Download - Royal Australian Navy

Download - Royal Australian Navy

Download - Royal Australian Navy

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

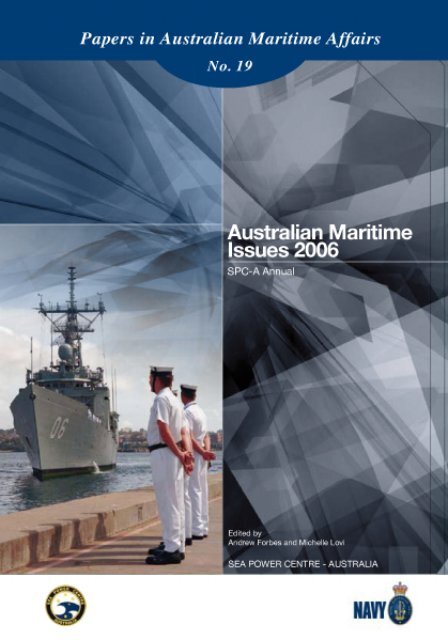

AUSTRALIAN<br />

MARITIME<br />

ISSUES 2006<br />

SPC-A ANNUAL

© Copyright Commonwealth of Australia 2007<br />

This work is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of study, research,<br />

criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, and with standard source<br />

credit included, no part may be reproduced without written permission. Inquiries should<br />

be addressed to the Director, Sea Power Centre - Australia, Department of Defence,<br />

CANBERRA ACT 2600.<br />

National Library of <strong>Australian</strong> Cataloguing-in-Publication entry<br />

Forbes, Andrew 1962-<br />

Lovi, Michelle 1976-<br />

<strong>Australian</strong> Maritime Issues 2006 – SPC-A Annual<br />

ISSN 1327-5658<br />

ISBN 0 642 29644 8<br />

1. <strong>Australian</strong> Department of Defence. 2. 3.<br />

I. Sea Power Centre - Australia. II. Title. (Series: Papers in <strong>Australian</strong> Maritime Affairs;<br />

No. 19.)<br />

363.70994

AUSTRALIAN<br />

MARITIME<br />

ISSUES 2006<br />

SPC-A ANNUAL<br />

Edited by<br />

Andrew Forbes and Michelle Lovi<br />

Sea Power Centre – Australia

iv<br />

Disclaimer<br />

The views expressed are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect the official policy<br />

or position of the Government of Australia, the Department of Defence and the <strong>Royal</strong><br />

<strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Navy</strong>. The Commonwealth of Australia will not be legally responsible in<br />

contract, tort or otherwise for any statement made in this publication.<br />

Sea Power Centre - Australia<br />

The Sea Power Centre - Australia (SPC-A), was established to undertake activities<br />

which would promote the study, discussion and awareness of maritime issues and<br />

strategy within the RAN and the Defence and civil communities at large. The mission<br />

of the SPC-A is:<br />

• to promote understanding of sea power and its application to the security of<br />

Australia’s national interests<br />

• to manage the development of RAN doctrine and facilitate its incorporation into<br />

ADF joint doctrine<br />

• to contribute to regional engagement<br />

• within the higher Defence organisation, contribute to the development of maritime<br />

strategic concepts and strategic and operational level doctrine, and facilitate<br />

informed force structure decisions<br />

• to preserve, develop, and promote <strong>Australian</strong> naval history.<br />

Comment on this Paper or any inquiry related to the activities of the Sea Power Centre -<br />

Australia should be directed to:<br />

Director Sea Power Centre - Australia<br />

Department of Defence Telephone: +61 2 6127 6512<br />

Canberra ACT 2600 Facsimile: +61 2 6127 6519<br />

Australia Email: seapower.centre@defence.gov.au<br />

Internet: www.navy.gov.au/spc

Papers in <strong>Australian</strong> Maritime Affairs<br />

The Papers in <strong>Australian</strong> Maritime Affairs series is a vehicle for the distribution of<br />

substantial work by members of the <strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Navy</strong> as well as members of the<br />

<strong>Australian</strong> and international community undertaking original research into regional<br />

maritime issues. The series is designed to foster debate and discussion on maritime<br />

issues of relevance to the <strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Navy</strong>, the <strong>Australian</strong> Defence Force, Australia<br />

and the region more generally.<br />

Other volumes in the series are:<br />

No. 1 From Empire Defence to the Long Haul: Post-war Defence Policy and its<br />

Impact on Naval Force Structure Planning 1945–1955 by Hector Donohue<br />

No. 2 No Easy Answers: The Development of the Navies of India, Pakistan,<br />

Bangladesh and Sri Lanka 1945–1996 by James Goldrick<br />

No. 3 Coastal Shipping: The Vital Link by Mary Ganter<br />

No. 4 <strong>Australian</strong> Carrier Decisions: The Decisions to Procure HMA Ships<br />

Albatross, Sydney and Melbourne by Anthony Wright<br />

No. 5 Issues in Regional Maritime Strategy: Papers by Foreign Visiting Military<br />

Fellows with the <strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Navy</strong> Maritime Studies Program — 1998<br />

edited by David Wilson<br />

No. 6 Australia’s Naval Inheritance: Imperial Maritime Strategy and the Australia<br />

Station 1880–1909 by Nicholas A. Lambert<br />

No. 7 Maritime Aviation: Prospects for the 21st Century edited by David Stevens<br />

No. 8 Maritime War in the 21st Century: The Medium and Small <strong>Navy</strong> Perspective<br />

edited by David Wilson<br />

No. 9 HMAS Sydney II: The Cruiser and the Controversy in the Archives of the<br />

United Kingdom edited by Captain Peter Hore, RN<br />

No. 10 The Strategic Importance of Seaborne Trade and Shipping: A Common<br />

Interest of Asia Pacific edited by Andrew Forbes<br />

No. 11 Protecting Maritime Resources: Boundary Delimitation, Resource Conflicts<br />

and Constabulary Responsibilities edited by Barry Snushall and Rachael<br />

Heath<br />

No. 12 <strong>Australian</strong> Maritime Issues 2004: SPC-A Annual edited by Glenn Kerr<br />

No. 13 Future Environmental Policy Trends to 2020 by the Centre for Maritime<br />

Policy, University of Wollongong, edited by Glenn Kerr and Barry Snushall

vi<br />

No. 14 Peter Mitchell Essays 2003 edited by Glenn Kerr<br />

No. 15 A Critical Vulnerability: The Impact of the Submarine Threat on Australia’s<br />

Maritime Defence 1915–1954 by David Stevens<br />

No. 16 <strong>Australian</strong> Maritime Issues 2005: SPC-A Annual edited by Gregory P. Gilbert<br />

and Robert J. Davitt<br />

No. 17 <strong>Australian</strong> Naval Personalities edited by Gregory P. Gilbert<br />

No. 18 ADF Training in Australia’s Maritime Environment edited by Chris Rahman<br />

and Robert J. Davitt<br />

No. 19 <strong>Australian</strong> Maritime Issues 2006: SPC-A Annual edited by Andrew Forbes<br />

and Michelle Lovi

vii<br />

Foreword<br />

I am pleased to introduce the Sea Power Centre – Australia (SPC-A) <strong>Australian</strong> Maritime<br />

Issues 2006: SPC-A Annual. SPC-A is charged with furthering the understanding<br />

of Australia’s broader geographic and strategic situation as an island continent in<br />

maritime Asia, and the role of maritime forces in protecting national interests that<br />

result from our geography.<br />

The 2006 Annual is an important contribution to the maritime debate in Australia and<br />

includes papers written on naval and maritime issues over the period July 2005 to<br />

December 2006. The majority of papers come from our monthly Semaphore newsletters,<br />

which covered issues ranging from historical pieces on aspects of RAN operations to<br />

issues associated with activities in the Southern Ocean, maritime security regulation<br />

and naval cooperation.<br />

Last November, Dr Stanley Weeks of Science Applications International Corporation was<br />

the 2006 Synnot Lecturer, and his two presentations on ‘The 1000-Ship <strong>Navy</strong> Concept’<br />

and ‘The Transformation of Naval Forces’ are included in the Annual as papers.<br />

The Annual also includes the 1959 and 1967 versions of the Radford-Collins Agreement,<br />

which were recently declassified. This agreement is the cornerstone of USN-RAN<br />

cooperation, and while oft referred to, has never been published in full until now.<br />

The SPC-A, on behalf of the Chief of <strong>Navy</strong>, conducts the annual Peter Mitchell Essay<br />

Competition, which is open to all members of Commonwealth navies with the rank of<br />

Commander or below. The winning essays for 2004, 2005 and 2006 are published at<br />

the end of this volume.<br />

Other significant publications of the SPC-A over the past 18 months include the RAN<br />

Reading List, <strong>Australian</strong> Naval Personalities, and as commercial publications, Australia’s<br />

<strong>Navy</strong> in the Gulf and Positioning Navies for the Future.<br />

I trust that you will find <strong>Australian</strong> Maritime Issues 2006: SPC-A Annual informative,<br />

interesting and a valuable contribution to the maritime and naval debate in<br />

Australia.<br />

Captain Peter J. Leavy, RAN<br />

Director<br />

Sea Power Centre - Australia<br />

26 March 2007

viii<br />

AUSTRALIAN MARITIME ISSUES 2006: SPC-A ANNUAL

ix<br />

Editors’ Note<br />

Semaphore issue 1 of 2006 has been omitted from this publication. The first issue of<br />

Semaphore published each year is used to promote the Sea Power Centre – Australia’s<br />

publications, conferences and other activities coordinated by the Centre. Issue 5 on<br />

the Western Pacific Naval Symposium was withdrawn, revised and published as<br />

issue 14.<br />

All information contained in this volume was correct at the time of publication or, in<br />

the case of papers being republished, was correct at the time of initial publication.<br />

Some information, particularly related to operations in progress, may not be current.<br />

However, information on the Armidale class patrol boats has been updated, as has the<br />

Western Pacific Naval Symposium membership. All views presented in this publication<br />

are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Commonwealth of<br />

Australia, the Department of Defence or the <strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Navy</strong>.<br />

Images included throughout this publication belong to the Department of Defence,<br />

unless otherwise indicated in the footnotes of each paper. We thank the following for<br />

providing additional images: Dr Gregory P. Gilbert (SPC-A), Mr Andrew Mackinnon<br />

(NHQ), and Mr John Perryman (SPC-A).<br />

We gratefully acknowledge the efforts of the staff in the Directorate of Classified<br />

Archival Records Review in the Department of Defence for the timely declassification<br />

of the Radford–Collins Agreement, which allowed those documents to be published<br />

here for the first time.

AUSTRALIAN MARITIME ISSUES 2006: SPC-A ANNUAL

xi<br />

Contributors<br />

Lieutenant Commander Phillip Anderson, OAM, RAN<br />

Lieutenant Commander Anderson is a conductor, composer and arranger and has been<br />

the Director of Music since July 2002. In 2004 he was awarded the Medal of the Order<br />

of Australia. As well as being admitted as a Fellow at Trinity College London, he is also<br />

a Graduate of the <strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Navy</strong> Staff College, and a Graduate of the Queensland<br />

University of Technology with a Master in Business Administration.<br />

Lieutenant Andrea Argirides, RANR<br />

Lieutenant Andrea Argirides has a Masters in Defence Studies from the <strong>Australian</strong><br />

Defence Force Academy (Canberra), and is currently completing Postgraduate<br />

Studies in Classics and Archaeology, University of Melbourne. Since joining the <strong>Royal</strong><br />

<strong>Australian</strong> Naval Reserve as a Naval Intelligence Officer, she completed a number of<br />

postings, including an 18-month appointment at Government House, Canberra, as the<br />

<strong>Navy</strong> Aide-de-Camp to the Governor-General. In July 2005, she joined the Sea Power<br />

Centre – Australia as the Senior Research Officer and then as Staff Officer Maritime<br />

Doctrine Development until December 2006.<br />

Chief Petty Officer Bob Brimson<br />

CPOWTR Bob Brimson served full time in the RAN from 1969 to 1989 and has been an<br />

active reservist since 1990. Some of his career highlights include Captain’s Secretary<br />

and Commissioning Crew HMAS Adelaide, and Defence Force Recruiting Centre,<br />

Melbourne. In a reserve capacity on Continuous Full Time Service, he served as<br />

Personnel Officer in HMAS Harman in 2002-03. During the period May to September<br />

2006 while undertaking reserve service at the Anzac Systems Program Office in<br />

Rockingham, he wrote his essay for the Peter Mitchell Essay Competition.<br />

Lieutenant Commander Penny Campbell, RAN<br />

Lieutenant Commander Penny Campbell joined the <strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Navy</strong> Reserves in<br />

1994 as an Intelligence Officer, and transferred to the Permanent <strong>Navy</strong> Force in 1996<br />

on completion of her legal studies. In 1999, she deployed briefly to East Timor, and<br />

later deployed to the Arabian Gulf as the legal adviser to Commander RAN Task Group<br />

633.1, during Operations SLIPPER and FALCONER. She served with Headquarters<br />

Integrated Area Defence Systems in Butterworth, Malaysia. She is currently Deputy<br />

Command Legal Officer in <strong>Navy</strong> Systems Command. She holds a Bachelor of Arts, a<br />

Bachelor of Law, a Masters of Law, a Masters of Arts (Maritime Policy) and is currently<br />

studying a Masters of Applied Linguistics.

xii<br />

AUSTRALIAN MARITIME ISSUES 2006: SPC-A ANNUAL<br />

Mr Andrew Forbes<br />

Mr Andrew Forbes is the Deputy Director Research in the Sea Power Centre - Australia,<br />

where he is responsible for the research and publication programs. He is a Visiting<br />

Senior Fellow at the <strong>Australian</strong> National Centre for Oceans Research and Security at<br />

the University of Wollongong, and a Research Fellow at the Centre for Foreign Policy<br />

Studies, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada.<br />

Lieutenant Commander Meg Ford, RAN<br />

Lieutenant Commander Ford joined the RAN as a nursing officer in 1994 and has been<br />

posted to HMAS Penguin, HMAS Coonawarra and held staff officer positions in <strong>Navy</strong><br />

Health and Health Capability Development in Canberra. She was involved in early<br />

planning for the Primary Casualty Reception Facilities and has been operationally<br />

deployed for Operations SHEPHERD, BEL ISI, TREK and RELEX. She holds a Masters<br />

Degree in Tropical Health (UQ), and is a midwife with specialty qualifications in<br />

Infection Control and Womens’ Health. She graduated from the <strong>Australian</strong> Command<br />

and Staff Course in 1996 and is currently the Executive Officer of Greater Sydney and<br />

Northern New South Wales Area Health Service.<br />

Dr Gregory P. Gilbert<br />

Dr Gregory Gilbert previously worked within the Department of Defence (<strong>Navy</strong>) from<br />

1985 to 1996 as a naval designer, and subsequently as a Defence contractor. He has<br />

broad research interests including: the archaeology and anthropology of warfare;<br />

Egyptology; international relations — the Middle East; maritime strategy and naval<br />

history. His excavations include Helwan, Hierakonpolis, Koptos and Sais in Egypt. He<br />

is currently the Senior Research Officer in the Sea Power Centre – Australia.<br />

Dr Andrew Gordon<br />

Dr Andrew Gordon holds a degree in International Politics from the University of<br />

Wales and a PhD in War Studies from the University of London (King’s College). He<br />

was a desk officer in the Conservative Party’s research department, then worked<br />

on official histories as a member of the Cabinet Office Historical Section. In 1997<br />

he joined the UK Joint Services Command and Staff College, where he has been a<br />

Reader in Defence Studies since 2001.<br />

Lieutenant Commander Mark Hammond, RAN<br />

Lieutenant Commander Mark Hammond is a submariner with sea experience in <strong>Royal</strong><br />

<strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Navy</strong> Oberon and Collins class submarines, United States <strong>Navy</strong> Los Angeles<br />

class, <strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Navy</strong> ‘S’ class, French <strong>Navy</strong> Amethyst class and Dutch <strong>Navy</strong> Walrus class<br />

submarines. He has completed the <strong>Royal</strong> Netherlands <strong>Navy</strong> Submarine Command<br />

Course, the RAN’s Principal Warfare Officer Course and the <strong>Australian</strong> Command

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

xiii<br />

and Staff Course. He was promoted to commander and is currently the Commanding<br />

Officer of the Collins class submarine HMAS Farncomb.<br />

Commander Wesley Heron, RANR<br />

Commander Wesley Heron retired from the RAN in January 2007 having completed<br />

26 years service. A seaman specialist, he saw active service in the Persian Gulf and<br />

completed sea service in major combatants, submarines and patrol boats. After a<br />

successful command of HMAS Wollongong, he was promoted to commander. His last<br />

posting was as Deputy Director Patrol and Hydrographic in the Capability Development<br />

Group, where he was project sponsor for seven major projects, including the Armidale<br />

class patrol boat project. He is currently employed as a Deputy Executive Director in<br />

the Infrastructure Projects Division of the Victorian Public Service.<br />

Lieutenant Commander Rebecca Jeffcoat, RAN<br />

Lieutenant Commander Rebecca Jeffcoat entered the <strong>Australian</strong> Defence Force Academy<br />

as a midshipman in 1990, and graduated with a Bachelor of Science (Oceanography)<br />

degree in 1992. In 1996 she studied for a Graduate Diploma in Meteorology with the<br />

Bureau of Meteorology, culminating in the award of the METOC sub-specialisation<br />

at HMAS Albatross. In 1997 she deployed within the fleet as a member of the Mobile<br />

METOC Team to Antarctica and to Heard and Mcdonald Islands in the Southern Ocean.<br />

She was Staff Officer <strong>Navy</strong> International Relations, NHQ, in 2004, and is currently<br />

the principal staff officer to the Deputy Chief of <strong>Navy</strong>.<br />

Mr Peter Laurence<br />

Mr Peter Laurence joined the Department of Defence in 2005 through the Graduate<br />

Development Program. Prior to this, he completed honours degrees in law and history<br />

at the University of Sydney. Although currently working in the Finance Executive, he<br />

maintains his passion for history by reading and finding artefacts for his small World<br />

War II collection.<br />

Mr Andrew Mackinnon<br />

Mr Andrew Mackinnon joined the <strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Australian</strong> Naval College as a junior entry<br />

in 1963, graduating in 1966, and from the <strong>Royal</strong> Naval College at Dartmouth, UK, in<br />

1968. He spent much of his early seagoing career in the Far East, including HMAS<br />

Vendetta off Vietnam in 1969-70; navigating officer of HMAS Torrens; and a brief tour<br />

in HMAS Hobart undergoing modernisation in San Francisco. He took command of<br />

HMAS Coonawarra in Darwin in 1995-96, for which he was awarded the Conspicuous<br />

Service Cross. After more than 38 years naval service, he retired from the RAN in 2001,<br />

immediately taking up a civilian position as Director <strong>Navy</strong> Strategic Analysis (now<br />

<strong>Navy</strong> Basing & Environmental Policy) in <strong>Navy</strong> Headquarters. He holds a Bachelor of<br />

Arts degree from Deakin University and a Graduate Diploma in Strategic Studies.

xiv<br />

AUSTRALIAN MARITIME ISSUES 2006: SPC-A ANNUAL<br />

Commodore Jack McCaffrie, AM, CSM, RANR<br />

Commodore Jack McCaffrie is the Visiting Naval Fellow at the Sea Power Centre -<br />

Australia. As an aviator, most of his flying career was spent in Grumman Trackers,<br />

embarked and ashore. Most of his later career was spent in a succession of jobs in<br />

Canberra. He retired early in 2003 on return from his final posting as Naval Attaché,<br />

Washington. Also a visiting fellow and part-time doctoral student at the Centre for<br />

Maritime Policy, University of Wollongong, he has published several articles and<br />

edited monographs on maritime strategy and naval history.<br />

Commander Andrew McCrindell, RAN<br />

Commander Andrew McCrindell graduated from Brunel University in 1985 and joined<br />

the <strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Navy</strong> in 1986 as an instructor specialist. He graduated from the <strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Navy</strong>’s<br />

course in Meteorology and Oceanography in 1989 and became a METOC specialist.<br />

ndrew immigrated to Australia in 1994 where he joined the <strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Navy</strong> as<br />

a METOC specialist. In 2003 he simultaneously completed the <strong>Australian</strong> Command<br />

and Staff Course and a Masters of Management in Defence Studies at the University<br />

of Canberra. Promoted to commander in January 2004, he is currently Director of<br />

the Directorate of Oceanography and Meteorology.<br />

Commander Jonathan Mead, AM, RAN<br />

Commander Jonathan Mead is a Principal Warfare Officer specialising in antisubmarine<br />

warfare, and a mine clearance diving officer. His previous service includes<br />

time in the patrol boats Bunbury and Geraldton; the destroyer escort Stuart; Sail<br />

Training Ship Young Endeavour; Executive Officer of Clearance Diving Team One;<br />

Training Ship Jervis Bay; frigates Canberra, Melbourne and Arunta; destroyer Brisbane;<br />

Executive Officer of Arunta; and Commanding Officer of HMAS Parramatta. He has<br />

had staff appointments at Maritime Headquarters as part of Sea Training Group, and<br />

as Staff Officer to the Chief of <strong>Navy</strong>. He holds a Diploma of Applied Science, a Masters<br />

in Management, is a graduate of the <strong>Australian</strong> Command and Staff Course, and has<br />

a PhD in International Relations. He is currently a student at the Indian National<br />

Defence University and will be Australia’s Defence Attache to India in 2008.<br />

Captain Richard Menhinick, CSC, RAN<br />

Captain Richard Menhinick joined the <strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Australian</strong> Naval College at Jervis Bay<br />

in January 1976. In 1987 he undertook the Principal Warfare Officer course and then<br />

served on exchange at sea in the <strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Navy</strong>. He served at sea in the 1990-91 Gulf War,<br />

for which he was awarded the Commendation for Distinguished Service. Later he was<br />

Deputy Director Surface Warfare Development in Capability Development Group, for<br />

which he was conferred the Conspicuous Service Cross. He has commanded HMA Ships<br />

Warramunga and Anzac, and was the Director of the Sea Power Centre - Australia. He

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

xv<br />

was promoted to commodore in December 2006 and is currently the Director General<br />

Strategic Plans in <strong>Australian</strong> Defence Headquarters. He holds a Bachelor of Arts and<br />

a Master of Maritime Studies.<br />

Mr Brett Mitchell<br />

Mr Brett Mitchell joined the Department of Defence in February 1988 and worked<br />

for the Naval Personnel Division before joining the Naval History Section as a Naval<br />

Historical Officer in 1992. Having read widely on RAN history, he has helped author<br />

numerous <strong>Navy</strong> historical publications, where he has collated and verified the accuracy<br />

of historical data. Brett has also provided research support to numerous naval veterans,<br />

Commonwealth agencies and other organisations. Currently he is writing operational<br />

histories for each decommissioned Fremantle class patrol boat.<br />

Commander Shane Moore, CSM, RAN<br />

Commander Shane Moore joined the <strong>Navy</strong> as a direct entry instructor lieutenant in<br />

1982. He has served at HMAS Nirimba, and on the Directing Staff at RAAF Staff College.<br />

He joined HMAS Creswell as a lecturer in Naval History and Warfare in 1986-87. In<br />

2002 Commander Moore joined HMAS Newcastle as the Task Group N2 for Operation<br />

SLIPPER in the Persian Gulf. On promotion to commander, he was selected as the first<br />

Director of the Naval Heritage Collection. He holds degrees from Macquarie and Sydney<br />

Universities in classics, history, archaeology and conservation as well as a Diploma<br />

in Research Archaeology from the British School of Athens. He was awarded the CSM<br />

in the 2006 Queens Birthday list for services to <strong>Navy</strong>’s heritage and as Manager of<br />

the RAN Heritage Centre.<br />

Mr John Perryman<br />

Mr John Perryman joined the <strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Navy</strong> in January 1980 as a 16-year-old<br />

junior recruit in HMAS Leeuwin in Western Australia. On completion of basic training<br />

he undertook category training as a signalman in HMAS Cerberus. His postings<br />

included service in HMA Ships and establishments Leeuwin, Cerberus, Harman,<br />

Kuttabul, Stalwart, Hobart, Stuart, Tobruk and Success as both a junior and senior<br />

sailor. Promoted to Warrant Officer Signals Yeoman in 1998 he served for three years<br />

as the Senior Instructor at the RAN Communications and Information Systems (CIS)<br />

School HMAS Cerberus, including a short notice secondment to HQ INTERFET in<br />

East Timor, where he served until INTERFET’s withdrawal in February 2000. He was<br />

commissioned a lieutenant in 2001, and remained at the CIS School until August 2002,<br />

at which time he was posted to Canberra to the RAN’s C4 directorate. He transferred<br />

to the Naval Reserve in 2004 and took up the position as the Senior Naval Historical<br />

Officer at the Sea Power Centre – Australia.

xvi<br />

AUSTRALIAN MARITIME ISSUES 2006: SPC-A ANNUAL<br />

Lieutenant Commander Anthony Powell, RAN<br />

Lieutenant Commander Powell joined the <strong>Navy</strong> in January 1979 and commissioned<br />

as a midshipman in 1982. He gained his Bridge Watchkeeping Certificate on HMAS<br />

Tobruk in 1987 and completed numerous sea postings as a watchkeeper, a navigator, a<br />

training officer and an executive officer. In early 2004, he was deployed to Iraq to lead<br />

an <strong>Australian</strong> naval contingent and, as the Coalition’s Director Operations and Training,<br />

raise the new Iraqi <strong>Navy</strong> for which he received a Commendation for Distinguished<br />

Service. He has commanded HMA Ships Betano, Cessnock, Armidale and Larrakia, and<br />

now commands the crew ‘Attack Two’ under the patrol boat multi crewing concept.<br />

Dr David Stevens<br />

Dr David Stevens has been the Director of Strategic and Historical Studies, Sea Power<br />

Centre - Australia, since retiring from full time naval service in 1994. He joined the<br />

<strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Australian</strong> Naval College in 1974 and completed a Bachelor of Arts degree at<br />

the University of New South Wales (UNSW). He undertook the <strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Navy</strong>’s Principal<br />

Warfare Officer course in 1984 and specialised in anti-submarine warfare. Thereafter<br />

he served as a warfare officer on exchange in HMS Hermione, and was one of the first<br />

<strong>Australian</strong>s to conduct a Falkland Islands peace patrol. In 1990-91 he was posted to<br />

the staff of the <strong>Australian</strong> Task Group Commander during Operation DAMASK and the<br />

1990-91 Gulf War. He graduated from the <strong>Australian</strong> National University with a Master<br />

of Arts (Strategic Studies) in 1992, and in 2000 received his Doctor of Philosophy in<br />

history from UNSW at the <strong>Australian</strong> Defence Force Academy.<br />

Commander Nicholas Stoker, RAN<br />

Commander Stoker joined the RAN in 1987 and graduated from the <strong>Australian</strong><br />

Defence Force Academy in 1989 with a Bachelor of Science. He is a qualified Principal<br />

Warfare Officer specialising in surface and anti-submarine warfare and holds a subspecialisation<br />

in Meteorology and Oceanography (METOC). He has served on exchange<br />

with the Canadian and United States navies, most recently as the Deputy Director<br />

ASW team training at the USN Fleet ASW Training Centre. His last sea posting was<br />

as commissioning Executive Officer of HMAS Parramatta. Following graduation from<br />

the <strong>Australian</strong> Command and Staff Course in December 2005, he was appointed Staff<br />

Officer Maritime Operations at Strategic Operations Division (now Military Strategic<br />

Commitments). He is to assume command of HMAS Newcastle in mid 2007.<br />

MCEAP II Kuldeep Singh Thakur<br />

MCEAP II Thakur joined the Indian <strong>Navy</strong> as an Artificer Apprentice in 1988. After<br />

completing a Diploma in Electrical Engineering in 1992, he served onboard various<br />

Indian naval ships and establishments. He is currently undertaking a Masters in<br />

Business Administration (Human Resource Management) and a Post Graduate

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

xvii<br />

Diploma in Management. He is currently posted to the Indian Naval Ship Maintenance<br />

Authority, Mumbai.<br />

Commander Peter Thompson, RAN<br />

Commander Peter Thompson joined the RAN in 1985, graduating from RANC in 1987.<br />

As an Officer of the Watch he served in HMA Ships Parramatta, Torrens, Perth and<br />

Brisbane and as Executive Officer of HMAS Warnambool. He graduated as a Principal<br />

Warfare Officer in 1997 and served as Anti-submarine Warfare officer in HMNZS<br />

Wellington and HMAS Newcastle. His most recent seagoing posting was as Executive<br />

Officer HMAS Tobruk. He has seen operational service in East Timor, the Solomon<br />

Islands and Bougainville. A graduate of the <strong>Australian</strong> Command and Staff Course, he<br />

is currently the Director of Operations at <strong>Navy</strong> Headquarters in Canberra.<br />

Lieutenant Commander Nick Watson, RAN<br />

Lieutenant Commander Nick Watson joined the RAN in 1988, and was awarded a<br />

Bachelor of Arts (Honours) in 1991 prior to conducting seaman officer training. After<br />

becoming an Officer of the Watch in HMAS Brisbane, he joined the submarine arm<br />

and served in six submarines, in positions up to Executive Officer. He graduated from<br />

<strong>Australian</strong> Command and Staff Course in 2006, and will assume command of Armidale<br />

class patrol boat crew Aware in 2007. He was awarded a Master of Arts (Maritime<br />

Policy) in 2003.<br />

Dr Stanley Weeks<br />

Dr Stanley Weeks is a senior scientist with Science Applications International<br />

Corporation, where he currently supports the US <strong>Navy</strong> on strategy and program issues.<br />

He served in the US <strong>Navy</strong> from 1970-90, and career highlights include being on the<br />

drafting team for the Maritime Strategy in 1982, serving in the State Department<br />

in 1985-86, commanding a Spruance class destroyer in 1987-88 and being a faculty<br />

member of the National War College in 1989-90. Since 1994 he has been an adjunct<br />

Professor at the US Naval War College. He has extensive policy experience in the Asia-<br />

Pacific and is a member of the Council for Security Cooperation in the Asia-Pacific<br />

and relevant study groups, as well as the International SLOC Conference. His most<br />

recent project responsibility was as the Senior Naval Adviser in Albania from June<br />

2004 to December 2005, where he planned and implemented the transformation of<br />

Albanian maritime forces.<br />

Dr Nial Wheate<br />

Dr Nial Wheate joined the <strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Navy</strong> in 1995 as an <strong>Australian</strong> Defence<br />

Force Academy midshipman. Following three years of study for a science degree, and a<br />

subsequent honours year, he was posted to the School of Chemistry, <strong>Australian</strong> Defence<br />

Force Academy as a Visiting Military Fellow. In 2000 he took two years leave from

xviii<br />

AUSTRALIAN MARITIME ISSUES 2006: SPC-A ANNUAL<br />

the RAN and was employed by the School as an Associate Lecturer, where he taught<br />

first year chemistry, while he completed his Doctorate in platinum-based anti-cancer<br />

drugs. He came back to full time naval service in 2002, and subsequently served in the<br />

Airworthiness and Coordination Policy Agency, Joint Health Support Agency and the<br />

Sea Power Centre - Australia. He resigned from the <strong>Navy</strong> in late 2005 and now works<br />

as a Senior Research Associate at the University of Western Sydney.<br />

Lieutenant Commander John Wright, RAN<br />

Lieutenant Commander John Wright has served in the RAN for 18 years as a<br />

marine engineering officer. He has served in HMA Ships Brisbane, Perth and in the<br />

commissioning crew of Parramatta. He has also worked in a number of project and<br />

engineering support roles, including the Landing Platform Amphibious project, the<br />

Amphibious and Afloat Sustainment System Program Office (AASSPO) and Ship<br />

Repair Contract Office (SRCO(EA)). He was promoted to commander in December<br />

2006 and is currently the Manager of SRCO(EA) before he returns to the AASSPO as<br />

the Sustainment Manager at the end of 2007.

xix<br />

Contents<br />

Papers in <strong>Australian</strong> Maritime Affairs<br />

Foreword<br />

Editors’ Note<br />

Contributors<br />

Abbreviations<br />

v<br />

vii<br />

ix<br />

xi<br />

xxiii<br />

OPENING PAPERS<br />

HMAS Anzac, Northern Trident and<br />

the 200th Anniverary of the Battle of Trafalgar 3<br />

Captain Richard Menhinick, CSC, RAN<br />

The Best Laid Staff Work: An Insider’s View of<br />

Jellicoe’s 1919 Naval Mission to the Dominions 11<br />

Dr Andrew Gordon<br />

SYNNOT LECTURES<br />

The 1000-Ship <strong>Navy</strong> Global Maritime Partnership Initiative 27<br />

Dr Stanley Weeks<br />

Transforming Maritime Forces:<br />

Capacity Building for Non-Traditional Challenges 37<br />

Dr Stanley Weeks<br />

RADFORD/COLLINS AGREEMENT (REVISED 1957)<br />

(Reprinted with minor amendments 1959) 47<br />

(Reprinted with minor amendments 1967) 57<br />

SEMAPHORE: JUNE 2005 — DECEMBER 2006<br />

The Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear Threat 71<br />

Dr Nial Wheate<br />

Blockading German East Africa, 1915-16 77<br />

Mr John Perryman

xx<br />

AUSTRALIAN MARITIME ISSUES 2006: SPC-A ANNUAL<br />

The <strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Navy</strong> and the Restoration of Stability<br />

in the Solomon Islands 83<br />

Mr Peter Laurence and Dr David Stevens<br />

The <strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Navy</strong> Heritage Centre 89<br />

Commander Shane Moore, CSM, RAN<br />

Trafalgar — 200 Years On 95<br />

Dr Gregory P. Gilbert<br />

The Strategic Importance of <strong>Australian</strong> Ports 99<br />

Mr Andrew Mackinnon<br />

Farewell to the Fremantle Class 105<br />

Mr Brett Mitchell<br />

Naval Ingenuity: A Case Study 111<br />

Mr John Perryman<br />

A First Analysis of RAN Operations, 1990-2005 117<br />

Mr Andrew Forbes<br />

Maritime Security Regulation 123<br />

Mr Andrew Forbes<br />

Welcome to the Armidale Class 129<br />

Commander Wesley Heron, RANR, and<br />

Lieutenant Commander Anthony Powell, RAN<br />

The RAN and the 1918-19 Influenza Pandemic 135<br />

Dr David Stevens<br />

Positioning Navies for the Future 141<br />

Commodore Jack McCaffrie, AM, CSM, RANR<br />

Visual Signalling in the <strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Navy</strong> 147<br />

Mr John Perryman<br />

Reading Our Way to Victory? 153<br />

Dr Gregory P. Gilbert<br />

The ‘Special Cruise’ of HMAS Gayundah — 1911 159<br />

Dr David Stevens<br />

Hot Pursuit and <strong>Australian</strong> Fisheries Law 165<br />

Lieutenant Commander Penny Campbell, RAN<br />

Operation ASTUTE — The RAN in East Timor 171<br />

Dr David Stevens

CONTENTS<br />

xxi<br />

The Effects of Weather on RAN Operations in the Southern Ocean 177<br />

Commander Andrew McCrindle, RAN, and<br />

Lieutenant Commander Rebecca Jeffcoat, RAN<br />

The Western Pacific Naval Symposium 183<br />

Mr Andrew Forbes<br />

Primary Casualty Reception Facility 189<br />

Lieutenant Commander Meg Ford, RAN<br />

Ancient Egyptian Joint Operations in The Lebanon Under<br />

Thutmose III (1451-1438 BCE) 195<br />

Dr Gregory P. Gilbert<br />

The RAN Band Ashore and Afloat 201<br />

Lieutenant Commander Phillip Anderson, OAM, RAN<br />

RAN Activities in the Southern Ocean 207<br />

Mr Andrew Forbes<br />

Women in the RAN: The Road to Command at Sea 213<br />

Lieutenant Andrea Argirides, RANR<br />

The Long Memory: RAN Heritage Management 219<br />

Commander Shane Moore, CSM, RAN<br />

PETER MITCHELL ESSAY COMPETITION<br />

About the Competition 227<br />

Regional Alliances in the Context of a Maritime Strategy 229<br />

Commander Jonathan Mead, RAN<br />

An Effects-Based Approach to Technology and Strategy 239<br />

Lieutenant Commander Mark Hammond, RAN<br />

Medium Sized Navies and Sea Basing: Brave as Lions<br />

and Cunning as Foxes 251<br />

Lieutenant Commander Nick Stoker, RAN<br />

Sea Basing and Medium Navies 261<br />

Commander Peter Thompson, RAN<br />

Generation X and <strong>Navy</strong> Workforce Planning 271<br />

MCEAP-II Kuldeep Singh Thakur

xxii<br />

AUSTRALIAN MARITIME ISSUES 2006: SPC-A ANNUAL<br />

The Relevance of Sun Tzu’s The Art of War to Contemporary<br />

Maritime Strategy 279<br />

Lieutenant Commander Nick Watson, RAN<br />

The Relevance of Maritime Forces to Asymmetric Threats 293<br />

Lieutenant Commander John Wright, RAN<br />

The Importance of Constabulary Operations 303<br />

Chief Petty Officer Robert Brimson<br />

Bibliography 315

xxiii<br />

Abbreviations<br />

2IC<br />

AAPMA<br />

AASFEG<br />

ACPB<br />

ACS<br />

ADF<br />

AFMA<br />

AFP<br />

AFZ<br />

AMDC<br />

AME<br />

AMF<br />

AMIS<br />

ANARE<br />

ANZUS<br />

AO<br />

APEC<br />

ASEAN<br />

ASIO<br />

ARF<br />

ARG<br />

ASW<br />

AWD<br />

BNH<br />

BWC<br />

C2<br />

Second in Command<br />

<strong>Australian</strong> Association of Ports and Marine Authorities<br />

Amphibious and Afloat Support Force Element Group<br />

Armidale Class Patrol Boat<br />

<strong>Australian</strong> Customs Service<br />

<strong>Australian</strong> Defence Force<br />

<strong>Australian</strong> Fisheries Management Authority<br />

<strong>Australian</strong> Federal Police<br />

<strong>Australian</strong> Fisheries Zone<br />

<strong>Australian</strong> Maritime Defence Council<br />

Aeromedical Evacuation<br />

Afloat Medical Facility<br />

<strong>Australian</strong> Maritime Identification System<br />

<strong>Australian</strong> National Antarctic Research Expeditions<br />

Security Treaty Between Australia, New Zealand and the United<br />

States of America 1951<br />

Area of Operations<br />

Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation<br />

Association of South East Asian Nations<br />

<strong>Australian</strong> Security Intelligence Organisation<br />

Association of Southeast Asian Nations Regional Forum<br />

Amphibious Ready Group<br />

Anti-Submarine Warfare<br />

Air Warfare Destroyer<br />

Balmoral Naval Hospital<br />

(Biological Weapons Convention) Convention on the Prohibition<br />

of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological<br />

(Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on their Destruction 1972<br />

Command and Control

xxiv<br />

AUSTRALIAN MARITIME ISSUES 2006: SPC-A ANNUAL<br />

C4I<br />

CB<br />

CBRN<br />

CDF<br />

CIWS<br />

CLF<br />

CN<br />

CNF<br />

CNO<br />

CO<br />

COLPRO<br />

COS<br />

CSG<br />

CUES<br />

CWC<br />

DDG<br />

DIO<br />

DIVEX<br />

DSTO<br />

EBO<br />

EEZ<br />

ESG<br />

FAAM<br />

FACE<br />

FCPB<br />

FFG<br />

FFV<br />

FGH<br />

Command, Control, Communications, Computers and<br />

Intelligence<br />

Chemical and Biological<br />

Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear<br />

Chief of Defence Force<br />

Close-In Weapons System<br />

Combat Logistics Force<br />

Chief of <strong>Navy</strong><br />

Commonwealth Naval Forces<br />

Chief of Naval Operations<br />

Commanding Officer<br />

Collective Protection<br />

Chief of Staff<br />

Carrier Strike Group<br />

Code for Unalerted Encounters at Sea<br />

(Chemical Warfare Convention) Convention on the Prohibition of<br />

the Development, Production, Stockpiling and use of Chemical<br />

Weapons and on their Destruction 1993<br />

Perth Class Guided Missile Destroyer<br />

Defence Intelligence Organisation<br />

Diving Exercise<br />

Defence Science and Technology Organisation<br />

Effects-Based Operations<br />

Exclusive Economic Zone<br />

Expeditionary Strike Group<br />

Fleet Air Arm Museum<br />

Forces Advisory Council on Entertainment<br />

Fremantle Class Patrol Boat<br />

Adelaide Class Frigate<br />

Foreign Fishing Vessels<br />

Federal Government House

ABBREVIATIONS<br />

xxv<br />

FMA<br />

Fisheries Management Act 1991 (Cth)<br />

FPDA Five Power Defence Arrangements 1971<br />

FWC<br />

Future Warfighting Concept<br />

FWOC<br />

Fleet Weather and Oceanography Centre<br />

G8<br />

Group of Eight<br />

ha<br />

hectare<br />

HIMI<br />

Heard Island and McDonald Islands<br />

HMAS<br />

Her Majesty’s <strong>Australian</strong> Ship<br />

HMS<br />

Her Majesty’s Ship<br />

HQJOC<br />

Headquarters Joint Operations Command<br />

HRD<br />

Human Resource Development<br />

HS<br />

Hydrographic Ship<br />

HSV<br />

High Speed Vessel<br />

IFF<br />

Identification, Friend or Foe<br />

IFM<br />

Isatabu Freedom Movement<br />

IFR<br />

International Fleet Review<br />

IFOS<br />

International Festival of the Sea<br />

IMO<br />

International Maritime Organization<br />

INCSEA Incidents at Sea<br />

INTERFET International Force East Timor<br />

IPE<br />

Individual Protective Equipment<br />

ISO<br />

International Organization for Standardization<br />

ISPS Code International Ship and Port Facility Security Code 2002<br />

ISS<br />

International Seapower Symposium<br />

JI<br />

Jemaah Islamiah<br />

JMC<br />

Joint Maritime Course<br />

JOPC<br />

Joint Offshore Protection Command<br />

JSF<br />

Joint Strike Fighter<br />

km<br />

kilometre<br />

LCM8 small amphibious transport (Landing Craft Mechanised Type 8)<br />

LHD<br />

amphibious assault ship (Landing Helicopter Dock)

xxvi<br />

AUSTRALIAN MARITIME ISSUES 2006: SPC-A ANNUAL<br />

LNG<br />

Liquified Natural Gas<br />

LOSC United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982<br />

LPA<br />

amphibious transport (Landing Platform Amphibious)<br />

LRIT<br />

Long Range Identification and Tracking<br />

LTTE<br />

Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam<br />

MASER<br />

Microwave Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation<br />

MCM<br />

Mine Countermeasures<br />

MCMEX Mine Countermeasures Exercise<br />

MEAO<br />

Middle East Area of Operations<br />

MEF<br />

Malaita Eagle Force<br />

METOC<br />

Meteorological and Oceanographic<br />

MFU<br />

Major Fleet Unit<br />

MIED<br />

Maritime Information Exchange Directory<br />

MPF<br />

Maritime Prepositioning Force<br />

MTOFSA Maritime Transport and Offshore Facilities Security Act 2003<br />

MTSA Maritime Transport Security Act 2003<br />

NATO<br />

North Atlantic Treaty Organisation<br />

NCAGS<br />

Naval Cooperation and Guidance for Shipping<br />

NCW<br />

Network Centric Warfare<br />

NFI<br />

Naval Fuel Installations<br />

NHC<br />

Naval Heritage Collection<br />

NHMS<br />

Naval Heritage Management Study<br />

NOC<br />

Naval Operations Concept<br />

nm<br />

nautical mile<br />

NQEA<br />

North Queensland Engineers and Agents<br />

NSP<br />

<strong>Navy</strong> Strategic Plan<br />

OIC<br />

Officer in Charge<br />

OMFTS<br />

Operational Manoeuvre from the Sea<br />

ONA<br />

Office of National Assessments<br />

OTHR<br />

Over the Horizon Radar<br />

PCRF<br />

Primary Casualty Reception Facility

ABBREVIATIONS<br />

xxvii<br />

PFI<br />

PfP<br />

PMC<br />

PNF<br />

PNT<br />

PPF<br />

PSI<br />

PWO<br />

QDR<br />

RAAF<br />

RAMSI<br />

RAN<br />

RANHC<br />

RANHF<br />

RANNS<br />

RANR<br />

RAS<br />

RHIB<br />

RN<br />

RNZN<br />

RoRo<br />

RPB<br />

R/T<br />

RUSI<br />

SAR<br />

SEATO<br />

SLAM<br />

SLOC<br />

Private Financing Initiative<br />

Partnership for Peace<br />

Private Military Company<br />

Permanent Naval Forces<br />

Peacetime National Tasks<br />

Participating Police Force<br />

Proliferation Security Initiative<br />

Principal Warfare Officer<br />

Quadrennial Defense Review<br />

<strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Australian</strong> Air Force<br />

Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands<br />

<strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Navy</strong><br />

<strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Navy</strong> Heritage Centre<br />

<strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Navy</strong> Historic Flight<br />

<strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Australian</strong> Naval Nursing Service<br />

<strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Australian</strong> Naval Reserve<br />

Replenishment at Sea<br />

Rigid Hull Inflatable Boat<br />

<strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Navy</strong><br />

<strong>Royal</strong> New Zealand <strong>Navy</strong><br />

Roll-on / Roll-off<br />

Replacement Patrol Boat<br />

Radio Telephony<br />

<strong>Royal</strong> United Services Institute<br />

Search and Rescue<br />

(Southeast Asia Treaty Organization) Southeast Asia Collective<br />

Defense Treaty and Protocol 1954<br />

Submarine Launched Anti-Aircraft Missile<br />

Sea Lines of Communication<br />

SOLAS International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea 1974<br />

SPC-A<br />

Sea Power Centre – Australia

xxviii<br />

AUSTRALIAN MARITIME ISSUES 2006: SPC-A ANNUAL<br />

STOVL<br />

SUA<br />

SWATH<br />

TAC<br />

TADIL<br />

UAV<br />

UK<br />

UN<br />

US<br />

USMC<br />

USN<br />

USS<br />

UUV<br />

V/S<br />

WMD<br />

WPNS<br />

WRANS<br />

W/T<br />

WWI<br />

WWII<br />

XO<br />

Short Take-Off / Vertical Landing<br />

(Suppression of Unlawful Acts Convention) Convention for the<br />

Suppression of Unlawful Acts Against the Safety of Maritime<br />

Navigation 1988<br />

Small Waterplane Area Twin Hull<br />

Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia<br />

Tactical Digital Information Link<br />

Uninhabited Aerial Vehicle<br />

United Kingdom<br />

United Nations<br />

United States<br />

United States Marine Corps<br />

United States <strong>Navy</strong><br />

United States Ship<br />

Uninhabited Underwater Vehicle<br />

Visual Signalling<br />

Weapons of Mass Destruction<br />

Western Pacific Naval Symposium<br />

Women’s <strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Australian</strong> Naval Service<br />

Wireless Telegraphy<br />

World War I<br />

World War II<br />

Executive Officer<br />

ZOPFAN Zone of Peace, Freedom and Neutrality Declaration 1971

Opening Papers

AUSTRALIAN MARITIME ISSUES 2006: SPC-A ANNUAL

HMAS Anzac, Northern Trident and the<br />

200th Anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar<br />

Captain Richard Menhinick, CSC, RAN<br />

For five and a half months in 2005, HMAS Anzac was away from <strong>Australian</strong> waters and<br />

our region conducting a deployment known as NORTHERN TRIDENT 05. Thousands of<br />

people from different nations have stepped across the gangway and enjoyed this piece<br />

of Australia, all the while enriching us with their cultures and way of life.<br />

This paper is predominantly about one of the key ceremonial events upon which the<br />

deployment was planned: the 200th anniversary celebrations for the Battle of Trafalgar.<br />

These celebrations centred on an International Fleet Review (IFR) in the Solent, off<br />

Portsmouth, England, in late June 2005. However, I feel it is important to set the<br />

context first and briefly outline other events, outcomes, achievements and benefits<br />

before describing the IFR itself.

AUSTRALIAN MARITIME ISSUES 2006: SPC-A ANNUAL<br />

It had been 15 years since a <strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Navy</strong> (RAN) ship visited Northern Europe,<br />

the last ship being HMAS Sydney in 1990. During this deployment Anzac has been<br />

privileged to visit ports in India, the Mediterranean, Europe and Africa, marking many<br />

firsts along the way. Needless to say highlights have been many, almost too numerous<br />

to list, with the ship’s company able to call this the ‘trip of a lifetime’. Importantly, from<br />

a professional perspective, the feedback from countries, foreign military services and<br />

<strong>Australian</strong> overseas missions confirm that the advantages of such deployments to the<br />

ship’s company, the RAN and the <strong>Australian</strong> Defence Force (ADF) range across the full<br />

spectrum from the diplomatic, through the commercial to the operational spheres.<br />

Significantly we have benefited operationally from close interaction with North<br />

Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) forces. As an example, the operational element<br />

of the deployment has included various passage exercises with the navies of Greece,<br />

Turkey, France and Germany, and a two week Joint Maritime Course (JMC) off Scotland<br />

consisting of some 50 ships, 5 submarines and over 80 aircraft. Operationally and<br />

tactically the JMC was a success. As already mentioned it had been 15 years since<br />

the RAN had deployed to the UK and Europe, and we were interested to measure our<br />

performance in their waters. I believe that the national aim of benchmarking RAN<br />

practice and capability was achieved. Anzac was able to integrate with the NATO<br />

units quickly and relatively easily. The JMC debrief contained many positives for<br />

Anzac and several favourable comments were made by the Task Group Commander’s<br />

staff regarding our conduct of operations, especially anti-submarine warfare (ASW)<br />

operations and the capability of Anzac’s sensors in the littoral, as well as our clear<br />

and effective control of assigned task group units. We think that the capabilities of<br />

the Anzac class FFH and, importantly, the personnel training standards and expertise<br />

of the RAN, were well demonstrated in that particular exercise and shown to be at<br />

world’s best practice.<br />

One significant event was the first use by an operational ADF unit of the Link-16<br />

Tactical Digital Information Link (TADIL). Link-16 proved to be a major aid to situational<br />

awareness and a very effective tool for command appreciation of the larger picture,<br />

especially while operating beyond the range of UHF voice communications. As there<br />

were many Link-16 fitted assets, including <strong>Royal</strong> Air Force (RAF) E3D aircraft and<br />

<strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Navy</strong> (RN) Airborne Early Warning Sea King helicopters, important progress<br />

was made in the RAN Link-16 evaluation during this period.<br />

This period of high intensity operations was followed immediately by a resumption of<br />

the diplomatic role that the ship had conducted throughout earlier visits to mainland<br />

European ports. The diplomatic role of sea power forms an integral part of our national<br />

strategy. During the NORTHERN TRIDENT 05 deployment the ship visited 13 countries<br />

and hosted, displayed and demonstrated <strong>Australian</strong> ingenuity, culture and industry<br />

ranging from <strong>Australian</strong> defence companies conducting seminars, tours and product<br />

demonstrations, to trade fairs featuring Western <strong>Australian</strong> wine and <strong>Australian</strong><br />

seafood.

HMAS Anzac, Northern Trident and the 200th Anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar<br />

<br />

Ceremonial commemorations have also featured strongly, with two in particular<br />

standing out: the privilege for the ship to be underway, close in shore in Anzac Cove<br />

on the 90th anniversary of the ANZAC landings; and for 95 of the ship’s company to<br />

be ashore at the Dawn Service and following commemoration ceremony at the Lone<br />

Pine Memorial. When dawn broke on Anzac Day, 25 April, those 95 members who<br />

were ashore were among the crowd at Anzac Cove, gathered to remember the ANZACs<br />

who fought on those very shores. Those left onboard had sailed the frigate into the<br />

cove at 0300, just 1200 yards from the beach, creating a breathtaking backdrop in<br />

the early morning quiet, with her entire silhouette, 5-inch gun and two 3-metre-high<br />

kangaroos all lit up, and had their own poignant Dawn Service aboard. Prime Minister<br />

John Howard said later in the day:<br />

To be at Anzac Cove on Anzac Day with HMAS Anzac in the<br />

background – well there’s nothing that makes you feel more proud to be<br />

an <strong>Australian</strong>.<br />

HMAS Anzac in Anzac Cove, dawn 25 April 2005<br />

The second occasion was the presence of Anzac as the <strong>Australian</strong> representative at<br />

the IFR to mark the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar and the subsequent<br />

International Festival of the Sea (IFOS), both at Portsmouth. This article is predominantly<br />

about our experiences in the IFR and IFOS celebrations, the link being not as apparent<br />

as some others with <strong>Australian</strong> history.<br />

In radio and television interviews with the <strong>Australian</strong> media, I was asked a few times:<br />

what was the connection with Australia and the Battle of Trafalgar? Well for most

AUSTRALIAN MARITIME ISSUES 2006: SPC-A ANNUAL<br />

it is certainly not as obvious as Gallipoli, the Battle of the Coral Sea or Kokoda, but<br />

in many ways it is just as crucial to Australia as any of these. The battle of course<br />

occurred in 1805, and in its simplest terms, the violence of it, and the resultant<br />

decisiveness of the British victory over the combined fleets of France and Spain, led<br />

to the century of sea power dominance that Britain then wielded on the world stage.<br />

The 100 years after Trafalgar were the heyday of the British Empire. With sea power<br />

and sea control came British world domination — not merely militarily, per se, but<br />

most importantly, economically. Sea control meant control of the world economies<br />

and also world trade.<br />

In 1805 Australia was a fledgling colony, susceptible to attack from foreign powers,<br />

very sparsely populated and largely unexplored. A victory by the combined fleets at<br />

Trafalgar, or even a stalemate, may have meant that Britain would not have dominated<br />

to the degree it subsequently did. The impact on Australia if that were the case makes<br />

interesting speculation. However, what is known is that the 100 years of British<br />

dominance that followed Trafalgar was the period in which Australia grew in peace<br />

and prosperity into the nation it became in 1901. A close and personal historic link with<br />

Trafalgar is perhaps a subject that we, as <strong>Australian</strong>s, should consider more often.<br />

So having established a context, what confronted Anzac off Portsmouth in the last week<br />

of June and first week of July 2005?<br />

The western half of the review anchorage area, with Cowes in the background<br />

While organised and controlled by the RN, the review included ships from 37 different<br />

countries, including Russia, France, Spain, South Korea, Nigeria, India, Japan and<br />

Serbia. Aside from small craft, tenders and the like, 176 ships participated in the review.<br />

They were all assigned anchorage positions in a 7.5 nm by 1.2 nm area of the Solent (an<br />

area of sheltered water between the Isle of Wight and the mainland of England). The

HMAS Anzac, Northern Trident and the 200th Anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar<br />

<br />

breakdown of major ship types included 5 aircraft carriers, 10 large amphibious ships<br />

and 40 destroyers/frigates, not to mention tankers, auxiliaries, corvettes, mine warfare<br />

vessels, submarines and countless others. This meant that the Solent was a spectacular<br />

sight and you will realise quickly that the available space was occupied fully.<br />

Anzac approached Portsmouth and the Solent on 23 June, having sailed from a short<br />

port visit in Cork, Ireland. Before entering harbour we launched our Seahawk helicopter<br />

to proceed to RAF Odiham in preparation for the helicopter flypast during the Fleet<br />

Review. On approaching Portsmouth we fired a 21-gun national salute, which was<br />

returned by HMS Invincible, and then proceeded alongside in the naval base. That first<br />

evening an official reception was held on board for 100 guests, at which the ship’s<br />

band and guard performed to rousing applause from all participants. Official onboard<br />

receptions have become a speciality in Anzac, the ship having conducted 13 during<br />

this deployment, all with the guard and band performing to critical acclaim, with the<br />

band’s live rendition of national anthems being particularly well received.<br />

The scope of activity conducted in the lead up to the Fleet Review precludes detailed<br />

listing. Suffice to say that the RN had put on a party, and the social and sporting<br />

events were significant. The review ships continued to arrive over the weekend<br />

up until 26 June and most went to anchor in the Solent, which led to a complicated<br />

liberty boat arrangement. Of course, the very real threat of terrorism was foremost in<br />

everyone’s minds and the force protection arrangements themselves were rigorous,<br />

comprehensive and effective.<br />

One big sporting event was the inaugural ‘<strong>Navy</strong> Ashes’. In this a cricket match was<br />

played between the Anzac Convicts cricket team and a team from seven RN ships.<br />

Anzac won the match, and the bails were burnt and sent home in an urn to Australia<br />

in the ship. The intention is to play for these ‘<strong>Navy</strong> Ashes’ on each occasion that a<br />

major unit of the RAN plays a major unit of the RN in cricket. Tradition of course has<br />

to start somewhere, and the 200th anniversary of Trafalgar seemed a good place to<br />

start another one.<br />

One of the highlights of the Fleet Review was that Anzac had been selected as one of<br />

six ships to conduct the underway steampast of Her Majesty the Queen. The steampast<br />

included four British ships, Anzac, and the Canadian ship HMCS Montreal, with Anzac<br />

number two in the column.<br />

Early on Monday 27 June, we departed port to rendezvous with the steampast squadron<br />

in the eastern approaches to the Solent. The day was programmed as a rehearsal for<br />

the Fleet Review, and all timings, formations and evolutions were executed to ensure<br />

no details were missed. The steampast squadron program called for a column in order<br />

of HMS Cumberland, HMAS Anzac, HMS Gloucester, HMCS Montreal, HMS Westminster<br />

and HMS Grafton, with initially 500 yards and later 300 yards between ships. After the<br />

rehearsal, Anzac remained at anchor overnight and I was fortunate enough to attend

AUSTRALIAN MARITIME ISSUES 2006: SPC-A ANNUAL<br />

the ‘Band of Brothers’ Dinner onboard Invincible with the Commanding Officers of<br />

participating ships. As the senior Commonwealth officer present, I found myself seated<br />

at the left side of the host, Commander-in-Chief Fleet, Admiral Sir Jonathon Band, KCB,<br />

RN. This was a most singular honour during a very pleasant evening.<br />

As part of the whole review we were keen to make the day itself as much of an <strong>Australian</strong><br />

and family event as we could. We knew from the rehearsal that the spectacle of sailing<br />

through about 170 ships was one we would probably never again witness. Hence on<br />

28 June, the day of the IFR, a large group of guests were embarked by boat, including<br />

staff of the High Commission in London and families of the ship’s company. Later<br />

that morning, at anchor off Cowes, several media personnel from the BBC, ABC and<br />

Channel 9 were embarked. They were destined to get a unique perspective of the event<br />

and shot some excellent file footage and conducted many interviews.<br />

HMAS Anzac and four units of the fast steampast squadron approaching<br />

the review position (HMS Endurance)<br />

The first stage of the Fleet Review involved Her Majesty sailing in HMS Endurance<br />

through two lines of anchored warships. This took about two hours and finished with<br />

Endurance anchoring at the head of the lines at the eastern extremity immediately past<br />

the aircraft carriers. Our squadron then weighed anchor for our easterly transit, which<br />

was about seven nautical miles long. Once under way, the guide’s speed was increased<br />

to 15, then 17 knots, and distance between ships was reduced to 300 yards. Even having

HMAS Anzac, Northern Trident and the 200th Anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar<br />

<br />

had a look at it in the simulator, the real view, both on the practice day and during the<br />

review, was stunning. The squadron timings had been worked out to the second, and<br />

Cumberland adjusted her speed over the ground to achieve them perfectly. The final<br />

result was the six ships passing Endurance at 300-yard intervals, about 100 yards off<br />

at 17 knots, manning and cheering ship as we did so. Those inclined to mental maths<br />

will have worked out that at 17 knots, 300 yards is covered in only 31.5 seconds, so<br />

Her Majesty was presented with about 2 minutes and 40 seconds of nearly continuous<br />

cheering. The feat was made even more spectacular by the fact that the weather was<br />

not kind with winds over the deck gusting in excess of 45 knots.<br />

The steampast was reportedly a spectacular sight from both ships in the line, and<br />

from Endurance. The opportunity was also taken by the steampast squadron to then<br />

pass close by the Cunard liner Queen Elizabeth 2 to complete the event. Our Seahawk<br />

helicopter participated in the helicopter flypast, as part of a formation of 16 aircraft,<br />

which immediately followed a large fixed wing flypast. The entire event was truly a<br />

magnificent sight, with 176 ships at anchor in the Solent, including an entire row of<br />

aircraft carriers, large amphibious ships and tankers.<br />

In good <strong>Australian</strong> tradition that evening, at anchor in St Helen’s Roads, a barbecue was<br />

held in the hangar for the ship’s company and guests. The weather conditions were not<br />

ideal, with squalls and choppy seas, but it cleared in time for the Son et Lumière, which<br />

took the form of a re-enactment of the battle followed by a massive fireworks display.<br />

While only the fireworks could be seen from our anchorage, it was a very pleasant sight<br />

at the end of a remarkable day. Another significant event, in what was already a day to<br />

remember and savour, was the <strong>Royal</strong> Reception and <strong>Royal</strong> Dinner in Invincible, that I<br />

attended with the Chief of <strong>Navy</strong>, Vice Admiral Chris Ritchie, AO, RAN; Mrs Ritchie; and<br />

Lieutenant Arno Tielens, RAN, my senior officer of the watch. At a special ceremony,<br />

Lieutenant Tielens was presented with the 2004 Queen’s Medal personally by Her<br />

Majesty the Queen, in the presence of His <strong>Royal</strong> Highness the Duke of Edinburgh; the<br />

First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Alan West, GCB, DSC, RN; Vice Admiral Chris Ritchie; Mrs<br />

Ritchie; and myself. Her Majesty the Queen’s Gold Medal is presented annually to the<br />

junior officer who has exhibited the most exemplary conduct, performance of duty and<br />

level of achievement while completing either initial entry or initial application training<br />

courses during the calendar year. This was the first time in its 89-year history that<br />

this award has been presented by the reigning monarch. During the reception, Her<br />

Majesty commented very favourably on the appearance of the steampast squadron,<br />

Anzac herself, and the spectacle the whole event presented.<br />

The IFR and its associated activities were an accurate foretaste of events as, early the<br />

next day, we proceeded alongside Portsmouth Naval Base in preparation for the IFOS.<br />

The ship’s Chaplain, Murray Lund, and the guard were landed by boat that morning<br />

to participate in the International Drumhead Ceremony at Southsea Common. Also,<br />

our helicopter left RAF Odiham, and moved to RAF Waddington to participate in the

10 AUSTRALIAN MARITIME ISSUES 2006: SPC-A ANNUAL<br />

Waddington International Air Show. The ship’s Flight did an excellent job representing<br />

the RAN, and Anzac won the award for best static display at the air show. Also of<br />

particular note, Her Majesty signalled RN and Commonwealth units participating in<br />

the Fleet Review to ‘Splice the Mainbrace’. This was most readily complied with; the<br />

ship’s company gathered on the flight deck for the occasion and enjoyed a couple of<br />

‘cold ones’ on behalf of the monarch as a reward for a job well done.<br />

With only a day to move in excess of 70 ships alongside from anchor, the RN did a<br />

fantastic job, and on 30 June the IFOS commenced. For Anzac this meant being open<br />

to visitors, with static displays of small arms, damage control equipment, a canteen<br />

stall selling ball caps and the like, and the band playing up a storm. The ship in effect<br />

became a concert stage for much of the day with Aussie songs booming out. While<br />

fewer ships were involved than in the Fleet Review, the IFOS was still conducted on<br />

a grand scale, with displays, stalls and stages covering every wharf in Portsmouth. In<br />

the first day alone, over 1500 people toured Anzac. The following three days brought<br />

the total to over 10,000 visitors to the ship. In order to meet the ship’s commitments<br />

during the IFOS, including various official receptions, the ship’s company was put<br />

in a two watch system (half on/half off in a 48 hour rotation). Many personnel used<br />

their off-watch time to visit London. It is estimated that over 275,000 people visited<br />

the naval base during IFOS.<br />

The whole IFR and IFOS experience was remarkable for Anzac, even amongst the very<br />

full months of NORTHERN TRIDENT 05. The spectacle of the Fleet Review is difficult<br />

to describe; watching the anchorage from St Helen’s Roads at sunset, with the masts<br />

of 176 ships in silhouette, was stirring. The experience of steaming through the lines<br />

in close formation is one not likely to be repeated in the careers of those involved, nor<br />

rivalled for its imagery. Additionally, the successful completion of the JMC exercise<br />

was a sure sign of the inherent flexibility of the surface combatant. To leave Hamburg<br />

in late May after much industry engagement and many receptions, then spend 12 days<br />

in company training for war at sea, only to reset for naval diplomacy 72 hours later,<br />

was indicative of the broad spectrum of actions a surface combatant can perform in<br />

support of Australia’s maritime strategy. Roll on the next deployment!

The Best Laid Staff Work: An Insider’s View of<br />

Jellicoe’s 1919 Naval Mission to the Dominions<br />

Dr Andrew Gordon<br />

I came to the subject of Admiral Jellicoe’s naval mission from an unlikely direction:<br />

my work-in-progress on Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay. The mastermind of the<br />

evacuation of Dunkirk, and the Allied naval commander in the invasion of Normandy,<br />

is not normally associated with the Pacific and Australasia. Yet, on New Year’s Day<br />

1945 — the day before he was killed in an air crash — had he been asked to name<br />

the most traumatic year of his life, it is probable that 1919, the year in which he was<br />

Staff Commander to Jellicoe on his odyssey round the Dominions to advise on their<br />

future naval policies, would be more likely a candidate than 1940 or 1944. To explain<br />

why, this paper has to be an unusual mix of the grand strategic and the intensely<br />

personal.<br />

The genesis of Jellicoe’s mission lay in the Imperial War Conference in 1918. The<br />

Admiralty tabled a plan for a single postwar Imperial <strong>Navy</strong>, controlled centrally, but<br />

had been rebuffed by the Dominion Prime Ministers who wanted their nations to<br />

‘develop navies of their own which would cooperate with that of Britain under one<br />

command established after the outbreak of any future war’. 1 They accepted that their<br />

forces must conform to <strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Navy</strong> (RN) standards and practices, and their lordships<br />

in the Admiralty were realistic enough to go along with this compromise. They also fell<br />

in with the Dominions’ expressed wish that they should be visited by a naval adviser<br />

of high credentials, as soon as the war was over, to help them plan and organise for<br />

their own naval defences accordingly.<br />

As a former Commander-in-Chief Grand Fleet and First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir John<br />

Jellicoe (as he still was when the voyage began) was the obvious choice: his name was<br />

known around the world and his reputation would command international respect.<br />

Further, his being out of sight from the seat of power, and out of mind, for an extended<br />

absence would not be intolerable to the present First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Rosslyn<br />

Wemyss, or indeed the next one in-waiting, Sir David Beatty. Jellicoe’s remit was:<br />

To advise the Dominion Authorities whether, in the light of the experience<br />

of the war, the scheme of naval organisation which has been adopted or<br />

may be in contemplation requires reconsideration, either from the point<br />

of view of the efficiency of that organisation for meeting local needs, or<br />

from that of ensuring the greatest possible homogeneity and cooperation<br />

between all the Naval Forces of the Empire. 2

12 AUSTRALIAN MARITIME ISSUES 2006: SPC-A ANNUAL<br />

He was to visit India, Australia, New Zealand and Canada, and the battlecruiser HMS<br />

New Zealand was made available for the cruise.<br />

As his Chief of Staff (COS), Jellicoe took with him Commodore Frederick Dreyer, who<br />

was by now his habitual retainer, having been his Flag-Captain in the Grand Fleet and<br />

then his Director of Naval Ordnance at the Admiralty. A large, overbearing man, Dreyer<br />

was a notorious bully, celebrated by historians as the inventor of ineffective fire-control<br />

gear. Dreyer recommended Commander Bertram Ramsay as Staff Commander. There<br />

is no evidence of any special link between the two, although they had served together<br />

twice: briefly in 1907 in the first commission of HMS Dreadnought, and then in early<br />

1914 in the battleship HMS Orion.<br />

Ramsay had been commanding the destroyer HMS Broke, in the Dover Patrol, for<br />

slightly more than a year. He had taken her over from the heroic Edward Evans, and<br />

proved himself an unbending martinet in pulling her back from near-anarchy. Very<br />

likely he had been chosen for that purpose: ‘his concern for discipline was out of the<br />

ordinary and was recognised as such by both his ship’s companies and his superiors’. 3<br />

The Dover Patrol also supplied the Flag Lieutenant, Vaughan Morgan, who had been<br />

‘flags’ to Sir Roger Keyes of Zeebrugge fame, and was thus already well known to<br />

Ramsay. Three other officers were carried, to advise on anti-submarine, mining and<br />

air matters. For Jellicoe’s small, select band, it was barely conceivable that they might<br />

refuse such an appointment. It was highly prestigious, promised many months of<br />

glamour and adventure, and resolved the anxieties about their immediate future that<br />

no doubt accompanied the prospect of postwar demobilisation.<br />

Ramsay duly handed over his destroyer — having told his diary: ‘am happy to think I<br />

shall pay off Broke a much improved ship in every way’ — and went down to Portsmouth<br />

to join New Zealand on 19 February. That afternoon he went to see his friend and<br />

near-senior, Commander James Somerville, at the Signal School for experimental<br />