” Pershing said. “There were a lot of other places in July that were experiencing really unusual heat: southern Europe, Spain, Greece, the Middle East, the Persian Gulf region, Iran, China.”

That’s the true story of July, Pershing said. Not only was it hot in Colorado, but it was hot throughout the world — and it will only continue to get hotter if humans don’t take action to curb greenhouse gas emissions, he added.

“If it were just one of these places around the world, you might say natural variability,” he said. “The fact that this is happening all over the world is just a really clear signal we’re dealing with a climate that has been altered by humans.”

Extreme heat can be a major stressor on human populations, Pershing noted, calling the July temperatures a “buckle up” moment for society. Already, CNN has reported that at least 147 people in just five U.S. counties have died this summer from extreme heat, “a mere snapshot of the fatal toll.”

“Heat is just this pressure that gets pushed onto society,” Pershing said. “You see places that are stressed. Those are places that start to break. People who are unhoused, dealing with addiction, poor, working outside, those are the people you really see impacted by these events.”

Just because some mountain towns in the Colorado Rocky Mountains have the benefit of elevation to help keep people cool, climate change could still have significant impacts on local ecosystems and economies, Pershing said.

In many places in the U.S., winters are warming faster than summers, applying pressure to the winter sports industries that crave cold temperatures, Pershing said. Especially in the High Country, where plants and animals have evolved to survive through long, treacherous winters, that warming will also have a significant impact on the environment.

“That’s probably the thing that is the most at risk when you’re talking about the Rockies, this beautiful natural area,” Pershing said. “The environment that the animals and plants are encountering is very different from what they evolved to be able to handle.”

Limiting warming to 1.5 degrees or 2 degrees Celcius will require global emissions to peak by 2025 at the latest — and “deep, rapid and sustained emissions reductions” throughout 2030-2050, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

That will take a collective and concerted effort to achieve, Pershing said, but people across the political spectrum are coming to recognize the threat that climate change poses.

In Colorado, legislators last year passed a law pledging to reduce overall greenhouse gas emissions by 26% below 2005 levels by 2025, 50% by 2030, and 90% by 2050. There are currently 22 states with 100% clean energy goals, according to the Clean Energy States Alliance.

“I think the most important climate solution individuals can take part in is to talk about it,” Pershing said. “Talk about it with your friends, with your neighbors. This is a part of the world we can’t get away from. We have to be able to talk about it the same way we talk about other challenges and stresses in our life.”

Support Local Journalism

Support Local Journalism

As a Summit Daily News reader, you make our work possible.

Summit Daily is embarking on a multiyear project to digitize its archives going back to 1989 and make them available to the public in partnership with the Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection. The full project is expected to cost about $165,000. All donations made in 2023 will go directly toward this project.

Every contribution, no matter the size, will make a difference.