The 2024 Campaign Calendar is the twentieth edition!

With the December holiday season comes my annual Mount Hood National Park Campaign calendar, but this year is a bit of a milestone: the 2024 calendar is the 20th edition since I began putting these together back in 2003! Much has changed over those years, so this article includes both a retrospective from the early calendars and highlights from the 2024 edition, so I hope you’ll indulge me!

The new calendars for 2024 are print-on-demand and available now from Zazzle. You can find them here:

See the 2024 Mount Hood National Park Campaign Calendar on Zazzle

Zazzle does excellent work and these can be shipped direct to anywhere. As always, all proceeds go to Trailkeepers of Oregon (TKO) for their crucial work in volunteer trail stewardship and advocacy.

Looking back to the very beginning…

It was back in 2003 when I kicked off the “idea campaign” for a Mount Hood National Park that encompasses Mount Hood and the Gorge. It’s an idea that has made it as far as legislation in Congress on several occasions as early as the 1890s, but never made it as far as the president’s desk to become law – usually due to moneyed interests in exploiting the mountain. Thus, the purpose of the “idea campaign” is to simply keep the national park idea alive.

Shooting the Salmon River with my first digital camera in 2003 (Greg Lief)

I’ve been asked many times “do you really think Mount Hood will become a national park?” I do, of course. Eventually. Most of our national parks had a long and bumpy road to finally being established, often starting as a national monument or recreation area – but always because they had exceptional natural and cultural features unmatched elsewhere. That’s why I believe that Mount Hood will eventually join the ranks of Crater Lake, Mount Rainier and the Olympics and receive the level of commitment to both conservation and recreation that only the National Park Service can offer. In the meantime, this blog serves as place to celebrate those natural and cultural features that make Mount Hood and the Gorge unparalleled places worth protecting, while spotlighting threats to the mountain.

With this goal, the first calendar (below) was an outgrowth of the idea campaign as a visual way to celebrate the many places and landscapes that combine to make WyEast Country so exceptional. Back in 2004, there were also new technologies that helped make a custom calendar possible: I had recently purchased my first digital camera and CafePress had emerged as a quality on-demand printing service as part of the dotcom revolution.

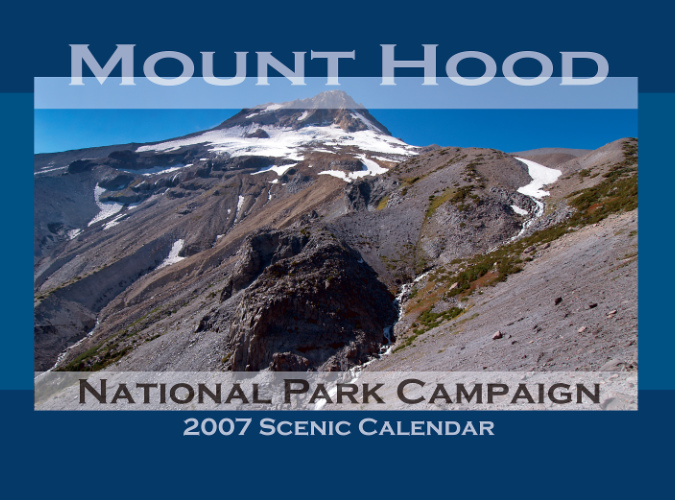

The first cover… back in 2004

The first calendar was modest – printed at 8.5×11 inches with color reproduction that was decidedly “approximate”, though still a big leap forward from color photocopies of the 1990s. The first edition featured a recurring, favorite spot of mine on the cover – Elk Cove on Mount Hood’s north side.

From this start, the calendar evolved over the next 20 years in technology, print quality and the landscapes I featured. This collage (below) of the 20 annual covers shows some of that evolution.

[click here for a large version]

Looking back, the two constants among cover subjects were waterfalls and the mountain, though the places and vantage points varied greatly. One of the best rewards in putting the calendars together has been the opportunity to explore different corners of the mountain and gorge, as I set a goal early on to feature new images taken during the previous year in each calendar. While there are a few spots I go back to nearly every year, I’ve also been able to feature new places and perspectives not seen elsewhere.

Looking across those old cover images, I’m also able to see how the cover design evolved. The first two calendars used a script font that looks ridiculous to me now, and by 2006 I had moved on to the “national park” fonts I use today – notably, Copperplate — along with the color scheme I had used on the (then) brand new Mount Hood National Park Campaign website. The graphic below the main image was from bumper stickers I also had printed at CafePress at the time.

Getting there… improved fonts in 2006

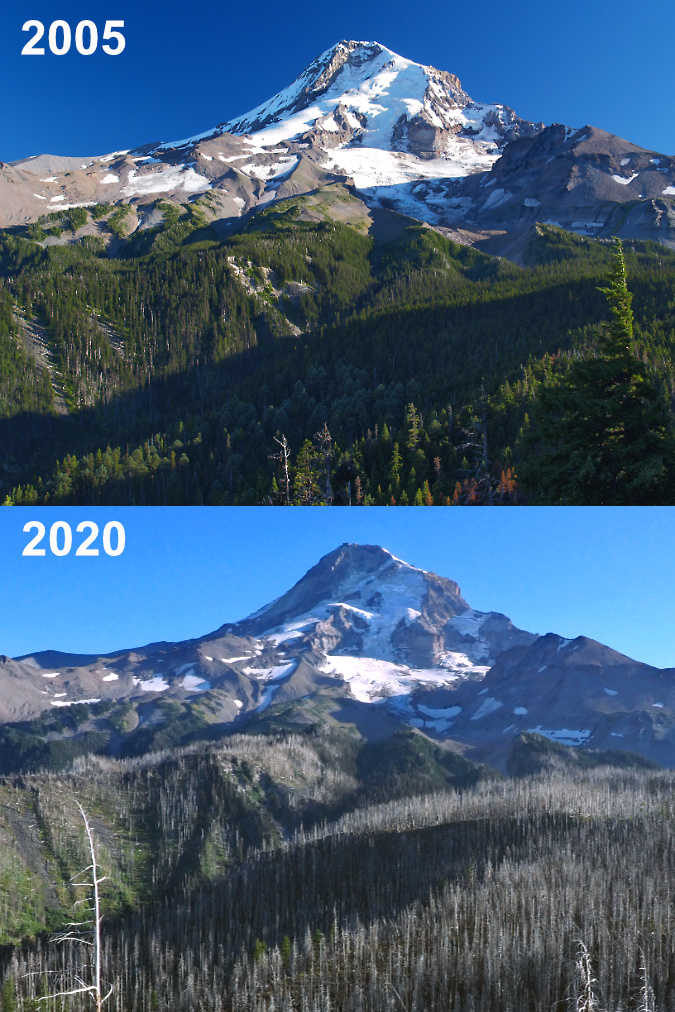

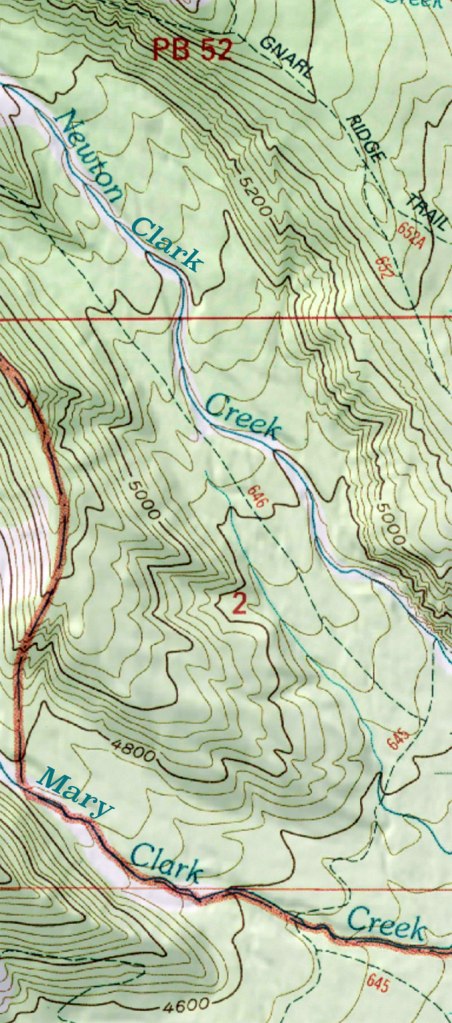

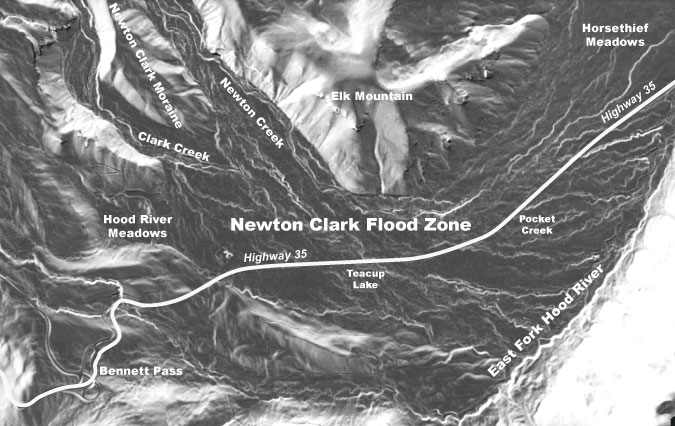

The cover of the 2006 calendar is the first in a series of reminder among the covers that there are no constants in WyEast Country. Everything changes, and lately, change seems to be accelerating, as the cover image of Mount Hood from the Elk Cove trail underscores. Just two years after I took this photo, the Gnarl Fire had roared across the east flank of the mountain, nearly engulfing Cloud Cap Inn. Then, three years after the Gnarl Fire, the Dollar Lake Fire had burned much of the forest on the north slope of the mountain shown in this image.

The 2011 Dollar Lake Fire started just below the rocky viewpoint where this cover photo was taken. Today, the sea of green Noble Fir and Mountain Hemlock that once covered the slopes has been replaced by a ghost forest of silver tree skeletons, with a new forest just getting underway in their. The following photo comparison from this viewpoint (below) shows the dramatic changes to the north side in stark contrast.

The Dollar Lake Fire burned thousands of acres of subalpine forest on Mount Hood’s north slope in 2011

The Dollar Lake Fire brought an unexpected opportunity to witness and document the forest recovery, and without the assistance of man, as most of the fire was within the Mount Hood Wilderness. As such, the Forest Service has adopted a hands-off policy and is deferring to the natural forest recovery process. I’ve since posted several articles tracking the recovery:

“After the Dollar Lake Fire” (June 2012)

“Dollar Lake Fire: Five Years After” (October 2016)

“10 Years After the Dollar Lake Fire” (November 2022)

The 2007 calendar marked a technology change when CafePress began offering a much larger format, measuring 11×17”. This required a different photo aspect, but also gave sweeping vistas the space they need to be truly appreciated. Such was the case with the first calendar cover in this larger format in 2007, when the sprawling view of Mount Hood’s east face (below) from Gnarl Ridge was the cover image. This edition also featured what has become the basic design for the cover, along with a blue color scheme that I’ve alternated with the original green theme over the years.

Going ultra-wide with a new format in 2007

In 2008, I started this blog as an alternative to making constant updates to the campaign website. This opened still more opportunities to explore and capture WyEast country in words and imagery, with deeper dives and more details in the long form that I prefer. As the blog shifted my focus toward emerging risks to Mount Hood and the Gorge, so my photography shifted, and the calendar began to include more remote and obscure places on the mountain.

There’s a story behind the nearly identical cover scenes of Upper McCord Falls (below) that appeared on both the 2011 and 2013 calendars. In 2012 I lost all of my original digital files from the 2011 calendar in a computer upgrade, and by 2013 I’d clearly forgotten what the earlier cover images was. Apparently, I liked that view of Upper McCord Falls enough to put it back on the cover — though I had also upgraded my camera between these covers, so at least the 2013 version was an improvement on the earlier take – to my eye, at least! (for this article, I recreated the 2011 cover from a printed copy of the calendar I saved).

Seeing double-double!

As with so many places in the Gorge that I had taken for granted in my life, it never occurred to me that the forests surrounding Elowah Falls and Upper McCord Falls would soon be completely burned, leaving a landscape will take generations to return to the lush, mature forests that I grew up with. As it turned out, Upper McCord Falls was the first trail I visited within the “restricted area” following the September 2017 Eagle Creek Fire. It was just five months after the fire when I headed up there in February 2018 with a Trailkeepers of Oregon (TKO) crew to survey the trail damage.

The devastation was much more extensive than I expected on what would be the first of many trips into the restricted area after the fire. I had hiked through the recent burns on Mount Hood in previous years, and was braced for seeing ancient trees reduced to burned snags, but what makes the aftermath of fire in the Gorge so unique is the terrain. The forest was playing a greater role in holding the steep slopes of the Gorge together than I think anyone realized, and just five months after the fire the scale of erosion and ground movement was alarming.

Locating surviving trail tread after the fire at McCord Creek in early 2018

The scene at Upper McCord Falls was startling, as well. The burn was severe around the falls, killing the entire forest. The layers of green moss that survived the burn on the cliffs and boulders nearest the falls seemed like they had been hand-tinted onto the brown landscape, like an old postcard.

Upper McCord Falls in February 2018 (Randi Mendoza, Oregon Parks & Recreation)

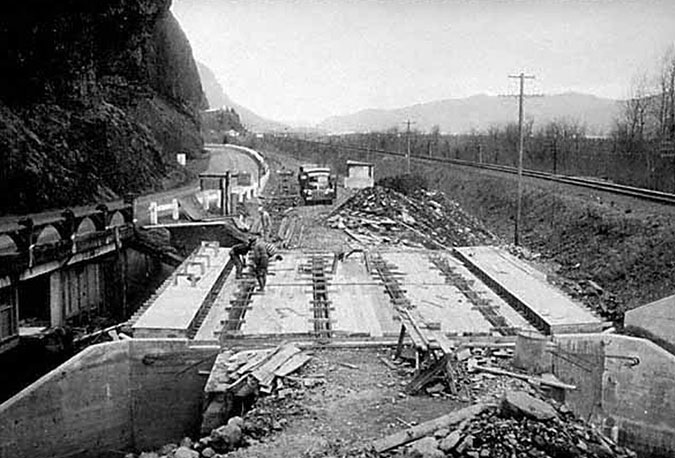

The trail seemed a total loss in several areas on that trip where sliding mud and rock had completely covered the tight series of switchbacks originally carved into the slope by the Civilian Conservation Corps back in the 1930s. In the years that followed the fire, TKO volunteers have removed tons of debris from the trail and reconstructed damaged stone walls built by the CCC, restoring the tread to nearly its original design today.

Upper McCord Falls a few months after the fire

On the way out from that first visit after the fire, the clouds broke at the west end of the Gorge just as darkness was falling, creating the weird illusion that the charred forest silhouetted against dark the clouds and flaming sunset was still burning. As with all who love the Gorge, it was the beginning of a journey for me in accepting the reality of the fire – including the senseless act that started the blaze, as well as the inevitability of this fire being long overdue – and finally, a deeper appreciation for the resilience of our forests in which fire an essential destructive force.

Burned forests at McCord Creek on my first trip after the fire appeared to be on fire, once again, as a brilliant sunset lit up at the west end of he Gorge

Revisiting the slopes leading to Upper McCord Falls last spring, the resurgence of the understory and beginnings of a new forest was inspiring after five summers of forest recovery. While I won’t live long enough to see big trees replace those that were killed in the fire, the surviving trees are bouncing back strongly, and watching the renewal of the Gorge forests is as inspiring in its own way as the big trees we lost.

A stand of Douglas fir that survived the fire is surrounded by a thriving understory along the McCord Creek trail in Spring 2023

Meanwhile, Upper McCord Falls looks quite different five years later, as well (below). The understory has made a vigorous comeback, but more surprising is the east (left) segment of this twin falls, which appears to be plugged with debris released into McCord Creek from the fire – at least for now. Prior to the burn, the twin tier would have been flowing when I took this photo last spring, just as it was in the calendar covers in 2011 and 2013.

Upper McCord Falls six years after the fire in Spring 2023

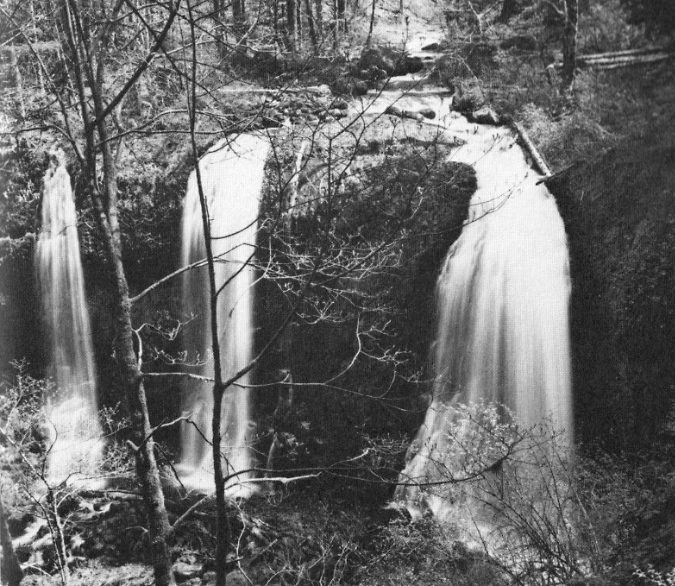

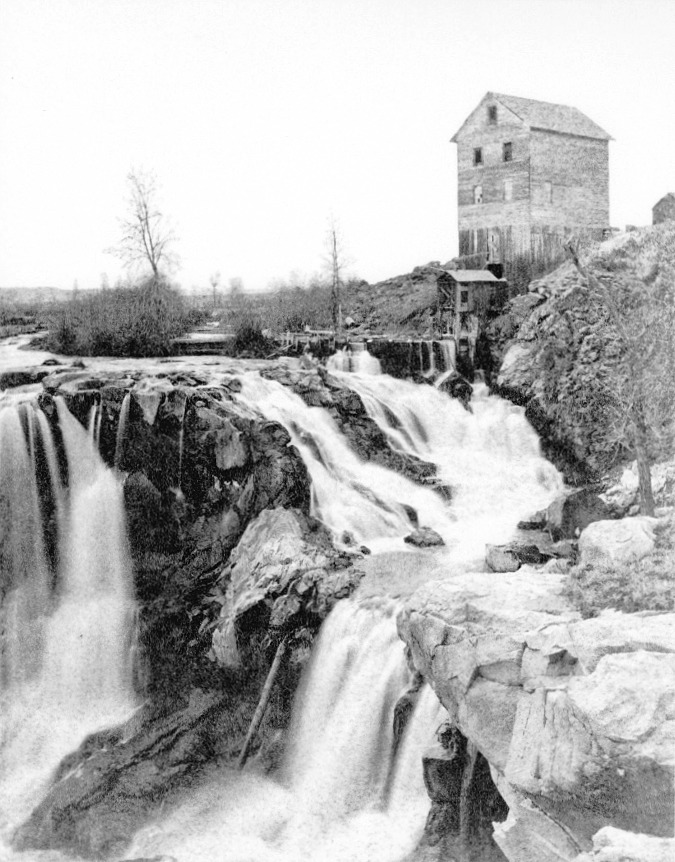

Upper McCord Falls has historically had as many as three segments cascading from the basalt ledge that forms the cascade (a third tier once flowed to the left of east tier as recently as the 1970s, as shown below), so in time, there’s no reason to assume the second (or even third) tiers will re-emerge. The defining factor is simply the amount of rock and log debris piled up on top of the basalt ledge.

Since the 1970s, the debris had been further stabilized by a colony of Red Alder that was the main force holding the pile of boulders and debris together, eventually blocking the third tier of the falls completely. Today, those trees have been killed, and with the volatile flooding on Gorge streams since the fire, there’s good reason to expect McCord Creek to re-arrange the shape of Upper McCord Falls by removing some or all of the debris plugging parts of the waterfall.

Upper McCord was a triple falls in the 1970s! (Don Lowe)

Where the tree canopy along the McCord Creek trail system were completely burned (below), the forest recovery is now in full swing, choking the route in many spots with Thimbleberry, Vine Maple, Douglas Maple and many other understory plants whose roots survived the burn, allowing them to bounce back quickly.

Forest understory surging back after six years at McCord Creek

Bigleaf Maple are bouncing back in this way, too, pointing to a future deciduous forest canopy as the first phase of recovery in many of the burned areas. Along the lower sections of the McCord Creek trail, ten-foot shoots have exploded from the roots of Bigleaf maple trees whose killed tops still stand as bleached snags (below). Many of these recovering maples will become multi-stemmed trees, a familiar sight in Oregon’s forest and one answer as to why mature Bigleaf Maple so often have multiple trunks.

Bigleaf Maples regrowing from the base of burned trees whose roots survived the fire

The drama at McCord Creek continued a few short years after the fire when the west cliff wall of the Elowah Falls amphitheater collapsed in the winter of 2021. There’s no science (yet) to make the connection, but the Gorge has seen a series of cliff failures since the 2017 Eagle Creek Fire. Could these events be linked to the loss of vegetation or corresponding runoff on Gorge slopes? Perhaps, but as I described in the previous article on the 1973 Tanner Creek landslide, there are unique forces at work in the Gorge that date back to the last ice age, so events like these are the norm, not the exception.

Elowah Falls cliff collapse in the spring of 2021 (Drew Stock, Trailkeepers of Oregon)

TKO volunteers discovered the Elowah Falls cliff collapse in 2021 and captured the dramatic photos shown here. In the immediate aftermath of the collapse, McCord Creek disappeared into the loose basalt cobbles that had filled the creek channel and buried the Trail 400 footbridge to its railings. That condition was temporary, however, as by last spring McCord Creek had already carried away much of the small debris and excavated the footbridge. The images below show the erosive power of the stream over a period of just two years.

Debris burying McCord Creek and its footbridge immediately after the collapse (Drew Stock, Trailkeepers of Oregon)

Elowah Falls footbridge excavated (and railings removed!) by McCord Creek after just two years

Like most cliff collapses in the Gorge, the jumbled debris fan at Elowah Falls is a mix of truck-sized boulders that managed to hold together amid a sea of smaller boulders and fractured basalt cobbles where parts of the once-solid rock face had simply crumbled during the event.

Large blocks of basalt mixed with smaller cobbles in the debris pile at the base of the collapsed cliff

Today, a massive scar is still obvious on the cliff wall where the basalt gave way (below). In time, however, the evidence from event will be hidden under a fresh carpet of moss and Licorice Fern, once again giving that deceptive illusion of stability that has never really existed in the Gorge.

Looking up the debris fan at the massive scar left behind by the cliff collapse at Elowah Falls in Spring 2023

While the cliff collapse at Elowah Falls was massive in scale, it spared the spectacular trail to Upper McCord Falls where it is carved into the basalt walls 400 feet above the creek. In fact, hikers passing along this vertigo-inducing stretch of trail might not even notice that a large section of the wall directly below them had collapsed into the creek, as the impact is mostly hidden from this airy view (below).

Elowah Falls seems unchanged from above along the Upper McCord Trail

If the cliff collapse Elowah Falls was impressive to see, the earlier collapse at Punch Bowl Falls on Eagle Creek was downright shocking. After Multnomah Falls, and Crown Point, the view into the mossy cavern that holds Punch Bowl Falls might be the most iconic in the Gorge. The idyllic scene drew photographers from around the world before the fire, and even gave its name to the category of “punchbowl” waterfalls.

Punch Bowl Falls as it once appeared in 2012

I posted an extensive piece on this event when it showed up unexpectedly on a series of aerial surveys the State of Oregon had conducted to track landslides after the Eagle Creek Fire. The Punch Bowl collapse occurred just months after the fire, sometime in early 2018. The “restricted area” was still in effect at the time, so the first few people to see the aftermath in person were trail volunteers working to put the Eagle Creek trail back together. Today, you can see the re-arranged landscape by taking the Lower Punch Bowl spur trail down to the falls.

Aftermath of the 2018 cliff collapse at Punch Bowl Falls

Getting that classic shot of Punch Bowl Falls during spring runoff usually entailed wading knee-deep into Eagle Creek to get a look into the hidden cavern that holds the falls. The cliff collapse has since changed things a bit. For now, there are a pair of good-sized boulders that landed in the entrance to the cavern, blocking the traditional view.

In time, Eagle Creek will dismantle much of the debris from the collapse, and even these boulders will eventually break apart or be pushed downstream by the enormous force of the stream during winter floods. This will be aided by the many fallen logs that have dropped into the stream since the fire, and now act as erosive battering rams and levers as they move downstream.

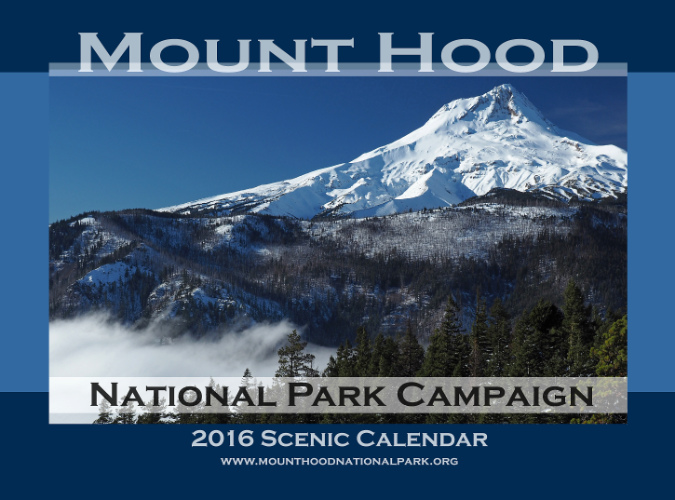

The ”modern” calendar design emerges in 2016

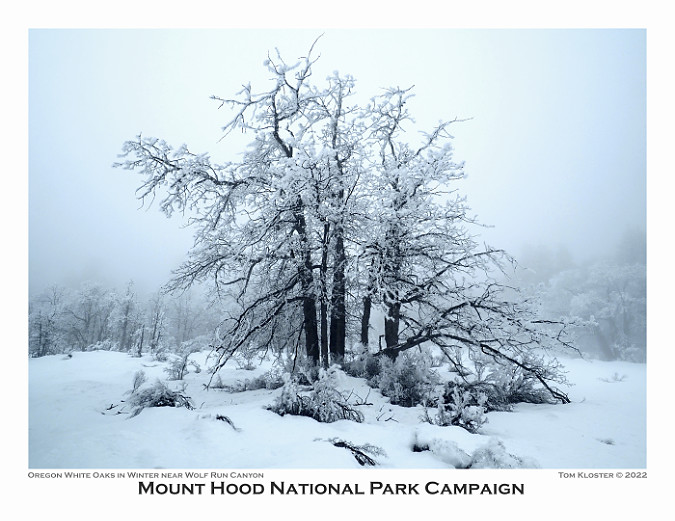

The final design and format emerged in 2016 with a switch in vendors

Year twelve in the calendar series brought a major shift and format and improved quality when I moved printing from CafePress to Zazzle. The image reproduction at Zazzle is excellent and the overall printing process much better, resolving some quality concerns that drove me to make the move. Zazzle also brought the added opportunity to have a printed back cover on the calendar, kicking off the grid of nine botanical photos that I continue to include each year. Like the scenic views in each calendar, the botanical images are captured over the course of the prior year on my forays into WyEast Country.

New with the 2016 calendar? A printed back cover!

One last profile of note from past calendars is the 2019 edition, where lovely Whale Creek in the Clackamas River watershed is featured. This idyllic scene is – or was – typical of the beautiful rainforests there. Despite a long and frustrating history of aggressive logging over more than a past century, some of the finest ancient forests in the region survived here. Sadly, the Riverside Fire – yet another human-caused event – started just upstream from this spot along the Clackamas, and eventually burned 120,000 acres of forest, as well as numerous structures.

This scene from Whale Creek taken before the 2020 Riverside Fire was featured on the 2019 calendar

I’ve posted many articles on the necessity and benefits of wildfire in our forests, but the Riverside Fire underscores a few caveats to the science. As I described in this 2021 article, we are burning our forests faster than is sustainable. This stems from multiple factors adding up to a perfect storm: a century of fire suppression coupled with heavy logging has left us with thousands of old clearcuts packed with thickets of overplanted, fire-prone young trees and decades of fuel buildup. Add climate change, with our summers getting drier and hotter, and our forests have become a tinder box in most years, not just the occasional hot summer.

The same section of Whale Creek after the fire in 2020 (USFS)

Given this confluence of stresses on our forests, we’re doing an especially poor job preventing human-caused fires – they account for 70 percent of wildfires in Oregon! As I point out in the linked article, we’ll need to set some unwelcome limits on human behavior if we hope to slow down the burning to sustainable levels. So far, the Forest Service is moving very slowly in limited access during extreme fire danger, though successful liability lawsuits against power companies whose live lines triggered some of the 2020 fires may change that thinking.

TKO crews clearing big logs on the Clackamas River Trail after the Riverside Fire

Some good news from the Clackamas? TKO crews have already been working on reopening trails damaged in the fire. Like the Gorge, the Clackamas River canyon is steep country, so keeping trails open as the forest recovers will be a long-term endeavor.

That’s a look back at 20 years of campaign calendars, and now…

…looking ahead to 2024!

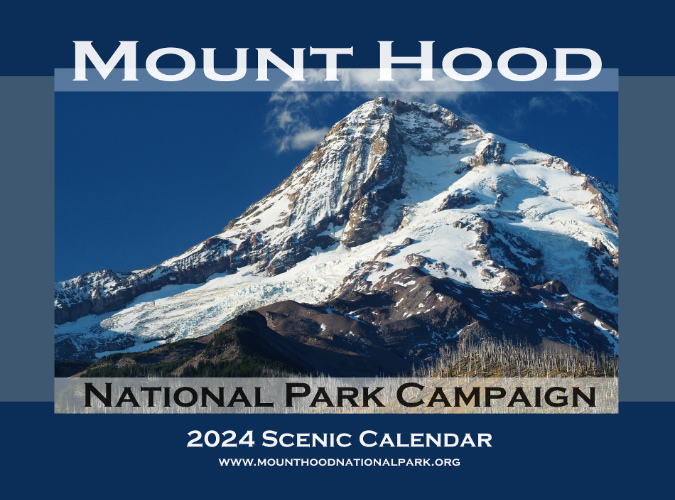

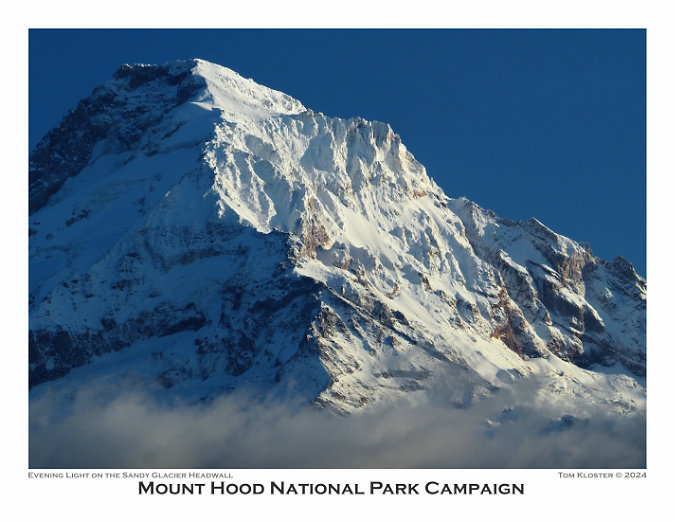

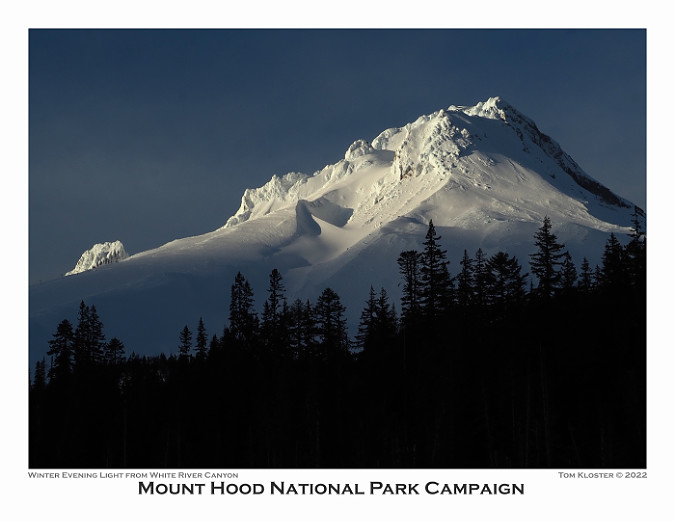

The view from Inspiration Point is the cover image for 2024

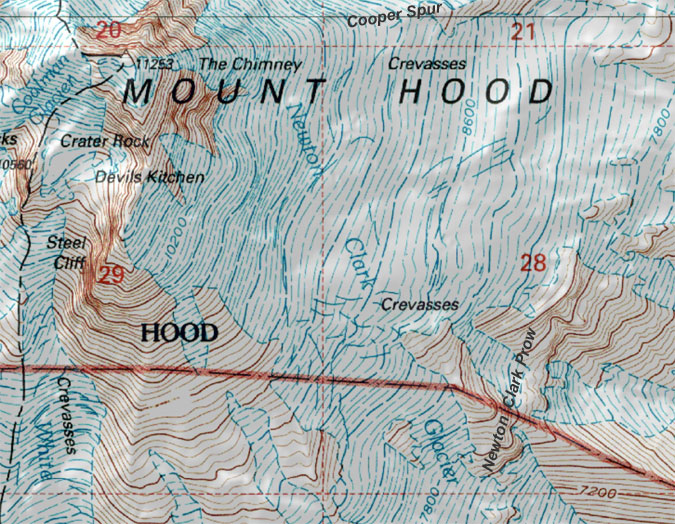

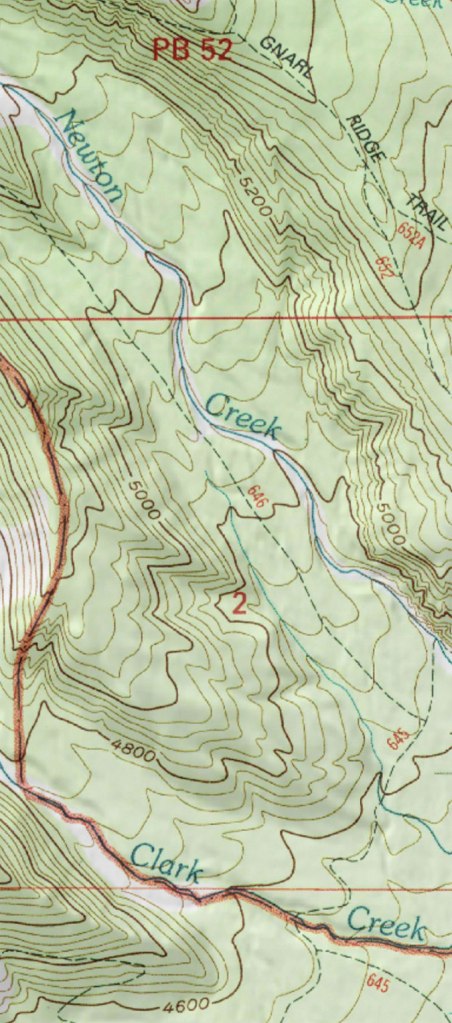

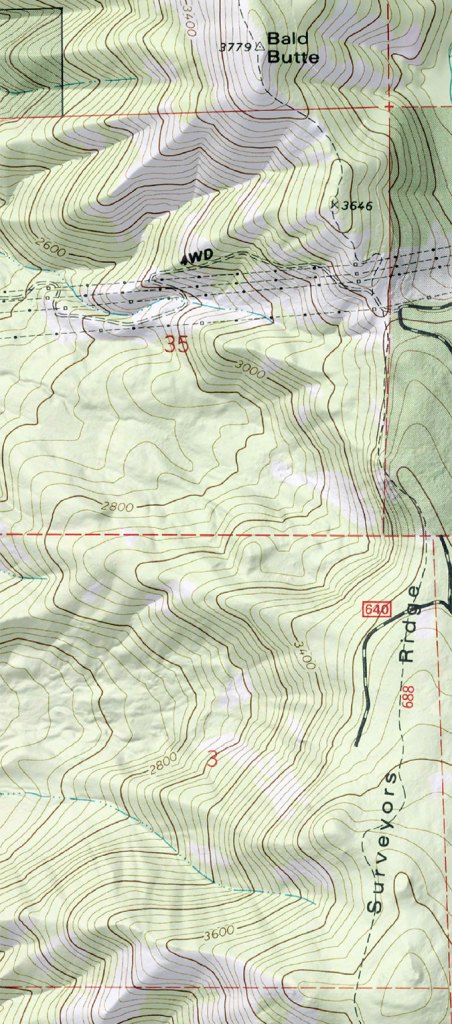

For the 2024 calendar cover, I selected an image of Mount Hood’s fearsome north face (above), as viewed from a tiny, unofficial trail that I maintain at Inspiration Point (located at the 3-mile mark on bumpy Cloud Cap Road). How long have I been stopping here? I looked back at my photo archive, and the earliest I could find was a slide from the summer of 1984 – which means I’ll celebrate my 40th summer visiting this lovely spot when I stop at Inspiration Point next year!

Clouds capping the mountain on the road to Cloud Cap in this 1980s view from Inspiration Point

On the back cover of the new calendar, yet another collection of nine wildflowers that I photographed over the past year is featured – including a couple that were new to me.

Back cover of the 2024 calendar

Putting it all together, here’s a jumbo collage of the 12 monthly images in the 2024 calendar, plus the covers and a snapshot of the page layout:

[click here for a large version]

For the January image in the new calendar (below), I selected a view of Mount Hood’s northwest side, with Cathedral Ridge and the Sandy Glacier Headwall covered in an early dusting of autumn snow. On this day last October, the mountain was emerging from the clouds after being socked in most of the day.

Northwest face of Mount Hood with early autumn snow

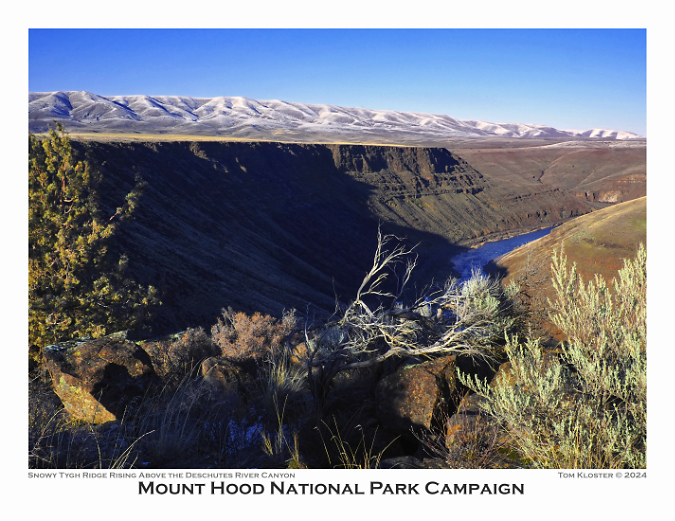

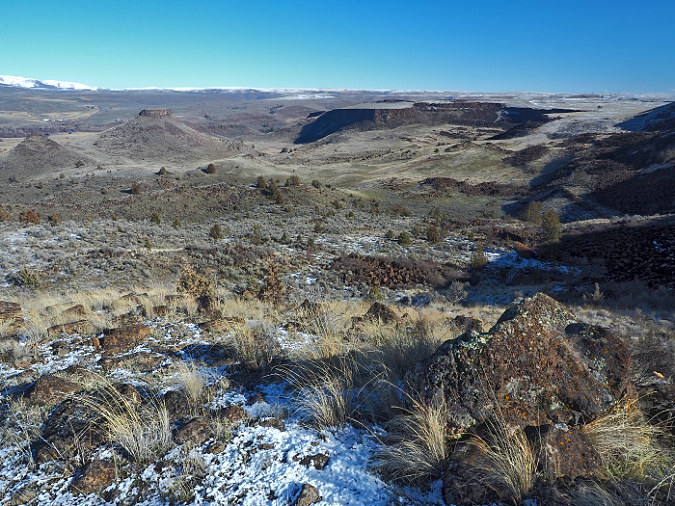

For the February image I thought I’d mix things up a bit with this view of the lower Deschutes River canyon at Oak Springs (below), a corner of WyEast Country that not many find their way to. On this day last winter, a dusting of snow had fallen on Tygh Ridge, the long fault scarp that rises in the distance – another lesser visited spot on this lonely, dry side of the mountain.

Lower Deschutes River and Tygh Ridge from above Oak Springs

For March, a more familiar scene (below) along a quiet section of the lower Salmon River features a group of Lady Ferns. The Old Salmon River Trail follows this stretch of river through some of the best rainforest and oldest trees within easy reach of Portland.

Lower Salmon River in Spring

I chose another stream scene for April, though this one is less familiar to most. This is Viento Creek (below), in the east Gorge, just a few miles west of Hood River at Viento State Park.

Viento Creek in the East Gorge

There’s a backstory associated with this photo, as I’ve been working with TKO for the past few years to create a new family-friendly trail from the Viento Campground to a magnificent viewpoint on the Viento Bluffs. The new trail will someday pass the stream scene shown above, enroute to expansive views of the Columbia River – but with a short route that it will be welcoming to casual hikers and young kids. Watch this space for more news on this project!

TKO and State Parks crew surveying a new trail at Viento Bluff earlier this year

The picturesque view from Viento Bluff will someday become a family trail destination

The May calendar image features another stretch of the Salmon River (below). This pretty cascade has become a popular spot for photographers in recent years. I included it in this year’s calendar partly for symbolic purposes, as this scene appeared in the very first calendar in 2004. This is also where Greg Lief’s image at the top of this article of me shooting photos was captured in 2003 – hard to believe that was 20 years ago!

Springtime on the Salmon River

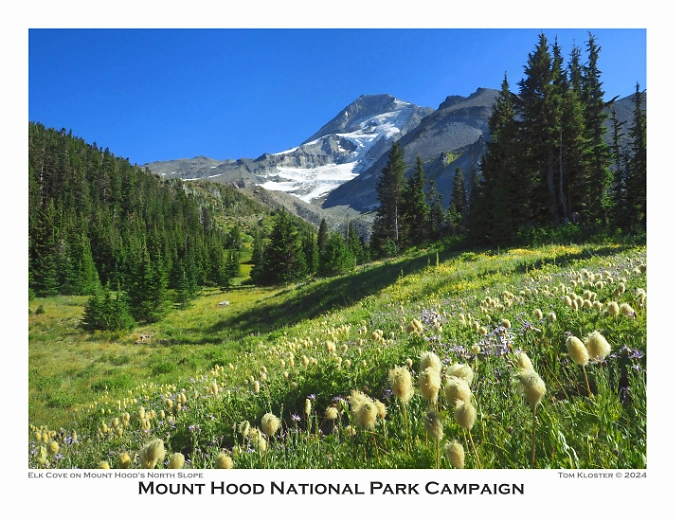

June brings another symbolic favorite, as Elk Cove appeared on the cover of the first calendar, and in several subsequent editions over the years – and almost always from this very spot (below) along the Timberline Trail. As much as the mountain has changed in recent years, this view remains a bit of a constant – always lovely, but especially the Western Pasqueflower are putting on their “Muppets of the Mountains” show.

Summer wildflowers putting on their annual show at Elk Cove

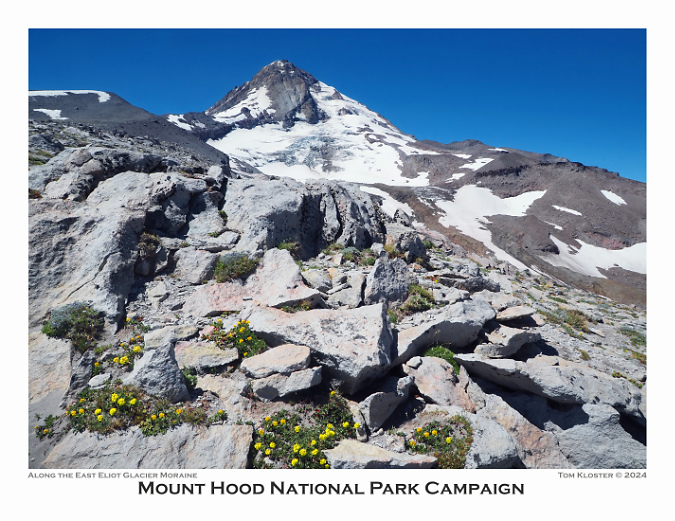

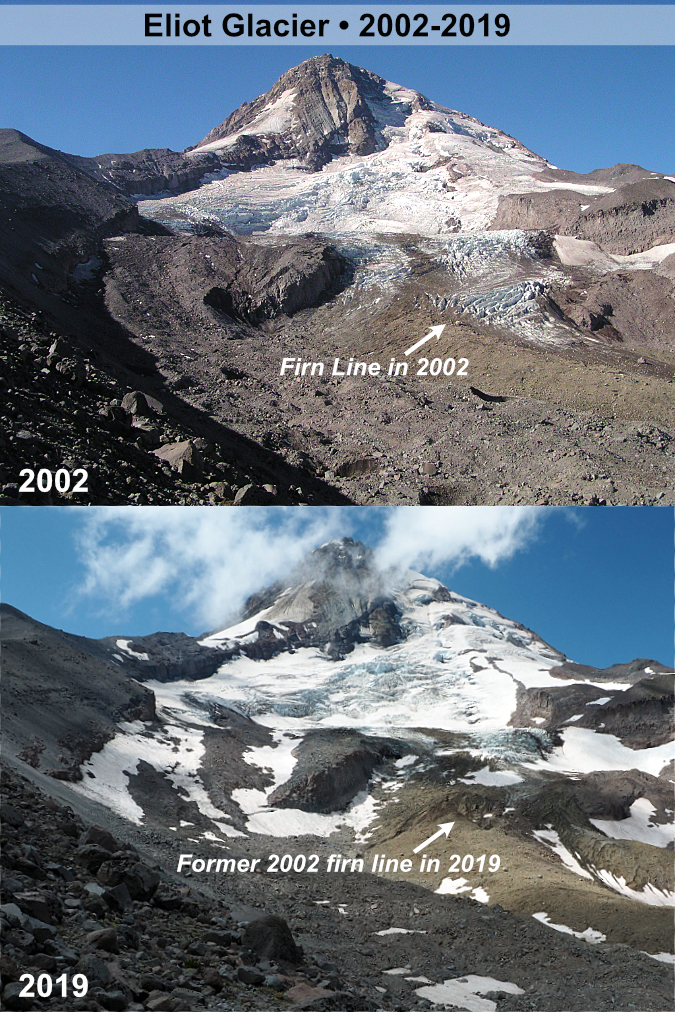

For July I selected another repeat spot, one of my favorite viewpoints of Mount Hood and the Eliot Glacier from the shoulder of Cooper Spur (below). I posted a look-back article on this area earlier this year to kick off a series of then-and-now photo retrospectives.

Mount Hood and the Eliot Glacier from the Cooper Spur Trail

For the August image, I selected another scene from a blog article, in this case a view of the recovering Muddy Fork valley where a landslide swept through two decades ago. This event and several now-and-then photo comparisons are over here.

Muddy Fork of the Sandy River

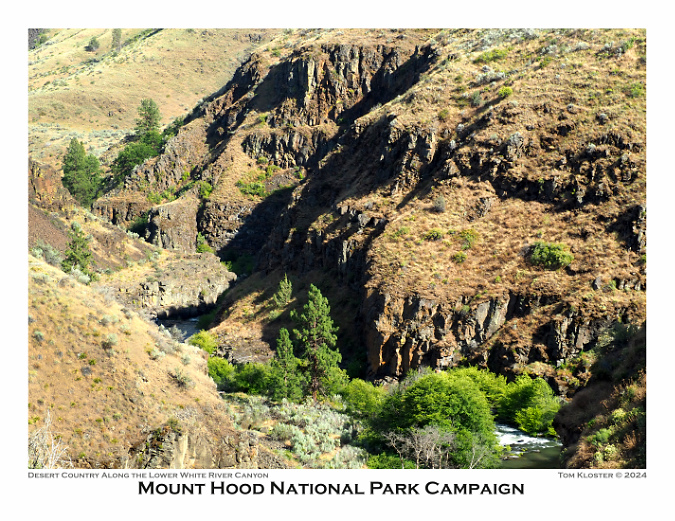

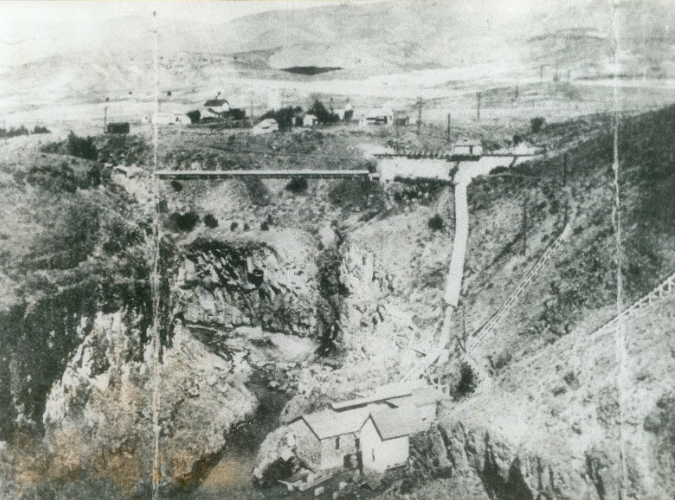

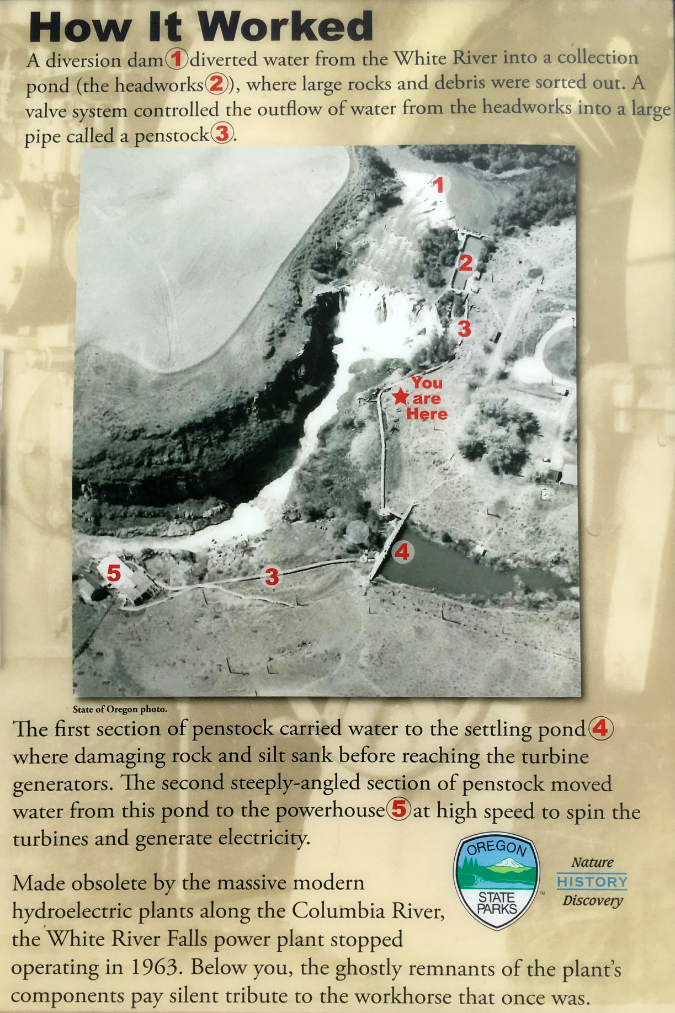

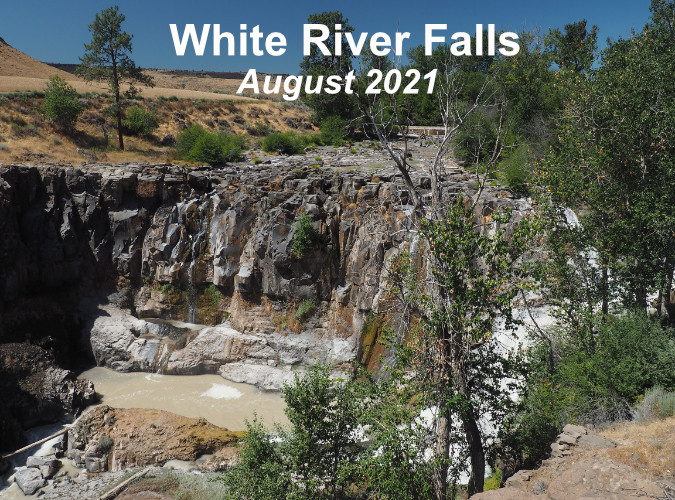

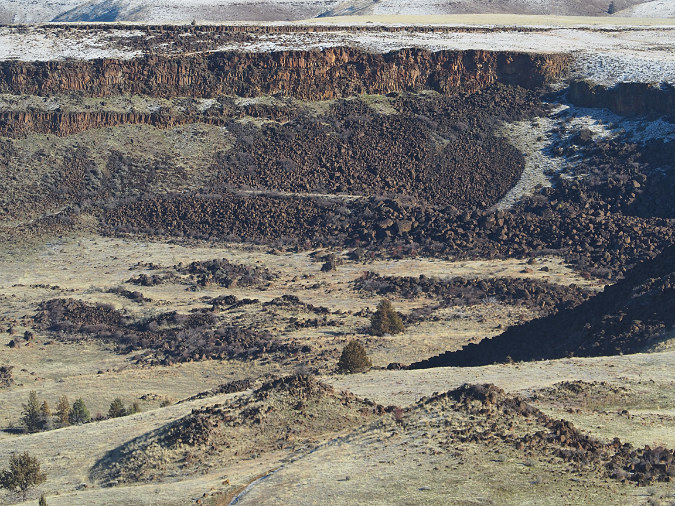

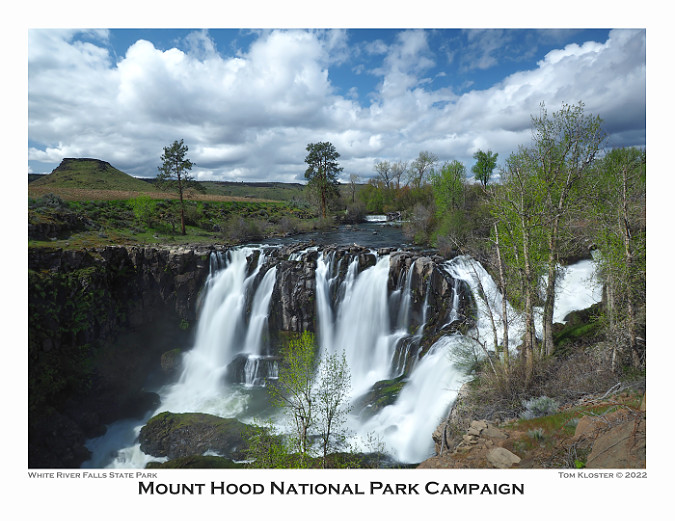

For September, I chose something a bit different, with a cliff-top view into the lower White River Canyon (below) at White River Falls State Park. So many things make Mount Hood unique (and worthy of national park protection!), but the compact collection of wildly different climate zones might be at the top of the list. There aren’t many places in the world where a 2-hour drive from the middle of a major metropolitan area takes you from rainforest to desert, with glacier-covered volcano rising above you the entire time!

Lower White River Canyon in desert country

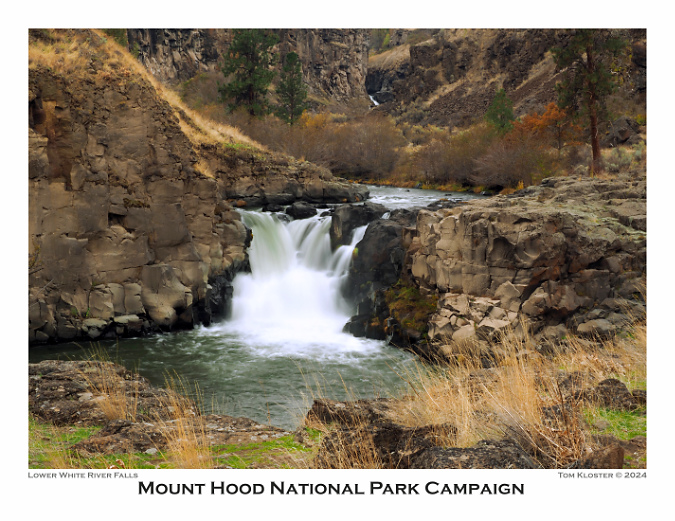

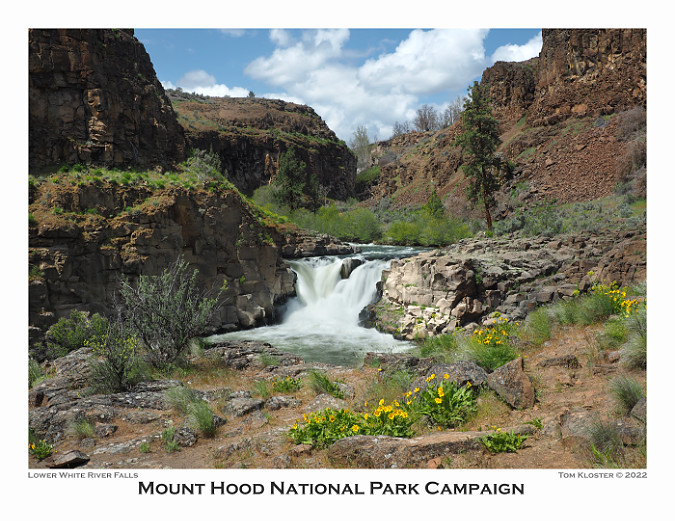

The October image stays with the desert theme, and features Lower White River Falls. In spring, this canyon lights up with desert wildflowers that I’ve included in previous calendar editions, but the tawny yellows, gold and reds of autumn create their own beauty in this rugged landscape.

Lower White River Falls in Autumn

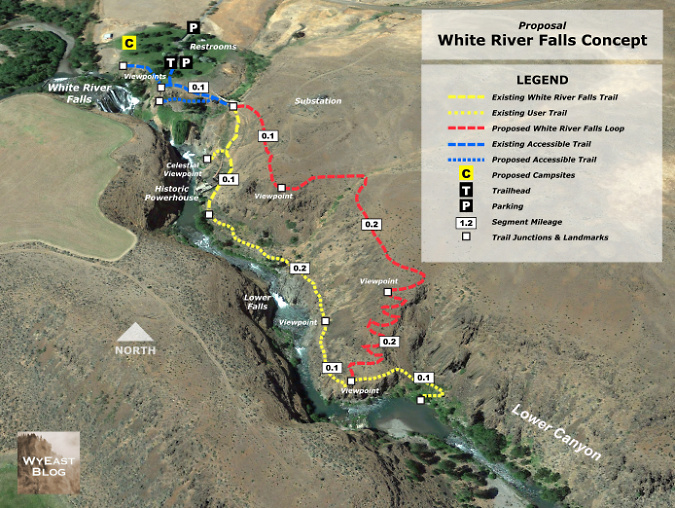

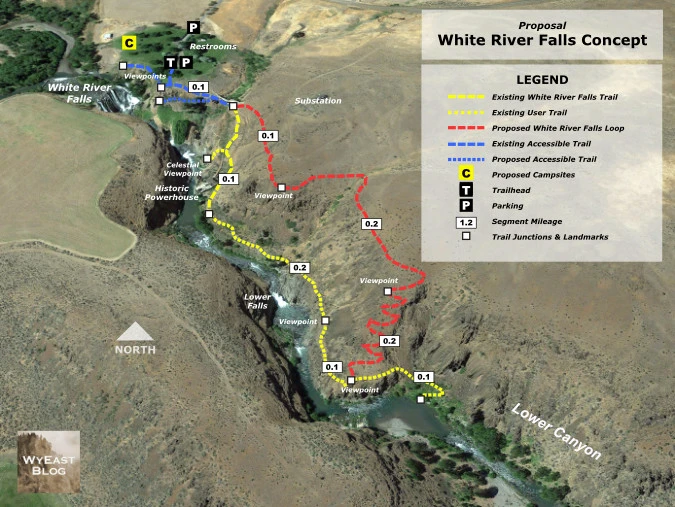

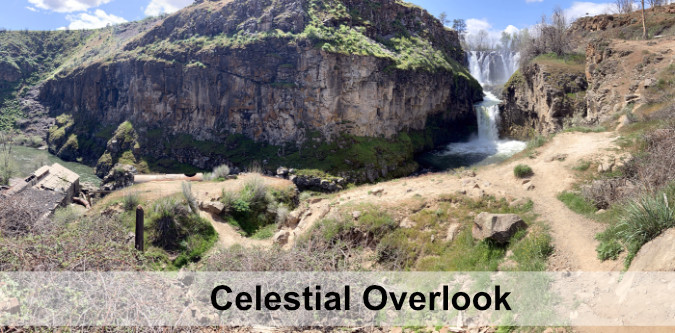

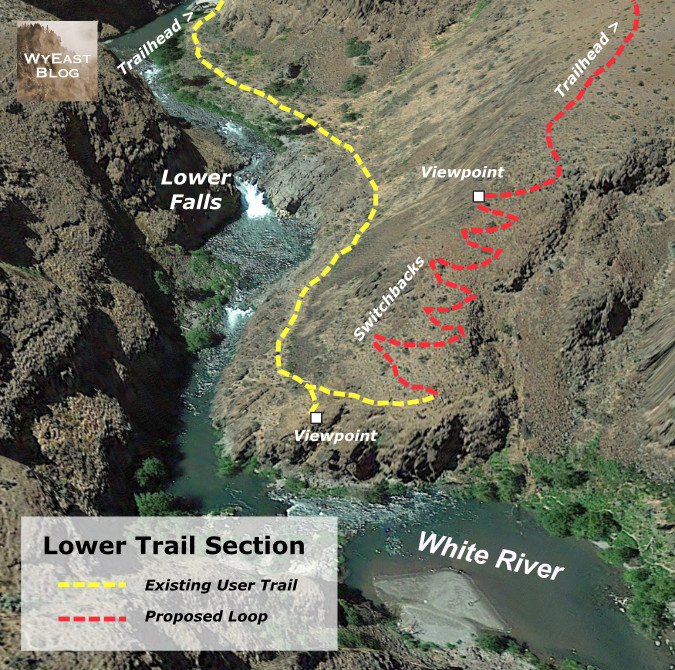

White River Falls State Park remains a diamond in the rough, with much potential for both improved recreation and conservation of the natural and cultural features in the park. The area is becoming more popular, and that has translated into some visible impacts – and therefore several proposals to respond to this increased demand are featured in this article from earlier this year.

Loop Trail concept for White River Falls State Park

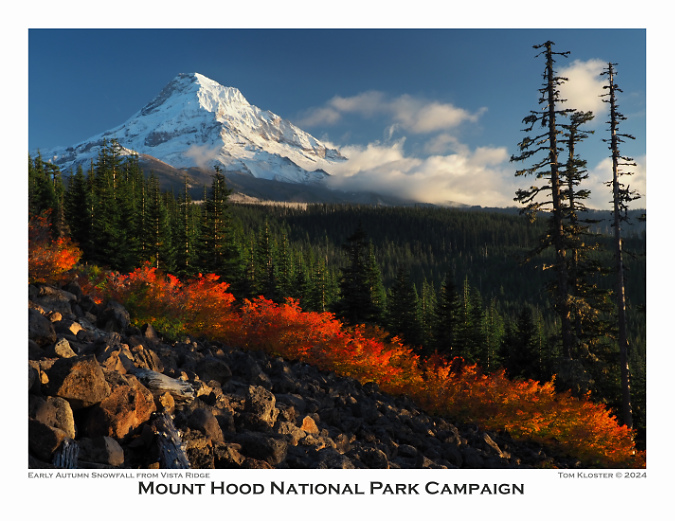

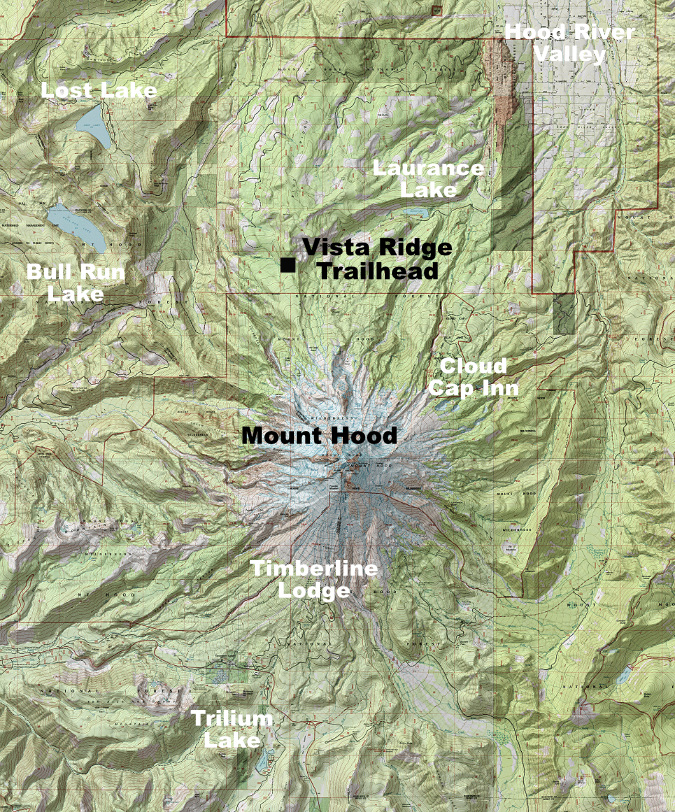

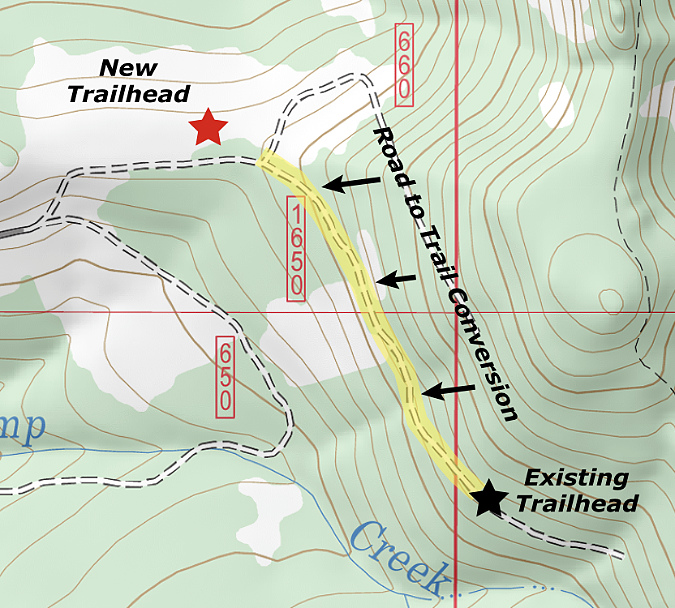

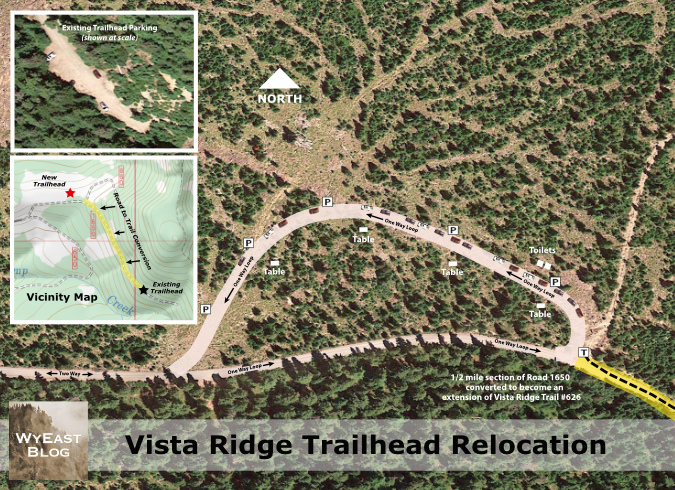

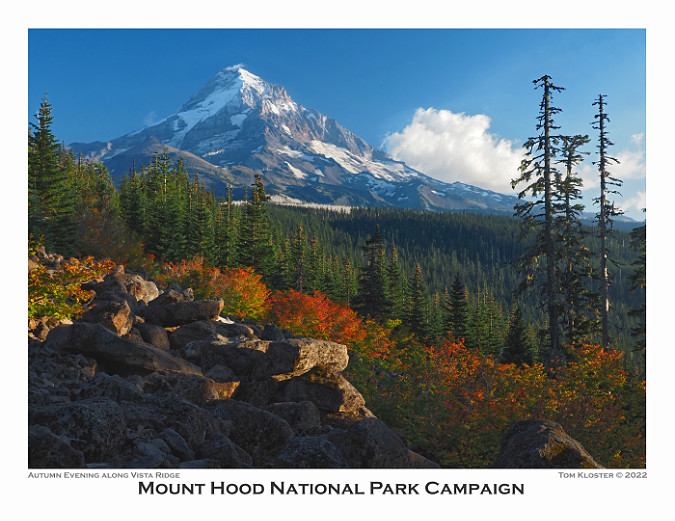

For November, fall colors along Vista Ridge and fresh snow on the mountain are featured (below). This scene is surprisingly easy to get to – it’s along the access road to the Vista Ridge Trailhead, another increasingly popular spot on the mountain. This article from last summer includes some proposals for managing the pressures the newfound popularity is bringing to Vista Ridge.

Brilliant fall colors on Vista Ridge

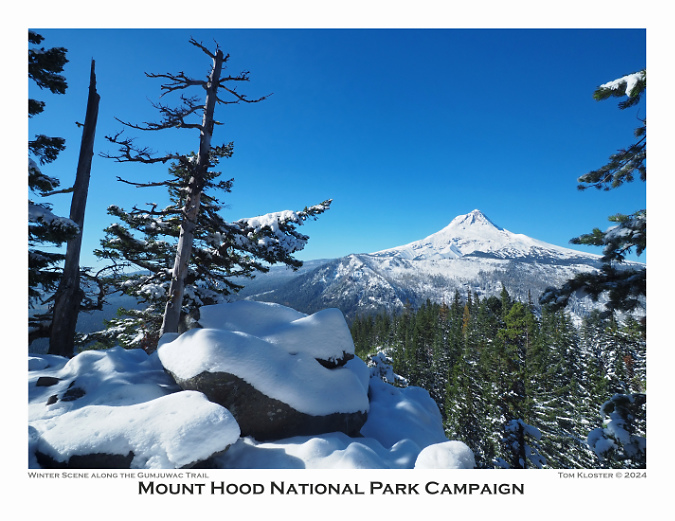

Finally, a view of the mountain after the first big snowfall of the season (below) from the lightly traveled Gumjuwac Trail, gateway to the Badger Creek Wilderness. My favorite viewpoint hikes are to “pocket views” – those spots where a steep talus slope or rocky outcrop provides an unexpected view – and this rocky crest just below Gumjuwac Saddle is among the best, and was featured on the front of the 2016 calendar, as well.

Pocket viewpoint along the Gumjuwac Trail in winter

On the way up to the Gumjuwac viewpoint, I followed the chunky footprints of a Black bear for much of the route. Hiking in snow is a useful reminder that wildlife are always out there, even if we don’t have snow on the ground to record their travels. This is their home, after all, we are the visitors.

Bear tracks along the Gumjuwac Trail

Bear tracks in fresh snow on the Gumjuwac Trail

So, that’s it for my annual calendar review! If you made it this far and would like order one, they are available here – and all proceeds go to Trailkeepers of Oregon (TKO):

2024 Mount Hood National Park Calendar

As always, thanks for visiting the blog. Looking ahead to next year, I already have several articles underway, with the usual collection of deep dives, new proposals and reflections on the past. I hope you’ll continue to stop by!

The author at Owl Point in 2008 (Andy Prahl)

Best to you in the coming year – see you on the trail in 2024!

_______________

Tom Kloster | December 2023