Download This File - The Free Information Society

Download This File - The Free Information Society

Download This File - The Free Information Society

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

D R U G E N F O R C E M E N T A D M I N I S T R A T I O N<br />

a tradition of excellence<br />

1973-2003<br />

<strong>This</strong> book is dedicated to those DEA employees<br />

and their families who, with honor and courage,<br />

have led the way for those who follow.

Table of Contents<br />

1970-1975......................3<br />

1975-1980.....................24<br />

1980-1985.....................43<br />

1985-1990.....................58<br />

1990-1994.....................75<br />

1994-1998.....................90<br />

1998-2003...................115<br />

Acknowledgments<br />

DEA gratefully acknowledges<br />

the offices and employees who<br />

contributed photos, historical<br />

material and stories to this 30th<br />

Anniversary History Book.<br />

Many thanks to those people<br />

who helped create, compile and<br />

edit this book.

D R U G E N F O R C E M E N T A D M I N I S T R A T I O N<br />

D R U G E N F O R C E M E N T A D M I N I S T R A T I O N<br />

3<br />

In the spring and summer of 1973,<br />

the U.S. House of Representatives and<br />

the U.S. Senate heard months of<br />

testimony on Richard Nixon’s Reorganization<br />

Plan Number 2, which proposed<br />

the creation of a single federal<br />

agency to consolidate and coordinate<br />

the government’s drug<br />

control activities.

Drug use had not reached its alltime<br />

peak, but the problem was serious<br />

enough to warrant a serious<br />

response.<br />

<strong>The</strong> long, proud, and honorable tradition of federal drug law<br />

enforcement began in 1915 with the Bureau of Internal Revenue.<br />

In the following decades, several federal agencies had<br />

drug law enforcement responsibilities. By the 1960s, the two<br />

agencies charged with drug law enforcement were the Bureau<br />

of Drug Abuse Control (BDAC) and the federal Bureau of<br />

Narcotics (FBN). It was during this period that America underwent<br />

a significant change. <strong>The</strong> introduction of drugs into<br />

American culture and the efforts to “normalize” drug use<br />

started to take a terrible toll on the nation. Nevertheless, American<br />

children could still walk to school in relative safety, worrying<br />

only about report cards or the neighborhood bully. Today<br />

however, as children approach their schools, they see<br />

barbed wire, metal detectors, and signs warning drug dealers<br />

that school property is a “drug free zone.” In too many communities,<br />

drug dealers and gunfire force decent, law-abiding<br />

citizens to seek refuge behind locked doors.<br />

In 1960, only four million Americans had ever tried drugs.<br />

Currently, that number has risen to over 74 million. Behind<br />

these statistics are the stories of countless families, communities,<br />

and individuals adversely affected by drug abuse and<br />

drug trafficking.<br />

Prior to the 1960s, Americans did not see drug use as acceptable<br />

behavior, nor did they believe that drug use was an inevitable<br />

fact of life. Indeed, tolerance of drug use resulted in<br />

terrible increases in crime between the 1960s and the early<br />

1990s, and the landscape of America has been altered forever.<br />

By the early 1970s, drug use had not yet reached its all-time<br />

peak, but the problem was sufficiently serious to warrant a<br />

serious response. Consequently, the Drug Enforcement Administration<br />

(DEA) was created in 1973 to deal with America’s<br />

growing drug problem.<br />

At that time, the well-organized international drug trafficking<br />

syndicates headquartered in Colombia and Mexico had not<br />

yet assumed their place on the world stage as the preeminent<br />

drug suppliers. All of the heroin and cocaine, and most of the<br />

marijuana that entered the United States was being trafficked<br />

by lesser international drug dealers who had targeted cities<br />

and towns within the nation. Major law enforcement investigations,<br />

such as the French Connection made by agents in<br />

the DEA’s predecessor agency, the Bureau of Narcotics and<br />

Dangerous Drugs (BNDD), graphically illustrated the complexity<br />

and scope of America’s heroin problem.<br />

4<br />

In the years prior to 1973, several important developments<br />

took place which would ultimately have a significant impact<br />

on the DEA and federal drug control efforts for years to come.<br />

By the time that the DEA was created by Executive Order in<br />

July 1973 to establish a single unified command, America was<br />

beginning to see signs of the drug and crime epidemic that lay<br />

ahead. In order to appreciate how the DEA has evolved into<br />

the important law enforcement institution it is today, it must<br />

be understood that many of its programs have roots in predecessor<br />

agencies.<br />

On December 14, 1970, at the White House, the<br />

International Narcotic Enforcement Officers’ Association<br />

(INEOA) presented to President Nixon<br />

a “certificate of special honor in recognition of the<br />

outstanding loyalty and contribution to support narcotic<br />

law enforcement.” Standing with President Nixon were<br />

(from left) John E. Ingersoll, Director of BNDD; John<br />

Bellizzi, Executive Director of INEOA; and Matthew<br />

O’Conner, President of INEOA.<br />

DEA Special Agents DEA Budget<br />

1973..........1,470 1973..........$74.9 million<br />

1975..........2,135 1975..........$140.9 million

BNDD<br />

John E. Ingersoll<br />

Director, BNDD<br />

1968-1973<br />

John E. Ingersoll served as Director of the U.S. Bureau<br />

of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (BNDD) from 1968<br />

until 1973. He began his career as a patrolman and<br />

then sergeant for the Oakland, California, Police<br />

Department from 1956 until 1961, when he became the<br />

Director of Field Services for the International<br />

Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP). He served with<br />

the IACP until 1966, when he became the chief of<br />

police for Charlotte, North Carolina, until his appointment<br />

as Director of BNDD in 1973. He was also the<br />

U.S. Representative to the United Nations Commission<br />

on Narcotic Drugs from 1969 to 1973. From 1973 to<br />

1993, Mr. Ingersoll worked for the IBM Corporation,<br />

serving as Director of Security for IBM’s International<br />

Business Unit and the IBM World Trade Subsidiary.<br />

Since April 1993, he has worked as an independent<br />

consultant to business and government.<br />

In 1968, with the introduction into Congress of Reorganization<br />

Plan No. 1, President Johnson proposed combining two<br />

agencies into a third new drug enforcement agency. <strong>The</strong> action<br />

merged the Bureau of Narcotics, in the Treasury Department,<br />

which was responsible for the control of marijuana and<br />

narcotics such as heroin, with the Bureau of Drug Abuse<br />

Control (BDAC), in the Department of Health, Education,<br />

and Welfare, which was responsible for the control of dangerous<br />

drugs, including depressants, stimulants, and hallucinogens,<br />

such as LSD. <strong>The</strong> new agency, the Bureau of Narcotics<br />

and Dangerous Drugs (BNDD), was placed under the<br />

Department of Justice, which is the government agency primarily<br />

concerned with federal law enforcement.<br />

5<br />

Before the creation of<br />

the DEA in 1973,<br />

multiple law enforcement<br />

and intelligence organizations<br />

carried out federal<br />

drug enforcement policies.<br />

According to the Reorganization Plan, “the Attorney General<br />

will have full authority and responsibility for enforcing the<br />

federal laws relating to narcotics and dangerous drugs. <strong>The</strong><br />

BNDD, headed by a Director appointed by the Attorney General,<br />

would:<br />

(1) consolidate the authority and preserve the experience and<br />

manpower of the Bureau of Narcotics and Bureau of<br />

Drug Abuse Control;<br />

(2) work with state and local governments in their crackdown<br />

on illegal trade in drugs and narcotics, and help to train<br />

local agents and investigators;<br />

(3) maintain worldwide operations, working closely with other<br />

nations, to suppress the trade in illicit narcotics and<br />

marijuana; and<br />

(4) conduct an extensive campaign of research and a nationwide<br />

public education program on drug abuse and its<br />

tragic effects.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> BNDD became the primary drug law enforcement agency<br />

and concentrated its efforts on both international and interstate<br />

activities. By 1970, the BNDD had nine foreign offices—in<br />

Italy, Turkey, Panama, Hong Kong, Vietnam, Thailand,<br />

Mexico, France, and Colombia—to respond to the dynamics<br />

of the drug trade. Domestically, the agency initiated<br />

a task force approach involving federal, state, and local officers.<br />

<strong>The</strong> first such task force was set up in New York City.<br />

In addition, the BNDD established Metropolitan Enforcement<br />

Groups, which were based on the regional enforcement<br />

concept that provided for sharing undercover personnel,<br />

equipment, and other resources from different jurisdictions.<br />

<strong>The</strong> BNDD provided training and operational support for<br />

these units. By February 1972, the BNDD’s agent strength<br />

had grown to 1,361, its budget had more than quadrupled,<br />

and its foreign and domestic arrest totals had doubled. In<br />

addition, the BNDD had regulatory control over more than<br />

500,000 registrants licensed to distribute licit drugs, and it<br />

had six sophisticated forensic labs.

ABOVE: With Proclamation 3981, President<br />

Richard Nixon designated the week of May 24 as<br />

Drug Abuse Prevention Week in 1970.<br />

BELOW: Vol.III No.I BNDD Bulletin<br />

6<br />

ODALE<br />

Myles J. Ambrose<br />

Director, ODALE<br />

1972-1973<br />

Myles J. Ambrose<br />

Director<br />

tice by Executive Order 11641.<br />

ODALE<br />

On January 28, 1972, President Nixon created the Office of Drug<br />

Abuse Law Enforcement (ODALE), within the Department of Jus<br />

<strong>The</strong> Office was headed by Myles<br />

Ambrose, who had served as U.S. Commissioner of Customs at the<br />

Treasury Department from 1969 until 1972. As Director of ODALE,<br />

Mr. Ambrose served as Special Assistant Attorney General and as<br />

Special Consultant to the President. ODALE was established for an<br />

18-month period as an experimental approach to the problem of<br />

drug abuse in America. During that time, ODALE conducted intensive<br />

operations throughout the country, then evaluated their impact<br />

on heroin trafficking at the middle and lower distribution levels.<br />

ODALE’s objective was “to bring substantial federal resources to<br />

bear on the street-level heroin pusher.”<br />

Organizationally, the office drew heavily upon the expertise of existing<br />

federal law enforcement agencies to coordinate and focus resources<br />

and manpower. ODALE programs involved close, fulltime<br />

working relationships among participating federal, state, and<br />

local officers who, while reporting administratively to their respective<br />

agencies, took direction from ODALE.<br />

ODALE provided common office space for the personnel assigned<br />

to it, and all salaries and other costs were borne by the parent<br />

organization on a nonreimbursable basis. Justice Department entities<br />

involved included the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous<br />

Drugs, Immigration and Naturalization Service, U.S. Marshals<br />

Service, the Tax Division, and offices of the U.S. Attorneys in the<br />

cities where the heroin problem was concentrated. Treasury Department<br />

entities included the Internal Revenue Service, the Bureau<br />

of Customs, and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms. In<br />

addition, non-law enforcement federal agencies contributing personnel<br />

and other assistance included the Atomic Energy Commission,<br />

the U.S. Air Force, the Environmental Protection Agency, and<br />

the Interstate Commerce Commission.<br />

By 1972, ODALE headquarters had 79 authorized positions and<br />

nine regional offices. It targeted street-level drug dealers through<br />

special grand juries and pooled intelligence data for federal, state,<br />

and local law enforcement agencies. Regional offices were based in<br />

Los Angeles, Denver, Houston, Kansas City, Chicago, Cleveland,<br />

Atlanta, New York City, and Philadelphia. ODALE task forces<br />

operated in 38 target cities through investigation-prosecution teams<br />

and special grand juries which considered indictments.<br />

In 1998, Mr. Ambrose was with Arter and Hadden, LLP, in Washington,<br />

D.C.

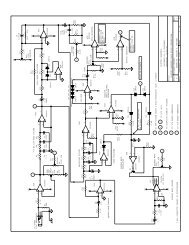

Bureau of Prohibition<br />

Department of the Treasury<br />

1927-1930<br />

Bureau of Internal Revenue<br />

Department of the Treasury<br />

1915-1927<br />

Bureau of Narcotics<br />

Department of the Treasury<br />

1930-1968<br />

Bureau of Drug Abuse Control<br />

Food & Drug Administration<br />

Dept. of Health, Education &<br />

Welfare<br />

1966-1968<br />

Foreign Offices Opened<br />

DEA Genealogy<br />

Bureau of Narcotics and<br />

Dangerous Drugs<br />

Department of Justice<br />

1968-1973<br />

7<br />

U.S. Customs Service<br />

(Drug Investigations)<br />

Department of the Treasury<br />

Office of National Narcotics<br />

Intelligence<br />

Department of Justice<br />

Office of Drug Abuse Law<br />

Enforcement<br />

(ODALE)<br />

Department of Justice<br />

Narcotics Advance Research<br />

Management Team<br />

Executive Office of the President<br />

Drug Enforcement<br />

Administration<br />

Department of Justice<br />

1973<br />

1960 Paris, France<br />

1960 Rome, Italy 1970 Madrid, Spain 1972 New Dehli, India<br />

1961 Istanbul, Turkey 1970 Manila, Philippines 1972 Panama City, Panama<br />

1963 Bangkok, Thailand 1970 Santiago, Chile 1972 Quito, Ecuador<br />

1973 Islamabad, Pakistan<br />

1963 Mexico City, Mexico 1970 Tokyo, Japan<br />

1963 Monterrey, Mexico 1971 Ankara, Turkey 1973 Mazatlan, Mexico<br />

1963 Hong Kong 1971 Asuncion, Paraguay 1973 Ottawa, Canada<br />

1963 Singapore 1971 Caracas, Venezuela 1974 Guayaquil, Equador<br />

1966 Lima, Peru 1971 Chiang Mai, Thailand 1974 Karachi, Pakistan<br />

1966 Seoul, S. Korea 1971 Brasilia, Brazil 1974 Kingston. Jamaica<br />

1969 Guadalajara, Mexico 1971 Hermosillo, Mexico 1974 San Jose, Costa Rica<br />

1974 Songkhla, Thailand<br />

1970 Buenos Aires, Argentina 1971 Milan, Italy<br />

1970 Frankfurt, Germany 1972 Bogota, Colombia 1974 <strong>The</strong> Hague, Netherlands<br />

1974 Vienna, Austria<br />

1970 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 1972 Bonn, Germany<br />

1970 London, England 1972 Brussels, Belgium<br />

1972 La Paz, Bolivia

New York Task Force (1970)<br />

1970: Bruce E. Jensen, Chief,<br />

New York Drug Enforcement<br />

Task Force, explained how<br />

the prototype of the Task<br />

Force began with 43<br />

investigators from<br />

federal, state, and city<br />

personnel, along<br />

with a small<br />

support staff.<br />

In 1970, the first narcotics task force was established in<br />

New York under the auspices of the BNDD to maximize<br />

the impact of cooperating federal, state, and local<br />

law enforcement elements working on complex drug<br />

investigations. Bruce Jensen, former chief of the New<br />

York Drug Enforcement Task Force, described it “not<br />

as a monument...but a foundation firm enough to withstand<br />

the test of time.” At the time, heroin was a significant<br />

problem, and law enforcement officials were<br />

seeking ways to reduce availability and identify and prosecute<br />

those responsible for heroin trafficking. Federal,<br />

state, and municipal law enforcement organizations put<br />

aside rivalries and agreed to collaborate within the framework<br />

of the New York Joint Task Force. <strong>The</strong> task force<br />

program also became an essential part of the DEA’s<br />

operations and reflected the belief that success is only<br />

possible through cooperative investigative efforts. <strong>The</strong><br />

BNDD, the New York State Police, and the New York<br />

City Police Department contributed personnel to work<br />

with Department of Justice lawyers and support staff.<br />

<strong>The</strong> rationale behind the Task Force was that each representative<br />

brought different and valuable perspectives<br />

and experiences to the table and that close collaboration<br />

among the membership could result in cross-training<br />

and the sharing of expertise. Since then, the Task<br />

Force expanded from the original 43 members. In 1971<br />

it increased to 172 members, and by 2003 it had 211 law<br />

enforcement personnel assigned.<br />

8<br />

In February 1972, the New York Joint Task Force seized<br />

$967,000 during a Bronx arrest. New York City Police<br />

Captain Robert Howe (left) and BNDD agent <strong>The</strong>odore L.<br />

Vernier are shown counting the money.<br />

In April 1973, New York City Police and federal agents<br />

arrested 69 drug traffickers who were believed to be<br />

capable of distributing 100 kilograms of cocaine a week.

Comprehensive Drug Abuse<br />

Prevention and Control Act<br />

(1970)<br />

In response to America’s growing drug problem, Congress<br />

passed the Controlled Substances Act (CSA), Title<br />

II of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and<br />

Control Act of 1970. It replaced more than 50 pieces of<br />

drug legislation, went into effect on May 1, 1971, and<br />

was enforced by the BNDD, the DEA’s predecessor<br />

agency. <strong>This</strong> law, along with its implementing regulations,<br />

established a single system of control for both narcotic<br />

and psychotropic drugs for the first time in U.S.<br />

history.<br />

It also established five schedules that classify controlled<br />

substances according to how dangerous they are, their<br />

potential for abuse and addiction, and whether they possess<br />

legitimate medical value. Thirty three years later,<br />

the CSA, though amended on several occasions, remained<br />

the legal framework from which the DEA derived<br />

its authority.<br />

Members of a 1972 Compliance Investigator class were<br />

trained in drug identification.<br />

Diversion Control Program (1971)<br />

1970: BNDD’s Compliance Investigators frequently found<br />

that pharmacy violators of narcotics and drug laws also<br />

lacked professional responsibility in other areas. <strong>The</strong><br />

unsavory sanitary conditions of the storage room pictured<br />

here were found during a BNDD pharmacy investigation<br />

in Louisiana.<br />

In the 1969 U.S. Senate hearings on the Controlled Sub- Thus, the controls mandated by the CSA encompassed<br />

stances Act (CSA), witnesses estimated that 50 percent scheduling, manufacturing, distributing, prescribing, imof<br />

the amphetamine being produced annually during the porting, exporting, and other related activities. <strong>The</strong>y also<br />

1960s had found its way into the illicit drug traffic. Fol- provided the BNDD with the legal tools needed to deal<br />

lowing the passage of the CSA in 1970, it was impera- with the diversion problem as it existed at that time. Prior<br />

tive that the U.S. Government establish mechanisms to to the CSA, investigations involving the diversion of leensure<br />

that this growing diversion of legal drugs into the gitimate pharmaceuticals were conducted solely by speillicit<br />

market be addressed. In 1970, over two billion dos- cial agents as part of their enforcement activities. Howage<br />

units of amphetamine and methamphetamine were ever, shortly after implementation of the CSA, BNDD<br />

producing excessive amounts of pharmaceuticals. management recognized that the investigation of diver<br />

9

sion cases differed significantly from investigation of traditional<br />

narcotics cases.<br />

In late 1971, the Compliance Program, later renamed<br />

the Diversion Control Program, was created to provide<br />

a specialized work force that could focus exclusively on<br />

the diversion issue and take full advantage of the controls<br />

and penalties established by the CSA.<br />

<strong>This</strong> work force developed an in-depth knowledge of<br />

the legitimate pharmaceutical industry and the investigative<br />

techniques needed to make cases that were essential<br />

to investigate legitimate organizations and professionals<br />

engaged in drug diversion. <strong>The</strong> program was<br />

placed under the BNDD’s Office of Enforcement and<br />

staffed by compliance investigators, later called diversion<br />

investigators.<br />

<strong>The</strong> first major challenge these investigators faced was<br />

the extraordinary amount of amphetamines and barbiturates<br />

being diverted at the manufacturer and distributor<br />

levels. <strong>The</strong> year the CSA went into effect, over 2,000<br />

provisional registrations were issued to manufacturers<br />

and distributors who had been operating under the<br />

Harrison Narcotics Act of 1914 and the Drug Abuse<br />

Control Amendments. In order to stem the diversion<br />

problem, it was necessary to enlist the support of manufacturers,<br />

wholesalers, distributors, and pharmacists for<br />

regular inspections of records and premises. It was also<br />

necessary to establish a system of registration to ensure<br />

that law enforcement investigators had access to the<br />

Prevent<br />

drug abuse<br />

8c United Staes Postage<br />

10<br />

records and physical plants maintained by those responsible<br />

for the manufacture and distribution of drugs.<br />

<strong>The</strong> first inspections of registrants revealed instances<br />

where drug handlers were operating out of basements<br />

and garages with little or no security and were unable to<br />

account for the receipt or distribution of the drugs they<br />

handled. In order to ensure that the diversion of dangerous<br />

drugs did not continue, it was critical that meaningful<br />

punitive measures could be taken against the minority<br />

of registrants responsible for the diversion of drugs<br />

into the illegal market. Offenders were given the option<br />

of either surrendering their controlled substances registration<br />

or instituting strict controls necessary to prevent<br />

diversion in their offices and organizations. Establishments<br />

and individuals who continued to violate the law<br />

were subject to criminal, civil, or administrative actions.<br />

As the program developed, it became clear that the diversion<br />

of drugs was not simply a domestic issue. It became<br />

essential that controls on international supplies of<br />

legal drugs also be established. In the early 1970s, there<br />

were several examples of foreign subsidiaries of U.S.<br />

drug manufacturers becoming the main suppliers of illicit<br />

drugs, such as amphetamine, to the black market in<br />

the United States. Through revocation of drug manufacturers’<br />

export licenses, the BNDD, and then the DEA,<br />

were able to successfully reduce the influx of illegal licit<br />

drugs into the United States.<br />

Drug Abuse Prevention<br />

Commemorative<br />

U.S. Postage Stamp<br />

On October 4, 1971, the U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp<br />

to commemorate the Prevention efforts of the Bureau of<br />

Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs. It was designed by<br />

Suzanne Rice and K. Gardner Perine of the BNDD Graphic<br />

Section.

French Connection<br />

French Connection (1971-1972)<br />

Diplomat-trafficker Mauricio Rosales, At Idlewild Airport (now JFK) in New Bureau of Narcotics agents who worked<br />

the Guatemalan ambassador to Belgium, York, Etienne Tarditi, a French Corsican on Rosales case pose with suitcases<br />

was using his diplomatic status to trafficker (trenchcoat),. He was coming filled with heroin.<br />

smuggle in 100 kilos of heroin in these to meet his drug courier, help deliver<br />

three suitcases. heroin to New York gangsters, and collect<br />

payment.<br />

Illegal heroin labs were first discovered near Marseilles, France,<br />

in 1937. <strong>The</strong>se labs were run by the legendary Corsican gang<br />

leader Paul Carbone. For years, the French underworld had<br />

been involved in the manufacturing and trafficking of illegal<br />

heroin abroad, primarily in the United States. It was this heroin<br />

network that eventually became known as the French Connection.<br />

Historically, the raw material for most of the heroin consumed<br />

in the United States came from Turkey. Turkish farmers<br />

were licensed to grow opium poppies for<br />

sale to legal drug companies,<br />

but many sold<br />

their excess to<br />

the underworld<br />

market, where it<br />

was manufactured<br />

into heroin and transported<br />

to the United<br />

States. It was refined in Corsican laboratories in Marseilles,<br />

one of the busiest ports in the western Mediterranean.<br />

Marseilles served as a perfect shipping point for all types of<br />

illegal goods, including the excess opium that Turkish farmers<br />

cultivated for profit.<br />

<strong>The</strong> convenience of the port at Marseilles and the frequent<br />

arrival of ships from opium-producing countries made it easy<br />

to smuggle the morphine base to Marseilles from the Far East<br />

or the Near East. <strong>The</strong> French underground would then ship<br />

large quantities of heroin from Marseilles to Manhattan,<br />

New York.<br />

11<br />

<strong>The</strong> first significant post-World War II seizure was made in<br />

New York on February 5, 1947, when seven pounds of heroin<br />

were seized from a Corsican seaman disembarking from a vessel<br />

that had just arrived from France.<br />

It soon became clear that the French underground was increasing<br />

not only its participation in the illegal trade of opium,<br />

but also its expertise and efficiency in heroin trafficking. On<br />

March 17, 1947, 28 pounds of heroin were found on the French<br />

liner, St. Tropez. On January 7, 1949, more than 50 pounds of<br />

opium and heroin were seized on the French ship,<br />

Batista.<br />

<strong>The</strong> first major French Connection<br />

case occurred in 1960. In<br />

June, an informant told a drug<br />

agent in Lebanon that Mauricio<br />

Rosal, the Guatemalan Ambassador<br />

to Belgium, the Netherlands,<br />

and Luxembourg, was smuggling<br />

morphine base from Beirut, Lebanon, to Marseilles.<br />

Narcotics agents had been seizing about 200 pounds of heroin<br />

in a typical year, but intelligence showed that the Corsican<br />

traffickers were smuggling in 200 pounds every other week.<br />

Rosal alone, in one year, had used his diplomatic status to<br />

bring in about 440 pounds.<br />

<strong>The</strong> FBN’s 1960 annual report estimated that from 2,600<br />

to 5,000 pounds of heroin were coming into the United<br />

States annually from France. <strong>The</strong> French traffickers<br />

continued to exploit the demand for their illegal product,

and by 1969, they were supplying the United States with<br />

80 to 90 percent of the heroin consumed by addicts. <strong>The</strong><br />

heroin they supplied was approximately 85 percent pure.<br />

Because of this increasing volume, heroin became readily<br />

available throughout the United States. In an effort to<br />

limit the source, U.S. officials went to Turkey to negotiate<br />

the phasing out of opium production. Initially, the<br />

Turkish Government agreed to limit their opium production<br />

starting with the 1968 crop.<br />

Following five subsequent years of concessions, combined<br />

with international cooperation, the Turkish government<br />

finally agreed in 1971 to a complete ban on the<br />

growing of Turkish opium, effective June 30, 1972.<br />

During these protracted negotiations, law enforcement<br />

personnel went into action. One of the major roundups<br />

began on January 4, 1972, when BNDD agents and<br />

French authorities seized 110 pounds of heroin at the<br />

Paris airport. Subsequently, traffickers Jean-Baptiste<br />

.Croce and Joseph Mari were arrested in Marseilles.<br />

In February 1972, French traffickers offered a U.S. Army Sergeant<br />

$96,000 to smuggle 240 pounds of heroin into the United<br />

States. He informed his superior who in turn notified the<br />

BNDD. As a result of this investigation, five men in New<br />

York and two in Paris were arrested with 264 pounds of heroin,<br />

February 14, 1973: A 20-kilo heroin seizure in Paris,<br />

France. Pictured left to right are,S/A Pierre Charette, S/A<br />

Kevin Finnerty, and French anti-drug counterparts.<br />

12<br />

From a 1973 French Connection seizure in France, (pictured<br />

above) are 210 pounds of heroin worth $38 million .<br />

which had a street value of $50 million. In a 14-month period,<br />

starting in February 1972, six major illicit heroin laboratories<br />

were seized and dismantled in the suburbs of Marseilles by<br />

French national narcotics police in collaboration with U.S.<br />

drug agents. On February 29, 1972, French authorities seized<br />

the shrimp boat, Caprice de Temps, as it put to sea near<br />

Marseilles heading towards Miami. It was carrying 415 kilos<br />

of heroin. Drug arrests in France skyrocketed from 57 in 1970<br />

to 3,016 in 1972. <strong>The</strong> French Connection investigation demonstrated<br />

that international trafficking networks were best<br />

disabled by the combined efforts of drug enforcement<br />

agencies from multiple countries. In this case, agents<br />

from the United States, Canada, Italy, and France had<br />

worked together to achieve success.<br />

First Female Special Agents<br />

1933: Mrs. Elizabeth Bass was appointed the first of<br />

many female narcotics agents in the United States and<br />

served as District Supervisor in Chicago. A longtime<br />

friend of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, she played a<br />

prominent role in gaining political support for the<br />

Uniform Narcotic Drug Act.<br />

1971: <strong>The</strong> DEA’s predecessor agency, the BNDD,<br />

became one of the first federal agencies to implement<br />

a program for hiring female special agents.<br />

1973: Ms. Mary Turner became the first female DEA<br />

special agent to graduate from the DEA’s training<br />

program. She finished first in her class.<br />

1974: Twenty-three female special agents were<br />

working in DEA field offices throughout the United<br />

States.

Creation of the DEA (July 1, 1973)<br />

In 1973, President<br />

Richard Nixon<br />

signed the Executive<br />

Order which created<br />

the DEA.<br />

No. 11727<br />

July 10, 1973, 38 F.R. 18357<br />

DRUG LAW ENFORCEMENT<br />

Reorganization Plan No. 2 of 1973, which becomes effective on July 1, 1973, among other things establishes a Drug Enforcement<br />

Administration in the Department of Justice. In my message to the Congress transmitting that plan, I stated that all functions of the Office<br />

for Drug Abuse Law Enforcement (established pursuant to Executive Order No. 11641 of January 28, 1972) and the Office of National<br />

Narcotics Intelligence (established pursuant to Executive Order No. 16676 of July 27, 1972) would, together with other related functions be<br />

merged in the new Drug Enforcement Administration.<br />

NOW, THEREFORE, by virtue of the authority vested in me by the Constitution and laws of the United States, including section 5317 of<br />

title 5 of the United States Code, as amended, it is hereby ordered as follows:<br />

Section 1. <strong>The</strong> Attorney General, to the extent permitted by law, is authorized to coordinate all activities of executive branch departments<br />

and agencies which are directly related to the enforcement of laws respecting narcotics and dangerous drugs. Each department and agency of<br />

the Federal Government shall, upon request and to the extent permitted by law, assist the Attorney General in the performance of functions<br />

assigned to him pursuant to this order, and the Attorney General may, in carrying out those functions, utilize the services of any other<br />

agencies, federal and state, as may be available and appropriate.<br />

Sec. 2. Executive Order No. 11641 of January 28, 1972, 1 is hereby revoked and the Attorney General shall provide for the reassignment<br />

of the functions of the Office for Drug Abuse Law Enforcement and for the abolishment of that Office.<br />

Sec. 3. Executive Order No. 11676 of July 27, 1972, 1 is hereby revoked and the Attorney General shall provide for the reassignment of the<br />

functions of the Office of Narcotics Intelligence and for the abolishment of that Office.<br />

Sec. 4. Section 1 of Executive Order No. 11708 of March 23, 1973, 2 as amended, placing certain positions in level IV of the Executive<br />

Schedule is hereby further amended by deleting—<br />

(1) “(6) Director, Office for Drug Abuse Law Enforcement,<br />

Department of Justice”; and<br />

(2) “(7) Director, Office of Narcotics Intelligence,<br />

Department of Justice.”<br />

Sec. 5. <strong>The</strong> Attorney General shall provide for the winding up of the affairs of the two offices and for the reassignment of their functions.<br />

Sec 6. <strong>This</strong> order shall be effective as of July 1, 1973.<br />

Richard Nixon<br />

THE WHITE HOUSE,<br />

July 6, 1973<br />

In 1973, President Richard Nixon declared “an all-out<br />

global war on the drug menace” and sent Reorganization<br />

Plan No. 2 to Congress. “Right now,” he pointed<br />

out, “the federal government is fighting the war on drug<br />

abuse under a distinct handicap, for its efforts are those<br />

of a loosely confederated alliance facing a resourceful,<br />

elusive, worldwide enemy. Certainly, the cold-blooded<br />

underworld networks that funnel narcotics from suppliers<br />

all over the world are no respecters of the bureaucratic<br />

dividing lines that now complicate our anti-drug<br />

efforts.”<br />

13<br />

In the spring and summer of 1973, the U.S. House of<br />

Representatives and the U.S. Senate heard months of<br />

testimony on President Nixon’s Reorganization Plan<br />

Number 2, which proposed the creation of a single federal<br />

agency to consolidate and coordinate the<br />

government’s drug control activities.<br />

At that time, the BNDD, within the Department of Justice,<br />

was responsible for enforcing the federal drug laws.<br />

However, the U.S. Customs Service and several other<br />

Justice entities (ODALE and the Office of National

Narcotics Intelligence) were also responsible for various aspects<br />

of federal drug law enforcement. Of great concern to the<br />

Administration and the Congress were the growing availability<br />

of drugs in most areas of the United States, the lack of<br />

coordination and the perceived lack of cooperation between<br />

the U.S. Customs Service and the BNDD, and the need for<br />

better intelligence collection on drug trafficking organizations.<br />

According to the final report from the Senate Committee on<br />

Government Operations issued on October 16, 1973, the benefits<br />

anticipated from the creation of the DEA included:<br />

1. Putting an end to the interagency rivalries that have undermined<br />

federal drug law enforcement, especially the rivalry<br />

between the BNDD and the U.S. Customs Service;<br />

2. Giving the FBI its first significant role in drug enforcement<br />

by requiring that the DEA draw on the FBI’s expertise in<br />

combatting organized crime’s role in the trafficking of illicit<br />

drugs;<br />

3. Providing a focal point for coordinating federal drug enforcement<br />

efforts with those of state and local authorities,<br />

as well as with foreign police forces;<br />

4. Placing a single Administrator in charge of federal drug law<br />

enforcement in order to make the new DEA more accountable<br />

than its component parts had ever been, thereby safeguarding<br />

against corruption and enforcement abuses;<br />

5. Consolidating drug enforcement operations in the DEA and<br />

establishing the Narcotics Division in Justice to maximize<br />

coordination between federal investigation and prosecution<br />

efforts and eliminate rivalries within each sphere; and<br />

6. Establishing the DEA as a superagency to provide the momentum<br />

needed to coordinate all federal efforts related to<br />

drug enforcement outside the Justice Department, especially<br />

the gathering of intelligence on international narcotics<br />

smuggling.<br />

14<br />

DEA<br />

John R. Bartels, Jr.<br />

DEA Administrator<br />

1973-1975<br />

On September 12, 1973, the White House selected John R.<br />

Bartels, Jr., a native of Brooklyn, New York, a former federal<br />

prosecutor, and Deputy Director of the ODALE, to be the<br />

DEA’s first Administrator. He was confirmed by the U.S. Senate<br />

on October 4, 1973. Prior to his employment with the<br />

ODALE and the DEA, Mr. Bartels had been an Assistant U.S.<br />

Attorney, Southern District of New York, from 1964-1968.<br />

From 1969-1971, he was an Adjunct Professor, Rutgers University<br />

School of Law. From 1972-1973, Mr. Bartels was the<br />

Chief of the Organized Crime Strike-Force, U.S. Department<br />

of Justice, Newark, New Jersey; Counsel to Governor Nelson<br />

Rockefeller; and Deputy Assistant Attorney General, U.S.<br />

Department of Justice, Criminal Division. He was later a<br />

delegate for the United Nations Commission on Narcotic<br />

Drugs in 1974. He currently resides in White Plains, New<br />

York.<br />

Early Developments in the DEA<br />

When John R. Bartels, Jr., was confirmed as the DEA’s first<br />

Administrator on October 4, 1973, he had two goals for the<br />

new agency: (1) to integrate narcotics agents and U.S. Customs<br />

agents into one effective force; and (2) to restore public<br />

confidence in narcotics law enforcement. From the very beginning,<br />

Mr. Bartels was faced with the unenviable task of<br />

unifying the efforts of several drug law enforcement entities.<br />

One of the most serious obstacles arose from conflicting philosophies<br />

of various agencies, particularly the BNDD and the<br />

U.S. Customs Service. To ease the process, U.S. Customs<br />

agents were placed in top positions throughout the DEA. For<br />

example, Fred Rody, Regional Director in Miami, became the<br />

DEA’s Deputy Administrator in December 1979; John Lund<br />

was appointed as Deputy Assistant Administrator; and John<br />

Fallon named as Regional Director in New York. Administrator<br />

Bartels issued specific instructions to federal narcotics<br />

agents: “<strong>This</strong> Statement of Policy outlines the measures taken<br />

by the Drug Enforcement Administration to prevent incidents<br />

which might infringe on individual rights or jeopardize the<br />

successful prosecution of a case. <strong>The</strong> guidelines require clearcut<br />

lines of command and control in enforcement situations<br />

and stress that operations must be carried out in a manner<br />

that is legally correct, morally sound, with full respect for the<br />

civil rights, human dignity of persons involved, and the sanctity<br />

of the home.” <strong>The</strong> guidelines also restricted vehicular<br />

arrests and prohibited participation in raids by non-law enforcement<br />

personnel.

Creation of the DEA Intelligence<br />

Program (1973)<br />

Intelligence had long been recognized as an essential element<br />

in the success of any investigative or law enforcement agency.<br />

Accurate and up-to-date information was required to assess<br />

the operations and vulnerabilities of criminal networks, to<br />

interdict drugs in a systematic way, to forecast new methods of<br />

trafficking, to evaluate the impact of previous activities, and to<br />

establish long-range drug strategies and policies. Included in<br />

the DEA mission was a mandate for drug intelligence. <strong>The</strong><br />

DEA’s Office of Intelligence came<br />

into being on July 1, 1973, upon implementation<br />

of Presidential<br />

Reorganization Plan No. 2. <strong>The</strong> Code<br />

of Federal Regulations charged the<br />

Administrator of the DEA with:<br />

<strong>The</strong> development and maintenance<br />

of a National Narcotics Intelligence<br />

system in cooperation with federal,<br />

state, and local officials, and the provision<br />

of narcotics intelligence to<br />

any federal, state, or local official that<br />

the Administrator determines has a<br />

legitimate official need to have access<br />

to such intelligence.<br />

To support this mission, specific functions<br />

were identified as follows:<br />

• Collect and produce intelli<br />

George M. Belk<br />

Assistant Administrator for Intelligence<br />

July 1973-July 31, 1975<br />

gence to support the Administrator<br />

and other federal, state, and local agencies;<br />

• Establish/maintain close working relationships with all<br />

agencies that produce or use drug intelligence;<br />

• Increase the efficiency in the reporting, analysis, storage,<br />

retrieval, and exchange of such information; and<br />

• Undertake a continuing review of the narcotics intelligence<br />

effort to identify and correct deficiencies.<br />

<strong>The</strong> DEA divided drug intelligence into three broad categories:<br />

tactical, operational, and strategic. Tactical intelligence provides<br />

immediate support to investigative efforts by identifying<br />

traffickers and movement of drugs. Operational intelligence<br />

provides analytical support to investigations and structuring<br />

organizations. Strategic intelligence focuses on developing a<br />

comprehensive and current picture of the entire system by<br />

which drugs are cultivated, produced, transported, smuggled,<br />

and distributed around the world. <strong>The</strong>se definitions<br />

remain valid in 1998.<br />

15<br />

To build upon its drug intelligence mandate in 1973, the<br />

DEA’s Intelligence Program consisted of two major<br />

elements: the Office of Intelligence at Headquarters and<br />

the Regional Intelligence Units (RIU) in domestic and<br />

foreign field offices. <strong>The</strong> structure of the Office of<br />

Intelligence was divided into five entities: International<br />

and Domestic Divisions, Strategic Intelligence Staff,<br />

Special Operations and Field Sup-<br />

port Staff, and the Intelligence<br />

Systems Staff. Its structure paralleled<br />

that of the Office of<br />

Enforcement.<br />

<strong>The</strong> RIUs had four objectives: (1)<br />

Provide a continuing flow of actionable<br />

intelligence to enhance the<br />

tactical effectiveness of regional<br />

enforcement efforts; (2) Support<br />

management planning of the overall<br />

regional enforcement program;<br />

(3) Contribute to interregional and<br />

strategic collection programs of the<br />

Office of Intelligence; and (4) Facilitate<br />

exchange of intelligence<br />

information with state and local law<br />

enforcement domestically and with<br />

host-country enforcement abroad.<br />

Initially, the Intelligence Program was staffed by DEA<br />

special agents, with very few professional intelligence<br />

analysts (I/As). In DEA’s first I/A class in 1974, there<br />

were only eleven I/As. However, during the last 30<br />

years, the Intelligence Program has grown significantly.<br />

From only a few I/As in the field and Headquarters in<br />

1973, the cadre of I/As now numbers 730.

<strong>The</strong> Unified Intelligence<br />

Division (UID) (1973)<br />

In October 1973, the DEA’s first field intelligence unit based<br />

on the task force concept was created. <strong>The</strong> unit, named the<br />

Unified Intelligence Division (UID), included DEA special<br />

agents, DEA intelligence analysts, New York State Police<br />

investigators, and New York City detectives. Along with its<br />

unique status as an intelligence task force, the UID was also<br />

one of the first field intelligence units to systematically<br />

engage all aspects of the intelligence process, specifically<br />

collection, evaluation, analysis, and dissemination. <strong>This</strong><br />

pioneering role expanded the horizons of drug law<br />

enforcement field intelligence units, which, at the time, were<br />

often limited to collecting information, maintaining dossiers,<br />

and providing limited case support. <strong>This</strong> proactive stance<br />

was immediately successful as UID was able to develop and<br />

disseminate extensive intelligence on traditional organized<br />

crime-related drug traffickers and identify not only the<br />

leaders, but also those who were likely to become leaders.<br />

UID also developed and disseminated intelligence throughout<br />

the federal, state, and local law enforcement community<br />

on the members, associates, and contacts of infamous heroin<br />

violator Leroy “Nicky” Barnes. Significant intelligence<br />

operations continued through the 1980s, with UID taking a<br />

leading role in providing intelligence on the crack cocaine<br />

epidemic and on Cali cocaine mafia operations in New York.<br />

<strong>The</strong> UID’s proactive intelligence task force concept<br />

continues to build upon successes of the past.<br />

Shortly after the creation of UID, the Drug Enforcement<br />

Coordinating System (DECS) was developed. DECS is a<br />

repository index system of all active drug cases in the New<br />

York metropolitan area. <strong>The</strong> DECS system connects<br />

agencies that have common investigative targets or common<br />

addresses that are part of their investigations. It was created<br />

to enhance officer safety and to promote greater cooperation<br />

and coordination among drug law enforcement agencies by<br />

preventing duplication of effort on overlapping investigations<br />

being conducted by member agencies. DECS, which<br />

began as a joint venture of DEA/NYSP/NYPD housed in the<br />

UID, now has a membership of 40 investigative units<br />

involved in drug law enforcement, and is the prototype for<br />

many similar systems that have since been developed across<br />

the country.<br />

DEA Intelligence Analyst<br />

DEA Intelligence Analyst Training School #1<br />

Training School #1<br />

(November 1974)<br />

SA Robert McCall SA Omar Aleman<br />

SA Thomas Shreeve SA Ron Garribotto<br />

SA Leonard Rzcpczynski SA Angelo Saladino<br />

SA Charles Henry IA Beverly Singleton<br />

SA John Hampe IA Ann Augusterfer<br />

SA Thomas Anderson IA Adrianne Darnaby<br />

SA Robert Janet IA Beverly Ager<br />

SA Christopher Bean IA Janet Gunther<br />

SA Michael Campbell IA Joan Philpott<br />

SA Donald Bramwell IA Wiliam Munson<br />

SA Murry Brown IA Brian Boyd<br />

SA Donald Stowell IA Joan Bannister<br />

SA Arthur Doll IA Jennifer Garcia-Tobar<br />

SA Frank Gulich IA Eileen Hayes<br />

SA Norman Noordweir<br />

SA Lynn Williams<br />

National Narcotics Intelligence<br />

System (NADDIS)<br />

In 1973, the DEA developed the National Narcotics Intelligence<br />

System (NADDIS), which became federal law<br />

enforcement’s first automated index. <strong>The</strong> creation of NADDIS<br />

was possible because the DEA was the first law enforcement<br />

agency in the nation to adopt an all-electronic, centralized,<br />

computer database for its records. NADDIS, composed of<br />

data from DEA investigative reports and teletypes, provided<br />

16<br />

agents in all DEA domestic offices with electronic access to<br />

investigative file data. NADDIS searches could be conducted<br />

NADDIS contained approximately 4.5 million records, with<br />

5,000 new records being added every week. NADDIS remains<br />

the largest and most frequently used of the 40 specialized<br />

information systems operated by the DEA.

Graduation of the First DEA<br />

Special Agents<br />

<strong>The</strong> first DEA Special Agent Basic Training Class (BA-1)<br />

graduated on November 16, 1973. Reverend James W.<br />

McMurtie, Principal of Bishop Denis J. O’Connell High School<br />

in Arlington, Virginia, gave the Invocation honoring the 40<br />

men and women of BA-1, and DEA Administrator Bartels gave<br />

the welcome and introductions. <strong>The</strong> Training Division chief<br />

was Paul F. Malherek, and the class counselors were Calvin C.<br />

Campbell of the Miami Regional Office, Allen L. Johnson of the<br />

New Orleans Regional Office, and Henry S. Lincoln of the San<br />

Diego District Office.<br />

BA-1 Graduates<br />

Ralph Arroyo<br />

Terry T. Baldwin<br />

Richard J. Barter<br />

Richard E. Bell<br />

Donald H. Bloch<br />

Henry J. Braud, Jr.<br />

Michael E. Byrnes<br />

James W. Castillo<br />

Andrew G. Cloke<br />

George L. Coleman<br />

Cruz Cordero, Jr.<br />

Salvadore M. Dijamco<br />

Clark S. Edwards<br />

John H. Felts<br />

Andrew G. Fenrich<br />

Carliese R. Gordon<br />

Annabelle Grimm<br />

Bernard Harry<br />

Richard Phillip Holmes<br />

Antonio L. Huertas<br />

Dennis F. Imamura<br />

James Jefferies, Jr.<br />

Richard C. Kazmar<br />

Anthony V. Lobosco<br />

Sherman A. Lucas III<br />

John W. Lugar, Jr.<br />

Edward C. Maher<br />

Charles E. Mathis<br />

Thomas L. Mones<br />

Donald E. Nelson<br />

Dennis A. O’Neil<br />

Juan R. Rodriguez<br />

Thomas J. Salvatore<br />

Edward J. Schlachter<br />

Arthur T. Tahuari<br />

Frank Torres, Jr.<br />

Mary A. Turner<br />

Robert Bruce Upchurch<br />

Adis J. Wells<br />

James Hiram Williams<br />

Joint Efforts with Mexico<br />

(1974)<br />

By 1972, the quantity of brown heroin from Mexico available<br />

in the United States had risen 40 percent higher than the<br />

quantity of white heroin from Europe. Traditional international<br />

border control was no longer effective against the problem,<br />

and in 1974, the Government of Mexico requested U.S.<br />

technical assistance. On January 26, 1974, Operation SEA/M<br />

(Special Enforcement Activity in Mexico) was launched in<br />

the State of Sinaloa to combat the opium and heroin traffic.<br />

One month later, a second joint task force, Operation Endrun,<br />

began operations in the State of Guerrero, concentrating on<br />

marijuana and heroin interdiction. Meanwhile, a third effort,<br />

Operation Trident, focused on controlling the traffic of illegally<br />

manufactured dangerous drugs produced in Mexico.<br />

Despite the fact that law enforcement in Mexico had some<br />

successes, these early efforts did not, in the long term, prevent<br />

the development of powerful drug trafficking organizations<br />

based in Mexico.<br />

17<br />

BA 2 graduate Michael Vigil accepts his certificate from<br />

William Dirken, Perry Rivkind, and Paul Malherek of DEA<br />

Training.<br />

Administrator John R. Bartels, flanked by two armed<br />

members of the Mexican Federal Judicial Police, made an<br />

on-the-spot inspection of the poppy eradication program<br />

during a 1974 visit to Mexico.

<strong>The</strong> Collapse of the DEA<br />

Miami Office Building (1974)<br />

<strong>The</strong> DEA was still a new agency when tragedy struck the<br />

Miami Field Division. On August 5, 1974, at 10:24 a.m., the<br />

roof of the Miami office came crashing down, killing seven<br />

and trapping others in a pile of twisted steel and concrete.<br />

Between 125 and 150 people worked in the building. Those<br />

who died included: Special Agent Nicholas Fragos; Mary<br />

Keehan, Secretary to the Acting Regional Director; Special<br />

Agent Charles Mann; Anna Y. Mounger, Secretary; Anna<br />

Pope, Fiscal Assistant; Martha D. Skeels, Supervisory Clerk-<br />

Typist; and Mary P. Sullivan, Clerk-Typist. Although the<br />

people who were in the building thought it was an explosion<br />

or an earthquake, officials initially theorized that the dozens<br />

of cars in the parking facility on the roof were too heavy for<br />

the six-inch-thick slab of concrete supporting them. Later, it<br />

was found that the resurfaced parking lot, coupled with salt in<br />

the sand, had eroded and weakened the supporting steel structure<br />

of the building. <strong>The</strong> section that collapsed contained a<br />

processing room and a laboratory. <strong>The</strong> building was erected<br />

in 1925, and in 1968 had undergone a full engineering inspection,<br />

at which time it was cleared to house DEA offices.<br />

El Paso Intelligence Center<br />

(1974)<br />

In 1973, with increasing drug activity along the Southwest<br />

Border, the BNDD found that information on drugs<br />

was being collected by the DEA, Customs, BNDD, FBI,<br />

and FAA, but was not being coordinated. <strong>The</strong> DEA and<br />

the INS were also collecting information on the smuggling<br />

of aliens and guns. In 1974, the Department of Justice<br />

submitted a report from that BNDD study entitled,<br />

“A Secure Border: An Analysis of Issues Affecting the<br />

U.S. Department of Justice” to the Office of Management<br />

and Budget that provided recommendations to im<br />

Drug Abuse Warning<br />

Network (1974)<br />

In 1974, the Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) was<br />

designed and developed by the scientific staff of the DEA’s<br />

Office of Science and Technology. DAWN was created to<br />

assist the federal government in identifying and evaluating<br />

the scope and extent of drug abuse in the United States. It<br />

was jointly funded with the National Institute of Drug Abuse.<br />

DAWN incorporated data from various sources of intelligence<br />

within the DEA and from such outside sources as fed<br />

18<br />

Rescue workers took injured victims from the Miami<br />

building.<br />

prove drug and border enforcement operations along the<br />

Southwest Border. One of the recommendations proposed<br />

the establishment of a regional intelligence center<br />

to collect and disseminate information relating to drug,<br />

illegal alien, and weapons smuggling to support field enforcement<br />

agencies throughout the country. As a result,<br />

in 1974, the El Paso Intelligence Center (EPIC) was<br />

established to provide tactical intelligence to federal,<br />

state, and local law enforcement agencies on a national<br />

scale. Staffed by representatives of the DEA and the<br />

INS, EPIC has since expanded into a national drug intelligence<br />

center supporting U.S. law enforcement entities<br />

that focus on worldwide drug smuggling.<br />

eral, state, and local law enforcement agencies, the pharmaceutical<br />

industry, and scientific literature. Over 1,300 different<br />

facilities supply data to the program.<br />

Beginning in the early 1970s, DAWN collected information<br />

on patients seeking hospital emergency treatment related to<br />

their use of an illegal drug or the nonmedical use of a legal<br />

drug. Data were collected by trained reporters (nurses and<br />

other hospital personnel) who reviewed medical charts. <strong>The</strong>y

monitored notations by the hospital personnel who treated<br />

the patients that drug use was the reason for the emergency<br />

visit.<br />

Hospitals participating in DAWN are non-federal, short-stay<br />

general hospitals that feature a 24-hour emergency department.<br />

Since 1988, the DAWN data was collected from a<br />

representative sample of these hospitals located throughout<br />

the United States, including 21 specific metropolitan areas.<br />

<strong>The</strong> data from this sample were used to generate estimates of<br />

the total number of emergency department drug episodes and<br />

drug mentions in all such hospitals.<br />

In 1972, Timothy Leary (center) was brought to justice by<br />

DEA Special Agents Don Strange (right) and Howard<br />

Safir (left). Leary, a psychology instructor, was fired from<br />

his post at Harvard University as a result of his<br />

experimentation with LSD. In 1969, he founded a<br />

clandestine drug-trafficking ring, known as the<br />

Brotherhood of Eternal Love, that became the largest<br />

supplier of hashish and LSD in the United States.<br />

19<br />

Narcotic Addict Treatment Act<br />

(1974)<br />

Public Law 93-281<br />

<strong>The</strong> Narcotic Addict Treatment Act was passed in 1974 and<br />

amended the Controlled Substances Act to provide for the<br />

separate registration of doctors and other practitioners who<br />

used narcotic drugs in the treatment of addicts. It also provided<br />

physicians who were treating narcotic addiction with specific<br />

guidelines and medications. <strong>This</strong> act eliminated the indiscriminate<br />

prescription of narcotics to addicts and reduced the<br />

diversion of pharmaceutical narcotics.<br />

A 1970 raid on a Washington, D.C., apartment by<br />

metropolitan police officers resulted in the seizure of<br />

LSD and marijuana, as well as the unusual antique<br />

chandelier pictured above. <strong>The</strong> light fixtures on the<br />

chandelier had been removed and replaced with rubber<br />

hose, creating a giant marijuana pipe.

Aviation Training<br />

In 1971, the BNDD launched its aviation program with<br />

one special agent/pilot, one airplane, and a budget of<br />

$58,000. <strong>The</strong> concept of an Air Wing was the brainchild<br />

of Marion Joseph, an experienced former United States<br />

Air Force pilot and a veteran special agent stationed in<br />

Atlanta, Georgia. Over the years, Special Agent Joseph<br />

had seen how the police used aircraft for surveillance,<br />

search and rescue, and<br />

the recapturing of fugitives. His<br />

analysis led him to conclude that<br />

a single plane “could do the<br />

work of five agents and five vehicles<br />

on the ground.”<br />

As drug trafficking increased<br />

nationwide, it became evident<br />

that it had no boundaries and<br />

that law enforcement needed<br />

aviation capabilities. Although<br />

Special Agent Joseph convinced<br />

his superiors of the merits<br />

of his idea, no funding was<br />

available. Management told<br />

Agent Joseph that if he could<br />

find an airplane, they would further<br />

consider the Air Wing concept.<br />

At this point, Special<br />

Agent Joseph approached the<br />

United States Air Force, and under the Bailment Property<br />

Transfer Program that allows the military to assist<br />

other government entities, he secured one airplane—a<br />

Vietnam war surplus Cessna Skymaster.<br />

<strong>The</strong> benefit of air support to drug law enforcement operations<br />

became immediately apparent, and the request<br />

for airplanes grew rapidly. By 1973, when the DEA was<br />

formally established, the Air Wing already had 41 special<br />

agent pilots operating 24 aircraft in several major<br />

cities across the United States. Most of these aircraft<br />

were fixed-wing, single-engine, piston airplanes that were<br />

primarily used for domestic surveillance.<br />

20<br />

<strong>The</strong> National Training Institute, the DEA’s first training<br />

program, was located at DEA headquarters, 1405 “Eye”<br />

Street in Washington, D.C. At that time, training was<br />

divided into three major divisions: special agent training,<br />

police training, and international training.<br />

Training was carried out in a three-story bank building<br />

adjacent to DEA headquarters that had been converted<br />

for training purposes. <strong>The</strong> building had a gymnasium<br />

located on the first floor, lockers and showers in the<br />

basement, and a 5-point firing range on the second floor.<br />

Special agent trainees were housed in hotels within<br />

walking distance of DEA headquarters.<br />

In the absence of the realistic “Hogan’s Alley,” a lifesized,<br />

simulated neighborhood of today, training practicals<br />

were conducted on public streets. <strong>The</strong> DEA had leased<br />

a 20-acre farm near Dulles Airport in rural Virginia, as<br />

well as a house in Oxen Hill, Maryland, to practice raids<br />

and field exercises. Basic Agent training lasted 10<br />

weeks, and the Training Institute supported three classes,<br />

with 53 students per class, in session at all times. Graduations<br />

occurred every three weeks. Coordinators were<br />

from the headquarters staff, and counselors were brought<br />

in from the field for temporary training duty. In addition<br />

to training basic agents, the DEA also offered training<br />

programs for compliance investigators, intelligence analysts,<br />

chemists, supervisors, mid-level managers, executives,<br />

technical personnel, state and local police officers,<br />

and international law enforcement personnel.<br />

Trainee John Wilder

Technology<br />

Over the years, the combination of tech<br />

1975: After seized drugs were used as<br />

nology and law enforcement have solved evidence, they were burned by DEA<br />

some of the biggest criminal cases in the evidence technicians using special ovens<br />

world. However, by 1998, the DEA’s tech- in the presence of responsible witnesses.<br />

nology ranked among the most sophisticated.<br />

That was not always the case.<br />

During the DEA’s formative years, technical<br />

investigative equipment was limited<br />

both in supply and technical capabilities.<br />

In 1971, the entire budget for investigative<br />

technology was less than $1 million.<br />

<strong>This</strong> budget was used to buy radio and<br />

investigative equipment and to fund the<br />

teletype system.<br />

Video surveillance was rare because of cause as was required for a Title III<br />

the size and expense of camera equip- Wire Intercept.<br />

ment. Cameras were tube type, required<br />

special lighting, and could not be concealed. Early video<br />

tape recorders were extremely expensive and were reelto-reel<br />

or the very early version of cassettes called U-<br />

Matic.<br />

Pen registers, or dialed number recorders, were more<br />

advanced than the older versions, which actually punched<br />

holes in a tape, similar to an old ticker tape, in response<br />

to the pulses from a rotary dialed phone. Pen registers<br />

were also limited because federal law at the time required<br />

the same degree of probable<br />

21<br />

Title IIIs were conducted with reel-to-reel tape recorders.<br />

However, the DEA did not conduct many Title<br />

IIIs because they were labor intensive, and the agency<br />

seldom had sufficient personnel to work the intercepts.<br />

In 1973, body-worn recorders used by agents during<br />

investigations had advanced from large belt packs to<br />

smaller versions. However, reliability was always a concern.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se old belt types, called KELsets, consisted<br />

of a transmitter and a belt of batteries worn by the undercover<br />

agent. Unfortunately, the belt was not easily<br />

concealable, and the batteries would occasionally overheat<br />

and burn the backs of the agents.<br />

When the BNDD was formed it did not have a radio<br />

system, but in 1971, the agency began installing a nationwide<br />

UHF radio system for operations. (<strong>The</strong> DEA’s<br />

radio system was installed in 1973.) When an early facsimile<br />

machine was installed in 1972, it took six minutes<br />

to transmit one page, and pages often had to<br />

be re-sent due to communication failures. No<br />

paging equipment was available because<br />

dedicated frequencies had to be used for<br />

each pager. Only doctors and a few<br />

select individuals could obtain pagers.<br />

Although cellular phones did not exist,<br />

there was a mobile telephone service.<br />

However, only the DEAAdministrator had<br />

a mobile phone, and the service was slow<br />

and unreliable.

Laboratories<br />

One of the essential functions carried out by the DEA and its<br />

predecessor agencies was providing laboratory support. <strong>The</strong><br />

success of cases made against major drug traffickers depended<br />

in part upon analysis of the drug evidence gathered<br />

during narcotics investigations. <strong>The</strong> DEA’s laboratory system,<br />

one of the finest in the world, has roots in the DEA’s<br />

predecessor agencies. Although the two predecessor agencies,<br />

BDAC and FBN, did not have laboratories under their<br />

direct supervision, lab support was available within their respective<br />

departments. Ultimately, the DEA’s laboratory system<br />

began to take shape through the consolidation and transfer<br />

of several lab programs within the U.S. Government. <strong>The</strong><br />

first laboratory personnel transferred to the BNDD came from<br />

the Food and Drug Administration‘s (FDA) Division of Pharmaceutical<br />

Chemistry and Microanalytical Group in Washington,<br />

D.C. <strong>The</strong>y were primarily responsible for performing<br />

the ballistics analyses of tablets and capsules, identifying<br />

newly-encountered compounds found in drug traffic, and<br />

conducting methods development. According to the agreement<br />

with the FDA, the new agency would take control of<br />

one of the FDA labs. In August 1968, six chemists formed<br />

what eventually became the Special Testing and Research<br />

Laboratory. <strong>The</strong> first of the five regional DEA laboratories<br />

was the Chicago Regional Laboratory that opened in December<br />

1968. <strong>The</strong> New York, Washington, Dallas, and San Francisco<br />

Regional Laboratories were formed in April 1969. <strong>The</strong><br />

original chemist work force for these laboratories came from<br />

several field laboratories run by government agencies. <strong>The</strong><br />

professional staffing of the six laboratories consisted of 36<br />

“bench” chemists doing physical lab research, supplemented<br />

by five supervisory chemists. In 1970, the first full year of<br />

operation, the laboratories analyzed almost 20,000 drug exhibits.<br />

During the next two years, the laboratories’ work load<br />

increased by 46 percent and 19 percent, respectively. To<br />

meet the increased work load demand, staffing more than<br />

doubled to 94 by 1972 (including laboratory and BNDD headquarters<br />

management personnel.) In 1971, both the Washington<br />

and Dallas Regional Laboratories moved to larger facilities,<br />

and in January 1972, the BNDD opened its sixth regional<br />

laboratory in Miami. After the DEA was created, a<br />

seventh field laboratory was opened in San Diego in August<br />

1974.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Original DEA Forensic Chemists<br />

Headquarters<br />

Frederick Garfield, John Gunn, Richard Frank, and William Butler.<br />

Special Testing and Research Laboratory<br />

Director Stanley Sobol, Albert Tilson, Joseph C. Koles, Victor A.<br />

Folen, Robert Ferrera, Francis B. Holmes, and Albert Sperling.<br />

Chicago Regional Laboratory<br />

Director Jerry Nelson, Roger B. Fuelster, Ferris H. Van, David W.<br />

Parmalee, Nora L. Williams, Lawrence O. Buer, Dennis E. Korte, and<br />

James P. Done.<br />

22<br />

Creation of the Federal Drug<br />

Laboratory System<br />

DEA forensic<br />

chemist Dr. Albert<br />

Tillson is shown<br />

analyzing an<br />

illegal drug.<br />

<strong>The</strong> analysis of seized drugs<br />

performed by DEA forensic<br />

chemists provides evidence that<br />

is often essential for the<br />

successful prosecution and<br />

conviction of drug traffickers.<br />

New York Regional Laboratory<br />

Director Anthony Romano, Elinor R. Swide, Robert Bianchi, Roger F.<br />

Canaff, and Paul DeZan.<br />

Washington DC Regional Laboratory<br />

Director Jack Rosenstein, Richard Moore, Thaddeus E. Tomczak,<br />

Richard Fox, and Benjamin A. Perillo.<br />

Dallas Regional Laboratory<br />

Director Jim Kluckhohn, Buddy R. Goldston, Charles B. Teer, John D.<br />

Wittwer, Richard Ruybal, and Michael D. Miller.<br />

San Francisco Regional Laboratory<br />

Director Robert Sager, Robert Countryman, Claude G. Roe, James<br />

Look, James A. Heagy, and John D. Kirk.

Killed in the Line of Duty<br />

Hector Jordan<br />

Died on October 14, 1970<br />

Working as a Supervisory Special Agent with<br />

the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous<br />

Drugs, Special Agent Jordan died in Chicago<br />

in an unprovoked attack by a roving gang.<br />

Gene A. Clifton<br />

Died on November 19, 1971<br />

Palo Alto, California Police Officer Clifton<br />

died from injuries received during a joint<br />

operation with the Bureau of Narcotics and<br />

Dangerous Drugs.<br />

Frank Tummillo<br />

Died on October 12, 1972<br />

Working in the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous<br />

Drugs, Special Agent Tummillo was<br />

killed during an undercover operation in<br />

New York City.<br />

George F. White<br />

Died on March 25, 1973<br />

Special Agent Pilot White of the Bureau of<br />

Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs was<br />

killed when his plane hit a power line near<br />

Tucson, Arizona.<br />

Richard Heath, Jr.<br />

Died on April 1, 1973<br />

Special Agent Heath of the Bureau of Narcotics<br />

and Dangerous Drugs died in Quito,<br />

Ecuador, from a gunshot wound received<br />

during an undercover operation in Aruba,<br />

Netherlands Antilles.<br />

Emir Benitez<br />

Died on August 9, 1973<br />

DEA Special Agent Benitez died from a gunshot<br />

wound he received during an undercover<br />

cocaine investigation in Fort Lauderdale,<br />

Florida.<br />

Gerald Sawyer<br />

Died on November 6, 1973<br />

Detective Sawyer of the Los Angeles, California<br />

Police Department, was killed while<br />

working in a joint undercover investigation<br />

with the DEA.<br />

Leslie S. Grosso<br />

Died on May 21, 1974<br />

Investigator Grosso of the New York State<br />

Police was shot during an undercover operation<br />

in New York City. He was assigned<br />

to the DEA’s New York City Joint Task Force.<br />

23<br />

Nickolas Fragos<br />

Died on August 5, 1974<br />

DEA Special Agent Fragos was killed on<br />

his first day of work as a DEA Special<br />

Agent. He died as a result of the collapse<br />

of the Miami Regional Office Building.<br />

Mary M. Keehan<br />

Died on August 5, 1974<br />

Ms. Keehan, secretary to the Acting Regional<br />

Director of the DEA’s Miami Regional Office,<br />

died as a result of the collapse of the<br />

Miami Regional Office building.<br />

Charles H. Mann<br />

Died on August 5, 1974<br />

DEA Special Agent Mann was killed on his<br />

first day of work after returning from an overseas<br />

assignment. He died as a result of<br />