The Journal of the Siam Society Vol. LXXX, Part 1-2, 1992 - Khamkoo

The Journal of the Siam Society Vol. LXXX, Part 1-2, 1992 - Khamkoo

The Journal of the Siam Society Vol. LXXX, Part 1-2, 1992 - Khamkoo

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Journal</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Siam</strong> <strong>Society</strong><br />

VOLUME 80, PART 1<br />

<strong>1992</strong>

©<br />

All Rights Reserved<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Siam</strong> <strong>Society</strong><br />

<strong>1992</strong><br />

ISSN 0857-7099<br />

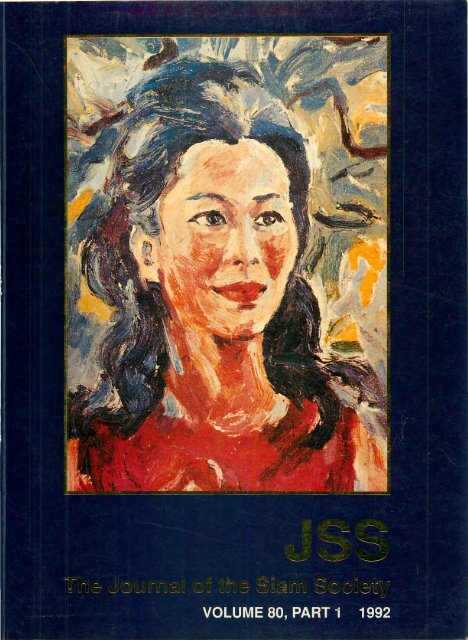

Front cover :<br />

Her Majesty Queen Sirikit. Portrait painted by Piriya Krairiksh, Bhubing Palace, Chiang Mai, 1964.<br />

Printed by<br />

Amarin Printing Group Co., Ltd., 65/16 Soi Wat Chaiyapruk, Pinklao-Nakhon Chaisi Road, Taling Chan,<br />

Bangkok 10170, Thailand. Tel. 424-2800-1, 424-1176

THE SIAM SOCIETY<br />

PATRON<br />

VICE-PATRONS<br />

HON. PRESIDENT<br />

HON. VICE-PRESIDENTS<br />

HON. MEMBERS<br />

HON. AUDITOR<br />

HON. ARCHITECT<br />

HON. LEGAL COUNSEL<br />

HON. LANDSCAPE CONSULTANT<br />

His Majesty <strong>the</strong> King<br />

Her Majesty <strong>the</strong> Queen<br />

Her Royal Highness <strong>the</strong> Princess Mo<strong>the</strong>r<br />

His Royal Highness Crown Prince Maha Vajiralongkorn<br />

Her Royal Highness Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn<br />

Her Royal Highness Princess Galyani Vadhana<br />

Her Royal Highness Princess Galyani Vadhana<br />

Mom Kobkaew Abhakara na Ayudhaya<br />

H.S.H. Prince Subhadradis Diskul<br />

Maj. Gen. M.R. Kukrit Pramoj<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Chilli Tingsabadh<br />

<strong>The</strong> Ven. Dhammaghosacariya (Buddhadasa Bhikkhu)<br />

<strong>The</strong> Ven. Debvedi (Payutto)<br />

Dr. Fua Haripitak<br />

Dr. Puey Ungphakorn<br />

Dr. Sood Saengvichien<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor William Gedney<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Prawase Wasi, M.D.<br />

H.E. Mr. Anand Panyarachun<br />

Dr. Tern Smitinand<br />

Mr. Dacre F.A. Raikes<br />

Mr. Yukta na Thalang<br />

Mr. Sirichai Narumit<br />

Mr. John Hancock<br />

Mr. William Warren<br />

COUNCIL OF THE SIAM SOCIETY FOR <strong>1992</strong>/93<br />

Dr. Piriya Krairiksh<br />

Dr. Rachit Buri<br />

Mrs. Jada Wattanasiritham<br />

Dr. Philippe Annez<br />

Mrs. Bilaibhan Sampatisiri<br />

Dr. Charit Tingsabadh<br />

Mr. Jitkasem Sangsingkeo<br />

Dr. Warren Y. Brockelman<br />

Mr. James V. Di Crocco<br />

Dr. Chaiyudh Khantaprab<br />

Mrs. Boonyavan Chandrviroj<br />

MEMBERS OF THE COUNCIL:<br />

Mr. Athueck Asvanund<br />

Major Suradhaj Bunnag<br />

Mr. Bangkok Chowkwanyun<br />

Mrs. Bonnie Davis<br />

Mrs. Virginia M. Di Crocco<br />

M.L. Plaichumpol Kitiyakara<br />

Mr. Henri Pagau-Clarac<br />

Mr. Norman Pajasalmi<br />

President<br />

Vice President<br />

Vice President<br />

Vice President<br />

Honorary Secretary<br />

Honorary Treasurer<br />

Honorary Librarian<br />

Honorary Editor <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> NHB<br />

Honorary Editor <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> JSS<br />

Leader <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Natural History Section<br />

Honorary Officer<br />

Mrs. Vipavadee Patpongpibul<br />

Mr. Peter Rogers<br />

Dr. Thawatchai Santisuk<br />

Mr.Barent Springsted<br />

Mr. Sidhijai Tanphiphat<br />

Dr. Steven J. Torok<br />

Mr. Albert Paravi Wongchirachai

Acknowledgments<br />

<strong>The</strong> Honorary Editor gives special thanks to <strong>the</strong><br />

President <strong>of</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Siam</strong> <strong>Society</strong> Under Royal Patronage,<br />

Dr. Piriya Krairiksh, for kindly furnishing to <strong>the</strong> JSS <strong>the</strong> reproduction<br />

<strong>of</strong> his painting <strong>of</strong> Her Majesty Queen Sirikit which<br />

graces our cover. Our readers are undoubtedly aware that<br />

Dr. Piriya is as accomplished a creative artist as he is a scholar.<br />

<strong>The</strong> photographer who took <strong>the</strong> cover picture <strong>of</strong> Her<br />

Royal Highness Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn for our<br />

previous issue, <strong>Vol</strong>. 79, <strong>Part</strong> 2, is Miss Anothai Nanthithasana,<br />

whose name was inadvertently omitted. She also took <strong>the</strong><br />

o<strong>the</strong>r pictures <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Princess which appear in that issue.<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r photographer to whom credit is belatedly<br />

due is Mr. Denis Robinson <strong>of</strong> Placitas, New Mexico. <strong>The</strong><br />

statement, originally included, that Mr. Robinson took all <strong>the</strong><br />

o<strong>the</strong>rwise unaccredited photographs illustrating <strong>the</strong> article on<br />

"Comparison <strong>of</strong> Transitional Bencharong and Probable Bat<br />

Trang Enameled Wares" by his wife, Mrs. Natalie Robinson,<br />

also in <strong>Vol</strong>. 79, <strong>Part</strong> 2, somehow fell out in <strong>the</strong> production<br />

process.<br />

We also extend our thanks to photographers<br />

Luca Invernizzi Tettoni, Dacho Buranabunpot, Noppadol<br />

Suwanweerakorn and Virginia Di Crocco for <strong>the</strong>ir contributions<br />

to <strong>the</strong> present issue, and to <strong>the</strong> Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam,<br />

for <strong>the</strong> photograph <strong>of</strong> a Dutch artist's painting <strong>of</strong><br />

Ayudhya. Specific credits are given in <strong>the</strong> appropriate places.<br />

Last in mention but among <strong>the</strong> first deserving <strong>of</strong> our<br />

appreciation is Mr. Euayporn Kerdchouay, whose assistance<br />

in <strong>the</strong> production <strong>of</strong> this issue was as invaluable as it always<br />

has been in many aspects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Society</strong>'s activities.

In This Issue<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Siam</strong> <strong>Society</strong> Under Royal Patronage most humbly<br />

and respectfully <strong>of</strong>fers this issue <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Siam</strong><br />

<strong>Society</strong> to Her Majesty QUEEN SIRIKIT in commemoration <strong>of</strong><br />

Her Majesty's Fifth Cycle Birthday, thus joining <strong>the</strong> entire<br />

nation in expressing affection and happiness on this most<br />

auspicious occasion. Council Member BONNIE DAVIS, <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Society</strong>'s chronicler <strong>of</strong> royalty, speaks for <strong>the</strong> <strong>Society</strong> as a whole<br />

in a warm-hearted tribute to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Society</strong>'s Royal Vice-Patron.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Siam</strong> <strong>Society</strong> also warmly welcomes His Royal<br />

Highness Crown Prince MAHA V AJIRALONGKORN as a<br />

Royal Vice-Patron, deeply sensible <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> high honor thus<br />

brought to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Society</strong>, and fur<strong>the</strong>r reports upon His Royal<br />

Highness's graciously representing His Majesty <strong>the</strong> King at<br />

<strong>the</strong> Gold-Casting Ceremony for <strong>the</strong> <strong>Society</strong>'s Buddha Footprint<br />

Project in honor <strong>of</strong> Her Majesty <strong>the</strong> Queen.<br />

Distinguished personages who have received honors<br />

<strong>of</strong> special interest to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Society</strong>, namely H.E. Mr. ANAND<br />

PANYARACHUN, Dr. TEM SMITINAND, Mr. DACRE F.A.<br />

RAIKES, O.B.E., and Mr. JAN. J. BOELES, are given recognition<br />

in <strong>the</strong> following pages.<br />

Members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Siam</strong> <strong>Society</strong> finally met <strong>the</strong>ir counterparts<br />

in <strong>the</strong> Malaysian Branch <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Royal Asiatic <strong>Society</strong><br />

during a gala weekend spent enjoying <strong>the</strong> hospitality <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

MBRAS in Penang, Kuala Lumpur, and at cultural monuments<br />

elsewhere in Malaysia. A return visit to Bangkok by<br />

<strong>the</strong> MBRAS is being planned.<br />

It is a pleasure indeed to announce that this issue <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> JSS has been sponsored by Mrs. BOONKRONG<br />

INDHUSOPHON, to whom goes our great gratitude. Mrs.<br />

Boonkrong's late husband, Mr. PRAKAIPET INDHUSOPHON,<br />

<strong>the</strong> renowned philatelist, had in his collection <strong>the</strong> contemporary<br />

letter <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> English merchant WILLIAM SOAME,<br />

presented in this issue, which describes <strong>the</strong> violent events <strong>of</strong><br />

1688 in <strong>Siam</strong>. Soame's letter, published here for presumably<br />

<strong>the</strong> first time, serves to introduce a discussion in several articles<br />

<strong>of</strong> various aspects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> history <strong>of</strong> Ayudhya.<br />

Featured among <strong>the</strong>se is a fresh and detailed scrutiny<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> architecture <strong>of</strong> Ayudhya by Dr. PIRIYA KRAIRIKSH,<br />

President <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Siam</strong> <strong>Society</strong>, in which he proposes a revised<br />

dating for many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> monuments in that city. Prominent in<br />

<strong>the</strong> evidence that he adduces are <strong>the</strong> descriptions, literary<br />

and pictorial, made by early European visitors to A yudhya,<br />

whose eyewitness accounts he compares with <strong>the</strong> monuments<br />

as <strong>the</strong>y have been traditionally described or dated and as<br />

<strong>the</strong>y appear today.<br />

We turn <strong>the</strong>n to politicoeconomic accounts <strong>of</strong><br />

A yudhya, some <strong>of</strong> which bear a close relation to <strong>the</strong> stormy<br />

events recounted by William Soame. His Excellency GEORGE<br />

A. SIORIS, formerly Ambassador <strong>of</strong> Greece in Thailand and<br />

Member <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Council, discusses <strong>the</strong> character <strong>of</strong> Constance<br />

Phaulkon as reconstituted by a fellow Greek. DIRK VAN<br />

DER CRUYSSE summarizes <strong>the</strong> broader scope <strong>of</strong> <strong>Siam</strong>ese<br />

French relations during <strong>the</strong> eighteenth century as a whole,<br />

examining <strong>the</strong>m in relation to a panoramic historical perspective,<br />

especially as concerns early <strong>Siam</strong>ese encounters with<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r Europeans besides <strong>the</strong> French. REIKO HADA, awardwinning<br />

Japanese novelist, studies Phaulkon's Japanese wife<br />

in a manner similar to that <strong>of</strong> Greek Ambassador Sioris's<br />

examining <strong>the</strong> Greek Phaulkon. CHARNVIT KASETSIRI<br />

depicts <strong>the</strong> role played by overseas Chinese traders in <strong>the</strong><br />

maritime economy <strong>of</strong> Ayudhya in its heyday. MICHAEL<br />

WRIGHT next turns his historian's telescope not back at<br />

Ayudhya from <strong>the</strong> present day, but forward to Ayudhya from<br />

prehistoric times.<br />

Here we leave Ayudhya for wider horizons as SUNAIT<br />

CHITINTARANOND examines <strong>the</strong> Thai image <strong>of</strong> Ayudhya's<br />

nemesis, <strong>the</strong> Burmese, and how that image <strong>of</strong> an implacable<br />

enemy was used to serve <strong>the</strong> goals <strong>of</strong> Thai patriotism. With<br />

CHRISTIAN BAUER we enter an entirely different arena as<br />

he focuses his epigrapher's scrutiny on <strong>the</strong> language <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Jataka glosses at Wat Sri Chum in Sukhothai; and with<br />

STEPHEN J. TOROK we view <strong>the</strong> future <strong>of</strong> Cambodia, and<br />

indeed <strong>of</strong> a stable self-sustainable world, as envisioned by a<br />

philosophical political economist with farreaching historical<br />

insights who was on <strong>the</strong> spot in Cambodia helping <strong>the</strong> UN to<br />

help Cambodia elect a new government.<br />

PETER SKILLING, looking into Sou<strong>the</strong>ast Asian<br />

maritime history, notes references to a pair <strong>of</strong> ports in<br />

Suvarnabhumi, and brings readers up to date on half a dozen<br />

recent translations <strong>of</strong> Buddhist literature ranging from Pali<br />

through Sanskrit and Tibetan.<br />

Finally, after our review section, JAN J. BOELES calls<br />

upon Catullus in seeking a fitting threnody for a towering<br />

figure among Thai scholars who will ever live in <strong>the</strong> annals<br />

<strong>of</strong> Lanna culture and <strong>the</strong> <strong>Siam</strong> <strong>Society</strong>, KRAISRI<br />

NIMMANAHAEMINDA, who passed away in May <strong>1992</strong>.<br />

Acharn Kraisri's luminous scholarship will cast an eternal light.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Journal</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Siam</strong> <strong>Society</strong><br />

VOLUME 80, PART 1<br />

<strong>1992</strong><br />

CONTENTS<br />

Acknowledgments 4<br />

In This Issue 5<br />

Section I : Her Majesty <strong>the</strong> Queen 9<br />

HER MAJESTY QUEEN SIRIKIT 11<br />

BONNIE DAVIS<br />

Section II : People and Events 13<br />

A GREAT HONOR FOR THE SIAM SOCIETY 14<br />

HONORS TO DISTINGUISHED PERSONS 15<br />

THE SIAM SOCIETY CEMENTS TIES 16<br />

WITH THE MALAYSIAN BRANCH OF THE<br />

ROYAL ASIA TIC SOCIETY<br />

Section III : A Contemporary Letter 17<br />

About <strong>the</strong> Events <strong>of</strong> 1688<br />

MRS. BOONKRONG INDHUSOPHON 19<br />

PRAKAIPET INDHUSOPHON 21<br />

A CONTEMPORARY LETTER 24<br />

BY AN ENGLISH MERCHANT<br />

ABOUT THE CRISIS IN SIAM, 1688<br />

Section IV : A yudhya Architecture 35<br />

A REVISED DATING OF 37<br />

A YUDHYA ARCHITECTURE<br />

BONNIE DAVIS<br />

WILLIAM SOAME<br />

PIRIYA KRAIRIKSH

7<br />

Section V : Aspects <strong>of</strong> Ayudhya 57<br />

PHAULKON 59<br />

A Personal Attempt at<br />

Reconstituting a Personality<br />

ASPECTS OF SIAMESE-FRENCH RELATIONS 63<br />

DURING THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY<br />

MADAME MARIE GUIMARD 71<br />

Under <strong>the</strong> Ayudhya Dynasty<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Seventeenth Century<br />

AYUDHYA: CAPITAL-PORT OF SIAM 75<br />

AND ITS CHINESE CONNECTION IN THE<br />

FOURTEENTH AND FIFTEENTH CENTURIES<br />

AYUDHYA AND ITS PLACE 81<br />

IN PRE-MODERN SOUTHEAST ASIA<br />

Section VI : O<strong>the</strong>r Articles 87<br />

THE IMAGE OF THE BURMESE ENEMY 89<br />

IN THAI PERCEPTIONS AND<br />

HISTORICAL WRITINGS<br />

THE WAT SRI CHUM JATAKA GLOSSES 105<br />

RECONSIDERED<br />

AN INFORMATION STRATEGY 127<br />

FOR ECONOMIC MODERNIZATION<br />

Section VII: Notes and Comments 129<br />

TWO PORTS OF SUV ARNABHUMI : 131<br />

A BRIEF NOTE<br />

Section VIII : Reviews 133<br />

REVIEW ARTICLE 135<br />

BUDDHIST LITERATURE:<br />

SOME RECENT TRANSLATIONS<br />

DIRK VAN DER CRUYSSE 144<br />

Louis XIV et le <strong>Siam</strong><br />

DIRK VAN DER CRUYSSE 146<br />

Louis XIV et le <strong>Siam</strong><br />

GEORGE A. SIORIS<br />

DIRK VAN DER CRUYSSE<br />

REIKO HADA<br />

CHARNVIT KASETSIRI<br />

MICHAEL WRIGHT<br />

SUNAIT CHUTINTARANOND<br />

CHRISTIAN BAUER<br />

STEVEN J. TOROK<br />

PETER SKILLING<br />

PETER SKILLING<br />

GEORGE A. SIORIS<br />

MICHAEL SMITHIES

8<br />

MICHEL JACQ-HERGOUALC'H 148<br />

Etude historique et critique<br />

du "<strong>Journal</strong> du Voyage de <strong>Siam</strong><br />

de Claude Ceberet,"<br />

Envoye extraordinaire du Roi<br />

en 1687 et 1688<br />

SULAK SIV ARAKSA 151<br />

Seeds <strong>of</strong> Peace:<br />

A Buddhist Vision for<br />

Renewing <strong>Society</strong><br />

SULAK SIV ARAKSA 151<br />

<strong>Siam</strong> in Crisis:<br />

A Collection <strong>of</strong> Articles<br />

MARTIN STUARY-FOX and 152<br />

MARY KOOYMAN<br />

Historical Dictionary <strong>of</strong> Laos<br />

CHARLES HIGHAM 156<br />

<strong>The</strong> Archaeology <strong>of</strong> Mainland Sou<strong>the</strong>ast Asia<br />

From 10,000 B.C. to <strong>the</strong><br />

Fall <strong>of</strong> Angkor<br />

J.H.C.S. DAVIDSON, ed. 158<br />

Austroasiatic Languages:<br />

Essays in Honor <strong>of</strong><br />

H.L. Shorto<br />

APINAN POSHYANANDA 159<br />

Modern Art in Thailand:<br />

Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries<br />

K.R. NORMAN, ed. 162<br />

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Pali Text <strong>Society</strong><br />

<strong>Vol</strong>ume XIV<br />

Section IX : In Memoriam 165<br />

KRAISRI NIMMANAHAEMINDA 167<br />

MICHAEL SMITHIES<br />

RUTH-INGE HEINZE<br />

JANE KEYES<br />

JAMES R. CHAMBERLAIN<br />

PAJRAPONGS NA POMBEJRA<br />

JAMES R. CHAMBERLAIN<br />

JOHN HOSKIN<br />

PETER SKILLING<br />

JAN J. BOELES

SECTION I<br />

HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN

Her Majesty Queen Sirikit graciously signs <strong>the</strong> <strong>Siam</strong> <strong>Society</strong>'s Welcome Book at <strong>the</strong> dedication<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Library, 13 January 1962.<br />

Her Majesty Queen Sirikit with Her Majesty Queen Ingrid <strong>of</strong> Denmark at <strong>the</strong> dedication<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Library <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Siam</strong> <strong>Society</strong>, 13 January 1962. <strong>The</strong> Library was dedicated in <strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong><br />

two kings and three queens : <strong>The</strong>ir Majesties King Bhumibol Adulyadet and Queen Sirikit <strong>of</strong><br />

Thailand, Her Majesty Queen Rambhai Barni, and <strong>The</strong>ir Majesties King Frederik IX and Queen<br />

Ingrid <strong>of</strong> Denmark.

HER MAJESTY QUEEN SIRIKIT<br />

BONNIE DAVIS<br />

MEMBER OF THE COUNCIL<br />

THE SIAM SOCIETY<br />

Her Majesty Queen Sirikit was born Mom Rajawongse<br />

Sirikit Kittiyakara on Friday, 12 August 1932. Her Majesty,<br />

<strong>the</strong> daughter <strong>of</strong> General H.R.H. Prince Nakkhatra Manggala<br />

Kittiyakara and Mom Luang Bua Kittiyakara, is descended<br />

from a long and illustrious royal lineage.<br />

At <strong>the</strong> age <strong>of</strong> four, M.R. Sirikit was enrolled in kindergarten<br />

at <strong>the</strong> Rajini School. During World War II she<br />

transferred to <strong>the</strong> St. Francis Xavier Convent School because<br />

it was closer to her home and considered safer. During <strong>the</strong><br />

years her fa<strong>the</strong>r served as <strong>the</strong> <strong>Siam</strong>ese Ambassador to several<br />

countries in Europe, M.R. Sirikit continued her education in<br />

England and France. Pr<strong>of</strong>icient in languages and music, she<br />

at one time considered becoming a concert pianist.<br />

It was in Europe where <strong>the</strong> young bachelor King <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Siam</strong> met <strong>the</strong> lovely M.R. Sirikit-a meeting that not only<br />

changed her life forever, but in time, <strong>the</strong> lives <strong>of</strong> thousands <strong>of</strong><br />

Thai people as well. <strong>The</strong>ir engagement was announced in<br />

1949, after months <strong>of</strong> rumors, speculation and hope at home.<br />

<strong>The</strong> young couple returned to <strong>Siam</strong> early in 1950 and were<br />

married on 28 April at Sapatum Palace, home <strong>of</strong> Her Majesty<br />

Queen Sawang Wattana, paternal grandmo<strong>the</strong>r <strong>of</strong> His Majesty<br />

<strong>the</strong> King.<br />

On his Coronation Day, 5 May 1950, His Majesty elevated<br />

his beautiful consort to <strong>the</strong> full rank and title <strong>of</strong> Her<br />

Majesty Queen Sirikit.<br />

<strong>The</strong>ir Majesties <strong>the</strong> King and Queen have four children,<br />

one son and three daughters. <strong>The</strong>ir first child, Princess Ubolratana,<br />

was born in April, 1951 in Switzerland, where His<br />

Majesty was continuing his formal education. <strong>The</strong>ir Majesties<br />

returned home to Thailand in December, 1951. <strong>The</strong><br />

Kingdom rejoiced, and <strong>the</strong> celebrations for His Majesty's<br />

birthday on 5 December were especially festive, for after almost<br />

twenty years <strong>the</strong>re were again a King and Queen in<br />

residence in <strong>the</strong> Royal Palace. His Royal Highness Prince<br />

Maha Vajiralongkorn was born in Bangkok on 28 July 1952,<br />

<strong>the</strong> first son born to a reigning King <strong>of</strong> <strong>Siam</strong> since 1893. Her<br />

Royal Highness Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn was born<br />

on 2 April1955, and Her Royal Highness Princess Chulabhorn<br />

on 4 July 1957.<br />

Although she was very young when she became a<br />

mo<strong>the</strong>r, Her Majesty soon became <strong>the</strong> role model for Thai<br />

mo<strong>the</strong>rs. Since 1976 <strong>the</strong> Queen's birthday on 12 August has<br />

been celebrated as National Mo<strong>the</strong>r's Day in Thailand. Once<br />

asked about her favorite hobbies by a television interviewer<br />

in <strong>the</strong> United States, Her Majesty replied, "Looking after my<br />

children." <strong>The</strong> Royal children were brought up to be aware<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir duties as citizens <strong>of</strong> Thailand as well as members <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Royal Family. <strong>The</strong>y were also taught to use <strong>the</strong>ir time<br />

wisely, and Her Majesty <strong>of</strong>ten read to her children to encourage<br />

<strong>the</strong>m to read worthwhile books for pleasure as well as<br />

learning.<br />

Early in <strong>the</strong> reign <strong>The</strong>ir Majesties <strong>the</strong> King and Queen<br />

began visiting rural villages and provincial areas <strong>of</strong> Thailand<br />

so <strong>the</strong>y could meet <strong>the</strong>ir people, learn about <strong>the</strong>ir lives, and<br />

let <strong>the</strong>m know <strong>the</strong>y cared about <strong>the</strong>ir welfare. <strong>The</strong>y were<br />

amazed to find people waiting for <strong>the</strong>m everywhere <strong>the</strong>y<br />

went-along roadsides, at village markets and temples. Many<br />

had travelled on foot for days from areas where <strong>the</strong>re were<br />

no roads, and <strong>of</strong>ten bringing with <strong>the</strong>m small tokens or gifts<br />

<strong>the</strong>y hoped to present to <strong>the</strong>ir King and Queen. Hand woven<br />

cloth, choice fruits and vegetables, and frequently flowers<br />

which soon became very wilted in <strong>the</strong> heat. Everything was<br />

graciously received by <strong>The</strong>ir Majesties-nothing was refused.<br />

His Majesty once remarked that whatever else happened, <strong>the</strong>y<br />

would not go hungry!<br />

Her Majesty Queen Sirikit is <strong>the</strong> only Queen <strong>of</strong> this<br />

country to visit every province. When His Majesty entered<br />

<strong>the</strong> monastery for a short period, following <strong>the</strong> traditional<br />

custom <strong>of</strong> all young Thai men, Her Majesty served <strong>the</strong><br />

Kingdom as Regent while <strong>the</strong> King was absent from <strong>the</strong> throne.<br />

After His Majesty <strong>the</strong> King again assumed <strong>the</strong> duties <strong>of</strong><br />

Sovereign, <strong>the</strong> title <strong>of</strong> Somdej Phra Borom Rajini Nath, or "full<br />

reigning Queen," was bestowed on Her Majesty.<br />

Being born Royal isn't altoge<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> easy and idle life<br />

that many believe it to be-at least not in Thailand. <strong>The</strong>re is<br />

total commitment to <strong>the</strong> job at hand; always public expectations<br />

to fulfill, formal and <strong>of</strong>ten tiring ceremonial duties to<br />

perform, all in <strong>the</strong> task <strong>of</strong> trying to please everyone, disappoint<br />

no one, and keep smiling.<br />

That first trip <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Royal couple to visit <strong>the</strong>ir people<br />

expanded to become annual visits to widely separated regions<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> country. As time passed <strong>the</strong>y saw that <strong>the</strong> lives <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

people were becoming worse instead <strong>of</strong> better; clearly<br />

something had to be done. In trying to find solutions to rural<br />

problems, at one time <strong>The</strong>ir Majesties were spending close to<br />

eight months <strong>of</strong> every year away from Bangkok. As soon as<br />

<strong>the</strong> Royal children were old enough, <strong>the</strong>y too accompanied<br />

<strong>the</strong> King and Queen. To see <strong>the</strong>ir Royal Family visiting <strong>the</strong>m<br />

gave <strong>the</strong> people hope, but more than hope was needed.<br />

While His Majesty <strong>the</strong> King worked with <strong>the</strong> farmers<br />

to improve <strong>the</strong>ir lot, Her Majesty <strong>the</strong> Queen turned her attention<br />

to helping <strong>the</strong> women find ways to supplement <strong>the</strong><br />

family income. <strong>The</strong> ideal was to keep <strong>the</strong> family toge<strong>the</strong>r and<br />

for <strong>the</strong> women in <strong>the</strong> household to earn money while working<br />

at home.

12<br />

Thailand has a rich heritage <strong>of</strong> arts and handicrafts,<br />

and each region has its own distinctive styles and types <strong>of</strong><br />

crafts. In <strong>the</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>ast Her Majesty admired <strong>the</strong> hand-woven<br />

fabrics, and encouraged <strong>the</strong> women to weave material for<br />

sale. Silkworm projects were set up and Her Majesty supplied<br />

looms and weaving material as well as equipment and<br />

supplies needed for o<strong>the</strong>r crafts. A market was guaranteed at<br />

fair prices, and <strong>of</strong>ten, when <strong>the</strong> need was great, payment was<br />

made in advance. In <strong>the</strong> South <strong>the</strong> old craft <strong>of</strong> Yan Lipao vine<br />

weaving was revived and expanded. In many cases all it<br />

took to make an item popular was to have Her Majesty seen<br />

wearing or carrying it.<br />

Once <strong>the</strong>se projects took <strong>of</strong>f <strong>the</strong> financial burden became<br />

too great to be borne alone, so on 26 July 1976 <strong>the</strong><br />

SUPPORT Foundation under Her Majesty's Royal Patronage<br />

was formally established. SUPPORT is <strong>the</strong> acronym for<br />

Supplementary Occupations and Related Techniques. During<br />

its formation period Her Majesty sometimes worked<br />

around <strong>the</strong> clock arranging details, and personally provided<br />

a substantial amount <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> "seed money" to get it started. In<br />

<strong>the</strong> sixteen years <strong>of</strong> its existence <strong>the</strong> SUPPORT Foundation<br />

has grown like a wild banyan tree with its limbs and branches<br />

covering and protecting wide areas. Expanded far beyond<br />

Mudmee silk and Yan Lipao handbags, crafts now include<br />

lea<strong>the</strong>r carving, pottery making, mat weaving, and many<br />

o<strong>the</strong>rs.<br />

While <strong>the</strong> workers-young and old, male and female,<br />

physically sound or disabled alike-have benefited financially<br />

and pridefully from <strong>the</strong>ir work, <strong>the</strong> nation has also benefited<br />

by <strong>the</strong> preservation or relearning <strong>of</strong> many old indigenous arts<br />

and crafts. A few <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se, one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m kram, were so nearly<br />

lost that Her Majesty asked elderly retired craftsmen to come<br />

to teach at <strong>the</strong> SUPPORT schools.<br />

Her Majesty Queen Sirikit has a rare eye for seeing<br />

beauty in <strong>the</strong> simple things <strong>of</strong> life that many never notice at<br />

all or take for granted; an odd-shaped basket may become a<br />

design for pottery, or a certain kind <strong>of</strong> short-lived beetle with<br />

its iridescent colors can become a brooch or be used in o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

decorative ways. Queen Sirikit has said, "Before urging <strong>the</strong><br />

villagers to make anything we must be certain that <strong>the</strong><br />

products will be marketable, not for charity alone .... We must<br />

put <strong>the</strong>m on <strong>the</strong>ir way so <strong>the</strong>y can stand on <strong>the</strong>ir own feet."<br />

<strong>The</strong> interests <strong>of</strong> H.M. Queen Sirikit are limitless-not<br />

only for people, but for wildlife conservation, reforestation<br />

and preservation <strong>of</strong> precious watersheds, and sustainable use<br />

<strong>of</strong> natural resources, for <strong>the</strong>y balance life. Her Majesty is<br />

President <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Thai Red Cross <strong>Society</strong> and grants her Royal<br />

Patronage to many worthy charities. Her life might be<br />

compared to a well-cut diamond; each facet reflects <strong>the</strong><br />

compassionate care and interest <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Queen in her country,<br />

its culture and history, and <strong>the</strong> lives and well-being <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Thai people.<br />

Her Majesty Queen Sirikit honored <strong>The</strong> <strong>Siam</strong> <strong>Society</strong><br />

many years ago by graciously consenting to become a Vice<br />

Patron <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Society</strong>. <strong>The</strong> President, Council and membership<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Siam</strong> <strong>Society</strong> proudly join toge<strong>the</strong>r in wishing<br />

Her Majesty good health and a long and happy life on her<br />

auspicious 60th (Fifth Cycle) birthday.

SECTION II<br />

PEOPLE AND EVENTS

A GREAT HONOR FOR THE SIAM SOCIETY<br />

His Royal Highness Crown Prince Maha Vajiralongkorn became a Vice-Patron <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Siam</strong> <strong>Society</strong> on 23 December<br />

<strong>1992</strong>. On 25 December he represented His Majesty <strong>the</strong> King at <strong>the</strong> Gold-Casting Ceremony for <strong>the</strong> <strong>Siam</strong> <strong>Society</strong>'s Buddha<br />

Footprint Project in honor <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Fifth Cycle Birthday <strong>of</strong> Her Majesty Queen Sirikit. <strong>The</strong> ritual was presided over by His<br />

Holiness Somdet Phra Nyanasamvara, <strong>the</strong> Supreme Patriarch, at Wat Bovornives Vihara. <strong>The</strong> gold ca kra as cast is shown in<br />

<strong>the</strong> inset. (Above)<br />

His Excellency Air Chief Marshal Siddhi Savetsila, Member <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Privy Council and Acting Chairman <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Organizing<br />

Committee, participated in <strong>the</strong> ceremony along with many palace and government <strong>of</strong>ficials. Principal donors and members<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Council were also in attendance, led by Dr. Piriya Krairiksh, President <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Siam</strong> <strong>Society</strong>. Among <strong>the</strong> members<br />

attending was Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Emmanuel Guillon from Paris and Madame. (Below) Photographs by Dacho Buranabunpot.

HONORS TO DISTINGUISHED PERSONS<br />

Dr. Tem Smitinand was<br />

awarded <strong>the</strong> position <strong>of</strong> Honorary<br />

Member <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Siam</strong> <strong>Society</strong> at <strong>the</strong><br />

Annual General Meeting <strong>of</strong> <strong>1992</strong> in<br />

recognition <strong>of</strong> his distinguished service<br />

for many years, which included terms<br />

as Vice President, Leader <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Natural<br />

History Section, and Honorary Editor<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Natural History Bulletin.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world's leading experts in<br />

<strong>the</strong> fi elds <strong>of</strong> forestry and botany in<br />

general, he has been a member <strong>of</strong> numerous<br />

learned organiza ti ons and is<br />

<strong>the</strong> author <strong>of</strong> many important books<br />

and articles.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Siam</strong> <strong>Society</strong> announces<br />

with pride tha t H.E. Mr. A nand<br />

Panyarachun, twice Prime Minister <strong>of</strong><br />

Thailand, has become an Honorary<br />

Member. Mr. Anand Panyarachun is<br />

<strong>the</strong> first prime minister to address <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Society</strong> while in <strong>of</strong>fice.<br />

Mr. Dacre F.A. Raikes, O.B.E.,<br />

Vice President <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Siam</strong> <strong>Society</strong>, was<br />

similarly awarded <strong>the</strong> position <strong>of</strong> Honorary<br />

Member by <strong>the</strong> Council and<br />

Members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Society</strong> at <strong>the</strong> same<br />

Annual General Meeting. During <strong>the</strong><br />

decades <strong>of</strong> his varied outstanding activities<br />

in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Society</strong>, Mr. Raikes has<br />

perhaps been best known for his promotion<br />

<strong>of</strong> Thai music as <strong>the</strong> organizer<br />

and leader <strong>of</strong> troupes <strong>of</strong> classical musicians<br />

from Srinakharin Viroj University<br />

on visits to Britain, continental<br />

Europe and <strong>the</strong> United States. (Photogra<br />

ph by Virgi nia Di Crocco.)<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Siam</strong> <strong>Society</strong> announces<br />

wi th pleasure <strong>the</strong> appointment <strong>of</strong><br />

Mr. Jan J. Boeles, Life Member <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Society</strong> and well-known scholar <strong>of</strong> Thai<br />

history, as Honorary Advisor on Art<br />

History and Archaeology in Sou<strong>the</strong>ast<br />

Asia fo r <strong>the</strong> Faculty <strong>of</strong> Arts, <strong>the</strong> State<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Leiden. Mr. Boeles was<br />

formerly Director <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Siam</strong> <strong>Society</strong><br />

Research Center and is <strong>the</strong> author <strong>of</strong><br />

numerous scholarly works contributing<br />

to a better understanding <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Thai<br />

past. (Photograph by Virgi nia Di Crocco.)

THE SIAM SOCIETY CEMENTS TIES<br />

WITH THE MALAYSIAN BRANCH OF THE<br />

ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY<br />

At <strong>the</strong> kind invita tion<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Malaysian Branch <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Royal Asiatic <strong>Society</strong>, <strong>the</strong> President<br />

and fourteen Members <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Siam</strong> <strong>Society</strong> visited <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

Malaysian counterparts in August<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>1992</strong>, visiting cultural<br />

sites and monuments under <strong>the</strong><br />

guidance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir most hospitabl<br />

e hosts . Here Dr. Piriya<br />

Krairiksh, President <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Siam</strong><br />

<strong>Society</strong> (fifth left), meets with<br />

H is H ig hness Raja M u da,<br />

Crown Prince <strong>of</strong> Selangor (in<br />

fro nt <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> column) and Dr.<br />

Dato' Khoo Kay Kim, President<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Malaysian Branch <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Royal Asiatic <strong>Society</strong> (fou rth<br />

left) toge<strong>the</strong>r with <strong>of</strong>ficers and<br />

members <strong>of</strong> both societies. His<br />

Highness Raja Muda was <strong>the</strong><br />

gracious host at a gala dinner<br />

for both groups.<br />

Dr. Piriya Krair iksh<br />

and Tan Sri Dato' Dr. Mubin<br />

Sheppard, Senior Vice President<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Malaysian Branch <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Royal Asiatic Socie ty a nd<br />

Honorary Editor <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> MBRAS<br />

<strong>Journal</strong>, exchange views on aspects<br />

<strong>of</strong> Thai and Malaysian<br />

culture.

SECTION III<br />

A CONTEMPORARY LETTER<br />

ABOUT THE EVENTS OF 1688

Mrs. Boonkrong Indhusophon<br />

(Photograph by Noppadol Suwanveerakorn )<br />

This issue <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> journnl <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sinm <strong>Society</strong> bas been made possible by <strong>the</strong> most kind generosity <strong>of</strong><br />

Mrs. Boonkrong Indhusophon, Life Member. This special tribute by <strong>the</strong> JSS to Her Majesty <strong>the</strong> Queen in<br />

honor <strong>of</strong> her Fifth Cycle Birthday fea tures <strong>the</strong> first publica tion anywhere <strong>of</strong> a contemporary letter about <strong>the</strong><br />

Crisis <strong>of</strong> 1688 in <strong>Siam</strong> from <strong>the</strong> collection <strong>of</strong> Mrs. Boonkrong's late husband, Mr. Prakaipet Indhusophon.<br />

Mr. Prakaipet was Thailand's most renowned philatelist and one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most distinguished and honored in<br />

<strong>the</strong> world. <strong>The</strong> letter that Mrs. Boonkrong has made available to <strong>the</strong> JSS sets <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>me for <strong>the</strong> articles in<br />

this issue. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Siam</strong> <strong>Society</strong> Under Royal Pa tronage and <strong>the</strong> JSS join in expressing <strong>the</strong>ir warmest thanks<br />

to Mrs. Boonkrong, who in memory <strong>of</strong> her distinguished husband and in her own right continues to hold<br />

<strong>the</strong> Thai flag high at philatelic ga <strong>the</strong>rings world wide.

Mr. Prakaipet lndhusophon

PRAKAIPET INDHUSOPHON<br />

BONNIE DAVIS<br />

MEMBER OF THE COUNCIL<br />

THE SIAM SOCIETY<br />

With <strong>the</strong> premature death <strong>of</strong> Prakaipet Indhusophon<br />

in April, 1991, Thailand lost perhaps <strong>the</strong> greatest philatelist<br />

she has ever claimed as her own. <strong>The</strong>re are many stamp<br />

collectors among Thai people but far fewer philatelists. Until<br />

"Pet" began making his genial presence known at international<br />

shows, foreigners totally dominated <strong>the</strong> scene <strong>of</strong> Thai<br />

stamp collecting exhibits outside <strong>of</strong> Thailand.<br />

Stamp collections have been described as "bits <strong>of</strong><br />

colored paper having little or no use beyond post <strong>of</strong>fini·doors."<br />

In 1840, when <strong>the</strong> handset stamps <strong>of</strong> England were first seen,<br />

<strong>the</strong>y were derided as "bits <strong>of</strong> paper with glutinous wash at<br />

<strong>the</strong> back."<br />

A Frenchman, Georges Herpin, is credited with originating<br />

<strong>the</strong> word philately. In his Le collectionneur de timbrespaste<br />

published in 1864 he combined two words from <strong>the</strong><br />

Greek language, philo (love <strong>of</strong>) and ateles (free from payment).<br />

<strong>The</strong> latter word was accepted as equivalent to "free" or franco,<br />

as had formerly been stamped on pre-paid letters.<br />

Prakaipet was a man who stood out in any groupand<br />

Pet never stood alone. He was a gregarious gentleman<br />

who not only volunteered himself-he volunteered o<strong>the</strong>rs as<br />

well. Several times I received unexpected letters from editors<br />

<strong>of</strong> stamp journals in o<strong>the</strong>r countries asking <strong>the</strong> whereabouts<br />

<strong>of</strong> a promised article; only after calling Pet would I learn he<br />

had once again promised an article from me for <strong>the</strong> journal<br />

and had <strong>the</strong>n forgotten to tell me. After knowing him for<br />

close to a decade, it became almost routine and <strong>the</strong>re was<br />

nothing for it but to get busy and produce <strong>the</strong> promised article<br />

as quickly as possible! It was impossible to refuse Pet.<br />

Try telling him you hadn't planned to attend a meeting, or<br />

whatever-he was charming but persistent in telling you that<br />

his car and driver were on <strong>the</strong>ir way to pick you up.<br />

Prakaipet Indhusophon was born on 16 January 1929<br />

to Nai Chamnan and Mrs. Kian lndhusophon. His fa<strong>the</strong>r was<br />

a former Under Secretary <strong>of</strong> State, Ministry <strong>of</strong> Communications.<br />

Prakaipet served in <strong>the</strong> military service as a Squadron<br />

Leader in <strong>the</strong> Royal Thai Air Force. He also served <strong>the</strong> country<br />

as a Deputy Minister <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Ministry <strong>of</strong> Industry, and as<br />

Secretary General to former Prime Minister M.R. Kukrit<br />

Pramoj.<br />

Pet began collecting stamps when he was about ten<br />

years old and continued throughout his school and university<br />

years. It was not until 1979, however, that he became<br />

an active member <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Philatelic Association <strong>of</strong> Thailand<br />

(PAT). He became President <strong>of</strong> PAT in 1984 and remained<br />

so until his untimely death.<br />

In 1981 he exhibited in an international stamp exhibition<br />

for <strong>the</strong> first time, at PHILATokyo in Japan. At Thailand's<br />

first international stamp exhibition in August, 1983,<br />

held to commemorate <strong>the</strong> centenary <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Royal <strong>Siam</strong>ese<br />

Postal Service, Pet's exhibit won <strong>the</strong> Grand Prix. <strong>The</strong> Grand<br />

Prix d'Honneur was awarded for his exhibit entitled <strong>Siam</strong> 19th<br />

Century and <strong>Siam</strong>ese Post Offices Abroad at <strong>the</strong> international<br />

exhibition in India in January 1989. This is <strong>the</strong> most prestigious<br />

<strong>of</strong> all awards in philatelic competitive exhibits and Pet<br />

was <strong>the</strong> first Thai ever to achieve this honor. Following this<br />

award he was invited to attend <strong>the</strong> World Stamp Expo 1989<br />

in Washington, D.C. toge<strong>the</strong>r with o<strong>the</strong>r World Grand Prix<br />

awardees.<br />

In March 1989 Pet was invited by <strong>the</strong> British Philatelic<br />

Federation Limited to sign <strong>the</strong> Roll <strong>of</strong> Distinguished Philatelists,<br />

regarded internationally as <strong>the</strong> world's pre-eminent<br />

philatelic honor. Pet was <strong>the</strong> first Thai elected to sign <strong>the</strong> roll.<br />

Initiated at <strong>the</strong> Philatelic Congress <strong>of</strong> Great Britain in 1920, it<br />

had as its first signator King George V in 1921, followed by<br />

thirty-nine o<strong>the</strong>r leading philatelists <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world at that time.<br />

Since its inception a few over 221 philatelists have been elected.<br />

Stamp collecting, or philately, to use <strong>the</strong> more elegant<br />

term, is governed by <strong>the</strong> 66-year-old Federation Internationale<br />

de Philatelie (FIP). It is this body which oversees <strong>the</strong> organization<br />

<strong>of</strong> international stamp exhibitions in <strong>the</strong> more than one<br />

hundred member countries. <strong>The</strong> rules are strict-not only on<br />

what can or cannot be shown in an international exhibition,<br />

but also how items are displayed and described. Only recently<br />

revenue (tax) stamps have been accepted as being a<br />

legitimate part <strong>of</strong> philately, but unfortunately none <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>

22<br />

Mao Zedong and Mr. Prakaipet exchange greetings as Prime Minister M.R.<br />

Kukrit Pramoj looks on.<br />

Mr. Prakaipet signs <strong>the</strong> Roll <strong>of</strong> Distinguished Philatelists in March 1989 at<br />

<strong>the</strong> in vitation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> British Philatelic Federation with Mrs. Boonkrong at his side.

23<br />

rules as to size <strong>of</strong> exhibition sheets and numbers shown in a<br />

frame have been adapted to <strong>the</strong> special needs <strong>of</strong> revenue<br />

collecting. Before his d ea th, however, Pet was quick to get a<br />

representative from Thailand accepted by <strong>the</strong> revenue committee.<br />

In his voluntary work to promote stamp collecting<br />

throughout <strong>the</strong> Asian region, Pet was always on <strong>the</strong> go. He<br />

regularly attended meetings <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Inter-Asia Philatelic Federation<br />

(FlAP), and exhibited, judged, or served as country<br />

commissioner in shows from Singapore to India to Australia.<br />

Pet undoubtedly did more for Thai philately, both at home<br />

and abroad, than any o<strong>the</strong>r collector ever has. O<strong>the</strong>rs have<br />

won awards, become well known and had grand, awardwinning<br />

collections, but none <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m was Thai. Pet proudly<br />

collected and represented his own country as an "Ambassador<br />

with Stamps" for Thailand.<br />

Pet is also to be applauded and remembered for<br />

bringing back to Thailand many things <strong>of</strong> national and historical<br />

value including royal letters and letters written by o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

personalities who fi gure in Thai history such as John Bush<br />

and Dr. Dan Bradley, and <strong>the</strong> letter about <strong>the</strong> Revolution in<br />

<strong>Siam</strong> <strong>of</strong> 1688 featured in this issue <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> JSS. For that fact<br />

alone, a part from his many awards, Khun Prakaipet<br />

Indhusophon deserved high praise and recognition. This<br />

praise can now deservedly be passed to Khun Boonkrong<br />

Indhusophon, Pet's charming wife. Khun "Ad" has kept <strong>the</strong><br />

now famous collection intact and has herself taken <strong>the</strong> exhibit,<br />

by invitation, to several international exhibitions since Pet's<br />

death.<br />

To Pet philately was more than a hobby; it became a<br />

mission he served with dedication. Collectors who knew him,<br />

miss him. I sometimes even miss <strong>the</strong> letters from disgruntled<br />

editors telling me that once again, Pet had "volunteered" my<br />

services and forgotten to tell me.<br />

Mr. Prakaipet with a galaxy <strong>of</strong> top-ranking leaders <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> People's Republic <strong>of</strong> China and Thailand at <strong>the</strong> time <strong>of</strong> Prime<br />

Minister M.R. Kukrit Pramoj's visit to China in 1975. Mr. Prakaipet is fourth from <strong>the</strong> left in <strong>the</strong> second row, behind and to<br />

<strong>the</strong> left <strong>of</strong> M.R. Kukrit (fifth from <strong>the</strong> left, first row), and just to <strong>the</strong> right <strong>of</strong> ACM Siddhi Savetsila. Three prime ministers <strong>of</strong><br />

Thailand appear in this photograph : Maj Gen. M.R. Kukrit, Gen. Chatichai Choonhavan (fourth from <strong>the</strong> right, first row), and<br />

Mr. Anand Panyarachun (second from <strong>the</strong> right, first row). O<strong>the</strong>rs among <strong>the</strong> luminaries are Deng Xiaoping, (to <strong>the</strong> left <strong>of</strong> M.R.<br />

Kukrit), Mr. Amnuay Viravan (third from <strong>the</strong> left, first row), and Zhou Enlai (to <strong>the</strong> right <strong>of</strong> M.R. Kukrit).

A CONTEMPORARY LETTER<br />

BY AN ENGLISH MERCHANT<br />

ABOUT THE CRISIS<br />

IN SIAM, 1688<br />

Mr. William Soame, evidently a merchant attached to <strong>the</strong> British East India Company, sent a letter<br />

on 20 December 1688 to "some friend" at Madras in which he described <strong>the</strong> recent "Revolution <strong>of</strong> <strong>Siam</strong>": <strong>the</strong><br />

intrigues surrounding <strong>the</strong> death <strong>of</strong> King Narai, <strong>the</strong> execution <strong>of</strong> Constance Phaulkon, <strong>the</strong> accession to <strong>the</strong><br />

throne <strong>of</strong> Phetracha, and <strong>the</strong> turbulence surrounding <strong>the</strong> French military presence in <strong>Siam</strong>. All <strong>the</strong>se events<br />

had occurred between May and October <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Same year. Soame writes not as an eyewitness, but as one<br />

who has composed for <strong>the</strong> record "such an Imperfect Account as has been collected from such informations<br />

as in [his] judgement appeared most credible." So far as is known his account has never before been<br />

published.<br />

<strong>The</strong> letter forms part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> collection <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> late Mr. Prakaipet lndhusophon, Thailand's premier<br />

philatelist and one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most prominent in <strong>the</strong> world. It has been made available to <strong>the</strong> JSS though <strong>the</strong><br />

kindness <strong>of</strong> his widow, Mrs. Boonkrong Indhusophon, who has so kindly sponsored this issue.<br />

Mrs. Boonkrong informs us that she first saw <strong>the</strong> letter some ten years ago in <strong>the</strong> collection <strong>of</strong> a<br />

friend in Singapore. It was later sold to a Thai collector, Mr. Anatchai Rattakul, who in turn sold it to an<br />

auction house in England, from which Mr. Prakaipet acquired it. It was translated into Thai by Dr. Usanee<br />

Laothamatat, presumably for its first Thai owner.<br />

<strong>The</strong> letter, browned with age, is seven pages long and is written on both sides <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sheets, which<br />

measure 20 x 30 em. <strong>The</strong> ink has seeped through, which adds to <strong>the</strong> difficulty in reading it. It was<br />

transcribed first in 1991 by Mr. Martin E. Hardy, Assistant Director, Western Hemisphere Department,<br />

International Monetary Fund, Washington, D.C., and has been reexamined by <strong>the</strong> Honorary Editor and Mrs.<br />

Virginia M. Di Crocco.<br />

<strong>The</strong> text is presented here both in modern script, with <strong>the</strong> punctuation and spelling <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> original<br />

preserved, and in facsimile. (Photographs by Noppadol Suwanveerakorn.)<br />

Worshippfull sir<br />

Malaca 20th December 1688<br />

You may probably before this have understood <strong>the</strong><br />

Revolution <strong>of</strong> <strong>Siam</strong> from those more advantagiously Qualified<br />

to Informe - never<strong>the</strong>less such an Imperfect Account as hath<br />

been collected from such Informations as in my judgement<br />

appeared most credible, Please to take as followeth.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Beginning <strong>of</strong> March <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>n King being Disabled<br />

to <strong>the</strong> affairs <strong>of</strong> Gouvernment was pleased to appoint and<br />

Impower for Officiating Royall Authoritye Upra Pipera Chai<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Siam</strong> Genal!. Frape [Phra Pi] his adopted son, & Oya<br />

Phaulkon, <strong>the</strong> Princess Daughter to be made accquainted with<br />

and consenting to all <strong>the</strong>ir Proceedings. <strong>The</strong> .2. Princes His<br />

Bro<strong>the</strong>rs (and according to <strong>the</strong>ir Law, Heirs to <strong>the</strong> Crowne)<br />

<strong>the</strong> iLegitimate Son had been particularly and most Effectually<br />

excluded as may be perceived by <strong>the</strong> Sequell.<br />

<strong>The</strong> thus Excludeing <strong>the</strong> Royall Line wholely consisting<br />

in <strong>the</strong> Disinhereited Princes highly favoured and<br />

Incourriged <strong>the</strong> aspirement <strong>of</strong> Both <strong>Part</strong>yes yt. designed<br />

<strong>the</strong>mselves Candidates for <strong>the</strong> Crowne. <strong>The</strong> King's Illness<br />

increasing to past Hopes ( or ra<strong>the</strong>r Feares <strong>of</strong> Recoverye )<br />

Each <strong>Part</strong>ye drawes His Friends to Court, and Forces to adjacent<br />

villages. And Oya Phaulkon with Consent <strong>of</strong> Councell,<br />

Regent in <strong>the</strong> Kings Name Required <strong>the</strong> French Genall. with<br />

a Certaine Number <strong>of</strong> his Souldiers to Repair to Levo, Who<br />

by <strong>the</strong> waye touching att <strong>Siam</strong>, <strong>the</strong>n received Such advices<br />

from <strong>the</strong> French Bishopp, as caused His Return to Bancocke,<br />

Excusing itt to <strong>the</strong> Oya Phaulkon on account <strong>of</strong> a Rumor <strong>the</strong>n<br />

generally Credited, <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Kings being Dead, Both <strong>Part</strong>yes in<br />

this Councell Regent concurr'd in having a <strong>Part</strong>ye <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> French<br />

Soldiers up to Court, <strong>The</strong> one to be streng<strong>the</strong>ned by <strong>the</strong>ire<br />

Assistance, <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r by Separateing <strong>the</strong> Force to Facilitate<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir Destruction. Wherefore a Second Requiry was made in<br />

Complyance wherewith <strong>the</strong> Genall. only accompanied with

25<br />

his Eldest Son makes his appearance, whose comeing in that<br />

Manner and too late for Assistance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Frapian <strong>Part</strong>ye frustrates<br />

<strong>the</strong> designes <strong>of</strong> Both. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Siam</strong> Genall. Upra Pipera<br />

Chai prospering in His designes was by this time ready for<br />

repossession <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir Forts. In order whereunto <strong>the</strong> French<br />

Genallleaveing His two Sons in Hostages was admitted down.<br />

But noe Invitations could ever after Intice Him to Leave His<br />

Fort, till Businesses were Honourably accommodated for His<br />

departing <strong>the</strong> Kingdome.<br />

About <strong>the</strong> 10th <strong>of</strong> May Frape <strong>the</strong> Adopted Son was by<br />

procurement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Siam</strong> Generall Upra Pipera Chai cutt to<br />

pieces in <strong>the</strong> Pallace In whose Scrutore [=escritoire] was found<br />

a paper with names <strong>of</strong> a <strong>Part</strong>ye <strong>of</strong> Mandereens, wherein upon<br />

<strong>the</strong> Kings Decease <strong>the</strong> Crowne was allotted to Frape <strong>the</strong><br />

Adopted Son, <strong>the</strong> chief Princedom to Oya Phaulkon, and<br />

<strong>of</strong>fices <strong>of</strong> State how to be disposed. <strong>The</strong> Genall. Upra Pipra<br />

Chai haveing as yett Seemingly favoured <strong>the</strong> Succession <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Royal Line was hereby Sufficently - fortified in proovening<br />

treasonable Designes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Frapean <strong>Part</strong>ye and <strong>the</strong>reuppon<br />

Oya Phaulkon Sent for to answere <strong>the</strong> Charge, was uppon<br />

Entering <strong>the</strong> Palace being Seized, Narrowly Scaped Execution,<br />

wch. for Some reasons <strong>of</strong> State was Reprieved till <strong>the</strong><br />

25th. att Night when in His Irons, and after <strong>the</strong> Manner <strong>of</strong> a<br />

Common Malefactor He was carryed to Execution without<br />

that Gate <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Citye bearing ye. Regent Upra's Name. A<br />

Padre for Confession with o<strong>the</strong>r Requests being denyed, His<br />

Speech in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Siam</strong> Language ( avouching that Loyaltie to<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir King was <strong>the</strong> Cause <strong>of</strong> his Suffering ) concluded riseing<br />

up from Devotion, tooke <strong>of</strong> His Relicaro Consacrado given by<br />

<strong>the</strong> Pope containeing pieces <strong>of</strong> Bones <strong>of</strong> Severall reputed<br />

Roman Saints, and desired it might be given to one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Christian Padress, but happened to John Spens out <strong>of</strong> whose<br />

Hands <strong>the</strong> Devonionists have not yett obtained itt by a<br />

Purchaseing Consideration. Thus while Standeing, <strong>the</strong> Executioner<br />

att one Stroke Severed <strong>the</strong> Head, <strong>the</strong> Body falling<br />

was cutt into two, and with <strong>the</strong> Corps <strong>of</strong> His yong Son John,<br />

(who had <strong>the</strong>n Layne in State in <strong>the</strong> Chapell about .4. Months<br />

in a C<strong>of</strong>fin <strong>of</strong> Sylver within one <strong>of</strong> wood ) was putt into a<br />

Hole neare <strong>the</strong> place <strong>of</strong> Execution. where it may be Supposed<br />

to Remayne without any Remarkable Demonstration.<br />

As to <strong>the</strong> Suffering <strong>of</strong> His Lady few <strong>Part</strong>iculars have<br />

come to our Knowledge Save yt. her Selfe, and her Fa<strong>the</strong>rs<br />

Familie have been deprived <strong>of</strong> all yt by a Scrutinous Search<br />

assisted with Corporal Tortures for Confession could possibly<br />

be found.<br />

<strong>The</strong> .2. Princes by means <strong>of</strong> Severe chastisements from<br />

<strong>the</strong> King <strong>the</strong>ir Bro<strong>the</strong>r, haveing as was reported threatened<br />

Revenge uppon His Corps, which being made Knowne. His<br />

Matie. was onely prevailed with to Reprieve <strong>the</strong>ir Executions<br />

till <strong>the</strong> time <strong>of</strong> His Decease Should draw neare, wch. now<br />

happening, <strong>the</strong> Regent Upra on <strong>the</strong> 28th. June at Night, loyally<br />

caused <strong>the</strong>m to be Stampt to death with Sandal Wood,<br />

and His Matie. expiring <strong>the</strong> 30th. about 8th. att Night <strong>the</strong> Said<br />

Regent Upra usurpd <strong>the</strong> Royalty to Himselve and His Familie.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Hurly Burly att Court beginning Now to appease<br />

and dye <strong>of</strong> fortune Cast, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Siam</strong>ese betake <strong>the</strong>mselves by<br />

Force <strong>of</strong> Armes to Recover Posession <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir Forts, but not<br />

prevaileing, in Some time a Cessation <strong>of</strong> Armes was agreed<br />

during wch. Intervall <strong>the</strong> French fitt out a Sloop for Information<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir Shipping, expectant <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>n approaching<br />

Monsoon, wch. grounding in <strong>the</strong> River was overpowered and<br />

Boarded by <strong>the</strong> Ennemy, whereupon one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Soldiers with<br />

Himselve as is Reported, blew up about 200 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m. After<br />

wch. a Peace was concluded, Shipps, Provisions &c given for<br />

Transportation and with much difficultye Permission obtained<br />

for Captain Williams, Captain Howell, & a Certain Number<br />

<strong>of</strong> English Sailors to assist <strong>the</strong> Navigation<br />

About <strong>the</strong> 25th. September <strong>the</strong> Lady Phaulkon with<br />

Her Son assisted by <strong>the</strong> Jesuites <strong>of</strong> her late Husbands<br />

Canonicall Privy Councell made Her escape to Bancoke wch.<br />

putt a Stopp to all proceedings Save <strong>the</strong> Reneweing <strong>of</strong> Hostile<br />

Preparations. <strong>The</strong> French Genall. and Councell <strong>of</strong> Warrfinding,<br />

as may be Supposed, that <strong>the</strong>ir Honble. come <strong>of</strong>f was<br />

like to be obstructed & <strong>the</strong> Christian Interest in that Kingdome<br />

more Severely- persecuted Solely uppon Account <strong>of</strong><br />

detaineing <strong>the</strong> Distressed Lady and Son, did after 12 Dayes<br />

Consultations consent to termes <strong>of</strong> Surrender, wch. <strong>the</strong> 8th <strong>of</strong><br />

October was done accordingly.<br />

October <strong>the</strong> 23th [sic] <strong>the</strong> French with <strong>the</strong>ir two <strong>Siam</strong><br />

Hostages marched on Board <strong>the</strong>ir Shipps 30 and odd pieces<br />

<strong>of</strong> Ordnance---. & with Some Soldiers in Boates, Looseing<br />

Companye with <strong>the</strong> Shipps in <strong>the</strong> Night were intercepted<br />

wch. occasioned <strong>the</strong> Hostages on both Sides to be detained<br />

Save <strong>the</strong> French Chief & Generalls younger Son comeing neare<br />

<strong>the</strong> Shipps, forced or frightened <strong>the</strong>ir Guard Mandereen to<br />

carry <strong>the</strong>m on Board. Soe yt. <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> French Hostages <strong>the</strong> Bishop<br />

only is remaineing.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Genall. after about .3. dayes Stay att <strong>the</strong> Barr, Sent<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Siam</strong>ers word, yt He would Stay Six dayes longer att <strong>the</strong><br />

Duch Hand Expecteing <strong>the</strong> intercepted Boats, but noe answer<br />

comeing in that time, <strong>the</strong> 3d. November He Sett Saile.<br />

July <strong>the</strong> 4th. Mr. Joseph Baspoole was Seized, Fetter'd,<br />

and Imprisoned, whose treatment to extort Confessions<br />

concerning <strong>the</strong> late Lord Phaulkon's Estate hath not been free<br />

from Corporall tortures.<br />

Mr. Hodges <strong>the</strong> Honble. Companye Commr. happening<br />

to be at Levo, in <strong>the</strong> time <strong>of</strong> Revolution was Seized,<br />

Plundered, Gongoed, chained, an fettered for ,Severall dayes<br />

and Nights in <strong>the</strong> Lucombands [= Thai ~'1ln1uu riiakampan,<br />

ships] and for <strong>the</strong> more Honble. advancement in Degrees <strong>of</strong><br />

that Universitye, admitted a Fellow Commoner <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Daily<br />

Relicks <strong>of</strong> His Keepers Rice. till <strong>the</strong> Councell takeing into<br />

Consideration His particular Circumstances were pleased to<br />

order His Releasement, after wch. <strong>the</strong> 31st. July <strong>the</strong> Said<br />

Mr. Hodges wayted on Mumpann, late Ambassador to France<br />

being <strong>the</strong> first day <strong>of</strong> Publick appearance in His <strong>of</strong>fice as<br />

Barcalong who expresst Himselve to this effect.<br />

To you <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> English Nation I Shall Speak in Genall.<br />

and first as to <strong>the</strong> Business <strong>of</strong> Fenasire. [Tenasserim] yr. people<br />

were in fault, and ours not without. But <strong>the</strong> things yt.<br />

<strong>the</strong>re happned cannot be recalled.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Late King was pleased Some years agoe to take<br />

into Favour and putt into great Employments Mr. Constant<br />

Phaulkon, who for great Crimes has received His Chastise-

26<br />

ment But for time to come, if <strong>the</strong> English are Inclined to have<br />

a Trade with us according to <strong>the</strong> Customes and Privilidges<br />

formerly granted <strong>the</strong>y shall be welcome to itt. Out Friend at<br />

Mergen according to <strong>the</strong> advices yt arrived 2 dayes before I<br />

left Syam, have been very Severely dealt- with. wch. Extraordinary<br />

Severity, as is believed, hath occasioned<br />

Mr. Threders Death.<br />

We expect to follow this Conveyance in 8. or 10 dayes<br />

after wch. in due time I hope to have <strong>the</strong> Honr. <strong>of</strong> Seeing you<br />

in good Health att Madrass being what <strong>of</strong>ferrs at present from<br />

Yr. oblidged Humble<br />

Servant to Command<br />

William Soame<br />

[Written on <strong>the</strong> back <strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> folds <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> letter:]<br />

Malacca 20 Decbr 1688<br />

From Mr.Soame<br />

to some freind in<br />

India about <strong>the</strong><br />

Revolution at Syam.

27<br />

28<br />

,<br />

. q<br />

;:?:. -' ./ ,. .,.<br />

/ ,.<br />

/<br />

"'· c. ~<br />

c_,<br />

/;~ )/.

29<br />

·h ~ .....<br />

"1<br />

r,.~<br />

~<br />

h i. ,'l<br />

--~<br />

1.(..~<br />

/1<br />

('.- (, . / ,<br />

• '<br />

/<br />

'<br />

,<br />

~ .-""' -};; ...... d,.._,'<br />

1•••-;r ·~·<br />

/<br />

; . • .A{..,.

30<br />

,4<br />

"<br />

l'· ,<br />

·'1':<br />

.,.<br />

•<br />

I~ '-....<br />

, ...<br />

/<br />

,<br />

'<br />

31<br />

. -

32<br />

/"'<br />

l.--. .. ,~ ...... - /<br />

~,.. - ~ ~ .<br />

'?<br />

/<br />

...,.<br />

-{ /<br />

~n/r·

SECTION IV<br />

AYUDHYA ARCHITECTURE

36<br />

0<br />

fi<br />

CJl

A REVISED DATING OF AYUDHYA<br />

ARCHITECTURE<br />

PIRIYA KRAIRIKSH<br />

PRESIDENT OF THE SIAM SOCIETY<br />

At <strong>the</strong> beginning <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> essay on '<strong>The</strong> History <strong>of</strong> <strong>Siam</strong><br />

before <strong>the</strong> Founding <strong>of</strong> Ayudhya," which is included in his<br />

introduction to <strong>the</strong> Royal Autograph Recension <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Annals <strong>of</strong><br />

Ayudhya published in 1914, Prince Damrong Rajanubhab<br />

wrote:<br />

"<strong>The</strong> books composed by <strong>the</strong> old writers sometimes<br />

contain stories <strong>of</strong> too miraculous a kind to be believed<br />

at <strong>the</strong> present day; and sometimes different accounts<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> same event are so contradictory that <strong>the</strong> reader<br />

must decide for himself which <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m is right. In<br />

<strong>the</strong> following compilation, <strong>the</strong>refore, <strong>the</strong>re is much<br />

that is conjecture on my part; and as conjecture may<br />

lead to error, <strong>the</strong> reader should use his own powers<br />

<strong>of</strong> discrimination when reading it." 1<br />

This writer agrees with <strong>the</strong> late Mr. Alexander B.<br />

Griswold in his introduction to <strong>the</strong> Second Edition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

English translation <strong>of</strong> Prince Damrong's Tamnan Phuttha Chedi<br />

Sayam (Monuments <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Buddha in Sayam), when he wrote:<br />

"I take this passage to be Prince Damrong's general<br />

advice to future scholars not to regard his conclusions<br />

as <strong>the</strong> final word, but to conduct investigations<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir own. For a long time <strong>the</strong> advice went largely<br />

unheeded in <strong>Siam</strong>: his prestige as a writer was such<br />

that many scholars were content to repeat what he<br />

had said, as if no fur<strong>the</strong>r research could possibly<br />

add anything useful to it. In more recent years,<br />

however, scholars have begun to realize that a better<br />

way to show <strong>the</strong>ir respect for his memory is to<br />

carry on his work, modifying his working hypo<strong>the</strong>ses<br />

when necessary, and searching for fur<strong>the</strong>r information."2<br />

*This article is partially based on a paper entitled "Silpakam<br />

samai Ayudhya thon plai: miti mai thang kansuksa (Art <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> late<br />

Ayudhya period: a new direction in research)" presented to <strong>the</strong> Historical<br />

<strong>Society</strong> Under <strong>the</strong> Royal Patronage <strong>of</strong> Her Royal Highness<br />

Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhom at its meeting at Ayudhya on August<br />

13, <strong>1992</strong>.<br />

<strong>The</strong> aim <strong>of</strong> this paper is to propose a new dating for<br />

Ayudhya architecture which, it is hoped, will replace <strong>the</strong><br />

existing chronology formulated by Prince Damrong in his<br />

Tamnan Phuttha Chedi Sayam (Chronicle <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Monuments <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Buddha in <strong>Siam</strong>), published in 1926. 3 That hypo<strong>the</strong>sis should<br />

now be modified on account <strong>of</strong> misconceptions in its basic<br />

methodology which modern research can point out and rectify,<br />

so that art historical studies can proceed afresh after<br />

having been influenced by <strong>the</strong> hypo<strong>the</strong>sis for sixty-six years.<br />

<strong>The</strong> methodology used in Tamnan Phuttha Chedi Sayam<br />

is based on <strong>the</strong> correlation between existing monuments and<br />

those mentioned in <strong>the</strong> Phra Ratcha Phongsawadan (Royal<br />

Chronicle).<br />

It presupposes that <strong>the</strong> monuments we see today have<br />

remained unchanged since <strong>the</strong> days <strong>the</strong>y were built and that<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir names correspond to those mentioned in <strong>the</strong> chronicles.<br />

Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, it relies on <strong>the</strong> truthfulness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> royal<br />

chronicles without having made a thorough comparison with<br />

foreign sources to verify <strong>the</strong>m. Thus, <strong>the</strong> hypo<strong>the</strong>sis assumes<br />

that <strong>the</strong> monuments existing today were built when <strong>the</strong> royal<br />

chronicles say <strong>the</strong>y were.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se methodological approaches were not challenged<br />

by Pr<strong>of</strong>essor George Coedes, who was Prince Damrong's<br />

research assistant. So great is Prince Darnrong's prestige that<br />

no one has questioned <strong>the</strong> validity <strong>of</strong> his hypo<strong>the</strong>sis. For had<br />

<strong>the</strong> question been raised, his assumptions would have been<br />

found untenable because <strong>the</strong>y are based on premises that lack<br />

valid foundation, and <strong>the</strong> hypo<strong>the</strong>sis would not have been<br />

supported.<br />

It will be shown through comparing <strong>the</strong> monuments<br />

with <strong>the</strong>ir illustrations in 17th and 18th century paintings,<br />

maps and charts, as well as with descriptions by foreign<br />

travellers, that <strong>the</strong> monuments we see today do not correspond<br />

with <strong>the</strong>ir depictions. Also, <strong>the</strong> statements in <strong>the</strong> royal<br />

chronicles regarding <strong>the</strong>ir founding are contradicted by<br />

contemporary Western accounts, which, when cross checked<br />

with 17th and 18th century maps, make it obvious that <strong>the</strong><br />

royal chronicles are usually unreliable.<br />

Prince Darnrong's hypo<strong>the</strong>sis for <strong>the</strong> chronology <strong>of</strong><br />