Pittsburgh Legal Journal Opinions - Allegheny County Bar Association

Pittsburgh Legal Journal Opinions - Allegheny County Bar Association

Pittsburgh Legal Journal Opinions - Allegheny County Bar Association

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

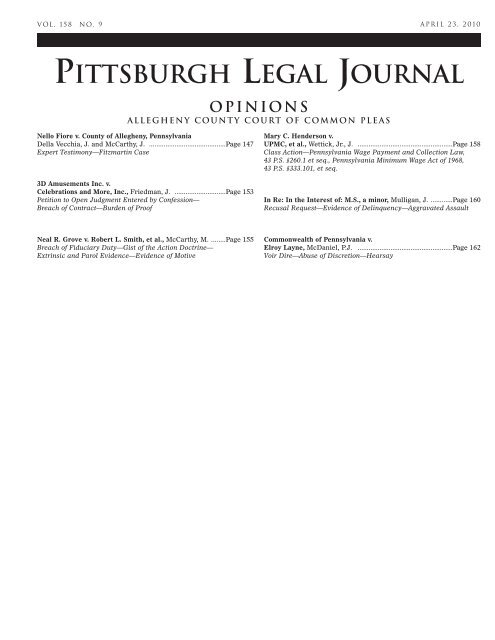

VOL. 158 NO. 9 April 23, 2010<br />

PITTSBURGH LEGAL JOURNAL<br />

OPINIONS<br />

allegheny county court of common pleas<br />

Nello Fiore v. <strong>County</strong> of <strong>Allegheny</strong>, Pennsylvania<br />

Della Vecchia, J. and McCarthy, J. ..........................................Page 147<br />

Expert Testimony—Fitzmartin Case<br />

3D Amusements Inc. v.<br />

Celebrations and More, Inc., Friedman, J. ............................Page 153<br />

Petition to Open Judgment Entered by Confession—<br />

Breach of Contract—Burden of Proof<br />

Neal R. Grove v. Robert L. Smith, et al., McCarthy, M. ........Page 155<br />

Breach of Fiduciary Duty—Gist of the Action Doctrine—<br />

Extrinsic and Parol Evidence—Evidence of Motive<br />

Mary C. Henderson v.<br />

UPMC, et al., Wettick, Jr., J. ....................................................Page 158<br />

Class Action—Pennsylvania Wage Payment and Collection Law,<br />

43 P.S. §260.1 et seq., Pennsylvania Minimum Wage Act of 1968,<br />

43 P.S. §333.101, et seq.<br />

In Re: In the Interest of: M.S., a minor, Mulligan, J. ............Page 160<br />

Recusal Request—Evidence of Delinquency—Aggravated Assault<br />

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v.<br />

Elroy Layne, McDaniel, P.J. ....................................................Page 162<br />

Voir Dire—Abuse of Discretion—Hearsay

PLJ<br />

The <strong>Pittsburgh</strong> <strong>Legal</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> is a supplement to the<br />

Lawyers <strong>Journal</strong>, which is published fortnightly by the<br />

<strong>Allegheny</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Bar</strong> <strong>Association</strong><br />

400 Koppers Building<br />

<strong>Pittsburgh</strong>, Pennsylvania 15219<br />

(412)261-6255<br />

www.acba.org<br />

©<strong>Allegheny</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Bar</strong> <strong>Association</strong> 2010<br />

Circulation 6,331<br />

PLJ EDITORIAL STAFF<br />

Frederick N. Egler, Jr. ............Editor-in-Chief and Chairman<br />

Jennifer A. Pulice ............................................................Editor<br />

Joanna Taylor ..................................................Assistant Editor<br />

David A. Blaner ..........................................Supervising Editor<br />

Lynn E. MacBeth ..............................................Opinion Editor<br />

Sharon Antill ................................................Typesetter/Layout<br />

Opinion Editorial VOLUNTEERS<br />

Mary Ann C. Acton<br />

Kenneth M. Argentieri<br />

William <strong>Bar</strong>ker<br />

Shannon F. <strong>Bar</strong>kley<br />

Colleen L. Becker<br />

Joseph H. Bucci<br />

Meg L. Burkardt<br />

Norma M. Caquatto<br />

Margaret M. Cassidy<br />

Elizabeth Chiappetta<br />

Elizabeth F. Collura<br />

Robert A. Crisanti<br />

William R. Friedman<br />

Margaret P. Joy<br />

Sandra Lewis Kitman<br />

Patricia Lindauer<br />

Mary Long<br />

Ingrid M. Lundberg<br />

family law opinions committee<br />

Reid B. Roberts, Chair<br />

Mark Alberts<br />

Christine Gale<br />

Mark Greenblatt<br />

Margaret P. Joy<br />

Patricia G. Miller<br />

Sally R. Miller<br />

Mary Kay McDonald<br />

Daniel McIntyre<br />

Laura A. Meaden<br />

Linda A. Michler<br />

Ronald D. Morelli<br />

Rhoda Shear Neft<br />

Jana S. Pail<br />

Peter C.N. Papadakos<br />

Diane <strong>Bar</strong>r Quinlin<br />

Jeffrey Alan Ramaley<br />

Danielle D. Rawls<br />

Angel L. Revelant<br />

Carol L. Rosen<br />

Amy R. Schrempf<br />

Joan O’Connor Shoemaker<br />

Carol Sikov-Gross<br />

Amy L. Vanderveen<br />

JoAnn F. Zidanic<br />

Sophia P. Paul<br />

David S. Pollock<br />

Sharon M. Profeta<br />

Hilary A. Spatz<br />

Mike Steger<br />

William L. Steiner<br />

OPINION SELECTION POLICY<br />

<strong>Opinions</strong> selected for publication are based upon<br />

precedential value, clarification of the law, procedure in<br />

<strong>Allegheny</strong> <strong>County</strong> courtrooms and elucidation of points of<br />

law. <strong>Opinions</strong> are selected by the Opinion Editor and/or committees<br />

in a specific practice section. An opinion may also be<br />

published upon the specific request of a judge.<br />

<strong>Opinions</strong> deemed appropriate for publication are not<br />

disqualified because of the identity, profession or community<br />

status of the litigant. The guide to publication is the helpfulness<br />

of the opinion to practitioners in the particular area<br />

of law. All opinions submitted to the PLJ are reviewed for<br />

publication and will only be disqualified or altered by Order<br />

of Court.<br />

OPINIONS<br />

The <strong>Pittsburgh</strong> <strong>Legal</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> provides the ACBA members<br />

with timely, precedent-setting, full text opinions, from<br />

various divisions of the Court of Common Pleas. Each opinion,<br />

which is published in this section, begins with a brief<br />

description or a “head-note” of the opinion that follows.<br />

These opinions can be viewed in a searchable format on the<br />

ACBA website, www.acba.org.<br />

CAPSULE SUMMARIES<br />

The <strong>Pittsburgh</strong> <strong>Legal</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> provides the ACBA members<br />

with precedent-setting, “Capsule Summaries” or a brief<br />

description of opinions from the Family Division of the Court<br />

of Common Pleas of <strong>Allegheny</strong> <strong>County</strong>.<br />

BINDERS<br />

The <strong>Allegheny</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Bar</strong> <strong>Association</strong> is taking orders<br />

for 3-ring binders for easy storage of PLJ opinions. Call<br />

Peggy for details, (412) 261-6255.

april 23, 2010 page 147<br />

Nello Fiore v.<br />

<strong>County</strong> of <strong>Allegheny</strong>, Pennsylvania<br />

Expert Testimony—Fitzmartin Case<br />

1. Plaintiff claims an ownership interest in all of the coal contained within those portions of the “<strong>Pittsburgh</strong> Seam” of coal located<br />

in South Park Township, <strong>Allegheny</strong> <strong>County</strong>, Pennsylvania. The surface of the subject property lies in an area designated as<br />

“South Park,” component of the <strong>Allegheny</strong> <strong>County</strong> Park System.<br />

2. Plaintiff sought to enter said property for the purpose of core drilling to determine the location of the coal, the amount of coal<br />

contained and the most feasible means of mining that coal.<br />

3. Crux of litigation is whether Plaintiff must obtain permission from <strong>Allegheny</strong> <strong>County</strong> to strip mine portions of the “<strong>Pittsburgh</strong><br />

Seam” that he believes he owns.<br />

4. <strong>Allegheny</strong> <strong>County</strong> denied Plaintiff access to enter the property to begin the process of mining the coal.<br />

5. It was not error for the trial court to admit opinion testimony on the ultimate issue in the case from an attorney who testified<br />

that the lack of specific language in the grant to allow strip mining was intended to limit the grantee to deep mining only.<br />

6. The trial court did not err in holding that the language of the grants at issue were not general enough or broad enough to<br />

include strip/surface mining as set forth in Commonwealth v. Fitzmartin, 102 A.2d 893 (Pa. 1954). In Fitzmartin, the Court<br />

advanced a four (4) factor to determine whether strip mining may be an appropriate method of extraction of subsurface minerals<br />

when the deed is silent as to the acceptable method of mining.<br />

7. Court did not find the surface of property in South Park Township to be “unimproved terrain,” the fourth factor in the<br />

Fitzmartin case.<br />

(JoAnn F. Zidanic)<br />

Thomas W. King, III for Plaintiff.<br />

Michael H. Wojcik for Defendant.<br />

No. GD 08-021519. In the Court of Common Pleas of <strong>Allegheny</strong> <strong>County</strong>, Pennsylvania, Civil Division.<br />

OPINION<br />

Della Vecchia, J. and McCarthy, J., December 22, 2009—This matter comes before the Commonwealth Court on the appeal of<br />

Nello Fiore, Plaintiff (Plaintiff or Fiore) from the Memorandum and Order of this Court dated August 17, 2009.<br />

1. BACKGROUND<br />

Nello Fiore, Plaintiff in the above matters, filed two separate actions at the above numbers, the first being a declaratory judgment<br />

action at GD 08-21518 and the second being a Petition for the Appointment of a Board of Viewers, i.e. a de facto taking at GD<br />

08-21549 regarding coal rights under a certain parcel of land in a public park known as South Park, which is owned and operated<br />

by <strong>Allegheny</strong> <strong>County</strong>. 1 The purpose of both actions is to obtain the right for or recognize the right of the Plaintiff to “strip mine”<br />

certain coal contained in a section of the Park without the permission of the surface owner, i.e. <strong>Allegheny</strong> <strong>County</strong>.<br />

This matter was assigned to Judge Michael A. Della Vecchia, and by his request, Judge Michael E. McCarthy joined him in the<br />

resolution of these matters. 2 The parties specifically requested of the Court at a status conference on December 22, 2008, that the<br />

Court first resolve the issue of whether or not Plaintiff has the right to employ a strip mining method to extract coal from the subject<br />

property. The Court agreed to the parties’ request; and accordingly did not and has not ruled upon the pending Preliminary<br />

Objections.<br />

The coal underlying the subject property was severed from the surface by Deeds from James W. Stewart to Albert C. Rohland<br />

(Deed Book Vol. 1161, Pg. 487 (dated February 15, 1902); Albert C. Rohland to the Pennsylvania Mining Company (dated March 6,<br />

1902). The severance was not by reservation but by grant. The deed to Pennsylvania Mining Company is recorded in the <strong>Allegheny</strong><br />

<strong>County</strong> Clerk of Records Office at Deed Book 1180 Page 148.<br />

Thereafter, the March 6, 1902 Deed was corrected by Deed dated April 30, 1909 from Albert C. Rohland and Elizabeth G.<br />

Rohland to <strong>Pittsburgh</strong> Coal Company (formerly Pennsylvania Mining Company), now known as Consolidation Coal Company. This<br />

severance was also by direct grant and not by reservation. Said Deed is recorded in the <strong>Allegheny</strong> <strong>County</strong> Clerk of Records Office<br />

at Deed Book 1638 Page 65.<br />

Plaintiff inherited his interest in the mineral rights from his brother, Fred Fiore. The late Fred Fiore had acquired said coal<br />

rights in a deed dated March 4, 1985 from Consolidation Coal Company. Said deed is recorded in the <strong>Allegheny</strong> <strong>County</strong> Clerk of<br />

Records Office at Deed Book 7233 Page 318.<br />

Plaintiff claims an ownership interest in all of the coal contained within those portions of the “<strong>Pittsburgh</strong> Seam” of coal located<br />

in South Park Township, <strong>Allegheny</strong> <strong>County</strong>, Pennsylvania. The surface of the subject property lies in an area designated as<br />

“South Park,” a component of the <strong>Allegheny</strong> <strong>County</strong> Park System. The crux of this litigation is whether that circumstance requires<br />

Fiore to obtain permission from <strong>Allegheny</strong> <strong>County</strong> to strip mine portions of the “<strong>Pittsburgh</strong> Seam” that he believes he owns.<br />

Plaintiff sought to enter said property for the purpose of core drilling to determine the location of the coal, the amount of coal<br />

contained and the most feasible means of mining that coal. Plaintiff insists that he has the right to extract the subject coal by strip<br />

and/or surface mining methods. Plaintiff further asserts that there are 716,700 tons of coal contained in said tract.<br />

The dispute arose when, on or about June 17, 2008, Plaintiff communicated his intention and was denied access by <strong>Allegheny</strong><br />

<strong>County</strong> to enter the property to begin the process of mining the coal. The denial was communicated by letter dated July 2, 2008,<br />

from the office of <strong>Allegheny</strong> <strong>County</strong> Chief Executive, the Honorable Dan Onorato. 3<br />

The Complaint as filed alleges that the value of metallurgical grade coal, the type that Plaintiff believes is under the subject<br />

property, is valued at One Hundred Forty-Three Dollars ($143) per ton. Based on these figures, Plaintiff contends that the coal<br />

rights at issue are valued at One Hundred Two Million Four Hundred Eighty Eight Thousand Dollars. ($102,488,000), (See,<br />

Complaint, Exhibit D).<br />

Despite Plaintiff’s estimate of the value of the coal, said rights were purchased for Five Thousand Dollars ($5,000) by Plaintiff’s<br />

brother, Fred Fiore, in 1985. Additionally, in September 1997, in the inventory filed in his capacity as Executor for the Estate of

page 148 volume 158 no. 9<br />

Fred Fiore, Deceased, Plaintiff reported value of the coal rights at One Hundred Dollars ($100). See, <strong>Allegheny</strong> <strong>County</strong> Will Book<br />

Volume 567, Page 1096.<br />

II. PROCEDURAL HISTORY<br />

This cause of action was initiated by a Complaint in Civil Action – Declaratory Judgment, filed on October 9, 2008 at General<br />

Docket (hereinafter “GD”) number 2008-02158. Also, a Petition for Appointment of Viewers, asserting a de facto taking was filed<br />

at GD 2008-021549 based on the same facts and allegations. <strong>Allegheny</strong> <strong>County</strong> filed Preliminary Objections in both actions.<br />

A status conference was held on December 22, 2008. The parties, through their respective counsel, requested that the Court<br />

answer the threshold question of whether or not the coal grant in Plaintiff’s chain of title authorized surface mining of the coal<br />

without the permission of the surface owner. On March 3, 2009, an Order was issued scheduling an argument regarding Plaintiff’s<br />

coal interest for April 15, 2009. 4<br />

Following said argument, this Court determined that, in light of Plaintiff’s great reliance on the Fitzmartin case, that a factual<br />

hearing should be held to determine whether or not the four factors used to establish the extent of a grantee’s mining rights under<br />

Fitzmartin were met in the present case. The Court did so without ruling as to the precedential impact of Fitzmartin in this matter.<br />

On April 24, 2009, this Court issued an Order stating,<br />

[H]aving heard argument on April 15, 2009, regarding the issue of “whether or not the grant of coal rights in Plaintiff’s<br />

chain of title confer upon Plaintiff the right to strip mine on the subject real estate” and the Court, after hearing argument<br />

and reviewing Briefs and Supplemental Briefs, has decided that a hearing is required to determine the following:<br />

1. Whether or not Plaintiff’s case has met the criteria for surface mining set forth in the four factors of the Fitzmartin<br />

case.<br />

2. The exact record of prior litigation involving the Plaintiff of his predecessors-in-title claim to coal and mining rights<br />

within South Park in 1978 and 1979 and any other years that litigation occurred.<br />

3. What governmental entity(ies)(local, county, state or federal) has/have the authority to grant Plaintiff the right to<br />

mine the subject property, surface or deep, and what steps need to be taken by Plaintiff to obtain legal approval to<br />

mine the subject property.<br />

(Order dated April 24, 2009)<br />

The hearing was scheduled for July 20 and 21, 2009. The parties were instructed to file Pre-Hearing Statements with the Court<br />

ten (10) days prior to the hearing. In anticipation of said hearing, the Court (both judges), with all parties present, viewed the property<br />

on July 13, 2009.<br />

Following the view and a two-day hearing, the Court authored a Memorandum and Order of Court, which was filed on August<br />

18, 2009. The Court held that Plaintiff does not meet all of the qualifications in the Fitzmartin case, if in fact that case is still controlling<br />

(discussed infra). The Court held that the mere fact that the subject deeds do not specifically ban strip mining does not<br />

mean that this type of mining is permitted.<br />

The Plaintiff took exception to this ruling and on September 14, 2009, and filed a Notice of Appeal to the Commonwealth Court.<br />

Based on this Notice and pursuant to Pa.R.C.P. 1925(b), this Court directed the Plaintiff to file a Concise Statement of Matters<br />

Complained of on Appeal. (Order dated September 28, 2009). Said Statement was timely filed on September 30, 2009, placing this<br />

matter before the Commonwealth Court of Pennsylvania. 5<br />

III. ISSUES RAISED ON APPEAL<br />

Plaintiff raises the following claims of error:<br />

1. The Trial Court committed an error of law on holding that the Plaintiff does not possess the right to strip/surface mine<br />

the property subject to this action.<br />

2. The trial court’s finding that Plaintiff does not have the right to strip/surface mine the subject parcel is not supported<br />

by the record.<br />

3. The trial court erred in finding that the property subject to this case is “improved” within the meaning of<br />

Commonwealth v. Fitzmartin, 102 A.2d 893 (Pa. 1954).<br />

4. There is not sufficient factual evidence of record to support the finding that the property subject to this action is<br />

“improved” within the meaning of Commonwealth v. Fitzmartin, 102 A.2d 893 (Pa. 1954).<br />

5. The trial court committed an error of law in finding that the property subject to the present action is “improved” within<br />

the meaning of Commonwealth v. Fitzmartin, 102 A.2d 893 (Pa. 1954).<br />

6. The trial court erred in holding that the language of the grants at issue are not general enough or broad enough to<br />

include strip/surface mining as set forth in Commonwealth v. Fitzmartin, 102 A.2d 893 (Pa. 1954).<br />

7. The trial court erred in holding that the character of the property not subject to this action, i.e. adjoining property, is<br />

relevant to the matters at issue.<br />

8. The <strong>County</strong> Parks Director’s testimony, and the record as a whole, was insufficient to support a finding that the<br />

Property subject to this case is “improved” within the meaning of Commonwealth v. Fitzmartin, 102 A.2d 893 (Pa. 1954).<br />

9. The trial court’s finding that deep mining was the exclusive method of coal extraction is not supported by the record<br />

and an error of law.<br />

10. The trial court erred in finding that a “mountain bike trial” is an “improvement” within the meaning of<br />

Commonwealth v. Fitzmartin, 102 A.2d 893 (Pa. 1954).<br />

11. The trial court failed to consider the previous litigation involving the coal rights subject to this case in that the<br />

Defendant herein was a party to litigation in 1978 and 1979. The Defendant <strong>County</strong> sought to have the subject coal mined

april 23, 2010 page 149<br />

by the surface mining method in 1979 by another mine operator. As settlement of the subsequent claim for Interference<br />

with Contractual relations, the subject coal was transferred to the Plaintiff’s predecessor in interest. Said events establish<br />

Defendant’s consent/concession that the subject coal would be mined by the surface/strip mining method.<br />

12. The trial court failed to consider and recognize the Defendant’s prior settlement and consent in the chain of [title] of<br />

the coal subject to this action. That is, the trial court failed to hold, contrary to the evidence of record, that the <strong>County</strong><br />

consented in litigation filed in 1978 and 1979 that the subject coal would be surface/strip mined by the Plaintiff’s predecessor<br />

in interest, Fred Fiore.<br />

13. The trial court erred in admitting opinion testimony from an attorney relative to the ultimate issue for the Court. The<br />

question before the Court was the interpretation of the language contained in deeds and the attorney invaded the province<br />

of the Court.<br />

14. The trial court erred in applying standards for deed interpretation when it found that the subject description did not<br />

permit extraction of the coal by the strip/surface mining method when it held that “deep mining was the exclusive method<br />

of coal extraction.”<br />

15. Such other matters as may be specified after receipt and review of the transcript of July 20-21, 2009 hearings. 6<br />

III. DISCUSSION<br />

For the purpose of setting forth a coherent discussion of the issues raised by Plaintiff Fiore, the Court has made the following<br />

groupings:<br />

A. Interpreting the coal clauses in the subject deeds (see matters complained of numbers 1, 2, 6, 9, 13 and 14).<br />

B. In determining whether or not the Fitzmartin case standards were met by Plaintiff Fiore (see matters complained of numbers<br />

3, 4, 5, 7, 8 and 10).<br />

C. In determining the effect of prior litigation (see matters complained of 11 and 12).<br />

D. General Discussion<br />

This Court makes the following response to Plaintiff Fiore’s allegations of error:<br />

A. Regarding Interpreting the Coal in The Subject Deeds And Related Matters:<br />

Plaintiff reduces the pertinent language of the underlying instruments to the following:<br />

The 1902 Grant:<br />

All the coal…in and under all that certain tract of land…. Together with all and singular property improvements ways,<br />

waters, water-courses, rights, liberties, privileges, hereditaments and appurtenances whatever thereunto belonging or in<br />

anywise appertaining and the reservations and remainders rents, issues and profits hereof; and all the estate, right, to the<br />

interest property, claim and demand whatsoever, of the said party of the first part, in law, equity or otherwise howsoever<br />

of in and to the same and every part thereof.<br />

The 1909 Grant:<br />

Together with the right to mine and remove all and any part of the coal, without being required to provide for the support<br />

of the overlying strata or surface, and without being liable for any injury to the same, or to anything thereon or therein<br />

by reason therefore by reason of the manufacture of the same, or other coal into coke, and with all reasonable privileges<br />

for ventilating, punching and draining the mine together with the free and uninterrupted right of way through and<br />

under said lands, and to build, keep and maintain, roads and ways, in and through said mines forever, for the transportation<br />

of said coal, and if coal and other things necessary for mining purposes, from and to other lands which now or hereafter<br />

may belong to said party of the second part, its successors and assign. This deed being made for the purpose of vesting<br />

mining rights in the said <strong>Pittsburgh</strong> Coal Company of Pennsylvania, formerly Pennsylvania Mining Company.<br />

Together with all and singular treatments, hereditaments and appurtenances thereunto belonging or in anywise appertaining<br />

and the reversions, remainders, rents, issues and profits thereof; and also all the estate, right, title, interest, property,<br />

claim and demand whatsoever, as well in as in equity of the said parties of the first part, of, in or to the described<br />

premises, and every part and parcel thereof, with the appurtenances. To Have and To Hold, all and singular the above<br />

mentioned and described premises together with the appurtenances unto the said party of the second part, its successor<br />

and assigns forever.<br />

Fiore maintains that the aforementioned grants are as general as could be fashioned. Fiore interprets this language liberally, by<br />

placing emphasis on the language “free and uninterrupted right of way through and under said lands,” which is exactly what Fiore<br />

had planned to do, i.e. “move through the land (surface) to extract the coal.<br />

Fiore further maintains that he would not be responsible for any damage to the property, noting that the 1909 grant explicitly<br />

provides that the grantee may “mine and remove all and any part of the coal, without being required to provide for the support of<br />

the overlying strata or surface, and without being liable for any injury to the same, or to anything thereon or therein” Plaintiff<br />

interprets the aforesaid language as a license to strip or surface mine the subject property.<br />

Strip mining, as the term indicates, is the stripping away of the earth surface and the horizontal withdrawal of the mineral<br />

deposits at hand. Shaft mining involves the sinking of a vertical shaft into the ground and the developing from that<br />

point of tunnels and galleries which serve as vantage points from which to withdraw and [lift] the coal deposits through<br />

the shaft. Shaft mining does a minimum of damage to the outer crust of the earth; strip mining does a maximum of damage.<br />

Strip mining is affected through steam shovels and bulldozers which turn up the top layer of the earth.<br />

(Commonwealth v. Fitzmartin, 102 A.2d 893, 894-5 (Pa. 1954), citing Rochez Bros., Inc. v. Duricka, 97 A.2d 825, 826 (Pa.<br />

1953)).<br />

Plaintiff does acknowledge that he has a responsibility to reclaim the property after the proposed surface mining is complete<br />

pursuant to the laws and regulations of the Commonwealth. The Plaintiff will further acquiesce to “all rules and regulations of the<br />

Department of Environmental Protection which will govern the environmental impact of said mining operations” if he was to be

page 150 volume 158 no. 9<br />

permitted to mine the subject property.<br />

In summary, Plaintiff insists that the grant in the present case is sufficiently broad to include strip mining, as evidenced by the<br />

absence of a prohibition against strip mining in the language of the grant. Further, Plaintiff claims a right to mine all of the coal.<br />

Additionally, Plaintiff maintains he has a release of obligation to provide surface support and a waiver of liability for any surface<br />

damage that might occur. Plaintiff submits, that, in any event, inasmuch as the surface is unimproved, any surface damage would<br />

be negligible. (Brief of Fiore Regarding Coal Rights at p. 20).<br />

Plaintiff takes exception to this Court’s decision to allow the <strong>County</strong> to call Samuel L. Douglas as an expert in the field of writing<br />

and interpreting mineral rights. Mr. Douglas is an attorney with over fifty (50) years experience in a practice that specializes<br />

in mineral-coal, oil and gas rights. (Tr. at 175-76). Mr. Douglas has participated in the creation or examination of “thousands of coal<br />

severance deeds.” (See Tr. at 178)<br />

Mr. Douglas served as the coordinator and president of the Energy Mineral Foundation, a foundation engaged in the edification<br />

of lawyers by way of sharing case law concerning the subject matter at issue in the present case. (Tr. at 178-9). Plaintiff did not<br />

object on the record to Samuel L. Douglas being qualified as an expert by this Court, but, on the contrary, recognized Mr. Douglas<br />

as “an outstanding attorney in this county.” (Tr. at 179). Moreover, to the extent that Mr. Douglas proffered background on conveyances<br />

that grant surface mining rights and practices historically observed within this region, such testimony was certainly not<br />

similar to the sort introduced in Commonwealth v. Neal, 421 Pa.Super. 478, 618 A.2d 438 (1992), as to the effectiveness of counsel.<br />

Plaintiff’s reliance upon Neal is misplaced.<br />

Furthermore, it was made explicit to the parties that Mr. Douglas was being allowed to render an opinion that this Court was<br />

free to accept or reject. (Tr. at 180). It was the opinion of Mr. Douglas that it would have been, “highly unusual for any case to say<br />

without the word ‘strip mining’ to allow strip mining. And I certainly don’t think strip mining was anticipated in this case, or surface<br />

mining, whatever you want to call it by today’s nomenclature.” (Tr. at 187).<br />

Mr. Douglas went on to explain that particular language used in the conveyance, “under,” “across,” “ventilation,” ‘waiver of surface<br />

support’ as well as language that was absent, such as “upon” or “waiver of lateral support.” Said language, or lack thereof,<br />

leads Douglas to conclude that the grant was intended to limit the grantee to deep mining only. (Tr. at 188-9). This opinion was rendered<br />

over the objection of Plaintiff. (Tr. at 189).<br />

Pennsylvania law allows expert testimony as to the ultimate issue. See Commonwealth v. Daniels Co., 390 A.2d 172 (Pa. 1978);<br />

Cooper v. Metropolitan Life Insurance Co., 186 A.2d 125 (Pa. 1936). “The trial judge has discretion to admit or exclude expert opinions<br />

on the ultimate issue depending on the helpfulness of the testimony versus its potential to cause confusion or prejudice.”<br />

McManamon v. Washco, 906 A.2d 1259, 1278-79 (Pa.Super. 2006). Therefore, “the trial court will not be reversed in ruling upon the<br />

admissibility of testimony to the ultimate issue in the case unless the trial court clearly abused its discretion and actual prejudice<br />

occurred.” Childers v. Powerline Equipment Rentals, Inc., 681 A.2d 201, 210 (Pa.Super. 1996). Additionally, Pa.R.E. 704, entitled<br />

“Opinion on Ultimate Issue,” provides that “testimony in the form of an opinion or inference otherwise admissible is not objectionable<br />

because it embraces an ultimate issue to be decided by the trier of fact.”<br />

Plaintiff had the opportunity to introduce expert testimony on any pertinent matter. Plaintiff’s counsel conceded Douglas was<br />

an expert, but saw no value in introducing expert testimony to rebut Douglas’ testimony (Tr. at 179-181). Plaintiff did, however,<br />

introduce testimony from two experts (Kenneth Koten (Tr. 110 et seq.) and Jonathan Hiser (Tr. 82 et seq.). Both testified that<br />

the best way to mine the coal on the subject property was by strip mining. This testimony did not significantly aid the Court in<br />

resolving the underlying issue of whether or not Plaintiff possessed the right to strip the subject property without the <strong>County</strong>’s<br />

permission.<br />

More problematic for Plaintiff was testimony regarding the “red stone seam” that sits on top of the coal owned by Plaintiff (Tr.<br />

at 257-59; see also Exhibit 28). Mr. Simonetti testified that the red stone seam overlies the <strong>Pittsburgh</strong> seam, i.e. the Plaintiff’s seam.<br />

The witness testified that, in order for Plaintiff to surface mine the property, he would need to also obtain permission to surface<br />

mine the red stone seam in which Plaintiff has no ownership interest. (Tr. at 260).<br />

B. Regarding the Fitzmartin case:<br />

Plaintiff maintains there are no permanent improvements or buildings on the subject property, no railroad lines, no public highways<br />

or any improvements of any kind that would be affected by the proposed surface mining. Plaintiff relies heavily on the<br />

Fitzmartin case. The “narrow question” involved in Fitzmartin was: did the reservation of mineral rights in the several deeds of<br />

conveyance of that particular tract of land give the defendants, the lessees of the mineral rights, the right to remove coal and other<br />

minerals from the land of the plaintiff by the open pit or strip mining method, or were they restricted to shaft or deep mining? See<br />

Fitzmartin, 102 A.2d 893, 894.<br />

As in the instant case, the deed in Fitzmartin, did not clearly set forth the rights of the parties. “Where a deed or agreement or<br />

reservation therein is obscure or ambiguous, the intention of the parties is to be ascertained in each instance not only from the language<br />

of the entire written instrument there in question, but also from a consideration of the subject matter and of the surrounding<br />

circumstances.” (Id., string cite omitted).<br />

The courts of this Commonwealth have routinely attempted to give effect to the reasonable intent of the parties at the time of<br />

conveyance when determining the rights to mine coal under a particular grant. Heidt v. Aughenbaugh Coal Company, 176 A.2d 400,<br />

401 (Pa. 1962). It is the interpretation of the words of the document which determines whether the method of removing the coal<br />

may be by strip mining or another method. See, Mt. Carmel Coal Co. v. M.A. Hanna Co., 89 A.2d 508, 510 (Pa. 1952)).<br />

Fitzmartin advanced a four (4) factor test to determine whether strip mining may be an appropriate method of extraction of<br />

subsurface minerals when the deed is silent as to the acceptable method of mining: (1) the general language in the grant is broad<br />

enough to include strip mining, (2) there is no prohibition against strip mining, nor limitation to strip mining, (3) the owner clearly<br />

has the right to mine all the coal, together with a release of the right of support and all damages to the surface, and (4) the nature<br />

of the land is unimproved terrain.<br />

Plaintiff contends that the four (4) factors considered by the Supreme Court in Fitzmartin are met in this case. Plaintiff summarizes<br />

that case to stand for the general proposition that ownership of a general grant of coal together with an absence of any<br />

obligation of surface support, without language to the contrary, accords a right to strip mine. Based upon that proposition,<br />

Plaintiff asserts that there is no question as to his “right to enter onto the subject property, explore the subject tract for the location<br />

and quantity of the said coal, and conduct surface mining operations on said tract, all without the consent of the Defendant<br />

surface owner.”

april 23, 2010 page 151<br />

Plaintiff maintains, consistent with the fourth factor of Fitzmartin, that the subject land is unimproved, differentiating the<br />

land from that described in Rochez Bros, Inc. v. Duricka. 7 In Rochez Bros., the Supreme Court denied the mineral estate<br />

owner the right to strip mine the property based in part upon the fact that the property was agricultural and contained rich<br />

soil, ideally fit for farming. Plaintiff maintains that the subject property is more akin to the property in Commonwealth v.<br />

Fisher, 8 where the tract in question was unimproved mountain land and the Supreme Court ruled that the property could be<br />

strip mined.<br />

Perhaps Plaintiff’s most accurate assertion is that, “the case law interpreting documents regarding coal grants and the right to<br />

engage in surface/strip mining is fact specific…and that the “Pennsylvania appellate courts have issued decisions that are seemingly<br />

in conflict, but, upon close reading, are determined based upon the facts of the particular case.” (Brief of Plaintiff below<br />

Regarding Coal Rights at p. 20). This case is no different. Based on the facts of this case, as applied to the body of law in this area,<br />

the Court found that the Plaintiff failed to prove compliance with factor one (1) and four (4).<br />

At the time of the original conveyances, strip mining was not employed in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania or in the<br />

<strong>Allegheny</strong> <strong>County</strong> area. Further, when there is no expressed intent in the deed concerning the means by which coal is to be mined,<br />

neither strip mining nor deep mining being specifically mentioned, the deed merely referring to ‘mining’ in general, the intent of<br />

the parties must therefore be implied. Stewart v. Chernicky, 266 A.2d 259, 263 (Pa. 1970)<br />

In this case, the language of the grant states, “without being required to provide for the support over the overlying strata or surface<br />

and without being liable for any injury to same,” this language has been held to refer specifically to deep mining operations.<br />

See, Rochez Bros., 97 A.2d 825, 826. This Court cannot find that the grantor contemplated its property being decimated by bulldozers<br />

and steam shovels, resulting in a “maximum of damage” and forever changing the landscape of the property by a grant method<br />

that was not then prevalent in this area.<br />

As to the fourth factor; the Court did not find the surface of said property to be “unimproved terrain.” The <strong>County</strong>’s Director of<br />

Parks, Andrew Baechle, credibly testified as to a 2002 study in which the property in question was selected as a “biological zone<br />

to be operated as open space reserve.” (Tr. at 119-121). Mr. Baechle went on to testify that if Plaintiff were to be permitted to strip<br />

mine the property, the property would not be restored to its current state for one hundred (100) years. (Tr. at 126). Furthermore,<br />

the <strong>County</strong> master plan recommends that this area be preserved as a biological zone, which is the home of thirty (30) species of<br />

plants and twenty-seven (27) species of birds. (Tr. at 122-26).<br />

Although such information was very powerful and thought provoking, perhaps more compelling in the context of this litigation<br />

was the fact that there are walking trails which are designated on maps provided by the <strong>County</strong>. In addition bike trails transverse<br />

the subject tract of land. (Tr. at 126). Mr. Baechle testified that he actually has ridden his bicycle on the trails (Tr. at 154).<br />

The <strong>County</strong>’s argument in this respect is bolstered by a grant of Two Hundred Fifty Thousand Dollars ($250,000) the <strong>County</strong><br />

received to improve and expand the trails and the <strong>County</strong>’s intention to further utilize the property. (Tr. at 127). Additionally, the<br />

subject property is surrounded by an amphitheater, a game reserve that houses South Park’s famous buffalo, a skateboard park,<br />

tennis courts, a wave pool and a BMX track that is regarded as the number one track of this kind in the nation over the past three<br />

(3) years. (Tr. at 127-28).<br />

The instant case is easily distinguishable from Fitzmartin. The Fitzmartin Court found significant the fact that the surface of<br />

said property was uninhabited, unimproved, mountainous terrain. This Court finds the property more akin to Rochez Bros. than<br />

Fitzmartin and adopts the <strong>County</strong>’s description of the subject property, in that, “South Park is part of the <strong>County</strong>’s Regional Park<br />

System utilized by residents of the <strong>County</strong> for a vast array of recreational purposes. It is neither uninhabited nor unimproved and<br />

is a rustic oasis in a heavily urbanized county.”<br />

C. Regarding the Effect of the Prior Litigation:<br />

Plaintiff takes exception with this Court’s failure to consider or recognize the prior litigation, settlement and consent in the<br />

chain of title of the coal subject to this action taking place in the late 1970s. Plaintiff is mistaken; this Court considered this prior<br />

litigation but found it unfavorable to Plaintiff. This Court found significant that Consol, which granted rights to Fred Fiore in the<br />

1985 deed, stated through that company’s then vice president, Thomas G. Norris, stated that any entity planning to surface-mine<br />

the subject coal tract must obtain surface mining rights from the county. (Tr. at 219).<br />

This Court finds it difficult to accept that Consol, a company actively engaged in the mining business would find it necessary to<br />

obtain <strong>Allegheny</strong> <strong>County</strong>’s consent to surface mine when no such consent was required. This Court finds further difficulty in<br />

accepting the fact that Consol would sell said rights for Five Thousand Dollars ($5,000) when the alleged true value is over One<br />

Hundred Million Dollars ($100,000,000, present values accounted for).<br />

D. General Discussion<br />

Generally speaking, although this Court’s ultimate decision is not predicated on this point, this Court finds that Plaintiff’s plan<br />

for strip mining the subject property is further flawed by an inability to obtain the proper permits necessary to begin his mining<br />

operation. Both testimonial and documentary evidence was introduced asserting that Plaintiff would not be able to obtain the mandated<br />

government permits to commence a surface mining operation on the subject property. In this connection, Defendant called<br />

Thomas G. Simonetti, a senior engineer employed by the Boyd Company whose position since 1989 was to examine permitting<br />

issues as they relate to surface mining. Mr. Simonetti credibly testified as to his familiarity with Pennsylvania’s Surface Mining<br />

Conservation and Reclamation Act, as well as the federal counterpart, the Federal Surface Mine Control and Reclamation Act. (Tr.<br />

at 230-39).<br />

Mr. Simonetti testified that “the [proposed] surface mining activities are a very disruptive process. And it would certainly<br />

change the characteristics of this Sleepy Hollow area and its current use in a public park.” (Tr. at 242). The witness was asked to<br />

turn his attention to 25 Pa. Code Section 86.102, relating to where mining is prohibited or limited. 9 The regulations involve the prohibitions<br />

and limitations of mining where publicly owned parks would be adversely affected. (Tr. at 243). Said limitations would<br />

require permission not only from <strong>Allegheny</strong> <strong>County</strong>, the owner having jurisdiction over the park, but also from the regulatory<br />

authority, the Department of Environmental Protection (hereinafter “DEP”). Further, in advance of filing an application for a surface<br />

mining permit, Plaintiff would need to file a Notice of Intent to Explore with the DEP. (Tr., at 244; See also, Exhibits 11B, 16).<br />

At the time of this litigation, none of the requisite notices or applications had been submitted. It must also be noted that the municipality<br />

in which the subject coal is located, South Park Township, has an Ordinance prohibiting mining.<br />

Additionally, and apart from all of the above, Pennsylvania law is rich with cases that seem to militate against Plaintiff Fiore’s<br />

position:

page 152 volume 158 no. 9<br />

A party engaged in strip mining must either own (or lease from one who owns) both the estate of coal and the surface<br />

estate Or own (or lease from one who owns) a coal estate which includes the right to employ the strip mining method, for<br />

such a process entails the actual stripping away of the outer covering of the terrain.<br />

Owens v. Thompson, 385 Pa. 506, 123 A.2d 408 (1956)<br />

And this Court does not wish to interfere with its use or hinder its economic viability. Yet we cannot help but realize<br />

that ‘in view of the surface violence, destruction and disfiguration which inevitably attend strip or open mining, * * *<br />

no land owner would lightly or casually grant strip mining rights, nor would any purchaser of land treat lightly any<br />

reservation of mining rights which would permit the grantor or his assignee to come upon his land and turn it into a<br />

battleground with strip mining’…. Therefore, ‘the burden rests upon him who seeks to assert the right to destroy or<br />

injure the surface’…to show some positive indication that the parties to the deed agreed to authorize practices which<br />

may result in these consequences. Particularly is this so where such operations were not common at the time the deed<br />

was executed.<br />

What the parties manifestly intended was that the coal was to be removed by the method, then known, and accepted as<br />

usual and commonplace. This was vertical tunnel, or shaft mining. Needless to say, the nature and consequence of strip<br />

mining are vastly different. If what the defendant asserts was intended, the deed should have clearly said so. If any such<br />

rights were intended and reserved, then every public and private building in the anthracite coal region could be demolished,<br />

the surface ravaged, and the entire area leveled in ruin and desolation. Surely, no court of law should construe a<br />

writing to effectuate such consequences, unless the terms thereof are unmistakable and beyond doubt.<br />

Wilkes-<strong>Bar</strong>re Twp. School Dist. v. Corgan, 170 A.2d 97, 99-100, (Pa. 1961; internal citations omitted)<br />

The specific question presented is whether the reservations quoted above allow the plaintiff company to remove coal<br />

through strip mining methods or whether it is restricted to shaft mining. Strip mining, as the term indicates, is the<br />

stripping away of the earth surface and the horizontal withdrawal of the mineral deposits at hand. Shaft mining<br />

involves the sinking of a vertical shaft into the ground and the developing from that point of tunnels and galleries which<br />

serve as vantage points from which to withdraw and lift the coal deposits through the shaft. Shaft mining does a minimum<br />

of damage to the outer crust of the earth; strip mining does a maximum of damage. Strip mining is effected<br />

through steam shovels and bulldozers which turn up the top layer of the earth as easily as a can opener lays bare the<br />

contents of a box of sardines.<br />

It is obvious, in view of the surface violence, destruction and disfiguration which inevitably attend strip or open mining,<br />

that no landowner would lightly or casually grant strip mining rights, nor would any purchaser of land treat lightly any<br />

reservation of mining rights which would permit the grantor or his assignee to come upon his land and turn it into a battleground<br />

with strip mining.<br />

There is nothing in the two quoted reservations which would cause the defendants to assume that they had contracted to<br />

allow steam shovels and bulldozers to invade their farm. In the 2.25 acres tract, all that is conveyed is the ‘* * * right to<br />

enter in, upon and under the lands * * * for the purpose of * * * mining.’ This phraseology contains no right to remove the<br />

overlying surface. If the grant was intended to include strip mining privileges, the immunity from responsibility for ‘damages<br />

to the surface * * * or the failure to provide support for the overlying strata’ would be meaningless because strip<br />

mining encompasses the very tearing away of the overlying strata.<br />

Rochez Bros., Inc., supra, at 826<br />

IV. Conclusion<br />

This Court granted Plaintiff an evidentiary hearing, argument and a view of the subject property. Nothing more could have been<br />

done to accommodate Plaintiff. After all of same, it seems abundantly clear to this Court that the Plaintiff does not possess the right<br />

to strip mine those portions of the <strong>Pittsburgh</strong> Seam that he owns underlying the Defendant’s public park. For the reasons aforementioned,<br />

this Court respectfully requests the Commonwealth Court of Pennsylvania to affirm this Court’s Memorandum and<br />

Order dated August 17, 2009.<br />

BY THE COURT:<br />

/s/McCarthy, J. and Della Vecchia, J.<br />

Dated this 22nd day of December 2009<br />

1 The Plaintiff had filed another action at GD 08-21519, which he subsequently discontinued. The <strong>County</strong> has filed Preliminary<br />

Objections to both pending actions.<br />

2 Judge Della Vecchia is the former Recorder of Deeds of <strong>Allegheny</strong> <strong>County</strong> and Judge McCarthy is the former Chairman of the<br />

Board of Viewers of <strong>Allegheny</strong> <strong>County</strong>.<br />

3 The Court questioned whether or not the letter from the <strong>County</strong>’s Chief Executive in fact denied Fiore permission to enter or<br />

required Fiore to perform certain acts precedent to entering on the subject property. (Tr. at 82).<br />

4 This Court did not agree to rule on the Preliminary Objections generally, but merely to opine as to Plaintiff’s right to strip mine<br />

under the subject deeds.<br />

5 Whether or not this matter is properly before the Commonwealth Court is for that Court to decide.<br />

6 As of this writing, the Court has not been provided with any additional matters complained of.<br />

7 97 A.2d 825 (Pa. 1953)<br />

8 72 A.2d 568 (Pa. 1950)<br />

9 The approximate federal counterpart may be found at 30 CFR Section 761.11

april 23, 2010 page 153<br />

3D Amusements Inc. v. Celebrations and More, Inc.<br />

Petition to Open Judgment Entered by Confession—Breach of Contract—Burden of Proof<br />

1. A clerical error resulting in an incorrect amount due in a confessed judgment can simply be corrected where the amount due<br />

is undisputed.<br />

2. The defendant failed to adduce sufficient evidence that the plaintiff had breached the contract sufficient to create a question<br />

of fact for a jury in order to justify the opening of the confessed judgment. Specifically, the defendant did not demonstrate that his<br />

late notice of termination of a contract to the plaintiff was reasonable under the circumstances nor did he show that the plaintiff<br />

did not suffer prejudice from the late notice.<br />

(Mary Long)<br />

Michael F. Fives for Plaintiff.<br />

M. Lawrence Shields III for Defendant.<br />

No. GD 08-19235. In the Court of Common Pleas of <strong>Allegheny</strong> <strong>County</strong>, Pennsylvania, Civil Division.<br />

MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF ORDER<br />

Friedman, J., December 30, 2009—Plaintiff confessed judgment against Defendant for the breach of a contract between them<br />

that allegedly was renewed for one year because Defendant did not properly terminate it.<br />

Defendant filed a Petition asking this Court to either strike the judgment or open it. The basis for striking the judgment is the<br />

discrepancy between the amount stated as being due in the Complaint and the amount of the judgment actually entered. Defendant<br />

contends that this is fatal. The amount is $13,447.89 in the Complaint; the amount of the judgment confessed is $15,350.37. The discrepancy<br />

came from a clerical or mathematical error which Plaintiff asks that we correct. Defendant asks in the alternative that<br />

the judgment be opened if not stricken and that the error be corrected by that route. We conclude that an incorrect amount which<br />

comes from obvious overreaching would require the judgment be stricken, but an incorrect amount that comes, as is undisputed<br />

here, from a clerical mistake and which is undisputed requires only that the mistake be corrected.<br />

This Memorandum will deal primarily with whether or not the judgment should be opened for other reasons. In order to support<br />

its Petition to Open, Defendant took the depositions of Lawrence Daurora, an owner and officer of Plaintiff, and Chris Scaff,<br />

an owner and officer of Defendant. Both depositions were taken the same day, Mr. Daurora’s first and then Mr. Scaff’s.<br />

The evidence submitted by Defendant, taken in the light most favorable to Defendant, shows the following scenario. Defendant,<br />

through Arthur Scaff, the father of Chris Scaff, entered into a contract with Plaintiff dated October 10, 2003. A few years later,<br />

Arthur contracted meningitis and became disabled. He has not been declared incompetent, but his ability to understand and<br />

remember numbers is said to have been impaired. He was not deposed. In June 2008, Chris Scaff began reviewing the calculation<br />

of the commissions Plaintiff was paying Defendant from the cash collections Plaintiff made every two weeks. He did not understand<br />

why a particular amount was deducted from the bi-weekly gross. He believed the contract did not call for that and felt that<br />

Plaintiff was cheating Defendant. He raised this with Mr. Daurora on July 2, 2008 and told him Defendant was going to stop using<br />

Plaintiff’s machines and would buy its own. Mr. Daurora said Defendant had made this threat not to renew before, prior to entering<br />

into the instant five-year contract dated October 10, 2003, so he told Chris Staff to be sure to follow the contract if that ended<br />

up being what Defendant wanted to do. (The contract provided, in 4B, that it would renew for an additional year automatically<br />

unless Defendant sent, by registered mail, its written notice of intent not to renew at least 90 days before October 10, 2008, i.e. by<br />

July 10, 2008.)<br />

Defendant sent Plaintiff a letter on July 16, 2008, stating it was “no longer going to deal with” Plaintiff. The implication is that<br />

it also did not wish to renew. The reason given was that it regarded Plaintiff as “dishonest.” Mr. Daurora’s testimony was he does<br />

not have that letter in his file and does not recall seeing it before the date of his deposition. Despite the gist of Mr. Daurora’s testimony<br />

being that he did not have such a letter, Defendant adduced no evidence of the letter being mailed. There is no contention<br />

that it was sent before July 10th nor that it was sent by registered mail. In early August, Defendant sent Plaintiff another letter,<br />

this one by certified mail, telling it to remove the various equipment that Plaintiff owned and Defendant leased per the contract.<br />

Defendant says, in effect, that this pre-expiration action is not a breach of the contract but rather was a response to prior<br />

breaches by Plaintiff. Defendant also argues that it has adduced sufficient evidence of actual notice before the 90-day period of its<br />

intent not to renew and that Plaintiff was not entitled to “renew” the contract for another year.<br />

In its brief, Defendant contends that it has three meritorious defenses to Plaintiff’s claim, paraphrased below:<br />

1. That Plaintiff is the breaching party by not paying $5,000, so that Defendant was justified in canceling the contract and<br />

demanding that Plaintiff remove its equipment.<br />

2. That Plaintiff is the breaching party by failing to pay Defendant the correct amount of commissions during the term of<br />

the contract, again thereby justifying Defendant’s cancellation of the contract.<br />

3. That Defendant had lawfully terminated the contract prior to asking Plaintiff to remove his equipment.<br />

It is undisputed that the $5,000 payment to Defendant had been promised, however, Defendant has not produced sufficient evidence<br />

of this alleged non-payment to raise a jury question. 1<br />

Defendant’s deposition of Mr. Daurora elicited evidence that Plaintiff had paid Defendant in full via the father, Arthur Scaff,<br />

who had run Defendant until either 2005 or 2006 when he contracted meningitis. Defendant has adduced no evidence other than<br />

the unsupported suspicion of Chris Scaff that the $5,000 was not paid to Defendant. Defendant has the burden of adducing sufficient<br />

evidence to require submission to a jury. Here, a jury would have to speculate.<br />

Similarly, Defendant has adduced no evidence that supports Chris Scaff’s suspicion of the miscalculation of commissions.<br />

Daurora Deposition Exhibit 1 is the relevant contract. Paragraph 3B clearly sets forth that “Touchtunes digital downloading jukebox<br />

systems have an $80.00 per week guarantee for company [Plaintiff] and commissions paid to Proprietor [Defendant] will be<br />

40% after the minimum guarantee is met.”<br />

Chris Scaff contends that the contract, taken literally, does not permit an initial deduction before Defendant’s commission is calculated.<br />

This is incorrect, since 3B does call for that, as mentioned above. However, the evidence Defendant adduced from Mr.<br />

Daurora suggests that the written contract was modified orally by himself and Arthur Scaff, whenever circumstances changed during<br />

the term of the instant contract. No evidence was adduced from Arthur Scaff regarding Mr. Daurora’s version of the oral

page 154 volume 158 no. 9<br />

changes. In any case, Defendant has failed to raise a jury question regarding the correct method of calculation. At best, it has<br />

offered the unsupported conjecture of Chris Scaff, with whom Plaintiff never dealt until July 2, 2008, according to the evidence<br />

presented.<br />

Since those two alleged breaches are what Defendant says justified the cancellation, that third “defense” must also fail.<br />

Defendant says there are at least five questions to be submitted to a jury; although our conclusions regarding the insufficiency<br />

of evidence makes these questions moot, we will nevertheless discuss them, albeit somewhat repetitively. The questions Defendant<br />

says are raised are quoted below from its brief:<br />

1. Did the Defendant validly terminate the Agreement on July 2, 2008?<br />

2. Did the Defendant validly terminate the Agreement on July 16, 2008?<br />

3. What, if any, actual damage did Plaintiff suffer as a result of written notice not being given by Defendant to Plaintiff<br />

on or before July 11, 2008?<br />

4. Did the Plaintiff change its position to its detriment as a result of said notice not being given by Defendant to Plaintiff<br />

on or before July 11, 2008?<br />

5. Is it unconscionable to give effect to the automatic renewal provision of the Agreement on the basis that termination<br />

notice was untimely under the facts and circumstances of this case?<br />

Defendant has adduced no evidence to support a jury finding in its favor to any of the questions; in particular, it has not produced<br />

more than one person’s speculation regarding the alleged breaches by Plaintiff. It has produced no evidence to suggest that<br />

Plaintiff suffered no harm as the result of the late written notice of termination. The burden at this stage is not on Plaintiff to do<br />

anything. It is Defendant that must come forward with evidence, if only to rebut the presumption that there must have been a business<br />

reason for the 90-day notice. We cannot presume the 90-day notice provision is unconscionable per se, and Defendant has not<br />

produced any evidence of circumstances here that would make enforcement of the notice provision unconscionable.<br />

Defendant cites to Music Inc. v. Henry B. Klein Co., 213 Pa.Super. 182, 245 A.2d 650 (1968) for the proposition that strict enforcement<br />

of a notice period is not required where time was not made of the essence in the contract. Defendant’s reliance is misplaced.<br />

Music Inc. involved an appeal of a judgment entered after a trial, not a petition to open a judgment entered by confession. The burdens<br />

of adducing evidence in those two situations are vastly different. Here it is solely Defendant who must adduce sufficient evidence<br />

to raise a jury question. The standard set forth in Music, Inc., regarding notice provisions such as that at issue here, is a twopronged<br />

one, that “a finding [is permitted] that a termination notice is sufficient even though delivered later than the period<br />

specified in the contract when the terminating party acted reasonably under the circumstances and there is no demonstrable prejudice<br />

resulting from the delayed notice.”<br />

Here, Defendant has adduced no evidence to suggest it acted reasonably under the circumstances nor has it adduced evidence<br />

that Plaintiff did not suffer any prejudice. At most, Defendant produced contradictory testimony from one of its owners, Chris<br />

Scaff, who says at one point in his deposition that he never saw the contract until after Plaintiff sent him a copy after the cancellation,<br />

and, at another point, that he read the contract and could not see where it allowed the deduction before commissions, and<br />

that he therefore concluded that Plaintiff was cheating. Regardless of when he himself actually read the contract, the testimony of<br />

Chris Scaff does not show that he was reasonable in sending the written notice on the 16th of July (by ordinary mail) or the 11th<br />

of August (by certified mail). Notice was due July 10th. The first prong of the Music Inc. test, reasonableness of the Defendant, is<br />

clearly not met.<br />

Similarly, there is no evidence at all regarding the second prong, lack of prejudice to Plaintiff. Lawrence Daurora for Plaintiff<br />

admits that Chris Scaff told him on July 2, 2008 that he was not satisfied with Plaintiff’s calculation of the commissions Defendant<br />

was entitled to and that Defendant was not going to use Plaintiff’s services in the future. However, Mr. Daurora also indicated<br />

that Defendant had made similar threats in the past. Mr. Daurora further testified that he told Chris Scaff to be sure to cancel<br />

properly under the contract. Chris Scaff’s response in his own testimony was that he didn’t know that notice of non-renewal had<br />

to be in writing. His deposition was taken immediately after Mr. Daurora’s and, in that context, his failure to deny Mr. Daurora’s<br />

version of that aspect of the conversation is an implicit admission that he was reminded to check the contract if he wanted to cancel<br />

properly.<br />

Defendant says it is entitled to have a jury evaluate Plaintiff’s credibility. However, it is Defendant, not Plaintiff, who, in order<br />

to open a judgment, has to adduce evidence to contradict Plaintiff’s statement. That statement is part of Defendant’s evidence here.<br />

Defendant had the burden to produce evidence that untimely notice was nevertheless sufficient notice in the circumstances. The<br />

circumstances shown by the evidence Defendant adduced include the unrebutted and uncontradicted “fact” that Defendant had<br />

made a similar threat at the earlier renewal period and had then carried it out by sending notice as required by the contract, after<br />

which Defendant renewed anyway. Defendant does not contest this so we have no jury question here either.<br />

We therefore must deny both the Petition to Strike and the Petition to Open. However, we grant the Plaintiff’s request to correct<br />

the amount of the judgment. See Order filed herewith.<br />

BY THE COURT:<br />

/s/Friedman, J.<br />

Dated: December 30, 2009<br />

ORDER OF COURT<br />

AND NOW, to-wit, this 30th day of December 2009, it is hereby ORDERED that Defendant’s Petition to Strike and Petition to<br />

Open are DENIED for the reasons set forth in the accompanying Memorandum in Support of Order. Plaintiff’s request to correct<br />

the amount of the judgment to $13,447.89 is hereby GRANTED, and the Department of Court Records, Civil Division is directed<br />

to mark the docket accordingly.<br />

BY THE COURT:<br />

/s/Friedman, J.<br />

1 The $5,000 seems to have been an incentive from Plaintiff to Defendant to renew on an earlier occasion after Defendant had properly<br />

notified Plaintiff of its intent not to renew. Its actual purpose is immaterial as both sides agree it was promised.

april 23, 2010 page 155<br />

Neal R. Grove v.<br />

Robert L. Smith, et al.<br />

Breach of Fiduciary Duty—Gist of the Action Doctrine—Extrinsic and Parol Evidence—Evidence of Motive<br />

1. A mere coalescence of votes of individual stockholders with equal standing whose shares cumulatively constitute a majority<br />

is not necessarily sufficient to suggest an abuse of controlling influence that is the essence of a breach of fiduciary obligations owed<br />

to a minority shareholder.<br />

2. Because Plaintiffs claim of breach of fiduciary duty is premised solely upon the assertion that the defendants breached the<br />

Stock Restriction Agreement (“SRA”), his argument presupposes a breach of the SRA by defendants. The gist of the action doctrine<br />

precludes recasting breach of contract claims into tort actions.<br />

3. Individual defendants barred supervision of a sales territory by an employee of a competitor and rejected the nomination of<br />

a Qualified Replacement Shareholder (“QRS”) based upon concerns of alienation of, or possible litigation by, a customer was sufficient<br />

to defeat claim of breach of fiduciary duty.<br />

4. The contract language presented an ambiguity and the court acquired extrinsic or parol evidence to assist in resolving the<br />

ambiguity. The Court, as a matter of law, determines the existence of an ambiguity and interprets the contract. The resolution of<br />

conflicting parol evidence relevant to what the parties intended by the ambiguous provision is for the trier of fact.<br />

5. The goal in contract law is not to punish the breaching party, but to make the nonbreaching party whole; proof of a financial<br />

motive or even an illicit motive will not enlarge damages. Therefore, the Court did not err in denying the admission of evidence of<br />

the compensation paid to the individual defendants and the salesman who replaced Plaintiff.<br />

(JoAnn F. Zidanic)<br />

Stephen D. Wicks for Plaintiff.<br />

Thomas M. Castello for Defendant.<br />

No. GD 07-012408. In the Court of Common Pleas of <strong>Allegheny</strong> <strong>County</strong>, Pennsylvania, Civil Division.<br />

OPINION<br />

McCarthy, M., November 23, 2009—Plaintiff, Neal R. Grove, appeals in this matter following a judgment taken on a jury verdict<br />

that found against Grove on a breach of contract claim brought by Grove against the defendants. Grove and the three (3) individual<br />

defendants are the original and only shareholders of the corporate defendant, Sales Marketing Group. Because all shareholders<br />

own equal shares of the common stock of Sales Marketing Group, the individual defendants, cumulatively, possess a majority<br />

of the common stock; Grove asserts that, in this instance, he is a minority shareholder.<br />

The three (3) individual defendants are also employees of the Sales Marketing Group. Grove is a former employee. The corporation<br />

is engaged in independent representation of electrical manufacturers, cultivating sales for various manufacturing lines. As<br />

an employee of the corporation, Grove managed a sales territory in central Pennsylvania.<br />

On November 15, 1994, at the inception of the business, all four (4) shareholders, together with the corporation, entered into a<br />

Stock Restriction Agreement (“SRA”). Article VI of the SRA addresses the matter of a shareholder terminating employment with<br />

Sales Marketing Group, whether by reason of permanent disability or by reason of a shareholder’s election to terminate following<br />

completion of ten (10) years of employment with Sales Marketing Group. Article VI states, in part:<br />

VI. Disability and Normal Retirement<br />

A. In the event a Shareholder terminates his employment with the Corporation due to said Shareholder’s permanent disability<br />

or following his completion of ten (10) years of employment with the Corporation and/or its predecessor entity, the<br />

terminated Shareholder shall be permitted to sell his Stock to a “Qualified Replacement Shareholder” (QRS) pursuant to<br />

the following terms and conditions:<br />

1. A QRS shall be an individual who has been approved to assume the duties of the terminated Shareholder by all of<br />

the remaining Shareholders, whose approval shall not be unreasonably withheld.<br />

2. The QRS and the terminated Shareholder shall enter into a contract for the sale of the terminated Shareholder’s<br />

Stock. The contract terms shall provide for a division of the terminated Shareholder’s future compensation from the<br />

Corporation between the terminated Shareholder and the QRS. It is intended that the division of compensation shall<br />

continue for five (5) years. The contract must be approved by all of the remaining Shareholders, whose approval shall<br />

not be unreasonably withheld. The terminated Shareholder shall be responsible for the supervision of the QRS and for<br />

transferring responsibility for his accounts to the QRS.<br />

In April 2006, Defendant Robert L. Smith, the President of Sales Marketing Group, received information from Grove that another<br />

employer, Hubbell Corporation, a competitor of Sales Marketing Group, had made an offer of employment to Grove. Shortly<br />

thereafter, and effective May 31, 2006, Grove terminated his employment with Sales Marketing Group. On June 13, 2006, Grove<br />

submitted the name of Justin Irvin to the individual defendants for approval as a Qualified Replacement Shareholder (“QRS”).<br />

Following an interview of Irvin, the individual defendants declined to approve or disapprove Irvin as a QRS. Subsequently, by<br />

means of an unsigned document appearing on corporate letterhead and dated July 17, 2006, Grove learned of specific reservations<br />

regarding approval of Irvin as a QRS. Among those expressed reservations was that Grove’s employment by a competitor would<br />

preclude supervision of Irvin by Grove, that Irvin lacked pertinent experience and that, because Irvin was a newer employee of a<br />

current customer of Sales Marketing Group and because that customer had contributed significantly toward Irvin’s college education,<br />

“repercussions” might result from acceptance of Irvin as a QSR.<br />

Also on or about July 17, 2006, Grove received a document setting forth “Supervision Requirements” to be observed by him in<br />

connection with the acceptance of a QSR. Grove refused to accept those supervision requirements. Thereafter, by letter dated<br />

October 5, 2006, Attorney Richard Brabender 1 advised plaintiff’s counsel that the individual defendants regarded “the provisions<br />

of Article VI [of the SRA] regarding normal retirement [as] irrelevant because Mr. Grove did not retire.” (Complaint, Exhibit B).<br />

Subsequently, negotiations for alternative evaluations having failed, defendants deemed Grove to be entitled solely to the book

page 156 volume 158 no. 9<br />

value of his shares in the corporation pursuant to provisions of the SRA relating to termination of employment for reasons other<br />

than retirement or disability.<br />

Grove thereafter filed a two-count complaint in civil action asserting, as to all defendants, breach of contract and, as to the<br />

individual defendants only, breach of fiduciary duty. The breach of contract action was predicated upon an alleged unreasonable<br />

failure to approve as a QRS the individual with whom plaintiff had purportedly contracted to sell his stock. (Complaint, at<br />

Paragraphs 25-30). The breach of fiduciary duty count averred that the individual defendants, as majority shareholders, owed a<br />

fiduciary obligation to Grove and that, “as a result of their desire to reduce the number of owners in the corporation and secure<br />

for themselves a greater share of the profits,” those defendants failed to comply with the terms of Article VI of the SRA.<br />

(Complaint, at 33-34)<br />

The matter eventually proceeded to trial before a jury. At the conclusion of plaintiff’s case, upon the motion of defendants, the<br />

Court dismissed the claim for breach of fiduciary duty. At the conclusion of all testimony and argument, the jury received a verdict<br />

slip jointly approved by the parties, and, following deliberations, found against Grove on the breach of contract claim. Grove<br />

now appeals, asserting that the Court erred in the dismissal of the claim for breach of fiduciary duty, in refusing certain of Grove’s<br />

proposed points for charge, and in certain evidentiary rulings that, Grove maintains, affected the jury’s construction of the SRA,<br />

resulting in an improper verdict.<br />

Breach of Fiduciary Duty<br />

Because majority shareholders occupy a quasi-fiduciary relation toward a minority shareholder, they may not use their power<br />

in such a way as to exclude the minority from a proper share of the benefits accruing from the enterprise. See, Ferber v. American<br />

Lamp Corp., 503 Pa. 489, 469 A.2d 1046 (1983); Hornsby v. Lohmeyer, 364 Pa. 271, 275; 72 A.2d 294, 298 (1950). This does not mean<br />

that majority shareholders may never act in their own interest. When, however, such shareholders act in their own interest, their<br />

actions must be also in the best interest of all shareholders and the corporation. Weisbecker v. Hosiery Wide Patents, Inc., 356 Pa.<br />

244, 251, 258, 51 A.2d 811, 814, 817 (1947). Grove contends in this matter that the individual defendants abused their majority<br />

standing “by failing to comply with the provisions of Article VI [of the SRA] which permit Plaintiff to sell his shares in the corporation<br />

to the QRS.” Complaint at 26.<br />

The SRA requires unanimous approval of remaining shareholders before any QSR proposed by a departing shareholder will be<br />

accepted. Grove appears to presume that, because Irvin was not approved as a QSR, the individual defendants acted in concert to<br />

reject Irvin, to the detriment of Grove. A mere coalescence of votes of individual stockholders with equal standing whose shares<br />

cumulatively constitute a majority is not necessarily sufficient to suggest an abuse of controlling influence that is the essence of a<br />

breach of fiduciary obligations owed to a minority shareholder. A group of shareholders ordinarily cannot use its control over the<br />

corporation to provide benefits to the majority that are not shared with the minority. However, the record in this case indicated<br />

neither any past pattern of corporate control by the individual defendants to the exclusion of Grove nor any joint pursuit by them<br />

in this particular matter of a disparate application of the SRA to Grove. The defendants merely sought to hold Grove to the requirements<br />

of a contract that they believed that they and Grove, all as equally situated individuals, had crafted and executed at the<br />

inception of their enterprise, and to which all would be held equally. That Grove disagreed with and was damaged by that construction<br />

of the SRA in this instance did not convert a contractual dispute into a claim of a breach of a fiduciary relationship. The dispute<br />

is contractual; the shareholder cannot legitimately complain about discriminatory treatment if he assented to an agreement<br />

that arguably provided for that treatment.<br />

Additionally, because Grove’s claim of breach of fiduciary duty is premised solely upon the assertion that the defendants<br />

breached the SRA, his argument presupposes a breach of the SRA by defendants. In that regard, the SRA being central to the dispute,<br />

it is difficult to look past the gist of the action doctrine, which precludes recasting breach of contract claims into tort actions.<br />