My sister was working for Paramount Pictures when I first visited Soho as a wide-eyed teenager. The place had been a home for the film industry since at least 1908, when colour film pioneer Charles Urban moved into offices on Wardour Street. In the 1970s, all the big film companies had offices here.

The Guardian’s product and service reviews are independent and are in no way influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative. We will earn a commission from the retailer if you buy something through an affiliate link. Learn more.

Dirty, smelly, noisy Soho was an unbelievably exciting mixture of pubs, restaurants, cafes and markets. And the people! Spotty, chain-smoking youths wheeling handcarts piled high with film cans narrowly avoided being hit by taxis as the most multinational and multicultural mix of people I’d ever seen surged around the streets.

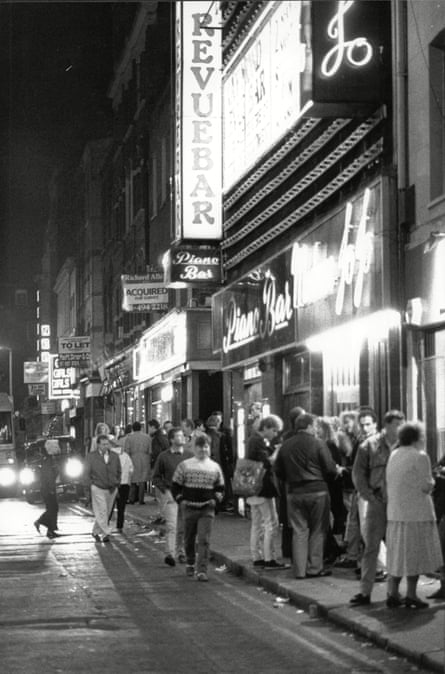

But let’s face it, for a teenage boy, Soho had one other key attraction: it was very, very naughty. Red lights were everywhere and every other entrance seemed to be a strip club, massage parlour, sex cinema or sex shop selling magazines and 8mm home movies. Displays inside and outside the shops, sometimes plastered on entire walls of buildings, were as graphic as the law – or rather, the notoriously corrupt “porn squad” of the time – would allow.

When I started as a reporter on the film industry trade paper Screen International, the area was still dominated by the sex trade. By the mid-1980s, things were beginning to change. Westminster council, under pressure from some high-end residents, began clamping down on the sex trade, refusing to renew licences for sex shops and closing the many illegal video shops that had sprung up to capitalise on the new VHS boom.

Within five years, the gay community had started taking over empty shops and bars, and from the flat where, as an independent film producer, I now lived and worked, I saw the transformation of Old Compton Street in the 1990s into a vibrant hub of cafes and shops fuelled by the “pink pound”.

Old, louche Soho carried on in the shape of pubs such as the Coach and Horses and the York Minster (now called the French House), clubs such as Gerry’s and the Colony Room and illegal drinking dens. New, louche Soho showed its bleary face in the wave of contemporary clubs such as the Groucho, Blacks, the Union and Soho House. An evening out for me usually lasted from 7.30pm to 7.30am and involved walking less than a hundred yards, as there were just so many places to drop into, with so many extraordinary people to meet.

Soho has always been a village and historically it’s been a village full of low-lifers and high-lifers, romantics and realists, drunks and dreamers, sex workers and bar workers – every walk of life is represented. But one thing binds us together – a ferocious loyalty to the place.

Even though the alleyway on which I live could accurately be described as “dodgy”, it still feels the safest place I’ve ever called home. People have always looked out for each other in Soho, and if a girlfriend was ever bothered by a random guy as she was unlocking the door to my house, you could bet that a local dealer, working girl or strip-club caller would be at her side like a shot, checking that she was OK.

When I moved into the flat, the restaurant owner below my old place organised trollies with the local market workers to shift my stuff down the road. When I was locked out once, one of the local pimps rounded up some of his clients to join me in yelling for someone to come down and let me in.

Of course, there’s always been a dark side and even my somewhat rose-tinted spectacles allow me to acknowledge that. But to date, despite the best efforts of the police and gentrifiers, no one has been able to prove that a Mr Big is moving behind the scenes of the sex business, in the way that the so-called Maltese mafia ran the vice trade in the 1950s and 60s. The women I know are hard-working, self-employed girls and their treatment was deplorable during the questionable police raids at the end of 2013 (which happened to coincide with a Westminster council meeting to vote on the demolition of some historic buildings and construction of a steel-and-glass eyesore that even the council’s planning department thinks is oversize and poorly designed).

That raid really marked the latest phase of gentrification in Soho, where it seems like every other building is being gutted or demolished to make way for expensive flats, most likely to be bought by overseas investors. Much of this gentrification is fuelled by developments such as Crossrail 1 and 2 (the latter of which threatens to destroy the Curzon Soho and inflict years of massive construction work in the heart of the theatre district). Much of the gentrification is due to plain greed overriding any kind of social commitment or social policy.

Rents are soaring and many small businesses are being forced out. My village is turning into Any City Centre Anywhere

Rents are soaring and many small businesses are being forced out. My village is turning into Any City Centre Anywhere, with identikit gimmicky pop-up hipster venues replacing cafes, restaurants, bars and shops that have been in situ for years. And it remains to be seen whether replacement music venues such as the “new” Madame JoJo’s when it opens in Walker’s Court will be able to provide a similar experience at similar, inexpensive prices to the old one. Our hardware store, which closed last week while a new hotel is built above it, will not be back in two years, having been told that its rent will have doubled, if not tripled, by then.

It was with all of this in mind that I became one of the founder members of Save Soho, whose call to arms is “Inclusive, not Exclusive”. In the short time it has existed, and thanks in no small part to the high profile of fellow committee members Benedict Cumberbatch and Stephen Fry, the organisation has focused attention on the impact of the area’s ongoing gentrification and already helped to chalk up a number of small but significant victories, such as saving Rupert Street’s historic Yard Bar from poorly conceived and destructive “development”.

No one opposes change. I hope my little history of the Soho I know and love demonstrates that this area is perfectly able to move with the times. But change cannot simply be about profit for a handful of people.

And if change results in the wholesale demolition of the very things that make Soho unique and original, rather than finding ways to respect and build on this unique square mile’s existing history and heritage, then I, along with my Save Soho colleagues, will continue to lobby and campaign as loudly as we can.

Colin Vaines is a film producer and long-time Soho resident. His latest production, Jake Chapman’s four part drama series The Marriage of Reason and Squalor, starts on Sky Arts on 11 June

The 1950s

Polly Perkins on… performing at the Windmill theatre

My father was an actor/manager at a club opposite the Windmill theatre; he worked for Paul Raymond sometimes. When I was 15 he told me: “Go and do an audition at the Windmill” and I did. I knew nothing about the place – I had no idea the audition would involve taking my clothes off. But there was an amazing atmosphere there; it was the warmest, kindest place. Everyone was really lovely and an older Windmill girl would show you what’s what. Iris, who took me under her wing, we’ve been friends all these years.

I didn’t have to take any clothes off for the first few months. I was 16 when I did. I was dying [of embarrassment] that first time; I’d always been very shy. The lord chamberlain wouldn’t allow a nude person to move in a theatre, so you had to stand very still. I had to do it reasonably regularly after that but I got used to it. It wasn’t all nudes; they had fantastic tap dances and ballets, brilliant performers and comedians… I can’t tell you how amazing it was. We had to be there at 11.15 in the morning and it went on till 10.30 at night. We’d do six shows in a day. A lot of people – well, they were all men – they’d stay the whole bloody day sometimes, with either a newspaper or a bowler hat on their knee; I’ll say no more.

We used to go to a cafe next door called the New Yorker to drink lemon teas, and the coffee bars: Heaven and Hell, Act One Scene One (that’s where the actors would go) and the 2i’s, where the rock’n’roll musicians were. Everybody there was in love with my friend Perrin from the Windmill. Tommy Steele wanted to marry her, so did Billy Fury. She was beautiful; the girls from the Windmill entered her into a Brigitte Bardot lookalike contest. They were like that, the girls.

The Kray twins would be up having a drink in Soho but whatever they were doing, it wasn’t happening in Soho

We’d go to Berwick Street market, where they had the barrow boys selling fruit, and they were absolutely lovely. It wasn’t all that whistling or anything suggestive, it was: “How you doin’, darlin’?” The Kray twins would be up having a drink in Soho but whatever they were doing, it wasn’t happening in Soho. You could talk to anyone – you can’t do that now. Even the girls at the strip clubs, they were all lovely too, you’d see them running up Old Compton Street with a little bag full of feathers…

We were very glamorous, but it wasn’t something we felt. We were self-critical, all of us. But the older girls were so nice to the younger ones, they’d help with the makeup and things; it was like a boarding school, where you danced and took your clothes off! Though not everyone did; Iris was too good a singer and they’d have lost her [if they’d made her]. But I was too young to argue and too grateful for the job. I started out on £12 a week in 1959 and every year I got a rise. When I left I was on £16-£17 a week, which was a lot of money then.

The Windmill theatre closed a couple of years after I left. I don’t think I’ve seen anything like it before or since. It taught me everything I know about my stagecraft; the discipline, getting on with people, dressing-room politics and the loyalty of friends.

Interview by Corinne Jones

Molly Parkin on… drinking at the Colony Room

The place in Soho that started it all off for me was the Studio Club in Swallow Street. I’d gone there with my friend Betty, with whom I was sharing a basement flat in Earl’s Court. She was very beautiful and fashionable and I was very arty. I used to wear black and put calamine lotion on my face, very pale, and lots of black pencil around my eyes. So there was a nonconformist look about me. All I needed was a slot to fit in. The Studio Club was a place for artists and jazz musicians and it had a tiny dancefloor and an amazing atmosphere to it. It was there I met [the illustrator] John Minton. He was gay and very beautiful and a wonderful dancer – and he was the first one to take me to the Colony Room.

The first time I walked up that narrow staircase I was horrified – it seemed to me so shabby and there were men with faces like I’d never seen before – very lived in, let’s put it that way. The place was rocking. The room was tiny and packed with photographs and bits and pieces and lumpy places to sit and the conversation was loud and the piano was pounding with jazz.

I took to the drink immediately, I couldn’t say no. When I came out on to Dean Street, I couldn’t even walk but I knew that an amazing life had opened up to me. The hangovers were appalling but it did enhance my creativity.

I became very close to Francis Bacon in the years between my marriages. He was so kind and attentive and funny.

I was very impressed by Muriel [Belcher, the famously rude owner], the way she used swear words in such a beguiling way. You’d bring in somebody that she had not seen before and she’d just look them up and down and say: “I don’t like the look of you cunty, fuck off.” Then she would wink at the rest of us and burst out laughing. She was a very handsome woman: she had a hooked nose, black hair drawn back from her face, very strong, dark eyes and, because of this “don’t care” attitude, everybody adored her. Francis Bacon was passionately in love with her.

I became very close to him in the years between my marriages. He was so kind and attentive and funny. One time he took me to the Golden Lion in Dean Street. Homosexuality was still illegal at that time but this was the place all the gay boys would go to when they arrived in London to meet kindred spirits. I remember Francis throwing all these £5 notes into the air and all the boys were scrambling for them, shouting: “Francis, Francis!” I’ve never seen such adoration.

I stopped going to the Colony Room in 1987 when I found myself in the gutter. I’m 83 now and I’ve been without a drink for 28 years, but those were my precious years. Every single moment that you were there was like being in heaven, because of the jokes and the laughter and the bonhomie. It was like lifeblood to me.

Interview by Joanne O’Connor

The 1960s

John Pearse on… working as a tailor in Carnaby Street

I left school aged 15 because I wanted to be in Soho. It was 1961 and my first job was on Wardour Street, upstairs from the Marquee Club, in a print factory. I was a lithographic artist, but I only lasted about eight weeks because I couldn’t stand the noise of the machines clunking. I wanted a calm job, so I thought I’d become a tailor and get some peace. And also I’d get the suit I wanted to wear that I couldn’t afford to buy. I decided I’d learn to make it.

There was a whole band of us, various peacocks parading around in sharp-as-a-knife tailoring. The Who, I think, Keith Moon, Brian Jones, people like that. We gravitated around the Flamingo Club, the Roaring Twenties and especially the Scene Club in Ham Yard, off Great Windmill Street. Of course the Stones played there, the Animals, anyone who was anybody was playing there. When Kennedy was shot in 1963, I remember they closed the Scene Club in honour of him that night.

Carnaby Street was a dirt track then, but there was John Stephen and Donis and these gay outlets, let’s say. They were the only places you’d get French imported stuff from – the hipster trousers and matelot shirts – which we liked. And the famous Levi’s shop was on Argyll Street, next door to the Palladium. You’d know if they had them in stock because you could smell the dye when you walked in.

When Time magazine ran its London: the Swinging City issue in 1966, Carnaby Street was gone up in smoke for us. It had become vastly overpopulated and commercialised by then; John Stephen had more or less the whole street and a lot of the indigenous little shops had gone. We were on our own route on the King’s Road in Chelsea, with our shop Granny Takes a Trip. My tailoring expertise served me very well over there and then Carnaby Street started copying all those things we were producing.

I stopped making suits for a few years – mostly working in film – but came back to Soho in 1986. I loved this building in Meard Street and I thought I’d do film production in the basement and sell a few suits to supplement my income. There was a pool table, so it was quite a clubby atmosphere, and for a couple of years I would have been the most exclusive, discreet tailor in the world, because you really had to know where to find me. It was all word of mouth; classic English tailoring, lots of vintage fabric. Jack Nicholson was a big client in those days, Hollywood people and Jagger, lots of different people.

I’ll stay in Soho until I get kicked out; I won’t get bored with it. It’s such a vibrant place and it always seems to evolve. It never stands still, so you either go with it, or you get off.

Interview by Tim Lewis

From the archive: George Melly on… the rhythm and blues invasion

Over the last year the British version of rhythm and blues has elbowed the Liverpool beat groups, always excepting the Beatles, out of the charts – and it looks as if it’s here to stay for a while.

Like most pop trends R&B started in the clubs, but it’s learned something. The top beat groups, and the top trad bands before them, priced themselves out of the clubs and played concerts only, but nearly all the R&B groups continue to play the clubs even after they’ve made the top 20. As a result they are holding their public and their music has not yet ossified.

British R&B today is a wide river, but it has two sources. One springs from traditional jazz, the other from modern. In Wardour Street are two clubs which could lay claim to promoting these tributaries. They are the Marquee on the traditional side, and the Flamingo on the modern.

The Marquee was originally in Oxford Street. In those days it featured all kinds of jazz but relied on trad to pay its way. Ironically enough, it was Chris Barber, the traditional band leader, who introduced the R&B viper into trad’s bosom. Interested in all forms of black music, he instituted in 1962 an experimental evening of R&B featuring Cyril Davis and Alexis Korner.

By the time the Marquee moved to Soho in 1964, the music was big enough to justify two evenings a week. On R&B nights at the Marquee it’s a very young audience and, if one of the groups gets into the hit parade, it’s a big one. It seems bright and lively, but they neither know nor care about the history of the music, only about its local heroes. An admirable policy of the Marquee is to bring over the great black blues singers whenever possible.

Up the road at the Flamingo there’s an older crowd. The Flamingo was one of the midwives of modern jazz in this country, but two and a half years ago an ex-Billy Fury sideman called Georgie Fame introduced a Sunday afternoon session of modern R&B, accompanying himself on the Hammond organ. A year ago the club moved over to an almost exclusively R&B policy.

This is an edited extract of an article that originally appeared in the Observer on 28 February 1965

Writer and agony aunt Irma Kurtz on… the search for bohemia

I came to London in the 60s in search of bohemia. I was escaping from the conventional destiny that was laid out for me in America, which was to marry a lawyer, maybe a doctor, in Connecticut, to live in the suburbs, have three children and two cars. I’d found it in the West Village in Manhattan and on the left bank in Paris and when a friend took me to the French House in Soho, I thought: “Thank heavens they have it here too.”

We use the word “bohemia” very easily but what it meant to me was an area where the affluent mix with the poor, where the gay mix with the straight, where long ago women could mix with men and be listened to. It’s a strange area of equality among people who are not generally considered equal and where celebrity is practically invisible. In bohemia, nothing matters but your conversation and your ability to talk to others.

The French House was everything I’d dreamed of. Everyone was leaning at the counter, no one was sitting down, everyone smoked, the mix was so welcoming. The main thing that bohemia had was a curiosity about newcomers, it wasn’t prejudiced against anyone, except of course fascists and bigots.

One of the hardest things for a young woman of any time to find is a place where she’s comfortable going in on her own. But it didn’t take long before I knew I was going to recognise people and I made a best friend, Jeff Bernard. He had a corner, his corner, and a circle of people around him, his court, because he was so funny. He wasn’t easy and he was a hell of a drinker and most nights I’d leave him to go back to where I was living in Shepherd’s Bush.

He once said to me: “Oh Irma, I’m so glad we never did the deed because it would have spoiled a wonderful friendship.” And it was.

If people were rude, if they were arrogant, if they were bigoted, they’d get them out

I was with him a lot at the end and so was Norman Balon, the landlord of the Coach and Horses. He was so good to Jeffrey. When he was bedridden, he kept him in food and made sure the flat was clean. He’s not a cheerful person, Norman, and he used to yell at people in the bar, but he was a good guy. There was a certain kind of bar person – characters such as Norman and Muriel [Belcher] – sharp-tempered, sharp-witted, they were the guardians of bohemia. If people were rude, if they were arrogant, if they were bigoted – things that have no place in bohemia – they’d get them out.

I stayed in Soho long enough to see the end of the great bars. I remember going into one of my favourite pubs and there was a television screen up, and I thought “uh-oh”. This was not long before I moved out. I remember thinking: “I’m not leaving Soho, Soho is leaving me.” When I go back now I’m very homesick for what it was. I don’t know where you go to find bohemia now. I asked one of my young friends and she looked at me and she asked me seriously: “Have you tried online?” JO’C

The 1970s

Keith Hehir-Lynch on… being a teenage ‘runner’ for a stripper

It’s 1973. There is an oil crisis in the Middle East. The IRA are blowing up anything and everything. Richard Reid the shoe bomber has unfortunately just been born and JRR Tolkien has unfortunately just died. There is a secondary banking crisis that causes negative equity in the housing market and the UK has finally admitted to being within 30 miles of the near continent and has joined the European Economic Community. A new value added tax has been stuck to everything, the Conservatives are in power and Sunderland only go and beat Leeds 1-0 in the FA Cup final.

It was against the backdrop of these events that I tripped and fell on a feisty and now angry stripper on a chilly and crisp November afternoon just off Soho Square in the West End of London…

After being told something clearly physically impossible to do by myself, I offered to carry her heavy bag as an apology. She accepted and pushed me into the club shouting at me to hurry the fuck up. I passed the big fat Greek doorman and followed her down the red-lit stairs. “Look after my bag,” I was instructed with a long red finger nail pointing within an inch of my eye. She also warned me not to move. So I didn’t.

Another reason I didn’t move was because I was in the second row of a smoky and dark, sparsely attended strip club watching a brightly lit stripper do what strippers do. As I hadn’t seen many naked women in the flesh, this became an instant highlight of the previous four days.

My next surprise was Cathy. A brunette, pale-skinned and curvy, full lips with the reddest of lipstick, was now wearing a blonde afro wig and on stage taking her clothes off to Walk on the Wild Side by Lou Reed. That song still stops me in my tracks at whatever I’m doing. I remember her perfectly arched back and fine arse moving and gyrating to it.

I felt compelled to make myself useful for the privilege of watching her unbelievably perfect bottom and picked up the knickers and basque thrown to the side near the front of the small stage and I put them in her bag. Within minutes, Cathy the stripper, now minus the wig, was marching towards me on the way out of the door. She grabbed the bag I was holding and sped off past me. I followed her out.

She watched me collect her outfit and gave me 50p, thanked me and rushed off. I ran after her and asked where she was off to next. She was already speed walking to another strip club 100 yards up the street, one of about 15 or so she would perform in rotation most nights.

So the deal was done. Cathy often called me a cheeky little bastard, but I got £2 a night from her and in turn saved her money buying new outfits because either the top or the bottoms were nicked during a performance by the other girls or snatched away by paying punters wanting souvenirs. I was a goalkeeper of knickers, the comedic fighter of old men to rescue a bra. I even ended up on my arse on one occasion with two old men fighting it out over her black satin knickers. I say “old”, but anyone over 30 would have been old to my 14-year-old self.

I’d like to think she regales her grown-up children with tales of her exploits today. Maybe she tells the tale of a young man who she once paid to pick up her knickers. Maybe she has never ever told a living soul of her life as a stripper. Maybe...

@Mr_Taxi_Man

Chris Sullivan on… the best nightclubs of the decade

I’ve probably spent more time in Soho than any other place on Earth. My first visit was to Crackers nightclub on Wardour Street in September 1975, aged 15. With its exceedingly flamboyant gay, straight, black and white clientele, united by their love of US underground funk music, there was nowhere like it in the UK and, as I soon discovered, exactly the same could be said of its locale.

Subsequent trips further fuelled my enthusiasm. We caught an early Sex Pistols gig in the El Paradise strip joint on Brewer Street in April 1976, imbibed chemically enhanced punch and lost ourselves, only to resurface the next afternoon on a bench in Soho Square. After that came Louise’s, the Sapphic nightspot on Poland Street that we, at first, thought a rather straight disco full of blokes in suits, before realising they were all women. Accordingly, they didn’t bat an eyelid as the Sex Pistols, the so-called “Bromley contingent” and assorted bondage-clad youth invaded their club.

Soho was the only place for us. Nowhere else would have us

In October 1978, my old partner in crime, fellow Welshman Steve Strange, invited me to his weekly Bowie night at a club called Billy’s on Meard Street – a tiny paved street full of street walkers, red lights and brothels. The club, replete with sticky carpets, foul toilets and bad drinks, was usually populated by hookers, androgynous rent boys and moody gangsters. On a Tuesday, though, it was given over to our gang of former punk-rocking Bowie fans – among them the likes of Boy George, Marilyn, Siobhan Fahey, Marc Almond and Philip Sallon – who, with a newfound love of electro music, would soon put the cat among the pigeons. In truth, Soho was the only place for us. Nowhere else would have us.

The following year, I was accepted into Saint Martins College of Art on Charing Cross Road to study fashion. For many, Saint Martins was as much about the social life as it was about studying and Soho was thus enriched by the students, especially the fashion brigade, who sucked the lemon dry. We’d spend lunchtimes in the French House or the Duke of Cambridge (or my favourite, Ward’s Irish House beneath Piccadilly) and hang out with actors and journalists and then, when the bars shut at 2.30pm, we’d try and wangle our way into the morally decrepit Colony Room on Dean Street. The image of Stephen Linard in gold lamé Elvis suit, bleached quiff and eyeliner next to Kim Bowen, with her foot-high Stephen Jones head-dress and silent movie star makeup, propped up between Francis Bacon, Molly Parkin and George Melly, is not easily forgotten.

Above all, Soho was hilarious. One lunchtime I saw two thoroughly androgynous male Saint Martins fashion bods come to blows over a piece of gold lame in the bargain bin at Borovick Fabrics. Jeered on by the market lads, the fight was broken up by a middle-aged prostitute who looked like a chemically abused Diana Dors.

When too broke to hang out in pubs, we students would often duck into the Academy arts cinema on Oxford Street and catch Scorsese’s Mean Streets and Truffaut’s 400 Blows for a couple of quid, while book shops like Foyles fulfilled one’s every literary need. It was against this backdrop that I opened my own Monday-night soiree in 1980 at the St Moritz, with Robert Elms, Graham Smith and Steven Mahoney, which was packed from day one. Subsequently, I partnered Steve Strange and Rusty Egan for a club called Hell in Covent Garden, did a long-running Tuesday at Le Kilt in Wardour Street, and then in 1982 opened the Wag at 33 Wardour Street, which I ran for 18 years.

Soho was then a dodgy red-light district, which was why so many of us were given nights to run. Soon they blossomed all over Soho, playing soul, funk, reggae, African music, goth, punk, mod, electro, Latin and jazz, and the area was jumping again. Young bands, DJs, graphic designers, painters, artists, film-makers and poets all found clubs in which to display their wares and every night of the week there’d be a handful of after-hours pubs that serviced trendies, trannies, hookers, villains and plain old club workers.

After the Wag came Soho Brasserie, the Groucho, Soho House and the march of haute cuisine, which – always the first sign of an area’s creative decline – is followed by gentrification, increased rents and a general loss of soul, all of which many of us are fighting against.

Soho is the pulsing Queen Bee of London. We have to look after it.

The 1980s

Peter Dowland on… being one of the young guns of hairdressing

I joined Cuts in 1985, aged 21, just after it moved from Kensington Market to Frith Street, next door to Bar Italia. We were the first anti-salon. Even just walking past, it looked so different. The energy in there was crazy – Boy George called it “a community centre for weirdos”. David Bowie came, Boy George, Neneh Cherry, Jean Paul Gaultier. Bros were sent to us by their record company. They had perms and long hair and we just shaved it all off and gave them quiffs. It produced tears on the day. But no one was ever treated any differently. Maybe Michael Hutchence would ask to have his hair cut in the basement to avoid the paparazzi. But once down there, we’d just hang out. Everyone was really into the music; we’d be avid consumers of the latest beats and hip-hop from America. We’d always be the first guys to have it, so there was a real energy of discovery all the time.

Cuts’s original founders James Lebon and Steve Brooks were part of the Buffalo fashion collective. It was a synergy of like minds working in design, music, photography. They consistently put out groundbreaking images: macho but camp, feminine but hard. I told them I wanted a job assisting the stylist Ray Petri who created the Buffalo Boy look. James suggested I start by cutting hair with them. And 30 years later I’m still here.

At first we just rented two chairs – the other hairdressers were two old Italian boys. But we got busy pretty quickly. We were the young guns. The whole film industry and nightlife was here. It was the can-do era. People would go: “Right. I’m going to be a video director” and just do it on whatever budget you could scrape together. Everything felt possible. Music was about two turntables and a drum machine – using other people’s records as instruments and repurposing them. It was creative salvage, a bit like Tom Dixon’s furniture. We had loads of his pieces in the shop – magazine racks made out of manhole covers.

It wasn’t contrived cool. It was just the chemistry of the people who were there

Things weren’t exposed so quickly, so you were able to build your thing without being in the glare of the media. I think kids have a hard time now – whatever little thing they’re getting into is up online having the life sucked out of before it’s even had time to learn to walk.

People tell me it was really intimidating going into the salon for the first time – but as soon as you were through the door you realised everyone was very nice. It wasn’t contrived cool. It was just the chemistry of the people who were there. Hairdressing had a very set image then and James and Steve wanted this quite hetero, sexy feel.

The downside now is that every hairdresser has full-sleeve tattoos and looks like a Hells Angel. When I walk round Shoreditch, I think: “Gosh, we’ve created a monster.”

Interview by Liz Hoggard

The 1990s

The Very Miss Dusty O on… Madame Jojo’s nightclub

I came to London from Birmingham in 1989 and got friendly with these people who ran a big club, Bambina’s. They asked me if I’d do the door in drag – it was a fairly new thing at the time and created quite a stir. I’d change my look from day to day: waist-length green dreadlocks one day, the next a shaved head and full makeup. One day, their DJ didn’t show up and I was asked to DJ in the VIP room. I drifted into it, really, and ended up working at places like Bang, Fred’s, the Village, and the Ghetto, which has now been knocked down to make space for that hideous, monstrous Crossrail thing.

Soho became very gay very quickly: in the 90s I’d say it was 90% gay on certain streets. It was a safe place: if you wanted to hold your boyfriend’s hand you held your boyfriend’s hand. I could walk down Old Compton Street in a bikini and no one would bat an eyelid. The crowds were a mixture of the out and fashionable with the underground and sleazy, celebrities mixing with prostitutes, punks and pimps. Everybody was thrown into the melee: it wasn’t corporate, it wasn’t mundane. Now it’s becoming like a creme brulee – bland, all one colour – whereas in those days it was more like a trifle, colourful and glittery.

Madame Jojo’s was of huge importance to me. Trannyshack, which was the Wednesday nights I ran there, was a very significant part of my life. If you weren’t from London and you imagined what Soho was, that’s what Trannyshack was: a mixture of everyone, gays, straights, drag, transgender, punks, hipsters, pop stars. We never had to advertise. It was a bit like going back to Berlin in the 30s.

All sorts of things used to happen – Grace Jones dancing on tables, Jean Paul Gaultier and Donatella Versace doing the conga in the road outside – it was a very special place. Soho will be more magnolia for its loss.

I think the gay scene has changed. In those days, because there was no internet, if you wanted to be part of a movement you actually had to go to these places. Now all you have to do is click on Facebook to find out exactly what’s going on: you can live almost a fantasy life. I was upset to see Soho change, but other things have arisen in different areas. East London caters for the alternative side of clubbing, with venues like East Bloc and the George & Dragon; Vauxhall caters for the more mainstream muscly gays who want to dance to house music.

When Jojo’s closed last year it was the final nail in the coffin for me. I’d become gradually more disillusioned with the area. I’ve reached my mid-40s, I’m settled down with someone, and your interests change, don’t they? People often say to me: “But you were the queen of Soho for all those years.” Well, yes, and when I left it was my choice. I wasn’t pushed – I abdicated.

Interview by Kathryn Bromwich

John Maybury on… illegal after-hours clubs

One of my great friends and mentors was Derek Jarman and Soho was very much his stomping ground. It was Derek who introduced me to the basics, like going to Berwick Street market, or to Chinatown for a cheap bowl of char siu. There would be all these different worlds that intersected there.

You might luck out and some old queen would take you to L’Escargot for dinner, and there were always different after-hours clubs, such as the Pink Panther. People like Leigh Bowery used to go there – this was when he was just a weirdo on the scene. I won’t go into what sort of things went on in there, but we were regularly raided by the police and everyone would drop everything they had, so there would suddenly be a carpet of substances on the floor and everyone would be marched out on to the street and then, half an hour later, everyone would march back in again and pick up everything they’d left on the floor.

Places like that were so transient: they were there and then they were gone. The place I miss most has to be the Colony Room. I was first taken there as a young punk in the late 70s by the painter Michael Wishart. Francis Bacon was there and I was terrified of him. I had dyed hair and makeup, and, ironically, so did he.

A lot of the old Colony crowd resented the imposition of gay culture, because they saw themselves as queers, not gays

He was very much a hero, which is why I made the film Love Is the Devil. 1995, when I started working on it, was a really interesting time [at the Colony Room] because there was a sudden change of the guard – you still had a lot of the crowd from the 50s and 60s, as well as people such as Sarah Lucas, Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin.

Soho is always mutating. Back then, people moaned about the influx of gay clubs, saying that was a kind of gentrification. Old Compton Street turned into something they didn’t recognise in the 90s. A lot of the old Colony Room crowd resented the imposition of gay culture, because they saw themselves as queers, not gays. They existed at a time when being gay was illegal and they found the gay scene contrary to their code of being.

But what’s happening now is a whole other ball game; places disappear almost overnight. What’s great about London, though, is that despite the property developers, people will always find a new place to gravitate to and then the gentrification virus will creep into that area as well.

Margot Henderson on… the French House pub and its atmospheric dining room upstairs

Fergus and I met when I was working at the Eagle [in Farringdon] and he was working at the Globe in Notting Hill. We fell in love and decided we wanted to open a restaurant together. He had a friend called Jon Spiteri, who said that there was space above the French House pub in Soho. We were all regulars, so John spoke to Lesley and Noel [the proprietors] and they were very keen. The three of us were partners there from 1992 before Fergus and John went off and did St John together in ’95. It was a bit upsetting, but Mel [Melanie Arnold, John’s wife] and I became great partners, and it was all for the best. We had all our small children there and manned the French for seven to eight years. We loved it there – it was our baby.

Damien Hirst did his first skull, Sarah Lucas did a piece – it was all very exciting

It was a gorgeous pub full of atmosphere, with some great characters. We really felt a part of it. The dining room was small and intimate, we had people proposing there, we had funerals, marriages, everything. We started to do a lot of art events: White Cube had a lot of their dinners there – we did a dinner for Nan Goldin. Mel was living in Broadwick Street and I was in Covent Garden, so we would bring our little kids into the restaurant every day and it was very much family-based; we knew everyone on the street. The woman who used to clean the spanking-mag shop next to Patisserie Valerie used to give all the kids teddy bears. Everyone just knew everyone, it had a real village atmosphere, and I think the French House dining room brought that with it as well. Lucian Freud would come up and sit in the kitchen and flirt with all the young chefs… Lots of artists came, all the local naughty people – people who love to eat and drink and have long lunches.

Our three children all went to Soho Parish primary, a really lovely school in the middle of Soho. It was very small, and really suffered from funding, so Mel and I had an art auction for it at the Groucho and sold £180,000 worth of art, which everyone was in absolute tears about – it was pretty amazing! Damien Hirst did his first skull, Sarah Lucas did a piece – it was all very exciting.

Bar Italia was very good with children; it’s been our place for ever. I think it saved me, actually. Every morning, I’d head straight there and read all the papers with a baby on my front before going into work.

We were very sad to leave. We put our hearts and souls into it and we didn’t mind not making lots of money. It was just so hard not to have a business in Soho. There’s an atmosphere of people looking out for one another there; it’s a friendly, happy place.

The 2000s

Michele Wade on… Soho’s cafe culture

I’ve been involved in Maison Bertaux since I was about 17, in the late 70s. I fell in love with Soho, but especially in love with the shop, the whole atmosphere. I started as a Saturday girl, then I was a waitress and then I went to study at Rada. I made a little bit of money in acting, so when Mme Vignaud, my boss, said she wanted to sell the business, I bought it from her. I was 25 or 26.

There weren’t so many places in Soho then where you could have tea, coffee, conversations. The pubs used to close between 3 and 5pm, so we got a slightly different clientele because of that… I remember Jeffrey Bernard used to come in sometimes after drinking at the Coach and Horses at lunchtime. He’d sit upstairs and fall slightly asleep in his chair and then go to the pub again afterwards. We also used to have the art school [Central Saint Martins] up the road and the students used to come here to sit upstairs and draw… it was relaxing for people. Alexander McQueen was a real regular, just gorgeous. We knew him quite well.

Now my sister, Tania, and I run a little art gallery upstairs. We’ve got Noel Fielding’s artwork up there, he’s really charming. Clients? We’ve had all sorts: Derek Jarman was always coming here, he was a marvellous person; Steve McQueen, Howard Hodgkin, Grayson Perry…

In Soho, there’s space for everybody – other burgeoning areas aren't as inclusive

The big thing of Soho is the freedom for people to be who they are. I’ve got a [male] customer who comes in dressed as a woman and no one pays any attention. I think people worry the corporations might squeeze down that freedom. In Soho, there’s space for everybody, but other burgeoning areas – like Shoreditch, Dalston, Peckham – they’re not as inclusive. Maybe that’s why a lot of businesses can coexist in Soho.

We’re frightened about the rent going up so high that we can’t afford to be here, but I try never to be scared. When I first took over Maison Bertaux, we only did one type of tea, but now we do about 20; we only did cafe au lait, but now we do all the coffees. Soho is always changing and you’ve got to adapt and be attractive to people who are enjoying the change. But people have to help each other to make sure there’s room for everyone.

The vicar from the church nearby comes to get his ham-and-cheese croissant every Saturday and Sunday and we’ve got a lot of irregular regulars from all over the world who come to Maison Bertaux when they’re in London. We also have quite a few people coming in who aren’t homeless, but who’ve fallen on hard times, so we give them something to keep them going.

Soho’s always had that history of having different kinds of businesses and restaurants, and I think that’s what makes it unique, because every building’s had a restaurant in it before and before that and before that… Everyone over 40 who knows Soho, they’ll have a memory of it. People won’t have those memories of Hoxton, or places like that. CJ

Tim Arnold on… why we started the Save Soho campaign

I got a place at St Martins to study fine art in 1994, but then I got snapped up for an eight-record deal by Sony. I never went to art school. I was living on Charing Cross Road, Sony were on Great Marlborough Street and I was going to places like Cafe Bar Sicilia, the Atlantic Bar and the Astoria, so Soho was my world. I was hanging out with people like Jarvis Cocker and Alex James from Blur.

In 2010, I decided to write a book, called Soho Heroes. I’ve interviewed over 100 people: tailors, restaurateurs, DJs, remarkable characters I’ve worked with and lived alongside all these years. And then I started working on a concept album, The Soho Hobo, which is really just me trying to understand what it is about the place that I love so much. As I was working on those two projects I kept seeing Soho disappearing bit by bit.

And then Madame Jojo’s closed and I realised it isn’t enough to sing about Soho any more; you’ve got to do something. That’s when I wrote to Boris Johnson and enlisted Benedict Cumberbatch who in turn enlisted Stephen Fry to sign the letter. I set up the Save Soho website so that people who felt the same could come together, and then suddenly we were getting 25,000 hits a week.

Young kids want to walk down the street where the Rolling Stones recorded, they want to possibly bump into Jimmy Page

It’s hard enough for new artists starting out, without the small venues closing down. And with somewhere like Denmark Street, young kids want to walk down the street where the Rolling Stones recorded, they want to possibly bump into Jimmy Page buying a guitar. They want to have that feeling that I had when I was in Madame Jojo’s and rubbing shoulders with the likes of Jarvis Cocker – “I must be in the right place because all the guys who inspire me are here.” There’s a passing of the baton and, culturally, there’s a responsibility to keep those venues inclusive and let them continue.

For 400 years, Soho has allowed people to think differently, from Karl Marx, who wrote Das Kapital in Dean Street, right up to Paul O’Grady, who was doing the kind of comedy that would have got him thrown out of any other place in England. It’s a national platform for innovation and creativity, and it’s under threat from people who want to turn it into a rich person’s playground.

As a singer-songwriter, I have been ignited by the spirit of the area. I write at least a song every day and I usually do it looking out of my window in Frith Street. I’ve led a very bohemian life, sacrificing everything that’s respectable for creativity. I wouldn’t have had that life anywhere else. JO’C

Laurence Lynch on… much-missed institutions

There is an energy in Soho that sends people mad. When I first moved to Soho about 25 years ago, it was not only the madness that interested me, it was the small independent business people; they still do, the grafters who keep our community alive with their warm welcomes and industry. I love pubs and that was where I was able to meet people, make friends and pick up work. It was all word of mouth – that was how Soho worked.

After many years, I was taken to the Colony Room, 41 Dean Street, where I became a member. To me, it was the centre of the centre. I spent a year of my life with Sebastian Horsley, Hamish McAlpine, Ian Freeman and others trying to save it. Change of use was turned down, but the landlord appealed and now the Colony is a one-bedroom flat. It is not the only Soho treasure lost in the past 10 years. Here’s a roll call:

The New Piccadilly restaurant in Denman Street, voted the joint best cafe in London, demolished to build the Ham Yard hotel complex.

The Bath House pub, Dean Street, demolished, Crossrail.

The Black Gardenia, Dean Street, demolished, Crossrail.

The Astoria music venue, Charing Cross Road, demolished, Crossrail.

The Intrepid Fox, Wardour Street, world-famous rock pub, now a burger bar.

The Devonshire Arms, Denman Street, now Jamie’s Italian.

The Soho Pizzeria, Beak Street, now a burger bar.

The King’s Head and Dive Bar, Gerrard Street, demolished, Chinese restaurant.

The Lorelei Italian restaurant in Bateman Street, there for about 40 years, replaced by a restaurant that lasted six months.

And now it’s the turn of Berwick Street market’s adjoining shops, which are being destroyed to make way for another hotel. Lastly – for now – the plot on which Curzon Soho cinema stands in Shaftesbury Avenue is now being eyed up for Crossrail 2.

That is a lot to take out of a small area in such a short time. The living thing that is Soho is having its limbs removed. But we’re not ready to put the keys back through the letterbox and turn the lights out yet. Now, whose round is it anyway?

Laurence Lynch is a playwright and plumber. His play, Burnt Oak, runs until tonight at the Leicester Square theatre

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion