This article, Fleet Street at closing time by Peter Corrigan, was published on 6 March 1988 in a special 12-page supplement dedicated to the Observer’s move to Battersea in south west London

Picture a ghost town in the Wild West – ramshackle buildings, tumbleweed blowing down the dusty street, saloon doors swinging forlornly in the wind. If a rheumy-eyed old journalist stands in Ludgate Circus and looks around, that’s what he will see in future... especially the saloon doors.

There are many things to be missed about that sprawl of newspapers and newspapermen called Fleet Street. But the pubs we are leaving behind will make the hangover last longer. If this suggests an abnormal preoccupation with the licensed trade, then we are in danger of giving a misleading impression of Fleet Street’s dependence on alcohol.

The stuff cannot be ruled out, of course, as Mr Rupert Murdoch discovered in his early days as a newspaper tycoon. Mr Murdoch – not a lover of drinking at or even near the job – suffered an early disappointment at The Sun when he opened a door on a group of tired news executives, dousing the fires of the day with the only vessels they could find – large brandy glasses. The shocked Murdoch swiftly closed the door and said aghast to an aide: “They’re drinking my scotch out of goldfish bowls in there.”

While the delicate sensitivities of some are not suited to all aspects of journalistic life, we are dealing here with a historic association that defies crude and simplistic assessment. The public houses, wine bars and afternoon drinking clubs that glow invitingly in the darkest corners of the Fleet Street area contributed far more to the fabric and energy of the place than a mere slaking of the hearty thirst journalism creates.

Unfortunately, stories get handed down that prevent the sympathetic understanding of Fleet Street’s needs in this respect. That great journalist Hannen Swaffer was once returning from his lunchtime refreshment while he was editor of the Weekly Despatch when the steps of Northcliffe House confused his feet. As he fell, the figure of Lord Northcliffe appeared at the top of the steps. “Mr Swaffer,” he said, “there are far too many drunkards working for this newspaper.” “Quite right, sir,” said Swaffer, rising to his feet. “I’m just on my way to sack a few.”

But this fine industry, which for so long has served the entire nation with some of the world’s great newspapers – and others – from this tiny patch of London, has received more help than hiccup from the many licensed premises so close to hand.

For the journalists and allied tradesmen on whose sweat that service has been built, the office local has been an oasis, intensive care unit, ego massage parlour, moneylender, bureau de change, job centre – everything the hard-pressed could wish for. A reporter could get the sack in the morning and know exactly in which pubs to start trawling for a new job that very lunchtime. An editor bent on poaching a rival’s star performer could arrange for his quarry to be casually ambushed at a place and time when his resistance would be lowest.

First-aid stations

It was something more than an extension of the newspaper: for some a home from home, for others an air-lock between the desk and suburbia. A man could get the bends going straight from one to the other. Not all journalists get on with each other, so each office pub would have a few satellites to accommodate political overspills. Most of the Daily Mail staff, for instance, use the Harrow, while others frequent the Mucky Duck, as the White Swan is traditionally known, or the Welsh Harp, which once housed a glum group of Mail men known as the Fingertip Club, because that best described how they were hanging onto their jobs.

The men and women running these first-aid stations were also very special, sent from some training school in the sky – drilled not only in the dispensary arts, but in treating victims of the world’s calamities. Alan Drew is typical of these ministering angels. He keeps the Harrow, a split-level pub in the aptly-named Hanging Sword Lane, and as much part of the Daily Mail as the proprietor’s wife.

Alan is shortly to retire after 44 years at the Harrow and of the many stories of his reign, his relationship with the great Mail writer Vincent Mulchrone will be remembered longest. A silent cameo was often enacted between them. At the crack of opening time Vincent would enter, accompanied by a thick head. Wordlessly he would lift three fingers and, without a flicker of recognition, Alan would put three glasses on the bar. In the first he would pour a stiff measure of Fernet Branca, the hangover cure, in the second went plain water to take away the taste of the Fernet Branca and in the third went to champagne... This is the sort of considerate care that has nurtured many Fleet Street favourites, enabling them to withstand the harshness of the life and survive the many crises to which the creative brain is prey.

Naturally, The Observer has needed more than average attention in this direction, the standards expected of its staff requiring specialised encouragement. Fortunately our previous home was in a corner of the Fleet Street area, which, once the Times lot left for Gray’s Inn Road a dozen years ago, was mercifully a few hundred yards from the throng, so one could choose from four or five hostelries without tripping over rivals, except the odd glazed stranger from the nearby Financial Times.

The Blackfriar was once a favourite, with its large hearth and beautiful bronze friezes depicting daily life in a monastery. Cruelly, the frieze above the bar was entitled “Tomorrow will be Friday” – the day Sunday newspaper writers have to produce the words which may or may not justify their existence. It was at the Blackfriar that I achieved the ambition of most newspaper men by actually living there for two years as the guest of Barry and Nancy Lloyd, jovial and generous hosts indeed.

It was also at the Blackfriar that a predecessor perfected the balance between office and pub by using the pub as his office. He found it much more convenient to meet the many people vital to his job at his alcove table in the Blackfriar. Applicants, supplicants and communicants were each given an appointed time and waited patiently at the bar until called into the presence. As most of the interviewees brought him a large one it was a viciously demanding working lunch, but his pages will testify it was very effective.

Various departments of The Observer had their own favourite places of rest and recuperation, but the most popular by far to all and sundry was the Cockpit, which actually was a corner of The Observer building. If you had taken away the Cockpit, The Observer would have collapsed in more ways than one. As it happened, The Observer was taken away from the Cockpit, but the number of pilgrimages already made back there from Battersea testifies to its magnetic pull on our souls. Apart from its historic setting and welcoming cosiness, the Cockpit owes much of its attraction to the long-reigning landlords Liam and Sheila O’Callaghan, whose ready smiles and patient ears repaired the ravages of many a desperate day.

Sheila is usually on the working side of the bar and Liam on the other, rallying the customers. He keeps the best pint of Guinness in London and it comes with a head so thick and creamy you could, he boasts, walk a mouse across it. Liam has created a legendary reputation among the walking wounded for his generosity and is probably the only publican in the UK who is also his own best customer, often willing to wrestle you for the privilege.

In common with most other Fleet Street landlords, Liam is willing to cash cheques, which often gives the illusion you are leaving with more money than you went in with. Some took more advantage than others of this service, indeed at one time my bank manager thought Liam was blackmailing me. Taking leave of Liam and Sheila was for many of us one of the biggest wrenches of our lives – a touching farewell that has been and will be repeated all over Fleet Street.

When Murdoch took his newspapers from Fleet Street to Wapping in that notoriously sudden move, the farewells were brutally abrupt. Too many thousands were left jobless by that exodus for any sympathy to be available for the publicans left behind – but just imagine running an establishment frequented by the Sun or News of the World and losing overnight the most lucrative thirsts in Britain.

Land of the legless

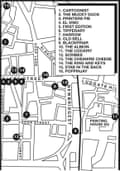

It was the fate suffered in varying degrees by the Tipperary, First Edition, Printers Pie, Coach and Horses and several others, including Ye Olde Cock, which was the haunt of the News of the World sports desk and I refuse to make any comment. The Telegraph have vacated the narrow comforts of the King and Keys, the Times have quit the Packenham.

But it is not yet all over. There are still large pockets of resistance, particularly around the Mirror building in Holborn. The Mirror Group always had the largest pockets and a reputation for using them vigorously amid the bright lights and tinkling pianos. So much so that when Clive Thornton became chairman five years ago it was noted he had an artificial leg. The observation flashed around the Street - “In the land of the legless the one-legged man is King.”

We know not how long the Mirror newspapers will remain to hold firm control over the pubs to the north of Fleet Street. The nickname of the Mirror’s main pub indicates another use made of such establishments: “The Stab in the Back”, a name so entrenched it has eclipsed the original name of the White Hart.

While the Daily Mail waits to move to Kensington, its great rival the Daily Express is tasting the last lingering pleasures available in the Poppins, the Old Bell and the Punch, before heading for its new home on the other side of Blackfriars Bridge.

But not all Fleet Street’s pubs and bars have been linked exclusively to one newspaper or another. There was much neutral bar space, alcoholic Switzerlands, where rivals could mingle. Some newspaper people like to take food with their meals and there were few places better than the Albion, which stands at the south-west corner of Ludgate Circus, where Mickey and his wife Rhona and the late, lamented Joan dished up the finest steaks nearby Smithfield could produce.

At the other end of the Street, no doubt influenced by the strong presence of the legal profession, the premises are more up-market, notably the Wig and Pen club. At this end, too, is the famous El Vino, which was not the favourite of this rank and file because beer is not among its inducements. But those with the ability to drink and think at the same time have gathered for generations to sit around old tables and lubricate their eloquent conversations with the finest champagne or claret.

El Vino, in common with the pubs, has the annoying habit of pitching customers out between the hours of three and five in the afternoon, a gap that was filled by an outbreak of clubs, including the Press Club. Someone also had the bright idea of introducing a golf club. The premises contain a large screen onto which was projected a fairway. Golfers would drive the ball against screen and be told how far down the fairway it would have gone. The curious turned up in droves but were soon distracted by the clinking of glasses from the club bar. Pretty soon cobwebs began to appear on the screen and it was eventually cleared out to make room for another bar. It has now disappeared, many of its clientele happily served in the afternoon at Scribes.

Now, as the exiled newspapers comb their new areas for such havens and shelters they can find, the memories are hard to bear. Let us content ourselves by sharing the enlightenment experienced by a former news editor of the Sunday Times, coincidentally at this time of year. He was leading his colleagues back to the office after a lunchtime session when he suddenly stopped. “It must be getting near springtime, lads,” he cried, “We’re going back in daylight.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion