Mobile Tradition live - BMW Car Club Brasil

Mobile Tradition live - BMW Car Club Brasil

Mobile Tradition live - BMW Car Club Brasil

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

History moves with us<br />

<strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> <strong>live</strong><br />

Facts and background<br />

Facts<br />

The most important events, dates and<br />

anniversaries in the coming months.<br />

Page 03-06<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> 303<br />

The first six-cylinder car in <strong>BMW</strong> history<br />

also launched <strong>BMW</strong>’s “kidney grille”.<br />

Page 08-11<br />

Parts<br />

Spare parts are crucial for cars, but often<br />

difficult to track down for classic models.<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> offers assistance. Page 12-15<br />

Paul Rosche<br />

The “engine guru” is one of the legends<br />

of racing engine design.<br />

A profile. Page 16-18<br />

To Tehran with 12 bhp<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> motorcycles have traditionally been<br />

robust. Two students proved this in 1956<br />

by riding to Iran on two wheels.<br />

Page 20-23<br />

Anniversaries in the year 2003<br />

90 years<br />

80 years<br />

75 years<br />

30 years<br />

25 years<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> Group<br />

<strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong><br />

Founding of the Rapp<br />

Motorenwerke GmbH<br />

<strong>BMW</strong>’s first motorcycle is<br />

unveiled in Berlin<br />

Takeover of the Eisenach<br />

car factory<br />

New <strong>BMW</strong> plant opens<br />

in Dingolfing<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> M1 production launch<br />

20 years Victory in the Formula One<br />

World Championship<br />

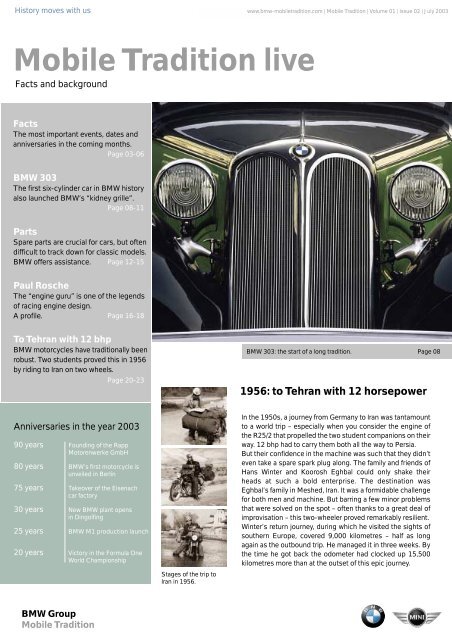

Stages of the trip to<br />

Iran in 1956.<br />

www.bmw-mobiletradition.com | <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> | Volume 01 | Issue 02 | July 2003<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> 303: the start of a long tradition. Page 08<br />

1956: to Tehran with 12 horsepower<br />

In the 1950s, a journey from Germany to Iran was tantamount<br />

to a world trip – especially when you consider the engine of<br />

the R25/2 that propelled the two student companions on their<br />

way. 12 bhp had to carry them both all the way to Persia.<br />

But their confidence in the machine was such that they didn’t<br />

even take a spare spark plug along. The family and friends of<br />

Hans Winter and Koorosh Eghbal could only shake their<br />

heads at such a bold enterprise. The destination was<br />

Eghbal’s family in Meshed, Iran. It was a formidable challenge<br />

for both men and machine. But barring a few minor problems<br />

that were solved on the spot – often thanks to a great deal of<br />

improvisation – this two-wheeler proved remarkably resilient.<br />

Winter’s return journey, during which he visited the sights of<br />

southern Europe, covered 9,000 kilometres – half as long<br />

again as the outbound trip. He managed it in three weeks. By<br />

the time he got back the odometer had clocked up 15,500<br />

kilometres more than at the outset of this epic journey.

Editorial<br />

Page 02<br />

Dear Readers,<br />

When the first edition of <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> <strong>live</strong> landed on our desks hot off<br />

the press, we were admittedly a tiny bit proud. We had hoped for a little<br />

praise from you, but would never have dreamed of such a positive<br />

response. It has reinforced our commitment towards the continuing<br />

advancement of <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> <strong>live</strong>.<br />

The last three months have been a very eventful time. Techno Classica,<br />

Europe’s premier classic car show, notably set the pulses of aficionados<br />

racing once again. On display at the <strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> stand was a great deal of what<br />

makes up the fascination which this subject exerts on friends of the <strong>BMW</strong> brand. From our point of<br />

view, the primary aim was being able to communicate with you. Thus several discussion rounds<br />

provided an opportunity to talk about the key issues revolving around heritage cultivation. Particular<br />

attention was devoted to parts supply, which is, after all, one of the crucial components of classic<br />

model upkeep today and an area to which <strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> is strongly committed.<br />

From our own experience of looking after our vehicle collection, we know only too well the indispensable<br />

role played by expertise and the availability of spare parts in safeguarding the enjoyment<br />

of historical models – reason enough to present this theme, starting on page 12, as the main focus<br />

of the current edition of <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> <strong>live</strong>.<br />

We also have a special contribution lined up for our motorcycle devotees: a report on an adventurous<br />

trip from Germany to Iran on a 1950s <strong>BMW</strong> R 25/2. Get geared up for plenty of excitement along<br />

the way!<br />

Here’s wishing you a pleasant journey into the living past.<br />

Read and enjoy!<br />

Holger Lapp<br />

Holger Lapp, Director of <strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong><br />

Contents Issue 02.2003<br />

Dates, facts, anniversaries:<br />

News and events not to be missed Page 03<br />

The Rail Zeppelin:<br />

Record ride with aero-engine technology by <strong>BMW</strong> Page 07<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> 303:<br />

The first six-cylinder car from <strong>BMW</strong> Page 08<br />

From the Isetta to the Z1:<br />

Parts sale and service by <strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> Page 12<br />

Paul Rosche:<br />

Engine guru and down-to-earth Bavarian Page 16<br />

To Tehran with 12 horsepower:<br />

Two Germans ride to Persia in 1956 on a <strong>BMW</strong> R25/2 Page 20<br />

<strong>BMW</strong>’s first six-cylinder for a car was mounted in<br />

the <strong>BMW</strong> 303.<br />

Publication details<br />

Responsible: Holger Lapp<br />

(see below for address)<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong><br />

Schleißheimer Straße 416 / <strong>BMW</strong> Allee<br />

80935 Munich<br />

www.bmw-mobiletradition.com

Dates and events<br />

July 2003 August 2003<br />

3 to 6 July 2003 /<br />

Montafon (A)<br />

Silvretta Classic<br />

Historic Alpine rally<br />

through the Austrian<br />

massif.<br />

4 to 6 July 2003 /<br />

Garmisch-<br />

Partenkirchen (D)<br />

3 rd International Bikers´<br />

Meeting<br />

Exhibition and rally – a<br />

must for fans of historic<br />

two-wheelers.<br />

Facts Fakten Faits Fatti<br />

Mille Miglia 2003<br />

Brescia. Series winner <strong>BMW</strong> rolled up for<br />

this year’s edition of the Mille Miglia with<br />

royal support: King <strong>Car</strong>l Gustav of Sweden<br />

was at the wheel of a <strong>BMW</strong> 328 Mille Miglia<br />

Touring contesting this classic rally that<br />

leads from Brescia via Ferrara to Rome and<br />

back to Brescia. The highly traditional<br />

event, first staged 76 years ago, runs<br />

through the marvellous landscapes of<br />

northern and central Italy, drawing hundreds<br />

of thousands of spectators to the<br />

roadside. Eligible for participation are models<br />

which have competed in the classic<br />

Mille Miglia at least once between 1927<br />

and 1957. This year’s event took place<br />

from 22nd to 25th May. Last year the Mille<br />

Miglia counted 370 entrants.<br />

Apart from King <strong>Car</strong>l Gustav of<br />

Sweden with his co-driver Prince Leopold<br />

of Bavaria, there were a further 21 <strong>BMW</strong><br />

teams lining up for the race with a total of<br />

nine cars from <strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong><br />

<strong>Tradition</strong> and 13 private <strong>BMW</strong>s. The<br />

majority of these participants were in<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> 328s, including historically significant<br />

models such as the <strong>BMW</strong> 328 Mille<br />

11 to 13 July 2003 /<br />

Goodwood (GB)<br />

Goodwood Festival of<br />

Speed<br />

Exhibition and races on the<br />

site of famous historic<br />

events and the new Rolls-<br />

Royce plant.<br />

19 to 27 July 2003 /<br />

Germany (D)<br />

2,000 km through<br />

Germany<br />

<strong>Tradition</strong>al classic car rally.<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong>: Dates & Facts<br />

13 to 17 August 2003 /<br />

Zwickau-Dresden (D)<br />

1 st Saxony Classic<br />

Vintage rally through<br />

Saxony with an anticipated<br />

150 classic cars participating.<br />

Miglia Roadster. The absolute highlight<br />

was the triumphant car of the 1940 Mille<br />

Miglia, a <strong>BMW</strong> 328 Mille Miglia Coupé<br />

with bodywork by Touring. In 1940,<br />

Huschke von Hanstein with co-driver<br />

Walter Bäumer had steered this aerodynamic<br />

racer along the 1,503-kilometre<br />

course in a record time of eight hours, 54<br />

minutes and 46 seconds to cross the finishing<br />

line in Brescia as winners. Apart<br />

from the contingent of <strong>BMW</strong> 328s, there<br />

was also a <strong>BMW</strong> 507, a Veritas, and even a<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> Isetta participating in the race. Rock<br />

star Gianna Nannini drove a <strong>BMW</strong> 327<br />

Cabriolet. For the spectators, it offered<br />

another exciting cross-section of <strong>BMW</strong>’s<br />

sporting past in action on the road.<br />

Overall victory went to the Sielecki –<br />

Hervas team of Argentina in a Bugatti T<br />

23 Brescia. The women’s category was<br />

won by the <strong>BMW</strong> team of Boni – Barziza<br />

driving a <strong>BMW</strong> 328, while the constructors’<br />

trophy was taken by Fiat, with <strong>BMW</strong><br />

in ninth place. Further information at<br />

http://www.millemiglia.it/news2003/<br />

mm2003.htm.<br />

September 2003<br />

4 to 7 September 2003 /<br />

La Roche (B)<br />

41 st annual meeting of<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> <strong>Club</strong> Europa<br />

New internet presence<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> launched its<br />

new internet presence in April 2003. All key<br />

information relating to the theme of “<strong>BMW</strong><br />

<strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong>” can be accessed here.<br />

Each area of competence of the heritage<br />

division is introduced, along with its particular<br />

tasks. The Historical Archives, for<br />

example, not only allow internet users<br />

access to the archives´ search machine,<br />

but also enable them to download the<br />

order form to apply for an official certificate<br />

for a historical model.<br />

Further highlights are the Historical<br />

Collection and the self-drive car hire programme.<br />

Anyone interested in hiring a car<br />

can obtain all the information necessary<br />

to get behind the steering wheel of one of<br />

our historical models.<br />

For owners of classic models, the<br />

online parts catalogue is an indispensable<br />

and convenient aid to tracking down<br />

spare parts.<br />

Why not click by some time!<br />

www.bmw-mobiletradition.com<br />

www.historicalarchive.bmw.com<br />

<strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> <strong>live</strong> / Issue 02.2003 Page 03

Facts Fakten Faits Fatti<br />

Review Techno Classica 2003<br />

Munich/Essen. Techno Classica, held in<br />

Essen and for years the most important<br />

gathering place for fans of classic vehicles<br />

at the start of the season, was another<br />

resounding success this year.<br />

Notwithstanding the general economic<br />

downturn and the war in Iraq, the show<br />

proved an even bigger draw than before,<br />

having rarely seen so many visitors over<br />

its four-day duration. In all, 109,000<br />

experts and aficionados turned up.<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> again played<br />

a key role in the success of the event. Hall<br />

12, arranged in conjunction with the <strong>BMW</strong>,<br />

MINI, Rolls-Royce and Glas brand clubs,<br />

as well as the Veritas register and the<br />

Eisenach car museum, even drew words<br />

of praise from the competition. The <strong>BMW</strong><br />

Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> stand was dedicated<br />

primarily to the theme of convertibles<br />

against a delightful mountain backdrop, as<br />

well as placing special emphasis on<br />

<strong>BMW</strong>’s anniversaries “80 Years of <strong>BMW</strong><br />

Motorcycles”, “25 Years of the <strong>BMW</strong> M1”<br />

and “20 Years of the Formula One<br />

Championship”.<br />

Goodwood. Next to the Mille Miglia and<br />

the Concorso d’Eleganza Villa d’Este, the<br />

Festival of Speed held in Goodwood in<br />

southern England ranks among the top<br />

events in the 2003 classic calendar for<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong>. To mark<br />

the Festival’s tenth anniversary, the heritage<br />

department of the <strong>BMW</strong> Group will<br />

be present again with an array of treasures<br />

from its Historical Collection. From<br />

11th to 13th July 2003, <strong>BMW</strong> motorcycles<br />

as well as sports and racing cars will<br />

be out on the race track of the historic<br />

grounds of Goodwood House, driven by<br />

big names from the world of motorsport.<br />

The Goodwood Festival of Speed<br />

enjoys an outstanding reputation among<br />

motor racing fans. This is the only venue<br />

where spectators can experience 100<br />

years of racing history in action. After<br />

drawing crowds of 25,000 in 1993, its<br />

inaugural year, 2002 saw more than<br />

130,000 visitors flocking to witness<br />

motorcycles and sports cars of all classes<br />

and ages battling for the best times on<br />

the 1.2-mile circuit.<br />

Page 04<br />

As always, the<br />

theme of “Parts<br />

and Service” with<br />

highly informative<br />

exhibits attracted<br />

keen interest.<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> Group<br />

<strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong>’s<br />

presence was complemented<br />

by a<br />

press conference in<br />

the form of a discussion<br />

round, as<br />

well as two further<br />

rounds of talks. In<br />

the first, the heads<br />

of the heritage divisions<br />

of Daimler<br />

Chrysler, Audi,<br />

Porsche and <strong>BMW</strong><br />

discussed the significance of heritage cultivation<br />

for their respective companies and<br />

customers.<br />

In the second discussion round, representatives<br />

of supplier companies<br />

talked about the problems of supplying<br />

Three anniversaries form the core of<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong>’s activities<br />

in 2003. The Festival of Speed provides<br />

the perfect setting for celebrating “20<br />

years of the Formula One Championship“,<br />

exemplified by the Brabham BT 52 –<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> F1 in which Nelson Piquet won the<br />

championship in 1983 and the latest<br />

WilliamsF1 <strong>BMW</strong> FW25, driven by Juan<br />

Pablo Montoya.<br />

The appearance of a <strong>BMW</strong> M1 Procar<br />

represents the racing history of this outstanding<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> sports car launched 25<br />

years ago. In addition, numerous <strong>BMW</strong><br />

motorcycles will be in action, bearing witness<br />

to the Munich company’s 80-year<br />

tradition of two-wheeled production.<br />

Apart from the cars and motorcycles<br />

out on the race track in 2003, a broad<br />

selection of models will also be on display<br />

in the <strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> pavilion.<br />

A range of accessories for sale will<br />

round off the attractions laid on for visitors<br />

to the Goodwood Festival of Speed.<br />

Further information about the event can<br />

be found at www.goodwood.co.uk.<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong>’s stand at Techno Classica in Essen:<br />

Bavarian flair in Germany’s former industrial heartland.<br />

parts for historical models. Both discussions<br />

were transmitted <strong>live</strong> into the exhibition<br />

hall. They are also being streamed<br />

on the internet for several months at the<br />

following address:<br />

www.auto-managerTV.com.<br />

Goodwood Festival of Speed 2003 Silvretta Classic 2003<br />

Montafon. Few regions of Europe offer<br />

such a stunning panorama for a classic<br />

car event as the Montafon valley in<br />

Austria. The Silvretta Alpine road takes<br />

you up to a grand altitude of more than<br />

2,000 metres above sea level. Twisty,<br />

stunning mountain roads alternate with<br />

picturesque Alpine valleys to make up the<br />

spectacular scenery for an exceptional<br />

classic rally.<br />

From 3rd to 6th July 2003, owners of<br />

some 150 cherished four-wheeled classics<br />

will be able to savour this wonderful<br />

landscape and the welcoming Montafon<br />

region.<br />

The course covers around 450 kilometres<br />

divided into three daily stages.<br />

During these, participants have to complete<br />

a total of 16 classification trials, 18<br />

time checks and four transit controls.<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> will once<br />

again be involved in the Silvretta Classic<br />

with a wide range of historical cars,<br />

including, for example, a <strong>BMW</strong> 507<br />

Roadster taken from its collection of<br />

some 400 classic four-wheelers.

Anniversaries in <strong>BMW</strong>´s corporate history<br />

90 years<br />

Founding of the Rapp Motorenwerke<br />

On the northern edge of the Oberwiesenfeld, Munich’s first airfield,<br />

Karl Rapp and Julius Auspitzer founded the Karl Rapp<br />

Motorenwerke GmbH on 28th October 1913. Located on the<br />

site of the recently liquidated Flugwerke Deutschland GmbH,<br />

the new company was designed to manufacture and distribute<br />

“engines of all kinds, in particular internal combustion engines<br />

for aircraft and motor vehicles”. The sole shareholder of the<br />

engine construction company was Consul General Auspitzer.<br />

Karl Rapp ran the business operation.<br />

Several aero-engine prototypes were designed at the Rapp<br />

works, none of which, however, made it into production due to<br />

structural weaknesses. In July 1917, the facilities, patents and<br />

company site were incorporated into the Bayerische Motoren<br />

Werke GmbH, and the Rapp Motorenwerke were subsequently<br />

closed.<br />

80 years<br />

<strong>BMW</strong>’s first motorcycle unveiled in Berlin<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> first presented its R 32 at the Berlin Motor Show held from<br />

28th September to 3rd October 1923. This is not exactly a new<br />

discovery, yet there is ongoing confusion regarding this event<br />

since the majority of sources cite Paris as the birthplace of<br />

<strong>BMW</strong>’s motorcycle heritage. Just how this Parisian myth was<br />

debunked reads a bit like a detective story.<br />

The fact is that, for decades, the Paris Motor Show which<br />

took place at the beginning of October was named as the launch<br />

venue. The first source in question is an unpublished text marking<br />

the 20th anniversary of <strong>BMW</strong> motorcycles.<br />

In an interview with Rudolf Schleicher, who in 1923 was<br />

working out plans for the production launch of the R 32, he mentioned<br />

that the R 32 had been unveiled in Paris. That seemed to<br />

indicate beyond doubt that the debut of the R 32 must have<br />

taken place in Paris, and that assertion was subsequently not<br />

called into question.<br />

In the run-up to the 75th anniversary of <strong>BMW</strong> motorcycles,<br />

extensive research was carried out in the archives and library of<br />

the Deutsches Museum in Munich. The first surprise was that<br />

there were numerous mentions of the R 32 being presented in<br />

Berlin, and of this motor show having already opened its doors<br />

on 28th September. A glance at the list of exhibitors and reviews<br />

of the event in the motoring press definitively supported this.<br />

It was thus clear that <strong>BMW</strong> had first presented the R 32 in<br />

Berlin, yet it was still possible that the motorcycle had also<br />

appeared at the Paris show.<br />

The de<strong>live</strong>ry book records that two motorcycles had initially<br />

been sent to the Berlin Motor Show before being passed on to<br />

a Berlin dealer for sale. No mention was made of Paris, however.<br />

Research undertaken by colleagues at <strong>BMW</strong> France similarly<br />

failed to unearth any mention of Paris. Unfortunately no extant<br />

catalogue of exhibitors at the Paris Motor Show could be found,<br />

not even in the National Library of Paris. That would have pro-<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong>: Anniversaries<br />

vided the crucial missing piece of the jigsaw puzzle that could<br />

have shed light on the matter. The search for it had virtually<br />

been abandoned when the archivists at DaimlerChrysler Classic<br />

mentioned that they had a copy of the very catalogue. A subsequent<br />

search showed that <strong>BMW</strong> had not been registered as an<br />

exhibitor.<br />

This provided the ultimate proof that the debut of the R 32<br />

had, for decades, been erroneously attributed to Paris rather<br />

than Berlin.<br />

75 years<br />

Takeover of the Eisenach car factory<br />

The “new” <strong>BMW</strong> AG had been established in 1922 by Austrian<br />

financier Camillo Castiglioni to include the “manufacture of automobiles”<br />

as well. Attempts to develop and build cars, however,<br />

were not systematically carried out in the years that followed and<br />

ultimately remained uncompleted.<br />

In 1928, <strong>BMW</strong> had a surprising and excellent opportunity to<br />

gain a foothold in the flourishing car market through the purchase<br />

of the Eisenach car factory, also known as the DIXI-Werke. Only<br />

the previous year, the factory had concluded a licensing contract<br />

with the Austin Motor Company allowing them to manufacture<br />

the successful small Austin Seven for the German market.<br />

For this purpose, the factory facilities were adapted to<br />

“assembly-line production” – a revolutionary method for the<br />

time. Thus on 28th October 1928, at a cost of 1 million reichsmarks,<br />

the greater part payable in shares, <strong>BMW</strong> acquired a modernized<br />

automobile factory which was turning out an attractive<br />

and affordable small car. It was the perfect entry into the world of<br />

car manufacturing.<br />

30 years<br />

New <strong>BMW</strong> plant opens in Dingolfing<br />

Following the takeover of Hans Glas GmbH in Dingolfing in 1967,<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> AG transferred some of its car manufacturing facilities from<br />

Munich to its Lower Bavarian subsidiary in 1968. It soon became<br />

clear, however, that the capacities there would not be adequate for<br />

the planned expansion of car production.<br />

Over a period of three years, therefore, a second <strong>BMW</strong> plant<br />

was erected on a site of some 600,000 square metres in the direct<br />

vicinity of the first Dingolfing factory. The official opening of the<br />

production facilities took place on 22nd November 1973 in the<br />

presence of numerous guests of honour. By this time, the new<br />

Plant 2.4 had already proved its efficiency: just two months previously,<br />

<strong>BMW</strong>’s production director Hans Koch had taken de<strong>live</strong>ry of<br />

the first car to emerge from the new factory – a red <strong>BMW</strong> 520.<br />

Chronology of the Dingolfing plant:<br />

02 Jan 1967: Takeover of Hans Glas GmbH<br />

01 Jan 1968: Component production for cars and motorcycles<br />

09 Nov 1970: Cornerstone ceremony with Alfons Goppel<br />

27 Sep 1973: First car comes off the production line<br />

22 Nov 1973: Official opening of Plant 2.4<br />

<strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> <strong>live</strong> / Issue 02.2003 Page 05

Anniversaries / <strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> overview<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> M1 production launch<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> unveiled its new high-performance <strong>BMW</strong> M1 sports car at<br />

the Paris Motor Show on 5th October 1978. Under the direction<br />

of racing driver Jochen Neerpasch, the newly-fledged <strong>BMW</strong><br />

Motorsport GmbH, in collaboration with several external partners<br />

including Lamborghini, had produced a racer which has lost none<br />

of its fascination to this day.<br />

Though it was conceived as a base vehicle for motor racing,<br />

this objective was only met to a limited extent since setbacks<br />

in its development delayed production readiness and<br />

with it the hoped-for homologation. But the Procar race series,<br />

specially launched for the <strong>BMW</strong> M1 and involving the best<br />

Formula One drivers in identical M1s battling for victory, will<br />

remain unforgotten.<br />

Even 25 years after its debut, the street version of the <strong>BMW</strong><br />

M1 with 277 bhp and weighing just 1,300 kg, of which only 401<br />

units were built up to 1981, still ranks among the most dynamic<br />

sports cars of all time. Long since established as a classic of<br />

recent motoring history, most of the <strong>BMW</strong> M1 mid-engine<br />

sports cars have survived to the present under the solicitous<br />

care of devotees of extraordinary automobiles.<br />

Page 06<br />

25 years 20 years<br />

Victory in the Formula One World Championship<br />

“A sensational triumph for <strong>BMW</strong> and Brabham at the World<br />

Championship final in South Africa on 15th October 1983” ran<br />

the exultant banner headline that marked the beginning of<br />

<strong>BMW</strong>’s very own chapter in the history of Formula One.<br />

The success of the team, which was made up of British and<br />

Bavarian members, was the crowning endorsement of the commitment<br />

with which <strong>BMW</strong> had entered the top echelon of motor<br />

racing.<br />

Behind this triumph were a raft of famous names including,<br />

for example, Bernie Ecclestone, Gordon Murray, Paul Rosche<br />

and, of course, Nelson Piquet, the man behind the wheel of the<br />

victorious car.<br />

The first Formula One World Championship title in the history<br />

of the Bavarian company was made possible by a vehicle<br />

driven by a powerful <strong>BMW</strong> turbo engine which was outstanding<br />

for the time. Thanks to superior powertrain technology, the<br />

prized crown of motorsport thus went to a German car manufacturer<br />

again – the Bayerische Motoren Werke of Munich – for<br />

the first time since the championship victories claimed by the<br />

legendary Silver Arrows of Mercedes-Benz.<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> areas of competence<br />

Archives Parts and Accessories Vehicle collection<br />

This is where all information relating to<br />

the history of the company, its brands and<br />

its products is gathered and stored. The<br />

Archives are the main port of call for all<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> departments requiring historical<br />

information of any kind.<br />

The same goes for journalists, writers,<br />

historians and all those interested in<br />

the heritage of the <strong>BMW</strong> Group and its<br />

products. Research can be carried out<br />

from home via the internet by logging<br />

onto: www.historicalarchive.bmw.com<br />

The <strong>BMW</strong> Museum presents the past,<br />

present and future of the <strong>BMW</strong> brand<br />

within the context of the relevant social<br />

and historical era. It was inaugurated in<br />

1973 as the first museum of its kind.<br />

Today, hundreds of thousands of visitors<br />

every year come to the museum’s changing<br />

exhibitions to learn about the <strong>BMW</strong><br />

company and experience the fascination<br />

of the <strong>BMW</strong> brand.<br />

This department guarantees a comprehensive<br />

supply of parts for the faithful<br />

restoration of <strong>BMW</strong> classics. 15 years<br />

after production has been phased out,<br />

owners of historical models are supplied<br />

with all the necessary spare parts, now<br />

numbering several tens of thousands in<br />

total. Repair guidelines are also provided<br />

for the models.<br />

At the heart of <strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong><br />

<strong>Tradition</strong> is the Historic Collection. It contains<br />

more than 400 cars and 170 motorcycles,<br />

as well as numerous aircraft,<br />

motorcycle and car engines, all the way to<br />

the latest Formula One power units. The<br />

involvement of these vehicles in numerous<br />

national and international events is<br />

overseen by the operations management<br />

department. Maintenance and restoration<br />

work on these classics is undertaken<br />

in the workshop of <strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong><br />

<strong>Tradition</strong>.<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> Museum <strong>Club</strong>s, events, communications<br />

Restoration job in the workshop of <strong>BMW</strong><br />

Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong>.<br />

Around the globe, <strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong><br />

<strong>Tradition</strong> takes part in events and exhibitions<br />

in the classic car and motorcycle<br />

scene, particularly those relating to the<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> Group’s past, such as Techno<br />

Classica in Essen, the Concorso<br />

d’Eleganza Villa d’Este or the Goodwood<br />

Festival of Speed. To this end, the division<br />

supports some 180 <strong>BMW</strong> clubs, stages<br />

numerous events of its own, and issues<br />

publications on <strong>BMW</strong>’s motoring heritage.

<strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong>: Aircraft Engines<br />

The Rail Zeppelin – record trip with<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> aero-engine technology<br />

It’s a highlight of any model railway set, and many regard it as the precursor of the Transrapid high-speed train. The enduring popularity of the Rail<br />

Zeppelin is remarkable considering that, after just a few hundred test kilometres, the world’s fastest track vehicle of the time was jettisoned for reasons<br />

of transport policy.<br />

by Fred Jakobs<br />

ed canvas. Driving it was now a 600 horsepower<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> VI aero-engine which, like the propeller, was<br />

tilted slightly upward to increase pressure on the rails.<br />

On 25th September 1930, the “Rail Zepp” set<br />

out on its maiden journey. On the short length of<br />

track, the 180 km/h mark was exceeded before the<br />

continuously accelerating train had to be slowed<br />

down and brought to a halt. In May 1931, the Rail<br />

Zeppelin then made its first journey on Germany’s<br />

regular rail network. Along a stretch of some 20 kilometres,<br />

it achieved a speed of 205 km/h, just below<br />

the record established in 1903, which continued to<br />

stand. It was nevertheless an encouraging result, and<br />

Kruckenberg was keen to test his invention over<br />

longer distances.<br />

The Rail Zeppelin on a test ride: “Like a vision from the distant future” was the On 21st June 1931, the Rail Zeppelin embarked<br />

headline in <strong>BMW</strong>’s in-house newsletter.<br />

on its legendary ride from the Hamburg district of<br />

Bergedorf to Berlin. The 257-kilometre distance was<br />

completed in a mere 98 minutes. Along a 12-kilometre section it<br />

reached 230 km/h to set up a new world record which endured for<br />

almost 25 years. The train subsequently travelled around Germany,<br />

attracting thousands of curious onlookers.<br />

Although the Rail Zeppelin had passed the acid test,<br />

Germany’s national railway remained sceptical. For one thing, a<br />

propeller drive was deemed too dangerous. For another, such a<br />

fast train would, with existing braking technology, be difficult to<br />

integrate into a railway network geared to a top speed of 120 km/h<br />

and into the established railway timetable. It was for these reasons<br />

that the concept was turned down and the project scotched. The<br />

record-breaking train itself was sent to the scrappers’ yard in<br />

1939, leaving the scale model versions as the only means of seeing<br />

the Rail Zeppelin travelling at full tilt today.<br />

Engineers had long pondered the possibility of high-speed<br />

trains. As early as 1903, a three phase powered railcar developed<br />

by AEG and Siemens recorded a speed of 210 km/h.<br />

However, as this vehicle’s output of 3,000 bhp required a disproportionately<br />

high amount of energy, the project was not pursued<br />

any further.<br />

Almost three decades later, engineer Franz Kruckenberg<br />

struck out on a different path. He floated the idea of a propellerdriven<br />

railcar – float being the operative word, as initial plans<br />

envisaged a suspension railway. But the project did not materialize<br />

as the costs of laying down new routes for it would have gone<br />

beyond any reasonable scope. And so Kruckenberg decided to<br />

demonstrate the advantages of sophisticated aerodynamics and<br />

systematic lightweight construction on conventional tracks to<br />

begin with.<br />

The first test vehicle was ready in 1929. Its purpose was to verify<br />

once again that the propeller-drive concept was workable. As a<br />

test track, a virtually straight, unused, eight-kilometre stretch of<br />

track between Hanover and Burgwedel was selected. In April 1929,<br />

the first test rides were launched with twin 230 bhp <strong>BMW</strong> IV aircraft<br />

engines driving the train. When the far from aerodynamically perfect<br />

vehicle logged a speed of 175km/h, Kruckenberg saw his concept<br />

endorsed and started work on the construction of a production<br />

version in collaboration with the Aerodynamic Research<br />

Institute in Göttingen.<br />

In 1930 the train was assembled in Hanover-Leinhausen and<br />

christened “Rail Zeppelin” by the workforce. Its framework comprised<br />

a skeleton of tubular steel covered with fireproof-impregnat-<br />

The Rail Zeppelin<br />

Year of construction 1931<br />

Unladen weight 18,600 kg<br />

Length 25.3 m<br />

No. of axles 2<br />

Wheelbase 19.6 m<br />

No. of passengers up to 40<br />

Engine <strong>BMW</strong> VI<br />

Displacement 46.9 l<br />

Output 580 bhp<br />

Consumption 71.5 l / 100 km Parked at Berlin’s Grunewald station<br />

following its record attempts.<br />

<strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> <strong>live</strong> / Issue 02.2003 Page 07

Launch of a long tradition<br />

70 years ago – <strong>BMW</strong> 303,<br />

the first six-cylinder model<br />

For the Bayerische Motoren Werke the <strong>BMW</strong> 303 was a revolutionary vehicle, not merely because it was powered by the first automobile six-cylinder<br />

engine in <strong>BMW</strong> history. It also featured several other important technical innovations, as well as sporting the very first <strong>BMW</strong> “kidney grille”.<br />

by Walter Zeichner<br />

With its first cars of the 3/15 PS und 3/20<br />

PS model range, <strong>BMW</strong> had bucked the<br />

trend of the economically straitened<br />

period of 1929 to 1933 and, unlike many<br />

other car manufacturers, launched a successful<br />

start to its automotive history.<br />

The tried and tested small cars built<br />

under licence from Austin, along with the<br />

Page 08<br />

extensively redesigned 3/20 PS, came<br />

off the Eisenach production lines in more<br />

than 23,000 copies by the time they<br />

were phased out in March 1933.<br />

However, by 1931 the decision had<br />

already been made not to limit production<br />

to the small car category but to<br />

develop a technically more sophisticated<br />

model powered by a small six-cylinder<br />

engine. This was part of a cooperative<br />

agreement between <strong>BMW</strong> and Daimler-<br />

Benz, which gave <strong>BMW</strong> the market segment<br />

below the 1.3-litre displacement<br />

capacity and Daimler the category above<br />

this class. Originally there were two proposals<br />

put forward for the engine of this

Cover picture from a <strong>BMW</strong> 303 brochure of 1933.<br />

new model. <strong>BMW</strong> engine constructor Max Friz had designed a<br />

state-of-the-art unit in which he aimed to apply numerous<br />

insights from his longstanding experience of aero-engine construction.<br />

Details such as an aluminium crankcase or overhead<br />

valves in the detachable cylinder head were only used in<br />

extremely high-performance engines at the time, and were<br />

accordingly costly to produce.<br />

At the other extreme Martin Duckstein, a former colleague<br />

of Max Friz who had in the interim moved from Munich to<br />

Eisenach as head of construction, designed a very simple sixcylinder<br />

unit that was cheap to produce. However, design<br />

details such as vertical valves, an engine block and cylinder<br />

head cover of grey-cast iron and a crankshaft with triple bearings<br />

were too reminiscent of the Opel 1.8-litre engine with a<br />

modest 32 bhp launched just a few months earlier.<br />

The route to the right engine<br />

By now it was the summer of 1932, and General Manager<br />

Popp wasn’t happy with either of the designs. He sought the<br />

opinion of his test director in Munich, Rudolf Schleicher. Max<br />

Friz’s design was naturally far too expensive and Duckstein’s<br />

engine, despite its lower manufacturing costs, was on the<br />

simple side – not exactly <strong>BMW</strong>-worthy. However, Schleicher<br />

was impressed with such basic concepts as uniting the<br />

crankcase and the cylinder block into a highly rigid grey-cast<br />

iron component.<br />

A design by Rudolf Schleicher and his colleague Karl<br />

Rech accordingly envisaged just such an engine block based<br />

on “the American design principle”, though even more rigid<br />

and featuring four crankshaft bearings. The valves, as in the<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> 3/20 PS, were naturally in overhead arrangement in the<br />

grey-cast iron cylinder head, and the air/fuel mixture preparation<br />

– unusually for a touring engine – was handled by twin<br />

Solex carburettors using the updraft principle.<br />

Fundamental principles of the building-block system – in<br />

this case, the possibility of using shared components and<br />

machine tools from the existing 3/20 PS four-cylinder – were<br />

applied, along with modern assembly methods using preassembled<br />

units, such as the crankshaft with its six connecting<br />

rods and pistons.<br />

Hans Nibel, head of development at Daimler-Benz and a<br />

good friend of <strong>BMW</strong>’s managing director Popp, was ultimately<br />

consulted as an impartial expert and invited to make the<br />

final decision. He unhesitatingly opted for the design by Rech<br />

and Schleicher, and with the help of this “midwifery” it subsequently<br />

went into series production as the precursor of all<br />

future six-cylinder car engines made by <strong>BMW</strong>.<br />

The chassis design for the car was completely new, and by<br />

virtue of its lightweight construction would point the way ahead<br />

for subsequent <strong>BMW</strong> models. Chief constructor Fritz Fiedler,<br />

who had joined <strong>BMW</strong> from Horch as recently as 1932, found a<br />

new chassis frame at <strong>BMW</strong> which had been developed in<br />

Eisenach but, with its complex design based on U-sections, did<br />

not meet his expectations in terms of the “lightweight construction<br />

principle”. Using only the basic design of this frame,<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong>: Automobiles<br />

he succeeded within a short space of time in developing out of<br />

it a chassis frame for <strong>BMW</strong>’s first six-cylinder model.<br />

It consisted of two A-shaped tubular side members with a<br />

circular section that converged towards the width of the engine<br />

and two box-shaped crossbeams in similarly hollow design,<br />

with the tubular side members producing a moment of resistance<br />

10 times higher. At the front end of the frame, the side<br />

members were taken through a further crossbeam which also<br />

Historical <strong>BMW</strong> advertisements<br />

<strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> <strong>live</strong> / Issue 02.2003 Page 09

The first <strong>BMW</strong> six-cylinder model<br />

served as a bracket for the<br />

front transverse leaf spring.<br />

The sections of the side<br />

members, moreover, tapered<br />

towards the rear since lower<br />

bending moments came into<br />

play here. Such a lightweight,<br />

low-slung frame, boasting<br />

exceptional torsional rigidity<br />

into the bargain, naturally<br />

offered considerable advantages<br />

compared with the<br />

heavy U-profile frame in common<br />

use at the time, and <strong>BMW</strong><br />

Munich filed for a patent on<br />

this design on 28th January<br />

1933. Particular attention was<br />

also devoted to the wheel suspensions in<br />

the design of this new car following open<br />

criticism of this crucial aspect in connec-<br />

tion with the previous 3/20 PS and 3/15<br />

PS models.<br />

At the front, a new swing axle with<br />

low wishbones and hydraulic dampers<br />

ensured precise control and stability of<br />

the steered wheels, while the rear featured<br />

the tried and tested principle of a<br />

rigid axle with quarter-elliptic leaf springs<br />

and lever-type shock absorbers. Initial<br />

The latest <strong>BMW</strong> models at the 1933 Berlin Motor Show.<br />

Page 10<br />

A front end that defines <strong>BMW</strong> cars to this day: the “kidney grille”.<br />

drive tests in 1932 confirmed that the<br />

new car bearing the development code<br />

303 and with a weight-output ratio of 27<br />

The first radiator to feature the “<strong>BMW</strong> kidney grille”, and a raft of technical<br />

innovations which inspired numerous future developments.<br />

kg per brake horsepower was not just<br />

<strong>live</strong>ly but also boasted positively safe and<br />

far from uncomfortable ride characteristics.<br />

The first “<strong>BMW</strong> kidney grille”<br />

The 30 bhp 1.2-litre engine with twin<br />

carburettors – the smallest six-cylinder in<br />

Germany at the time – was as powerful<br />

as it was flexible and smoothrunning.<br />

In its bodywork<br />

design, too, <strong>BMW</strong> struck out on<br />

new paths, and this model<br />

came to define the <strong>BMW</strong> look<br />

for cars of that decade – and<br />

beyond to the present in one<br />

particular detail.<br />

The body stylists designed<br />

a significantly more spacious<br />

superstructure for the new car,<br />

which claimed an overall<br />

increase in length of 70 cm. In<br />

its advertisements <strong>BMW</strong> still<br />

described the model 303 as a<br />

small car, but they were clearly<br />

well on the way to leaving this<br />

humble category behind.<br />

The bodywork designers at <strong>BMW</strong><br />

had lent the radiator cowling on the new<br />

model a particularly<br />

striking design. The<br />

large air intake on the<br />

front of the car was<br />

divided into two areas<br />

clearly separated by a<br />

bar and at an angle to<br />

one another. They were faintly reminiscent<br />

of two adjacent kidneys familiar<br />

from schematic illustrations of the inner<br />

organs of the human body. No other<br />

leading car manufacturer employed such<br />

a radiator design at the time, and the<br />

“kidney grille” became a distinctive identifying<br />

feature of <strong>BMW</strong> cars, remaining<br />

so to this day with very few exceptions.<br />

It was only later that the story<br />

evolved of the Bruchsal-based manufacturers<br />

of small roadster bodies, Gebrüder<br />

Ihle, having developed and “invented”<br />

this design for their sports car bodies fitted<br />

onto the Dixi and <strong>BMW</strong> 3/15 PS<br />

chassis. Evidence shows, however, that<br />

Ihle only began offering bodywork with<br />

“kidney grilles” from 1935, having previously<br />

used the unitary flat radiators in<br />

common use. Ihle had adopted this striking<br />

design from <strong>BMW</strong> rather than the<br />

other way around.<br />

Phaeton by special order<br />

In February 1933, <strong>BMW</strong> was able to<br />

present the first examples of the new<br />

303 model at the Berlin Motor Show. The<br />

superstructures for the saloon had been<br />

built at the Sindelfingen workshops of<br />

Daimler-Benz, who had already signed a<br />

cooperative deal with <strong>BMW</strong> for the con-

struction of bodies for the previous 3/20<br />

PS model. But this first design was<br />

regarded by many as still too angular and<br />

“old-fashioned”, as a result of which certain<br />

modifications were carried out<br />

before series production was launched<br />

in May. At the same time, further bodywork<br />

designs were prepared for a twoseater<br />

and four-seater cabriolet.<br />

Eventually these three variants were<br />

de<strong>live</strong>red to the first customers in<br />

April/May 1933, starting with chassis<br />

number 45001. The saloons with their<br />

price tag of 3,600 reichsmarks made up<br />

the majority of sales. Anyone wishing to<br />

buy the four-window cabriolet or the<br />

two-seater sports cabriolet had to pay an<br />

extra 800 and 1,000 reichsmarks<br />

respectively. Shortly after production<br />

launch, there was also the option of a<br />

roller roof saloon in which the entire central<br />

part of the fabric roof could be rolled<br />

back to open up.<br />

Bodywork by Daimler-Benz<br />

The tourer (phaeton) bodywork variant<br />

available for the earlier models was only<br />

built twice by special commission for the<br />

303, since it was now no longer really in<br />

keeping with the times. For the sum of<br />

3,080 reichsmarks, 74 customers<br />

ordered a <strong>BMW</strong> 303 chassis with all the<br />

drive units and then had special bodywork<br />

built by independent coachbuilders<br />

“A small quality car with powerful performance”<br />

Test report on the 1.2-litre six-cylinder <strong>BMW</strong> by R. Otte<br />

“We left Berlin in the morning and after four hours we had reached<br />

Schierke at the Brocken mountain. That’s a distance of 240 km. In normal<br />

traffic one can comfortably average 70 km in the new 1.2-litre <strong>BMW</strong>. This<br />

kind of performance will undoubtedly satisfy above-average demands.<br />

This small six-cylinder is simply outstanding – smooth, flexible and powerful<br />

– a real little luxury machine. And the transmission! The way the gears<br />

change, so lightly and gently as if the cogs were made of rubber. The sixcylinder<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> is well above average in the so-called small car category.”<br />

such as Gläser in Dresden, usually in<br />

two-seater sports car design.<br />

When it came to the colour scheme<br />

of these simply but fully equipped models,<br />

the saloon purchaser had a choice<br />

of blue, reddish-brown and grey, each<br />

with black mudguards. The more expensive<br />

sports cabriolet was only available<br />

in ivory with light brown mudguards, a<br />

silver-grey bonnet and light red or light<br />

blue leather upholstery, while the four-<br />

Top: the first test chassis frame for the <strong>BMW</strong> 303.<br />

Bottom: the new lightweight tubular frame design for<br />

the series.<br />

seater cabriolet came in black, green,<br />

grey and beige with darker-toned mudguards<br />

and upholstery and a bonnet to<br />

match the basic colour. Clearly great<br />

efforts were already being<br />

made to offer a wide range of<br />

individual choices, and one can<br />

easily imagine that road traffic in<br />

the 1930s was not dominated<br />

by monochrome bodywork.<br />

The bodies for the saloon<br />

and roller roof saloon continued<br />

to be supplied by Daimler-Benz<br />

in Sindelfingen, and this collaboration<br />

would be maintained<br />

until the phase-out of the successor<br />

models <strong>BMW</strong> 315 and<br />

319, which were only distinguishable<br />

from the 303 in<br />

details.<br />

It wasn’t until the new 326<br />

and 329 models were launched<br />

that the saloon bodies began to<br />

be supplied by Ambi-Budd in<br />

Berlin once more. In March<br />

1934, the <strong>BMW</strong> 303 underwent<br />

its final revision and was given<br />

the same body style, with funda-<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong>: Automobiles<br />

mentally redesigned air intakes on the<br />

bonnet, as its successor model <strong>BMW</strong><br />

315, which was already waiting in the<br />

wings.<br />

Up until the production launch of this<br />

34 bhp, 1.5-litre model, a further 809<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> 303 units with this body were built<br />

over a two-month period. <strong>BMW</strong> had not<br />

only marketed the 303 model as a small<br />

car, but in advertising was keen to<br />

describe it as a high-performance model.<br />

Foundation of success: the 1.2-litre six-cylinder<br />

engine with 30 bhp.<br />

When one considers its lightweight<br />

design and its engine, which provided<br />

the basic design for the subsequent, typical<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> six-cylinder engines, this<br />

assessment would appear by no means<br />

an overstatement.<br />

It was with this model that <strong>BMW</strong><br />

made the leap into the circle of manufacturers<br />

of high-quality, sporty, compact<br />

automobiles. Anyone who has the good<br />

fortune today, 70 years on, of owning and<br />

driving a <strong>BMW</strong> 303 can vouch for the<br />

ease and safety with which <strong>BMW</strong>’s first<br />

six-cylinder model can be guided even<br />

through today’s traffic.<br />

The driving seat of the <strong>BMW</strong> 303.<br />

<strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> <strong>live</strong> / Issue 02.2003 Page 11

From Isetta to Z1 – parts sale and service<br />

at <strong>BMW</strong> <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong><br />

Is pushing your car a sign of true love? Are you sufficiently devoted to your historic car not to mind being stranded at the roadside? Having to search<br />

for the nearest bus or train can be a turn-off for the most avid aficionado. A reliable supply of spare parts is one of the most important issues for lovers<br />

of historic vehicles.<br />

by Sandra Bieberstein<br />

Of course, it’s great when you can cruise<br />

along country lanes in your classic car<br />

enjoying the feeling of driving as it used<br />

to be. You don’t just need good maintenance<br />

to keep the wheels turning. The<br />

odd repair is also necessary. And that’s<br />

where spare parts come in handy.<br />

This is an important topic for drivers<br />

and for <strong>BMW</strong>. More than 60 percent of<br />

classic car owners service their own classic<br />

vehicles. They also do the occasional<br />

repair. This was revealed by the survey<br />

“Classics of the Future 2003” carried out<br />

by motor magazine Motor Klassik. That’s<br />

Page 12<br />

when the mechanically minded enthusiast<br />

needs spare parts. They’re certainly<br />

not easy to find. <strong>Car</strong> owners generally<br />

look to dealers or specialists for spare<br />

parts (80.9 percent) and recently the<br />

Internet has become an important source<br />

(42.4 percent).<br />

Order from ...<br />

Overall, more than 80 percent of owners<br />

of classic cars are satisfied with the supply<br />

of spare parts. Automobile manufacturers<br />

have also played a key role here. In<br />

order to keep the history of the company<br />

and its vehicles a<strong>live</strong> and make that history<br />

accessible to the community of <strong>BMW</strong><br />

enthusiasts, the <strong>BMW</strong> Group founded<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> in 1994. A<br />

specialist team is dedicated to parts supply<br />

and particularly to the manufacture of<br />

replica parts for historic <strong>BMW</strong> vehicles.<br />

Generally speaking, parts are supplied<br />

there for historic vehicles 15 years<br />

after the end of volume production in the<br />

case of automobiles and 20 years after<br />

production ceases in the case of<br />

motorcycles. It doesn’t matter whether<br />

you’re looking for a sealing ring, a wing,

door, windscreen wiper, gear lever, saddle cover, cable harness<br />

or speedo – you can get virtually anything. If an owner of a historic<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> vehicle needs a spare part, they should seek advice<br />

from their dealer in the first instance. Dealers have access to a<br />

large online parts catalogue managed by <strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong><br />

<strong>Tradition</strong>. The appropriate part can then be found quickly and<br />

ordered. The spare part arrives within the space of a few days<br />

and it can then be installed in the vehicle. You can then get back<br />

on the road.<br />

But what happens when the purchase order is sent off and<br />

there are no more parts in stock? That’s when the team at parts<br />

supply and replica manufacture come into their own – although<br />

they’ve often taken action much sooner. They sit down together<br />

with mechanics, experts from purchasing and materials management<br />

specialists, and come up with a solution to the problem.<br />

The search for information on spare parts<br />

The first step is to get all the necessary information about the<br />

production method in order to manufacture the missing part.<br />

The search includes drawings, any samples available and technical<br />

specifications. It’s essential to find out what material the<br />

relevant part was made of and the various processes that were<br />

carried out on it. One of the most important resources in this<br />

search is <strong>BMW</strong>’s Technical Archive. This includes drawings and<br />

documents with technical specifications.<br />

Once all the information has been collected, a supplier has<br />

to be found. Manufacturing a part like this on the basis of the<br />

documents is sometimes extremely straightforward, but it can<br />

be very tricky. An order for manufacturing a part presents a considerable<br />

challenge to the supplier because it is necessary to<br />

meet the quality requirements of <strong>BMW</strong> – and today some production<br />

methods are completely obsolete. But that’s not the<br />

end of the story. The supplier also has to be prepared to produce<br />

a relatively low batch volume and costs should not be<br />

excessive.<br />

Manufacture and pricing<br />

Unfortunately, the tools for manufacturing the original parts<br />

have often been scrapped long since and they then have to be<br />

remade by a toolmaker. If all the tools are available, an initial<br />

sample needs to be produced. This sample is tested and modified<br />

until it meets the quality standard of <strong>BMW</strong>. Only then is it<br />

possible to commence actual production. Here there is also an<br />

ongoing process of quality control and sampling.<br />

After all, any customer has the right to receive perfect<br />

goods in return for their money. Sufficient parts are then produced<br />

to ensure supply for the long term. This might involve<br />

continuous production of replica parts over a number of years or<br />

one-off production to<br />

create a “Stock for Eternity”.<br />

In order to estimate<br />

how many parts are necessary,<br />

research is carried<br />

out on the market<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> 02 Series: front trim<br />

grille is a typical spare part<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong>: Production of replica parts<br />

Procedure for manufacture of a replica part<br />

A complex and often tedious process takes place before a new “old” spare part<br />

becomes available. This is shown here with reference to manufacturing a replica<br />

front trim grille in the 02 Series.<br />

Inspecting and procuring technical<br />

documentation at <strong>BMW</strong>.<br />

Writing a milling program for tool<br />

production.<br />

Technical consultation with suppliers.<br />

Laser machining after the first<br />

pressing.<br />

The part is pressed out. The part is produced from a number<br />

of individual components.<br />

The part ist tested by the inspection<br />

machine.<br />

Fitting a sample in the workshop<br />

at <strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong>.<br />

Quality control and acceptance<br />

of the initial sample by <strong>BMW</strong>.<br />

Front trim grilles are taken into<br />

stock at <strong>BMW</strong> spare parts store.<br />

<strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> <strong>live</strong> / Issue 02.2003 Page 13

and any possible competitors in an<br />

attempt to estimate the demand for this<br />

particular spare part so that replica parts<br />

“never” have to be manufactured again.<br />

The comparatively high production<br />

costs – costs for tools, manufacture, storage<br />

and sales define the pricing structure<br />

– mean that price increases for replica<br />

parts often cannot be avoided. However,<br />

the aim is always to match the price of<br />

comparable or similar parts. <strong>BMW</strong><br />

regards this as part of the service provided<br />

by an automobile manufacturer who is<br />

particularly concerned to meet the needs<br />

of aficionados driving classic vehicles.<br />

Once the replica of the spare part<br />

has been manufactured in the quantity<br />

ordered or calculated, further quality<br />

control measures are undertaken and<br />

the entire production batch is then taken<br />

into stock.<br />

There is an average lead time of six<br />

months from ordering the part, through<br />

replica production to placing the part in<br />

stock. However, sometimes it takes even<br />

longer to manufacture a replica part. This<br />

is generally due to the difficulty of finding<br />

suppliers who have the appropriate production<br />

methods available, meet the<br />

Supply cycle<br />

Parts requirement<br />

current up to 15 years<br />

Volume<br />

production<br />

Page 14<br />

Parts supply by<br />

<strong>BMW</strong><br />

up to 50 years<br />

Individual<br />

restoration<br />

Specialist production<br />

of replica parts<br />

quality requirements and are also prepared<br />

to produce a low batch volume of<br />

this nature. Materials and machining<br />

spare parts may also be problematic.<br />

Processing methods are often no longer<br />

used – in the worst case scenario, the<br />

material no longer exists. The only option<br />

then is to look for production methods<br />

that meet the same or higher standards.<br />

When the production process presents<br />

particular technical difficulties, it is generally<br />

necessary to produce a large number<br />

of initial samples before quality meets<br />

the high requirements necessary.<br />

Spare parts catalogue and<br />

replica parts list<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> publishes all the<br />

available parts in an online parts catalogue<br />

which is updated on an ongoing<br />

basis. The same applies to replica parts.<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> dealers are now able to order the<br />

replica part again. A monthly list of replica<br />

parts is also published. Moreover, automobile<br />

and club magazines receive information<br />

about “old” parts that have been<br />

manufactured again.<br />

More than 20,000 parts for classic<br />

vehicles are kept in stock and almost<br />

half of them have been<br />

manufactured by <strong>BMW</strong><br />

Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> in<br />

this way. In the year 2002<br />

alone, around 1,000 different<br />

replica parts were produced.<br />

However, problems<br />

don’t always keep to reg-<br />

Age<br />

of car<br />

ular opening times.<br />

Classic-car aficionados<br />

can undertake research<br />

themselves using the<br />

parts catalogue on CD-<br />

ROM. Enthusiasts will find<br />

all the available parts in<br />

the historic parts cata-<br />

logue. There is an exploded view of<br />

each part, parts are coded by type and<br />

given their designated part number.<br />

<strong>Car</strong> owners have also been able to<br />

access the parts catalogue and the<br />

monthly lists of replica-part production<br />

online since May 2003. Anyone interested<br />

can go to the internet page<br />

www.bmw-mobiletradition.com and click<br />

on the field “Parts supply”, select<br />

“Historic parts catalogue” and then register.<br />

Registration is simple and free of<br />

charge. Access to the catalogue is granted<br />

within two working days.<br />

Anyone interested in additional information<br />

on this subject is recommended<br />

to go to the home page of <strong>BMW</strong> Group<br />

<strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong>. There is a link under<br />

“<strong>Tradition</strong> Aktuell/News” to a talkshow<br />

held in German on the stand of <strong>BMW</strong><br />

Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> at the Techno<br />

Classica 2003 exhibition. Representatives<br />

of supply companies discuss the<br />

situation and the problems associated<br />

with supplying parts for classic cars.<br />

Supplied with all the data<br />

Parts supply organized like this enables<br />

the owners of historic <strong>BMW</strong> vehicles to<br />

maintain their “darlings” to an extremely<br />

high standard. They can enjoy the feeling<br />

of driving as it used to be to the full,<br />

with a minimum of unscheduled interruptions.<br />

The historic parts catalogue can be<br />

ordered as a CD-ROM from any <strong>BMW</strong><br />

dealer. The “Parts Catalogue for Historic<br />

Automobiles and Motorcycles 2003” has<br />

order number 70 00 0 301 255. This includes<br />

all the data for classic <strong>BMW</strong> automobiles<br />

and motorcycles. There is also a<br />

printed parts catalogue with part number<br />

01 20 5 590 032 for classic <strong>BMW</strong> motorcycles.<br />

The “Parts Catalogue for Historic<br />

Motorcycles 2003” on CD-ROM can be ordered<br />

citing part number 72 00 0 154 486.

<strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> <strong>live</strong>: Mr Breuckmann, as President of the <strong>BMW</strong> Z1<br />

<strong>Club</strong> with more than 250 members you are not just the owner of this<br />

classic car from <strong>BMW</strong>. In collaboration with Maik Hirschfeld, engineering<br />

director of the association, you also represent the interests of the<br />

members when it comes to technical issues relating to this vehicle.<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> has been responsible for supplying parts<br />

for the Z1 Roadster since 1997. How important is the procurement of<br />

spare parts?<br />

Horst W. Breukmann: Procurement of spare parts is a top priority for<br />

the very existence of a classic car and essential for keeping it on the<br />

road. A large number of classic car enthusiasts spend a great deal of<br />

time and effort in exploring all the possibilities for acquiring a key<br />

spare part that they urgently require in order to breathe new life into<br />

their stranded classic car.<br />

The slogan of our brand The Ultimate Driving Machine highlights<br />

the fact that a <strong>BMW</strong> Z1 is not an exhibition object, but the mobile<br />

expression of a development epoch at <strong>BMW</strong>. Guaranteed production<br />

of replica parts and supply of spare parts is absolutely essential if<br />

we are to continue to enjoy this Ultimate Driving Machine in the<br />

years and decades to come. It’s vital for us to address spare parts<br />

supply for the future at a very early stage.<br />

How do you rate the service provided by <strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong><br />

<strong>Tradition</strong> in maintaining parts supply for the Z1 over the long term?<br />

We are in the fortunate situation that long before the deadline for<br />

guaranteeing supply of spare parts expired, <strong>BMW</strong> AG decided in<br />

conjunction with our club to keep the classic Z1 Roadster on our<br />

roads for as long as possible.<br />

Undoubtedly it’s an innovation that already six years after production<br />

of our Z1 came to an end, spare parts supply was started up in the<br />

classic section of <strong>BMW</strong>. This underlines very clearly that the car has<br />

succeeded in becoming established in the family of <strong>BMW</strong> classic<br />

cars – no mean feat given the relative youth of this car.<br />

This service provided by <strong>BMW</strong> AG reassures all drivers of the Z1 that<br />

they don’t have to lay in a stock of parts as a reserve, which is often<br />

not terribly effective in the case of many parts. As long as there is<br />

commitment to supplying spare parts that are in demand over the<br />

long term – sometimes possibly within a reasonable timeframe – we<br />

rate the service provided by <strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> very highly<br />

<strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong>: Production of replica parts<br />

“We rate the service provided by <strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> very highly.”<br />

<strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> <strong>live</strong> spoke to Horst W. Breukmann, President of<br />

the <strong>BMW</strong> Z1 <strong>Club</strong>, about the nuts and bolts relating to the key issue<br />

of parts supply for collectors of historic vehicles.<br />

and trust that the current system will remain in place for many<br />

years to come.<br />

To what extent do you use other options for obtaining spare parts,<br />

for example as used parts?<br />

The number of models manufactured amounts to just 8,000 and<br />

the fact that the Z1 has been moving towards classic status for a<br />

number of years now means that this car is generally extremely well<br />

looked after. The option of cannibalizing a Z1 hardly ever arises,<br />

not even with a firm specializing in culling parts from old cars. That<br />

means that this source of parts is simply not available.<br />

If the part you happen to be looking for is one of the standard<br />

E30 parts built into the Z1 (for example in the engine), it’s<br />

definitely possible to make use of this option. But even if you’re<br />

dealing with what are supposed to be standard parts, you<br />

sometimes still need the instinct of a mechanic in order to<br />

make minor adjustments.<br />

Otherwise, there are virtually no other options for getting hold<br />

of the majority of parts specific to the Z1, such as the window-lift<br />

mechanism, headlamps, the outer panels with their thermo<br />

plastic elements, the seat elements and similar items through<br />

any sources other than those referred to.<br />

Incidentally, one objective of our club is to maintain the Z1 Roadster<br />

as closely as possible to its original status on the road to becoming a<br />

classic. This inevitably means that original manufacturer’s parts<br />

should always be used.<br />

How satisfied are you with the service you receive when ordering<br />

spare parts? Are there any suggestions for improvement that you<br />

would like to make?<br />

Basically, we’re very satisfied with this service. But as in all other<br />

areas of life, there’s always room for improvement. We’re in close<br />

contact with those responsible at <strong>BMW</strong> Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong><br />

in order to solve any problems that crop up. We are extremely<br />

gratified that they are always ready to discuss any concerns and<br />

problems we may have.<br />

More attention needs to be paid to “quality assurance”. This is<br />

particularly important when suppliers of replica parts change, and<br />

it is crucial especially in the case of thermoplastic panelling or<br />

other sensitive elements. The importance of this aspect should<br />

not be underestimated.<br />

At this point, I should like to mention that the possibility of accessing<br />

the current status of replica parts production on the home page of <strong>BMW</strong><br />

Group <strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> is a very welcome and indeed exemplary service<br />

for the Z1 and for other cars.<br />

We should like to thank you for your interview and wish you and all<br />

the other members of the <strong>BMW</strong> Z1 <strong>Club</strong> a good journey in the future.<br />

<strong>Mobile</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> <strong>live</strong> / Issue 02.2003 Page 15

Paul Rosche: engine guru and downto-earth<br />

Bavarian<br />

20 years ago <strong>BMW</strong> won the Formula One World Championship with Brabham and Nelson Piquet and a <strong>BMW</strong> turbocharged engine. The engine was<br />

designed by Paul Rosche. He is one of the icons of motorsport, even though he has never projected a big profile as a person.<br />

When Bernie Ecclestone was asked<br />

about Paul Rosche, he once said: “Paul<br />

Rosche? He’s a great bloke. Like me, he’s<br />

one of the old guard. And I mean that<br />

both in terms of his character and his abilities<br />

as a designer. There’s a simple formula<br />

for both: you can rely on him.” The<br />

world of motorsport calls him “Camshaft<br />

Paul” and the stories about him are<br />

Paul Rosche of <strong>BMW</strong> Motorsport talking to Niki Lauda<br />

(McLaren).<br />

Quotes<br />

“Not only did Rosche have brilliant ideas, you could also have<br />

a glass of beer with him.”<br />

Niki Lauda<br />

“His great achievement is his vision, which he brings to fruition<br />