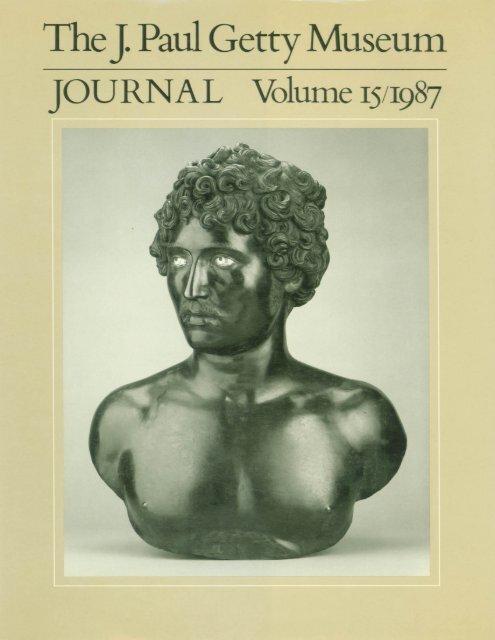

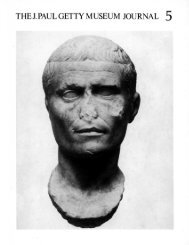

The J. Paul Getty Museum Journal Volume 15 1987

The J. Paul Getty Museum Journal Volume 15 1987

The J. Paul Getty Museum Journal Volume 15 1987

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>The</strong> J. <strong>Paul</strong> <strong>Getty</strong> <strong>Museum</strong>JOURNAL <strong>Volume</strong> <strong>15</strong>/<strong>1987</strong>Including Acquisitions/1986

A Byzantine Pendant in the J. <strong>Paul</strong> <strong>Getty</strong> <strong>Museum</strong>Jeffrey SpierA collection of Greek and Etruscan gems acquired bythe J. <strong>Paul</strong> <strong>Getty</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> in 1981 includes an engravedGraeco-Persian gem set in a gold pendant. <strong>The</strong> entirecollection was published by John Boardman in 1975, 1and the gem in the pendant was described, no doubtcorrectly, as belonging to Boardmans "Bern group" ofthe late fourth century B.C. 2Based upon the engraveddesign on its back, the pendant was classed as Greekand judged to be of early Hellenistic date contemporarywith the gem. 3However, more pendants of this type, aswell as other gold objects of similar style, are known,and their early Byzantine origin can be firmly established.<strong>The</strong> nucleus of the group was originally identifiedby Marvin Ross in his discussion of the examplesin Dumbarton Oaks, 4and others can be added here,including roughly datable examples with reliable provenience.<strong>The</strong>y are as follows:1. Gold pendant set with a Graeco-Persian gem(figs. la-c). H: 2.9 cm (lVs"). Malibu, <strong>The</strong> J. <strong>Paul</strong><strong>Getty</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> 81. AN.76.101. J. Boardman, Intagliosand Rings (London, 1975), no. 101, p. 99, ill.p. 31 (color).2. Gold pendant on gold loop-in-loop chain withopenwork terminals (figs. 2a—b). H (pendant): 3.2cm (l 1 //). New York, <strong>The</strong> Metropolitan <strong>Museum</strong>of Art 17.190.1659. Ex-coll. J. Pierpont Morgan,purchased from Amadeo Canessa, Paris, 1911.Unpublished.3. Gold pendant, inscribed

6 SpierFigures la-c. Left, Pendant set with Graeco-Persian gem. Byzantine, circa sixth century. Gold set with earlier chalcedony scaraboid.Center, back. Right, back. Drawing by Martha Breen Bredemeyer. Malibu, <strong>The</strong> J. <strong>Paul</strong> <strong>Getty</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> 81.AN.76.101.8. Gold pendant found with jewelry and gold coins ofConstans II, Constantine IV, and Tiberius III (fig.8). H: 2.6 cm (1"). Found in Pantalica, Sicily; presentlocation unknown. P. Orsi, Sicilia bizantina(Rome, 1942), vol. 1, no. 7, p. 138, pi. 9.9. Gold disc with engraved cross, perhaps from a pendant(fig. 9). H: 2.1 cm ( 7 /s"). Washington, D.C.,Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection53.12.51. Said to have been found in Constantinople.Ross, D.O. Cat., vol. 2, no. 35, p. 33.10. Silver reliquary pendant with glass cover, relics inside,found with a hoard of gold jewelry. H: 3 cm(l 3 /i6"). Milan, Civico Museo Archeologico. Foundin the excavations at Caesarea Maritima, Israel,1962. Antonio Frova, Scavi di Caesarea Maritima(Milan, 1965), pp. 236-238, figs. 295-297.<strong>The</strong> <strong>Getty</strong> pendant (figs, la—c) is composed of a circularpiece of sheet gold, slightly convex on the back,with the edges folded over the gem on the front side.<strong>The</strong> back is decorated with an engraved circle; withinthis is a pattern of four acanthus leaves arranged so thatthe central unengraved space forms the shape of a cross.Outside the engraved circle is a border of punched dots.A thin, beaded wire is attached along the entire circumferenceof the pendant, and a ridged strip of gold isfolded to form a loop for suspension. <strong>The</strong> gem is achalcedony scaraboid engraved with a running horse,and as noted above, it belongs to a Graeco-Persianworkshop of the late fourth century B.C. Few Byzantineintaglios appear to have been made, and the reuse ofearlier gems in the Byzantine period was not an unusualpractice. Large Graeco-Persian gems were probablyfound frequently, as they are today, and may have beenthought to have magical properties. 5Closest in style to the <strong>Getty</strong> pendant is a fine examplein New York (No. 2, figs. 2a—b) on a gold loop-in-loopchain with round openwork terminals typical of sixthcenturyByzantine work. <strong>The</strong> engraving and patterningare very similar to the <strong>Getty</strong> example, although somewhatmore careful, and the border of punched dots isthe same. A beaded wire is also added to the edge, but itis somewhat thicker than that on the <strong>Getty</strong> pendant.Whatever was set in the pendant is now missing.Another pendant in New York (No. 3; fig. 3) issmaller than No. 2 but is similarly constructed. <strong>The</strong>shape of the engraved cross is slightly different,however, and the common Byzantine cruciform inscriptionc()cbs/£oi)f| (light/life) is added on the cross; this isthe only example among the pendants presently underconsideration to have an inscription. <strong>The</strong> other side ofNo. 3 is undecorated. <strong>The</strong> chain is composed of sixshort loop-in-loop chains joined together with hookson which gems were set; only three of these—an emeraldand two amethysts—survive. <strong>The</strong> gold terminals areheart shaped with filigree openwork. A very similarchain with identical terminals was found with a sixthcenturyByzantine treasure now in Dumbarton Oaks. 6A pendant (No. 4; figs. 4a—b), which was supposedlyfound in Sicily with two gold belt buckles and is now in5. An unpublished Graeco-Persian chalcedony scaraboid in Malibu(85.AN.444.1) was reengraved with magical inscriptions in thethird or fourth century A.D., and another Graeco-Persian scaraboid inOxford bears Koranic texts in Kufic script, which were added in theseventh or eighth century A.D.: See J. Boardman and M.—L. Vollenweider,Catalogue of the Engraved Gems and Finger Rings in the Ashmolean<strong>Museum</strong> (Oxford, 1978), vol. 1, no. 178, and a photo of the backin P. Zazoff, Die antiken Gemmen (Munich, 1983), p. 4, pi. 41.

A Byzantine Pendant 7Figure 2a. Pendant on loop-in-loop chain with openwork terminals. Byzantine,circa sixth century. Gold. H (pendant): 3.2 cm (l 1 //).New York, <strong>The</strong> Metropolitan <strong>Museum</strong> of Art, Gift of J. PierpontMorgan, 17.190.1659. Photo: Courtesy <strong>The</strong> Metropolitan<strong>Museum</strong> of Art, New YorkDumbarton Oaks, is very similar to the others. It is,however, more oval shaped than the previous circularexamples. This pendant again has the border ofpunched dots, and the added beaded wire is thin, likethat of the <strong>Getty</strong> example. It is set with a cameo depictingApollo and Daphne. This may be a rare example ofcontemporary Byzantine glyptic, since it has little incommon with Roman cameos and its iconography isnot out of place in this period. 7A gold necklace found at Kuban on the north coast ofthe Black Sea in 1892 and now in Leningrad (No. 5; figs.5a—b) has three pendants as well as a clasp set with a6. Ross, DO Cat, vol. 2, no. 179 C, p. 136.7. Cf. Ross, D.O. Cat, vol. 2, p. 9, and the fifth-century Ravennaivory he cites. <strong>The</strong>re is also an unpublished Byzantine belt bucklewith the scene in a Swiss private collection.Figure 2b. Detail of figure 2a. Drawing by MarthaBreen Bredemeyer.

8 SpierFigure 3. Pendant on a chain composed of six short loop-in-loop segments.Byzantine, circa sixth century. Gold ornamented withgemstones. H (pendant): 2.6 cm (1"). New York, <strong>The</strong> Metropolitan<strong>Museum</strong> of Art, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 17.190.1660.Photo: Courtesy <strong>The</strong> Metropolitan <strong>Museum</strong> of Art, New York.gold solidus struck at Constantinople during the briefjoint reign of Justin I and Justinian in A.D. 527. <strong>The</strong>pendants are again oval shaped but are of slightly differentmanufacture from the previous examples. <strong>The</strong>yare flatter, and the front sides are set with banded-agategems surrounded by two rows of beaded wire with aplaited-wire band between them. <strong>The</strong>y do not have theborder of punched dots. All three pendants have a loopat the bottom for a small pendant, only one of whichsurvives—pear shaped with a beaded-wire rim set witha gem. Two of the pendants have patterns similar tothose seen on No. 4, while the larger central pendanthas a modified pattern so that an IX Christogram isformed, again outlined by the stylized acanthus leaves.<strong>The</strong> engraved pattern of a pendant in a Swiss privatecollection (No. 6; figs. 6a—b) is highly stylized, but theworkmanship is very fine. <strong>The</strong> engraving is bold, andthe leaves are accentuated by rows of punched dotsdown the spines. <strong>The</strong> added beaded wire is thick andcarefully molded, and the pendant itself is one of thelargest of the group. It is set with a remarkable constructionconsisting of a glass cover over an enamel that8. Ross, DO Cat, vol. 2, no. 145, pp. 100-101. See K. Wessel,Byzantine Enamels (Shannon, Ireland, 1969), no. 16, pp. 66—67, whodates the Dumbarton Oaks example circa A.D. 900.9. <strong>The</strong> enamel is both stylistically and technically very unusualand needs further examination. <strong>The</strong> goldwork appears certainlygenuine.10. P. Orsi, Sicilia bizantina (Rome, 1942), vol. 1, pp. 135-141. Thatthe pendant belongs to the group here under discussion was already

A Byzantine Pendant 9depicts a seated Virgin and Child; all of this is mountedin a gold frame. <strong>The</strong> enamel is unlike the main series ofthe Middle Byzantine period but seems stylisticallyclose to one relatively early example in DumbartonOaks showing a standing Virgin and Child, most likelydating from the late ninth or early tenth century A.D. 8In both examples the unusual colors, notably the whiteskin, and the large, round eyes are similar. A tenthcenturydate is therefore best for the enamelwork ofNo. 6, but the pendant itself clearly belongs with theothers in the sixth or seventh century. <strong>The</strong> pendant,which probably originally held a gemstone or relic,must have been reused several hundred years after itsmanufacture. 9<strong>The</strong> Lesbos treasure—now in Athens—of Byzantinegold jewelry with coins of Phocas (A.D. 602—610) andHeraclius (A.D. 610—641) included another example (No.7; figs. 7a—b). It is very small, and the work is crude.<strong>The</strong> stylized leaves are barely distinguishable, and additionalhatch marks are added in the field. <strong>The</strong>re is noborder of punched dots.Another pendant (No. 8; fig. 8) was found early inthis century in a hoard of gold jewelry and coins atPantalica, Sicily. <strong>The</strong> illicit find was quickly dispersed,but P. Orsi was able to reconstruct much of it usingphotos of the jewelry and descriptions of the coins. 10<strong>The</strong> photograph published by Orsi shows the pendantviewed through the opening where the gemstone orother object, now missing, was set. <strong>The</strong> engraving appearsto be somewhat better than that of the Lesbostreasure example (No. 7; figs. 7a—b) but is still simpleand stylized. No border of punched dots is visible, noris there an added beaded wire. In addition to a suspensionloop on top, there are two on the sides and onebelow, perhaps for suspension of smaller pendantsin the manner of the Leningrad examples (No. 5;figs. 5a—b). <strong>The</strong> coins said to have been found at Pantalicainclude solidi of Constans II (A.D. 641—668),Constantine IV (A.D. 668—685), and Tiberius III(A.D. 698—705). Most of the other jewelry from theSicilian hoard is of unusual style and not easily paralleledby other Byzantine work; a late seventh-centurydate is most likely. This additional jewelry may havebeen manufactured in a local workshop. 11Ross has plausibly suggested that a gold disc in DumbartonOaks (No. 9; fig. 9) may be a fragmentary pendant;in which case, it would be another crude example.Figure 4a. Pendant set with agate cameo of Apollo andDaphne. Supposedly found in Sicily, circasixth century. Gold. H: 2.5 cm (1"). Washington,D.C., Dumbarton Oaks ResearchLibrary and Collection 69.<strong>15</strong>. Photo: CourtesyDumbarton Oaks Research Library andCollection, Washington, DC.Figure 4b. Back of figure 4a. Photo: Courtesy DumbartonOaks Research Library and Collection,Washington, D C<strong>The</strong> acanthus leaf pattern is abandoned in this instancefor simple hatch marks that appear between the arms ofthe cross.Finally, a hoard of Byzantine jewelry found in theexcavations at Caesarea Maritima in Israel includes acomparable example in silver with a glass cover (No.10). It is very corroded, and pieces of the back are missnotedby Ross, D.O. Cat, vol. 2, p. 9.11. A fine ring set with an aquamarine intaglio depicting Nemesiswas also said to be from the find, Orsi (supra, note 10), no. 1, p. 137,fig. 60, pi. 9. It appears to be of first-century date and must have beenan antique heirloom at the time of its burial.

10 SpierFigure 5a. Chain with three pendants set with bandedagates. Found Kuban, Russia, circa sixth century.Gold. Leningrad, State Hermitage2134/1. Photo: Courtesy State Hermitage,Leningrad.ing, making it difficult to see the engraved pattern. Itappears to be a facing, nimbate bust rather than thecross and acanthus leaf design. Other details, such asthe circular shape, the border of punched dots, and theadded beaded wire, however, all correspond to themain series of pendants under consideration. This particularexample served as a reliquary.With the exception of the last (No. 10), the pendantsall share a basic decorative pattern: a central cross surroundedby engraved acanthus leaves placed betweenthe arms and sometimes additional hatched lines in thefield. <strong>The</strong> form of the cross varies, as does the quality ofthe engraving and the care given to the pattern. <strong>The</strong>cross may have arms of equal length with flaring ends(Nos. 1—3); it may have longer vertical than horizontalbranches (No. 4; two of the pendants in No. 5; and Nos.7, 8); or it may approach the form of a Maltese cross(Nos. 6, 9). In one example (No. 5) the cross is modifiedto become an IX monogram.Originally the intention was to make a simple, underratedcross subtly stand out from the complexbackground of floral decoration that outlines it. <strong>The</strong>most successful examples are in Malibu and New York(Nos. 1, 2), where the carefully engraved acanthus patternsare bolder than the cross. <strong>The</strong> crosses on the subsequentpendants are more easily visible, and theacanthus leaves hence become more stylized; they nolonger appear rounded in shape with curving veins butas simple oval or triangular areas with a central spineand straighter veins. <strong>The</strong>y fill the fields in a more haphazardmanner and may degenerate to a state where theleaves are almost indistinguishable among the lines(No. 7) or are replaced entirely by simple hatch marks(No. 9).Although the pattern of acanthus leaves outlining across does not appear elsewhere in Byzantine art, theuse of the acanthus leaf as a subsidiary decorative deviceon metalwork was very popular. It is frequently seenengraved on silver plate in the fourth century A.D. andcontinues into the sixth and seventh centuries, as Rosshas observed. 12Elaborate patterns based on acanthusleaves are also typically found engraved below the bowlsof sixth- and seventh-century, silver liturgical spoons. 13A related pattern of acanthus leaves and cross is seenon the gold box-pendant reliquary of Saint Zachariassaid to be from Constantinople and now in DumbartonOaks (figs. 10a—c). 14<strong>The</strong> back, carefully executed inFigure 5b. Detail of figure 5a.Breen Bredemeyer.Drawing by Martha12. Ross, D.O. Cat., vol. 1, no. 7, p. 9, and cf. E. Dodd, ByzantineSilver Treasures (Bern, 1973), pp. 12—13. In addition, the cross andacanthus leaf pattern of the pendants is seen as a decorative motif inthe borders of a pair of unpublished sixth- or seventh-century, silver

A Byzantine Pendant 11Figures 6a-b. Left, Pendant set with a glass-covered enamel of the Virgin and Child.Supposedly found in Asia Minor, circa sixth or seventh century. Goldwith enamel of later date. H: 4 cm (l 9 /ie"). Right, back. Switzerland,private collection.Figures 7a-b. Left, Pendant. Found in Lesbos, circa sixth century. Gold. H: 2 cm(W). Right, back. Athens, Byzantine <strong>Museum</strong> 3039. Photos: CourtesyByzantine <strong>Museum</strong>, Athens.repousse, shows a cross within a wreath surrounded byfour acanthus leaves, all within a square linear border;around this central composition is a cable border. <strong>The</strong>sides are decorated with acanthus patterns, also workedin repousse. <strong>The</strong> front is set with an engraved gem(perhaps not the original setting, as Ross notes) surroundedby vegetal and lozenge patterns in fine opusinterrasile and a beaded-wire border.<strong>The</strong> reliquary of Saint Zacharias is of exceptionalcentury goldwork. <strong>The</strong> differences are most notable inthe execution of the fine opus interrasile and repoussework. <strong>The</strong> opus interrasile is similar to the best fourthcenturyConstantinian work from the Eastern Empire(probably from Constantinople), <strong>15</strong> and it is unlike theless skillful openwork frequently seen in sixth- andseventh-century Byzantine jewelry; the careful repoussework also has little in common with the known goldworkof the sixth century. <strong>The</strong> similarities to fourthcenturywork and the differences from typical sixth-quality and stands apart technically from other sixthbookcovers now in a Swiss private collection.13. Cf. the examples in Dalton, Early Christian, p. 35.14. Ross, D.O. Cat, vol. 2, no. 31, pp. 30-31.<strong>15</strong>. Cf. most recently D. Buckton, "<strong>The</strong> Beauty of Holiness: OpusInterrasile from a Late Antique Workshop," Jewellery Studies 1(1983-1984), pp. <strong>15</strong>-19, see p. 17 for attribution to Constantinople.

12 SpierFigure 8. Pendant. Found in Pantalica, Sicily, circa sixthcentury. Gold. H: 2.6 cm (1"). Present locationunknown. Drawing by Martha Breen Bredemeyerafter P. Orsi, Sicilia bizantina (Rome,1942), vol. 1, no. 7, p. 138, pi. 9.Figure 9. Engraved disc, perhaps from a pendant. Supposedlyfound in Constantinople, circa sixthcentury. Gold. H: 2.1 cm ( 7 /s"). Washington,D.C., Dumbarton Oaks Research Library andCollection 53.12.51. Photo: Courtesy DumbartonOaks Research Library and Collection,Washington, D.C.and seventh-century Byzantine goldwork suggest aslightly earlier date for the reliquary than that proposedby Ross, perhaps in the fifth century, although no closeparallels are known.<strong>The</strong> well-known gold reliquary box found in the oldbasilica at Pola (present-day Pula, Yugoslavia) and nowin Vienna 16forms a link between the Dumbarton Oaksreliquary and the group of pendants (figs. 11a—c). Its lidappears to have been inspired by the design of theDumbarton Oaks reliquary, but this has become highlystylized. <strong>The</strong> repousse cross within a wreath is replacedby a cross with glass paste inlay surrounded by a wreathof plaited gold wire. Four pyramidal clusters of goldbeads appear in the corners instead of the four acanthusleaves. <strong>The</strong> short sides have crosses bordered with cablesas in the Dumbarton Oaks example, but here, unlikethe Saint Zacharias reliquary, the stylized acanthusleaves fill the areas between the arms of the cross in themanner of the pendants.Perhaps from the same workshop is a gold cross inDumbarton Oaks, which shares with the Vienna reliquarybox the addition of plaited gold wire, clusters ofgold beads, and central glass paste inlay on one side.In a variation of the pendants' motif, the other side ofthe cross has engraved acanthus leaves in each arm(fig. 12). 17Other similar crosses are noted by Ross,as are rings decorated with similar plaited wire, includingan example in Oxford set with a coin of Zeno(A.D. 474-491). 18<strong>The</strong> similarities in the decoration of the DumbartonOaks cross, the Vienna reliquary box, and the group ofpendants indicate that all are products of the same koinestyle. A Byzantine koine style of jewelry, attested by alarge number of finds from all parts of the ByzantineEmpire, developed by the early sixth century, flourishedin the reign of Justinian, and continued well into theseventh century. <strong>The</strong>re can be little doubt that much ofthe material was manufactured in Constantinople andthat workshops located elsewhere, whether in the eastor the west, closely followed the fashions set in thecapital. <strong>The</strong> style encompasses a large body of material(including personal jewelry, such as belt buckles, earrings,finger rings, necklaces, and pendants, as well ascrosses and reliquaries), and the sharing of decorative16. H. Buschhausen, Die spaetroemischen Metallscrinia undfruehchristlichen Reliquiare (Vienna, 1971), no. B 20, pp. 249-252, pi.57, and K. Weitzmann, ed., <strong>The</strong> Age of Spirituality (New York, 1979),no. 568, pp. 630-631.17. Ross, D.O. Cat., vol. 2, no. 10, p. <strong>15</strong>.18. Ibid., no. 10, p. <strong>15</strong>; E. T. Leeds, Antiquaries <strong>Journal</strong> 20 (1944), no.4, p. 334, pi. 51.19. Other gold objects that display similarities in manufacture anddecorative detail can also be identified. For example, a small goldcross (H: 2.83 cm [lW]) engraved with the same pattern as the largerexample at Dumbarton Oaks (fig. 12) is now in a Swiss private collection;it is unpublished. Another similar example was on the Londonmarket a few years ago and was exhibited by Jack Ogden Ltd. (In theWake of Alexander, November 17—December 1, 1982, no. 27). <strong>The</strong> useof punched-dot borders is seen, for example, on an openwork ringfrom Smyrna (British <strong>Museum</strong> M&LA AF 308; Dalton, Early Chris-

A Byzantine Pendant 13Figures Wa-c.Left, Box-pendant reliquary of Saint Zacharias. Supposedly found in Constantinople, circa fifth century. Gold setwith an engraved gem, possibly of later date. H: 3 cm (lW); W: 2.5 cm ( 1 5 /i6"). Center, back. Right, side.Washington, D.C., Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection 57.53. Photos: Courtesy Dumbarton OaksResearch Library and Collection, Washington, D. C.Figures lla-c. Left, Reliquary Box. Found in Pula, Yugoslavia, circa sixth century. Gold with glass paste inlay. H: 1.6 cm (Vs");W: 2.3 cm ( 7 /s"); D: 1.9 cm (W). Center, top. Right, side. Drawing by Martha Breen Bredemeyer. Vienna,Kunsthistorisches <strong>Museum</strong> VII 761. Photos: Courtesy Kunsthistorisches <strong>Museum</strong>, Vienna.patterns and technical details among different types ofobjects is typical. 19<strong>The</strong> circumstances of discovery of the pendants examinedhere firmly place them in the sixth and seventhcenturies and associate them with other jewelry of thekoine style. <strong>The</strong> silver example from Caesarea Maritimawas found in the excavations with a hoard of jewelrythat, although not precisely datable, is of typicallysixth- or early seventh-century style. More helpful isthe Leningrad necklace (No. 5), which has a clasp setwith a coin precisely datable to the joint reign of Justin Iand Justinian in A.D. 527. <strong>The</strong> Lesbos treasure containedHan, no. 212, p. 33) and on the ubiquitous pear-shaped and lunateopenwork earrings, which usually show two confronted peacocks (cf.the recent summary of the literature, T. Ergil, Earrings [Istanbul,1983], no. <strong>15</strong>7, p. 62, to which others could be added). <strong>The</strong> tails of thepeacocks often resemble the stylized acanthus leaves of our No. 6,with a row of punched dots down the spine from which engravedveins branch off (cf. A. Pierides, Jewellery in the Cyprus <strong>Museum</strong> [Nicosia,1971], no. 10, p. 56, pi. 38).Also apparently related to the style and technique of the goldworkunder consideration is the Olbia treasure of Gothic jewelry fromsouth Russia, now in Dumbarton Oaks (Ross, DO. Cat, vol. 2, no.166, pp. 117—118). <strong>The</strong> date is controversial, but the similarity of theengraved decoration and pattern to Byzantine goldwork, as well asother details, suggests a dependence on Byzantine prototypes. Asixth- rather than early fifth-century date may be preferable.

14 SpierFigure 12. Cross. Circa sixth century. Gold with glasspaste inlay. H: 2.7 cm (IVIÖ"). Washington,D.C., Dumbarton Oaks Research Library andCollection 50.20. Photo: Courtesy DumbartonOaks Research Library and Collection,Washington, DC.a quantity of jewelry of typical type, as well as coins ofPhocas and Heraclius datable to the mid-seventh century.<strong>The</strong> pendant in this hoard shows a further divergencefrom the original pattern and may be indicative ofthe later examples of the group. <strong>The</strong> pendant from thePantalica hoard, which contained coins spanning thesecond half of the seventh century, is also rather crudebut fits well into the main group, although the accompanyingjewelry is not typical of the seventh-centuryByzantine style. <strong>The</strong> wide distribution of the pendantsincludes Asia Minor, south Russia, Palestine, Lesbos,and Sicily, and a similar range is seen for the comparablejewelry. This again suggests a central origin forthe style, if not for the actual manufacture—surelyConstantinople itself.Merton CollegeOxford

Kopie oder Nachschöpfung.Eine Bronzekanne im J. <strong>Paul</strong> <strong>Getty</strong> <strong>Museum</strong>Michael PfrommerDie über dreißig Zentimeter hohe Kanne muß zu denqualitätvollsten erhaltenen Bronzegefaßen mit ornamentalemDekor gerechnet werden (Abb. 1—3, 5). 1Die reiche Dekoration der Kanne ist von außergewöhnlicherQualität, sowohl im Entwurf wie auchin der Ausführung. Den Gefäßkörper schmückt einzweireihiger, ägyptischer Nymphaea Nelumbo-Kelch,zwischen dessen Blattspitzen italische Stockwerkblütengeschaltet sind (Abb. 10—12). Ein plastisch gegebeneslesbisches Kymation akzentuiert den Halsansatz. DenHals selbst schmückt eine aus Silberblech geschnitteneund eingelegte Weinranke. Figürlich verziert istallein der Henkel, bei dem ein Panskopf die untere Attaschebildet (Abb. 6), während ein kleiner Silenskopfals oberer Henkelabschluß in das Gefäßinnereblickt (Abb. 7).Das Gefäß wurde möglicherweise vor der ägyptischenKüste in der Nähe von Alexandria im Meer gefunden.Muscheln und andere Ablagerungen bestätigeneine marine Herkunft, ohne daß eine exaktere Eingrenzungdes Fundortes auf diesem Wege möglich wäre. 2Wie zu zeigen sein wird, vermag die Ornamentanalysedie Zuweisung an eine ägyptische Werkstatt zu stützen.TECHNIKWie das Fehlen jeglicher Spuren von Treibarbeit imInneren bezeugt, wurde die Kanne trotz der extremdünnen Wandung gegossen. 3Dies gilt auch für den inKaltarbeit übergangenen Blattkelch. Im Gegensatz zuder vollständig mit Silber eingelegten Weinranke aufdem Hals, zeigen auf dem Gefäßkörper nur einige wenigeBlütendetails silberne Einlagen, die in Abb. 12schwarz gekennzeichnet sind. Das gleiche gilt auch fürdas lesbische Kymation. Der Henkel ist separat gegossenund angelötet bzw. mit Nieten befestigt.GEFÄSSFORMTypologisch folgt die Kanne in etwa der von J. D.Beazley als 5a bezeichneten Gruppe. 4 Bronzekannendieses Typs sind meines Wissens kaum erhalten, dochzeigt eine große Bronzekanne aus dem thrakischen Tumulusvon Mal Tepe, daß der Typus im 3. Jahrhundertgeläufig war (Abb. 4). 5Das in der Ausführung ungleich bescheidenere MalTepe-Exemplar läßt sich in einigen formalen Datailsmit der Malibu-Kanne vergleichen. Dies gilt etwa fürdie mit einem Eierstab verzierte Lippe, den mit einemProfil von der Schulter abgesetzten Hals und ebenso fürdie spulenförmige Fingerstütze auf der oberen Henkelbiegung.Die Entwicklung der Fingerstütze läßt sich immakedonischen und italischen Raum seit dem ausgehenden4. Jahrhundert beobachten, doch besitzendiese Gefäße in der Regel gedrungenere Proportionenund keine von der Schulter abgesetzte Halspartie. 6Für die Publikationserlaubnis bin ich M. True zu herzlichem Dankverpflichtet. Für Hilfe und Hinweise verschiedener Art danke ichebenfalls K. Manchester und J. Podany. Verbunden bin ich weiterhinim besonderen Maße M. Breen-Bredemeyer für die Erstellung derZeichnungen.AbkürzungenAußer den im AJAverwendet:Pfrommer, "Studien":üblichen Abkürzungen wird im folgenden"Studien zu alexandrinischer und großgriechischerToreutik frühhellenistischer Zeit,"Archäologische Forschungen 16 (Berlin, <strong>1987</strong>).1. Malibu, <strong>The</strong> J. <strong>Paul</strong> <strong>Getty</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> 85.AB.78. Höhe: 32 cm;Durchmesser: 20.3 cm.2. Nach Auskunft des ozeanographischen Instituts in Los Angeleszeigen die Ablagerungen, daß die Kanne aus dem Meer und nicht ausSüßwasser geborgen wurde.3. Für diese technische Auskunft bin ich J. Podany und seinemStab verbunden. Die Technik des Gusses derartig dünnwandigerGefäße, einschließlich eines reliefierten Dekors, hat in der ägyptischenToreutik lange Tradition: Pfrommer, "Studien," 77f, 84 KBk 1,7-<strong>15</strong>, Taf. 6-9; 11; 12; 48c, d.4. Als Beispiel klassischer Zeit vgl. man etwa eine Kanne desMannheimer Malers in Oxford, Inv. 298, Ashmolean <strong>Museum</strong>: CVAOxford I (III 1), Taf. 43, 14.5. Sofia, Archäol. Mus.: B. Filow, BIABulg 11 (1937), 56, Nr. 18,Abb. 55, 56. Als sicher römisches Beispiel mit einem lesbischenKymation am Übergang von Hals und Schulter vgl. eine Kanne inBelgrad br. 2835/III: Lj. B. Popovic, D. Mano-Zisi, M. Velickovic,B. Jelicic, Anticka Bronza u Jugoslaviji, Narodni Muzej Beograd(Belgrad, 1969), 124, Nr. 217, Abb. 217.6. Kannen aus dem "Philippgrab" von Vergina in <strong>The</strong>ssalonikiMus.: M. Pfrommer, Jdl 98 (1983), 239. M. Andronicos, Vergina. <strong>The</strong>

16 PfrommerAbb. 1. Bronzekanne. H: 32 cm (127s"); D: 20.3 cm (8"). Malibu, <strong>The</strong>J. <strong>Paul</strong> <strong>Getty</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> 85.AB.78.

Abb. 2. Bronzekanne. H: 32 cm (12 5 / 8") ;D: 20.3 cm (8"). Malibu, <strong>The</strong> J. <strong>Paul</strong> <strong>Getty</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> 85. AB.78.Kopie oder Nachschöpfung 17

18 PfrommerAbb. 3. Profilzeichnung der Bronzekanne in Abb. 1. Zeichnung von Martha Breen Bredemeyer.

Kopie oder Nachschöpfung 19In frühhellenistischer Zeit findet sich auch derEierstabdekor der Mündung 7und das lesbische Kymationan der Nahtstelle von Körper und Hals. 8Die formalenDetails der Malibu-Kanne könnten somit füreine Datierung im 3. Jahrhundert v. Chr. sprechen.DER HENKEL UND DER FIGÜRLICHE DEKORDie Henkelform mit der großen Pansattasche und derspulenförmigen Fingerstütze (Abb. 3, 5, 6) läßt sich, wiegesagt, bereits in frühhellenistischer Zeit belegen. 9Dies gilt auch für Details wie den ins Gefäßinnereschauenden Silenskopf (Abb. 7), 10oder die Voluten zubeiden Seiten des Panskopfes. 11Die Mittelrippe des Henkels gestaltete der Toreut alssilbern eingelegte Schlange, ein Detail, für das mirkeine frühe Parallele geläufig ist.Während man dem Schlangendekor schwerlich chronologischeSignifikanz zubilligen wird, liegt der Fall beiden in Form von Schwanenköpfen gebildeten oberenEnden des Henkels gänzlich anders. Schwanenkopfattaschendieser Art sind ganz allgemein typisch für kaiserzeitlicheToreutik, wie etwa ein silberner Skyphoshenkeldes frühen 1. nachchristlichen Jahrhunderts ausVize in Ostthrakien bezeugt (Abb. 8). 12Neben pompejanischenFunden 13ist vor allem auch auf Gußformenderartiger Henkel aus dem römischen Ägypten zu verweisen.14Trotz der zahlreichen frühhellenistischen Detailformenist die Kanne somit schwerlich vor der augusteischenZeit gefertigt worden.Auch der große Panskopf zeigt unübersehbar späte,eklektische Züge. Die Gesichtszüge mit den ornamentalenUberaugenbögen und der wulstigen Nase erinnernnoch durchaus an frühhellenistische Beispiele,doch wird unschwer ein Mangel an plastischer Durchbildungdeutlich, der einen beinahe maskenartigen Eindruckhervorruft, ein Eindruck, der durch die kleine,Abb. 4. Bronzekanne aus dem Mal Tepe. Sofia, Archäologisches<strong>Museum</strong>. Zeichnung von MarthaBreen Bredemeyer.gebleckte Zunge noch verstärkt wird.Eine Reminiszenz an frühhellenistische Formen fassenwir weiterhin in den steil aufgerichteten Panshörnern. <strong>15</strong>Weit entfernt von der differenzierten, teilweise naturalistischenBartbehandlung frühhellenistischer Beispiele16 ist schließlich die schematische, unplastischeWiedergabe des Bartes, der von dem Toreuten nurRoyal Tombs and the Ancient City (Athens, 1984), <strong>15</strong>2£, Abb. 1<strong>15</strong>, 116,<strong>15</strong>8, Abb. 124. Zu weiteren Beispielen dieses Kannentyps vgl. Pfrommer,op. cit., 239-240, Abb. 1, 2.7. S.o. Anm. 6.8. Als Beispiel des ausgehenden 4. Jhs. vgl. man eine Silberkannethrakischen Typus aus Varbitza in Sofia, Archäol. Mus. 51: Gold derThraker, Ausstellung Köln, München, Hildesheim (Köln, 1979), 161,Nr. 318, Abb. 318. Für das 3. Jh. vgl. man kleine Silberkännchen inNew York, Metropolitan <strong>Museum</strong> of Art 1972.118.<strong>15</strong>6; 1982.11.13: D. v.Bothmer, BMMA 42 (1984), 49, Nr. 84, Abb.; 57, Nr. 96, Abb.9. S.o. Anm. 6.10. Dieses Motiv findet sich in klassischer Zeit etwa bei Kannendes Typs 2: T. Weber, Bronzekannen (Frankfurt am Main, 1983), 91ff,Taf. 13. Vgl. weiterhin Ptolemäerkannen: D. B. Thompson, PtolemaicOinochoai and Portraits in Faience (Oxford, 1973), Taf. 49, 60,Nr. 218, 220.11. Vgl. die Kannen o. Anm. 6.12. Istanbul, Archäol. Mus.: L. Byvanck-Quarles van Ufford,Melanges Mansel I (Ankara, 1974), 335-343, Taf. 113-116.13. Aus Boscoreale, Paris, Louvre: A. Heron de Villefosse, MonPiot5 (1899), Taf. 20; 23, 3; 24, 2.14. Turin, Museo Egizio: T. Schreiber, Die Alexandrinische Toreutik(Leipzig, 1894), Taf 1, in London, Brit. Mus.: op. cit, Taf. 3b.<strong>15</strong>. Man vgl. eine Bronzekanne in Boston (Mus. of Fine Arts99.485), bei der die Hörner zweier antithetischer Bocksköpfe inanaloger Weise auf dem Henkel angeordnet sind. M. Pfrommer,Jdl 98 (1983), 240, Abb. 2 (mit Parallelen). Zu dem Kannentypuss. o. Anm. 6.16. Pan-Attasche eines Holzkohlen-Behälters (?) oder einer Lampeaus dem "Philippgrab" von Vergina in <strong>The</strong>ssaloniki: M. Pfrommer,Jdl 98 (1983), 255-256, Abb. <strong>15</strong>. M. Andronicos, Vergina. <strong>The</strong> RoyalTombs and the Ancient City (Athens, 1984), 162f, Abb. 130, 131. DerKopf wurde von mir versehentlich als Silen mit einem Blätterkranzangesprochen. Es handelt sich jedoch fraglos um einen für Pan verwendetenSilenskopftypus. Die Attasche der Kanne ist allerdings auchnicht mit dem tierischen Pansbild einer Eimerattasche in Toronto zu

20 Pfrommerdurch parallele, straffe Strähnen gegliedert wurde.Vergleiche wären hier eher in frühklassischer Zeitzu suchen. 17Demgegenüber entspricht das plastisch aber kompaktgegebene Haupthaar späthellenistischen Bildungen(Abb. 9). Die erste und die zweite Reihe der zapfenartigen,symmetrisch geordneten Locken sind strengvoneinander abgesetzt und die hintere Reihe steil aufgerichtet(Abb. 3, 6).Verwandt, wenn auch nicht identisch, ist die Haaranlagebei den Silenskopf-Attaschen späthellenistischerund frühkaiserzeitlicher Marmorkratere. Zu nennen isthier der bereits in dem gegen 100 v. Chr. gesunkenenAbb. 5. Bronzekanne. H: 32 cm (12 5 /s"); D: 20.3 cm (8").Malibu, <strong>The</strong> J. <strong>Paul</strong> <strong>Getty</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> 85.AB.78.Mahdiaschiff vertretene Typus Mahdia-Borghese, 18sowie der jüngst von H. Froning dem mittleren 1. vorchristlichenJahrhundert zugewiesene Medicikrater. 19Das Ende der Reihe bildet ein frühkaiserzeitlicher Kratermit Rankendekor im Kapitolinischen <strong>Museum</strong>(Abb. 9). 20Wir fassen hier somit einen über längere Zeitbeliebten Attaschentypus, der sich insbesondere aufgrundder Haaranlage von frühhellenistischen Bildungenabsetzt. 21Das späthellenistische Motiv der protuberanzähnlichhochfliegenden Haare ist bei unserer Bronzekanne zitiert,jedoch eklektisch mit einer Bartbildung des 5.Jahrhunderts kombiniert.Der vor die spulenförmige Fingerstütze gesetztekleine Silenskopf (Abb. 7) zeigt eine ähnlich eklektischeMischung hellenistischer und klassischer Charakteristika.Die etwas schematische Wiedergabe des Barteserinnert durchaus an den Panskopf (Abb. 6). Details,wie der Efeukranz mit den großen Korymben, folgen dagegenVorbildern des späten 4. und 3. Jahrhunderts. 22Auffällig sind jedoch die nach späthellenistischer Maniereingezogenen Konturen einiger Efeublätter. 23Der figürliche Dekor steht somit einem bereits vonAbb. 6. Henkel der Kanne in Abb. 1 mit einem Panskopfals Attasche.vergleichen (Toronto 910.205.3): J. W. Hayes, Greek, Roman, and RelatedMetalware in the Royal Ontario <strong>Museum</strong> (Toronto, 1984), 26ff., Nr.31, Abb. 31.17. Silenskopf an einem Kantharos des 5. Jhs. aus GoljamataMogila in Plovdiv, Archäol. Mus. 1634: I. Venedikov, T. Gerassimov,Thrakische Kunst (Wien, 1973), 344, Taf. 168.18. Kratertypus Mahdia-Borghese: H. Froning, Marmor-Schmuckreliefsmit griechischen Mythen im 1. Jh. v. Chr. (Mainz, 1981), 141—142,Taf. 56, 1; 57, 1 (mit Lit.). Zu einem antiquarischen Detail vgl. Pfrommer,"Studien," Anm. 73, 77. KP 117 (3. Jh.).19. Froning, op. cit. 140-<strong>15</strong>3, Taf. 57, 2.20. Rom, Kapitolinisches <strong>Museum</strong> 275: Froning, op. cit. 141f.,Anm. 921. Man vgl. etwa die Attasche eines Bronzeeimers aus Derveni.<strong>The</strong>ssaloniki Mus.: M. Pfrommer, Jdl 98 (1983), 254, Abb. 12 (mitParallelen). Pfrommer, <strong>Getty</strong>MusJ 11 (1983), 142, Abb. 16.22. S. o. Anm. 21.23. Zu Vorstufen: Pfrommer, "Studien," 114. Die Einziehung ist

Kopie oder Nachschöpfung 21Abb. 7. Obere Henkelattasche der Bronzekanne in Abb.1 mit dem Kopf eines Silens.Abb. 8. Henkel eines silbernen Skyphos aus Vize. Istanbul,Archäologisches <strong>Museum</strong>. Photo: mitfreundlicher Genehmigung, Deutsches ArchäologischesInstitut, Istanbul; W. Schiele.den Schwanenattaschen der Henkel nahegelegten frühkaiserzeitlichenAnsatz nicht im Weg.DER BLATTKELCHWie die Gefäß form läßt sich auch der große, den Gefäßkörperumhüllende Blattkelch auf Vorbilder frühhellenistischerZeit zurückführen. Die dreireihige, in flachemRelief ausgeführte Dekoration gehört zu denNymphaea Nelumbo-Kelchen mit überfallenden Traufspitzenägyptisch-frühhellenistischen Typs. 24Die Traufspitzensind nach ptolemäischer Tradition ornamentalverziert. 25Wie bei einer Reihe frühhellenistischer Dekorationenwurden zwischen die Blattspitzen Blüteneingeschaltet. 26Wie zu zeigen sein wird, erweist sich, ungeachteteiniger späterer Details, der gesamte Dekor als Aufgriffeiner Dekoration des mittleren 3. Jahrhunderts.jedoch bei weitem nicht so stark wie an anderen frühkaiserzeitlichenDenkmälern. Man vgl. etwa Efeu am Bel-Tempel von Palmyra:H. Seyrig, R. Amy, E. Will, Le temple de Bei ä Palmyre (Paris, 1975),Taf 45, oben links.24. Zum vorhellenistischen Typus, Pfrommer, "Studien," 86—91.Zu frühen Beispielen mit eingeschalteten Blüten, Pfrommer, "Studien,"87, KBk 58, 61, Taf 60. Aus frühhellenistischer Zeit sind bisheute nur mit Akanthus gemischte Kelche bekannt, Pfrommer, "Studien,"95ff, doch dürfte dies dem Zufall der Überlieferungzuzuschreiben sein. Für einen reinen Nymphaea-Kelch mit ägyptischenKronen anstelle der Blüten, vgl. Pfrommer, "Studien," 100, 116,120f, KBk 60, Taf 61. Pfrommer, <strong>Getty</strong>MusJ\2> (1985), <strong>15</strong>, Abb. 9. Zueinem reinen Nymphaea-Kelch vgl. auch ein Bronzebecken im J. <strong>Paul</strong><strong>Getty</strong> Mus. 80.AC.84:. Pfrommer, <strong>Getty</strong>Mus] 13 (1985), 9-18, Abb. 1.25. Pfrommer, "Studien," 111, 120f Pfrommer, <strong>Getty</strong>MusJ 13(1985), 14-17.26. Pfrommer, "Studien," 95-116, Taf. 52; 53a, b.Abb. 9. Henkelattasche eines Marmorkraters. Rom, Kapitolinisches<strong>Museum</strong> 275.

22 PfrommerAbb. 10. Blütenschmuck des Blattkelchs auf dem Körperder Bronzekanne in Abb. 1 (Blütengruppe A).Abb. 11. Blütenschmuck des Blattkelchs auf dem Körperder Bronzekanne in Abb. 1 (Blütengruppe B).Der Blütenschmuck der überfallenden Traufspitzender ersten und zweiten Kelchreihe schließt eine Datierungder mutmaßlichen Vorbilder vor dem mittleren 3.Jahrhundert aus. 27Die Detaildurchformung des Nymphaeablattwerksselbst ist unmittelbar mit dem Dekoreiner Bronzevase vorgeblich iranischer Provenienz zuverbinden, die nicht früher als das 1. vorchristliche Jahrhundertangesetzt werden kann. 28Zu vergleichen sindvor allem Details wie die feine Doppelkontur der Blattränderund Mittelrippen. Abweichend von klassischenund frühhellenistischen Beispielen mit NymphaeaNelumbo-Dekoration wurden die Blattadern nicht konvexherausgearbeitet, 29sondern wie bei der Bronzevaseund bei einem Becken gleichen Materials im J. <strong>Paul</strong><strong>Getty</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> eingetieft. 30 Frühhellenistische undspäthellenistisch-frühkaiserzeitliche Blattprofilierungenverhalten sich somit bei diesen Beispielen wie Positivzu Negativ.Im Gegensatz zu der normalerweise üblichen Kelchanordnungreduzierte der Toreut bei der Malibu-Kannedie Höhe der zweiten und dritten Kelchreihe, um Raumfür die großen Blütenkompositionen zu schaffen. Bemerkenswertist weiterhin der alternierende Wechsel derBlattformen in dem hintersten Kelchregister. Neben winzigenNymphaea Nelumbo-Blättchen findet sich hierminiaturisierter Akanthus, 31 sowie einfach gezahntesBlattwerk. Im Grundaufbau ist der Blattkelch jedochnicht von frühhellenistischen Beispielen zu trennen. Diesgilt auch für die Verwendung ornamental gefüllter Traufspitzenbei den Nymphaeablättern.DIE BLÜTENFORMENDie zwischen den Blattspitzen stehenden Blütenkompositionenfolgen dem italisierenden, makedonischenBlütenrepertoire. 32Sowohl der Blütengruppe A (Abb.10, 12) wie auch B (Abb. 11, 12) liegen Stockwerkblütenitalischen Typs zugrunde (Abb. 13). 33Beim Typus A wächst aus einer großen Kelchblütemit aufwendigem Basiskelch eine große Knospe, dieihrerseits aus einem großen Kelch mit zur Seite geschlagenenBlättchen entwickelt ist. Die Komposition ist inder italisch-makedonischen Ornamentik bereits im ausgehenden4. Jahrhundert angelegt, wie etwa die Blütenkompositionauf Textilien des "Philippgrabes" in Verginazeigt (Abb. 13). 34 Verwandte Kompositionen findensich auch im frühptolemäischen Repertoire. 35Auchdie aus dieser großen Blüte wachsenden kleinen Blütchenunterschiedlichen Typs kehren in nahezu identischerForm auf den zitierten Textilien wieder—wieetwa die kleinen, im Profil gegebenen Kelchblüten mit27. Als eines der frühesten Beispiele vgl. einen Becher in NewYork, Brooklyn Mus., 55.183: Pfrommer, "Studien," 119 KBk 66, KaBA 48, Taf. 61. Pfrommer, <strong>Getty</strong>MusJ 13 (1985), <strong>15</strong>, Abb. 8. Bei diesem,aus einer ägyptischen Werkstatt stammenden Gefäß, ist das Füllmotivrein abstrakt und nicht pflanzlich.28. New York, Metropolitan Mus. of Art 66.235: Pfrommer,<strong>Getty</strong>MusJ 13 (1985), 12, Abb. 5a. Pfrommer, "Studien," Anm. 518.Vgl. auch das o. Anm. 24 zitierte Becken.29. Vgl. Pfrommer, "Studien," 86—91 und die dort zitiertenBeispiele.30. S.o. Anm. 24.31. Möglicherweise bezog der Toreut seine Anregung von denMiniaturakanthusblättchen in ptolemäischen Blattkelchdekorationendes 3. Jhs.: Pfrommer, "Studien," 116.32. Zu diesem Repertoire Pfrommer, Jdl 97 (1982), 119-190, bes.140-147.33. Zur Definition: Pfrommer, Jdl 97 (1982), 126, Abb. 1.34. Pfrommer, Jdl 97 (1982), 145, Abb. 8. M. Andronicos, Vergina.<strong>The</strong> Royal Tombs and the Ancient City (Athens, 1984), 195, Abb. <strong>15</strong>6,<strong>15</strong>7. Pfrommer, <strong>Getty</strong>MusJ 13 (1985), 17, Abb. 11.

Kopie oder Nachschöpfung 23Abb. 12. Zeichnung des Blattkelchs und des lesbischen Kymations am Halsansatz der Kanne in Abb. 1. Zeichnung von MarthaBreen Bredemeyer.den silbern eingelegten Fruchtknoten. Späte Beispieledieses Typs begegnen noch im mittleren 3.Jahrhundert. 36Einige Eigentümlichkeiten unterscheiden die BlütengruppeA (Abb. 10, 12) von spätklassisch-frühhellenistischenBeispielen. Zu nennen ist etwa die Lotosblütenangenäherte Ausgestaltung der eigentlichen Kelchblüte.Diese Variante des spätklassischen Motivs begegnet alsbekrönende Blüte auch bei der Blütenkomposition B(Abb. 11, 12) und ist, wie das zitierte Bronzebecken inMalibu zeigt, in dieser Ausgestaltung wahrscheinlichdem 1. Jahrhundert v. Chr. zuzuweisen. 37Auch hierliegen jedoch die Wurzeln im frühhellenistischen Repertoire,wie ein Gipsabguß einer ptolemäischen Phialedes früheren oder mittleren 3. Jahrhunderts bestätigt. 38Bei der Komposition A ist weiterhin die überaus festeVerbindung von Kelchblüte und bekrönender Knospebemerkenswert. Die beiden Blüten stecken förmlich ineinander,wie wir es spätestens seit augusteischer Zeitan Blütenkandelabern kennen. 39 Auch dieses Detailspricht für eine Entstehung der Vase nicht vor dem ausgehenden1. Jahrhundert v. Chr.Beachtung verdient weiterhin die Ausgestaltung desoberen Blütenrandes der Kelchblüten. Auf den überfallendenBlütenrand setzte der Toreut eine Perlreihe.Abb. 13. Blütenkomposition eines Stoffes aus dem "Philippgrab"von Vergina. <strong>The</strong>ssaloniki, Archäologisches<strong>Museum</strong>.Diese Detailform ist meines Wissens im Repertoiredes späten 4. und früheren 3. Jahrhunderts nicht geläufig,sie findet sich jedoch in der zweiten Hälfte3. Jahrhunderts auf dem Giebel des Sirenensarkophagsaus Memphis, 40deseine Parallele, die angesichts desägyptischen Nymphaea Nelumbo-Kelches der Kanneund ihres mutmaßlichen Fundortes sicherlich nichtzufällig ist.Die Blütengruppe B (Abb. 11, 12) ist ähnlich aufgebautwie A, doch kommt hier das frühhellenistische35. Man vgl. etwa Blüten auf den Reliefs des Petosirisgrabes vonHermupolis: Pfrommer, Jdl 97 (1982), 180, Abb. 20b, sowie einenGipsabguß aus Mit Rahine in Hildesheim, Pelizaeus Mus. 1161: C.Reinsberg, Studien zur hellenistischen Toreutik (Hildesheim, 1980), 66f.,303, Nr. 19, Abb. 32. Pfrommer, Jdl 97 (1982), 186, Abb. 23, 34.36. An den Antenkapitellen des Naiskos von Didyma: Th.Wiegand, H. Knackfuß, Didyma. Die Baubeschreibung (Berlin, 1941), F530, Taf. 190. Zur Datierung vgl. Pfrommer, Istanbuler Mitteilungen 37(<strong>1987</strong>), im Druck.37. Pfrommer, <strong>Getty</strong>MusJ 13 (1985), 17.38. Hildesheim, Pelizaeus Mus. 1141: Reinsberg, op. cit., 55f., 299,Abb. 21. Pfrommer, "Studien," <strong>15</strong>3, Anm. 375, 990.39. Man vgl. etwa die Ära Pacis: G. Moretti, Ära Pacis Augustae(Rom, 1948), Taf. 1 (Rankenpfeiler).40. Kairo, Ägyptisches Mus. CG 33102: C. C. Edgar, Graeco-EgyptianCoffins, Masks and Portraits, Catalogue Generale des Antiquites Egyptiennes(Kairo, 1905), 2f. Taf. 2. Pfrommer, Jdl 97 (1982), 179f, Abb. 19(Blüte). Pfrommer, "Studien," 135, Anm. 884, 1079 (mit Lit.).

24 PfrommerFormengut noch unverkennbarer zum Tragen. Die beidenBlüten der Stockwerkkomposition sind noch regelrechtmit einem Stiel verbunden und stecken nichtso fest ineinander. Der dreiblättrige Basiskelch dergroßen Kelchblüte erinnert allerdings an spätesthellenistischeBildungen wie an dem Bronzebecken inMalibu, 41jedoch lassen sich für den Blütentypus mitgezacktem Kelchrand unschwer spätklassische undfrühhellenistische Analogien anführen. 42Dasselbe giltfür die Differenzierung zwischen dem dreidimensionalgegebenen unteren Blattwerk der Lotosblüte und denim Zentrum findet sowohl spätklassische wie auch frühhellenistischeParallelen. 48Dasselbe gilt für die kleinenrahmenden Blütchen mit silbernen Fruchtknoten. 49Entgegen der hängenden Orientierung der Palmettenin den Traufspitzen auf dem erwähnten Bronzebeckenin Malibu 50sind die Blütengruppen in den Blattspitzender Oinochoe nach oben orientiert. Da es sich ja umnach vorne überhängende Traufspitzen handeln soll,wäre eine hängende Anordnung der Dekoration an undfür sich konsequenter, doch finden wir seit frühhellenistischerZeit in der Regel stehende Blütenkompositionen.in Profilansicht ausgeführten oberen Blättern. 43Chronologisch von großer Bedeutung sind schließlichdie länglichen Arazeen, die sich formal an Beispieleam Laodikebau in Milet anschließen, ein Gebäude, daswahrscheinlich in das mittlere 3. Jahrhundert datiert. 44Auch diese Blütenform deutet somit auf ein frühhellenistischesVorbild der Dekoration.Im Gegensatz zu diesen frühen Formen steht der erstim ausgehenden Hellenismus aufkommende Typus derbekrönenden Lotosblüte mit überdimensionierter Zentralblüte,auf den bereits verwiesen wurde. 45DIE BLÜTEN IN DEN BLATTSPITZEN DERNYMPHAEA-BLÄTTEREine Lotosblüte wie die bekrönende Blüte derGruppe B dient auch als Füllmotiv der überhängendenTraufspitzen der ersten Kelchreihe (Abb. 12). AlsFüllblüte des Lotos ist diesmal eine Kelchblüte mitgewelltem, jedoch nicht überfallendem Rand gewählt. 46Die beiden rahmenden, aus der großen Lotosblüteentwickelten Blüten mit dreiblättrigem Basiskelchfinden engste Analogien auf einem frühhellenistischenKieselmosaik aus Pella VI. 4 7 Auf der Kanne sind beidiesen Blüten die Fruchtknoten bzw. das Blüteninneremit Silber eingelegt. Die ganze Blütengruppe wächstaus zwei winzigen, gegenständigen Voluten, die in ganzunnaturalistischer Weise aus den Rändern der großenNymphaeablätter entwickelt wurden.Im Aufbau verwandte Blütenkompositionen schmückenschließlich die überfallenden Blattspitzen der zweitengroßen Kelchreihe (Abb. 12). Die aus einem Akanthuskelchbzw. aus glattem Blattwerk wachsende KnospeBLATTKELCH UND BLÜTEN.ZUSAMMENFASSUNGSowohl im Blattkelch wie auch in den Blütenformenspiegeln sich zwei unterschiedliche Phasen der Ornamententwicklung.Der Entwurf wie auch die überwiegendeZahl der Einzelformen sind dem Repertoiredes ausgehenden 4. und der ersten Hälfte des 3.Jahrhunderts verpflichtet, wobei die entwicklungsgeschichtlichspätesten Detailformen in die Mitte des 3.Jahrhunderts datieren. Dies gilt insbesondere für die indieser Zeit im ptolemäischen Bereich aufkommenden"gefüllten" Blattspitzen.Auf der anderen Seite sprechen einige Eigentümlichkeitender Blüten wie auch die Gestaltung der Ränderder Nymphaea Nelumbo-Blätter für eine Entstehungder Vase nicht vor dem späten 1. Jahrhundert v. Chr.Angesichts dieses Befundes bieten sich zwei Deutungsmöglichkeitenan. Entweder haben wir es bei derDekoration mit einer Nachschöpfung im Stil des 3.Jahrhunderts zu tun, oder es handelt sich um eine geringfügigim Stil der frühen Kaiserzeit modifizierteKopie eines frühptolemäischen Ornaments. Dies ist ornamentgeschichtlichvon großem Interesse, da bisherunter den erhaltenen frühptolemäischen Dekorationendie auf der Kanne vertretene Entwicklungsstufe alexandrinischerBlattkelchornamentik nicht überliefert ist.DIE WEINRANKEDie Weinreben sind zeitlich weitaus schwerer einzugrenzen.Vergleichbar, wenn auch ohne die kompliziertenVerschlingungen, ist der Dekor des Kratertypus41. Pfrommer, <strong>Getty</strong>Mus] 13 (1985), 17, Abb. Id (A-C). Weiterhin17, Abb. 5b.42. Etwa ein Kieselmosaik aus Athen: Pfrommer, Jdl 97 (1982),168, Abb. 14, oder eine apulische Schale in Ruvo: op. cit., 125, Abb. 27.43. Vgl. etwa Blüten an der Goldlarnax des "Philippgrabes." <strong>The</strong>ssalonikiMus.: Pfrommer, Jdl98 (1983), 249, Abb. 7.44. M. Pfrommer, Istanbuler Mitteilungen 36 (1986), 84, Taf 27.1.45. S.o. Anm. 24.46. Als Beispiel für viele: Krater in Neapel, Privatbesitz: A. D.Trendall, A. Cambitoglou, <strong>The</strong> Red-Figured Vases of Apulia II (Oxford,1982), 923, Taf. 358 (unten Mitte, hinter dem linken Eros). Vergleichbarist hier nur die perspektivische Ansicht und nicht der Blütentypusan sich.47. D. Salzmann, "Untersuchungen zu den antiken Kieselmosaiken,"Archäologische Forschungen 10 (Berlin, 1982), 29f, Nr. 105, Taf.38, 5 (links). Pfrommer, "Studien," 128f, 131, 138.48. Als Beispiel für viele etwa ein Kieselmosaik aus Pella: Salzmann,op. cit., 105f, Nr. 98, Taf. 31, 4.

Kopie oder Nachschöpfung 25Abb. 14. Zeichnung der Weinranke auf dem Hals der Bronzekanne in Abb. 1. Zeichnung von Martha Breen Bredemeyer.Borghese-Mahdia, 51doch läßt sich der gestreckte Rankenverlaufder Zweige bereits in spätklassischer Zeitbelegen. 52Die Weinblätter der Oinochoe entsprechen nichtmehr den vierösigen Beispielen des späteren 4. und 3.Jahrhunderts, doch ist zu beachten, daß bei Weinblattwerkin der Regel ohnehin mehrere Varianten nebeneinanderstehen. 53Die komplizierte Verschlingung der Zweige an denKreuzungspunkten läßt sich bereits an einer ptolemäischenDekoration des 3. Jahrhunderts belegen (Abb.<strong>15</strong>), 54 so daß auch hier ein frühhellenistisches Vorbild,unter Umständen sogar ein ptolemäisches, angenommenwerden kann.DAS LESBISCHE KYMATIONDas lesbische Kymation läßt sich ebenfalls auf eineAnregung des früheren 3. Jahrhunderts zurückführen.Beispiele mit geschwungener Kontur und relativ hoherBlattspitze erscheinen bereits gegen 300 v. Chr. 55DerVerzicht auf eine breite Blattspitze deutet eher auf einenAnsatz im frühen als im mittleren 3. Jahrhundert. Etwasbefremdlich wirkt die in der Traufspitze der Blätter miteinem Knick weitergeführte, dreifach konturierte Blattrahmungdes Kymations. Möglicherweise zeigt sichhier die Handschrift des frühkaiserzeitlichen Toreuten.Wahrscheinlich ist dies indes bei der kurzen, keilförmigenSpaltung der Kymatienblätter, eine Eigentümlichkeit,die sich auch an anderen toreutischen KymatienAbb. <strong>15</strong>. Gipsabguß aus Memphis. Hildesheim, Pelizaeus<strong>Museum</strong> 1135.49. Man vgl. etwa das Gnosismosaik aus Pella: Salzmann, op. cit.,107f., Nr. 103, Taf. 29 (neben dem Petasos des rechten Jägers).50. Pfrommer, <strong>Getty</strong>MusJ13 (1985), <strong>15</strong>, Abb. Id: H.51. H. Froning, Marmor-Schmuckreliefs mit griechischen Mythen iml.Jh. v. Chr. (Mainz, 1981), 146, Taf. 58, 1.52. Golddekorierte Schwarzfirniskeramik. Krater aus Capua inLondon, Brit. Mus. 71.7-22.3: G. Kopeke, AM 79 (1964), 32, Nr. 42,Beil. 19, 1 (oben rechts).53. Zum vierösigen Typus vgl. man etwa den Alexandersarkophag:V. v. Graeve, "Der Alexandersarkophag und seine Werkstatt," Ist-Forsch 28 (Berlin, 1970), Taf. 5—7. Als Gegenbeispiel vgl. man zweider Begleittheken: op. cit., Taf. 3.54. Abguß, wahrscheinlich eines Schwertknaufs aus Mit Rahine inHildesheim, Pelizaeus Mus. 1135: Reinsberg, op. cit., 64f, 302, Nr. 17,Abb. 25. Pfrommer, "Studien," 94, Anm. 65, 1324 KBk 95.55. vgl. etwa Pfrommer, <strong>Getty</strong>MusJ\2> (1985), 12, Abb. 4.

26 Pfrommerdes ausgehenden Hellenismus nachweisen läßt. 56Die anstelle der Zwischenspitzen in dem Kymationverwendeten Palmetten und Blüten entsprechen demRepertoire spätklassischer und frühhellenistischer Toreutik,so daß man auch das Kymation auf ein frühhellenistischesVorbild zurückführen darf. 57ZUSAMMENFASSUNGObwohl bei der Kanne in Form und Dekor in beträchtlichemUmfang frühhellenistische Formen zitiertsind, ist sie schwerlich vor der augusteischen Zeit gearbeitetworden. Diese späte Entstehungszeit schlägt sichunter anderem in der eklektischen Bildung der Panskopf-Attaschenieder. Im ornamentalen Bereich findetsie ihren besten Ausdruck in den Schwanenatt as chendes Henkels.Insbesondere der Blattkelch läßt sich auf das frühalexandrinischeRepertoire zurückführen und auch beianderen Formen ließen sich Verbindungen zu ptolemäischenFormen ziehen, wobei die im ptolemäischenÄgypten vorauszusetzende italisierende, makedonischeOrnamenttradition immer wieder bei dem Blütenrepertoirezum Tragen kam. Die Dekoration imitiert oderkopiert eine Stilstufe ptolemäischer Ornamententwicklung,die uns bisher an Beispielen dieser Qualität nichterhalten ist.Das Original oder die Vorbilder der Dekoration wirdman im ptolemäischen Bereich zu suchen haben. Verbindetman dies mit dem mutmaßlichen Fundort imMeer vor Alexandria, so wird man auf ein alexandrinischesAtelier etwa der augusteischen Zeit schließendürfen, das gezielt auf das überkommene eigeneFormengut zurückgriff. Trotz ihrer späten Entstehungsteht die Kanne somit in der Tradition hellenistischer Gefäßkopien.58Nicht mehr zu klären ist, ob die Kannein Form und Dekor auf ein einziges Vorbild zurückgeht,oder ob der alexandrinische Toreut seine Anregung vonverschiedenen Gefäßen und Dekorationen bezog.Deutsches ArchäoligischesInstitut, Istanbul56. Pfrommer, <strong>Getty</strong> Mus] 13 (1985), 12, Abb. 1, e: A. Diese Eigentümlichkeitfindet sich auch gelegentlich auf älteren Kymatien. Situlaaus Pastrovo in Plovdiv, Archäologisches <strong>Museum</strong> 1847: I. Venedikov,T. Gerassimov, Thrakische Kunst (Wien, 1973), 339, Taf. 107.57. Zu diesem Motiv: Pfrommer, <strong>Getty</strong>MusJ 13 (1985), 11, Abb. 1,c; e.A.58. Vgl. M. Pfrommer, <strong>Getty</strong>MusJW (1983), 135-146.

<strong>The</strong> God Apollo, a Ceremonial Table with Griffins,and a Votive BasinCornelius C. VermeuleThree very different works of Greek art have come toMalibu together (figs. 1—3). <strong>The</strong> most reliable informationseems to indicate that they were found as a groupin ruins in a mound, probably in western Greek lands.<strong>The</strong> statue of Apollo has been carved from marblewhich certainly comes from Attica, and the two elegantobjects of furniture—a ceremonial table and a votivebasin—have been fashioned out of marble from theAegean Islands of Greece, not Thasos in the north butthe area of Paros or Naxos in the Cyclades.<strong>The</strong> purpose of this study is to argue that all threesculptures were fashioned about the same time, near theend of the fourth century B.C. or at the beginning of thethird, and that they were made or assembled as a cohesivegroup in antiquity. 1Furthermore, when consideredtogether, the subjects and iconographic details of thethree objects suggest connections between the Macedoniankingdoms after the death of Alexander the Greatand Megale Hellas, the Greek world in southern Italy.<strong>The</strong> powerful personality who linked these regions togetherat this time was Pyrrhus, King of Epirus(319—272 B.C.), who for a period before 283 B.C. controlledhalf of Macedonia and <strong>The</strong>ssaly. Shortly thereafter,he came to the southernmost part of Italy to helpTarentum in the struggle against the Romans.At Locri Epizephyrii, located on the ball of the footof the Italian "boot," in ancient Bruttium (Reggio Calabria),King Pyrrhus struck a silver didrachm that is, tomy mind, one small piece of evidence connecting thelekanis, or louter (basin), with the trapezophoros (tablesupport); after a few mythological and geographicalspeculations, this link can be made to extend to thestatue of Apollo. <strong>The</strong>se connections suggest that an importantperson in touch with both Macedonian and Italian-Greekaffairs, perhaps King Pyrrhus himself, dedicatedthis ensemble in a sacred area somewhere alongthe western coast of the Adriatic Sea.APOLLO<strong>The</strong> youthful god stands with his weight on the leftleg, the left hip thrown slightly outward (fig. 1). <strong>The</strong>right leg and right foot were slightly advanced. <strong>The</strong>reare remains of a griffin seated at the left foot, its rightwing curling up between the god's left hip and thecloak wrapped around his left arm. This cloak is drawnaround, and covers most of, the back; it hangs over theright shoulder with an extra fold. In his hair the godwears a fillet, flanked by braids. This fillet is tied with aknot at the back; the two ends lie over the carefullyarranged hair. At the brow, the hair is tucked under thefillet in such a way as to allow two curls to spiral downin front of the ears. 2Apollo's lowered left hand, perhaps holding an arrow,rested above the wings of the griffin, and the righthand, perhaps holding a bow, was raised and extended.Alternatively, the extended right hand may have held aAt the <strong>Getty</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> thanks are due to John Walsh, Director,Marion True, Curator, and Arthur Houghton, former AssociateCurator, for permission to publish these sculptures. Sandra KnudsenMorgan, former Editor, was, as she has been for well over a decade, aconstant source of help and inspiration. Jifi Frei was extremely helpfulwith scholarly ideas and general information at the time these sculpturesfirst came to notice. At the <strong>Museum</strong> of Fine Arts, Boston, JanFontein, Director, and colleagues in the Department of ClassicalArt—Mary Comstock, John Herrmann, Florence Wolsky, Emily Vermeule,and Michael Padgett—have been most supportive.1. <strong>The</strong>se sculptures were catalogued by the present writer as nos.8, 9, and 10 in Catalogue of a Collection of Greek, Etruscan and RomanAntiquities (Cambridge, Mass., 1984), when they were in private handsin New York and London. Thanks also are offered to the formerowners for help in studying the three sculptures, and other works ofart, over the past years.2. Accession number 85.AA.108. H (max.): 148 cm (58V4"); W(max. at the rib cage): 46 cm (Wis), (max. at plinth): 57.5 cm (22 5 /s");D (max. at the left side of the plinth between the griffin's forepaws):24.8 cm (9 3 A"). H (max. of plinth): 3 cm (IW).Greek marble with fine but evident crystals, in my opinion, probablyPentelic and surely from Attica. Remains of an iron dowel arefound in the rectangular hole below the cloak, against the right shoulder.<strong>The</strong> mark of a modern plow runs from below the right shoulderto the middle of the right thigh. <strong>The</strong> breaks are visible in the photographs.<strong>The</strong>re are no restorations. <strong>The</strong> surfaces of the flesh were wellfinished but were not highly polished. <strong>The</strong> same is true of the draperyor cloak, both front and back. Hair and diadem are less finelyfinished, save for the diadem in front which matches the flesh surfaces.<strong>The</strong>re are root marks and encrustation at various places over thegod, the griffin, and the plinth. See "Acquisitions/1985," <strong>The</strong> J. <strong>Paul</strong><strong>Getty</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> 14 (1986), no. 6, p. 181.

28 Vermeulelibation dish (phiale) and the lowered left, the bow, oreven both a bow and an arrow. 3This impressive statue is neither a work of the periodbetween late Archaic and early Transitional Greeksculpture nor a sleek eclectic creation of the Pasiteleanperiod in Naples and Rome of circa 85 B.C. and later inthe first century. 4While incorporating memories of Atticand South Italian Greek sculpture at the time of thePersian Wars, the stance and the softened forms of thebody mark this carving as a work of the late fourthcentury B.C. or a generation later, influenced by the socalledPraxitelean traditions of Greek sculpture. <strong>The</strong>techniques of carving—the finishing in the hair, flesh,diadem, and drapery and the details of animal andplinth—as well as the simplified piecing with dowels,conform to practices of around 300 B.C. This Apollobelongs among the rare examples of so-called "Archaizing"Greek art of the period before the lateHellenistic age.Research over the past century, particularly since theFirst and Second World Wars, makes it evident that"Archaistic" Greek art began in the fifth or fourth century,rather than in the period of copyism in the firstcentury B.C. Modern terminologies ("Archaizing,""Archaistic," and "Lingering Archaic") are explained byB. S. Ridgway in <strong>The</strong> Archaic Style in Greek Sculpture. 5<strong>The</strong> <strong>Getty</strong> Apollo, by Ridgway's criteria, can be classedas "Archaizing." It is "a work of sculpture which belongsclearly and unequivocally to a period later than480 and which, for all its differences in plastic treatmentof drapery and tridimensionality of poses, retains a fewformal traits of Archaic style, such as coiffure, pattern offolds, gestures or the like." 6Unlike the Apollo from theHouse of Menander at Pompeii with its cold, polishedFigure 1. Statue of the god Apollo. Greek, circa320-280 B.C. Marble. H (max.): 148 cm(58 1 //); W (max. at the rib cage): 46 cm(18V8 W ); D (max. at the left side of the plinth):24.8 cm (9W). Malibu, <strong>The</strong> J. <strong>Paul</strong> <strong>Getty</strong><strong>Museum</strong> 85.AA.108.3. A precedent for the griffin as attribute and support placed closeto one leg is found in a statue of Dionysos with his panther positionedat the bottom of the drapery that falls from his right wrist; the sculpturewas found in a house at Priene. See <strong>The</strong>odor Wiegand and H.Schräder, Priene (Berlin, 1904), pp. 368-369, fig. 463.4. <strong>The</strong> truly Roman version of such a statue is the youthful Apolloin the Archaic style in the Museo Nazionale, Naples, from theHouse of Menander at Pompeii. See J. B. Ward-Perkins, A. Claridge,and J. Herrmann, Pompeii, A.D. 19 (Boston, 1978), vol. 2, no. 83, p.148. <strong>The</strong> archetype of the Apollo studied here was copied in Julio-Claudian times in the small marble statue in the Palazzo della Bancad'ltalia, Via Nazionale, Rome, showing that the original belonged tothe first years after, or, in Sicily, the last moments of, the Persian-Carthaginian wars. See E. Paribeni, "Di un nuovo tipo di Apollo distile severo," Antike Plastik 17, Teil 6 (1978), pp. 101-105, pis. 50-52.5. See Christine Mitchell Havelock, "Archaistic Reliefs of theHellenistic Period," AJA 68 (1964), pp. 42, 44, pi. 17, fig. 1, a relief ofHermes and the nymphs belonging to the fourth century B.C., circa320. See B. S. Ridgway, <strong>The</strong> Archaic Style in Greek Sculpture (Princeton,1977), pp. 303-319, and bibliography, pp. 320-322.6. Ridgway (supra, note 5), p. 303.

<strong>The</strong> God Apollo 29Figures 2a-b. Top, Ceremonial table with griffins. Greek, circa 320—280 B.C. Marble. H (max. at top of wings): 95 cm (377i 6"); W (max. at plinth): 20 cm (77s"), (at top of wings): 22 cm (87s"); L (max.): 148 cm (587 2"). Bottom, back.Malibu, <strong>The</strong> J. <strong>Paul</strong> <strong>Getty</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> 85. AA.106.

30 VermeuleFigure 3a. Votive basin. Greek, circa 320—280 B.C. Marble. H (max.): 30.8 cm (1276"); Diam (max. including handles): 60 cm(237s"), (max. at rim): 56 cm (22"). Malibu, <strong>The</strong> J. <strong>Paul</strong> <strong>Getty</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> 85. AA.107.body and its silly griffin looking like a puppy beggingfor a biscuit, this Apollo shows its originality by incorporatingonly those "Archaizing" elements, notably thecoiffure, necessary to identify the statue as a modern(fourth century B.C.) restyling of a venerable imagewith no attempts at academic imitation.TABLE SUPPORT: TWO GRIFFINS ATTACKING AFALLEN DEER<strong>The</strong> two griffins crouch over their fallen prey, a deer,on a rough base similar to those used for Attic funeraryanimals in the fourth century B.C. (figs. 2a—b). <strong>The</strong>curling "Ionic," or traditionally East Greek, wings aresolid between, each having a large, rectangular andhorizontal slot and a vertical groove on the facing, innersurface. This arrangement was probably designed for ametal or wooden support for the table top, which restedon the curling upper surfaces of these wings. 7<strong>The</strong> high quality of the carving and the stylistic detailsof the animals, notably the eye treated as a raisedcircle or half a ball, all indicate a date of executionwithin the period of the last Athenian funerary beasts,which extended from around the time of Alexander theGreat's death to the second decade of the third centuryB.C. For the functional use of these griffins and the deeras part of a piece of furniture, however, we have to seekparallels in the best decorative carving of the periodaround 80 B.C. and later, when so many more monumentalmarble tables and their components survive. 8Evidence from Pompeii and Herculaneum confirms thatelaborate tables in marble or metal had their places inthe homes of the wealthy, but they were also definitely7. Accession number 85.AA.106. H (max. at top of wings): 95 cm(37 7 he"); W (max. at plinth): 20 cm (7 7s"), (at top of wings): 22 cm(8W); L (max.): 148 cm (58V 2").Crystalline Greek island marble. <strong>The</strong>re are numerous breaks carefullymended with small pieces attached but with no restorations.Many traces of the red, blue, and golden brown colors survive—towit, the blue for the griffins' wings, bright red for the griffins' combs,brown or fawn color for the fallen quadruped, red also for the bloodaround the mouths of the griffins and the areas where their claws havedug into the unfortunate beast. <strong>The</strong> eyes of the griffins and especiallytheir eyeballs had brown underpainting, and the fallen animal's eyeswere red. <strong>The</strong> plinth is roughly finished; the griffins' bodies are thesmoothest parts of the sculpture. See "Acquisitions/1985," <strong>The</strong> J. <strong>Paul</strong><strong>Getty</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> 14 (1986), no. 4, p. 180.8. This ensemble has also been published, without illustration, bythe writer in "Bench and Table Supports: Roman Egypt and Beyond,"Studies in Ancient Egypt, the Aegean, and the Sudan: Essays in Honor ofDows Dunham on the Occasion of His 90th Birthday, June 1, 1980, ed. W.

<strong>The</strong> God Apollo 31Figure 3b. Interior of figure 3a.part of the furnishings of temples and had their placesin elaborate tombs. This was probably even more thecase in the period around 300 B.C.Griffins were mythological creatures associated withApollo in the east, and by Classical times the motif ofthese beasts attacking a weaker quadruped symbolizedthe forces of civilization over barbarism, the power ofthe sun rising from the east, or the divine determinationof death (sometimes sudden and quixotic) to mortals. 9As a piece of furniture, the subject as treated here wasno mere decoration for a Greek garden but was a powerfulstatement to be installed in a major votive context. 10K. Simpson and W. Davis, Jr. (Boston, 1981), p. 183.9. <strong>The</strong> ensemble has its painterly parallel on the front side of theneck of the red-figured volute krater by the Aurora Painter, fromFalerii of about 325 B.C. See M. Sprenger, G. Bartolini, and M.Hirmer, Die Etrusker, Kunst und Geschichte (Munich, 1977), p. 149,pi. 228.Dietrich von Bothmer has adduced and discussed parallels for thegriffins attacking a fallen deer in Etruscan painting and sculpture ofabout 300 B.c. in the publication of an Etruscan red-figured kantharosin the Metropolitan <strong>Museum</strong> of Art (51.11.10): BMMA 10, no. 5 (1952),pp. 145—149, with illustrations of the subject on both sides of thekantharos, on the wall of the Francois Tomb, and on the end of theolder of the two Prince of Canino sarcophagi from Vulci in the <strong>Museum</strong>of Fine Arts, Boston (86.145). For the sarcophagi, see also M. B.Comstock and C. C. Vermeule, Sculpture in Stone (Boston, 1976), no.383, pp. 244-246.10. <strong>The</strong> same school of Attic or South Italian Greek sculptors whocarved the magnificent table support also modeled the two large ter-

32 VermeuleBASIN WITH SCULPTED DETAILS AND APAINTED SCENE IN THE INTERIOR<strong>The</strong> painting in the bowl's interior comprises a whirligigof three nereids, one on a hippocamp and two onketoi; <strong>The</strong>tis is shown holding the shield of Achilles(figs. 3a—b). One other nereid holds a cuirass and thethird a helmet. <strong>The</strong> bowl has ovolo, or egg-and-dart,molding around the lip; fluted handles with floral bases,which join the body as if cast in metal and riveted orsoldered on; a circular foot enriched with waterleaf design;and, finally, below the fillet of this foot, threeanimal-foot supports rising to the circular foot withIonic fluting. 11 <strong>The</strong>se animal feet are set on a thin,slightly irregular base, and there is a heavy, columnarsupport for the entire ensemble underneath. 12Much ofthe paint remains, and the colors used are: gold for theshield; purple for the nereids' garments; reds and bluesfor the marine creatures as well as the foot of the bowl,the animal feet, the support, and the plinth.<strong>The</strong> fragile nature of the painting in the interior ofthis bowl, a traditional Greek footbath, indicates thatthe object was not made for practical use but for ceremonialpurposes. Such a basin would have made a perfectdedication in a temple or shrine; it could also havebeen made as an offering to the gods and shades in atomb, although this particular painting within an objectcarved circa 300 B.C. would have conveyed a pointedmythological, dynastic, and political message. <strong>The</strong>scene of <strong>The</strong>tis with the shield of Achilles as focal pointof a whirligig of nereids and sea creatures is watery indeed,as befits a footbath, but its symbolism is deliberatelyassociated with the Epirote ancestry of the rulingMacedonians (Alexander the Great through his motherOlympias) and their cousins and renewed connectionsin Epirus. 13<strong>The</strong> most memorable of these at this timewas King Pyrrhus.CONCLUSIONBetween about 320 and 280 B.C., probably closer tothe latter date, an Apollo standing with his griffin athis side was carved in a style that blended late Archaicfeatures with the softened forms of Praxiteleanyouthfulness. To this splendidly accomplished statuewas added a table supported by an ensemble consistingof two griffins slaying a deer. <strong>The</strong> leg of this tablewas large and strong enough to support a light top ofstone, metal, or wood on its own; there has been somespeculation that there may have been a pendant trapezophoros,which would be in keeping with the constructionof such tables in the Greek world from earlyHellenistic to Julio-Claudian and Flavian (Pompeiian)times. Finally, there is a basin with a low, rounded foot,handles, and careful enrichment imitating Greek metalworkof the fourth century B.C. <strong>The</strong> interior of thebasin was painted with a marine mythological whirligig,featuring <strong>The</strong>tis riding on a sea beast and carryingthe shield of Achilles.<strong>The</strong> table support and the basin were also probablycarved during the years when Alexander the Great'ssuccessors were consolidating their power, 320 to 280B.C. <strong>The</strong> griffins killing the deer were carried out as amasterful elaboration in painted marble of motifs andcompositions familiar in South Italy from the gildedterracotta reliefs of Tarentum. 14<strong>The</strong> basin representedthe best imitation in marble of metalwork from thePeloponnesus or Tarentum, embellished with a painteddesign popular in the koine of the fourth and third centuriesB.C. from Olynthos in Macedonia to Tarentumand beyond to Etruria.To my mind, the chain that links these three works ofart together is the silver didrachm struck by Pyrrhus ofEpirus, Macedonia, and <strong>The</strong>ssaly at Locri sometime before280 B.C. (figs. 4a—b). <strong>15</strong><strong>The</strong> reverse of <strong>The</strong>tis on asea beast with the shield of Achilles symbolizes the descentof both Alexander the Great and Pyrrhus fromthat hero; it is also the main device painted in the interiorof the <strong>Getty</strong>'s marble basin. Griffins appear on thesides of the helmet of Achilles on the coin's obverse,and these fantastic creatures who conquer in the east, asdid Alexander and Achilles, are identified with Apollo,racotta heads of stags or deer in Würzburg. See E. Simon et al., Führerdurch die Antikenabteilung des Martin von Wagner <strong>Museum</strong>s der UniversitätWürzburg (Mainz, 1975), p. 226, pi. 56. <strong>The</strong>re are Roman decorativecarvings of comparable quality, but they are rare, e.g., the head of apanther from a table support. See Jacques Chamay in J. Dörig et al.,Art antique: Collections privees de Suisse Romande (Geneva, 1975),no. 375.11. <strong>The</strong> famous nereid on a sea beast (ketos) depicted in relief onthe lid of a pyxis (jar) in gold and silver from Canosa di Puglia that isnow in the Museo Nazionale, Taranto, is a contemporary parallel. SeeE. Langlotz and M. Hirmer, Ancient Greek Sculpture of South Italy andSicily (New York, 1965), pp. 69-70, pi. XX. For other, varied views ofthe subject, see H. Sichtermann, "Nereo e nereide," in EnciclopediadelVarte antica, classica e Orientale (Rome, 1963), vol. 5, pp. 421—423, and S.Reinach, Repertoire de peintures grecques et romaines (Paris, 1922), p. 40.12. Accession number 85.AA.107. H (max.): 30.8 cm (12V8"); Diam(max. including handles): 60 cm (23 5 /s"), (max. at rim): 56 cm (22").Crystalline Greek island marble. A curved section is missing at thebowl's rim, and there are chips around the molding of the rim. <strong>The</strong>handles have been broken, repaired, and rejoined. See "Acquisitions/1985,"<strong>The</strong> J. <strong>Paul</strong> <strong>Getty</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> 14 (1986), no. 5, p. 180.13. Gold medallions from Aboukir with the bust of Olympias onthe obverse and <strong>The</strong>tis in a nereid and triton composition on thereverse are work of the late Severan period (A.D. 230) in the traditionof early Hellenistic Macedonia. See <strong>The</strong> Search for Alexander: An Exhibition(Boston, 1980), nos. 10, 11, pp. 103-104. A full bibliography on