If you haven’t yet read part 1 of Lancia – A History, you’ve missed a lot: the beginning of the famous brand in November, 1906; their first car, the Tipo 51 (Alfa); their journey through WWII and the flourishing ’60s.

We touched on some of the stunning coachbuilt examples from the likes of Zagato, Pininfarina and Bertone, and some of the production vehicles that provided such wonderful underpinnings. What is clear is that, from the beginning, Lancia were never one to hold back, and were never afraid to push boundaries.

Which is why what happened in 1969 took Lancia down a path from which they’d never return. But boy is it some journey.

A Change is as Good as a…

The year is 1969. The Flaminia is coming to the end of its life, the Flavia is in its swansong before changing to the name “2000” and the Fulvia is… well, still doing its thing.

In the premium segments that Lancia were competing in, its reputation was strong: the lance and flag logo stood for quality, well-engineered vehicles that consistently performed at the highest level, as showcased by their racing performances. Despite the loss of Vincenzo all the way back in 1937, his approach was well and truly ingrained into Lancia’s whole approach to designing and making cars: which came at a cost.

As the ‘60s progressed, premium manufacturers, particularly Mercedes Benz and BMW, were developing premium, high quality, saloons (sedans) with a high level of repeatability and quality. And thanks, especially, to their domestic market, they were shifting a lot of vehicles. Competition was now rife in the segment, and for a company like Lancia who didn’t have the process discipline to compete, it came as a shock.

There was no doubting the quality of what they were producing, but the cars were simply costing too much. The Italian government at the time stepped in and “enabled” a takeover by Fiat, in the belief that Fiat’s approach towards “economies of scale” could be taught to Lancia and they could return to profitability. Similar thinking was, as we know, taken with the likes of Rover and Saab, and we know how they ended…

Birth of the Beta

Three years into Fiat ownership, in 1972, the Lancia Beta was born. It was the first vehicle designed and released under Fiat ownership, and the first car since the Dilambda in 1928 to use the Greek alphabet as inspiration for its name, the word Beta used to symbolise a new beginning. It was designed, in stark comparison to previous Lancias, with a real focus on large volumes, so Fiat parts were sourced wherever possible, including the engine, whilst the gearbox used had been heavily developed by Citroen (a partner of Fiat) for a future launch of their own.

Despite a typically profitable vehicle production volume being around 100,000 p/annum, Fiat planned for early volumes of 40,000, perhaps as a worst case scenario. And they did recognise the importance of derivatives as a way of improving volumes, something Lancia had always done, but the body types they offered were confusing, to say the least.

The Beta Berlina fastback saloon was the first bodystyle to carry the new (yet old) Lancia Beta name, and all versions came with DOHC (Dual Overhead Camshaft) transversely mounted engines, rack and pinion steering and fully independent, front and rear, MacPherson strut suspension that used transverse links which pivoted on a centrally mounted cross member bolted to the underside of the floorpan. And to finish, an anti-roll bar was fitted to the floorpan ahead of the rear struts, with both ends of the bar bolting to the rear struts on each side. It was a completely unique setup, was never patented by Lancia and would go on to be used not only by future Lancias but many other OEMs during the ‘80s and ‘90s. So same old Lancia then!

RIP – Rust-Induced Proliferation

Shortly after the Berlina launch, a short wheelbase 2+2, 2-door Coupe followed that, even now, is quite handsome, and was followed not long afterwards by the Spyder, or Zagato in the US. This version had the curious combination of a targa-esque roof panel, rollover bar and folding canvas rear roof, and was once again designed by Pininfarina, but built by Zagato. It’s an odd mix of technology but, again, somewhat charming.

In 1974, Lancia took the covers off the Lancia Beta Montecarlo, or Scorpion in the US market, a rear-wheel drive, mid-engined two-seater sports car that had been designed by Pininfarina to replace the Fiat 124 as the Fiat X1/9; but Fiat chose the cheaper Bertone version and Lancia used it as a premium alternative to Fiat’s two-seater. It suffered a few issues during it’s lifetime, including poor ergonomics and a brake issue that took two years to solve, and lasted until ‘81, selling 7,798 in total.

And a year after launching the Montecarlo, the Beta HPE was introduced, a three-door sporting estate/ shooting-brake that added to the growing lineup of Beta curiosities. It had the Coupes front end and doors, but the Berlina’s floorpan and a unique rear, lasting nine years until production finally ended in 1984.

The Trevi arrived as the last in the lineup in 1980, and whilst from a Marketing standpoint it wasn’t a Beta, everything underneath the exterior panels pretty much was. It didn’t go well, and was criticised widely for what were seen as feeble attempts to rescue the brands image with gimmicky changes and rushed decisions. All because a crisis had hit Lancia during the early years of Beta production that they would never quite recover from. Rust.

The reasons may never come to light, and whilst it’s odd that rust problems dominated the Beta like no other Lancia before, or since, it also came at a time when many other manufacturers were also struggling with rust-proofing metal components and body structures.

During the 1970s, most automakers were experiencing growing pains, as they moved from medium volume vehicle lines to high volumes, which required a different approach to the entire design, development and manufacturing process. And rust-proofing was one of the low hanging fruits that were easily identifiable to customers and critics alike. So why did Lancia struggle more than anyone else?

Perhaps it was the Fiat Group’s panicked response, or Lancia’s particularly observant and discerning customer base, or perhaps Lancia were seen as outsiders in a market segment dominated by now familiar brands like Mercedes Benz, BMW & Rover, but one thing is certain; it damaged the brand irrevocably. Despite subsequent releases of other legendary models during the Beta’s lifetime, and considerable racing success on international rally circuits, the lance & flag badge had been permanently tainted.

Thin End of the Wedge

During the Lancia Beta’s entire 12-year lifetime, it sold just over 360,000 cars, so around 30,000 per year. Early sales of the Beta were very positive, the line-up having been both welcomed and positively reviewed by critics, but a combination of afore-mentioned problems and an over-extended lifecycle hit the Beta line-up hard. Things are sounding desperate, aren’t they?

Well, thankfully, despite all of this chaos, there was a shining light for the Turin brand, which followed only 12 months after the Beta launch. A tiny little thing called the Lancia Stratos.

The Stratos story actually begins in 1970, at the Turin Auto Show. For decades, Lancia had an unbreakable relationship with Pininfarina, since Vincenzo himself had helped to fund his friend Batista’s new coachbuilding venture, whilst Zagato had worked on several different projects for the Piemontese company. Bertone, who were busy working on projects for other companies including Lamborghini and Fiat, wanted a piece of the Lancia pie.

The opportunity presented itself in 1969, when Lancia began to consider a replacement for the ageing Fulvia. Nuccio himself decided to design an eye-catching model, not only to replace the Fulvia on the road, but in rally circuits as well. He used the running gear from a friend’s Fulvia Coupé and built his working model around it. It was called the Stratos Zero.

And with a final stroke of genius, he drove the concept to the Lancia factory gates, before passing underneath the security barrier to great applause from the workers. Mission Accomplished.

That was all the persuasion Lancia needed and, shortly after the Stratos Zero debuted in Turin, Bertone tasked Marcello Gandini with redesigning the concept for the road, fresh from his work on the Lamborghini Miura and Countach. Some CV, huh?!

The Icon

A year later, in 1971, Turin welcomed the Lancia Stratos HF prototype in fluorescent red trim and a Dino Ferrari V6 engine under the hood, despite Enzo Ferrari’s initial reluctance. In fact, despite the Stratos having been designed from scratch with the assumption of the Ferrari V6, Enzo had refused to provide engines for a project he saw as a competitor to the Dino; until Dino production ended, when 500 engines suddenly arrived at Lancia.

It was the first vehicle to be designed, from scratch, with rallying at its very core; and it showed. Not only is the thing fist-bitingly cool, it’s also ridiculously compact and therefore incredibly agile, whilst the front wraparound screen gives excellent visibility and the tiny front-end gives the driver immense confidence going into any corner.

The road-going version was named the Lancia Stratos HF Stradale, but every variant made (between 492 & 500 depending on who you speak to) had the Dino V6, albeit tuned differently, and each vehicle came in under 1000kg depending upon spec.

The car entered Group 4 rallying in final, homologated, guise in 1974 and immediately won the championship title, dominating the series. It followed it up with title wins in ‘75 and ‘76 and would likely have had further success had it been supported by Fiat, who instead favoured their own 131 Abarths. But it didn’t matter. It’s popularity was indisputable, the name Stratos quickly escalated to iconic status and Lancia’s reputation in rallying was well and truly established. So when the Stratos ended production, and rallying, in 1978, many people were left wondering how Lancia would follow it up.

Gammas & Deltas

Before discussing the follow-up to the Stratos, we need to go back to 1977, when Lancia replaced the Flavia: with the Gamma. Just as the Beta model at the time, it was a fastback Berlina that kicked things off, with a saloon style trunk and unique flat-4 engines – against Fiat’s wishes – specifically to allow Pininfarina to design the Coupe’s hood and windshield rake as desired.

Like a naughty schoolchild, Lancia were at it again.

Although the Gamma was the flagship of the Lancia range, in that it was an executive saloon/sedan in the same bracket as the BMW 5-Series and Mercedes Benz W123, Lancia had never followed a classical line-up of models, despite Fiat’s will.

The Gamma Coupe is probably the only reason to even mention the Gamma here, such is the lack of enthusiasm for the product. In total, 15,272 of the Berlina-style fastback saloon were made, whilst the coupe sold just shy of 6,800. There’s a rugged charm to it, and as can be expected, but thanks to Lancia’s stubborn engine decision, it lacked the punch of many competitors. So let’s move on, shall we? To the Delta.

The Lancia Delta arrived in 1979 and is, to this day, Lancia’s most popular vehicle. Designed by Giorgetto Giugiaro, the legendary designer responsible for all manner of automotive gifts including the BMW M1, Maserati Ghibli and Lotus Esprit, it debuted as a five-door hatchback, was sold in Scandinavia under a licence with Saab and won the 1980 European Car of the Year.

Positioned below the Beta as an upmarket family hatchback, think Audi A3 or BMW 1 Series, the Delta launched at the Frankfurt Motorshow in October 1979 and, by the end of 1981 had sold more than 100,000 vehicles. And it’s easy to see why.

Despite using a suite of Fiat derived engines, Lancia soon got to work on them, adding a twin-choke carburettor, unique intake manifold, electronic ignition and a new exhaust system, giving a 10hp increase over the Fiat version. Under the metalwork lay fully independent suspension, rack and pinion steering, optional air conditioning, Saab-assisted split-folding rear seats, a height-adjustable steering wheel and Saab-designed ventilation.

Visually, aside from the obvious square proportions that were very much of the time, the body-coloured bumpers were made from a plastic sheet moulding compound (SMC) that, whilst ubiquitous in the industry now, was touted as a first back then, and the tailgate opening stretched all the way to the rear bumper, maximising usability.

1982 brought a slightly sportier variant, the GT 1600, wearing a small body-coloured rear spoiler that would soon become a popular visual feature. The Delta HF (High Fidelity) was launched in 1984, the year the 200,000th Delta was made. They were steadily building a reputation; and a good one.

But before we begin talking about the wonderful derivatives of the Delta that tied-in so intricately with Lancia’s racing heritage, we need to cover a few more points; including a rather wonderful, and often overlooked car. So let’s travel back in time a few years; to 1980.

Group B

If you like cars, and someone says to you “Group B”, even if you overheard it in passing, goosebumps will ripple your arms and saliva will line the roof of your mouth. It’s as natural as the rising of the sun, the changing of the seasons, or a last minute Manchester United goal. I’m getting carried away.

1980 saw Lancia initiate the 037 project in anticipation of the 1982 World Rally Championship, but more specifically the newly-formed Group B category that allowed manufacturers to enter vehicles with very few homologation requirements. A production run of 200 vehicles was all that was required, far fewer than previously (Group 4, i.e. Lancia Stratos, Fiat 131 Abarth, Ford RS1800 required a minimum of 400). And boy did it change racing.

The era, which we’ll cover in a separate CLT Editorial later in the year, allowed some of the fastest and most dangerous race cars every built to be raced in rally stages across the world, including the Audi Quattro S1, the Peugeot 205 Turbo 16 E2, and the Lancia Rally 037.

In the 1982 season, Lancia offered little, but when 1983 saw ’82’s champion, Walter Röhrl, join the team, it was a match made in heaven. The 037 powered to the Manufacturer’s title, and though Röhrl was still in with a shot of the Driver’s Championship heading into the final rally of the year, Great Britain, Lancia entered not one vehicle; and the Driver’s Championship went to Hannu Mikkola of Audi.

It was an incredible accomplishment for Lancia, considering that Audi, since the debut of their Quattro four wheel drive system in 1980, had set a template for future rallying success that the 037 ignored, being rear-wheel drive. In fact, although the Group B homologation category only lasted until 1986, every other rally championship winner since has used four-wheel or all-wheel drive.

The Lancia 037 Stradale, which carried the internal project code name because, presumably, they couldn’t think of anything better, was the road-going twin brother of the insane, Group B rally car.

It was a longitudinally-mounted, mid-engine, real wheel driven, untameable beast, or at least to mere mortals. The 2.0l four-cylinder unit was supercharged and produced 205hp, allowing 0-62mph in 5.8 seconds and a top speed of 137mph. Through two wheels. In a car that weighed 2,579 lb (1,170kg). The rally car weighed around 400lb (200kg) less…!

Of course, only 200 were made, or 207 in total, and they are seriously collectible for obvious reasons.

Back on the various surfaces of the WRC, Lancia, and the 037, weren’t able to replicate their ’83 success and were defeated by Audi, whilst 1985 also brought defeat, this time at the hands of Peugeot. RWD was no longer cutting it; something had to change. Fortunately, Lancia had a plan.

Delta Blow

Lancia had entered the S4 in 1985 alongside its RWD cousin, the 037, but it was in 1986 when it made the headlines; for all the wrong reasons.

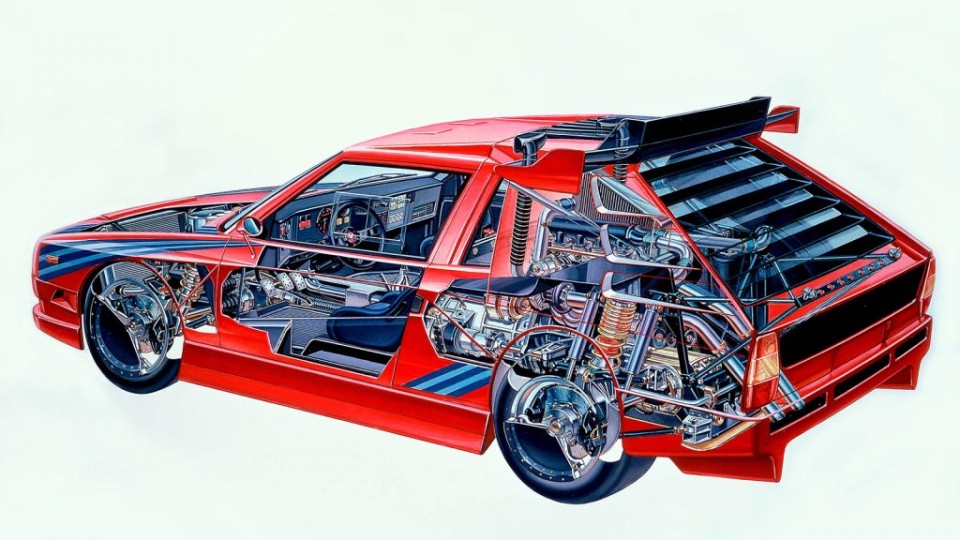

Due to categorisation of the Group B system, which was divided into engine sizes, the Delta S4 was in the under 2,500cc class with it’s 1.8l four-pot engine; though it produced 483hp (490PS) and some claim more still was possible. And that was in a car weighing 1962lb (890kg). Oh. My. Word.

In reality, the Delta S4 was a similar to its road-going namesake as I am to Dominic Purcell (yeah, I didn’t know who he was either but he was in Prison Break apparently). The doors were Kevlar composite, the body panels carbon-fibre composite and the structure itself was a tubular space frame.

But it did have to comply with Group B regulations, which meant 200 road-going siblings were required. And that’s how Lancia came to bless us with one of the coolest things that mankind has ever created. The Lancia Delta S4 Stradale.

Just look at it. It’s what you’ d expect if Zeus and Medusa got together and… you know… designed a car. The Stradale, which translated from Italian means road, was exactly that, the barely legal road-going equivalent of the Delta S4

Whilst it’s not clear how many were built, available information points to much less than the required 200, anyone jammy enough to own one was sure to appreciate the suede-covered steering wheel and air conditioning in addition to the 247hp (250PS) on tap, the 140mph (225km/h) top speed and 0-62mph (100km/h) acceleration in just 6.0 seconds.

It came with fibre-glass composite body panels, the same tubular construction as it’s rally-oriented sibling and the same longitudinally mid-mounted 1.8l four cylinder engine complete with supercharger AND turbocharger.

All of this should have been a crowning glory for Lancia, and rallying as a whole, when you consider the quite insane vehicles produced during this time frame. The Delta S4 Stradale was joined by the 205 Turbo 16, the Audi Sport Quattro S1, the MG Metro 6R4 Clubman (410bhp!), the Ford RS200 and, of course, the Renault R5 Turbo. But what happened in 1986 changed things forever.

Tragedy

The World Rally Championship of 1986 will go down, quite possibly, as the greatest championship in Motor Racing history. And I can promise you, this isn’t clickbait. Let me explain.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then the one above probably covers everything I’m about to say; and it’s missing both the Porsche 911CS RS and the Volkswagen GTi. But needless to say, after three years of Group B homologation, manufacturers were were now fully up-to-speed and knew what it took to win.

Engines were growing in power, shrinking in size and gaining superchargers and turbochargers. Body panels were getting considerably lighter thanks to clever composite panels, whilst every vehicle was now equipped with four-wheel drive. Everything was in place for a championship like never before. And that’s exactly what they got. But not in the way they’d hoped.

Corsica, Friday 2nd May, 1986. It’s the second day of the Tour of Corsica (Tour de Corse) and Henri Toivonen, in his Lancia Delta S4, has been in fine form. He was comfortably in the lead at the end of stage one, despite suffering from the flu and a persistent sore throat. Quitting was not an option.

Lancia had withdrawn from the last three rallies for varying reasons, and the Championship had already been tainted by the tragic deaths of three spectators in Portugal, where more than thirty people were also injured. But it was nothing compared with what was in stall for Toivonen.

The Finn had complained several times about the mental challenges of racing such a volatile car amongst the narrow, twisty mountain roads of Corsica. But it’s his final words on camera, prior to the eighteenth stage of the rally, that seem hauntingly prescient.

“Today, we have driven more than the whole distance of the 1000 Lakes Rally (Finnish Rally). After 4 hours of driving – it’s hard to keep up with the speed. So, with a modern car like this, it’s just impossible to race here. It’s physically exhausting and the brains can’t keep up with it anymore.”

Seven kilometres into the stage, as the road veered left and wound along a hillside, with a sheer drop off to the right, Toivonen seemed to miss the corner completely, driving straight off-the road and down the ravine, landing on its roof.

The aluminium fuel tank, which was positioned under the driver’s seat, had been ruptured by a tree branch and burst, almost immediately, into flames. The driver, and co-driver, who were trapped within the car as flames quickly engulfed it, were burned to death.

The car was unrecognisable afterwards, due to the Kevlar composite panels that covered the vehicle being highly flammable; the fuel tank was not covered by a skid-plate, as the course was tarmac.

Group B was cancelled almost immediately for the following season, as was the planned Group S, and though some manufacturers pulled out completely, other’s finished the season. But it was clear, upon reflection, that things had gone way, way too far. And it had taken such tragedies as the incidents in Portugal and Corsica for people to realise.

Experimental

Another affect of the tragic deaths of those involved in the 1986 season was that many manufacturers were left with cars that were either almost-complete or fully ready for competition; and nowhere to race them. Lancia were no different

The Lancia ECV (Experimental Composite Vehicle) was a prototype race car that the Italian marque had developed for the upcoming 1988 World Rally Championship, designed specifically to comply with the new Group S regulations; which were subsequently cancelled.

It combined a 600hp twin-turbocharged engine with a curious manifold arrangement, extensive use of composite materials and a unique red livery. It was, in some ways, a last hurrah of an era that had reminded us all of the tragic possibilities of racing, something that had been conveniently forgotten since Formula One introduced safety regulations in the ’50s & ’60s.

So, back to the relative safety of the road.

Evoluzione

The Turin Motor Show of 1986 saw the debut of the Lancia Delta HF 4WD, which would go on to be the back bone of every Lancia rally success of the next six years.

Whilst most of the technology remained the same, four-wheel-drive aside, the engine was changed to a 2.0l, twin-cam, 8-valve turbocharged engine derived from the Lancia Thema saloon, providing 163hp (165PS) in this guise.

Visually, it received integrated fog lamps that would soon be added as standard on all Delta derivatives, four separate front lamps that, again, would be adopted across the range, new bumpers and a twin-exit exhaust, plus all the usual model specific badging.

1987 brought all new regulations to WRC, and rightly so, Group B and S having been abandoned. Group A was therefore the pinnacle category of the rallying calendar, and as luck would have it, Lancia had developed the perfect foundations for an entrant.

With a minimum of 5,000 productions cars required per annum to enter category A, and amongst a field of competitors that ranged from the RWD Ford Sierra RS Cosworth and FWD Renault 11 Turbo to the Audi 200 Quattro, the Delta absolutely thrived.

In 1987, Lancia won nine of the thirteen rallies, including all three podium places in the U.S, and clinched both the manufacturer’s title and the Driver’s Championship, Juha Kankunnen rewarded for his consistency.

Lancia repeated the feat in 1988, Mike Biasion the Driver’s champion this time round, but the excitement revolved around the beginning of a rather legendary car in the Lancia Delta lineage. The Integrale.

In many ways, the Integrale is nothing special, in that it was simply an advancement of what had gone before. But because the foundations were already so bloody good, the Integrale, and what followed, were exceptional.

The “8v” refers to the eight valve engine, which was based upon that in the HF 4WD variant, but came with new valves, an upgraded turbocharger, 182hp (185PS) and, due to larger wheels and upgraded suspension components, flared wheelarches and other cosmetic changes.

And it looks superb. In the way a great white shark looks as it swims past you; from a distance. It’s when it starts moving towards you that you s**t yourself.

The “8v” dominated the 1988 WRC in racing guise, after being introduced for the third rally, in Portugal, and the “16v” went on to dominate the 1989 and 1990 championships thanks to the turbocharged 2-litre 16v engine that produced 197hp (200PS) in road going form and propelled it from 0-62mph (100km/h) in just 5.7 seconds.

The Frankfurt Motor Show of 1991 saw the debut of the Lancia Delta HF Integrale Evoluzione which would dominate the 1992 WRC championship for the non-works Martini-Racing team, Lancia having retired from racing at the end of the ’91 championship; after five successive titles!

The Evoluzione was exactly what it says on the tin, an evolution of the Integrale “16v”, with the same engine tweaked to 207hp (210PS) and various other underbody and aesthetic changes.

The Evoluzione II, the final evolution if you will, brought extensive changes in 1993, including a power hike to 212hp (215PS). It was the last hurrah for a model that, in racing, won the World Rally Championship six times in a row; and on the road, won the hearts of anyone who laid eyes on it, never mind those lucky enough to be behind the wheel.

Whilst some cars are looked on nostalgically, with rose-tinted spectacles that ignore the vast array of faults, the Lancia Delta deserves a place in our hearts, not because it was the last hurrah of a slowly dying company, but because it was the last of a dying breed.

It was noisy, temperamental (lethal) and designed with a sole focus in mind, and yet it was that mindset that delivered resounding success in racing and a reputation that only continues to grow.

As is typical of Lancia, its practically impossible to find production data for the production volumes of the first generation Delta, though conservative estimates still assume more than one million were sold during its fifteen year lifetime. What is clear, however, is that it was comfortably Lancia’s most popular car ever made.

And yet, good examples of Lancia Delta Integrales, in various guises, are comfortably fetching $40,000 and upwards today. Evoluzione spec cars with low mileage are worth upwards of $60,000.

The market has spoken.

Bootcamp

Before we leave the Delta series completely, it’s worth mentioning a little known Lancia called the Prisma. Which was actually nothing more than a Delta in a saloon body.

If I’d have introduced it as a Giorgetto Giugiaro-designed Lancia Delta derivative, you’d have got your hopes up, only to have them dashed. So I didn’t. But that’s exactly what it is. And, though it’s not a stunner, not much was back then, I think it has a certain charm.

One thing, however, is clear; having been based mechanically on the first generation Lancia Delta, it was an instant success. Though it shared the understructure, wheelbase, drivetrains, door and windshield of it’s hatchback sibling, it was different enough in customers eyes; so much so, that by 1984, Lancia had already produced 100,000. And sold them, presumably.

June 1984 saw Lancia launch a Diesel version, the marque’s first modern, diesel-powered car, which was only 11kg more than the petrol engine, and overall, the vehicle was considered a well-rounded offering for the segment, against offerings from Audi, BMW and Mercedes-Benz. It lasted until 1989 and sold well, though I cannot find total volumes anywhere!

Either way, it set a difficult challenge for its successor.

Stagnation

The success of the Delta up to, and including, 1993 makes the rest of what I have to say rather anti-climactic. Sorry. I got so caught up in the Delta story, that I failed to mention the other models that “burst” (see: dribbled) onto the scene. Beginning in 1984, with the Thema.

The Lancia Thema was Lancia’s 5-Series competitor, its E-Class-beater its… for goodness sake, look at it. It was never going to beat anyone, was it?

What’s disappointing is that it came from the same platform as the handsome Alfa Romeo 164 and the Saab 9000, yet managed to offer nothing in comparison to either, even when ’86 brought a range-topping Ferrari-derived V8 to the mix. It came in saloon and station wagon form, and the V8-engined 8:32 did come with a deployable spoiler that is so popular these days. Other than that…

In total, production lasted ten years and just under 360,000 were sold, most of them saloons. Let’s move on.

Decline

The replacement for the Prisma arrived in 1989 and was called the Dedra, I assume because it looked dead rubbish; but don’t quote me on that.

What became abundantly clear is that Lancia, under Fiat ownership, were being steadily guided away from creating desirable, well-engineered, stand-out products towards mass-volume standardised cars aimed at specific segments. And the Dedra was arguably the definition of this.

The name doesn’t ooze excitement or vitality does it? And neither did its appearance. Though the end of the ’80s and certainly the ’90s produced many mundane car offerings, the Dedra had, quite possibly, the smallest wheels I’ve seen on a Marketing vehicle, plus a fuel filler flap that surely didn’t need to be that low. And that’s just the beginning.

Though it had a strong focus on safety, combining several passive and active systems as standard, and a drag coefficient of just 0.29, it was in a segment that Lancia had only recently returned to, and was up against the likes of the BMW E36, which was selling roughly 300k per year, and the Mercedes-Benz C-Class, which was selling a little over 250k per year.

In the first generation’s ten-year cycle, the Dedra sold 418,084.

In 1993, Lancia introduced the second generation of the irreplaceable Delta, but it was, of course, underwhelming.

A year later, in 1994, the Thema was replaced by the Kappa, its new flagship model. It shared its platform with the much more handsome Alfa Romeo 166, and though there was no doubting the engineering quality below the bland metallic surface, most notably the refined range of powertrains, it was just too bland to look at

Italy continued to be Lancia’s biggest market, where it is still, even today, supported by a large and loyal following, and in 1995, Lancia introduced the Ypsilon to the world, which still exists today; but only in Italy.

At this point, I would normally wind down, mock the discarded remnants of Lancia’s recent past and sign off with a “toodle-pip” and a “please subscribe below”, except that the Ypsilon is an interesting vehicle, in that it might just explain the reason for Lancia’s demise.

The looks are one thing, it’s disgusting I know, but then most base Lancias were. That’s not what Lancia has ever stood for. Lancia were famous for excellently built, often over-engineered cars that were the perfect foundation for expert designers. And what changed in the days, weeks, months and years was, perhaps, a decision to move away from these foundations.

The Lancia Ypsilon debuted in 1995, a year after the debut of the similarly-styled Alfa Romeo 145/146, which to me is still one of the most handsome hatchbacks ever produced. The Alfa was produced on the “Type Two” platform, giving it similar underpinnings as the Lancia Delta and future products including the Fiat Coupé and the Alfa Romeo GTV. Dynamic, premium vehicles.

And the Ypsilon? Well it shared its underbody, chassis and powertrain with the Fiat Punto. Lancia, the premium brand with a racing heritage as competitive as most and a long and ancient history of dynamic, innovative vehicles, was producing a car with the same underpinnings as the Fiat Punto.

The Ypsilon was followed in 1998 by the Lybra, the replacement for the Dedra. It was somehow even uglier than the car it replaced, but came packed with technology and trim levels, everything you’d expect in the compact executive market segment.

It lasted until 2005, but was never replaced.

In 2001, Lancia brought us the Thesis, and it needs several thousand words to explain what on earth they were thinking. Actually, that’s a little harsh. Despite a rather curious front end, its tail lights were distinctive, somewhat similar to the X351 Jaguar XJ, and its interior, fit and finish and equipment levels were all well received.

Lancia (therefore Fiat) had put a lot of effort, and money, into the Thesis, and it showed. Yet despite the rave press reviews, the smooth ride and the incredibly competitive price (it’s price was set roughly 15% cheaper than the competition from the big German three), it sold only 16,000 units before production was cut short in 2009. Lancia’s brand reputation was beyond repair.

All Good Things…

Since the Thesis, the Lancia name has been used on rebadged vehicles such as the Chrysler 300, named Lancia Thema in Europe between 2011 & 2014, and the Fiat Idea, rebadged and re-trimmed the Lancia Musa between 2004 & 2012. But at that point, it was like watching your 16-year old dog battle old age and illness. Tortuous, and inevitable.

There’s considerable mystery surrounding Lancia, particularly from passionate, brand-loyal followers who insist that the rust fiasco of the ’70s would not, on its own, have been enough to damage its reputation. In reality, that’s neither here nor there.

All we know is that Lancia, who were famous for providing outstanding vehicles, and the basis for some of the prettiest and coolest cars the industry has ever seen, was also susceptible to a touch of over-engineering.

BMW and Mercedes-Benz in particular, following their rise from economic ashes, showed that it was possible to produce excellent, well-engineered, desirable cars in a premium segment; but you had to be smart. And it’s clear to me that Fiat didn’t get their strategy right with Lancia.

However, just like with many other automotive brands, particularly a certain Swedish brand, the legacy lives on, as much in the smiles of the people that drive the cars as the articles like this one. And whether you like Lancia or not, it’s impossible not to agree that they’ve left one incredible legacy behind. Grazie x

***

Well I hope you’ve enjoyed reading Lancia – A History as much as I’ve enjoyed writing it. To ensure you don’t miss out on similar articles from CLT, subscribe below and you’ll never miss out! Thanks x

Leave a comment