Download ebook with full colour photos (larger size - Travel Magpie

Download ebook with full colour photos (larger size - Travel Magpie

Download ebook with full colour photos (larger size - Travel Magpie

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

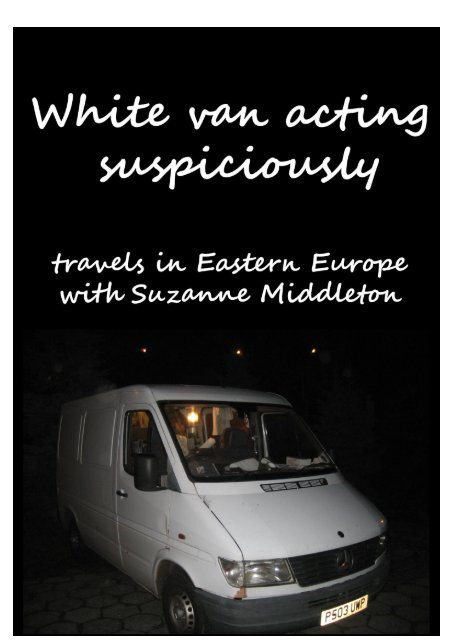

White Van Acting Suspiciously<br />

<strong>Travel</strong>s in Eastern Europe <strong>with</strong><br />

Suzanne Middleton<br />

Photography<br />

John Robilliard<br />

Publisher Suzanne Middleton<br />

www.travelmagpie.com<br />

Copyright © Suzanne Middleton 2011<br />

ISBN 978-0-473-18290-8

Contents<br />

Map of the Journey .................................................................................................................... 4<br />

Chapter 1 France, Belgium, Netherlands ................................................................................... 5<br />

Chapter 2 Germany .................................................................................................................. 15<br />

Chapter 3 Germany, Czech Republic ....................................................................................... 28<br />

Chapter 4 Czech Republic, Germany ....................................................................................... 45<br />

Chapter 5 Poland, Slovakia, Hungary ...................................................................................... 60<br />

Chapter 6 Romania ................................................................................................................ 104<br />

Chapter 7 Bulgaria, Turkey .................................................................................................... 149<br />

Chapter 8 Turkey ................................................................................................................... 199<br />

Chapter 9 Greece.................................................................................................................... 247<br />

Chapter 10 Italy, Croatia, Bosnia-Hercegovina, Slovenia ..................................................... 302<br />

Chapter 11 Italy, Austria, Switzerland, France ...................................................................... 343<br />

Epilogue ................................................................................................................................. 395<br />

Bibliography .......................................................................................................................... 396<br />

Photos of Suzanne and John .................................................................................................. 398<br />

Thanks .................................................................................................................................... 399<br />

3

Map of the Journey<br />

4

Chapter 1 France, Belgium, Netherlands<br />

31 July – 16 August 2008<br />

Known Unto God<br />

In Dover we ceremoniously record the van‟s mileage - 155,576 - before driving into<br />

the hold of the Norfolk Line ferry in a state of exhilaration. A glorious year of freedom<br />

stretches ahead of us, loosely defined and unpredictable.<br />

We‟re off to Eastern Europe, Turkey and Greece in an old builder‟s van <strong>with</strong> a<br />

mattress, gas cooker and toilet in the back, knowing that the trip will change us forever.<br />

Unable to resist a moment of cliché we go up on deck and take pictures of the receding white<br />

cliffs.<br />

An encounter <strong>with</strong> a Romanian Big Issue seller in Dover the day before has added to<br />

our elation. He was blown away to hear that we were driving to his homeland and wished us<br />

an emotional farewell.<br />

With dozens of travel guides and road atlases stashed away, a compass on the<br />

windscreen, some jars of curry paste and New Zealand Marmite in the pantry, if we‟ve<br />

forgotten anything it‟s too late now. Our lack of suitcases, bookings and satellite navigation<br />

is liberating.<br />

In Dunkirk we park for the night on the promenade at Malo-les-Bains. Low tide has<br />

exposed wide sand flats where a rugby team is training. It rains off and on from a black sky<br />

as the locals promenade and cycle past.<br />

All our planning and lists are history. We have no commitments. We‟re on fire.<br />

By the next morning we‟re unwinding. After a leisurely breakfast we head south east<br />

into Belgium towards Ypres, through summer fields of wheat, barley, potatoes, maize and<br />

Brussels sprouts. We travel past white cattle, mares and foals, along avenues of oaks and<br />

maples. It‟s a flat, green and orderly landscape of shuttered farmhouses and canals.<br />

We have a sense of trepidation about Ypres, a medieval town which was completely<br />

destroyed in WW1, but we discover that it‟s been lovingly rebuilt, <strong>with</strong> a leafy car park in the<br />

centre of town where we can stay. The wide city ramparts incorporate sections of moat <strong>with</strong><br />

lawns, beautiful trees, and gardens.<br />

First of all we visit a tiny Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery which<br />

has the graves of fourteen Kiwi soldiers, including eleven from the Maori Battalion. The<br />

headstones of unnamed soldiers have the words “A Soldier of the Great War ... Known Unto<br />

5

God”. A father <strong>with</strong> a Manchester accent explains the meaning of this to his son, then points<br />

to one of the graves and says, “He‟s a Maori”.<br />

The Menin Gate is a huge Roman style triumphal arch erected by the Brits on the site<br />

of the town‟s medieval east gate, on the road where thousands of soldiers marched on their<br />

way to the front, as a memorial to honour fifty five thousand British and Commonwealth<br />

soldiers whose bodies were never found. Their names are all there, so many Canadians and<br />

Australians, and some Indians. There is only one New Zealand name, in <strong>with</strong> the British. At<br />

8pm there‟s a crowd of a few hundred to hear five buglers play “The Last Post”, a nightly<br />

ritual since 1928, suspended only during the German occupation in WW2. The solemnity<br />

and sadness of the occasion are a fitting start to our journey. We will be constantly reminded<br />

of grim historical events in the months ahead.<br />

Next day we drive into the country and visit Tyne Cot cemetery. Tyne Cot was the<br />

name that homesick Northumbrian soldiers gave to a little farm building on the site. The<br />

cemetery is enclosed by walls of flint and contains 12,000 graves, including those of 520<br />

named and 1,166 unnamed New Zealand soldiers. Like all the Commonwealth War Graves<br />

Commission cemeteries, it has immaculate headstones, and abundant flowers and shrubs.<br />

Dwarf junipers mark the end of each row of graves, <strong>with</strong> roses, daisies, alliums, heather and<br />

dahlias in front of the headstones. A huge curved wall is inscribed <strong>with</strong> the names of soldiers<br />

whose bodies were never found. We‟re intrigued by the names of some of the regiments:<br />

London Cyclists, London Artists.<br />

Tyne Cot Cemetery<br />

6

Inside the new visitors‟ centre, the floor to ceiling windows look out over Ayrshire<br />

cows knee deep in grass, and further away, a field of maize, and yew, willow and poplar<br />

trees. An interminable soundtrack accompanies our visit. A young English woman‟s voice<br />

recites a list of soldiers‟ names as each one‟s photograph flashes up on a small screen. As<br />

well as a display of twisted and rusted metal shell cases, cans, shovels and water bottles, there<br />

are soldiers‟ personal things such as <strong>photos</strong>, letters, medals, and a pay book; also chilling<br />

official letters informing the family of the death of a soldier. It‟s a particularly heartrending<br />

reminder of the loss of each single life.<br />

An even grimmer place is the Langemark cemetery where 44,000 German soldiers<br />

were buried, 25,000 in a common grave, and many unknown. Oak trees overshadow the<br />

graves and the only light point is a beautiful life <strong>size</strong> sculpture in bronze by Emil Krieger, of<br />

four mourning soldiers. Some school pupils from Horley in Surrey have placed a wreath <strong>with</strong><br />

a quotation from Einstein: “I know not <strong>with</strong> what weapons WW3 will be fought. WW4 will be<br />

fought <strong>with</strong> sticks and stones”.<br />

At every crossroads there are road signs pointing to Commonwealth War Graves<br />

Commission cemeteries. If that isn‟t enough of a reminder to the local farmers, the two<br />

hundred tons of WW1 ammunition (twenty tons of it filled <strong>with</strong> chemicals) thrown up by<br />

ploughs and other implements each year surely is. They leave it by the roadside to be<br />

collected by bomb disposal experts. Apparently avid private collectors are occasionally<br />

killed trying to dismantle bombs illegally. We visit memorials to New Zealand soldiers at<br />

Gravenstafel and Messines, remembering our visit to the one in Longueval in France two<br />

years earlier when we bandicooted potatoes from a farmer‟s field <strong>with</strong> our army surplus<br />

shovel.<br />

It‟s been a melancholy couple of days but it feels right to come here and pay our<br />

respects. Flanders these days is a thriving and peaceful place. The local Oud Bruin beer goes<br />

down a treat at the end of long hot days, and the bread and tomatoes are out of this world. I<br />

luxuriate in the old cotton duvet cover and pillowslips we brought from home, and John is<br />

thrilled <strong>with</strong> the little shortwave radio. I‟m reading “Great Expectations”, and, best of all,<br />

we‟re completely anonymous.<br />

We head to the coast, just a few miles from the border <strong>with</strong> the Netherlands, and<br />

spend a peaceful night in Knokke Heist, a popular seaside town <strong>full</strong> of well dressed and<br />

orderly folk. Beach huts, kites, buckets and spades, and all the paraphernalia of the European<br />

beach experience are laid out along the shore. An array of pedal powered contraptions is<br />

available for hire and people pedal around <strong>with</strong> whole families on board. We take advantage<br />

of the densely packed apartment blocks on the sea front, pull out the laptop and easily get<br />

online.<br />

The seven weeks we spent in the van in Italy and France two years ago were a great<br />

rehearsal for this trip in every way and John has easily slotted back into driving on the right<br />

7

hand side of the road. French drivers are impeccable: attentive to the rules and hugely<br />

courteous, while the Italians take a more edgy and intuitive approach. But, the driving habits<br />

of different countries aside, there‟s always an extra level of complexity involved in driving a<br />

UK vehicle over here as we‟re at a distinct disadvantage <strong>with</strong> the steering wheel on the right.<br />

John has to remember to keep his right shoulder to the kerb when setting out on an empty<br />

road, a risky moment when it‟s easy to revert to old habits. And I have to look out the<br />

passenger‟s window whenever we overtake or change lanes. Long days of driving can be<br />

exhausting.<br />

Gaasperplaas<br />

Our next night is at Zoutelande across the water in the Netherlands where the beach is<br />

vast at low tide and there are stone defences to deflect the waves. Way off to the west is the<br />

port of Zeebrugge <strong>with</strong> massive cranes and wind turbines. We pass a Dow chemical factory,<br />

then plunge into a long undersea tunnel to enter the Delta.<br />

The Rhine Delta consists of islands and peninsulas that make up the province of<br />

Zeeland. It was a lonely and isolated place until tunnels and bridges were constructed there.<br />

High sand dunes keep the North Sea at bay and we park in a sheltered car park in the sun.<br />

The local beach goers have popped their children and dogs into carriers on their bikes and<br />

ridden home. John cooks up a curry in the back and I open the laptop <strong>with</strong> a glass of wine in<br />

the front seat. We tune in to the BBC World Service. There are a few other camper vans:<br />

German, Dutch and French. Next morning we have a cold wash and shampoo in the hand<br />

basin in the public toilet. Luxury.<br />

As we set out towards the storm surge barrier which was constructed to prevent<br />

floods, and the artificial island Neeltje Jans, people are out biking past fields bordered <strong>with</strong><br />

wide areas of wildflowers and sunflowers. We stop for coffee <strong>with</strong> toast and Marmite and<br />

watch a family training some border collies to herd sheep. Then we drive onto the<br />

breakwater which is two miles long, <strong>with</strong> Neeltje Jans in the middle. It‟s a theme park <strong>with</strong> a<br />

fantastic museum explaining the history of the area, a whale information section, plus an<br />

aquarium, performing seals, lots of information on wildlife, play areas, and no signs telling<br />

you what to do.<br />

A disastrous flood here in 1953 killed 2,000 people and caused 75,000 to be<br />

evacuated. The defences against the sea had been allowed to run down in the post war<br />

recovery and the Cold War, so they were unprepared for the flood. The protection scheme<br />

took several decades to complete, <strong>with</strong> state of the art engineering, and environmentalists<br />

ensured that it incorporated features to protect the marine and bird life. Today, beautiful<br />

families are exploring the sights, the little girls dressed in stylish but pleasingly childish<br />

clothes.<br />

8

We exit the storm surge barrier, cross the rest of the Delta and then skirt Rotterdam on<br />

huge motorways <strong>with</strong> frightening cloverleaves. Immense port and industrial areas stretch<br />

into the distance. It‟s a relief to arrive at Delft and find a spot for the night in a car park<br />

beside a shopping centre. It‟s the most beautiful little town, all canals and quaint old<br />

buildings. Unfortunately even though this is where Vermeer lived and worked (and where<br />

the novel and film “The Girl With The Pearl Earring” are set), there are no original Vermeer<br />

paintings held here. We visit the Oude Kerk where he is buried. Again it‟s all bicycles, <strong>with</strong><br />

children carried in unorthodox ways including babies in front packs. The cyclists are so<br />

relaxed, texting and eating, <strong>with</strong> not a helmet to be seen. The canals have cute little bridges<br />

over them and abundant moorhens <strong>with</strong> chicks, plus we see a duck nesting box which<br />

consists of a woven wicker house <strong>with</strong> a ramp. When I buy a couple of pieces of battered<br />

fish for lunch, I ask what sort of fish it is. In perfect English, as always, the guy says “Hake,<br />

a cousin of the haddock”. The Dutch will be the most perfect English speakers we come<br />

across on our trip.<br />

Trying to leave town we get tied up in canals and one way streets and stop to ask a<br />

young man for directions. He tells us about his trip to New Zealand when he went bungy<br />

jumping, skydiving and swimming <strong>with</strong> dolphins. We see birds flying high and decide that<br />

they must be storks.<br />

Next stop is Aalsmeer a small peaceful town of canals, and a lake where people are<br />

out boating in a variety of craft. We park by the lake, cook and eat dinner outside, boil the<br />

Kelly kettle (thermette) for the dishes, and spend a pleasant evening <strong>with</strong> the moorhens,<br />

swans, ducks, geese, thrushes, pigeons, crows and magpies. But as often happens when we<br />

park on the edge of a town, there are a few too many people coming and going in the night,<br />

so about midnight we drive into town and find a spot in a car park.<br />

Next day it‟s my birthday and we‟re up at 6.30, driving back to our spot by the lake<br />

for a lovely breakfast outside. Then in a state of great excitement we head to the<br />

Bloemenveiling flower auction, the largest in the world, covering 600,000 square metres or<br />

one hundred and forty five football fields. Twenty one million flowers are auctioned there<br />

every day, <strong>with</strong> a daily turnover of six million Euros, and nearly two thousand people are<br />

employed. It‟s a cooperative of six thousand growers from Europe, Africa, South America<br />

and the Middle East. The price starts high and comes down: a Dutch auction. The flowers<br />

are delivered at night, auctioned during the morning, then shipped out. We stroll along<br />

elevated walkways above the action and beneath us is a frenetic scene of people <strong>with</strong><br />

barrows, trolleys and bikes, and trains <strong>with</strong> carriages laden <strong>with</strong> flowers, all busily moving<br />

the most glorious blooms here and there <strong>with</strong> little fuss and lots of good humour. We look in<br />

at the auction rooms where the buyers sit in a tiered theatre at computer terminals, <strong>with</strong> the<br />

flowers at the front, and computer displays track the sales. Quality is everything and the<br />

flowers are examined in a testing area <strong>with</strong> the title of “fleur primeur” awarded to a select<br />

few. The most popular varieties are roses, then tulips, chrysanthemums and gerberas. From<br />

9

above it seems like a glorious ballet, or a metaphor for the Netherlands and their ability to<br />

organise things <strong>with</strong> such efficiency and flair, while appearing casual and relaxed.<br />

Bloemenveiling Flower Auction<br />

Afterwards we take the motorway to Amsterdam in a thunderstorm. The morning is<br />

dark <strong>with</strong> rain and we manage to take a couple of wrong turns. After a quick recovery we<br />

find the Gaasperplaas camping ground on the outskirts of the city, and wait in the queue<br />

outside the gate. They put us in an area <strong>with</strong> the other camper vans then we go to the camp<br />

cafe for a coffee. The mostly male young customers in the cafe seem sullen and rude, and the<br />

woman behind the counter is tough and stressed. Then there‟s an altercation at the next table.<br />

A young man is rolling a joint, the manager appears and has him out the door so fast his feet<br />

barely skim the ground. He is read the riot act then one of his friends, very Bob Marley in<br />

appearance, joins in the argument, and starts accusing the manager of being a racist. We‟re<br />

shocked. They leave shortly afterwards and we chat to the manager who tells us that it‟s<br />

illegal to smoke cannabis in the bar. He‟s not concerned about what they might do on their<br />

camp site, but <strong>with</strong> children around, any public smoking of drugs is forbidden. We get the<br />

impression that the cannabis laws mainly suit the tourists, and that the locals are unhappy<br />

about what goes on.<br />

By the time we get settled it‟s midday and bleary eyed and sullen young men are<br />

lurking everywhere. Most emerge from tents in a field, and <strong>with</strong> the rain we feel like we‟re<br />

in a Woodstock time warp. The car park is <strong>full</strong> of cars from all over the EU. One is called<br />

Babylon Van. We suddenly feel very old and bored <strong>with</strong> it all, but the meaning of<br />

Gaasperplass is clear.<br />

10

In the camper van area the Italians never stop talking. Some are very jolly but there<br />

are a couple of peevish women who lock themselves in their campers, leaving the husbands<br />

to circle pathetically and knock on the doors and windows. It‟s very entertaining.<br />

The Potato Eaters<br />

We catch the train from the camp into Amsterdam, and the centre of town is a bit of a<br />

disappointment <strong>with</strong> crowds of young men on stag dos, endless cannabis cafes, and party pill<br />

and porn shops. We console ourselves <strong>with</strong> Irish stew in an Irish pub and watch some of the<br />

Chinese Olympics Opening Ceremony. Needing inspiration, we decide to spend the next day<br />

at a museum.<br />

The van Gogh Museum is a great choice, a wonderful antidote to the hedonistic<br />

tourism we‟ve seen so far. “The Potato Eaters”, which shows the dark interior of a house and<br />

peasants eating a meal of potatoes, and “Almond Blossom” (white blossom against a bright<br />

blue sky) are highlights.<br />

We go for a long walk through streets of apartment blocks designed in the style of the<br />

Amsterdam School of architecture. This is Old Dutch combined <strong>with</strong> Art Nouveau, from the<br />

years 1910 to 1930. The apartments were built for working class people and they look as<br />

good to live in now as they were then, all curving lines <strong>with</strong> lots of detail, none higher than<br />

four stories. We walk along canals lined <strong>with</strong> boats. Surprisingly a number are sunken and<br />

semi submerged.<br />

Next day we go into town again and have a look at a group of beautiful old two<br />

storied houses built side by side in the 19 th century, each in the style of a different country:<br />

Germany, Spain, Italy, Russia, Netherlands, France and England. It‟s such an orderly and<br />

civilised city in so many ways. Then we stumble upon the Hollandse Manege, an indoor<br />

riding school built in 1882 and run today <strong>with</strong> fifty horses. From the street we can see ponies<br />

in beautiful old stalls remarkably similar to the illustrations in my childhood copy of “Black<br />

Beauty”. Inside, from a viewing platform on a mezzanine floor we watch a class of eight<br />

adult beginners walking for fifteen, then trotting for thirty minutes. I find it fascinating.<br />

As a pedestrian in Amsterdam it‟s a challenge to stay alert for the cycles, scooters,<br />

trams, buses and cars whizzing past. Children are carried in every way imaginable on cycles,<br />

including standing up on the back. We go to Vondelpark, a big inner city park <strong>full</strong> of people<br />

enjoying themselves, and come across a stage <strong>with</strong> musicians performing. The audience<br />

contains all ages including tiny children climbing onto the stage and homeless men grooving<br />

up the front. It‟s a very tolerant and relaxed group of people. Afterwards we walk to the<br />

Riaz restaurant for delicious Surinam curries <strong>with</strong> roti.<br />

11

Seeing wonderful sights day after day can get exhausting so we spend the next day in<br />

the camp reading travel guides, looking at maps, and grappling <strong>with</strong> the washing machine and<br />

drier.<br />

We‟ve been on the road less than two weeks and still have a lot to learn. In hindsight<br />

we should never have wasted money on a camp in Amsterdam. In all the big cities we visit<br />

after this we go it alone in car parks or parked on the street. At this early stage we‟re still<br />

hung up on showers and laundries.<br />

Next day we queue in the rain outside Anne Frank‟s house for an hour <strong>with</strong> people<br />

from all over the world, mainly teenagers. It‟s the building where her father had his business<br />

and where the family and some friends were hidden for two years in an annex at the back.<br />

When they were betrayed and taken to concentration camps, all the furniture was stripped<br />

from the rooms. It hasn‟t been replaced but the rooms now contain <strong>photos</strong>, writings, and film<br />

of Anne‟s father Otto Frank, and the women who worked <strong>with</strong> him, talking about what<br />

happened. There are detailed models of the rooms showing the layout. Even the pencil<br />

marks on the wallpaper showing the children‟s heights are still there. The concealed entrance<br />

to the annexe is shown <strong>with</strong> a bookcase jutting out from the wall. We find it all quite<br />

overwhelming. I hear a young American woman say “The diaries are really good. It‟s kind<br />

of like an early Big Brother”.<br />

We take a walk past some of the places of significance to the Dutch Resistance.<br />

Jewish people hid in animal enclosures in the zoo to keep safe, and some non Jews chose to<br />

wear yellow stars in solidarity <strong>with</strong> their Jewish friends. Apparently the Nazis confiscated<br />

people‟s bikes, and years later, in the 1960s, one of the Dutch princesses married a German.<br />

As they paraded down the street people called out “Give me back my bike!”<br />

Leaving Amsterdam we decide to take the slow route to Arnhem and drive the back<br />

roads past Hilversum, Amersfoort and Scherpenzeel, getting lost at times but enjoying the<br />

houses <strong>with</strong> their thatched roofs, canals and countryside. Horses and small dairy herds stand<br />

in lush pasture. Massive silage heaps sit close to houses. The Brits and Europeans seem to<br />

have a higher tolerance for muck heaps and silage than Kiwis do.<br />

We drive through fabulous areas of beech forest and miles of tree-lined avenues <strong>with</strong><br />

cycle paths beside the road. We want to see the Rhine so we stop at Oosterbeek, now a very<br />

wealthy little town, where the Battle of Arnhem was fought in WW2. We talk to a guy <strong>with</strong> a<br />

very old camper, and he tells us that taxes are very high, people have to work hard to make<br />

any money, everyone is watching you, and a disabled person only gets 430 Euros a month to<br />

live on. He also says that we shouldn‟t attempt to sleep the night in the car park as the Politie<br />

will come and move us on. We ignore his advice and stay the night parked opposite a hotel<br />

where casualties were treated during Operation Market Garden in September 1944, when the<br />

Allies launched the largest airborne operation of all time aiming to secure bridges in German<br />

12

occupied areas. Mindful however of the possible interest of the Politie, I cook a discreet meal<br />

of curried kidney beans, instant mash and green beans <strong>with</strong> the windows and door closed.<br />

A Bridge Too Far<br />

Next morning we drive down to the wide Neder Rijn, a branch of the Rhine, to have a<br />

coffee, and watch the little ferry taking people and bicycles across. The river is very busy<br />

<strong>with</strong> big barges and all sorts of pleasure boats passing.<br />

We visit the Airborne Museum which has a memorial <strong>with</strong> the following heart<br />

stopping inscription: “To the people of Gelderland 1944. 50 years ago British and Polish<br />

airborne soldiers fought here against the odds to open the way into Germany and bring the<br />

war to an early end. Instead we brought death and destruction for which you have never<br />

blamed us. This stone marks our admiration for your great courage, remembering especially<br />

the women who tended our wounded. In the long winter that followed your families risked<br />

death by hiding Allied soldiers and airmen while members of the Resistance helped many to<br />

safety. You took us into your homes as fugitives and friends, we took you forever into our<br />

hearts. This strong bond will continue long after we are all gone.”<br />

The museum tells the story of the ill fated Operation Market Garden, where Polish,<br />

American and British troops parachuted and glided in, in an attempt to capture bridges on the<br />

Rhine and other waterways. At the same time British ground troops advanced from the<br />

Belgian/Dutch border. Once the Rhine was crossed, the intention was to surround the Ruhr<br />

and advance on Berlin. The operation was unsuccessful, leaving 17,000 dead from the<br />

Airborne Corps, and 10,000 from the ground forces. The bond forged between the Allies and<br />

the local people is legendary. For me the most poignant items in the museum are old<br />

ampoules of morphine and tablets of Benzedrine in a first aid kit.<br />

We walk through the forest surrounding the museum and hear the ricocheting bullet<br />

call of nuthatches as they walk head first down tree trunks looking for insects. Then bizarrely<br />

twenty soldiers <strong>with</strong> weapons march along the road.<br />

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery in Oosterbeek has the graves<br />

of 1750 soldiers, including two New Zealanders. It‟s surrounded by beautiful old oak trees.<br />

Feeling devastated by the particularly savage history of this area, we retire to the river bank<br />

to boil the Kelly kettle, have a cup of tea, cook sausages over the embers, and eat them <strong>with</strong><br />

instant mash, green beans and left over curry sauce. A few men are fishing further along the<br />

river. We decide to investigate a bridge in the distance and end up on a motorway driving<br />

across the main branch of the Rhine on what turns out to be a massive new suspension bridge.<br />

Mesmerised by it all we miss the exit and continue to Nijmegen past a sprawling industrial<br />

area and canals. It‟s been raining, and the black sky contrasts beauti<strong>full</strong>y <strong>with</strong> the intense<br />

green of the vegetation.<br />

13

The last bit of sightseeing we have time for in the Netherlands is the Hoge Veluwe<br />

National Park. On the drive there John comments that the roads here are so smooth that he<br />

can drink a mug of apple juice while driving and not spill a drop. In three months time we<br />

will experience the complete opposite in Romania, where it can be smoother to travel off the<br />

road.<br />

The Hogue Veluwe National Park covers an area of twenty one square miles, made up<br />

of heathlands, sand dunes and woodlands. A wealthy couple, Anton Kroller and Helene<br />

Kroller-Muller, developed the land and acquired an important art collection here in the early<br />

20 th century. It was subsequently taken over by a trust. It‟s a wonderful place to visit, <strong>with</strong><br />

paths and roads throughout, and beech, Scots pine, and silver birch forest. Because of over<br />

farming in previous centuries there are also large areas of sand.<br />

The art museum has floor to ceiling windows which look out onto the forest. It‟s a<br />

fabulous setting to appreciate paintings by van Gogh, Picasso, Monet and Mondrian. Also<br />

sculptures by Rodin, Dubuffet, New Zealander Chris Booth and others are displayed on<br />

undulating land among fabulous trees and lawns.<br />

We end our visit by cooking dinner on the heath, then spend the night in nearby<br />

Otterlo, at the side of the road between a cemetery and a field of maize. It‟s a peaceful rural<br />

scene <strong>with</strong> just a few mildly curious people walking their dogs past us the next morning.<br />

Heading to the German border via Appeldoorn and Almelo we realise that we‟ve<br />

forgotten to take the classic photo of a cow by a canal! And we‟ve bypassed the town of<br />

Rectum, a lost photo opportunity.<br />

14

Chapter 2 Germany<br />

16 August – 3 September<br />

Vitriolic<br />

We cross into Germany on a scorching hot day and the only difference is the dairy<br />

cows are replaced by cereal crops and potatoes. At the town of Lingen we buy a dictionary,<br />

and stay the night, slightly tense to be in a new country, letting the language wash over us.<br />

Next day the landscape is <strong>full</strong> of oak and beech forest, factory farms <strong>with</strong> vast fields<br />

and few fences, wind generators, massive brick barns <strong>with</strong> solar panels, and horses. The<br />

roads are beautiful and empty. We‟re looking for a pool and a shower and end up at Bad<br />

Fallingbostel, in the Netto supermarket car park for the night, eating a tired travellers‟ dinner<br />

of baked beans on instant mash followed by custard and banana.<br />

The pool has a curious sign outside: “Groups of British children <strong>with</strong>out an adult will<br />

not be allowed to enter the premises”. John is initiated into what will become a familiar<br />

activity – exchanging morning greetings <strong>with</strong> the other nude blokes in the communal shower.<br />

I‟m pathetically grateful to find a private cubicle in the women‟s area.<br />

What‟s brought us to this part of the country is the Vogelpark (bird park) at Walsrode,<br />

and by the time we arrive it‟s busy <strong>with</strong> bird lovers in spite of the rain. It‟s a huge botanic<br />

garden of beautiful trees and plants in immaculate order, <strong>with</strong> enclosures for the birds, and<br />

mature conifers, rhododendrons and roses attractively laid out and well tended. As we enter<br />

the humid rainforest enclosure we discover a demister for spectacles. That German attention<br />

to detail! The penguins are very popular, being so far from home, but we love the exotic<br />

roadrunners, toucans, hornbills, shoebills, hyacinth macaw, flamingos, scarlet ibis and blue<br />

crowned pigeon.<br />

We decide to take the fast autobahn south to Goslar, through a picturesque rolling<br />

landscape of forests and farms <strong>with</strong> crops. The motorways have frequent picnic areas <strong>with</strong><br />

toilets and parking, as well as commercial rest areas <strong>with</strong> cafes. The van‟s cigarette lighter<br />

dies, a catastrophe as we use it to charge everything, but fortunately John has the correct fuse<br />

on board and manages to fix it.<br />

In Goslar we walk through the rain to the main square which is made up of perfect old<br />

timber framed buildings restored to the nth degree. Many are decorated <strong>with</strong> bricks,<br />

<strong>colour</strong>ful carvings, friezes, and writing in golden script. The town boasts eighteen hundred<br />

buildings in this style, <strong>with</strong> the old part now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Goslar, part of<br />

the Hanseatic League, was founded in the 10 th century after silver was discovered in the<br />

nearby Rammelsberg mountain.<br />

15

The Rammelsberg Mine was worked continuously for over a thousand years then<br />

closed in 1988 when the reserves of silver, lead, zinc and copper were exhausted.<br />

Archaeological evidence shows that there was mining on the site as far back as three<br />

thousand years ago. We visit the old mine and museum, and take the underground tour <strong>with</strong><br />

a female guide who gives us great explanations in English, after she‟s given the spiel in<br />

German.<br />

The ore all came from the same rock, and <strong>colour</strong>ful vitriol, which was formed by<br />

water dripping over elements like copper and zinc, was used for medicines. In the Middle<br />

Ages the miners descended eighteen hundred feet into the mine on narrow metal ladders<br />

carrying fifty five pounds of gear. It took them an hour to get down and probably longer to<br />

ascend. They worked for part of the year, and were paid only for what they extracted. Prior<br />

to the 1800s when explosives were introduced, big fires would be lit in the mine on a Sunday,<br />

causing the rock to explode, then in the following days the miners would enter and extract the<br />

ore while the temperature was still high. Because the rock was incredibly stable, formed by a<br />

long extinct volcano, there was no need for props and never any cave ins. Waterwheels were<br />

also introduced in the 1800s, and this enabled the miners to work all year and increase their<br />

income. We see the old water channel and two waterwheels (thirty feet in diameter), one to<br />

take water in, the other to take the ore out. We learn that tin was brought over from Cornwall<br />

to make bronze.<br />

The museum has extensive displays of old mining equipment plus photographs and<br />

explanations of the mining process. For us the most fascinating part is the information on the<br />

miners in the 20 th century. During WW2 people were brought in from France, the<br />

Netherlands, Belgium and the Ukraine (many young women) as forced labour, and Italian<br />

officers and soldiers were sent there after the fall of Mussolini. There is film footage of Nazi<br />

meetings in Goslar, and a folder of pages of documentation for a Ukrainian man taken there<br />

as forced labour. The words of a song sung by Ukrainian forced labourers (to the tune of a<br />

popular Russian folk song) say it all:<br />

“Fate has cast so many to this place, There is no way back home, The road towards<br />

the East is closed, Thus dwindle the years of our youth.<br />

Every morning I get up, Half starved and very homesick, The Germans have made me<br />

a slave, I view them <strong>with</strong> anger and wrath in my heart.<br />

Sirens are wailing, it is midnight, Our nerves are on edge, The English Air Force<br />

sends in squadrons, To make life difficult for the Germans.<br />

Over there where the east is ablaze, There the long way leads back home to mothers<br />

and brothers, They struggle hard for their freedom, While here we slave for the hated<br />

people.”<br />

16

From the 1960s men from Spain worked in the mine, and Turks from 1971.<br />

Sometimes old or injured miners would make a model of the workings of the mine which<br />

would be displayed at fairs and gatherings. We see a perfectly crafted one from 1904 <strong>with</strong><br />

tiny figures performing tasks on several levels. There is also a miners‟ banner from 1787,<br />

and pages from a book on mining called “De Re Metallica” (“On the Nature of Metals”)<br />

published in 1556.<br />

That evening we have a drink in the square and watch the world go by. We take our<br />

washing to the laundrette where they offer to put it in the drier for us so it will be ready to<br />

collect in the morning. We spend a peaceful night in the car park <strong>with</strong> a few other camper<br />

vans and next morning visit another excellent pool for a shower.<br />

As we head towards Quedlinburg we see that the leaves on the chestnuts are turning<br />

yellow. Swifts are performing their crazy airborne antics. Haybales crouch like wildebeest<br />

in a huge field while buzzards circle above.<br />

Quedlinburg is a little town <strong>with</strong> cute old timber framed houses, many of them<br />

rundown, similar to Goslar but visibly lacking the UNESCO funding. It has the oldest timber<br />

framed house in Germany, built about 1300, now a museum. The local children are having a<br />

flea market in the village square <strong>with</strong> books and toys spread out in front of them on the<br />

cobblestones: dolls and plastic castles alongside action figures. Colourful geraniums in<br />

baskets adorn many of the buildings. John buys me an antique ring made of seventeen little<br />

Czech garnets (Granat in German) set in silver.<br />

Two Beavers and a Weasel<br />

We work out the route to our friend Rieke‟s address on the outskirts of Halle by<br />

looking up Google maps and Mappy. In the back of the van we‟ve brought a carton of her<br />

gear from when we lived and worked together in Surrey. We‟re looking forward to staying<br />

<strong>with</strong> her family for a few days, after meeting them when they came to visit in England a few<br />

months ago. We travel on empty motorways past endless wind turbines.<br />

It‟s wonderful to find their place at last and a big thrill to see friends after two weeks<br />

on the road. On the first night we eat a delicious traditional German dinner of<br />

Schweinebraten (pork) <strong>with</strong> Klosen (dumplings), sauerkraut and potatoes, and for dessert<br />

Rote Grutze (made by gently cooking mixed red berries like red currants, raspberries and<br />

cherries, adding fruit syrup and sugar, then thickening the mixture <strong>with</strong> cornstarch, before<br />

setting it in the fridge).<br />

We go for a walk around the neighbourhood, past fabulous vegetable and flower<br />

gardens. A former electricity substation, a tall narrow brick building, has been converted into<br />

a bird house where the birds can feed and collect nesting material.<br />

17

Rieke‟s mother produces wonderful German breakfasts for us each day <strong>with</strong> beautiful<br />

bread rolls, various sausages and salamis, fishy things, jams, tea, coffee and other drinks. On<br />

this day we really need it as we‟re heading off on a canoe trip on the Saale/Unstrut River<br />

through an area famous for its wine.<br />

We enter the river in our open Canadian style canoes at Grossheringen, and<br />

immediately relax as we glide past willows at the water‟s edge, and oak forests and vineyards<br />

on steep hillsides. It‟s a wide slow flowing river <strong>with</strong> swallows, nuthatches, ducks, herons,<br />

and pigeons. A couple of nutria, little beaver like creatures <strong>with</strong> thin tails, pop their heads out<br />

of the water, and we see a black weasel. There are old stone bridges, and a big gorge <strong>with</strong> a<br />

couple of castles. We stop for a traditional German lunch at Bad Kosen: bratwurst <strong>with</strong><br />

mustard, potato, sauerkraut, and salad. We portage the canoes at this point because there‟s a<br />

low dam which used to run a water wheel. For a couple of centuries it powered pumps to<br />

take salty water from a spring, six hundred feet uphill, to a huge wooden post and beam<br />

structure (the graduation) about five hundred feet long and thirty feet high, filled <strong>with</strong><br />

bundles of sticks, which propelled the water into the air in a fine concentrated spray. People<br />

used to go there to breathe it to improve their health. The engineering is quite incredible.<br />

Two parallel pistons slowly jerk back and forth providing power to the pump while the water<br />

is carried in a trough between them. It still functions perfectly.<br />

After a relaxing day on the river we eat a delicious dinner in the garden: bread,<br />

sausage, tomatoes, gherkins, sardines, horseradish, liverwurst, and white wines from the area<br />

we canoed through. As we sit under an old willow we look up and see two owls looking<br />

down at us. They‟ve been nesting here for two years now. At nine o‟clock one of them<br />

soundlessly flies away. I think they‟re tawny owls.<br />

Next day we visit Halle <strong>with</strong> Rieke‟s father as our guide, and Rieke the ever patient<br />

interpreter. We walk around the old cemetery which fell into disrepair in the days of the<br />

GDR (Communism), but is now being restored <strong>with</strong> money from an American woman, the<br />

daughter of a Nobel Prize winning scientist born in Halle. We go past the house where<br />

Handel was born and into an old church where we see the death mask of Martin Luther,<br />

whose funeral procession passed through the town. Halle‟s wealth was founded on salt<br />

which was produced here for centuries, and later it was the centre of the chemical industry.<br />

We see a sculpture of a religious figure grappling <strong>with</strong> another person. Because it was<br />

created in the GDR days, the religious figure couldn‟t be shown <strong>with</strong> his high hat and was<br />

given a bouffant hairdo instead. We also see a house where a senior Catholic cleric lived<br />

<strong>with</strong> his girlfriends. A modern mural shows various figures including the girlfriends, and a<br />

rascal who was put to death after seducing one of them.<br />

We lunch on Kartoffelpuffer mit Apfelmus (potato fritters <strong>with</strong> applesauce) then head<br />

home for coffee and cake in the garden <strong>with</strong> all the family. We cook three curries for dinner<br />

and they go down very well <strong>with</strong> everyone. It‟s fun using our few words of German,<br />

especially <strong>with</strong> the wee four year old, but mainly Rieke interprets for us all. It‟s our last night<br />

18

and we ask so many questions about the GDR days and German history. When we fall into<br />

bed and John tries unsuccess<strong>full</strong>y to tune in to the BBC, the only station he can get is Radio<br />

Russia <strong>with</strong> news about their actions in Georgia and how many medals they won at the<br />

Olympics.<br />

The Gingham Glider<br />

Sadly we leave Halle and head south east towards Dresden on the motorway, stopping<br />

at a rest area <strong>with</strong> lorries from Slovakia, Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary and the<br />

Netherlands. At Grimma we visit a supermarket to buy fish fingers which we eat for lunch<br />

on heavy bread <strong>with</strong> mayonnaise and sauerkraut, washed down <strong>with</strong> a deliciously syrupy malt<br />

drink. We stop in the village of Colditz, tidy things in the back of the van, and look out the<br />

window to see a Ford Escort <strong>with</strong> GB on the back parked nearby. We don‟t see the owners<br />

but it‟s always a slight thrill to see another Brit vehicle, not at all surprising in such close<br />

proximity to Colditz Castle, the infamous WW2 prisoner of war camp for Allied officers <strong>with</strong><br />

a history of escaping.<br />

We walk up to the castle not knowing what to expect and discover that there‟s a tour<br />

in English about to start. Apparently they have twenty thousand visitors a year from all over<br />

the world, including many Brits who are mainly interested in the escape attempts. In our tour<br />

there are two young Brit guys and a Danish/Spanish couple. The castle dates from the 16th<br />

century and had been used as a workhouse for the poor, then from the early 1800s as a mental<br />

hospital. Now it‟s part museum, part youth hostel, and a large area is being restored for a<br />

music centre. It‟s situated on a hill above the town, <strong>with</strong> a high terrace overlooking the river<br />

and surrounding countryside. One former Olympic medal winning prisoner managed to<br />

escape off the terrace by miraculously climbing down the outside of the windows, only to be<br />

caught in the garden.<br />

The tour guide mentions the Geneva Convention frequently, making the place sound a<br />

bit like “Hi de Hi”. Most of the successful escape attempts were from the park or the kitchen<br />

and it seems that the tunnelling may have been good for morale but not much else. The<br />

French made a painstaking and ingenious attempt where seventy would have escaped through<br />

a tunnel if they hadn‟t been discovered. A special section housed the relatives of high profile<br />

Brits who were watched extra closely. They included two Churchills and the son of WW1<br />

commander Field Marshall Haig.<br />

The most intriguing object on display is a replica of a glider (the Colditz Cock) that<br />

the Brit prisoners made in secret at the top of the castle. They never got a chance to use it but<br />

it was photographed by the Americans when they arrived to liberate the camp, and<br />

subsequently destroyed. It‟s one third the <strong>size</strong> of the original glider, made of recycled<br />

materials, and covered in blue gingham from bedding, giving it the rounded form of a soft<br />

toy.<br />

19

Gingham Glider<br />

The stories from Colditz are fascinating. One prisoner used to reproduce maps by<br />

making up a jelly from a food parcel, forming a large rubbery stamp, then using it to print<br />

thirty copies. Someone else sent a letter home to his father asking him to go to the British<br />

Museum to see if he could find the plans to Colditz Castle, then send them over, which he<br />

did. There‟s a chapel <strong>with</strong> galleries on three levels where the inmates of the workhouse were<br />

sent to church <strong>with</strong> a memorial to the workers in the mental hospital who died in WW1.<br />

The Allied prisoners made two dummies which they used to take outside for the roll<br />

call when anyone escaped, to trick the guards into believing that everyone was present. Two<br />

replica dummies now stand in the yard, one bearing a remarkable resemblance to Rowan<br />

Atkinson. The tour and the museum are presented in a “Boys‟ Own Annual” style which is<br />

probably what the punters want.<br />

Back in the van we have black bean stir fried vegetables <strong>with</strong> sauerkraut and watch<br />

the boy racers revving it up along the main street in their flash cars. John says he‟s noticed<br />

we‟re the only ones who leak oil in car parks.<br />

The Freital Position<br />

Next day, back on the motorway heading to Dresden, we drive past ploughed fields<br />

and wind turbines, and see a kestrel, buzzards, and flocks of starlings. An old red Skoda <strong>with</strong><br />

the top down and three men huddled inside overtakes then leaves us for dead. We search for<br />

a place to park on the edge of Dresden, preferably a car park beside a railway station. We<br />

end up driving down a narrow valley and check out Tharandt, a little village of cute old<br />

20

uildings, like a mountain resort, <strong>with</strong> steep forest on both sides. We decide it‟s not ideal and<br />

drive on to Freital, a bigger town and find a park by the railway station and bus terminal <strong>with</strong><br />

a toilet, internet cafe, and lots of sun and space. It‟s one of our best parks.<br />

Walking along the main street Dresdenstrasse for the length of the town, we see many<br />

abandoned factories and newish apartment blocks. The visitors‟ centre has information in<br />

English and we discover that Freital is a former coal mining town, and the main industry is<br />

now a steelworks. The museum is a small castle, the home of the former coal mine owner,<br />

which reminds us of the Welsh valleys and Merthyr Tydfall. We swoon over the old enamel<br />

and cast iron cookware, and enamel street signs and house numbers in a second hand shop.<br />

John buys an enamel number one, white on a blue background and I find an old enamel onion<br />

container <strong>with</strong> “Zwiebeln” written on it in German script. There are also army hats<br />

emblazoned <strong>with</strong> the hammer and sickle. When we tell the charming woman behind the<br />

counter that we‟re from New Zealand, she becomes quite animated and shows her boss where<br />

it is on an old globe.<br />

In the evening we walk past the steelworks lit up for the night shift. It‟s near a street<br />

of stylish four storeyed houses from the early 1900s, some run down and others in perfect<br />

condition <strong>with</strong> lovely gardens and huge trees. Back home, over a year later, I discover that<br />

Allied prisoners of war in Freital witnessed Allied bombing raids on factories there. Between<br />

1946 and 1990 a company called Wismut mined uranium near Freital, extracting four<br />

thousand tons, and many miners died of lung cancer.<br />

Next day we drive to a pool up the valley for a shower, and discover a peaceful car<br />

park beside allotments where people have their summer houses, <strong>with</strong> <strong>colour</strong>ful gardens <strong>full</strong> of<br />

roses and sunflowers, and happy people out in the sun tending them and talking. We have<br />

toast and Marmite <strong>with</strong> coffee and read in the back of the van in the sun. I realise that I‟m<br />

reading a copy of the Sunday Times which is a month old. We hear Crowded House and<br />

Johnny Farnham on the local radio station. One night we pick up a Polish station and hear<br />

about David Beckham and a double decker bus. We wonder if it‟s the closing ceremony of<br />

the Olympic Games in Beijing.<br />

Public sculpture is abundant in the former East Germany, and Freital has the most<br />

joyous examples: a square pool <strong>with</strong> just the partial heads and shoulders of happy people<br />

poking out, a topless woman wearing a serious expression washing a man‟s hair over a large<br />

bowl, and some dwarves drinking and dancing while a fiddler plays.<br />

21

Sculpture, Freital<br />

We‟re astounded to see alcohol on sale at petrol stations, cheap cigarettes in vending<br />

machines on street corners, and huge advertising billboards showing young people having a<br />

great time while smoking. When we asked Rieke about whether the government intervened<br />

in public health matters here, she said that post GDR, everyone was understandably very keen<br />

to avoid anything resembling a nanny state.<br />

At the local petrol station I have a lovely exchange <strong>with</strong> the woman attendant who<br />

speaks no English but manages to tell me that her son is on a cycle trip from one end of New<br />

Zealand to the other.<br />

Dresden is the birthplace of several important inventions: the coffee filter, bra, SLR<br />

camera and toothpaste tube. We travel into the city on the train three days in a row and only<br />

on the last day do we get the tickets right! Even then we probably pay too much but at least<br />

we‟re legit. The locals whose help we enlist at the stations clearly have only slightly more<br />

idea than us when it comes to choosing the correct tickets from the machine. The guards on<br />

the trains are polite and forgiving. The train trip takes nine minutes, past enormous<br />

contrasting new and abandoned factories and apartment buildings.<br />

On the first day we walk around the old part of town <strong>with</strong> lots of German tourists,<br />

climb the tower of the Kreuzkirche, and get an expansive view in all directions. There‟s a<br />

superb wind trio playing classical music outside the recently restored Frauenkirche. The<br />

quality of the buskers here is astounding. We visit the huge bookshop Fachbuch, and in the<br />

three bays of books in English I find Kurt Vonnegut‟s “Slaughterhouse-Five” (a novel about<br />

22

the Allied bombing of Dresden, which he witnessed as a POW), Gunter Grass‟s<br />

autobiography “Peeling the Onion”, “Emma”, and “David Copperfield”. Oh joy!<br />

Back in Freital we have a long session at a LIDL supermarket, then dinner of salad<br />

made <strong>with</strong> very cheap and delicious salted salmon in oil and dill, salad greens, red onion, a<br />

can of corn, tomatoes, gherkins and mayonnaise. Deciding that we no longer need two<br />

folding chairs, John puts the <strong>larger</strong> one in the middle of the large grassy area next to our car<br />

park, as an installation. It has its back turned towards the bus and train stations. The next<br />

day when we return to the van someone has moved it a couple of meters and turned it round,<br />

and the following day it disappears. It‟s come a long way from a church fair in Newcastle<br />

three years ago.<br />

Next day we find another huge bookshop <strong>with</strong> an even better English section, and<br />

John buys “Firestorm: the Bombing of Dresden”, a recent collection of articles by academics<br />

which covers every aspect of the bombing. Our eyes are opened by a passage on<br />

reconstruction which compares architectural plans to a musical score. If a building is<br />

destroyed it can be rebuilt. There‟s a discussion of different philosophies of reconstruction<br />

under the Russians and post 1989. We buy postcards of the destroyed city which show miles<br />

of random walls <strong>with</strong> gaping holes where the windows were, and no roofs.<br />

We also visit the Zwinger, the most famous building in Dresden, built in the early 18 th<br />

century and consisting of a series of galleries, pavilions and gates surrounding a huge<br />

courtyard <strong>with</strong> lawns and fountains. The scale of the place is its most attractive feature for<br />

us, as the cherubs and highly decorative style of the architecture are not our cup of tea. We<br />

visit the Old Masters Gallery and see paintings by Titian, Vermeer, Durer and Velasquez, and<br />

tapestries by Raphael. We especially enjoy some paintings of Venice by Canaletto, and the<br />

paintings he did of Dresden when he was younger. The cityscape of the Elbe River below the<br />

Augustus Bridge is just the same now as it was when he painted it in 1748. The restored<br />

buildings have blackened stone next to new stone and we wonder if the original stone was<br />

blackened by coal smoke as in Newcastle, or by the bombing and subsequent firestorm.<br />

The buildings beside the river <strong>with</strong> the Augustus Bridge and promenade are a<br />

wonderful sight. They flow in a way quite unlike anything we‟ve seen before. The Allies‟<br />

decision to bomb this beautiful city is very hard to understand.<br />

My favourite sight in Dresden is the Furstenzug, a mural made of twenty four<br />

thousand Meissen porcelain tiles, showing a procession of the Saxon rulers over nine<br />

centuries, on horseback, <strong>with</strong> horses and men dressed in period costume. It‟s one hundred<br />

and eleven yards long, and towers above the goggling tourists on the street below. The detail<br />

is quite breathtaking. Apparently it was not damaged in the bombing.<br />

23

Furstenzug, Dresden<br />

On our walk from the station to the old town we pass many tacky hotels, modern<br />

buildings, and enormous building sites <strong>with</strong> cranes everywhere. It‟s a seething mass of road<br />

works and diversions as the city transforms itself. We‟re astounded to discover that the<br />

rebuilding of the old Dresden has only recently been completed.<br />

In the heart of the tourist area we see a stretched Trabant car and there are tiny toy<br />

Trabants for sale. Back at Freital there‟s a Trabant ambulance <strong>with</strong> a red light on top, and<br />

one up a pole. They were the main vehicle in East Germany in the Communist era, tiny cars<br />

<strong>with</strong> two stroke motors. Now they seem to be symbolic of the nostalgia some people feel for<br />

the GDR (Ostalgia).<br />

On our last day in Dresden it rains and we visit the Grosser Garten, a park <strong>with</strong> a<br />

palace, miniature railway and a zoo. We wander past beds of enormous dahlias and under<br />

beautiful trees. At the market we buy peaches and three little salamis which we hang in the<br />

back of the van.<br />

Next day we drive over to Neuestadt on the other side of the Elbe. We discover later<br />

that it was the Jewish quarter prior to the 1930s. We do three loads of washing and drying for<br />

ten Euros in a state of the art laundrette <strong>with</strong> twenty washing machines and a central control<br />

panel. Then we set out on the smooth concrete motorway for Weimar.<br />

24

So It Goes<br />

Motorway construction in Germany is impressive: thick pads of concrete. This one is<br />

being expanded, and we stay in fifth gear for miles, through flat to rolling country. We pass a<br />

strip of solar panels fifteen feet wide and at least half a mile long beside an industrial area,<br />

and lots of buzzards.<br />

We find a hospitable looking car park in Weimar, near an eighty year old outdoor<br />

pool. When we ask about a shower, John is shown into the men‟s changing area and I get<br />

taken to the sauna which isn‟t being used. It has a bar, spa pool, showers, and a large wooden<br />

bucket near the ceiling <strong>with</strong> a rope attached, which I‟m careful not to activate.<br />

Beautiful trees and a garden of sunflowers make this a very attractive place for<br />

camper vans. Sitting in the front seat that night, drinking a German Riesling from a bottle<br />

<strong>with</strong> a glass stopper and a label describing it as dry and mentioning limestone, we see a great<br />

spotted woodpecker on a larch tree just a few metres away.<br />

Next day we walk into the town centre which is a series of beautiful old squares, and a<br />

wide avenue, Schillerstrasse. The gardens and trees are exceptional. Outside the Bauhaus<br />

Museum a flower bed fifteen feet wide is densely packed, and every so often there‟s a<br />

fabulous transparent grass which is translucent like spraying water. A vacant patch of land is<br />

planted <strong>with</strong> white and purple flowers. The gingko tree is the town‟s emblem, after a famous<br />

poem by Goethe, and there‟s an avenue of young ones by the Bauhaus University. The place<br />

is packed <strong>with</strong> German tourists as there is both a cultural and a wine festival. We have a very<br />

cold glass of Riesling in a square at 11.30am then a picnic in the beautiful botanic gardens<br />

beside the Ilm River. There are many fabulous trees, mainly green beech and copper beech.<br />

Later we visit the site of the former Gestapo headquarters for the region. Some of the<br />

buildings have been demolished and the crushed building materials have been spread on the<br />

ground as part of the memorial.<br />

Weimar is famous for its cultural heritage, <strong>with</strong> a long list of writers, composers and<br />

artists resident in the 19 th and 20 th centuries, and the Bauhaus school of architecture founded<br />

here by Walter Gropius in 1919. It seems to be a Mecca for older Germans.<br />

Enjoying the hot weather we sit in the square <strong>with</strong> glasses of Federweisser (young<br />

wine <strong>with</strong> a low alcohol content, made from freshly pressed grape juice), and listen to a jazz<br />

band. Later, we walk back to the van and drive a short distance to the edge of town to the<br />

hundred year old German Bee Museum which shows the history of beekeeping <strong>with</strong> old<br />

hives, honey extraction machines, and information for the bee enthusiast, namely John. Our<br />

favourites are the very old hives made from hollow tree trunks carved and painted to look like<br />

<strong>larger</strong> than life people, <strong>with</strong> openings to let the bees in and out. A particularly risqué one<br />

from 1800 is in the form of a naked woman.<br />

25

Old Beehives<br />

The site of the Buchenwald concentration camp is just up the road from Weimar, on<br />

Ettersberg Hill. It‟s on limestone, looking out over flatter land to the south which reminds us<br />

of the North Downs in Surrey. John walks around a large part of the camp but I just look at<br />

the tall stone memorial. Nearly a quarter of a million people were brought here by the<br />

trainload, through Weimar, from 1937 until liberation in 1945. Over fifty thousand died in<br />

the main camp and its one hundred and thirty satellites, from overwork, disease, starvation,<br />

and execution. The sheer scale of it is overwhelming. We ponder the involvement of the<br />

people of Weimar. It must have intruded into their consciousness. From 1945 to 1950 the<br />

Russian occupiers imprisoned over one hundred and twenty thousand people in the camp, and<br />

over fifty thousand died.<br />

Driving back to town we stop at an outdoor shop to buy some cooking gas from a<br />

Canadian woman and a German man. They say a lot of their German customers are<br />

travelling to New Zealand, but they have never had New Zealanders in the shop before. They<br />

are very warm and friendly, in fact all the German people we talk to are outgoing and kind<br />

towards us.<br />

We can‟t leave Weimar <strong>with</strong>out visiting the small Bauhaus Museum which has some<br />

very fine pieces of furniture, and kitchen items like coffee pots and cups from that era of<br />

German design (1900 to 1930). Some items look quite contemporary.<br />

26

Later when I‟m in the back of the van making salt salmon and avocado salad, John<br />

reports that a camper bigger than our beach house in New Zealand has just driven into the car<br />

park. It‟s called Concorde. We always wonder what people do inside these vast vehicles<br />

Next morning when we get up there‟s a Polizei van parked nearby and by the time we<br />

return from our shower at the pool there are twelve Polizei vehicles in the car park,<br />

intermingled <strong>with</strong> the camper vans. It looks like one of our fellow travellers is giving some<br />

of them a coffee! They wander around in their overalls, very relaxed, and we assume that<br />

they‟re on some kind of exercise.<br />

We head southwest on motorways through Scots pine and fir forests which are being<br />

logged, enormous tunnels (the longest is five miles), and across massive viaducts. We‟re on<br />

our way to Stuttgart and our friend Vera Maria who we last saw a year ago when we lived<br />

and worked together in Surrey.<br />

27

Chapter 3 Germany, Czech Republic<br />

3 September – 20 September<br />

Marzipan Potatoes<br />

The number of lorries on German motorways is astounding, and probably an<br />

indication of the strength of German industry. South of Wurzburg we sit in a queue miles<br />

long, crawling slowly for an hour and a half. At one point we‟re sandwiched between a lorry<br />

from Slovakia and one from the Netherlands. It‟s a novel experience and we pass the time<br />

eating beautiful Gravenstein apples and watching buzzards and kestrels. But we decide to<br />

take more notice in future of the understated warning in the road atlas: “traffic jams<br />

possible”. We stop at Backnang, an hour‟s drive from Vera Maria‟s, and wander around in a<br />

state of shock after the tough drive. It‟s a beautiful town <strong>with</strong> the usual <strong>colour</strong>ful old timber<br />

framed buildings amongst modern shops. People are sitting outside at cafes enjoying the<br />

beautiful evening. We eat a delicious Chinese meal and chat to a man at the next table, an<br />

Iranian who has been in Germany for twenty years, unable to return home. The next day he<br />

will see his brother for the first time since he left Iran.<br />

Sculpture <strong>with</strong> Graffiti, Backnang<br />

Next day we‟re in a landscape where apples dominate. Old trees heavy <strong>with</strong> fruit,<br />

some <strong>with</strong> branches propped up, appear to be growing wild, and there are numerous orchards.<br />

It‟s beautiful green rolling country <strong>with</strong> steep volcanic hills and the occasional castle. The<br />

fields and orchards have little huts, and jays are about.<br />

28

As we approach Vera Maria‟s she phones us to give directions. Then suddenly there<br />

she is by the side of the road on a bicycle, waving. It‟s fantastic to see her after more than a<br />

year.<br />

She leads the way by bicycle to her parents‟ place in Beuren, a little town of gorgeous<br />

old houses in perfect shape. It‟s a converted stable, on four levels, <strong>with</strong> beams several<br />

centuries old. A pair of swallows has a nest over the front door, returning each year on the<br />

same day. Vera Maria‟s mother gives us coffee in the garden, then takes us to her orchard a<br />

couple of minutes drive away: five acres of very old cherry and apple trees, <strong>with</strong> ten<br />

beehives, flowers, herbs and vegetables. There‟s even a shed and a campfire. We love it and<br />

could happily stay the night in the shed and cook on the campfire! She and John have a long<br />

discussion on the ways of bees.<br />

After a delicious lunch in the garden Vera Maria takes us to the local castle Burg<br />

Hohenneuffen, high on a forest covered hill, where there‟s a falconry display. The falconers<br />

are in Medieval costume, <strong>with</strong> a red and white striped tent. The birds sweep low over our<br />

heads as they fly in to catch pieces of meat, resplendent in their leather harnesses and hoods.<br />

The view from the castle is amazing, over cultivated land, forest and towns. It reminds us of<br />

the panoramas we‟ve seen from the town hall towers in Tuscany, a patchwork of land that has<br />

been cultivated for centuries, so different from the raw frontier landscape of home.<br />

That night we go out for a traditional Schwabian meal at a little restaurant called<br />

Brunnenstube a couple of doors away from Vera Maria‟s place. It‟s run by a husband and<br />

wife and appears to be in their lounge. John and I both have Zwiebelrostbraten mit<br />

Sauerkraut und Schupfnudeln, very tender roast beef <strong>with</strong> sauerkraut and a special potato<br />

dish. Huge servings and we eat well.<br />

Next day Vera Maria takes us into Stuttgart, and on the way we visit her old riding<br />

school where she learnt to ride cute little shaggy-maned Icelandic ponies. We also have a<br />

look at her old school Waldorfschule Uhlandshohe Stuttgart, the oldest Steiner school in the<br />

world, <strong>with</strong> its lovely buildings from several different eras.<br />

We eat a delicious lunch at a cafe, smoked salmon for me, and for John special white<br />

sausages from Munich which come floating in a tureen of hot water. He shows admirable<br />

self control when they appear. After that we‟re off to the State Gallery which has Picassos<br />

and also beautiful local paintings from altar pieces. That‟s when the unfortunate wheel of<br />

fortune incident occurs....<br />

Vera Maria and I are sauntering into a gallery a few paces behind John when an<br />

ominous clunking reverberates around the place. John has reached out and given a wheel of<br />

fortune style sculpture attached to the wall a quick twirl. Little blocks of wood or marbles<br />

rattle as they change position, just as the artist intended. As Vera Maria and I converge on<br />

John I notice a sign on the wall saying “Bitte ... something”, so I work out that it must say<br />

29

“please do not touch”. Immediately two guards appear, looks of horror on their faces. John<br />

does a very good job of looking contrite. Vera Maria talks fast, in German of course, and we<br />

pick up the word “Englander”, like this is his “Get out of Jail Free” card! The guards stand<br />

their ground, and one says that she doesn‟t know how she is going to tell her boss what has<br />

happened. It‟s very tense. Vera Maria persists <strong>with</strong> her explanation and manages to smooth<br />

things over, very impressive for a twenty year old, and we are so grateful. We make a quick<br />

exit to the next room and John explains to us that he‟d read the write up in English where the<br />

artist said that he intended for it to be spun to change the pattern. Since the guards are so<br />

upset, Vera Maria decides to go back and apologise to them again. The senior guard confides<br />

that she‟s always wanted to give the sculpture a twirl herself!<br />

We all calm down <strong>with</strong> a walk around the Schlossplatz a glorious square <strong>with</strong><br />

fountains and trees, surrounded by old buildings. Then we sample some high end German<br />

consumer culture <strong>with</strong> a visit to a fabulous department store <strong>with</strong> a mezzanine floor crammed<br />

<strong>with</strong> desirable household items, and on the ground floor a wonderful food market.<br />

That night over a tasty pancake dinner Vera Maria‟s father patiently answers all our<br />

questions. We find out that Danzig in Gunter Grass‟s “Peeling the Onion” is now Gdansk in<br />

Poland, and that Germany lost a large chunk of territory to Poland after WW2. The borders<br />

in Europe seem so arbitrary, even temporary.<br />

That night John picks up a radio station from the huge American military base we saw<br />

on our drive south. The announcer says “If you look after the eagle, the eagle will look after<br />

you”.<br />

Our visit <strong>with</strong> Vera Maria‟s family is over all too soon, and next day we set out <strong>with</strong> a<br />

delicious packed lunch, jars of honey, and apples, and memories of melt in the mouth apple<br />

strudel. Our goal is to travel west towards the Black Forest. In a field I see a kite which has<br />

a sharp fork in the tail, very different and distinctive in its flight compared <strong>with</strong> the<br />

ubiquitous buzzards. It‟s only an hour‟s drive to Calw on the edge of the Black Forest, a very<br />

old town famous for the writer Herman Hesse who spent the early part of his life there. It‟s<br />

in a valley surrounded by forest, mainly conifer <strong>with</strong> some deciduous.<br />

We park beside the railway line, beneath cliffs covered in tall slim conifers which<br />

tower above us. I see a spotted woodpecker and hear a nuthatch. Our clean laundry is still<br />

slightly damp so we put up a clothesline and hang it all out in the sun and wind. There are a<br />

few people around but no-one seems to care about our Gypsy ways. We‟re trying to avoid<br />

the composting washing situation that John discovered a few days earlier. Reaching into his<br />

clean clothes he discovered that they were hot and moist, put away damp from the drier then<br />

sweating in the heat of the back of the van.<br />

30

The Gypsies Arrive in Calw<br />

We buy some supplies at the supermarket and I discover marzipan potatoes, delicious<br />

little soft balls of marzipan rolled in cocoa. That night I read that Gunter Grass had marzipan<br />

potatoes shortly after signing up <strong>with</strong> the army at the age of seventeen.<br />

A Walk in the Black Forest<br />

Next morning we get up early to go to a car boot sale which turns out to be pretty<br />

basic - <strong>full</strong> of bad taste junk. We explore Calw while we wait for the Herman Hesse Museum<br />

to open. The Nagold River runs right through town, parallel to the main street. It‟s crossed<br />

by the Nikolaus Bridge, Calw‟s most important landmark, built around 1400 and renovated in<br />

1863 and 1926. The tiny chapel of St Nikolaus is built on the central pillar. This was<br />

Herman Hesse‟s favourite place, and there‟s a bronze statue of him looking towards the<br />

chapel.<br />

The town is <strong>full</strong> of old stone buildings and little nooks and crannies to explore<br />

including one house <strong>with</strong> a living roof of grass and cacti. Herman Hesse is the main tourist<br />

drawcard but unfortunately the Museum has captions in German only. We enjoy the<br />

fascinating collection of <strong>photos</strong>, letters, manuscripts, paintings, furniture and memorabilia,<br />

and the serene atmosphere. John is absolutely thrilled to make the pilgrimage here and poses<br />